This sample Counselors Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Like other free research paper examples, it is not a custom research paper. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our custom writing services and buy a paper on any of the education research paper topics.

School counselors contribute to the academic mission of schools by delivering comprehensive developmental counseling and guidance programs to enhance the academic, career, and personal development of all students. In this research-paper, we briefly describe school counselors historically. We then clarify the current vision of school counseling and discuss the obstacles that school counselors face when they seek to implement this model. We discuss the school counselor as a person and review what is known about job satisfaction, job stability, and job prospects in this profession. We review the theoretical underpinnings of school counseling as a profession and review the methods and approaches used in practice. Since at least 1964, school counselors in the United States have been employed in elementary schools; counselors in secondary schools were common for decades before that. School counselors deliver developmentally appropriate guidance curriculum in classroom settings. They teach skills necessary for academic, career, and personal success and present lessons on topics that enhance school safety and climate. In many states and school districts, counselors have a sequential curriculum for all grade levels that includes a set of competencies or standards that students are expected to meet at each grade level. Specific objectives for reaching those standards and methods for assessing student progress are also included. School counselors also work with students individually and in small groups to help students make informed choices (e.g., courses, programs, schools, postsecondary options related to academic needs) and provide counseling to assist students with challenges that interfere with their ability to focus on academics. School counselors also consult with teachers, administrators, and parents to collect, analyze, and present data to demonstrate how they have had an effect on student progress.

Professional school counselors are represented by the American School Counselor Association (ASCA), a national organization originally chartered in 1953 as a division of the American Guidance and Personnel Association (AGPA), now known as the American Counseling Association (ACA). At the time of the foundation of ASCA, school counselors were commonly referred to as guidance counselors and it was assumed that they focused primarily on administrative tasks such as maintenance of student records. ASCA is now the largest division of ACA, with a membership of over 22,000 school counselors. ASCA has always played a key role in advocating for school counselors as central to the mission of K-12 education. School counselors have moved beyond a narrow focus on vocational guidance to a focus on high academic achievement for all students. The membership of ASCA has been instrumental in the development of professional standards, ethical guidelines, and training standards for school counselors nationwide. School counselors are thus responsible for functioning within the bounds of the Ethical Standards for School Counselors (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2004a) as well as the ACA Code of Ethics (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2005). In an effort to clarify the roles and responsibilities of the modern school counselor, ASCA developed the National Standards for School Counseling Programs (Campbell & Dahir, 1997) as well as the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2005).

The field of school counseling originated with the work of Jesse B. Davis, who implemented moral and vocational guidance activities in the early 1900s. However, Frank Parsons is most commonly credited as the “father of guidance.” His work (and that of his followers) served as part of the Progressive Movement in the United States; it focused on offering developmental services to children to provide vocational guidance and to enhance self-understanding and growth. The vocational guidance movement was intended to better prepare students for the workplace and to help children who had dropped out of school. The work of school-based counselors eventually broadened to also include personal, social, and educational concerns. Between 1930 and 1970, the field of school counseling took on mental health and personal adjustment foci and grew significantly in representation in schools due to federal acts such as the National Defense Education Act of 1958. In the 1970s, school counseling began to emphasize developmental guidance programs, inspired by the work of C. Gilbert Wrenn, that acknowledged emerging developmental theories.

Initially, school counselors were perceived to be providing services only to certain groups of students: those having personal adjustment problems and those who were college bound. Wrenn (1962) advocated that school counselors should focus on the developmental needs of all students rather than only on the needs of those who are at risk or college bound. His influence began the movement of the field of school counseling to developmental counseling.

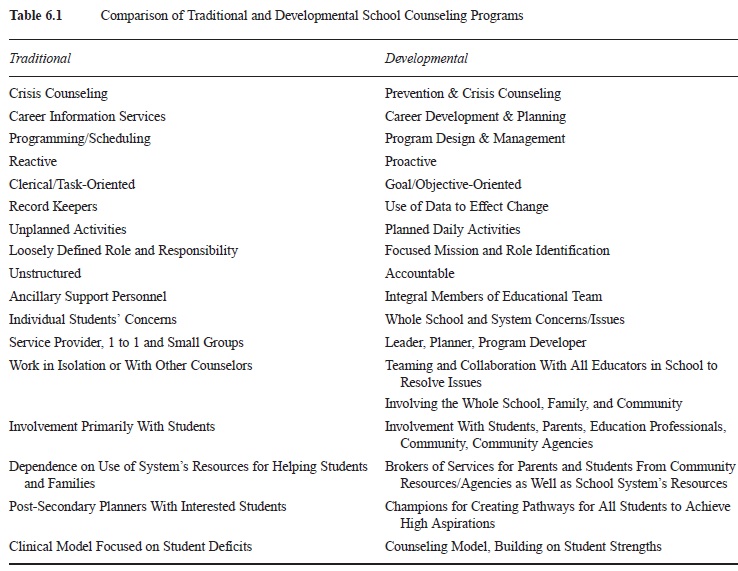

Since the early 1990s, the focus of school counseling has been on the development and promotion of comprehensive school counseling programs. This movement rests on the philosophy of Norm Gyspers and his associates, who first developed the Comprehensive Guidance Program Model (CGPM) in the 1970s (Gyspers & Hendersen, 2000; Gyspers & Moore, 1974). The developmental approach differs from the traditional model of school counseling in significant ways. Table 6.1 contrasts the two perspectives.

Table 6.1 Comparison of Traditional and Developmental School Counseling Programs

Table 6.1 Comparison of Traditional and Developmental School Counseling Programs

The overarching goals of comprehensive school counseling programs are to serve all students through the promotion of normal development and to address the challenges that arise in the lives of students through remediation and prevention. Within this framework, effective school counseling is largely measured by increases in the academic achievement of students. The ASCA National Model describes four components of the school counselor’s role: guidance curriculum, individual planning, responsive services, and system support. In response to the CGPM as well as the school reform movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s, the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) developed the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2005). The four themes of the ASCA National Model are (1) leadership, (2) advocacy, (3) collaboration, and (4) systemic change. These themes overlap as school counselors who work within this model serve as leaders engaged in promoting systemic change through advocacy and collaboration. The ASCA National Model is relatively new and thus has not been fully implemented throughout the nation.

Although CGPM and the ASCA National Model represent clear advances in conceptualizing an organizational structure for school counseling programs, these approaches have some deficiencies. The prescriptive nature of these models creates three basic problems: (1) the programs in these models are not linked to a set of identified needs, but instead are based on a preconceived set of competencies; (2) recommended interventions are not linked to expected outcomes; and (3) the evaluation of outcomes is not clearly linked to the development and improvement of interventions (Brown & Trusty, 2005). Furthermore, some assumptions and recommendations in the ASCA National Model are based more on theory and clinical lore than on research. As these concerns are addressed, it is likely that the structure and approach of the ASCA National Model will continue to evolve.

Another concern is that the expectations of administrators may not coincide with the role of the school counselor described in the model. Quasi-administrative tasks and sundry clerical chores have historically been assigned to counselors by their administrators. Individual counselors need to advocate for a program and role that aligns with current thinking about the best way for counselors to enhance student success. This will require reassignments of tasks and changes in the ways that counselors spend their time.

Because school counselors have teaching responsibilities for the guidance curriculum, states have, in the past, required that they have some experience as a classroom teacher as a condition for certification. The limited research on this question has produced evidence that school counselors with and without teaching experience are equally effective. Although only three states currently require teaching experience for school counselor certification, there remains the perception that school counselors need teaching experience to be effective, and some individual schools and districts maintain this requirement. This position maintains that schools are an educational, rather than a clinical, setting and that all personnel need to have an appreciation for the context and culture of schools. Just as school administrators typically begin their careers in the classroom, some believe that is also necessary for school counselors. Particularly in their role as consultants to teachers, it is argued that a teaching background enhances counselors’ credibility. This same line of reasoning, however, could be used to say that being a parent enhances a school counselor’s (or teacher’s or principal’s) credibility with parents; it has never been suggested that parenthood be a requirement to be an educator. We maintain that school counselors’ training and expertise, and the quality of their contributions, are sufficient to overcome these biases. Dixon Rayle (2006) found no difference in perceived job stress and the sense that they mattered to others between school counselors who had been teachers and those who had not, and also reported greater job satisfaction in school counselors who had not been teachers.

Interestingly, school counselors are trained in master’s degree programs that have the same core requirements as those for counselors in mental health and counseling settings. The differences in training commonly are the addition of a few school counseling-specific courses and the practicum and internship experiences, which are in the K-12 school setting. The core requirements for master’s degrees in counseling are: Human Growth and Development, Counseling Theories, Individual Counseling, Group Counseling, Social and Cultural Foundations, Testing/ Appraisal, Program Evaluation, and Career Development. These requirements are established by the Council for Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP), which grants approval to graduate training programs. Most programs, even if they are not CACREP approved, follow the basic requirements that CACREP has established.

The Person and the Job

School counselors are interested in helping others. They are understanding, compassionate, good listeners, and they are sensitive to others’ feelings and needs. To be successful, school counselors need to be adaptable and flexible to deal with a variety of situations and people. They must be good at collaborating and have a high tolerance for stress. They need to have excellent communication skills, and they should be resourceful in gathering information and solving problems. Although some school counselors are former teachers, often those to whom students are drawn to discuss personal concerns, others made career changes because of a desire to improve the lives of children and a conviction that schools are places to reach many children.

Although national data are not available, research reporting demographics of school counselors consistently finds the vast majority of current school counselors are Caucasian females. Also, in many studies, the largest age group is 50 and above.

While the work setting is the same for all school personnel, counselors often have longer days or school years.

The need to meet with parents (who may be unable to miss work for meetings during school hours) and others, and to accomplish other record-keeping or data-collection tasks while being available to students and staff during regular school hours, may mean arriving early or leaving later than classroom teachers. Duties for registration of new students often begin before teachers report for duty in the fall and extend beyond the end of the school year. Counselors are generally paid for the extended-year period, but districts and states vary in whether they compensate counselors on the teachers’ salary scale or a separate scale.

Data from 2004 indicated that the median annual salary for elementary and secondary school counselors was $51,160, which was the highest among counselors across settings (Ruhl, n.d.). In 2003-04, there were 60,800 employed in elementary schools and 40,600 working in secondary schools. Almost a third of elementary counselors were part-time, compared to only 6% of secondary counselors (National Center for Education Statistics, 2007). Elementary counselors had an average caseload of 372 students, while secondary counselors worked with an average of 321 students. Elementary counselors are generally the only counselor in the school (and many work part-time in several schools), while secondary counselors are generally part of a counseling department. School counselors in high-poverty schools had somewhat larger average caseloads (380) than those in low-poverty schools (346).

Several studies have examined job satisfaction and stability among school counselors. One source (Ruhl, n.d.) reported that 60% of new school counselors leave the field within two years. DeMato and Curcio (2004) surveyed members of the Virginia School Counselor Association who worked in elementary schools; they were interested in changes in job satisfaction after a state requirement mandating elementary school counselors was dropped, and mandated high-stakes testing was implemented. Previous surveys (1988 and 1995) had found that 93.4% and 96.3% of elementary school counselors were satisfied with their jobs, respectively. DeMato and Curcio reported that 91% of elementary school counselors surveyed were satisfied or very satisfied with their jobs. As in the previous studies, the only source of job satisfaction that was rated in the “dissatisfied” range was compensation. Baggerly and Osborn (2006) surveyed elementary and secondary school counselors in Florida and reported that 85% of their sample was satisfied or very satisfied with their jobs. However, 13% of participants were undecided about whether they would continue in the career, and 11% were planning to quit or retire. On average, the counselors in this sample perceived increased job stress in the previous two years, with middle and high school counselors reporting a greater increase in stress than elementary counselors.

The only national survey of job satisfaction among school counselors found that elementary-level counselors were most satisfied with their jobs and experienced the least degree of job-related stress of all levels (Dixon Rayle, 2006). High school counselors were the least satisfied with their jobs, had the highest levels of job-related stress, and had the lowest levels of perceived mattering to others. Middle school counselors reported the highest levels of perceived mattering. They reported that they mattered most to students and least to teachers with whom they worked, while elementary counselors perceived they mattered most to the parent group.

The U.S. Department of Labor (2006) projects that employment for school counselors will grow at least as much as the national average through 2014. Factors that bode well for the future are increasing numbers of states mandating elementary school counselors and increased responsibilities of school counselors. Budgetary constraints, however, are likely to work against job growth, unless grants and subsidies provide increased support for school counseling positions. Rural and inner-city schools are likely to see the greatest job growth for school counselors.

Theory

Today’s school counselor works to deliver a comprehensive developmental school counseling program. These programs are defined as (a) comprehensive in scope, (b) preventive in design, and (c) developmental in nature (ASCA, 2005). In theory, programs that are comprehensive in scope focus on the needs of all students, K-12, with an emphasis on students’ academic success and successful development. School counseling programs are preventive in design in that they teach students the skills and provide them learning opportunities that empower them with the ability to learn. School counselors deliver programs of preventive education that provide academic, career, and personal/social development experiences. Comprehensive developmental school counseling programs are designed to meet the needs of students throughout all developmental stages. Services are sequentially planned in order to meet the needs of children and adolescents as they progress through the developmental pathways.

The philosophy of developmental counseling provides the basic assumptions on which the field is based. These assumptions are as follows:

- Students normally develop in ways similar to those of others their same age.

- Despite these similarities, each student’s needs are based on a unique combination of individual, cultural, and contextual variables.

- If students are offered a curriculum that is both developmental and preventive in nature, they will be able to develop life skills that enhance their ability to communicate effectively, resolve conflicts, make good decisions, act responsibly, and live fulfilling lives.

- The school counselor has the responsibility for the design and implementation of the developmental school counseling program.

- A coordinated approach to school counseling ensures that (a) the skills and training of the counselor are used to optimum advantage, (b) the invaluable work of social workers, nurses, and psychologists interface effectively with the counseling program, (c) the classroom teacher’s important role in guidance is strengthened, and (d) parents, caregivers, and other community resources are kept informed and urged to participate more actively in the education of children.

- School counselors take a systems perspective on helping students. They are involved in shaping school climate, implementing preventive programs, and advocating for the needs of all students.

- School counselors are most effective when they respond to students’ needs with individual, group, and classroom guidance approaches based on the assumption that as individuals grow, they encounter developmental challenges that, if met, enable them to act in ways that best serve them and society responsibly and positively.

- The counseling program and its components need to be systematically and regularly evaluated for effectiveness. Changes to the program and services rendered should be made regularly in response to these evaluations.

School counselors commonly divide their work into three domains of focus: career, academic, and personal/ social development. Career development focuses on the acquisition of skills, attitudes, and knowledge that prepare students to transition from school to work and from job to job across the lifespan. Counselors provide services to help students understand and respond well to the intersection of their personal qualities, training, and education with their career choices. School counselors focus on the academic development of all students and focus on providing services that maximize students’ ability and desire to learn, helping them make connections between their academic development and their personal and career development, and ultimately make informed decisions regarding their futures. Finally, it is important for counselors to address students’ personal and social development.

Methods Used by School Counselors

Individual Counseling

School counselors provide many services to students and are trained to use various methods and approaches to support the development of students. One of the methods they use is individual counseling, or one-on-one meetings with students. Sometimes such meetings focus on academics, such as reviewing the student’s progress toward graduation, reviewing scores on standardized tests, making decisions about courses to take, and sorting out post-high school options. School counselors also provide individual counseling focused on personal or social concerns. Students are referred to school counselors (or refer themselves) when personal concerns interfere with their ability to focus on academics. School counselors have training in basic counseling skills just as do mental health counselors, and they are well-trained to work with individual students who need support. School counselors exhibit the core conditions identified by Carl Rogers (1957), which are believed to create the climate necessary for counseling to be helpful: empathic understanding, congruence/genuineness, and unconditional positive regard.

School counselors also learn basic counseling theories, skills, and techniques. Some rely on a particular counseling theory to guide their practice, while others may integrate techniques from a number of theoretical perspectives. Counseling theories that are particularly suited to the school setting include Brief Solution-Focused Counseling (BSFC), Reality Therapy (now known as Choice Theory), Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT), and other Cognitive Behavioral Theories. In the school setting, however, where the focus is on academics and the national average school counselor-to-student ratio is 479:1 (with 229:1 at the high school level and 882:1 at the elementary level), school counselors are unable to provide long-term ongoing counseling to individuals. In some urban settings, this ratio can swell to over 1,000 high school students to one counselor. These ratios include schools with no counselors in the calculations; many elementary schools do not have school counselors on staff. In many schools, counselors will meet with an individual student a limited number of times (often established by district policy) and refer those who need more intensive services to providers in the community. School counselors do not turn away students in need, but help manage the urgent situation while assisting them in obtaining long-term professional help.

When students with behavioral problems are referred to the school counselor, the counselor does not function as a disciplinarian. Rather, the counselor will help the students with personal issues that may be causing the inappropriate behaviors. If the problems cannot be resolved in a few meetings, the school counselor may refer the student for outside services or to the child study team in the school to consider other strategies for helping the child behave more appropriately.

Group Counseling

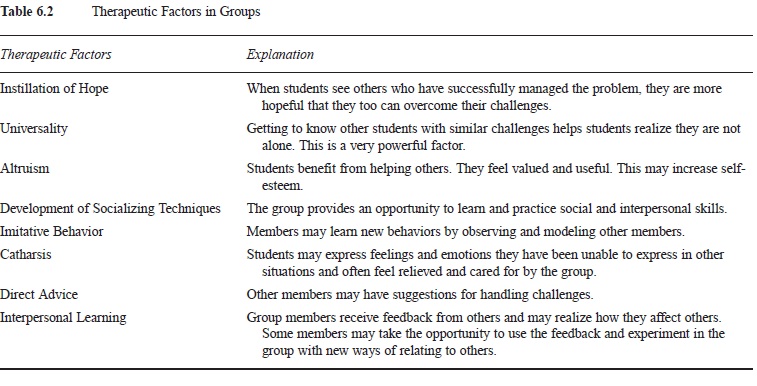

Group counseling is another method used by school counselors. Working with a small (3-10) group of students who share common concerns is not only a more efficient use of counselor time, but may be more effective. Groups provide the opportunity for members to learn from each other and to practice skills with peers. Yalom and Leszcz (2005) described a set of curative or therapeutic factors that explain the effectiveness of groups. Those that are most applicable to school groups are listed in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2 Therapeutic Factors in Groups

Table 6.2 Therapeutic Factors in Groups

Groups are appropriate at all school levels, but the length and format must be adjusted to fit capabilities and needs of participants. At the elementary level, groups will typically have fewer members (3-5) and meet for shorter periods (20-30 minutes), sometimes more than once per week. Middle school groups can be effective with up to 8 members, and meetings of 45-50 minutes, usually coinciding with class periods, are the usual schedule. Middle school groups may have weekly meetings for 6-8 weeks. Groups in high schools may have up to 12 members, and they may meet weekly for a semester or longer, depending on the needs of the group and availability of time.

With the emphasis on academic achievement, teachers and administrators may be reluctant to release students from classes to attend groups. Counselors need to respond to this challenge in several ways by educating the stakeholders in the ways in which personal issues interfere with learning, by collecting and analyzing data that demonstrate the positive outcomes of the groups, and by using creative scheduling strategies to protect students’ time in class (meeting during lunch or before or after school) although these arrangements may not be ideal. Other counselors arrange a rotating schedule for groups so that students do not often miss the same class or activity.

Groups in schools are usually either psychoeducational groups or counseling groups. Psychoeducational groups, or guidance groups, have the goal of imparting needed information to generally well-functioning individuals. The small group format allows information to be presented, discussed, and often practiced using a variety of skill-building exercises. These groups are usually structured around a particular focus, such as stress management, body image, divorce, substance abuse prevention, and so forth. Some schools offer groups for students whose parents are in the military or for students who have an incarcerated parent. Students who are invited to participate in guidance groups are usually considered at risk for developing problems, and the group is designed to prevent problems from developing. Psychoeducational groups are geared toward prevention.

Counseling groups help students who are experiencing problems and focus on providing support, feedback, and problem solving. Some of the topics mentioned for guidance groups may also be the focus of counseling groups, but there is less focus on providing information and more emphasis on providing emotional support and addressing problems that are occurring as a result of these situations. Most school counseling groups assist students to recognize and use their strengths and resources. Some counseling groups have little structure, allowing students to bring up issues that concern them in the moment. These groups are used more often with older students. Other groups incorporate a focus on changing self-defeating behaviors, helping members apply such changes outside the group, and improving interpersonal skills. School counselors help group members develop norms for behavior in the group, which always include confidentiality and respect for others. Counseling groups may be offered to students who have experienced a loss, who have a difficult family situation, who have been victimized in school, or who have had substance abuse problems. Parental permission is generally required when students participate in groups at school.

Classroom Guidance

Classroom guidance lessons are planned and delivered by school counselors in the classroom setting. Here the counselor serves all students, not merely those in crisis. The lessons are focused on teaching related to the personal/social, academic, and career domains. Counselors are educated about human development, and they consider needs of students at different stages of development when designing lessons. School counselors develop guidance curricula that are based on sound developmental and educational principles. Often counselors have a regular schedule of classroom visits and presentations that are designed to teach useful skills and behaviors. Experts recommend that guidance curricula be aligned with academic areas and include identified goals, objectives, specific competencies, and standards by which students’ achievement of the competencies can be measured.

Elementary and middle school counselors spend much of their time doing classroom guidance lessons (35%-40%); whereas high school counselors spend less (20%). Topics vary with age. Elementary lessons may teach students about friendship, conflict, making choices, etc. At middle and high school, the focus shifts to more academic issues, such as selecting courses, test anxiety, effective interpersonal communication, etc. Typically, classroom teachers remain in the classroom and are then able to reinforce the lessons presented by the counselor.

The guidance curriculum may include prevention programs that focus on issues that interfere with student learning and with leading productive lives. Many schools are concerned about school violence and bullying and substance abuse, and the counselor is often the most prepared and best-informed person to coordinate school efforts to prevent such problems. Presenting classroom lessons enhances the visibility and credibility of the counselor. Thus, students who have needs are more likely to approach the counselor. Through frequent classroom participation, counselors also have an opportunity to observe students and note those that may need other services (individual or group counseling) without waiting for the student to seek out the counselor.

Consultation

Consulting means the counselor works with someone other than the student in order to help the student. The person with whom the counselor consults might be a classroom teacher, an administrator, a caregiver, or a member of an outside agency that is working with the student. The goal of the consultation is to help the student. The school counselor uses his or her expertise and communication skills to provide help and information that will allow others to better serve the student.

The school counselor may gather information about the student to get a more complete picture of the student’s needs. If a student is referred to the counselor because of classroom behavior problems, the counselor may consult with teachers and parents in addition to meeting with and observing the student. The counselor may also work with teachers to implement different strategies that might change the student’s behavior. At an IEP, 504, or child study team meeting, the counselor consults with team members and offers suggestions. The school counselor is an advocate for the student, ensuring that the student’s interests are represented and that the outcomes are appropriate for the situation and the child. The counselor can also serve as a consultant to the entire school, and often does so when engaging in activities or plans to improve school climate or implementing new programs.

Outreach

School counselors might request outside agencies to assist the school in projects, such as arranging for guests at school career fairs or soliciting shadowing experiences for students interested in a particular career. Outreach also involves identifying outside programs, agencies, and opportunities for students. There may be special programs, summer opportunities, or correspondence and online courses about which the counselor gathers and disseminates information.

Family outreach is particularly important. Various strategies are used to engage families (open house events, career days, and parent-teacher conferences). While popular, these activities typically reach only some families, so school counselors use other strategies to communicate with families. Welcome letters sent to students when the year begins introduce school counselors and emphasize their interest in forming partnerships with families. Packets, flyers, and other materials about the school counselor are provided with the letter. Some counselors distribute calendars on which important counseling-related events are noted and use newsletters to advertise activities and make announcements.

School counselors establish relationships with key community resources that reflect and represent the cultural diversity of the school. Both formal and informal community resources may be needed, and maintaining ongoing relationships with “cultural brokers” who can assist with translation and serve as a liaison to diverse communities facilitates the process.

School counselors are in an excellent position to change negative perceptions that some parents and caregivers hold of the school by making home visits or telephone calls to families when problems are not the focus. This conveys the message that the counselor is interested in the positive accomplishments of students, not just negative behaviors. Such activities are particularly useful when parents’ or care-givers’ jobs, transportation and child care concerns, and other obstacles make it difficult for them to come to school. School counselors in schools where parent participation has historically been low may incorporate innovative elements to bring them to the school. Providing meals, holding raffles for goods and services, and providing child care at events are often successful at increasing participation. These strategies involve outreach to community partners, who may donate food or services for these occasions.

In many communities regular meetings of all human service agencies are held, and school counselors attending these meetings can establish personal networks with other professionals. This creates a pool of resources to call upon when needs arise and provides an opportunity for school counselors to educate other agencies about students.

Crisis Response

A crisis—as defined by school counselors—is an unpredictable event outside the normal school experience that creates extreme stress and disrupts the normal functioning of many students and staff in the school. The event might occur outside the school, but if it affects the school, a crisis response is needed. Typically, school counselors are members of a crisis response team and often serve on district-level crisis response teams. Because of their knowledge of students and staff, school counselors are in a unique position to provide crisis response services and to advise administrators. Teachers often need support during and after a crisis, and counselors can provide teachers with accurate information and even prepare written instructions or scripts for communicating information to students. Counselors may conduct classroom discussions related to the crisis and provide support and referrals to teachers who are personally affected. Counselors use their knowledge of students to identify those most likely to need additional or emergency mental health services (typically those closest physically to an incident or emotionally to a deceased student or staff). They then make appropriate referrals and expedite those for students at high risk. They also often contact families to make them aware of the crisis and the need for close attention to their child. For many students, support groups and brief individual counseling with the school counselor will be sufficient. Counselors also monitor affected persons over the long term because a crisis has both immediate and long-term consequences that vary among exposed individuals.

School counselors strive to build trusting relationships with parents and guardians. These relationships position the counselor as the person that caregivers will best respond to when they need to be informed of a crisis. School counselors also ensure that the school’s response is culturally appropriate and sensitive. For example, when there is a death of a student or staff member, school counselors demonstrate cultural awareness by responding to students and their families in a culturally sensitive manner. They may call upon outside agencies (or counselors from other schools) for assistance in a large-scale crisis. Having well-established relationships with those agencies and personnel expedites that process.

Using Data

School counselors frequently use data and have responsibilities for coordinating the administration of standardized tests. They are skilled at helping students and parents understand and interpret test results so that they can use them effectively. They are able to assist teachers and administrators in using assessment results appropriately.

School counselors also use specialized tests that help students make informal decisions. Aptitude tests (such as the Armed Forces Vocational Aptitude Battery) and tests required by colleges (Scholastic Aptitude Test and the American College Test) are examples of such tests. School counselors may also administer career interest inventories to assist students in planning future courses and career paths, and sometimes they use other inventories to enhance students’ awareness of different personality styles (e.g., the True Colors system).

School counselors, and all other education professionals, must demonstrate that they contribute to student achievement. The American School Counselor Association (2005) asserts: “Professional school counselors use data to show the impact of the school counseling program on school improvement and student achievement.” The recent emphasis on accountability has elevated the importance of this function.

While school counselors have often collected self-reports and personal feedback from students, parents, and teachers about services they have received, such data are less useful than measures with adequate psychometric properties (meaning they have demonstrated reliability and validity). When implementing programs, counselors might collect pretest and posttest data to find out whether the students have learned the material or made anticipated changes as a result of the program. Ideally, they use control or comparison groups to ensure that the observed changes are the result of the new program and not simply the result of something else.

School counselors collect, summarize, and present data to various stakeholders. They are careful to ensure their data collection procedures and analyses are clear and accurate, since important decisions are often made based upon such data.

Application

Imagine that a school suspects that bullying at school is interfering with students’ ability to focus on academics. The school counselor provides skills to assist the school in reducing the incidence of bullying.

School counselors gather accurate information about the prevalence of bullying and the situations and locations where it occurs. Using this information, school counselors reach out to others in the school community, including parents, caregivers, and students, to form a committee to oversee efforts to improve it. Counselors consult with colleagues and the professional literature to obtain current information about existing programs, and the committee selects the program most beneficial for their needs. Once a program is selected, school counselors often train the school staff in how to use the program. School counselors help the school create or enhance a positive school climate, and they include curricular components of the program in the guidance curriculum. Despite hard work, it is unlikely that the problem will be eradicated immediately. School counselors therefore intervene with individuals affected by bullying, providing support and assertiveness skills training to victims, empathy training and anger management skills to bullies, and help-seeking skills to bystanders. Counselors engage caregivers, who need information about the program, and provide suggestions for responding at home and notification when children are involved in bullying incidents at school. In the event of a crisis related to bullying, as has unfortunately occurred in recent years, school counselors commonly implement crisis response protocol.

Future Directions

Although the ASCA National Model is widely disseminated among school counselors, there is not universal agreement that this is the best approach. Some critics argue that the model currently is not flexible enough to adapt to individual schools, whose needs vary by setting (urban, suburban, rural), availability of resources, and local philosophies of education. Others contend that administrators are reluctant to free school counselors from quasi-administrative and clerical tasks. Comprehensive developmental programs will not be implemented if administrative support is lacking, despite state adoptions. Further, the model has been criticized for insufficient emphasis on cultural diversity and for ignoring the mental health functions school counselors can provide. Who will provide mental health services and programs for at-risk youth if the school counselor is providing more broad-based services to all students? Dixon Rayle (2006) in a national sample of school counselors at all levels found that those who had implemented comprehensive competency-based programs believed they mattered more to others at work and had significantly greater job satisfaction than those who were not using comprehensive programs. School counselors and administrators need to work together to decide whether the comprehensive developmental program is an appropriate model for all schools, and if so, how local needs and diversity can be addressed within the model.

School counselors are likely to be encouraged to take a larger role in special education programs (ASCA, 2004b). In addition to helping to identify students who may be eligible for these services, school counselors are increasingly involved in helping teachers accommodate students who receive special education services and in efforts to smooth the school-to-work transition for these students. They will continue to play an essential part in supporting and advocating for these students, and they will be engaged in assessing the needs of these students and providing services as needed. Finally, school counselors’ guidance curricula will assist all students by promoting respect for diversity.

As educators increase attention to critical transition points (elementary to middle school, middle school to high school, and high school to postsecondary school or work), school counselors will be taking on more responsibilities for planning and implementing effective programs to help students make these adjustments. The most critical need in the future of school counseling is for outcome research on school counseling services that uses rigorous scientific methods. Soft data, such as testimonials about a program, will no longer be sufficient to justify programs. School counselors and counselor educators need to collaborate to produce and disseminate the kind of research that satisfies the demands for accountability in education.

Conclusion

We have reviewed the evolution of the school counseling profession from its origins in the vocational guidance movement at the turn of the 20th century to its current emphasis on comprehensive developmental programs for all students. We noted that school counselors are no longer isolated from the activities of the school, but now occupy central leadership roles. Although school counselors once focused on college-bound students and student in crisis, contemporary school counselors provide a range of services, including the delivery of a classroom guidance curriculum that is sequential and competency based.

The profession of school counseling is anchored in philosophical propositions that provide a coherent rationale for school counseling services. School counselors believe that the developmental process is universal, although the unfolding of developmental events varies among students. They see children and schools from a systems perspective; that is, they recognize that individuals do not exist in a vacuum, but affect and are affected by others and their environment. Modern school counselors have a strengths-based, rather than a deficit-focused, perspective on student needs and development.

Most school counselors are satisfied with their jobs, but job-related stress has increased in recent years. Job prospects for school counselors are at least average, and compensation is higher than that of other counseling specialties. We described the many strategies and approaches used by school counselors in their work and gave an example of how their many roles often intersect in addressing school bullying. In this research-paper, we argued that school counselors are leaders in schools; they are strong advocates for students, concerned about school climate and working to create a positive and inclusive atmosphere in which all students flourish. They work collaboratively with others in the school and in the community to enhance student success. We clarified that school counselors need to collect and disseminate data that demonstrate their effect on the educational outcomes of students.

We discussed two controversial issues in the field: the development and implementation of the ASCA National Model and the question of the need for teaching experience for school counselors. These issues are likely to continue to be important in the future.

See also:

Bibliography:

- American Counseling Association. (2005). ACA code of ethics and standards of practice. Alexandria, VA: Author.

- American School Counselor Association. (2004a). Ethical standards for school counselors. Retrieved August 2, 2007, from http://www.schoolcounselor.org/files/ethical%20 standards.pdf

- American School Counselor Association. (2004b). Position statement: Special-needs students. Retrieved April 10, 2008, from http://www.schoolcounselor.org/content.asp?contentid=218

- American School Counselor Association. (2005). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs. Alexandria, VA: Author.

- Baggerly, J., & Osborn, D. (2006). School counselors’ career satisfaction and commitment: Correlates and predictors. Professional School Counseling, 9, 197-205.

- Brown, D., & Trusty, J. (2005). Designing and leading comprehensive school counseling programs: Promoting student competence and meeting student needs. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

- Campbell, C. A., & Dahir, C. A. (1997). The national standards for school counseling programs. Alexandria, VA: American School Counselor Association.

- Coleman, H., & Yeh, C. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of school counseling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- DeMato, D. S., & Curcio, C. C. (2004). Job satisfaction of elementary school counselors: A new look. Professional School Counseling, 7, 236-245.

- Dixon Rayle, A. (2006). Do school counselors matter? Mattering as a moderator between job stress and job satisfaction. Pro-fessional School Counseling, 9, 206-215.

- Erford, B. T. (2003). Transforming the school counseling profession. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Gyspers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2000). Developing and managing your school guidance program (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

- Gyspers, N. C., & Moore, E. J. (1974). Career guidance, counseling, and placement: Elements of an illustrative program guide (a life career development perspective). Columbia,

- MO: University of Missouri. Herr, E. L. (2001). The impact of national policies, economics, and school reform on comprehensive guidance programs.

- Professional School Counseling, 4, 236-245. National Center for Education Statistics. (2007). The condition of education. Retrieved July 31, 2007, from http://nces.ed.gov/ programs/coe/2007/section4/table.asp?tableID=727

- National Center for Transforming School Counseling at The Education Trust. Retrieved April 10, 2008, from http://www2.edtrust.org/EdTrust/Transforming+School+Counseling/main.x

- Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95-103.

- Ruhl, C. (n.d.). Becoming a school counselor. Retrieved July 31, 2007, from http://www.education.org/articles/becoming-a-school-counselor.html

- Schmidt, J. (2002). Counseling in schools: Essential services and comprehensive programs (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Sciarra, D. T. (2004). School counseling: Foundations and contemporary issues. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

- Thompson, R. A. (2001). School counseling: Best practices for working in the school (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Brunner-Routledge.

- United States Department of Labor. (2006). Occupational Outlook Handbook. Retrieved April 10, 2008, from http://www .bls.gov/oco/ocos067.htm#outlook

- Wehrly, B. (1981). Developmental counseling in United States schools: Historical background and recent trends. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 4(1), 51-58.

- Wrenn, C. G. (1962). The counselor in a changing world. Washington, DC: American Personnel and Guidance Association.

- Yalom, I., & Leszcz, M. (2005). Theory and practice of group psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

- Zytowski, D. G. (2001). Frank Parsons and the progressive movement. The Career Development Quarterly, 50, 57-65.

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.