This sample Activist Group Tactics Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Firms are entities with a considerable influence on social life. They affect wealth and welfare by offering jobs to workers, selling services and products to consumers, paying dividends to shareholders, and discharging wastes on nearby communities. However, firms are not necessarily held to be responsible to all of these, and other, stakeholders, other than as required by law. In fact, in the United States, firms are first and foremost held to serve the interests of their owners. Yet, if firms were to pursue the interests of their owners without any regard for the interests of workers, consumers, and communities—that is, if they were not to accept social responsibility commensurate to their social power—they are likely to lose business power because other actors may step in and enforce what managers fail to take responsibility for. Therefore, firms and their managers are advised to pay attention to a set of interests that is broader than profits and share prices. Fifty years ago, Keith Davis stated it this way: “Businessmen during the next fifty years probably will have substantial freedom of choice regarding what social responsibilities they will take and how far they will go. As current holders of social power, they can act responsibly to hold this power if they wish to do so. . . . The choice is theirs” (Davis, 1960, p. 74).

In 1960, Davis was thinking of the state—defender of the poor and oppressed, provider and protector of public goods—and of trade unions—protectors of workers’ rights and, perhaps, the more or less established channel for the expression of anticapitalist ideology and rhetoric—as those actors who were likely to step in. Since the 1960s, but particularly since the 1990s, it has become increasingly evident that other groups were stepping in. Examples include the continuing campaigns by human rights activists and other groups to improve labor conditions in the global supply chains of apparel companies such as Nike, and the short but fierce campaign conducted by Greenpeace against Shell, regarding the intended deep-sea disposal of the Brent Spar oil rig in 1995. David Baron (2003) refers to this phenomenon as “private politics.” These politics are private as the attempts that different groups make to influence corporate decision making and economic activity are directly oriented toward firms and trade regimes without reliance on public institutions or officeholders, thus bypassing law making or law enforcement. Following this definition, we do not consider political lobby and lawsuits in this research-paper, although legal routes are often used and potentially highly effective tactics that therefore are an indispensable part of their tactical repertoire.

Thus, how such groups (try to) influence firms has been an increasingly significant theme over the past few decades and is likely to remain prominent in the years ahead. Yet, their apparent influence remains difficult to understand, because from the firm’s perspective, such groups lack a well-developed basis for negotiation and bargaining (De Bakker & Den Hond in press). Following this line of reasoning, we discuss how such groups try to influence firms, and whether the way in which they do so today is different from the past.

Before we can take up these two central questions, we need to discuss what we mean by “such groups,” which are likely targets for their activism and the various tactics they may use. Next, we distinguish between several influence mechanisms by which pressure may be exerted upon firms. We conclude this research-paper with discussions of the research into the efficacy, and the novelty, of current corporate campaigns.

Defining The Object Of Interest

To make explicit what we mean by “other groups” is not an easy task because a wide variety of relevant labels and definitions are found in the literature. Some are quite restrictive, excluding relevant groups while others are almost catch-all labels. For example, the often-used label “nongovernmental organization” includes sports clubs, church organizations, private interest groups, and even the mafia, but most of such groups never bother with private politics as it has been defined by Baron (2003). How then do we define the groups that influence firms?

Some have referred to the agents of private politics in terms of what they are not. They are not governmental organizations, and they are not for-profit organizations. Such parlance is often used in settings of transnational policy making in order to emphasize their independence from nation states and corporate interests. Schepers (2006, p. 283) distinguishes between nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that aim to provide assistance to those in need (direct-aid NGOs), that strive to help local communities in their efforts to establish local change (empowerment NGOs), and that try to influence either government or business policy formation or conduct (advocacy NGOs). Parker (2003) points at the existence of “hybrid” NGOs, which combine operational work and ambitions with advocacy means in order to establish some social benefit.

Others have referred to such groups by emphasizing particular characteristics. For example, Eesley and Lenox (2006) and De Bakker and Den Hond (in press) refer to such groups as “secondary stakeholders.” They emphasize the lack of a contractual bond between such groups and the firm, the absence of a direct legal authority over the firm, and a nonexistent or very weak established bargaining position vis-à-vis the firm. Adopting stakeholder language may obscure the considerable heterogeneity in the interests and identities among the members of, or subgroups within, a particular stakeholder group (Rowley & Moldoveanu, 2003).

Den Hond and De Bakker (2007) speak of “activist groups” in order to emphasize their propensity to organize campaigns around themes that they deem important. Keck and Sikkink (1998) refer to “transnational activist networks” to emphasize the extensive patterns of resource exchange and mutual support (networks) that have developed between tens of dozens of such groups from all over the world. These activists who “seek to make the demands, claims, or rights of the less powerful win out over the purported interests of the more powerful” (Keck & Sikkink, 1998, p. 217). Yet others speak of “interest groups” (Moe, 1981), thereby focusing on the particular single interests that such groups pursue and implicitly criticizing them for undermining the democratic system. Contrary to such notions, to refer to them as “civil society groups” emphasizes their role in creating and maintaining social capital and highlights their role in democratic processes (Scholte, 2004).

Such variety in terminology partly reflects the particular preoccupations of individual authors regarding their objects of study, and partly demonstrates the enormous variety among such groups that is indeed empirically found. By emphasizing certain characteristics over others, bias, confusions, and distortion are inevitably introduced; in that sense, “such groups that aim to influence firms” may be beyond unequivocal and uncontested definition. For the purposes of this research-paper, we choose to adopt the term “activist group,” as we wish to highlight the intention of these groups to exert influence over corporations, and their willingness to make sacrifices to realize their ambitions such as investing resources and time or bearing risk. Yet we retain essential characteristics of several other concepts: their lack of bargaining power vis-à-vis the firm (the secondary stakeholder concept), their independence from the state and corporate interests (the NGO concept), and their claim to represent underrepresented groups and interests (the civil society group concept).

What Firms Do Activist Groups Wish to Affect?

Which firms are at a higher risk of being challenged by stakeholder groups? Different authors have theorized about this question. Frooman (1999) argues that as firms are more dependent on stakeholder support, either direct or indirect, these stakeholders gain influence over the firm. Rowley and Berman (2000) theorize some broad conditions that mobilize stakeholders, including characteristics of the focal organization (such as size), precipitating issues (such as accidents), industry characteristics, and the surrounding stakeholder environment. When taking the perspective of the firm, there seems to be some consistency in the suggestions that both proven, repeated wrongdoers and larger and more visible firms are at a greater risk of stakeholder scrutiny, and even more so if they operate in advertising-intensive industries or in environmentally or socially sensitive industries (cf. Hendry, 2006, for activism regarding environmental issues, and Rehbein, Waddock, & Graves, 2004, for shareholder activism). Conversely, such firms are also more likely to invest in corporate social responsibility (McWilliams & Siegel, 2001).

The picture may change, however, when taking the perspective of activist groups. Building on social movement and identity theories, Rowley and Moldoveanu (2003) suggest that identity-based groups and interest-driven groups have different motives for targeting firms, and therefore may select different firms as their targets. There is also differentiation in the choice of tactics among activist groups. For instance, Carmin and Balser (2002) find different tactical choices among Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, and relate this to their political ideologies and environmental views, whereas Den Hond and De Bakker (2007) suggest that ideological differences among activist groups motivate them to choose different influence tactics to support their claims. Of course, such differences may also affect which firms stakeholder groups are more or less likely to target.

A Classification Of Influence Tactics

The influence of activist groups over firms has been analyzed from various perspectives, with diametrically opposing assumptions. For example, from sociology (social movement studies) and political science emphasis has been placed on the conflict of interests, thus depicting their relationship as fundamentally adversarial (Keck & Sikkink, 1998; Micheletti, 2003). Conversely, in the tradition of stakeholder management, the potential benefits of cross-sector alliances have been highlighted; their relationship is seen as productive with a potential for win-win solutions ([WCED], 1987; Westley & Vredenburg, 1991). Yet, some stakeholder groups assume both roles, sometimes presenting themselves as adversaries and other times as partners. For example, Greenpeace is renowned for its confrontational tactics, but has also worked with industry, for instance in developing new technological solutions that fit with its ideological position such as a CFC-free refrigerator. Therefore, collaboration and confrontation must be viewed as two broad strategic options for activist groups to pursue their interests Irrespective of whether a collaborative or an adversarial track is chosen, a first step for activist groups is to collect, organize, and disseminate information and formulate desirable outcomes. Often, an early step in a campaign is to inform a firm’s management of the particular concern—including the motivating moral outrage—and propose a desirable outcome or alternative course of action. Evidence is provided to substantiate the reasons for concern, such as labor issues or environmental issues, and the moral superiority and practical viability of the proposed alternative is contended. If this is the common pattern by which activists and firms start their engagement, the question is, then, how activist groups may leverage their claims if the firm responds defensively to their claim (e.g., by window dressing, denying the charges, or rejecting responsibility)? Moral appeal, or the “logic of appropriateness” (March & Olsen, 1989), may not provide sufficient incentives for firms to change their practices.

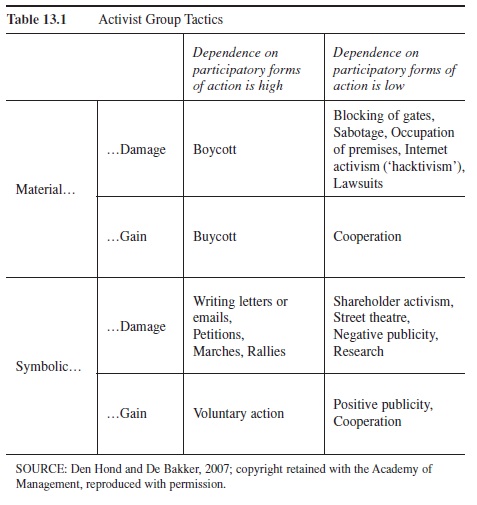

Table 13.1 provides some examples of the broad range of tactics that has been described in the literature. Tactics are often classified on a dimension from being conventional and relatively nondisturbing to being unconventional and highly disturbing or even violent, thus including a suggestion of escalation. However, Den Hond and De Bakker (2007) point out that there are costs and benefits associated with the use of different tactics and that the balance of costs and benefits may be different for different activist groups, such that they have different routes during the escalation or persistence of a conflict. Although activist group tactics could also be fitted into a framework of carrots—positive incentives, sticks—negative incentives, and sermons—discursive incentives, such a framework is only superficially insightful in elucidating how activist groups may have leverage over firms.

Table 13.1 Activist Group Tactics

Table 13.1 Activist Group Tactics

For this research-paper we distinguish four different mechanisms by which pressure may be leveraged upon firms. First, use can be made of the firm’s corporate governance system, for example, by buying shares and speaking at shareholder meetings. This mechanism is obviously restricted to in the case of publicly traded firms. Other mechanisms are more universally applicable. As firms generally have a profit motive, affecting operational costs and benefits is a second potentially effective mechanism.1 Costs and benefits can be affected in either of two forms: material and symbolic, that is through the marketplace (e.g., by convincing buyers to shop consciously or informing them through various labels about products and production processes) and through public opinion (e.g., via naming and shaming campaigns or trying to affect a firm’s reputation in mass media). In the case of publicly traded firms, the efficacy of both forms may be enhanced if they also have an effect on the firm’s stock price. A third mechanism is to engage with a firm more positively, respecting the firm as a party that is sufficiently trustworthy to conclude agreements. Social alliances, then, can be found of different sorts, for instance differing in the length of time of the engagement, ranging from short-term bargaining to long-term collaborative agreements. Finally, it may be decided by the activist group that setting up wholly novel and independent business systems to work with current firms is not seen as an option by the stakeholder group, for instance, on ideological grounds.2

Of course, in reality, these mechanisms do not always work independently. For example, discursive tactics may be needed to inform buyers and affect their attitude and evaluation of products or their providers. Likewise, the success of special labels, brands, and hallmarks in the market often crucially depends on a close collaboration between various parties, including firms, NGOs, academics, and even governments. And some of the new business ventures or systems can only thrive on the anticorporate rhetoric they espouse: fair trade is positioned opposite allegedly unfair regular trade. Next, we outline the four mechanisms in more detail.

Corporate Governance: SRI And Shareholder Financial Activism On Social Issues

Some activist groups make use of the principal-agent relationship between a firm’s shareholders and its management in order to leverage their claim (Waygood & Wehrmeyer, 2003). For privately held firms, they need to find allies among the firm’s shareholders, including institutional investors such as banks, insurance companies, pension funds, and social investment funds and issue their concerns through them. Leverage over the firm originates from the damage, in terms of reputation loss or higher cost of raising capital, resulting from divestment by the institutional investor. Socially responsible investment (SRI) “is an investment approach that uses both financial and nonfinancial criteria to determine which assets to purchase, but whose distinguishing characteristic is the latter” (Guay, Doh, & Sinclair, 2004, p. 126). According to Guay et al. (2004), its origins are in the 1920s, “when various religious groups stipulated that their investments not be used to support ‘sin’ shares (liquor, tobacco, gambling)” (p.126), but the monetary value of socially invested assets has increased steeply during the 1990s, when large institutional investors began to use their assets to pressure firms.

For publicly traded firms, activist groups have the additional option of using shareholder meetings as platforms for raising their issues. Such meetings receive routine attention from the financial mass media because of the publication of quarterly or annual profit statements and the discussion of major strategy changes. Therefore, they also lend themselves well for addressing nonfinancial issues by activist groups. It took several steps in the United States before this tactic was institutionalized (in the United Kingdom, see Waygood & Wehmeyer, 2003). A first important development occurred in 1942 when the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) ruled that “shareholders had the legal right to communicate to each other and to management through the medium of the company’s proxy material” (Marens, 2002, p. 370). Shortly thereafter the first attempts were made to use the shareholder proxy process for having a vote on social issues. Thus, during the 1940s, “questioning senior executives from the annual meeting floor was the occasional mode for raising social topics” (Proffitt & Spicer, 2006, p. 168).

Although such attempts did bring social issues to the attention of management, the proposals were usually rejected on the grounds of failing the “proper subject” test, which was formalized by the SEC to “exclude proposals designed to advance ‘general economic, political, racial, religious, social or similar causes'” (Proffitt & Spicer, 2006, p. 168). This situation changed in 1970, when a federal court decision forced the SEC to reinterpret its “proper grounds” clause. The occasion was “Campaign GM,” which succeeded to “force General Motors to include two socially oriented shareholder resolutions in the proxy statement mailed to the corporation’s 1.3 million owners,” but failed to gain support from GM’s large institutional investors (Hoffman, 1996, pp. 51-52).

Thus, a new tactic—the shareholder proxy voting process on social issues—was institutionalized. Once properly submitted and passing the proper grounds test, management has the option of either formulating a response to the proposal and submitting that response for a vote in the shareholder meeting or negotiating with the filers of a proposal on the conditions for their withdrawal of the proposal. Withdrawal then can be seen as an indicator of activist success, as management apparently has made sufficient concessions to satisfy the filers of the proposal (Graves, Rehbein, & Waddock, 2001; Proffitt & Spicer, 2006).

Apparently, there was a significant increase in the number of shareholder social resolutions around 1990, at least in the United States (Graves et al., 2001; Hoffman, 1996; Proffitt & Spicer, 2006). Hoffman argues that this may well have been the result of the founding of CERES,3 which was the first in the social investment movement to combine financial benefits for shareholders and the resolution of social issues in its objectives. Although the increased use of shareholder social resolutions might be considered an indicator for the success of these tactics, Vogel (1978, 2005), in his analyses of anticorporate activism, concludes that their impact on corporate policies largely consisted of marginal procedural adjustments, rather than ubstantial changes; its relevance was in stimulating a public political debate, and thereby facilitated subsequent government regulation. Graves et al. (2001) find evidence that the issues addressed in shareholder social activism vary over time and suggest that the waxing and waning of issues is at least partly related to fads and fashions in public interest in particular issues.

Operational Costs And Benefits

Although shareholder activism can work through raising costs for firms, such as costs of capital, its fundamental mechanism is not its impact on operational costs and benefits—but it is for a broad range of influence tactics. In this section we will outline two central routes of influence: directly through the marketplace and indirectly through public opinion.

Marketplace Tactics

To look at the operational costs and benefits associated with activism, studying political consumerism is a useful starting point (Holzer, 2006; Micheletti, 2003). Political consumerism concerns the choice of products, producers, and services on the basis of political values, virtues, and ethics rather than on material cost and benefits (Micheletti, 2003, p. ix-xi). Political consumerism can thus be seen as a politicizing of the customer, directed at leveraging some activist group’s claim, for its own benefit or for that of a third party whose cause is supported. Political consumers deploy their buying power to strive for social change.

Political consumerism can be exerted both negatively through boycotts (i.e., not shopping with banned sellers), and positively through buycotts (i.e., buying products and services from preferred sellers; Friedman, 1999). The efficacy of boycotts and buycotts is constrained by a problem of collective action, as the power behind political consumerism is “the power of agencies that command enough credibility to influence many people’s decisions and thus to transform individual choices into a collective statement” (Holzer, 2006, p. 407). Significant efforts are thus required to mobilize the crowds needed to substantiate the threat of using individual consumer power. This tactic therefore requires a large effort on the part of the activist group (Den Hond & De Bakker, 2007). As Vogel (2004) concludes, “It has proven very difficult to mobilize large numbers of consumers to avoid the products of particular companies for social or political reasons” (p. 96)

In spite of these difficulties, both boycotts and buycotts have a long tradition. The word boycott itself derives from the name of an English estate agent on an Irish estate who refused to grant tennants a reduction in their rents in a time of economic hardship and in turn was ostracized. Several historical overviews can be found showing how they were used already 125 years ago (Frank, 2003; Friedman, 1999). Early examples mainly concern local or regional orientations, for instance, regarding labor issues. Product labels were used to signal consumers that a certain product was made in unionized firms. Following the rise of corporations and their increased transnational nature, transnational consumer campaigns were also developed. Early examples thereof include the boycott of Nestlé during the 1970s and early 1980s for its marketing of instant formula in developing countries and the boycotts of Shell and other firms for their investments in South Africa during the apartheid regime. There are indications that the use of boycotts, boycotts, and labeling schemes has flourished since the 1990s (Micheletti, 2004). Nevertheless, their dependence on large numbers of participants makes them a costly tactic for activist groups.

The use of more violent tactics, such as blocking gates and other ways of obstructing production processes and daily routines, are less frequently applied but should be mentioned here. Apart from making newsworthy stories— and thereby potentially influencing public opinion—such tactics are aimed at increasing a firm’s operational costs. For example, one reason why animal rights groups liberate mink and other species that are kept for their furs is to financially ruin fur farms.

Public Opinion Tactics

Since the rise of mass media, attempting to inflict symbolic damage through public opinion tactics has become another option for activist groups (Friedman, 1999). Reputation has become an important asset for firms, especially for those operating in advertising-intensive consumer markets. Their market shares or their opportunities to attract and maintain a high-quality workforce in part depend on their reputation. Because of this, corporate reputation has become an interesting lever for activist groups to gain influence over firms.

Public opinion tactics can be seen as examples of “discursive” political consumerism, which is “expression of opinions about corporate policy and practice in communicative efforts directed at business, the public at large, and various political institutions” (Micheletti, 2004, p. 5). They can be contentious or noncontentious. Activist groups inflict symbolic damage if they succeed in convincing public opinion that the targeted firm does not comply with generally accepted or institutionalized rules, values, or categories. Conversely, they deliver symbolic gain by providing endorsements to firms that meet their standards.

One example of trying to inflict symbolic damage on firms is through “culture jamming,” which has its roots in the 1960s (Carducci, 2006; Rumbo, 2002). By taking corporate symbols and logos out of context and transforming them in public, protesters aim to disturb the firm’s image management and influence the mental associations consumers experience when viewing them in another instance. As Den Hond and De Bakker (2007) argue, the ambition of such a tactic is to convince the public at large, and through them political decision makers, that the targeted firm belongs to some morally disfavored taxonomic category. Doing so then could be a first step in creating public support for further activism, for example, for a boycott to succeed. After all, an important characteristic of culture jamming and related public opinion tactics is hidden in the fact that they do not require broad endorsements. As Bennett (2003) notes, “Unlike boycotts, many contemporary issue campaigns do not require consumer action at all; instead, the goal is to hold a corporate logo hostage in the media until shareholders or corporate managers regard the bad publicity as an independent threat to a carefully cultivated brand image” (p. 152). Thus, symbolic damage contains a threat of inflicting material damage.

Interestingly, King and Soule (forthcoming) evaluated the impact of protest on market value, including both marketplace and public opinion tactics. They found that the staging of protest did have a negative impact on stock price, but also that “the most powerful feature of protest vis-à-vis stock price lies in its ability to upset image management, not in its ability to threaten direct costs to firms” (p. 38).

Social Alliances

To activist groups, teaming up with a corporation to form a social alliance, or a cross-sector collaboration, is a third mechanism for exerting influence. There are indications that the number of cross-sector collaborations have significantly expanded through the 1990s (Rondinelli & London, 2003). Legitimizing the possibility of such alliances by emphasizing the potential mutual benefits to both firms and the causes that activist groups seek to promote is probably one of the conceptual breakthroughs of the report by Bruntland’s WCED (1987), but the idea had already been explored in the concept of “stakeholder management” (Freeman, 1984).

In one of the first analyses of social alliances, Westley and Vredenburg (1991) explored how Greenpeace (Canada) derailed Pollution Probe’s support for an “environmentally friendly” product line of a major Canadian grocery retailer. The case shows both a model for social alliances, as well as the tensions that such alliances and collaborations may evoke among the rank and file of activist groups. Shortly thereafter, in 1992-1993, Greenpeace (Germany) and Foron jointly developed a CFC-free refrigerator (Stafford, Polonsky, & Hartman, 2000). Yet, almost 2 decades of experience with social alliances has not resulted in any systematic research into their efficacy. Most academic analyses are based on case studies to the result that still “the rhetoric of partnership far exceeds its reputed efficacy” (Googins & Rochlin, 2000, p. 130).

Social alliances exist in many forms (cf. Hartman & Stafford, 1997; Rondinelli & London, 2003). Some forms include the transfer of money or employee time from the firm to the social partner (corporate philanthropy). In other forms, the objective is to change corporate policies and products. The latter forms include marketing agreements to differentiate products (certificating, licensing, branding), dialogue and training to improve corporate policies and procedures (knowledge transfer), and joint research and product development. Thus, social alliances are oriented toward stimulating alternatives, rather than toward pro-testing against the current order. They may nevertheless have far reaching consequences; they may, for example, change markets, policy schemes, and individual lifestyles (Schneidewind & Petersen, 1998).

Den Hond and De Bakker (2007) argue that in such situations activist groups can only be successful if they are able to convince the firm of the benefits of collaboration. Differences in language, culture, goal orientation, or values and ideologies may constrain either party to engage in collaborative engagements (Googins & Rochlin, 2000). Overcoming such differences is essential for collaboration to succeed, but may be easier for business firms than for activist groups. Whereas corporations need to accept that something can be learned from a nontraditional partner— the value of which can ultimately be expressed in increased profits or stock prices, and which thus favors a pragmatist approach to potential collaborations—activist groups need to internalize corporate interests in order to be able realize (part of) their objectives—but ideological or moral considerations may limit their preparedness to do so. For example, when collaborating, “corporations make it more difficult for [activist] groups to raise problems in other areas” (Holzer in press). Engaging with a profit-oriented partner may thus compromise support from their constituency or taint their reputation in the community of activist groups (Westley & Vredenburg, 1991).

New Business Systems: If You Cannot Change Them, Bypass Them!

Finally, if working with or against current firms is not seen as an option to achieve the activist groups’ objectives, a final mechanism of influence could be to step out of the dominant business systems. Creating alternative business systems provides the opportunity to establish new norms and standards that better fit the objectives of the activist group. For example, in the first half of the 19th century, the idea of a cooperative was explored. Since then, various sorts of workers’, consumers’, and producers’ cooperatives have been set up to counter corporate power in areas such as agriculture, finance, and retail resulting in, for instance, cooperative sugar refineries, banks, and supermarkets (Williams, 2007).

Today, activist groups may choose to develop alternative business systems to avoid the risk of cooptation or to demonstrate the viability of their alternative ideas. Bypassing the current economic system may be particularly attractive to radical activist groups, as they morally reject the practices of existing firms (Den Hond & De Bakker, 2007). It may imply a radical transformation in the ownership structure or the development of an alternative economic entity. One example is the development of local exchange trade schemes (LETS), which “operate as an alternative (local) market for the members’ goods and services” (Crowther, Greene, & Hosking, 2002, p. 355).4 Another example is in the many Fair Trade initiatives that have been developed since the 1940s.5 As Shreck (2005) notes, “The Fair Trade movement critiques the conventional agro-food system . . . through alternative trade channels that are more equitable than those typical of conventional trade network” (p. 17) Rejecting current practices and trying to overcome their constraints should result in more equal trading agreements. Although Fair Trade has become an umbrella term for a variety of initiatives and approaches, most of these initiatives demonstrate some characteristics of alternative business systems.

Another form of new business systems is found in social enterprises. These enterprises are organizations that link their activities to a social mission; they form a business-like contrast to traditional nonprofit organizations (Dart, 2004). A wide variety of examples can be found in the literature which range from labor cooperatives to neighborhood development projects (Borzaga & Defourny, 2001). In some of these enterprises, governments are heavily involved, whereas in others cooperation with existing firms is actively sought.

A subset of social enterprises is the community enterprises as they have developed in the United Kingdom. In a sense, community enterprises may be seen as being situated somewhere in between new business systems and partnerships, but with significantly stronger links to local communities. They are often aimed at the regeneration of local initiatives and involve the participation of key constituents in the management and governance of the enterprise (Tracey, Phillips, & Haugh, 2005). This position in these enterprises allows these constituents to exert significant influence.

Discussion

This section discusses our findings in two parts: first we highlight the efficacy of the different tactics used, and then we discuss whether the way in which activist groups deploy these tactics today is any different from earlier periods in time.

How About Efficacy?

So far we have discussed four mechanisms that constitute a broad set of methods through which activist groups try to influence corporate decision making. But how about their efficacy? Some caveats have to be made before we address this question. It should be noticed, first, that to date—grosso modo—systematic, comparative research is lacking. There is some anecdotal evidence but few systematic case studies, and there is ground for suspicion that research attention has predominantly focused on the more visible instances of activism vis-à-vis firms. Second, efficacy of activism is notoriously difficult to operationalize and measure (Giugni, 1998), as indicated by the discussion of using the withdrawal of a shareholder proxy voting resolution as an indicator of success—what precisely is the deal usually remains undisclosed. One reason for making operational and measuring the efficacy of activism is that it may well be moderated by context and depend on contingencies. It has, for example, been suggested that industry structure—the economic, organizational, and cultural features that function to enhance or constrain activist groups’ efforts to change industry behavior (Schurman, 2004)—is a relevant factor, but contingencies, such as changes in board membership or sudden rises or declines in profits, may also impart the efficacy of their efforts. Such opportunities may affect the working of different activist groups in different ways. Another reason is that multiple factors, among which activism is one, can be involved in producing social change. For example, activism against corporate involvement with apartheid in South Africa may not in itself have resulted in the abolishment of apartheid, nor given the final blow to the regime, but it has certainly been an important element in the overall movement (Seidman, 2003). Third, whereas some activist groups specialize in employing particular tactics—for example, some religious groups in filing shareholder resolutions—other activist groups, individually or in a joint and coordinated way, combine the use of various tactics in a particular campaign, and hence try to gain leverage through different influence mechanisms. Consequently, it will be difficult to relate the employment of particular tactics to their efficacy. Finally, efficacy is a concept that to some extent is difficult to match to the type of organizations and the type of actions we discussed in this research-paper, because the use of particular tactics may be more related to activist groups’ wish or need to confirm their social identity or express their ideology than to result in change (Rowley & Moldoveanu, 2003; Den Hond & De Bakker, 2007). For these reasons, the following discussion should be treated with caution.

One tentative conclusion, on the use of corporate governance as a mechanism for leveraging activists’ claims, is that in certain circumstances, business strategies have successfully changed, but that overall it is probably only having marginal effects (Waygood & Wehnmeyer, 2003). Regarding socially responsible investments, the value of portfolios has dramatically increased, but it remains a very small portion of overall invested assets (cf. Vogel, 2005). Regarding the cost and benefits mechanism, there is anecdotic evidence of instances of success and failure of particular protest events and campaigns. Beyond that, and in the absence of systematic evidence, there is perhaps the suggestion that public opinion tactics can be more effective than marketplace tactics. Sometimes, even the mere threat of activism suffices to influence firms, arguably even in situations where the threat is not made public.6

A similar evaluation could be made regarding social alliances: although we found very few instances of failed alliances, the lack of failures cannot be taken as a sign of efficacy but can perhaps better be considered as an indication of selection bias toward successful alliances, both in research and in activists’ and firms’ publicity, as neither party would want to be associated with failures. Finally, there is some paradox in the efficacy of new business systems. Although for some forms of new business systems— LETS, for example—survival may be the only meaningful indicator of success, for most other forms—cooperatives, fair trade initiatives, social enterprises, community enterprises—the realization of any social ambitions depends on their integration in regular economic life. Although fair trade is sometimes considered to make substantial impact because of its high growth rates (e.g., coffee and cocoa), Carducci (2006) notes that the share of the world market remains marginal. Similarly, Levi and Linton (2003) suggest that fair trade coffee campaigns have improved the lives of small-scale coffee farmers but serious barriers exist for expansion beyond the small niche of “ethical” coffee drinkers. Success of new business systems therefore might be fairly relative.

Few studies have tried to directly establish the efficacy of private politics. One recent exception is the King and Soule (forthcoming) study into the effects of protest on stock price. Another is Eesley and Lenox’s (2006) analysis of over 600 stakeholder group actions in the United States during 1971-2003. They find evidence that in general confrontational tactics such as boycotts, protests, and lawsuits are more effective than less confrontational tactics, such as letter-writing campaigns or proxy votes, as they impose costs on the targeted firm. But they also suggest that the choice of tactics can be restrained, and that tactics that appear to be less effective in general may work well for particular groups (Eesley & Lenox, 2006). Such studies are ambitious and groundbreaking and suggest that there is a need for a more systematic analysis (e.g., comparing different influence mechanisms, different periods of time, or the interplay between different forms of activism), but they must be done carefully to take into account the consequences of the combined or consecutive use of different tactics.

How Different Is the Present From the Past?

The second issue we want to discuss is whether today’s activism is really that different from earlier forms. Some authors argue that it is. One important element in their argument is the rise of the Internet and other digital communication networks. According to Bennett (2003), these technologies have been instrumental in the emergence of a new form of global activism characterized by a loose network structure and weak identity ties among its participants, but also by the ability to swiftly and continuously regroup and refigure itself around shifting issues, protest events, and political adversaries. Beyond reducing the costs of communication—between activist groups themselves and between them and their audiences—and of coordination over time and space, the Internet facilitates permanent campaigns, collaboration between parties who hardly know each other and share little social identity or ideology, and direct access to mass media for individual activists (Bennett, 2003). It is “the largest meeting place of all” (van Rooy, 2004, p. 16). Based on two case studies of activism, Coombs (1998) argues that the Internet is a potential equalizer of power difference between activist groups and firms, because it increases the density of the network ties around the targeted firm, increases the network centrality of the activist groups, and reduces the network centrality of the targeted firm (cf. Rowley, 1997). Thus, in comparison to the situation before the Internet became widely available, “the Internet can be a useful tool for changing the activist group’s standing in the organization’s stakeholder network. In turn, the power dynamic shifts making the activists and their concerns more salient to an organization” (Coombs, 1998, p. 299). The availability of the Internet has therefore enabled protest and to some extent been instrumental in changing power relations between firms and their stakeholders.

A second important element is the rise of globalization. Globalization can be defined as “the intensification of worldwide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa” (Giddens, 1991, p. 64). It has different aspects: cultural, economic, financial, political, environmental, and criminal, to name but a few. Economic globalization is argued to have been enhanced significantly by the political leaderships of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Since these days, there has been a greater reluctance of nation states to directly interfere in national and international market regimes. Nationally, much social and environmental regulation has been allegedly left to the market, for example, through the stimulation of industry self-regulation, corporate social responsibility, and conscious consumer choice. Internationally, there has been a significant rise in the clout of international trade regimes and multiparty agreements, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank, with a strong focus on free trade. Solutions to many problems were sought in the market.

Corporations have therefore not only been able to increase the geographical scale of their operations—as exemplified by increasingly international supply chains and market penetrations by Western multinational corporation—but also have experienced lessened political control over their national and international operations. Increasing numbers of corporations operate in multiple countries under different jurisdictions, thus allowing them to select favorable regulatory and competitive environments, potentially resulting in a race to the bottom. Many of them relocate or outsource production to low-wage countries (China, India, etc.), and

it is not uncommon practice to influence political decision making in order to create more favorable business conditions often at the expense of other stakeholders’ interests. In hyperbolical language, firms are taking over the world, filling in the void that retreating governments have left (Hertz, 2001).

Culturally—and in tandem with enhanced communication and information technologies—globalization has also resulted in a greater awareness of the “delusions of global capitalism” (Gray, 1998). Consequently, this has led to a broader focus of activist groups beyond the local and the national: they also want to change the frames that the public and decision makers use to make sense of global issues, change the specific policies and practices of global institutions, and support the reform of those institutions (van Rooy, 2004). This ambition for change pertains not only to international trade regimes and the underrepresentation of some interests therein, but also to the notion of the corporation. It has resulted in the invention of “alternative summits” hosted by networks of activist groups in parallel to “official” summits as organized by, for example, WTO and G7.7 A prominent example of this arguably new organizational form is the World Social Forum, initially organized in opposition to the yearly World Global Forum in Davos, Switzerland, but now having gained a life of its own.

Apparently, there was a change in context—globalization— and a new enabling, facilitating condition—the Internet—that in combination may account for the apparent shift in the intensity and nature of activism against firms. But of course things don’t change overnight; the rise of communication and information technologies as well as the advent of globalizations are developments that took place over decades. However, if a particular, relatively short period of time is to be pointed out, it could be argued that during the 1990s, a major shift took place in awareness of the relevance of these broader trends. And perhaps, the events around the WTO ministerial meetings in Seattle in November of 1999 could be seen as a culmination of these developments, because of the broad media coverage of the protests that brought to the fore the force of the antiglobalist movement’s arguments and its versatility in the use of the newly available technologies.

However, from another point of view, there clearly is continuity in how activist groups try to influence companies. For example, if the “Battle of Seattle” was a culmination point, its manifestation in Seattle builds on a long and strong local tradition of anticapitalist protest and mobilization (Levi & Olson, 2000). And if the “dot.cause” corporate watchdogs that appeared on the Internet because of the new communication and information technologies, it should be acknowledged that their activities build on a much longer tradition of critically monitoring corporate behavior by activist groups; the corporate campaign was “invented” during the 1960s by U.S. unions desperate for members (Manheim, 2001). Further, consumer boycotts were organized already a century ago (Friedman, 1999) and shareholder activism on social issues emerged a half a century ago (Marens, 2002). And although it could be argued that the rise of the Internet and other digital communication networks has made activist groups less dependent on traditional mass media, they still have to make use of traditional mass media, too. The Internet is a highly effective tool “to gather and spread information for those who not only have the technical facilities but also know what they are looking for” (Rucht, 2004, p. 30).

Conclusion

All in all, we would argue that since the 1990s, anticorporate activism may have developed a distinct flavor, drawing from an increasingly globalized context, and facilitated, perhaps even empowered, by new (networked) communication and information technologies. As corporations have expanded their geographical reach, but arguably are being less controlled or constrained in their activities, activists have started to look for tactics that could match these new conditions. For example, in a “boomerang effect” (Keck & Sikkink, 1998), local protests against poor labor conditions in the overseas—Third World—supply chains of major multinationals (Nike, the Gap, Starbucks, etc.), gained enormous leverage when Western groups started to campaign in Western markets to improving the working conditions of those employed in the overseas “sweatshops.”

However, when considering the mechanisms through with activist groups try to influence corporations, there appears to be considerable continuity. In cases such as Nike, shareholder resolutions are formulated, boycotts are organized, the firm’s reputation is tarnished, law suits are filed, and alternative sources of supply are being developed (e.g., Adbusters’ Blackspot sneaker).8 Although new forms of expression may have been found, the modern anticorporate campaign is built on mechanisms that have been in use for decades. The most recent mechanism appears to have been the least confrontational, the social alliance, legitimized and popularized in connotation with the concept of sustainable development.

References:

- Baron, D. P. (2003). Private politics. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 12(1), 31-66.

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 611-639.

- Bennett, W. L. (2003). Communicating global activism. Strengths and vulnerabilities of networked politics. Information, Communication & Society, 6(2), 143-168.

- Borzaga, C., & Defourny, J. (Eds.). (2001). The emergence of social enterprise. London: Routledge.

- Bowring, F. (1998). LETS: An eco-socialist initiative? New Left Review, 23(2), 91-111.

- Carducci, V. (2006). Culture jamming: A sociological perspective. Journal of Consumer Culture, 6(1), 116-138.

- Carmin, J., & Balser, D. B. (2002). Selecting repertoires of action in environmental movement organizations: An interpretive approach. Organization & Environment, 15(4), 365-388.

- Coombs, W. T. (1998). The Internet as potential equalizer: New leverage for confronting social irresponsibility. Public Relations Review, 24(3), 289-303.

- Crowther, D., Greene, A. M., & Hosking, D. M. (2002). Local economic trading schemes and their implications for marketing assumptions, concepts and practices. Management Decision, 40, 354-362.

- Dart, R. (2004). The legitimacy of social enterprise. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14(4), 411-124.

- Davis, K. (1960). Can business afford to ignore social responsibilities? California Management Review, 2(3), 70-76. De Bakker, F. G. A., & Den Hond, F. (in press). Introducing the politics of stakeholder influence: A review essay. Business & Society.

- Den Hond, F., & De Bakker, F. G. A. (2007). Ideologically motivated activism: How activist groups influence corporate social change activities. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 901-924.

- Eesley, C., & Lenox, M. J. (2006). Firm responses to secondary stakeholder action. Strategic Management Journal, 27, 765-781.

- Frank, D. (2003). Where are the workers in consumer-worker alliances? Class dynamics and the history of consumer-labor campaigns. Politics & Society, 31(3), 363-379.

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Marshfield, MA: Pitman. Friedman, M. (1999). Consumer boycotts: Effecting change through the marketplace and the media. London: Routledge.

- Frooman, J. (1999). Stakeholder influence strategies. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 191-205.

- Giddens, A. (1991). The consequences of modernity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Giugni, M. (1998). Was it worth the effort? The outcomes and consequences of social movements. Annual Review of Sociology, 371-393.

- Googins, B. K., & Rochlin, S. A. (2000). Creating the partnership society: Understanding the rhetoric and reality of cross-sectoral partnerships. Business and Society Review, 105(1), 127-144.

- Graves, S. B., Rehbein, K., & Waddock, S. A. (2001). Fad and fashion in shareholder activism: The landscape of shareholder resolutions, 1988-1998. Business and Society Review, 106(4), 293-314.

- Gray, J. (1998). False dawn: The delusions of global capitalism. London: Granta Books.

- Guay, T., Doh, J. P., & Sinclair, G. (2004). Non-governmental organizations, shareholder activism, and socially responsible investments: Ethical, strategic, and governance implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(1), 125-139.

- Hartman, C. L., & Stafford, E. R. (1997). Green alliances. Building new business with environmental groups. Long Range Planning, 30(2), 184-196.

- Hendry, J. R. (2006). Taking aim at business: What factors lead environmental non-governmental organizations to target particular firms? Business & Society, 45(1), 47-86.

- Hertz, N. (2001). The silent takeover. Global capitalism and the death of democracy. London: Heinemann.

- Hoffman, A. J. (1996). A strategic response to investor activism. Sloan Management Review, 37(2), 51-64.

- Holzer, B. (2006). Political consumerism between individual choice and collective action: Social movements, role mobilization and signaling. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(5), 405-415.

- Holzer, B. (in press). Turning stakeseekers into stakeholders: A political coalition perspective on the politics of stakeholder influence. Business & Society.

- Keck, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- King, B. G., & Soule, S. A. (in press). Social movements as extra-institutional entrepreneurs: The effect of protest on stock price returns. Administrative Science Quarterly.

- Levi, M., & Linton, A. (2003). Fair trade: A cup at a time? Politics & Society, 31(3), 407-432.

- Levi, M., & Olson, D. (2000). The battles in Seattle. Politics & Society, 28(3), 309-329.

- Manheim, J. B. (2001). The death of a thousand cuts. Corporate campaigns and the attack on the corporation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- March, J. G., & Olson, J. P. (1989). Rediscovering Institutions. New York: Free Press.

- Marens, R. (2002). Inventing corporate governance: The mid-century emergence of shareholder activism. Journal of Business and Management, 8(4), 365-389.

- McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117-127.

- Micheletti, M. (2003). Political virtue and shopping. Individuals, consumerism, and collective action. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Micheletti, M. (2004, April 13-18). Just clothes? Discursive political consumerism and political participation. Paper presented at the ECPR Joint Workshop Sessions, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Moe, T. M. (1981). A broader view of interest groups. Journal of Politics, 43, 531-543.

- Parker, A. R. (2003). Prospects for NGO collaboration with multinational enterprises. In J. P. Doh, & H. Teegen (Eds.), Globalization and NGOs: Transforming business, governments, and society (pp. 81-106). Westport, CT: Praeger Books.

- Proffitt, W. T., & Spicer, A. (2006). Shaping the shareholder activism agenda: Institutional investors and global social issues. Strategic Organization, 4(2), 165-190.

- Rehbein, K., Waddock, S., & Graves, S. B. (2004). Understanding shareholder activism: Which corporations are targeted? Business & Society, 43(3), 239-258.

- Rondinelli, D. A., & London, T. (2003). How corporations and environmental groups cooperate. Assessing cross-sector al-liances and collaborations. Academy of Management Executive, 17(1), 61-76.

- Rowley, T. J. (1997). Moving beyond dyadic ties: A network theory of stakeholder influences. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 887-910.

- Rowley, T. J., & Berman, S. (2000). A brand new brand of corporate social performance. Business & Society, 39(4), 397-H8.

- Rowley, T. J., & Moldoveanu, M. (2003). When will stakeholder groups act? An interest- and identity-based model of stake-holder group mobilization. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 204-219.

- Rucht, D. (2004). The quadruple ‘A’: Media strategies of protest movements since the 1960s. In W. van de Donk, B. D. Loader, P. G. Nihon, & D. Rucht (Eds.), Cyberprotest. New media, citizens and social movements (pp. 29-56). London: Routlege.

- Rumbo, J. D. (2002). Consumer resistance in a world of advertising clutter: The case of Adbusters. Psychology & Marketing, 19(2), 127-148.

- Schepers, D. H. (2006). The impact of NGO network conflict on the corporate social responsibility strategies of multinational corporations. Business & Society, 45(3), 282-299.

- Schneidewind, U., & Petersen, H. (1998). Changing the rules: business-NGO partnerships and structuration theory. In J. Bendell (Ed.), Terms for endearment (pp. 216-224). Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf.

- Scholte, J. A. (2004). Civil society and democratically accountable global governance. Government and Opposition, 39(2), 211-233.

- Schurman, R. (2004). Fighting “Frankenfoods”: Industry opportunity structures and the efficacy of the anti-biotech movement in Western Europe. Social Problems, 51(2), 243-268.

- Seidman, G. W. (2003). Monitoring multinationals: Lessons from the anti-apartheid era. Politics & Society, 31(3), 381-1-06.

- Shreck, A. (2005). Resistance, redistribution, and power in the Fair Trade banana initiative. Agriculture and Human Values, 22(1), 17-29.

- Stafford, E. R., Polonsky, M. J., & Hartman, C. L. (2000). Environmental NGO-business collaboration and strategic bridging: A case analysis of the Greenpeace-Foron alliance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 9, 122-135.

- Tracey, P., Phillips, N., & Haugh, H. (2005). Beyond philanthropy: Community enterprise as a basis for corporate citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics, 58, 327-344.

- van Rooy, A. (2004). The global legitimacy game: Civil society, globalization, and protest. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Vogel, D. (1978). Lobbying the corporation: Citizen challenges to business authority. New York: Basic Books.

- Vogel, D. (2004). Tracing the American roots of the political consumerism movement. In D. Stolle (Ed.), Politics, products, and markets: Exploring political consumerism past and present (pp.83-100). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Vogel, D. (2005). The market for virtue. The potential and limits of corporate social responsibility. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Waygood, S., & Wehrmeyer, W. (2003). A critical assessment of how non-governmental organizations use the capital market to achieve their aims: A UK study. Business Strategy and the Environment, 12(6), 372-385.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Westley, F., & Vredenburg, H. (1991). Strategic bridging: The collaboration between environmentalists and business in the marketing of green products. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(1), 65-90.

- Williams, R. C. (2007). The cooperative movement. Globalization from below. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.