This sample Organizational Memory Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Organization theorists, economists, and strategists have long sought to determine when organizations will be able to draw relevant information from their history. Although firms can sometimes learn from their experiences, we know that organizations and individuals frequently suffer from memory loss. Moreover, firms invest deeply in attempts to capture organizational memory in knowledge-management systems, but employees commonly underutilize these systems. As yet, our understandings on the performance benefits of organizational memory are still limited. These limited understandings likely stem from incomplete conceptualizations of information storage and retrieval and, in turn, from incomplete empirical tests.

Conceptualizations of information storage and retrieval explain the supply side and demand side of organizational memory. Supply-side conceptualizations describe the structure of organizational memory as information archives within an organization, including employees, ecology, structure, culture, and transformation processes. In addition, these conceptualizations also describe the structure of organizational memory in terms of external archives maintained by other organizations (e.g., news agencies, professional databases, tax agencies, and stock exchanges). These internal and external archival storages describe the existence of information in many places within and outside the organization. These storages constitute the distributed and overlapping structures of organizational memory.

One way to identify organizational memory is by its distributed structure. A distributed structure describes different information components that are stored in multiple locations within an organization (different pieces of information in different places). For instance, knowledge of how to weld metal exists in welding instruction manuals and in the heads of expert welders. Instruction manuals provide general information on how to weld, but expert welders have unique implementation skills that instruction manuals often do not capture.

Another way to identify organizational memory is by its overlapping structure. An overlapping structure describes the same information component that is stored in multiple locations within the organization (the same piece of information in different places). Continuing the welding example, general descriptive information about welding tools exists both in manuals and in the heads of experts (overlap between codified and noncodified information). In addition, welding instructions can appear in many books and on many Web sites (overlap of codified information).

In fact, organizational memory is often characterized by both a distributed structure and an overlapping structure. This dual characteristic makes it difficult to determine the effects of organizational memory on individual performance of organizational tasks. Doing so would require examining not only the supply side of organizational memory, but also the demand side of organizational memory.

Currently there exist few demand-side conceptualizations of organizational memory. Demand-side conceptualizations focus on information retrieval from particular storage sources. They differ from supply-side conceptualizations in two ways. First, demand-side conceptualizations can be less comprehensive because they focus on particular information storage bins or sources that individuals utilize to accomplish their tasks. In this way, demand-side conceptualizations can overlook important information sources not utilized by individuals. Second, demand-side conceptualizations can link individual performance of organizational tasks to information stored in organizational memory. As a result, demand-side conceptualizations can provide measures to assess the effects of organizational memory on individual performance of organizational tasks. Overall, demand-side conceptualizations of organizational memory are less comprehensive than supply-side conceptualizations, yet they provide important insights for information management.

This research-paper reviews supply-side and demand-side conceptualizations of organizational memory. It extends current conceptualizations by introducing two new organizational memory constructs. In addition, it uses measures from a new organizational memory construct to test hypotheses on how organizational memory can influence individual task performance. Finally, it provides discussions on empirical results and implications for management research and practice.

Supply-Side Conceptualizations Of Organizational Memory

Walsh and Ungson (1991) have defined organizational memory, in its most basic sense, as stored information from an organization’s history that can be brought to bear on present decisions. According to these organizational theorists, organizational memory consists of internal archives maintained within an organization (i.e., employees, ecology, structure, culture, and transformation processes) and external archives maintained by other organizations (e.g., news agencies, professional databases, tax agencies, and stock exchanges). This section describes supply-side conceptualizations of organizational memory as developed in the organizational theory literature.

Organizational Theory Literature

Studies in the organizational theory literature generally view organizational memory as storage bins or archives of information. These studies conceptualize how storage bins or archives of information can influence organizational performance. For example, in a study published by the Academy of Management Review in 1991, Walsh and Ung-son developed seven propositions on the potential impact of organizational memory on organizational decision-making processes. These propositions are quoted verbatim here:

Decisions that are critically considered in terms of an organization’s history as they bear on the present are likely to be more effective than those made in a historical vacuum.

Decision choices framed within the context of an organization’s history are less likely to meet with resistance than those not so framed.

Change efforts that fail to consider the inertial force of automatic retrieval processes are more likely to fail than those that do.

The automatic retrieval of past decision information that fails to meet the requirements of more novel situations is likely to promote deleterious decision making.

In inertial situations that call for routine solutions, the critical consideration of purposefully retrieved past decision information consumes a manger’s time and energy and, thus, creates wasteful opportunity costs.

The controlled retrieval of decision information that is not examined in the context of novel situations is likely to promote deleterious decision making.

The self-serving manipulation of organizational memory’s acquisition, retention, and retrieval processes by an organization’s members will enable their autocratic entrenchment and, thus, compromise the organization’s sustained viability.

Walsh and Ungson developed these propositions to illustrate the importance of organizational memory to firm performance. Other organizational theorists have also conceptualized the importance of organizational memory to firm performance. For example, Huber (2001) discussed organizational memory in the context of organizational learning, which is also essential for organizational performance.

In general, supply-side conceptualizations in the organizational theory literature tend to suggest the importance of organizational memory to firm performance. Nonetheless, there are shortcomings in these conceptualizations. They typically conclude that organizations can benefit from organizational memory but offer little guidance on how researchers can investigate these benefits in a systematic manner. Thus, a more comprehensive understanding of organizational memory requires a review of its supply-side conceptualizations.

Demand-Side Conceptualizations Of Organizational Memory

Currently, there exist few demand-side conceptualizations of organizational memory. Demand-side conceptualizations of organizational memory focus on how organizational memory can influence the performance of organizational members and their organizations. These conceptualizations tend to draw from studies in literature about psychology and the management of information system.

Psychology Literature

Studies in the psychology literature examine organizational memory at individual level (i.e., human memory). The human-memory literature demonstrates that individual recall of memory is imperfect. Many factors influence recall, including information availability, social desirability, and retention interval. Although such human memory studies provide important insights on imperfect human recall, they pay little attention to the benefits from access to memory and the interplay between personal memories and external memory aids such as other people or external representations.

Studies in social psychology and situated-cognition literature provide insights into the interplay between personal memories and external memory aids. External memory aids involving human interactions can enhance memory storage and recall. Other external memory aids involving external representations (i.e., not involving human interaction) can improve performance in problem-solving tasks. Nonetheless, it is not clear in these studies whether external memory aids that involve human interactions are more effective than those that do not involve human interactions.

Management of Information Systems Literature

Studies in the management of information systems literature commonly examine the use of particular computer systems designed to supplement an organization’s memory at the individual and group levels. These studies tend to focus on technology systems intended to replace human and paper-based memory systems. For example, Ackerman (1996) studied how information technology can support business processes (i.e., providing insights into how and where information might be of use within organizations). To gain these insights, Ackerman developed two approaches to organizational memory: (a) by studying how organizations use information technology to make recorded knowledge retrievable and (b) by studying how organizations use information technology to connect people with knowledge to those without knowledge.

Ackerman employed these two approaches in the Answer Garden project. The Answer Garden project combined elements of information databases and communication systems. Using the Answer Garden software, organizational members can retrieve information from organizational databases. Moreover, if the computer systems cannot provide organizational members with the desired information from existing databases, they will link these members to appropriate human experts who can personally address their questions.

Studies in the information systems literature, such as those conducted by Ackerman, generally provide important insights on how organizational memory can influence individual performance. Nonetheless, they provide limited understandings on how noncomputer users can benefit from decision information components of organizational memory stored outside of computer systems.

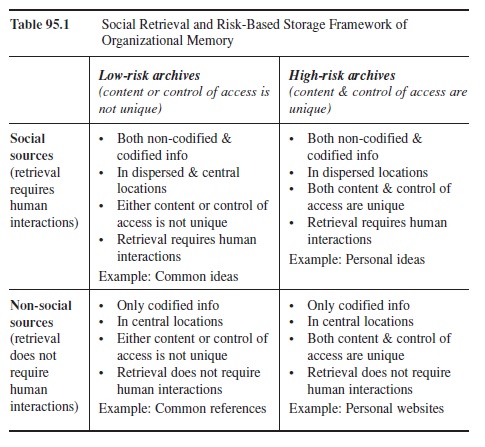

Extension Of Current Conceptualizations

Current conceptualizations provide limited understandings on the success or failure of using different sources of organizational memory. To extend these understandings, this research-paper introduces two new organizational memory constructs. The social retrieval construct extends demand-side conceptualizations and separates sources of information by whether human interaction is required during retrieval. The risk-based storage construct extends supply-side conceptualization and separates information by the probability of information loss when employees leave the organization. These constructs distinguish organizational memory by information sources (nonsocial and social sources) and probability of information loss (low-risk and high-risk archives).

Social Retrieval Construct

The social retrieval construct identifies organizational memory using two categories of information sources differentiated by the social interaction characteristics of information retrieval. These categories consist of nonsocial and social sources. Nonsocial sources consist of the self (information users) and other sources that do not involve people (nonhuman sources). Nonsocial sources provide information without requiring human interaction. Users can retrieve all types of information in their personal archives (the self), but only some types of information available in other archives (nonhuman sources). Users’ personal archives contain information that is either noncodified (in their heads) or codified (in their private offices). Other archives contain information that must be both codified and centralized in order for retrieval to occur without requiring human interaction (e.g., Web-based public lists of welding tools).

Social sources consist of other people providing information via human interaction. From social sources, users can retrieve all different types of information, including information that users cannot normally retrieve from non-social sources, such as noncodified information within human heads or codified information in private offices. For example, a colleague may have a particular list of welding tools that resides in his head and/or private office. To obtain this particular list, a user must interact with the colleague, even if the list contains explicit and codified information; as long as the information is in the source’s private possession, a user cannot obtain the information without the source’s permission.

Nonsocial and social sources are complementary categories separated by the human interaction requirement in information retrieval. They are not mutually exclusive sources of access to stored information. Most importantly, social sources offer access to all types of information in the organization, including information that is normally available from nonsocial sources. For example, a corporate intranet provides information that people can access from both nonsocial and social sources, because even a worker who lacks access to a computer (a nonsocial source) can ask a colleague (a social source) who does have intranet access to retrieve the information.

Risk-Based Storage Construct

Table 95.1 Social Retrieval and Risk-Based Storage Framework of Organizational Memory

Table 95.1 Social Retrieval and Risk-Based Storage Framework of Organizational Memory

The risk-based storage construct identifies organizational memory using two categories of information archives differentiated by the risk of information loss. They consist of low-risk archives and high-risk archives. These archives are differentiated by factors that influence the probability of information loss, particularly loss that occurs when knowledgeable people leave the organization.

Low-risk archives contain information that has a low probability of loss even if knowledgeable personnel leave the organization. Information is not likely to become lost after it has been codified and centralized (e.g., information stored in a knowledge management system by departed employees). Moreover, information is not likely to be lost when it is stored in multiple locations and forms. For example, it may be stored in hard copies, soft copies, or in people’s head. Combinations of these factors add to the complexity of information storage and retrieval—multiple people can have the same knowledge, which can be stored internally in people’s heads and externally in hard and soft copies.

High-risk archives contain information that has a high probability of loss when people leave the organization. Information is likely to be lost when it can be retrieved only by its own archivists, especially when it has a unique content and unique access by unique owners. For example, ideas in a leader’s head that have not been shared with other organizational members represent information with a high risk of loss because the information is unique and noncodified. Other information such as files in private offices can also face a high risk of loss because the information is unique and not centralized even though it is explicit and somewhat codified.

The risk-based storage construct accommodates the notion of external archives as a complementary memory source. Multiple individuals inside and outside the organization can retrieve information in external archives (e.g., news agencies and professional databases), which is less subject to loss following employee turnover. Table 95.1 describes the framework of organizational memory using the social retrieval and risk-based storage constructs.

Hypotheses On The Effects Of Organizational Memory On Individual Task Performance

In general, the use of organizational memory can either enhance or constrain performance. Relevant dimensions of performance include individual task success, team product development effectiveness, firm productivity, and innovation. This research-paper reviews the effects of stored information on individual task performance, using measures from the social retrieval construct of organizational memory. In particular, it introduces an empirical study examining the potential positive aspects of access to different organizational memory sources on individuals’ ability to solve business problems using decision information.

Assumptions About Task Environments

The effects of organizational memory can vary in different organizational task environments. This section describes three assumptions about different task environments in a typical organization.

First, information users in a typical organization will likely conduct multiple information processing tasks with multiple levels of complexity. For example, the same person can engage in both a complex task and a simple task (multitasking) within a short period (e.g., in the same day).

Second, information users will likely experience a high variance of emotions when working with other people (social sources) and low variance of emotions when working alone with manuals (nonsocial sources). Studies show that most human communications in American workplaces have to do with managing peoples’ emotions. Task environments where people work together can be characterized by more intense emotions such as excitement, enthusiasm, and happiness (high positive effect) and distress, nervousness, or fear (high negative effect). By contrast, task environments where people work alone can be characterized by less intense emotions such as drowsiness, sleepiness, and slug gushiness (low positive effect) and calmness, relaxation, and restfulness (low negative effect).

Third, information users will likely devote significant effort and time to developing and maintaining good relationships with human sources of information (high variance of emotions). By contrast, they do not have to develop or maintain good relationships with nonsocial sources of information (low variance of emotions).

Data Collection in a Simulated Task Environment

An empirical study was conducted in a controlled experiment over a continuous 11-hour period. The study involved nearly 200 business students in the same cohort solving 120 problems related to business plan evaluation. In the study, a task environment was simulated to meet the assumptions discussed in the previous section. Nonsocial sources were manipulated in the form of reference manuals users. Social sources were manipulated in the form of team members who have received training in specific areas needed for the tasks. Personal knowledge was measured by multiple-choice tests on conceptual understanding of the tasks.

Controlling for human efforts, task performance was expected to vary by two factors: a person’s knowledge about the task and the external environment where he or she can retrieve the information needed to perform the task. With respect to the first factor, a person’s requisite knowledge was measured before he or she started the task. For example, the task required a person to determine the financial performance of a company using internal rate of return measures (the IRR formula). The requisite knowledge of this task was the IRR formula. Two scenarios related to personal knowledge were considered in this context: (a) the person has the necessary personal knowledge (the IRR formula) to accomplish the task and (b) the person does not have the necessary personal knowledge to accomplish the task. Moreover, there were four scenarios related to external sources of information: (a) the person does not have access to any external sources, (b) the person has access to social sources, (c) the person has access to nonsocial sources, and (d) the person has access to both social and nonsocial sources.

Let us consider a particular case in which the person does not know the IRR formula. In this case, he or she faces multiple choices. First, the person can skip the problem. Second, he or she can guess the solution. Third, he or she can consult a financial accounting handbook (a nonsocial source) for the formula before attempting to solve the problem. Fourth, the person can go to a financial accountant (a social source) to ask for the formula or even the solution itself. Moreover, the person can also do a combination of these activities.

Empirical Tests

This research-paper describes an empirical study modeled after the previous example. The study draws on supply-side and demand-side conceptualizations of organizational memory.

It develops and tests three hypotheses on how well an individual can accomplish organizational tasks conditioned on whether he or she has personal knowledge, access to social sources of information, and/or access to nonsocial sources of information.

Hypothesis 1

The first hypothesis focuses on information users without personal knowledge but with access to either social or nonsocial sources. It predicts an information user without personal knowledge but with access to social sources will perform better than another user with access to nonsocial sources.

Motivations for this hypothesis are drawn from studies in psychology, management of information systems, and organizational learning literature. There are three key arguments. First, information users tend to prefer social sources to nonsocial sources. Second, information users tend to utilize social sources more extensively than nonsocial sources. Third, information users can obtain from social sources both the needed information and the help to process the needed information; by contrast, information users can obtain from nonsocial sources only the needed information, but not help in processing the needed information (when nonsocial sources do not employ computer technology). Following these arguments, it has been hypothesized that without personal knowledge, the effect of access to social sources alone on task performance is greater than the effect of access to nonsocial sources alone (Hypothesis 1).

Hypothesis 2

The second hypothesis focuses on information users without personal knowledge and access to both social and nonsocial sources. In this case, both social and nonsocial sources provide the same needed information that is not available from personal knowledge. The prediction follows Hypothesis 1 by suggesting a less knowledgeable information user with access to social sources will perform better than another user with access to nonsocial sources. However, it extends Hypothesis 1 by suggesting that an in-formation user without personal knowledge will gain fewer additional benefits from nonsocial sources when he or she has access to social sources.

Motivations for this hypothesis flow from a hypothetical question of what happens when an information user does not have personal knowledge but has access to both social and nonsocial sources of information. The basic argument is if the person does not know how to begin solving a problem, he or she should rely on an expert (a social source) who can provide instructions and possibly the actual solution. Moreover, the person should not rely on a manual (a nonsocial source) that can only provide instructions on how to solve a problem, especially when he or she does not know how to follow those instructions.

Conceptually, within a typical organization, information users cannot process all information available from both social and nonsocial sources because they have limited information processing capabilities. Often they have to choose between multiple sources. Their choices will likely reflect different tradeoffs associated with social and non-social sources.

Information users without personal knowledge will likely identify the trade-offs associated with social sources by their high-cost/high-benefit structure. The costs of gaining access to social sources can be high for all information users because they have to invest in maintaining relationship with people as their sources of information. These costs can be emotions and time. However, the benefits of social sources can be especially high for information users without personal knowledge because, as discussed, they will likely benefit from working with people who can provide not only the information for the task, but also possibly the task solution. (This saves them from having to complete information processing activities.)

Information users without personal knowledge will likely identify the trade-offs associated with nonsocial sources by their low-cost/low-benefit structure. The costs of gaining access to nonsocial sources can be low for all information users because they do not have to maintain relationships with people when working alone. However, the benefits of nonsocial sources can also be low because they do not generally provide additional information processing capabilities (when they do not involve computer technology).

Without personal knowledge, information users can benefit from both social and nonsocial sources. Economically, social sources can trump nonsocial sources for those without personal knowledge. The reason is that social sources can provide both the needed information and the ability to process the needed information, whereas nonsocial sources can provide only the needed information. Psychologically, social sources can also trump nonsocial sources for those without personal knowledge. Based on studies of human preference for different sources of information, information users will likely ignore nonsocial sources when social sources are equally available. Following these arguments, it has been hypothesized that without personal knowledge, the effect of access to nonsocial sources reduces with access to social sources (Hypothesis 2).

Hypothesis 3

The third hypothesis focuses on information users with personal knowledge and access to both social and nonsocial sources. In other words, information overlaps from three sources: personal knowledge, social sources, and nonsocial sources. Hypothesis 3 extends the arguments developed in Hypothesis 2. In particular, Hypothesis 2 suggests information users without personal knowledge will gain less additional benefits from nonsocial sources when they have access to social sources. Hypothesis 3 extends

Hypothesis 2 by suggesting that information users with personal knowledge will gain fewer additional benefits from social sources than from nonsocial sources when both sources provide the same needed information.

The main motivation for Hypothesis 3 has to do with information-processing capabilities. When information users have personal knowledge about the task, they will likely have the necessary information-processing capabilities to accomplish the task. They are different from information users who do not have personal knowledge about the task. Hence, they will likely experience a different set of tradeoffs when it comes to information choices between social sources and nonsocial sources.

Information users with personal knowledge will likely identify the trade-offs associated with social sources by their high-cost/low-benefit structure. For reasons already discussed, the costs of social sources are universally high for all information users regardless of their knowledge level. However, the benefits of social sources for knowledgeable users can be low, because they may not need the additional information processing capabilities that are uniquely associated with social sources.

Information users without personal knowledge will likely identify the trade-offs associated with nonsocial sources by their low-cost/high-benefit structure. Following the previous discussion, the costs of nonsocial sources are universally low for all information users regardless of their knowledge level. Nonetheless, the benefits of nonsocial sources for knowledgeable users can be high, because they already have the ability to process information and can quickly arrive at a solution provided additional information about the task is known.

With personal knowledge, information users cannot cumulatively benefit from both social and nonsocial sources. Economically, nonsocial sources can trump social sources for those with personal knowledge who do not necessarily benefit from social sources more than from nonso-cial sources. With social sources having a high-cost structure and nonsocial sources having a low-cost structure, knowledgeable users are better off working with nonsocial sources. Following these arguments, personal knowledge has been hypothesized to interact with social sources and nonsocial sources; hence, with personal knowledge, the effect of access to social sources alone on task performance reduces more than the effect of access to nonsocial sources alone (Hypothesis 3).

Boundary Conditions

These three hypotheses provide insights on the interactions between personal knowledge, social sources, and nonsocial sources and their joint influences on individual task performance. At the same time, they also highlight three important boundary conditions. First, the predictions apply to cases in which information users face time constraints in performing organizational tasks. Second, social sources are substitutes, not complements, for nonsocial sources. Third, recent advances in computer technology might allow non-social sources to mimic social sources in cueing users to retrieve and process information effectively. Such technology sometimes offers better ease of search than via social sources. For example, computer search engines can help bring information from dispersed locations to the users’ desktop with minimal user effort. Some technology enables categorical and full-text search that can potentially make nonsocial sources more efficient than social sources. Hence, it is possible that nonsocial sources employing computer technology can provide additional information processing capabilities similar to those provided by social sources. This research-paper reports a study that empirically investigates cases in which nonsocial sources do not employ computer technology.

Empirical Tests

These hypotheses were tested in controlled experimental settings. As expected, the results on the effects of personal knowledge follow basic intuition. Information users with personal knowledge are twice as likely as users without personal knowledge to arrive at the right task solutions. Note that information users without personal knowledge can skip the task or guess at the solution. Other results provide support for all three hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 suggests that without personal knowledge, the effect of access to social sources on task performance is greater than the effect of access to nonsocial sources. Two important results arise from tests of Hypothesis 1. First, information users without personal knowledge but with access to social sources are three times more likely to arrive at the right task solution than users without personal knowledge or access to any external source of information. In other words, knowing people who know triples the odds of arriving at the right solution. Second, information users without personal knowledge but with access to nonsocial sources are 34% more likely to arrive at the right task solution than users without personal knowledge or access to any external source of information. In other words, having relevant manuals improves the odds by 34%.

As reported, with personal knowledge, task performance improves by 100%. Without personal knowledge, task performance improves by 200% with social sources and 34% with nonsocial sources. However, the benefits are not cumulative. Hypothesis 2 suggests that information users without personal knowledge do not benefit cumulatively from having access to both social sources and nonsocial sources. In particular, the effect of access to nonsocial sources on task performance is expected to reduce with access to social sources. Results show that information users without personal knowledge but with access to both social and nonsocial sources do not benefit cumulatively from having more information. In fact, their aggregate task performance benefits reduce by 24% when they have access to all three sources of information: personal knowledge, nonsocial sources, and social sources.

Hypothesis 3 extends Hypothesis 2 by suggesting that with personal knowledge, the effect of access to social sources reduces more than the effect of access to nonsocial sources. As in Hypothesis 2, results show information users do not benefit cumulatively from having access to both social and nonsocial sources. For information users with personal knowledge, the aggregate task performance benefits of having access to both personal knowledge and social sources reduce 40%. By contrast, the aggregate task performance benefits of having access to both personal knowledge and nonsocial sources reduce by only about 19%.

Discussion

This research-paper has two main objectives. The first has to do with the development of the social retrieval and risk-based storage constructs of organizational memory. The second has to do with the effects of organizational memory on individual task performance.

Results from this analysis confirm basic insights about organizational memory and extend these insights into new arenas. First and perhaps most intuitively, better task performance arises from both greater personal knowledge and access to external memory aids via social sources and nonsocial sources. Second, social sources and nonsocial sources have substantially different effect sizes: having access to people who likely have relevant information in their personal possession is more effective than having access to manuals with the relevant information. Third, in the absence of personal knowledge, users do not utilize all information available from social and nonsocial sources: The aggregate task performance benefits from access to both sources are less than the sum of the benefits from access to discrete social and nonsocial sources. Fourth, given a decline in aggregate task performance benefits, the benefits from access to social sources decline less than the benefits from access to nonsocial sources when users have access to both sources (i.e., results of the study present an extreme case of users ignoring nonsocial sources completely). Fifth, task performance benefits from access to personal knowledge decline with access to both social and nonsocial sources of knowledge. For example, people must have some personal knowledge in order to benefit from having manuals; however, they must not have some personal knowledge in order to benefit from having access to other people.

These results shed light on issues described in the introduction: (a) organizations and individuals within organizations can learn from their past, yet they frequently suffer from memory loss, and (b) firms invest in knowledge management systems, yet employees tend to underutilize them.

Concerning the first, this conceptual framework identifies occasions of memory loss within the firm—when employees who have unique control of unique information leave the firm. It specifies the probability of memory loss linked to employee turnover—only information in the high risk archives is likely to be lost when employees leave the firm; other information in the low-risk archives, retrievable from both social and nonsocial sources, is not likely to be lost when employees leave the firm. However, given the strong preference for social sources, the loss of a social contact can be very important. Moreover, even if the information could be accessed from nonsocial means, it may not be—especially when there is a lack of personal knowledge necessary to extract the benefits from access to information available via nonsocial sources.

Concerning the second, empirical tests demonstrate returns on firms’ investment in nonsocial sources of information (reference manuals improved task performance by 34%). Although we expect a greater improvement with knowledge management systems, the results with reference manuals can explain why firms continue to invest in non-social sources even when studies show that employees tend to underutilize them—because users benefit from nonsocial sources (34% more than when they have no access to any external memory aid).

These results also explain a follow-up question—why do employees underutilize nonsocial sources when they can benefit from them? In normal organizational settings, users often have options between social and nonsocial sources of information within the organization. On the one hand, nonsocial sources generate a 34% improvement in performance benefits when compared to having no access to any external memory aid. On the other hand, nonsocial sources generate a 77% reduction in performance benefits when compared to having access to people who likely have the relevant information. These findings have implications for researchers and managers.

Implications for Researchers

By extension, this analysis has implications for explaining two ambiguous empirical findings on the effects of employee turnover and firms’ investment in knowledge management systems in existing literature. The first ambiguity is that studies in literature are not clear on the effects of employee turnover; some studies show firms are negatively affected by employee turnover, whereas other studies show firms are not affected. This ambiguity can be explained by looking at the supply side and the demand side of organizational memory.

From the supply side, employee turnover does not necessarily equate with a loss of access to information—firms only lose unique information in control of unique employees who leave the firm (high-risk archives). Hence, the effect of employee turnover on performance can potentially be moderated by whether the relevant information held by departing employees exists in the high-risk or low-risk archives. A negative effect is expected if the information exists only in the high-risk archives. No effect is expected if the information exists in the low-risk archives or is readily available in the external archives. For example, a departure of a highly skilled specialist hurts the operation of the firm only if his skills are so unique that the firm cannot replace him with another person internally (low-risk archives) or externally (external archives). Nonetheless, if the person is a key node in a social network, and thus a way of getting to the information that is held in external archives or with another employee, the loss may be important.

From the demand side, users prefer and benefit from social sources more than from nonsocial sources; hence, employee turnover may cause the remaining employees to believe that their performance will suffer. Thus, researchers’ choices of performance measures are expected to moderate the effect of employee turnover. In particular, subjective measures of task performance can be associated with a negative effect of employee turnover, whereas objective measures can be associated with other effects driven primarily by supply-side factors as previously discussed.

The second ambiguity is that the literature is not clear on the performance impact of firms’ investments in knowledge management systems. In particular, it is not clear why firms continue to make these investments even when it has been shown that employees tend to underutilize these resources. Again, this ambiguity can be explained by looking at the supply side and demand side of organizational memory. From the supply side, information stored in knowledge management systems is not likely to be lost when employees leave the firm (low-risk archives). From the demand side, access to nonsocial sources has greater benefits for task performance than no access.

Implications for Managers

These results are unlikely to surprise some users of organizational memory, because studies show people commonly prefer social sources to nonsocial sources of information. However, they are highly relevant for shaping incentives to invest in different retrieval mechanisms. Two important questions arise concerning the trade-offs associated with investments in social sources and nonsocial sources. First, social sources are more susceptible to loss due to employee turnover, but they are also more effective than nonsocial sources—what can managers do to reduce the risk of memory loss associated with social sources? Second, nonsocial sources are less susceptible to loss due to employee turnover, but they are also less effective than social sources—what can managers do to improve the performance impact of non-social sources? The following are some potential answers to these questions.

The first challenge for managers is to reduce the risk of memory loss associated with the social sources of organizational memory. Managers can do this with supply-side and demand-side solutions. The supply-side solution involves investments in knowledge management systems, effectively making information available from people (social sources) and from computers (nonsocial sources). The demand-side solution involves information sharing among employees, effectively turning unique information available from unique employees (high-risk archives) into shared information available from multiple employees (low-risk archives).

In practice, the supply-side solution—investing in the nonsocial sources—has been a common approach; firms have invested millions of dollars to capture organizational memory in knowledge management systems. Nonetheless, employees tend to underutilize these resources. This brings us to the demand-side solution, which we believe has been underemphasized. The risk of memory loss due to employee turnover associated with social sources may well outweigh the benefits.

This study provides information about the relative benefits from access to social and nonsocial sources of organizational memory. It identifies ways to reduce the risk of memory loss associated with social sources in that non-codified and dispersed information that exists in multiple locations is not highly susceptible to loss during employee turnover. (Table 95.1 describes the framework of organizational memory.) Specifically, it suggests that managers can benefit from investing in low-risk archives that make up social sources. They can do this through a system of apprenticeship or in discussion groups, in which organizational members share information without having to undertake codification and centralization.

The second challenge for managers is to improve the performance impact of nonsocial sources to rival that of social sources. Managers can do this by acquiring advanced technology to augment the performance impact of nonso-cial sources at two levels. At the macro level, technology provides categorical search by bringing information from dispersed locations to the users. For example, computer databases such as ProQuest can bring required articles to users’ desktops. However, users still have to read them to find relevant information. At the micro level, technology provides full-text search by facilitating information processing and enabling users to sieve through available information more effectively. For example, computer search engines such as Google Desktop, Microsoft’s “find,” and Acrobat’s “search” can help users to conduct micro searches of keywords within documents.

Limitations

The study introduced in this research-paper manipulated nonsocial sources in the form of reference manuals that are readily available to the users. This approach neglects the use of technology which can potentially improve the performance impact of nonsocial sources. Specifically, users of nonsocial sources can benefit from technology that simulates an interactive cueing process similar to that occurring among social sources of information. This cueing process can mimic social sources in providing solutions with appropriate inputs. The extent of this improvement—whether nonsocial sources can rival that of social sources in performance impact—remains open for future investigations.

Future Research Directions

These findings generate a number of questions for future research. First, it would be useful to examine negative aspects of organizational memory, such as the potential for trapping organizations in suboptimal past activities.

Second, organizations have different incentive structures for users and sources. Some firms reward users and sources equally, whereas other firms do not. Future investigations are needed to advance understanding on whether social sources will generate greater benefits than nonsocial sources if users and sources do not share similar goals and incentives.

Third, it is not clear when the use of computer technology might augment the performance benefits from access to nonsocial sources to the point that they would rival the benefits from access to social sources. With increasingly advanced search technology, the benefits from access to nonsocial sources through use of a computer will likely be greater than those without; nonetheless, the tacit and organizationally embedded nature of much relevant knowledge suggests that social sources will continue to be highly relevant sources of organizational memory.

Conclusion

This research conceptualizes organizational memory as information stored in high-risk and low-risk archives within the organization that people can retrieve from social and/or nonsocial sources when they need to make current decisions. It provides insights into the task performance benefits of organizational memory by examining the direct and interactive effects of access to personal knowledge, social sources, and nonsocial sources of information. The analyses of task performance benefits of organizational memory extend understandings beyond conventional wisdom, such as “the smarter you are, the better you do.” Most importantly, the findings provide explanations for several firm activities that have puzzled researchers and managers.

Overall, this research-paper provides evidence to support normal firm practice of hiring the most qualified employees as well as controversial firm practices such as investing in knowledge management systems and discounting environmental factors characterized by transactive measures of specialization, credibility, and coordination. Firm practice of hiring the most qualified employees is a way of using personal knowledge to facilitate task performance. This research shows personal knowledge is the biggest determinant of task performance. At the same time, this research also recognizes that jobs can change over time, and employees’ personal knowledge may not always be available. These factors give rise to controversial firm practices.

Firm practice of investing in knowledge management systems is a way of using nonsocial sources to facilitate task performance. This research shows nonsocial sources can improve the task performance of employees who have personal knowledge more than employees who lack personal knowledge. It suggests that firms get a good return for their investments in knowledge management systems when they hire knowledgeable employees and when these systems support routine tasks (i.e., employees usually know how to process these tasks). The problem, however, concerns nonroutine tasks (i.e., employees face the challenge of figuring out how to process these tasks, which are beyond their existing knowledge). This research shows the effects of personal knowledge and social sources increase when tasks become more complex. These results suggest a challenge for firms to maintain a balance between investing in nonsocial and social sources in support of different types of tasks within their organizations.

References:

- Ackerman, M. S. (1996). Definitional and contextual issues in organizational and group memories. Information Technology & People, 9(1), 10-24.

- Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. (1999). Knowledge management systems: Issues, challenges, and benefits. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 1(7), 1-36.

- Anand, V., Manz, C. C., & Glick, W. H. (1998). An organizational memory approach to information management. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 796-809.

- Argote, L. (1999). Organisational learning: Creating, retaining, and transferring knowledge. Norwell, MA: Kluwer.

- Argote, L., & Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: A basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 150.

- Baddeley, A. D. (1998). Human memory: Theory and practice (Rev. ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation [Special issue]. Organization Science, 2(1), 40-57.

- Bystrom, K. (2002). Information and information sources in tasks of varying complexity. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 53(7), 581-591.

- Bystrom, K., & Hansen, P. (2005). Conceptual framework for tasks in information studies. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 56(10), 1050-1061.

- Bystrom, K., & Järvelin, K. (1995). Task complexity affects information seeking and use. Information Processing & Management, 31(2), 191-213.

- Campbell, D. T. (1988). Task complexity: A review and analysis. Academy of Management Review, 13(1), 40-52.

- Dennis, A. R. (1996). Information exchange and use in group decision making: You can lead a group to information, but you can’t make it think. MIS Quarterly, 20(4), 433-157.

- Galbraith, J. R. (1977). Organization design. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Gladstein, D. L. (1984). Groups in context: A model of task group effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29(4), 499-517.

- Huber, G. P. (1991). Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures [Special issue]. Organization Science, 2(1), 88-115.

- Huber, G. P. (2001). Transfer of knowledge in knowledge management systems: Unexplored issues and suggested studies. European Journal of Information Systems, 10(2), 72-79.

- Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383-397.

- Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1996). What firms do? Coordination, identity, and learning. Organization Science, 7(5), 502-518.

- March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. New York: Wiley.

- Markus, L., & Keil, M. (1994). If we build it, they will come: Designing information systems that people want to use. Sloan Management Review, 35(4), 11-25.

- McGrath, J. E., & Argote, L. (2001). Group processes in organizational contexts. In M. A. Hogg & R. S. Tindale (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Group processes (Vol. 3). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- McGrath, J. E., Arrow, H., & Berdahl, J. L. (2000). The study of groups: Past, present, and future. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(1), 95-105.

- Moreland, R. L., & Myaskovsky, L. (2000). Exploring the performance benefits of group training: Transactive memory or improved communication? Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 117-133.

- Olivera, F. (2000). Memory systems in organizations: An empirical investigation of mechanisms for knowledge collection, storage and access. Journal of Management Studies, 37(6), 811.

- Simon, H. A. (1990). Invariants of human behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 41(1), 1-19.

- Simon, H. A. (1991). Bounded rationality and organizational learning [Special issue]. Organization Science, 2(1), 125-134.

- Stein, E. W. (1995). Organizational memory: Review of concepts and recommendations for management. International Journal of Information Management, 15(1), 17.

- Walsh, J. P. (1995). Managerial and organizational cognition: Notes from a trip down memory lane. Organization Science, 6(3), 280-321.

- Walsh, J. P., & Ungson, G. R. (1991). Organizational memory. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 57.

- Wegner, D. M. (1987). Transactive memory: A contemporary analysis of the group mind. In B. Mullen & G. R. Goethals (Eds.), Theories of group behavior (pp. 185-208). New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Wegner, D. M., Erber, R., & Raymond, P. (1991). Transactive memory in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(6), 923-929.

- Wegner, D. M., Giuliano, T., & Hertel, P. T. (1985). Cognitive interdependence in close relationships. In W. J. Ickes (Ed.), Compatible and incompatible relationships (pp. 253-276). New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Zander, U., & Kogut, B. (1995). Knowledge and the speed of the transfer and imitation of organizational capabilities: An empirical test. Organization Science, 6(1), 76-92.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.