This sample Economics of Migration Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Like other free research paper examples, it is not a custom research paper. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our custom writing services and buy a paper on any of the economics research paper topics.

The economics of migration is a sizable topic area within economics that encompasses broadly defined studies of the movement of people within and across economies. Studies of intranational, or internal, migration focus on movements within a country’s borders, whereas studies of international migration (emigration and immigration) focus on movements across international boundaries. The economics of migration spans several subdisciplines within economics. Both microeconomists and macroeconomists are interested in how migration affects markets for labor, other factors of production, and output. Labor economists are particularly interested in migration as it is an important determinant of labor market outcomes such as wages and employment. Public economists and public policy makers are interested in the effects of migration on the social surplus and in the interrelationships between migration and public policy instruments. Economists studying economic development and international economics are interested in how migrations affect economic outcomes in the developing world and in the global economy broadly.

This research paper outlines the key theoretical elements of micro-economic and macroeconomic models of migration and presents empirical evidence from representative applied studies of intranational and international migration to date. Special attention is given to the debate about immigration into the United States and its consequences for both natives and immigrants.

Microeconomic Theory

Economic Benefits and Costs

In his classic article, “A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures,” Charles Tiebout (1956) hypothesized that people “vote with their feet” by migrating to localities with public expenditure characteristics that best fit their personal preferences. Tiebout’s model illustrates, for example, how residential decisions are related to taxation and expenditure characteristics such as local tax rates and the quality and quantity of publicly provided goods such as education and local amenities.

In microeconomic models of migration, “voting with one’s feet” is generally modeled by assuming that individuals make decisions regarding remaining at a current location versus moving to a preferable location. In its simplest form, the model may be described by agents maximizing net present value of lifetime earnings and engaging in migration if the difference in lifetime earnings between a potential destination and the agent’s origin is positive and greater than migration costs. Thus, agents make investments in their human capital by moving to where their economic opportunities, as measured by lifetime earnings net of migration costs, are improved (Sjaastad, 1962).

Agents in these migration models are assumed to maximize their welfare by comparing net economic benefits (benefits minus costs) at an origin and at alternative locations in a large set of potential destinations. The decision therefore is not only whether to migrate but also where to migrate if a migration is to be undertaken. Economic benefits and costs are not the same thing as financial or accounting benefits and costs. Instead, economists use surplus areas (e.g., consumer and producer surplus) to define these concepts. In addition to accounting costs, opportunity costs are included to form the cost definition, and welfare is measured relative to some status quo.

In extensions to the basic model, agents take into account factors that influence economic and psychic benefits and costs such as labor market variations, public policy and environmental attributes of various locations, and personal characteristics and circumstance. Furthermore, expected benefits and costs may differ depending on whether an individual will be migrating with or without family, legally or illegally, and so on. To complicate this further, precise values of economic benefits and costs often are unknown, and thus agents are thought to make decisions based on expected net benefits, instead of deterministic ones. Expected values take into account probabilities of uncertain outcomes.

If agents are assumed to be utility maximizers, then agents maximize expected utility by choosing to migrate to a destination from their set of potential destinations (which includes a stay at origin option) that maximizes expected net benefits where expected incomes and costs are mapped into utility terms. Expected net benefit to a person from making a migration is the difference between that agent’s expected utility at the destination and his or her expected utility at the origin plus expected migration costs.

On the benefit side, expected income/utility may include both expected wage earnings and expected supplementary nonwage income such as public aid payments. More broadly, economists may include value of factors such as participation in public schooling and environmental amenities. Since both wage and nonwage income are expected measures, the probability of employment (and likewise the probability of receiving aid) should be included in the calculation. Agents compare these expected benefit values for each potential destination to expected utility at the origin, where again this may depend on probabilities of employment and of nonwage income as well as differences in generosities.

On the cost side, expected costs may be thought to be a function of monetary, opportunity, and psychological costs. An agent’s total expected monetary cost of migration includes direct travel expenses. Opportunity costs of migrating to the United States include any foregone income at the origin and account for travel time and distance. Expected psychological costs associated with migration may include elements such as leaving family or one’s homeland and may depend on travel distance and time. If a migrant intends to return to the sending location, then expected costs should represent round-trip costs. In the case of illegal migration, expected costs may include probabilities of apprehension and deportation and related costs (e.g., court costs, opportunity costs of time, and additional psychological costs) and any monetary payments to agents such as border smugglers for assistance in the trip.

All values on both benefit and cost sides may depend on a particular time of migration given varying political and economic contexts. Several locational attributes should also influence the propensity to choose one destination over another. High unemployment rates and other negative indicators of labor market conditions, for example, should be associated with decreases in the probabilities of employment at the destination and origin. Increases in average wages of similar workers and potential values received from social service programs, hospitals, and educational systems should be positively related to expected incomes. For those migrating illegally, border patrol intensity and the political economy of immigration policy may affect benefits and costs of migration. Furthermore, personal and professional networks may increase the probability that one crosses successfully and of employment at a destination. Networks also may increase the probability of receiving public aid benefits if experienced friends and family members help in the application process and may decrease both the monetary and unobserved psychological costs of crossing.

These considerations can shed light on applied questions such as the determinants of illegal immigration from Mexico into the United States. While the magnitude of illegal immigration cannot be known with certainty, it has clearly increased significantly over the past 30 years. By some estimates, the inflow of illegal immigrants has increased by a factor of five since the 1980s.

What can explain this long-term trend of increasing illegal immigration? Large wage differentials encourage illegal immigration (given limits on legal immigration) while enforcement of immigration law discourages it. These factors alone, however, cannot explain its long-term rise. One explanation is that migration is encouraged by the spread of social networks. When migrants from Mexico arrive in the United States, they are able to find friends and family from Mexico who welcome them, help them find jobs and housing, and otherwise facilitate their adaptation to the United States. Illegal immigration is thereby self-sustaining. It tends to grow over time because it spreads and deepens the social networks that facilitate it. (It is also worth noting that this growth of illegal immigration explains the increasing intensity of the controversy over it, a point we return to below.)

Macroeconomic Theory

Gravity Models

Gravity models, used in migration and trade flow literature, are used by economists to assess and predict aggregate migrant flows between pairs of locations. This is in contrast to the individual migrant decision-making models above. Gravity models borrow techniques from physics, and the applicability of a gravity model of migration depends on the relevance of the assumption that migrations of people follow laws similar to gravitational pulls. In gravity models, migration is assumed to move inversely with distance and positively with the size of an economy (squared), often measured by population size.

Modified gravity models characterize the recent literature following this technique. For example, Karemera, Oguledo, and Davis (2000) add sending and receiving country immigration regulations to the traditional gravity framework, and Lewer and Van den Berg (2008) include a measure of relative destination and sending country per capita income and show how the effects of supplementary variables on immigration to the traditional gravity model can be estimated in an augmented framework.

Applications and Empirical Evidence

Econometric discrete choice modeling, a type of multiple regression, is a common technique used by economists to quantify determinants of migration for various populations of study, and econometric selection models have been used to study the effects of migration on economic outcomes. Some of these applications will be discussed here.

Intranational Migration

Literature on the determinants of intranational migration suggests that life cycle considerations (e.g., age, education, family structure) and distance are key predictors of internal migrant flows (Greenwood, 1997). A complication to the unitary model of migration is that family units often migrate together, and therefore migration decision making may occur at the family level as opposed to the individual. Specifically, families may maximize family welfare as opposed to individual welfare with some family members suffering losses as the result of migration and others realizing offsetting gains.

In addition, locational attributes and amenities (disamenities), both environmental and those that are the result of public policy and market conditions, have been shown to attract (repel) internal migrants. Significant effort in economics literature has been made to examine the possibility of welfare migration or migration in response to differences in public aid availability and generosity across locations. McKinnish (2005, 2007), for example, in her examination of internal migration between U.S. counties, finds that having a county neighbor with lower welfare benefits increases welfare expenditures in border counties relative to interior counties. Welfare migration may occur among both those native to a country and new to it.

International Migration

The Immigration Debate in the United States

Intranational migration is rarely controversial. In contrast, international migration often arouses heated controversies and inflammatory rhetoric. That may seem odd in the context of the United States since we like to think of ourselves as a “nation of immigrants.” Why are there such passionate arguments about people who seem to like our country so much that they want to move here?

It is worth taking a moment to address this question since it puts the more technical issues in a larger, interpretive framework. The most direct answer concerns the sheer number of people who come to the United States each year. Since 2000, an average of about one million legal immigrants (Department of Homeland Security, 2008) and about 700,000 illegal immigrants (Passel & Cohn, 2008a) have entered the United States each year. About 300,000 foreigners have left the United States each year (Shrestha, 2006). Thus, net immigration has been directly increasing the U.S. population by 1.4 million persons per year. Net immigration then has indirect, subsequent effects on population growth due to immigrant fertility.

Taken together, the direct and indirect impacts of immigration on the U.S. population are startling. The Census Bureau projects that the total U.S. population will grow to 439 million by 2050, an increase of 157 million, or 56%, since 2000. To put this in concrete terms, this is equivalent to adding the entire populations of Mexico and Canada to today’s (2009) population of the United States. According to Passel and Cohn (2008b), over four fifths of that growth will be due to immigrants and their descendents. Thus, immigration is dramatically increasing the number of people living in the United States.

Rapid population growth puts stress on society, on the environment, on the economy, on schools and neighborhoods, and on government. More people means more pollution, more crime, more crowding, and more need for government services. Americans take pride in their immigrant history, but they are also concerned about the impact of large-scale immigration, particularly when much of it seems to be illegal and uncontrollable. They are empathetic with immigrants, but they also are concerned about their own citizens and their own national identity. That conflict explains the intensity of the debate about U.S. immigration policy. Americans are caught between competing ideals, and neither side of the debate is obviously right.

Of all the concerns raised by mass immigration, its economic impact is perhaps the most complicated. Immigration has both good and bad effects on the economy and the workers of the host country that can be difficult to separate out. On one hand, immigration adds to labor resources and thus to the capacity for economic growth. Growth increases national income and potentially raises living standards. Immigrants “take jobs that Americans do not want” (as it is commonly said) and produce goods and services that otherwise would not be produced; that generates income for Americans as well as for immigrants. The capacity for immigration to increase the incomes of natives will be especially strong for the employers who hire the immigrants and for the more highly educated native workers whose skills complement the immigrants (in effect, the two groups establish a division of labor that benefits both). This is one basis for the claim that immigration is beneficial for the host country.

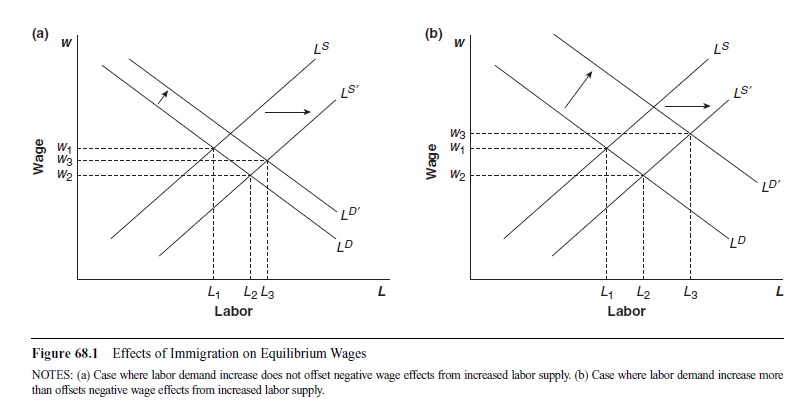

On the other hand, large-scale immigration can also harm native workers. It is a classic labor supply shock: It increases the competition for jobs and thus drives down employment and wages for native workers, especially those whose skills are most similar to those of the immigrants. Figure 68.1 illustrates a labor supply shock corresponding to large-scale immigration. In response to the shock on the labor supply side only, equilibrium labor increases from L1 to L2 while wages decrease from w1 to w2. Immigration, however, may have unpredictable effects on wages if labor demand also changes. Panel (a) of Figure 68.1 illustrates where a demand increase less than offsets the negative wage effect from increased labor supply. The final wage, w3, is lower than the initial equilibrium wage, w1, despite the demand increase. Panel (b) shows that the same model under different conditions, however, may yield the opposite.

Because immigrants (especially illegal immigrants) to the United States are likely to have low levels of education— one third of foreign-born persons in the United States and almost two thirds of persons born in Mexico lack a high school degree (Pew Hispanic Center, 2009)—they compete most directly with native workers who have not attended college and especially with those who have not completed high school. These native workers are likely to earn low wages and to be on the bottom of the income distribution. African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and immigrants are especially likely to fall into this category. Thus, immigration tends to be most harmful for low-wage native workers and ethnic minorities.

Of course, immigration can simultaneously increase both job competition and economic growth. Because the former tends to harm low-income natives and the latter tends to help high-income natives, the result is an increase in inequality. In other words, immigration can have regressive effects on the income distribution of natives. The economy may grow, but the benefits of that growth flow away from the bottom and toward the top.

Because the rise in income for some natives is offset by the decline for others, the aggregate effects can wash out. These countervailing tendencies are typical of immigration. Consider the impact on productivity: Immigration can increase productivity growth if it stimulates economic activity and investment, but it can reduce productivity if the surplus of low-wage workers discourages the substitution of capital for labor. Or consider the impact on government budgets: Immigrants decrease budget deficits because they pay taxes, but they increase budget deficits because they use services. Because immigration can have contradictory effects that can cancel each other out, it may be more revealing to focus on its impact on specific groups of natives rather than on the United States as a whole.

Immigration and Job Competition

Perhaps the key issue at stake in the debate about immigration is the degree of job competition. The claim that immigrants “take jobs that Americans do not want” reflects a misunderstanding of microeconomics. The extent to which Americans want jobs (the labor-leisure trade-off) is a function of their pay. If labor supply shocks created by immigration drive down the wages in these jobs so that native workers leave them, it does not follow that Americans do not want these jobs. In the absence of immigration, wages would rise and American workers would be drawn back into them.

Figure 68.1 Effects of Immigration on Equilibrium Wages

Figure 68.1 Effects of Immigration on Equilibrium Wages

One way of examining this issue is to compare the occupational distribution of immigrants to natives. The two show significant overlap. According to the Pew Hispanic Center (2009), fewer than 1 in 20 foreign-born Hispanics are in agricultural or related occupations. While illegal Hispanic workers are likely undercounted in these estimates, this still suggests that the common perception that most Hispanic immigrants work in the fields—the classic “jobs that Americans do not want”—is mistaken. Most Hispanic immigrants work in occupations that native workers also hold. For example, approximately 1 in 3 foreign-born Hispanics are in construction and maintenance occupations. Their occupational distribution is more skewed toward low-wage work than non-Hispanics, but there is still considerable occupational overlap, particularly with respect to low-wage jobs. This is not consistent with the notion that immigrants and natives are in separate labor markets (a difficult notion to reconcile with the high degree of mobility and fluidity in the U.S. labor market).

To the extent that the skills and occupations of immigrant and Hispanic workers overlap, the employment and wages of native workers will be depressed by competition with immigrant workers. That is the finding of a number of researchers, most notably George Borjas (2003, 2006) and Borjas and Katz (2007). These authors find that a 10% increase in the labor supply created by immigration (about equal to the increase from 1980 to 2000) depresses the wages of all native workers by about 3% and depresses the wages of native workers without a high school degree by about 8%. These percentages are economically significant, and Borjas (2003) concludes that “immigration has substantially worsened the labor market opportunities faced by many native workers” (p. 1370).

Borjas (2003) describes his results as consistent with the simple textbook model of wage determination. However, other researchers have concluded that immigration has virtually no impact on the wages of native workers. David Card (2005) shows that the wages of native high school dropouts have not declined relative to the wages of native high school graduates since 1980, as one would expect if immigration had had the most negative impact on the wages of the least educated American workers. He concludes that “the evidence that immigrants harm native opportunities is slight” (p. F300).

Card’s (2005) evidence is indirect. Instead of looking at the impact of immigration on the wages of native workers without a high school degree, he looks at their wages relative to the wages of native workers with a high school degree. The finding that their relative wages have not declined is surprising given that nationally, the real hourly wage of male and female high school dropouts fell from 1990 to 2005 while it rose for all other educational groups (Mishel, Bernstein, & Shierholz, 2009).

Card (2005) speculates that native workers are not displaced by immigrants because firms grow and invest in labor-intensive technologies in response to the availability of immigrant workers. Firms may be more likely to move to cities with large immigrant populations that make it easy to hire low-wage workers. As a result, labor demand can increase and offset the immigrant-induced increase in labor supply. Panel (b) of Figure 68.1 illustrates this case. In the figure, a demand increase more than offsets the negative wage effect from increased labor supply. The final wage, w3, is higher than the initial equilibrium wage, w1. Of course, depending on the magnitude of the demand shift, cases in which wages remain below w1 (but are greater than w2) also are possible.

This argument illustrates the capacity of the economic system to mitigate the impact of shocks over time. Immigration drives down wages over the short run by boosting labor supply, but that effect dissipates over the long run due to offsetting increases in labor demand. Other long-run adjustments demonstrate the same tendency. For example, native workers who face increasing job competition from immigrants may respond by moving to places where there are fewer immigrants. That will reduce labor supply and thus the measured impact of immigration on wages in the cities that the native workers have left (by 40% to 60% according to Borjas, 2006). Also, the native workers most marginally connected to the labor force may drop out of the labor force in response to competition from immigrants (Johannsson, Weiler, & Shulman, 2003). That takes the lowest wage native workers out of the sample, thereby raising the average wage of the workers who remain (this is similar to the argument made by Butler & Heckman [1977] about the impact of welfare on average black labor force participation and wages).

It is important to note that the capacity of the economic system to adjust to shocks over the long run does not negate the losses that have occurred and accumulated over a succession of short-run states. The short-run losses continue to occur as immigrant inflows continue. These inflows tend to rise and fall with the state of the economy and the degree of enforcement of immigration law; nonetheless, they are projected to continue in large part indefinitely. If that projection proves to be true, the “short-run” losses from immigration-induced labor supply shocks will never cease even if each shock tends to diminish over time. In this sense, both Card and Borjas can be right.

Immigration, Growth, and Inequality

In the United States, immigration lowers the wages and employment of low-wage workers, but it also increases economic growth and national income. The recipients of this additional income—aside from the immigrants themselves—are the employers of the immigrants and the workers whose skills are complementary to the immigrants or who provide services to the immigrants. Since these tend to be high-skill, high-wage workers and since large employers typically have high incomes, it follows that many beneficiaries of immigration to the United States are relatively affluent.

Much of the above analysis refers to the immigration of low-skill workers. Of course, many other immigrants are highly skilled. Immigrants are almost as likely as natives to hold a bachelor’s degree and are somewhat more likely to hold a graduate degree (Pew Hispanic Center, 2009). Highly skilled immigrants bring technical and entrepreneurial skills into the United States that add to productivity, innovation, and growth. One study shows that a 1% increase in the share of immigrant college graduates in the population raises patents, relative to population, by 6% (Hunt & Gauthier-Loiselle, 2008). However, high-skill immigrants can create job competition for high-skill natives, just as low-skill immigrants can create job competition for low-skill natives. Borjas (2005) estimates that a 10% immigration-induced increase in the supply of doctorates lowers the wages of comparable natives by 3%.

Immigration also affects prices, and that also should be factored into the discussion of its overall economic consequences. Although the low wages earned by the majority of immigrants can harm the workers who compete with them, this lowers the prices of the goods and services they produce. This unambiguously benefits native consumers. Cortes (2008), for example, finds that a 10% increase in the share of low-skilled immigrants in the labor force decreases the price of immigrant-intensive services (e.g., housekeeping and gardening), primarily demanded by high-income natives, by 2%. This is suggestive of surplus gains resulting from depressed prices as an additional result of immigration.

Immigration thus has a variety of both positive and negative effects on U.S. natives. Since the negative effects tend to be concentrated among low-income natives, and since the positive effects may be concentrated among high-income natives, there are two overall consequences. First, immigration may increase inequality along with other trends such as technological change, the decline in unions, international competition, and deindustrialization. The extent (and existence) of that increase in inequality is a matter of dispute, as one would expect from the corresponding dispute about the impact of immigration on the wages of low-skill native workers. Borjas, Freeman, and Katz (1997) conclude in a widely cited paper that immigration accounts for a quarter to a half of the decline in the relative wages of low-skill native workers. That would make it a significant factor in the increase in inequality between low-wage and high-wage workers. In contrast, a more recent paper by Card (2009) concludes that immigration does not significantly increase wage inequality.

Second, the gains and losses from immigration may approximately cancel out in the aggregate. This can be understood in two ways. First, the gains that accrue to affluent Americans are offset by the losses to low-income Americans; second, the benefits created by high-skill immigrants are offset by the losses created by low-skill immigrants. Consequently, the estimates of the aggregate impact of immigration are small relative to the size of the U.S. economy. The study of immigration conducted by the National Research Council (1997) concluded that immigration adds at most about 0.1% to gross domestic product (GDP).

Even that small benefit gets wiped out by the net fiscal costs imposed by immigration. Immigrants are disproportionately likely to have low incomes and large families. Thus, they have relatively high needs for social services (particularly schools) but pay relatively little in taxes. The fiscal balance is positive at the federal level because the federal government receives the Social Security taxes of immigrants but provides little in the way of services or Social Security benefits; however, it is negative at the state and local levels, substantially so in the locales most heavily affected by immigration. The negative effect outweighs the positive effect by a small amount. The study just cited showed that the current fiscal burden imposed by immigration is only about $20 per household as of the mid-1990s, but added up over all households, it amounts to an overall loss of about the same amount as immigration adds to economic growth. It therefore seems safe to conclude that the overall economic effect of immigration is approximately zero. In this sense, both sides of the immigration debate (one claiming that immigration is an economic disaster and the other claiming that immigration is an economic necessity) are wrong.

These conflicting considerations do not lend themselves to simple conclusions about the impact of immigration. Overall judgments will depend upon which group we view with most concern. For example, immigrants clearly benefit from immigration, so those who care most about the well-being of immigrants will support a more expansionist approach to immigration. Those who care most about low-income natives would support a more restrictionist approach. Those who care most about the business sector would support a more expansionist approach. Other policy combinations could arise as well. For example, those who care about both immigrants and low-income natives might support a more expansionist approach combined with government assistance to the adversely affected natives. Or those who care most about both immigrants and low-income natives might support a more restrictionist approach combined with government foreign aid to raise standards of living and reduce the incentive to emigrate from sending countries. These complicated ethical and political judgments cannot be resolved just by recourse to the economic evidence.

Immigrant Assimilation

In addition to the economic effects on U.S.-born workers, another area of debate concerns economic assimilation or whether immigrants’ earnings distributions approach those of natives as time elapses within a host country. Recent empirical evidence generally does not support full economic assimilation by immigrants. Cross-sectional regressions in the early literature predicted rapid increases in immigrant earnings upon arrival in the United States. Borjas (1985), however, found that within-cohort growth is significantly smaller than previous estimates using cross-sectional techniques. In a follow-up, Borjas (1995) found evidence that increases in relative wages of immigrants after arrival in the United States are not enough to result in wages equivalent to those of like natives. Instead, immigrants earn 15% to 20% less than natives throughout most of their working lives.

There also are mixed results regarding assimilation across generations. Some authors argue that intergenerational assimilation may be faster than assimilation of migrants themselves. Card (2005), for example, argues that while immigrants themselves may not economically assimilate completely, children of immigrants will join a common earnings path with the children of natives, and thus assimilation is an intergenerational process. Therefore, intergenerational assimilation may be faster than assimilation of immigrants themselves. Smith (2003) finds that each successive generation of Hispanic men has been able to decrease the schooling gap, and this has translated into increased incomes for subsequent generations. On the other hand, some authors have argued that Mexican immigrants have slower rates of assimilation in comparison to other immigrants. Lazear (2007), for example, argues that immigrants from Mexico have performed worse and become assimilated more slowly than immigrants from other countries. He argues that this is the result of U.S. immigration policy, the large numbers of Mexican immigrants relative to other groups, and the presence of ethnic enclaves.

Immigrant Locational Choice

A number of state economic and demographic conditions and state policy instruments can be hypothesized to affect the locational distribution of immigrants. Bartel (1989) studies the locational choices of post-1964 U.S. immigrants at the city level and finds that immigrants are more geographically concentrated than natives while controlling for age and ethnicity and that education reduces the probability of geographic clustering and increases the probability of changing locations after arrival in the United States. Jaeger (2000) finds that immigrants’ responsiveness to labor market and demographic conditions differs across official U.S. immigrant admission categories, including admission based on presence of U.S. relatives, refugee or asylee status, and employment or skills. Employment category immigrants, for example, are more likely to locate in areas with low unemployment rates. Other determinants of locational choice are wage levels and ethnic concentrations. A growing literature has examined how information networks affect migration decisions and outcomes conditional on arrival. Munshi (2003), for example, finds that Mexican immigrants with larger networks are more likely to be employed and to hold a higher paying nonagricultural job.

As in studies of internal migration, the possibility of welfare migration has been another theme in economic literature on the effects of international migration. If immigrants choose locations based on welfare availability and generosity, there may be fiscal consequences to certain communities. Like the literature on the effects of immigration overall, the literature on immigrant welfare migration is characterized by debates over appropriate data sources, econometric methods, and ultimate results.

Borjas (1999) presents a model of whether welfare-generous states induce those immigrants at the margin (who may have stayed home or located elsewhere in the absence of welfare) to make locational decisions based on social safety net availability. He examines whether the interstate dispersion of public service benefits influences the locational distribution of legal immigrants relative to the distribution of U.S.-born citizens. In this framework, he demonstrates that immigrant program participation rates are more sensitive to benefit-level changes than native participation rates are. Conclusions here, however, are sensitive to specification and the particular data source used. While some other authors find strongly positive, significant relationships between legal immigration flows and welfare payment levels (e.g., Buckley, 1996; Dodson, 2001), others conclude the opposite (e.g., Kaushal, 2005; Zavodny, 1999). Whether immigrants locate based on welfare generosity and availability is still a subject of academic debate within economics.

Effects on Sending Countries: Brain Drain, Remittances, and Intergenerational Effects

The effects of immigration on sending and receiving countries depend on how income distributions compare and whether immigrants come from the high or low end of the skill distribution within the sending economy (Borjas, 1987). If immigrants come from the high end of the skill distribution, then we may characterize this phenomenon as positive selection. Likewise, if immigrants come from the low end of the skill distribution, then we would refer to this as negative selection. Positive or negative selection may result from differences in the rate of return to skill across locations. If immigrants are positively selected from the sending country, then economists would describe the country as experiencing brain drain.

Recent studies have suggested positive, not negative, effects on sending countries overall. Beine, Docquier, and Rapoport (2001), for example, describe two effects of migration on human capital formation and growth in a small, open developing economy. First, migration leads to increases in the demand for education as potential migrants predict higher returns abroad, and second, brain drain occurs as people actually migrate. The net effect on the sending country depends on the relative magnitudes of these effects, and cross-sectional data for 37 developing countries suggest that the first effect may dominate the second. Stark (2004) presents similar results from a model where a positive probability of migration is welfare enhancing in that it raises the level of human capital in the sending country.

In addition to changing the skill distribution in host and sending countries, migrants may affect the cross-country income distribution by remitting portions of their income abroad to family members in the sending country. These remittances may decrease the prevalence of poverty in some locations in the sending country and therefore represent additional welfare improvements. The quantity of remittances, however, may be interrelated with the presence of brain drain. Faini (2007), for example, finds evidence that brain drain is associated with a smaller propensity to remit. Although skilled migrants may make higher wages in the second country, they are empirically found to remit less than do unskilled migrants.

Other areas of literature relating to the economics of immigration examine intergenerational effects of migration. Of particular interest, increasing research has focused on the effects of immigration on subsequent generations both in host and sending countries.

Illegal Immigration and Repeat Migration

As may be expected, research on undocumented or illegal immigration is plagued by a lack of reliable and representative data. Estimates on the aggregate size of the illegal foreign-born population generally rely on residual methodology. Passel (2006a, 2006b) estimates that 11.1 million illegal immigrants were present in the United States in March 2005. This estimate is up from 9.3 million in 2002 (Passel, 2004) and 10.3 million in 2003 (Passel, Capps, & Fix, 2005). Of this total, approximately 6.2 million (56%) were from Mexico. In terms of spatial distribution within the country, 2.5 to 2.75 million illegal immigrants resided in California, followed by Texas (1.41.6 million), Florida (0.8-0.95 million), New York (0.550.65 million), and Arizona (0.4-0.45 million). These five states account for more than 50% of the estimated total. Furthermore, some immigration streams are characterized by repeat migration where, for example, migrants work for a short period (sometimes a season) before returning to their country of origin and repeat this cycle several times. Seasonal agricultural work in the United States, for example, takes this pattern where migrants (particularly from Mexico) work a season, return to their country of origin, and then return the following year.

Evidence on whether border enforcement affects the locational distribution of illegal immigrants is mixed. Some authors conclude that border enforcement causes migrants to make several attempts to cross the border as opposed to deterring migration, that the composition of illegal migrants may respond to increases in border patrol, and that the distribution of destinations may be sensitive to border patrol intensity. Others do find a deterrence effect. Orrenius (2004), for example, considers preferred border crossing sites at the state and city levels and concludes that enforcement has played an important role in deterring Mexican migrants from crossing in California. Gathmann (2008) and Davila, Pagan, and Soydemir (2002) present results supporting this conclusion. Hanson (2006) summarizes existing literature on illegal immigration from Mexico to the United States and points to areas for future research, particularly that pertaining to policies to control labor flows.

Policy Implications

History of U.S. Immigration Policy and Current Reform Proposals

Recent U.S. immigration debates have included proposals for legalization or amnesty of long-term undocumented immigrants. The Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2006 (CIRA), for example, suggested the admission of undocumented immigrants present in the United States more than 5 years, subject to the condition that these persons pay fines and back taxes. Those with 2 to 5 years of U.S. tenure would be allowed to remain in the country for 3 years, after which they would return to their countries of origin to apply for citizenship. In addition, CIRA proposed new guest worker programs. The 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) was similar. IRCA included a general program (I-687) granting legal status on the basis of continuous U.S. residence for the 5 years leading up to the program and the Seasonal Agricultural Worker (SAW) program (I-700) for farm workers employed at least 90 days in the previous year. Applications for amnesty totaled 1.8 million under I-687 and 1.3 million under I-700, and a total of 2.7 million received legal permanent residency. Applicants were first granted temporary resident status, followed by permanent residency after passing English-language and U.S. civics requirements.

Understanding the effects of legal status on worker outcomes is crucial to anticipating potential effects of a new amnesty program. Several studies document a wage gap between documented and undocumented immigrants. Borjas and Tienda (1993), using administrative data for IRCA amnesty applicants, construct wage profiles by legal status and find that documented immigrants earn 30% more than undocumented immigrants with like national origins. Rivera-Batiz (1999), using a short panel of IRCA amnesty recipients, finds that average hourly wage rates of Mexican documented immigrants were approximately 40% higher than those of undocumented workers at the time amnesty was granted. Decomposing this wage differential into explained and unexplained parts, he finds that less than 50% of this gap is attributable to differences in observed worker characteristics. Furthermore, he confirms that undocumented immigrants who received amnesty in 1987 or 1988 had economically and statistically significant increases in earnings of the order of 15% to 21% by the follow-up survey in 1992. Less than 50% of this increase can be explained by changes in measured worker characteristics over this time period. Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark (2002) find the wage penalty for being undocumented to be in the range of 14% to 24% and estimate that the wage benefit that accrued to those legalized under IRCA was around 6%. Pena (2010) estimates wage differentials between legal and illegal U.S. farm workers to be on the order of 5% to 6%. Whether workers would realize this full gain as a result of legalization, however, depends on a number of general equilibrium characteristics and is unlikely.

Amnesties have been controversial because they seem to reward lawbreaking and because they can create incentives for more illegal immigration. Although CIRA passed the U.S. Senate in May 2006, it failed to pass the House of Representatives. Alternatives to amnesty include continued increases in border security via border enforcement efforts and extensions to temporary work permit programs. These alternative proposals suggest areas for future research regarding predicted effects of immigration reform on U.S. labor markets.

Conclusion

The economics of migration is an application of microeco-nomic and macroeconomic theory. Still, given the complexity of interrelationships between host and sending countries, many questions of migration dynamics and of the causes and effects of internal and international migration are empirical ones and are the subject of debates over data sources, methodology, and conclusions. Empirical arguments such as these are hardly unusual in the social sciences. Far from being a reason for cynicism, scholarly debates are progressive— some issues get resolved while others emerge and continue to be debated—and are necessary for rational policy making. Yet it is important to note their limitations as well. The economic analysis of migration cannot answer some of the basic questions at the heart of the public debates about immigration, such as which and how many people should be allowed into a country, how their interests should be balanced against the interests of natives, and how and to what extent national identity should be preserved. These ethical and political issues can be informed by economic analysis, but ultimately they cannot be resolved by it.

See also:

Bibliography:

- Bartel, A. P. (1989). Where do the new U.S. immigrants live? Journal of Labor Economics, 7, 371-391.

- Beine, M., Docquier, F., & Rapoport, H. (2001). Brain drain and economic growth: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 64, 275-289.

- Borjas, G. J. (1985). Assimilation, changes in cohort quality, and the earnings of immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics, 3, 463-489.

- Borjas, G. J. (1987). Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants. American Economic Review, 77, 531-553.

- Borjas, G. J. (1995). Assimilation and changes in cohort quality revisited: What happened to immigrant earnings in the 1980s? Journal of Labor Economics, 13, 201-245.

- Borjas, G. J. (1999). Immigration and welfare magnets. Journal of Labor Economics, 17, 607-637.

- Borjas, G. J. (2003). The labor demand curve is downward sloping: Examining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 1335-1374.

- Borjas, G. J. (2005). The labor-market impact of high-skill immigration. American Economic Review, 95(2), 56-60.

- Borjas, G. J. (2006). Native internal migration and the labor market impact of immigration. Journal of Human Resources, 41, 221-258.

- Borjas, G. J., Freeman, R. B., & Katz, L. F. (1997). How much do immigration and trade affect labor market outcomes? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 1-90.

- Borjas, G. J., & Katz, L. (2007). The evolution of the Mexican-born workforce in the United States. In G. J. Borjas (Ed.), Mexican immigration to the United States (pp. 13-55). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Borjas, G. J., & Tienda, M. (1993). The employment and wages of legalized immigrants. International Migration Review, 27, 712-747.

- Buckley, F. (1996). The political economy of immigration policies. International Review of Law and Economics, 16, 81-99.

- Butler, R., & Heckman, J. (1977). The government’s impact on the labor market status of black Americans: A critical review. In L. Hausman, O. Ashenfelter, B. Rustin, R. F. Schubert, & D. Slaiman (Eds.), Equal rights and industrial relations (pp. 235-281). Madison, WI: Industrial Relations Research Association.

- Card, D. (2005). Is the new immigration really so bad? The Economic Journal, 115(507), F300-F323.

- Card, D. (2009). Immigration and inequality (NBER Working Paper No. 14683). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Cortes, P. (2008). The effect of low-skilled immigration on U.S. prices: Evidence from CPI data. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 381-422.

- Davila, A., Pagan, J. A., & Soydemir, G. (2002). The short-term and long-term deterrence effects of INS border and interior enforcement on undocumented immigration. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 49, 459-472.

- Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. (2008). 2007 yearbook of immigration statistics. Washington, DC: Author.

- Dodson, M. E., III. (2001). Welfare generosity and location choices among new United States immigrants. International Review of Law and Economics, 21, 47-67.

- Faini, R. (2007). Remittances and the brain drain: Do more skilled migrants remit more? The World Bank Economic Review, 21, 177-191.

- Gathmann, C. (2008). Effects of enforcement on illegal markets: Evidence from migrant smugglers along the southwestern border. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 10-11, 1926-1941.

- Greenwood, M. J. (1997). Internal migration in developed economies. In M. R. Rosenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of population and family economics (pp. 647-720). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Hanson, G. H. (2006). Illegal migration from Mexico to the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 44, 869-924.

- Hunt, J., & Gauthier-Loiselle, M. (2008). How much does immigration boost innovation? (NBER Working Paper No. W14312). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Jaeger, D. A. (2000). Local labor markets, admission categories, and immigrant location choice. Unpublished manuscript, College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA.

- Johannsson, H., Weiler, S., & Shulman, S. (2003). Immigration and the labor force participation of low-skill workers. In S. Polachek (Ed.), Worker well-being and public policy: Research in labor economics (Vol. 22, pp. 291-308). New York: JAI.

- Karemera, D., Oguledo, V I., & Davis, B. (2000). A gravity model analysis of international migration to NorthAmerica. Applied Economics, 32, 1745-1755.

- Kaushal, N. (2005). New immigrants’ location choices: Magnets without welfare. Journal of Labor Economics, 23, 59-80.

- Kossoudji, S. A., & Cobb-Clark, D. A. (2002). Coming out of the shadows: Learning about legal status and wages from the legalized population. Journal of Labor Economics, 20, 598-628.

- Lazear, E. P. (2007). Mexican assimilation in the United States. In G. J. Borjas (Ed.), Mexican immigration to the United States (pp. 107-122). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Lewer, J. J., & Van den Berg, H. (2008). A gravity model of immigration. Economics Letters, 99, 164-167.

- McKinnish, T. (2005). Importing the poor: Welfare magnetism and cross-border welfare migration. Journal of Human Resources, 40, 57-76.

- McKinnish, T. (2007). Welfare-induced migration at state borders: New evidence from micro-data. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 437-150.

- Mishel, L., Bernstein, J., & Shierholz, H. (2009). The state of working America 2008-2009. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Munshi, K. (2003). Networks in the modern economy: Mexican migrants in the U.S. labor market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 549-599.

- National Research Council. (1997). The new Americans: Economic, fiscal and demographic effects of immigration. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Orrenius, P. M. (2004). The effect of U.S. border enforcement on the crossing behavior of Mexican migrants. In J. Durand & D. S. Massey (Eds.), Crossing the border: Research from the Mexican Migration Project (pp. 281-298). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Passel, J. S. (2004). Undocumented immigrants: Facts and figures. Washington, DC: Urban Institute, Immigration Studies Program.

- Passel, J. S. (2005). Unauthorized migrants: Numbers and characteristics. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

- Passel, J. S. (2006a). Estimates of the unauthorized migrant population for states based on the March 2005 CPS. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

- Passel, J. S. (2006b). The size and characteristics of the unauthorized migrant population in the U.S.: Estimates based on the March 2005 Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

- Passel, J. S., Capps, R., & Fix, M. (2005). Estimates of the size and characteristics of the undocumented population. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

- Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2008a). Trends in unauthorized immigration: Undocumented inflow now trails legal inflow. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

- Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2008b). U.S. population projections: 2005-2050. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

- Pena, A. A. (2010). Legalization and immigrants in U.S. agriculture. The B. E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 70(1), Article 7.

- Pew Hispanic Center. (2009). Statistical portrait of the foreign-born population in the United States, 2006. Washington, DC: Author.

- Rivera-Batiz, F. L. (1999). Undocumented workers in the labor market: An analysis of the earnings of legal and illegal Mexican immigrants in the United States. Journal of Population Economics, 12, 91-116.

- Shrestha, L. (2006). The changing demographic profile of the United States (CRS Report RL 32701). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

- Sjaastad, L. A. (1962). The costs and returns of human migration. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 80-93.

- Smith, J. P. (2003). Assimilation across the Latino generations. American Economic Review, 93, 315-319.

- Stark, O. (2004). Rethinking the brain drain. World Development, 32, 15-22.

- Tiebout, C. M. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64, 4 1 6-424.

- Zavodny, M. (1999). Determinants of recent immigrants’ locational choices. International Migration Review, 33, 1014-1030.

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.