This sample Competition in Sport Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Competition is a process that has important positive and negative consequences for athletes. Positive consequences can include increased confidence, motivation, and satisfaction, whereas negative consequences can include stress and burnout. The degree to which competition has positive or negative consequences depends on the competitive context (e.g., the importance placed on performance and uncertainty) and the personality (e.g., trait anxiety, self-esteem) and perception of the athlete involved. Positive coaching strategies and stress management techniques can be used to reduce or cope with competitive stress.

Outline

- Introduction

- Competition and the Competition Process

- A Model for Understanding Competition

- Positive and Negative Effects of Competition

- Competitive Stress in Sport

1. Introduction

1.1. Competitive Sport: A Worldwide Phenomenon

Competitive sport is a worldwide phenomenon of enormous popularity. Epitomized by the Olympic Games and World Cup soccer championships, millions of individuals watch these events with tremendous enthusiasm. Moreover, countless others participate in various levels of competitive sport every year.

Competitive sport is not without controversy. Some argue that it is an excellent training ground for psychological attributes such as leadership, confidence, and teamwork, whereas others suggest that it leads to excessive anxiety, immoral behavior, and aggression.

Because of the persuasiveness of competitive sport, better understanding competition and the competitive process has been an important task for those in applied psychology. Three decades of sport psychological research on competition have provided a solid understanding of the area.

1.2. Purposes

This research paper has three purposes. First, competition is defined and the competitive process is discussed. Second, the issue of whether sport competition has positive or negative effects on participants is examined. Finally, competitive stress, its sources, and its consequences are discussed.

2. Competition And The Competition Process

Based on the groundbreaking work of Deutsch in 1949, early definitions of competition focused on situations where rewards were distributed unequally based on the performance of participants. Although this definition did much to guide early research in the area, its shortcomings (e.g., the fact that individuals do not always define rewards in the same way and, hence, that a person might lose an event but define his or her personal improvement as rewarding) led to the development of other definitions.

Today, competition is defined as a social process that encompasses a sequence of stages rather than a single event. Martens did much to advance the scientific study of competition when, in 1975, he defined it as a process where ‘‘an individual’s performance is compared with some standard of excellence in the presence of at least one other person who is aware of the criterion for comparison.’’ This differs from the reward definition in that the person is the focal point of the competition process and can influence the relationship among the various stages of competition. Primary emphasis is also placed on the individual’s perception of the competitive context and on how personality factors influence one’s competitive experience.

Standards of excellence involved in the competition process can be self-referenced (e.g., set a personal best in a 100-meter swim competition) or other-referenced (e.g., beat a particular individual in the competition). Considerable attention in contemporary sport psychology focuses on the utility of making self-versus outcome-oriented comparisons. Self-referenced standards are often emphasized because they are more in an individual’s control, and have been found to be associated with long-term motivation and greater satisfaction, compared with other-referenced comparisons.

3. A Model For Understanding Competition

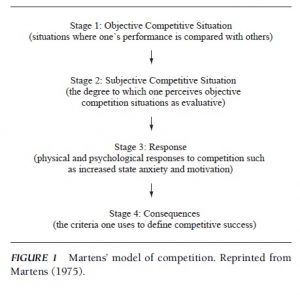

Guided by the process definition of competition, Martens also developed a four-stage model of competition (Fig. 1). An inspection of this model reveals that the objective competitive situation (Stage 1) begins the competitive process and consists of a situation where an individual’s performance is compared with others in the presence of least one other individual. For example, for most individuals, entering a gymnasium and seeing a basketball at midcourt and one’s name on the scoreboard would signal a competitive situation. However, not everyone would perceive this situation as competitive, for example, an elderly person who has no interest in or knowledge of basketball. Hence, Stage 2 of the process involves an individual’s subjective perception of the objective competitive situation. Research has shown that an individual’s personality orientations, particularly his or her levels of competitiveness or achievement goals (i.e., orientation to judge ability relative to oneself or a comparison with others), influence the degree to which the person sees situations as competitive.

After an individual appraises a situation as competitive, he or she may approach or avoid it or may become motivated, anxious, or excited. Thus, Stage 3 of the model focuses on an individual’s psychological– physiological response (e.g., anxiety, increased muscle tension, enhanced motivation). Interestingly, research also shows that it is not the absolute level of anxiety that influences an athlete’s performance; rather, it is whether the individual views that increased anxiety as facilitative and helpful or as debilitative and a hindrance to performance. The athlete’s perception, then, not only influences whether he or she views competition as anxiety provoking but also influences whether that anxiety is seen as helpful or hurtful.

FIGURE 1 Martens’ model of competition. Reprinted from Martens (1975).

FIGURE 1 Martens’ model of competition. Reprinted from Martens (1975).

Finally, the positive or negative consequences are the fourth stage in the competition process. An individual wins or loses on the scoreboard or perceives that he or she performed well or not. However, as with the three preceding stages, an athlete’s perception of the consequences is more important than the objective outcome. This model of competition is important because it shows that competition can best be understood as a series of stages. Moreover, it places an athlete at the center of the competitive process, with his or her personality dispositions interacting with environmental considerations.

4. Positive And Negative Effects Of Competition

The competitive ethic is a driving force in contemporary sport. It is common to hear coaches, athletes, and sports journalists say positive things such as ‘‘competition brings out the best in people’’ and ‘‘she is a fiery competitor.’’ At the same time, an overly competitive, win-at-all-costs mentality is blamed for violence, rules infractions, and unsportsmanlike behavior. Hence, sports competition appears to be a double-edged sword, cutting both ways and having both positive and negative effects on participants.

Most researchers do not view competition as inherently good or bad today. Research shows that it can have both positive and negative effects on participants. For instance, in some studies, competition has been shown to lead to negative effects such as increased aggression and decreased performance. In other investigations, competition has been found to facilitate motivation and lead to improved performance. Whether these effects are positive or negative depend greatly on the competitive context and the emphasis that sport leaders and coaches place on competition and its meaning. For example, the quality of adult leadership has been shown to be a crucial determinant of whether competition has positive or negative outcomes for children. In their classic youth sports coaching research, Smoll and Smith found that children playing for coaches trained in a positive approach (i.e., who focused on encouragement and giving praise) exhibited higher self-esteem and lower anxiety and were less likely to drop out of sport. When coaches were not trained to be positive and encouraging, children involved in competitive sport did not experience increased motivation, lower anxiety and enhanced self-esteem.

Much of the sport psychological research focusing on competition has been conducted with young athletes in entry-level programs. Less research on competition has been conducted at different levels of competition (local, national, and international). However, recent research with elite athletes shows that these outstanding performers are highly competitive. Their standards of comparison are both self and other-referenced, they are both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated, and they have high perceptions of ability.

Champion athletes have also been found to approach competition differently across various phases of their careers. For instance, in the classic research by Bloom in 1985, elite athlete development was retrospectively traced across the careers of champion athletes. Bloom’s research, as well as more recent research, found that these individuals did not begin their careers with an emphasis on competitive outcome (i.e., winning medals and defeating others). Rather, the focus was on having fun, learning fundamentals, and being active. It was only later that they approached competition in a very serious fashion. In addition, for much of their careers, they focused on long-term development rather than short-term competitive results.

5. Competitive Stress In Sport

One of the most studied aspects of competitive sport has been its association with competitive stress. Levels of stress experienced by young athletes, sources of stress, and managing stress all have been topics of considerable interest to sport psychology researchers.

5.1. Stress in Sport

Stress has been defined as an athlete’s perception of the imbalance between the environmental demands placed on him or her and the athlete’s response capacity and resources for meeting those demands. For example, a golfer may face a situation where he or she needs to sink a crucial 15-foot putt to win a tournament. If the golfer perceives the demands as exceeding his or her capabilities, the result is increased competitive state anxiety, that is, feelings of apprehension and tension accompanied by physiological activation. Furthermore, heightened levels of state anxiety, especially if they are perceived as debilitative, have been associated with poor performance and lower levels of enjoyment and satisfaction.

5.2. Sources of Stress in Athletes

Identifying sources of stress experienced by athletes engaging in competition has been a topic of interest to sport psychologists. This research has generally shown that although there are a variety of specific stress sources that an athlete can experience (e.g., self-doubts about performance capabilities, team selection), these fall into two general situational categories: (a) the importance placed on performance and (b) uncertainty. Specifically, the more importance that an athlete perceives is placed on an event, the more state anxiety is experienced. Similarly, the greater the degree of uncertainty (whether about performance or nonperformance issues) that the athlete perceives, the more competitive state anxiety is experienced. However, situational factors are not the only class

of factors influencing competitive stress responses. Consistent with Martens’ model of competition, personality dispositions have been associated with elevated stress responses. Specifically, an athlete’s level of trait anxiety (i.e., a personality orientation that predisposes the individual to view social evaluation and competitive contexts as threatening) influences his or her level of state anxiety. Performers with high trait anxiety consistently respond with greater levels of state anxiety in competitive situations. Self-esteem has also been consistently associated with levels of competitive state anxiety experienced in socially evaluative sport contexts. In competitive situations, athletes with low self-esteem experience higher levels of state anxiety than do those with high self-esteem. Finally, more recent studies have found relationships between increased anxiety and high levels of hardiness, perfectionism, and self-presentation concerns as well as low social support, although these findings need to be further verified in additional studies.

5.3. Are Young Athletes Placed under Too Much Stress?

For a number of years, researchers have been concerned with the levels of stress experienced by athletes, especially young athletes engaged in competitive sports. Thus, researchers have compared the amounts of state anxiety experienced during practices with those experienced during competitive sport situations. The thinking

behind these comparisons is that competition is more anxiety provoking than are practices, but it is important to note that at times practices can include considerable social evaluation (e.g., team selections). Although the results of these studies have consistently revealed that most young athletes experience more anxiety during competitions than during practices, the most important finding is that the vast majority of children do not experience excessive levels of state anxiety during competitions. However, certain children in certain situations do experience high levels of competitive stress and anxiety.

For example, in a set of classic studies of competitive youth sport participants, Scanlan and colleagues assessed the state anxiety levels of youth sport participants during practices (i.e., nonevaluative contexts) and compared these levels with those during competitions (i.e., evaluative contexts). A variety of personality and background factors were also assessed. Results of this research led to the general conclusion that most young athletes did not experience excessively high levels of state anxiety during competitions. Certain children in certain situations did experience high levels of state anxiety. These children were characterized by high competitive trait anxiety, low self-esteem, less fun, less satisfaction with performance, low personal performance expectancies, and worries about failure and adult evaluation.

In a related area of research, ‘‘burnout’’ or withdrawal from competitive sport has been studied. In these studies, burnout has been defined as a psychological, physiological, and/or emotional withdrawal from sport due to exhaustion, depersonalization, and low-accomplishment feelings resulting from chronic stress. Results reveal that a small percentage of sport participants experience burnout of sport and that chronic stress plays an important role in the burnout process. Moreover, the chronic stress results from physical overtraining and/or psychological factors such as overbearing parents or coaches, a lack of athlete multidimensional identity development, a perfectionistic personality orientation, high trait anxiety, and low self-esteem.

5.4. Managing Competitive Stress

Because competitive sport can be stressful, and high levels of stress have been associated with inferior performance and decreased enjoyment and satisfaction, researchers have been very interested in helping athletes to manage stress.

One important but often overlooked class of techniques for managing competitive stress is environmental engineering. With environmental engineering techniques, coaches, adult leaders, and significant others can influence athlete stress levels by increasing the importance placed on competition (e.g., giving a fiery pregame pep talk, repeatedly emphasizing the importance of victory) or by creating uncertainty (e.g., not announcing starting lineups for games, basing liking for a child on performance). Or, they can reduce competitive stress by reducing the importance placed on performance (e.g., not giving a pregame pep talk, not repeatedly emphasizing the importance of victory) or by increasing certainty (e.g., announcing starting lineups early, not basing liking for a child on performance). Training youth sport coaches to adopt a positive and encouraging coaching orientation, rather than a negative or critical one, can reduce the levels of competitive stress experienced.

A number of techniques, mirroring general stress management research in psychology, have been used successfully by athletes to manage their competitive stress. These include cognitive anxiety reduction strategies (e.g., imagery, meditation), somatic anxiety reduction techniques (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation, breath control, biofeedback), and multimodal techniques (e.g., stress inoculation, cognitive–affective stress management training). Competitive athletes have also been found to use a variety of problem-focused (e.g., time management, goal setting) or emotion-focused (e.g., controlled breathing, relaxation training) coping techniques to control the stress of competition.

Relative to the utility of teaching stress management to athletes, sport psychologists emphasize the need for long-term training/practice and the incorporation of these techniques into the actual competitive setting (e.g., learning how to relax while an athlete actually runs vs using relaxation techniques the night before a race). Finally, research has also revealed that there is an optimal recipe of emotions that lead to superior sport performance, so that using stress management techniques to eliminate all stress is counterproductive. Thus, competitive athletes must know their optimal levels of emotional arousal and arousal-related emotions needed for best performance and then use stress reduction and enhancement strategies accordingly.

Bibliography:

- Bloom, B. S. (Ed.). (1985). Developing talent in young people. New York: Ballantine.

- Deutsch, M. (1949). An experimental study of the effects of cooperation and competition upon group processes. Human Relations, 2, 199–231.

- Gill, D. (2000). Psychological dynamics of sport and exercise (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Gould, D. (1993). Intensive sport participation and the prepubescent athlete: Competitive stress and burnout. In B. R. Cahill, & A. J. Pearl (Eds.), Intensive sport participation in children’s sports (pp. 19–38). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Hanin, Y. L. (Ed.). (2000). Emotions in sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Horn, T. (2002). Advances in sport psychology (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Jones, G., Hanton, S., & Swain, A. (1994). Intensity and interpretation of anxiety symptoms in elite and non-elite sports performers. Personality and Individual Differences, 17, 657–663.

- Martens, R. (1975). Social psychology of sport. New York: Harper & Row.

- Scanlan, T. K. (1986). Competitive stress in children. In M. R. Weiss, & D. Gould (Eds.), Sport for children and youth (pp. 113–118). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Smith, R. E., Smoll, F. L., & Curtis, B. (1979). Coach effectiveness training: A cognitive–behavioral approach to enhancing relationship skills in youth sport coaches. Journal of Sport Psychology, 1, 59–75.

- Smoll, F. L., & Smith, R. E. (Eds.). (2002). Children and youth in sport (2nd ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

- Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2003). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.