This sample The Global Manager’s Work Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Within the time frame of a single generation, the traditional boundaries for management have been dissolved and replaced by an integrated, interconnected global economy. Pick up any newspaper, scan the recent business publications in your local bookstore, or surf the Web and you are certain to encounter the word “global.” Not since the time that nations industrialized their economies have we encountered such powerful economic forces as those presently brought by the marriage of information technology and globalization. Succeeding in the global economy has risen to the top of many organizational agendas, and in increasing numbers, it is global leaders who are asked to lead the way.

Unfortunately, these transformations have occurred at such a pace that we have had little time in the organizational field to gain consensus as to what globalization and its consequences mean for management. Currently, the global management and leadership literature lacks theoretical ground, and there are multiple competing frames of reference. While it is beyond the scope of this research-paper to create consensus around this topic, this research-paper does seek to outline and frame the key contextual issues, concepts, and current directions that inform the research and practice of global management in the 21st century.

Simply put, global management is defined by its context. This context is one in which global organizations operate across national borders, simultaneously achieving the twin aims of global integration and local differentiation. This environment is understood in the field to be both quantitatively and qualitatively more complex than the one in which more traditional (and researched) types of leadership take place. In navigating this complexity, global management can be defined as leadership processes enacted across interacting boundaries of distance, country, and culture. The opening section of this research-paper seeks to embed global management within its context.

The next section identifies some of the key concepts in the study of global management. At present, the literature remains largely at a conceptual stage. Fortunately, however, a core set of ideas serves as touchstones. The global management concepts that will be discussed in this section include (a) culture shock, (b) global mind-set, (c) cultural adaptability, (d) cross-cultural values, (e) cultural intelligence, (f) learning to learn, and (g) global leader competencies.

The final two sections of this research-paper explore current and future directions in global management for research and practice, respectively. In terms of research, a number of established theories and models can be applied to investigations of global management. Those covered in this research-paper include (a) behavioral complexity, (b) social identity theory, (c) boundary role theory, (d) connected/relational leadership, (e) and corporate social responsibility. Linking global management to existing theories such as these is critical for new papers and knowledge in this area to progress. Finally, from an applied perspective, new knowledge can also be gained by linking global management to key organizational issues. This research-paper concludes by exploring issues of global management in light of the following: (a) selection, (b) performance appraisal, (c) talent management, (d) leadership development, and (e) organizational culture.

As the breadth and depth of globalization expands, we are advancing toward a time in which all leadership will become global in scope. Thus, research and inquiry into this topic will remain timely and relevant throughout the 21st century. Let us now discuss the complex context in which global management takes place.

Context: Understanding And Defining Global Management

There is a growing sense that events occurring throughout the world are converging rapidly to shape a single, integrated world where economic, social, cultural, technological, business, and other influences cross traditional borders and boundaries such as nations, national cultures, time, space, and industries with increasing ease. —Barbara Parker

Reports in the academic and popular press make it clear that organizational life, as well as life apart from organizations, transpires in deference to an increasingly global and interconnected world. Most would surely agree that the changes brought forth by globalization have a significant impact on leadership and managerial processes. The removal of boundaries and increasing connections create both challenges and opportunities for leadership. In this section, we explore the context of global management beginning with its origins.

Origins of Global Management

Prior to the mid-1980s, “global management” was not a commonly used term. Up until this time, the leadership context was not global in scope but rather focused on “international,” “cross-cultural,” or “expatriate” issues. Much of this research was conducted on noncorporate populations including samples of Peace Corps workers, international diplomats, missionaries, and the military. A common thread in this early research was the identification of various challenges these groups experienced in working effectively in other cultures. For example, the challenge for the Peace Corps volunteer is to relocate and adjust to living in another culture while assuming the role of teacher and helper. The role of the international diplomat is to relocate and adjust to living and working in another culture in order to represent the interests of the diplomat’s country at a high level of political sensitivity. The role of the military spouse may be to relocate and adjust to living in an enclave of fellow expatriates. A central concept emerging from this early research is the notion of culture shock. Culture shock, defined in terms of the anxiety associated with interactions with cultural difference, will be discussed more in the next section.

Early studies in the organizational arena, however, focused largely on issues of expatriation. An expatriate (or more popularly referred to as an “expat”) is an employee who voluntarily leaves his or her country for a temporary assignment in a foreign country. Black and Gregersen (1999) summarize much of the knowledge in this arena into three general areas of best practice: sending the right people (selection) for the right reason (strategy) and providing the right ending (repatriation). Much of the literature is based on the argument that the expatriate failure rate is uncharacteristically high. Research has identified a number of individual factors (e.g., personality attributes, willingness to relocate, family issues) and organizational factors (e.g., lack of or ineffective selection, orientation, compensation, and training systems) that are attributable to expatriate failure. Research in this area is valuable given the significant organizational cost associated with expatriating and repatriating employees.

While global management research finds its roots in the types of issues just discussed, it is critically different in the following way: Global management is concerned with the interactions of leaders across multiple country and cultural contexts, while international or expatriate management focuses on the interactions of a manager within a single culture. This difference will come more into focus in the following discussion.

Global Organizations

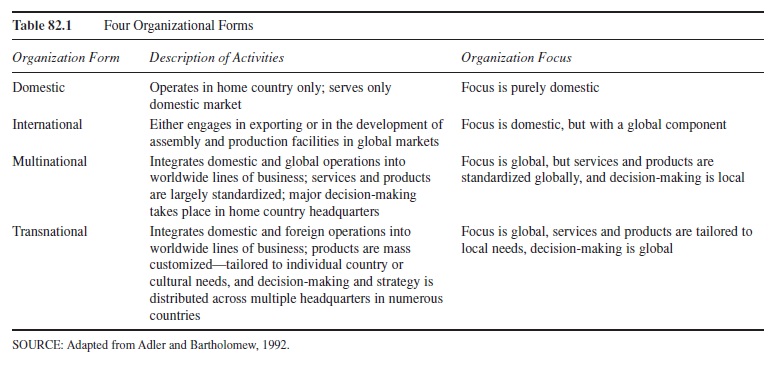

The world of the global organization is one in which variety, complex interactions among various subunits, host governments, customers, pressures for change and stability, and intricate webs of networked relationships are the norm. Although there is no universally accepted definition of a global organization, there is general consensus that an organization evolves through distinct stages or forms as it globalizes. To illustrate, consider the framework in Table 82.1.

As an organization progresses through the various stages from domestic to global, there is an increase in the complexity of its structure, strategy, and systems. A key characteristic, as defined by Bartlett and Ghoshal (1989) in their seminal book, Managing Across Borders, is that global organizations operate across national boundaries, simultaneously achieving global integration while retaining local differentiation. The central component of this definition is that a global organization achieves across country coordination, allowing it to capture global-scale economies while also responding to local needs. For example, Rhinesmith (1993) writes that global organizations “think globally and act locally” while Prahalad and Doz (1987) state that “globalization”—the process of managing cross-country coordination while simultaneously capturing and responding to local need—is central to global competitiveness.

Table 82.1 Four Organizational Forms

Table 82.1 Four Organizational Forms

To balance local and global forces, structure, strategy, and systems must be determined by the task. Some activities of the organization may be organized geographically, some by function, and some by product line. For example, a global organization whose product is sports apparel might design the clothing in the United States, secure the fabric in China, manufacture it in Pakistan, and sell it through a chain of stores located in the United States, Canada, Europe, Singapore, and Japan. All of the activities of these organizations are planned, managed, coordinated, and led from a central office that may be located anywhere in the world. If the political climate becomes too unstable in China, sourcing can be moved to Mexico; if labor costs become too expensive in Pakistan, manufacturing can be relocated to Bangladesh. Because time-to-market is of critical importance in the sports apparel industry, the company may have two factories, one in Pakistan and one in Bangladesh, each operating at half capacity, so that in the event of instability one can be shut down and the other can take up the slack without missing a beat.

Expand this example for every product the company has—shorts, bathing suits, baseball caps, sweat suits— each with the potential for a shared or different process of sourcing, manufacturing, distributing, and selling, and we see the world of the global organization. Rhinesmith (1993) emphasizes that this type of organization represents a wholly new paradigm for management. It requires organizational alignment along three broad dimensions: (a) strategy and structure, (b) corporate culture, and (c) people. Of the three dimensions, people are the critical factor because it is through people that the strategy, structure, and corporate culture are enacted. No strategy, no structure, and no corporate culture can operate without people who can actually do the job.

Global Management

As stated earlier, the term “global management” is defined by its context. The common theme across the past discussion is one of increasing complexity as the organizational context shifts from domestic to global. Thus, global management can be defined within this context as processes of leadership enacted across the complex, interacting boundaries of distance, country, and culture (Dalton, Ernst, Deal, & Leslie, 2002):

- Distance refers to the complexity that accrues working within and across physical distance. Because leaders in global organizations work across distance, they must effectively negotiate multiple time zones, monitor information around 24-hour business cycles, and work with others that they cannot see (e.g., virtual management, geographically dispersed teams).

- Country refers to the complexity that accrues working within and across national infrastructures. Because leaders in global organizations work across countries, they must effectively address multiple political and regulatory structures, economic systems, currency variations, and civic and labor practices.

- Culture refers to the complexity that accrues working within and across cultural differences. The world is marked throughout by incredible diversity in language, thought, norms, rules, and organizing principles. The interactions of these social processes are often laden with tension and ambiguity. Because leaders in global organizations work across cultures, they must interact with diverse individuals and multicultural teams, with basic and fundamental differences in norms, beliefs, and values.

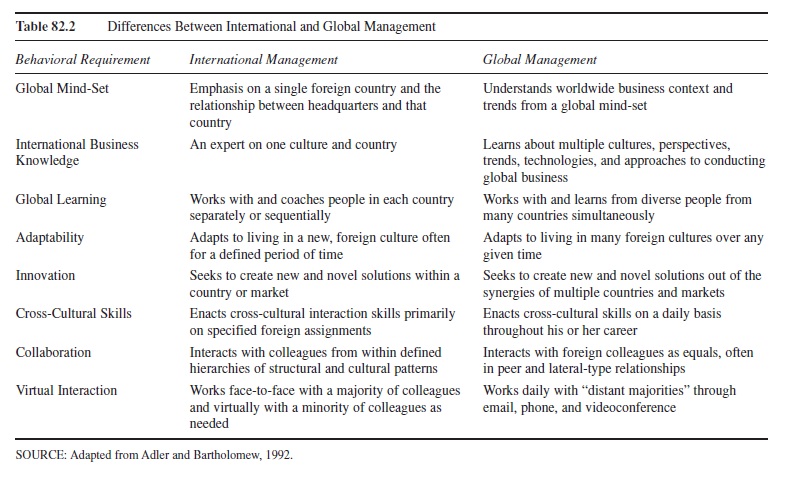

Table 82.2 Differences Between International and Global Management

Table 82.2 Differences Between International and Global Management

When we multiply each of these dimensions by the number of time zones, countries, and cultures in which a manager works, the complexity becomes more evident. When you schedule a teleconference, there is often a person in a different time zone at the other end of each line. When you are sitting in a meeting, say in Japan, you must be aware of the Japanese differences in currency exchange rates, corporate governance, political legislation, and unions while also keeping in mind the country infrastructure of the multiple locations in which your company does business. When you get off a plane, a different set of cultural expectations waits for you at the gate.

As this discussion illustrates, the context of the global manager is one of increasing complexity, requiring leaders to work simultaneously across borders of physical distance, country infrastructures, and cultural expectations. Central to the definition is the need to work simultaneously and from a distance with individuals from multiple cultures. As described by Adler,

Global leadership theory, unlike its domestic counterpart, is concerned with the interaction of people and ideas among cultures, rather than with either the efficacy of particular leadership styles within the leader’s home country or with the comparison of leadership approaches among leaders from various countries—each of whose domain is limited to issues and people within their own cultural environment. (1997, p. 175)

As the form of an organization evolves, the environment imposes a more complex set of management demands. Some of these differences are shown in Table 82.2.

Table 82.2 suggests that the general behavioral requirements—for example, a “global perspective”—are the same, but that the level of difficulty and consequently the level of skill are greater when an organization’s form shifts from international to global. Whereas leaders in an international organization focus on a single foreign country, leaders in a global organization must understand and operate within the worldwide business environment. It is the infinite variety of factors that exist within this worldwide environment that render it qualitatively and quantitatively different. It is the added complexity that accrues working across the intersections of distance, country, and culture that is the hallmark of management in the global context.

Concepts: Exploring The Key Principles Underlying Global Management

There is no Holy Grail, no magic bullet, no rosette stone of global leadership. The riddle has many answers.

—George Hollenbeck

No single unifying concept frames the topic of global management. Global management is better considered a unique context for leadership in which multiple concepts can be developed. For the scholar or practitioner of global management, you will encounter many views and a varied set of ideas. Here we turn to discuss some of the most frequently referenced concepts. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list; rather, the hope is to define the key terms in the literature.

Culture Shock

Oberg (1960), a pioneer in studying cross-cultural adjustment, coined the term culture shock. As mentioned earlier, this concept was originally constructed to describe the adjustment experience of a sojourner or expatriate to another culture. Oberg defines culture shock as the anxiety that results from an individual’s attempt to process and understand how the world works in a different cultural context. Culture shock is a form of anxiety that results from the misunderstanding of commonly perceived and understood signs of cultural interaction. Interestingly, Adler’s (1997) research treated culture shock as a developmental opportunity rather than an obstacle to overcome. The shock associated with cultural difference allows a person to understand the relativity of his or her own value set and then investigate, reintegrate and reaffirm a relationship to others. Whether it is viewed as a challenge or an opportunity, culture shock is a concept many of us have experienced in our interactions across cultures.

Global Mind-Set

The phrase “global mind-set” lacks a single definition and has become an umbrella concept to describe the constellation of skills, knowledge sets, and attitudes of effective global leaders. The global mind-set is most often defined as a state of mind—a perspective for viewing the world in which any business, industry sector, or particular market is viewed on a global basis. For example, Gupta and Govindarajan (2002) define a global mind-set as the ability to combine an openness to diversity across cultures and markets while also being adept at synthesizing across this diversity. The key is that leaders with a global mind-set have the ability to see across multiple territories and focus more on commonalities across markets rather than emphasizing the differences amongst countries.

Global mind-set is generally considered an attribute of a person; however, more recent literature has described it in terms of an organizational capability. Begley and Boyd (2003) argue that it is no longer sufficient for a limited number of executives to have a global mind-set. They describe a “corporate global mind-set” as a competitive advantage in which the organization is capable of developing and interpreting criteria for business performance that is not subject to models from any one country, culture, or context and can implement those criteria in an appropriate way across global contexts. Central to this organizational capability is the capacity to balance and adjudicate between two forces that are inherently in conflict with one another: global consistency and local responsiveness.

Regardless of whether global mind-set is defined at an individual or organizational level, the concept of global mind-set is firmly established in the lexicon of global management.

Cultural Adaptability

The concept cultural adaptability, like global mind-set, has a rich and varied history. It can be defined as the motivation and ability to adapt one’s behavior to the established norms, values, beliefs, and customs that prevail as a societal-level prototype in a given geographical location (Deal, Leslie, Dalton, & Ernst, 2003). As the concept is understood in the literature, cultural adaptability involves a motivation to understand culture, a sensitivity to differences between cultures, an ability to change behavior to fit with new environments, and the skill to learn about and adapt to cultural differences.

In an article published nearly 20 years ago, Ratiu (1983) was one of the first to examine the role of cultural adaptability in determining the success of global leaders, or “internationalists.” One characteristic of successful internationalists, Ratiu argued, is that they begin with general knowledge or prototypes of cultures when first dealing with different cultures. As they get to know people from those cultures as individuals, however, successful internationalists let go of or adjust elements of their prototypes and gain a less stereotypical knowledge of the cultures and their people. Unsuccessful internationalists either do not start with prototypes (and as a result interpret everything based on their own mental frameworks) or are unable to discard their prototypes despite evidence gathered from their relationships with people from other cultures that ought to dispel these preconceptions.

More recent research has looked at the relationship between cultural adaptability and job effectiveness. For example, Spreitzer, McCall, and Mahoney (1997) found that boss ratings of an individual’s potential success as an international executive were related to ratings of cultural adaptability. To become better grounded in the concept of cultural adaptability, the reader may want to also consult literature in the areas of interpersonal adjustment, international experiences, and cross-cultural training.

Cross-Cultural Values

Extending from the work of Hofstede (1980) in his pioneering book, Culture’s Consequences, research into differences in cross-cultural values has spanned the social sciences including psychology, sociology, communications, and anthropology. Other well-known researchers in this area include Shalom Schwartz, Harry Triandis, and Fons Trompenaars. Value studies involve collecting large samples of individual-level data within culture and then drawing aggregate comparisons across cultures. The result is a framework or model to explain similarities and differences in cultural values. Within the business arena, the cultural dimension of individualism (more associated with the West) and collectivism (more associated with the East) has been used to explore differences in everything from collaboration to conflict and from mergers and acquisitions to performance appraisal.

While relevant to global management, research in this area is limited in producing results that are broad enough to impact the cross-boundary operating reality of global leaders. One exception comes from the current GLOBE project (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004). The GLOBE project is exemplary in that its findings are based on a sample of approximately 17,000 middle managers working in 900 organizations from three sectors in 62 countries around the world. The project seeks to refine societal cultural dimensions and link these dimensions to organizational culture and leadership. Of specific interest to global management is the set of leadership characteristics that were identified in the research as being universally positively endorsed by people in most countries in the sample. For example, attributes such as trustworthiness, dependability, and intelligence were endorsed as being associated with effective leadership across continents and cultures. Yet, it is important to note that the relative importance of each of these characteristics, as well as the specific behaviors that exemplifies these characteristics, varies from country to country.

Cultural Intelligence

In their book, Earley, Ang, and Tan (2005) describe cultural intelligence (also known as cultural quotient or CQ) as a person’s capability to function effectively in situations characterized by cultural diversity. Cultural intelligence is an individual capability that distinguishes intelligence as more than cognitive ability. Like other types of intelligence (e.g., interpersonal, emotional, social), cultural intelligence focuses on capabilities that are important for high-quality personal relationships. As such, it provides insights into how leaders address multicultural situations, engage in cross-cultural interactions, and perform in culturally diverse work groups.

As a relatively new area of inquiry, cultural intelligence builds on each of the concepts previously discussed. A strength of CQ is that it can be measured through a 20-item scale measuring the four dimensions—CQ-Strategy, CQ-Knowledge, CQ-Motivation, and CQ-Behavior. Early research has linked cultural intelligence with effective decision making in intercultural situations and with adjustment perceptions in culturally diverse situations. Further study in this area will be helpful in understanding the antecedents and consequences of CQ and how it is similar or different from other types of intelligence.

Learning to Learn

Several decades’ worth of research at the Center for Creative Leadership demonstrates that the ability to learn from experience is related to effectiveness in a variety of leadership roles and contexts. For example, McCall, Lombardo, and Morrison (1988) found that about 70% of the important lessons that effective managers had learned about their work were developed from a variety of challenging experiences and critical relationships. Similar types of findings have now been replicated with global manager populations by McCall and Hollenbeck (2002) and by Dalton, Ernst, Deal, and Leslie (2002). Specifically, these studies show that it is the unique lessons learned from culture that differentiate the developmental pathways for effective global leaders as compared to domestic leaders.

The implication of research in this area is that individuals or organizations that aspire to develop global management capabilities should support and seek out the following kinds of international assignments: international business trips, membership on cross-cultural teams, management responsibility for a cross-cultural team, expatriate assignments, responsibility for products, services, or processes in more than one country, and opportunities to work with experienced global executives. Each of these assignments provides a different kind of stretch and the opportunity for both cumulative and differentiated learning to occur. Further, the developmental impact of these assignments (as well as other learning opportunities) will be enhanced to the extent that they contain a rich mixture of three primary strategies: assessment, challenge, and support.

Global Leader Competencies

As the competency movement remains pervasive in the human resources and leadership development fields, there is no shortage of competencies to describe effective global management. Competencies consider the knowledge, skills, abilities, motivations, and perspectives that are believed to be associated with leadership effectiveness. As such, they focus on characteristics of the individual manager. In the literature, global leaders are characterized by such colorful descriptions as cultural synergizers, true planetary citizens, cross-fertilizers, cosmopolitans, and perpetual motion executives.

In addition to these descriptions, the current literature is replete with taxonomies and lists of various traits and skills believed to be associated with effective global leadership. These lists are derived from organizational researchers and practitioners through case studies, interviews, and observations. For example, Kanter’s (1995) model involves the 3Cs— concepts, competence, and connections. Gregerson, Morrison, & Black (1998) identified the competencies of inquisitiveness, personal character, duality, and savvy; and Rosen (2000) called for the new “global literacies” of leadership to include personal literacy, social literacy, business literacy, and cultural literacy. This is just a small sample of the literature associated with the burgeoning competency movement. As will be discussed in the section that follows, there are both strengths and limitations associated with this ever-growing body of knowledge.

Current Directions: Global Management Research In The 21st Century

Research on global managers is relatively scarce. Besides defining what the global manager’s competencies and behaviors should be . . . studies are still mainly at the conceptual stage.

—Vladimir Pucik and Tania Saba

The major strength of the literature covered to this point is that it is rich in description. Research conducted over the course of the past decade—some of which has been conducted by top researchers in the field of organizational studies—has adequately defined the characteristics of global organizations and global management. We now have a clearer understanding of what a global organization is, as well as the roles and responsibilities of leaders who work within these organizations. Global managers and organizations function across distance, country, and cultural borders. At both the individual and organizational level, the literature is consistent that the net effect of functioning across country borders is heightened complexity. The degree of overlap and agreement concerning this effect is striking.

The major limitation of the reviewed literature is that it is theory poor. In its effort to describe the context and concepts of global management, the literature runs the risk of incoherence. Although there is overlap in the concepts and competencies just discussed, it is difficult to know which description is the best or most appropriate. Further, without a theoretical framework, it is challenging to attempt and replicate study findings and build an integrated base on knowledge. Clearly, the literature has reached a point of diminishing returns in which it is no longer helpful to create additional global leader competencies. What is of significant value, however, is research to link global management to existing and emerging theory. To help encourage future thinking in this direction, several of the more promising theories are described next. Each of the following theories could be used to anchor future papers on global management.

Behavioral Complexity

Behavioral complexity, developed in a recent line of research conducted by Hooijberg and colleagues (Hooijberg, Hunt, & Dodge, 1997; Hooijberg & Quinn, 1992) is defined as the ability to both perform and adapt to multiple behavioral roles as dictated by the organizational and environmental context. The construct is theorized to have a repertoire and a differentiation component. Behavioral repertoire refers to the portfolio of roles that a leader can perform and behavioral differentiation refers to the ability of leaders to vary the performance of their roles depending on the situational context. The notion of behavioral complexity gives recognition to the fact that leaders are embedded in a dynamic, evolving environment and therefore must be able to assume different, contradictory, or even competing roles in different times and situations.

Related to global management, a central proposition of research in this area is that if complexity is a defining characteristic of the environment, then behavioral complexity—defined in terms of the ability to perform and to adapt multiple roles—must also be reflected in the capacities of the effective leader. Beyond more static behavioral or contingency leadership models, this proposition lends itself nicely to the types of complexity associated with global management. The development of multiple and diverse roles, and the ability to adapt roles to the situation, might be one way in which global leaders can work effectively and meet the demands of an increasingly complex, global business environment.

Social Identity Theory

As global managers increasingly interact with others who belong to different social and cultural groups, one may wonder if the world will become “small” enough that individuals may define themselves not as much as members of a particular cultural, racial, or ethnic group, but rather as members of the human race. The psychological theory of social identity suggests that this is not likely because of the well-established human tendency to categorize people into groups of “people like me” and “people not like me.”

In their book Intergroup Behavior, Turner and Giles (1981) write that social identity theory presumes that an individual’s self-concept is derived from membership in a social group together with the emotional value attached to that membership. Social identity theory suggests that individuals engage in a cognitive process in which they classify themselves and others into categories or groups. This categorization process serves two functions: it provides individuals with a systematic means of defining others, and it allows the individual to define him- or herself within the social environment.

If the essence of global management is about bringing groups of people together across distance, countries, and cultures, then social identity theory is helpful in understanding the boundary conditions and challenges that global leaders face. Due to powerful forces such as globalization, technology, shifting social structures, and evolving organizational forms, the demographics of the workforce will become yet more diverse in the 21st century. Groups of people who have historically remained apart are now “colliding” in the workplace. For example, we see Protestants and Catholics working together for U.S. computer companies in Northern Ireland or Blacks and Whites collaborating in a post-Apartheid South Africa. Papers exploring the linkages between global management and social identity will be helpful in better understanding the role of leadership in these emerging contexts of difference.

Boundary Role Theory

A “boundary” is defined as a type of border, barrier, or limit. As daily life is largely about navigating or crossing various barriers and limits, research has examined the challenges and opportunities associated with organizational boundaries. Seminal papers on boundary roles or boundary spanning include Adams (1976) description of the “boundary role person,” Tushman’s (1977) explication of boundary spanning and innovation processes, and Ancona’s (1992) work on boundary-spanning teams. Currently, the boundary-spanning literature focuses primarily on crossing or spanning interorganization, team-organization, and organization-environment boundaries. Within a leadership context, Alter and Hage (1993) describe a boundary spanning leader as “one who works across organizational or sectoral divides to build common commitment to action on a particular policy or practice issue.”

The work of global management requires leaders to integrate and coordinate activities across boundaries of distance, country, and culture. Preliminary research that I conducted demonstrated that practicing global leaders viewed external boundary-spanning roles such as serving as a spokesperson or liaison as being more important to perceptions of their job effectiveness than more internal-facing, organization-centric roles. Global management requires cutting across boundaries in order to move ideas, information, decisions, talent, and resources wherever they are needed most. Research on boundary spanning and global management will be helpful in addressing questions such as, What are the role demands for global managers? What traits are required for such a role? What activities are performed by boundary-spanning leaders? How do boundary spanners reach across social and organizational barriers and divides?

Connected or Relational Management

Research in the area of connected or relational leadership works from the assumption that leadership is less about the unique properties of individual leaders and more about the dynamic relationships that bind groups of people together. From this perspective, leadership can be defined as the collective activity of groups of people to set direction, maintain alignment, and gain commitment (McCauley & Van Velsor, 2004). By viewing leadership as an outcome to be achieved by the organization or collective rather than a skill or role that a person possesses, it becomes possible to view leadership from a broader, more inclusive lens. According to this definition, leadership would be exercised when a CEO articulates a compelling mission that sets organizational direction; when a cross-functional group reaches across organizational boundaries to align IT systems; and when organizational members come together to confront a complex challenge and develop greater trust and respect through their interactions.

As discussed earlier in this research-paper, the majority of current research looks at the unique competencies and skills of effective global leaders. This research is limited in that (a) it is difficult to break global management effectiveness down into discrete components, (b) competencies are static and cannot adapt to changes in the dynamic global context, and (c) there is more than one kind of effective global manager. Improving upon these shortcomings, future global management research would benefit from taking a whole systems relational approach. These studies could bring new understanding of what leadership looks like in networked, inter-dependent, team-based organizations. Further, they could help diverse and global populations identify new ways to view power, resources, and decision making as a property of the whole rather than simply the “person in charge.” Finally, connected or relational leadership approaches could open new methods for leadership development that seek to develop the linkages and connections that glue people together in global organizations.

Corporate Social Responsibility

An important debate is taking place in the 21st century concerning the role of global business in the broader society. Upbeat participants in this debate feel that global business will provide worldwide growth and development opportunities. According to this viewpoint, the economic impact of globalization will create employment opportunities for the world’s impoverished, help create desperately needed infrastructure in developing economies, and contribute to the correction of global social challenges. Others, far less optimistically, believe that global business will lead to further and continued exploitation of foreign workers, the continued cycle of dependency between the developed and developing world, and the accelerated destruction of natural resources and local cultures. Proponents of this point of view argue that the forces driving global business will undermine the power of local and national governments and will weaken the ability of policymakers to control key social and economic processes.

Finally, between these two extremes are those who hold a more balanced perspective. Under the theoretical umbrella of “corporate social responsibility” or “CSR,” advocates of a balanced position argue that in a compressed and interconnected world, global business and the broader society must work together to the mutual benefit of one another. Global organizations by their very existence have an impact within the social fabric of countries and therefore bear a responsibility for working with religious organizations, governments, and nongovernmental organizations to strengthen that fabric.

Regardless of perspective, the implication of this debate is that in today’s interconnected world, developing political, social, and environmental awareness and knowledge is an integral aspect of a global leader’s job, not something separate from it. Through the decisions they make in promoting the interests of their businesses, global leaders affect the well-being of people in multiple cultures and the practices of business in multiple countries. As such, global managers have a responsibility to understand what positions they are taking through their actions and must be prepared to revisit, renew, and revise those positions over time. To support leaders in this endeavor, future research is needed to determine the role of global business at the intersection of the organization with broader social, economic, political, and environmental forces.

Current Directions: Global Management Practice In The 21st Century

The clear issue is that the strategy (the what) is internationalizing faster than implementation (the how) and much faster than individual managers and executives themselves (the who). The challenges are not the “what” of what-to-do, which are typically well-known. They are the “hows” of managing human resources in a global firm.

—Nancy Adler and Susan Bartholomew

As globalization continues to accelerate in the 21st century, organizations will remain challenged to keep pace. While the previous section examined linkages that could be drawn between global management and theory, this final section looks at the connections between global management and practice. Specifically, we examine the implications of global management for a number of applied topics including selection, performance appraisal, talent management, leadership development, and organizational culture. Successful organizations are required to create, modify, or adopt human resource systems and processes to mesh with the needs of an increasingly global business environment. As you will see, each of the following topics are “the same, but different” when framed in the global vis-à-vis a domestic management context.

Selection

Selection involves the identification, recruitment, and hiring of people to fill the human capital needs of an organization. A widely noted criticism of many selection processes is that they assume that past performance is the best predictor for future performance. This critique is especially pertinent in the global arena. As has been discussed throughout this research-paper, the skills that are needed to be effective globally are in many ways unique from the skills needed for effectiveness in a domestic context. Hiring global leaders solely based on their performance in domestic roles will surely prove a limited strategy.

The selection of leaders for global roles must broaden beyond past performance to include a consideration of international experience and interest. A first step in the process is for organizations to identify people early in their careers who show a liking for travel, novelty, and international work, who speak other languages, and whose life experience includes time spent living in foreign locations. Each of these can serve as markers for identifying future global talent.

Another step involves assessing for global management skills. Many of the concepts in this research-paper such as cultural adaptability or cultural intelligence can be measured. A third step involves using role plays or simulations to observe candidates in practice. Using these methodologies, it becomes possible to observe behaviors such as adaptability and flexibility that are critical for effectiveness in global roles. While some aspects of the employee-selection process can remain intact, other aspects need to be tailored given the unique demands of global management.

Performance Appraisal

Performance appraisals are regular reviews of employee performance within organizations. A common approach to assessing performance is to use a numerical rating in which managers are asked to evaluate an individual against a number of standardized objectives. The challenge for traditional performance approaches, however, is that the standards for performance vary from country to country. That is, the definition of what makes for an effective global manager is culturally contingent.

Derr and Laurent (1989) conducted a now classic study of what American and European managers believe constitutes effective managerial performance. They found that Germans value managers who are technically creative and competent. The French value managers who have the ability to manage power relationships and work the system. The British value managers who create the right image. Americans value entrepreneurial behavior. Certainly this list would be even more varied and complex if extended to also include leaders from Africa, the Middle East, Asia, South America, and beyond.

Given these realities, organizations will increasingly need to create more flexible performance appraisal systems. One option is to create two sets of appraisal objectives— one set that is universal across cultural and country contexts and another that is responsive to local needs. A second option may be to keep the objectives fixed, but to allow freedom in defining the specific behaviors and attributes that constitute the objective. For example, “being decisive” could be a fixed objective globally, while the behaviors that demonstrate effectiveness could vary across countries. Yet a third option is for an organization to focus its performance appraisal on a more limited set of objectives that transcend cultural boundaries.

Of all the concepts previously discussed, the ability and willingness to “learn from experience” stands out as a metacompetency for effectiveness in today’s organizations. Learning behaviors include accepting or seeking out new and unfamiliar challenges, persistence in the effort to master a difficult task, the demonstration of a willingness to learn from the experience of others, a willingness to admit not knowing how to do something, and an openness to feedback about one’s efforts and impact. Of course, even evidence of the willingness to learn is culturally contingent. Yet, without question, the ability to learn from experience and adapt accordingly is a hallmark for effective global leaders in the 21st century.

Talent Management

Talent management is a comprehensive phrase that focuses on the proactive management of people throughout the employee life cycle. Effective talent management systems involve a global approach in which the best and brightest are identified, developed, and promoted wherever in the world they may be located. Unfortunately, it is common knowledge in many international organizations that only people who are native to the organization’s home country will ever be promoted beyond a certain level. This kind of practice, whether unconscious or intentional, will cause employee morale, commitment, and retention problems around the world. Talented employees are unlikely to remain with organizations if they know that they are trapped below a country-based “glass ceiling.”

This practice has important implications for an organization’s global strategy. There are three visible indicators of how serious an organization is about its global intentions—the composition of the board of directors, the executive team, and the talent pool. To the extent that the board of directors and executive team are monocultural, the organization is not yet global. To the extent that the talent pool is comprised of people from one or a very limited number of countries, the company is not fully harnessing the capabilities of its people. As such, an important human resource task is to open the talent pool worldwide. The management development process should include candidates from every geographic location of strategic importance.

Leadership Development

In a survey conducted with senior executives in 108 Fortune 500 companies, Gregersen, Morrison, and Black (1998) found that having skilled global leaders was the single most important factor cited in achieving global success, more so than factors such as financial resources, political stability, tariff/trade restrictions, and information technology. Yet, these same executives felt that their present supply of global leaders did not meet the organizational needs. Eighty-five percent felt that they did not have an adequate number of global leaders, and 67% felt that their existing global leaders needed additional development. To reverse these trends in the future, leader development (focused on developing the attributes of individuals) and leadership development (focused on developing overarching leadership systems and cultures) will need to become an organizational imperative.

Organizations can use a number of processes to develop global managers including individual development planning, training, 360-degree feedback, action learning, mentoring, and coaching. In addition to these methodologies, the development of global leaders requires an intentional and systematic focus in providing on-the-job experience. Simply stated, there is no substitute for cross-cultural experience as the foundation to any process of development for effective global leaders. These experiences should be graduated along a continuum of challenge and complexity ranging from international assignments to having worldwide responsibility for a key organizational product or process.

Organizational Culture

A final applied topic for consideration is to examine the overall culture or climate in which global managers operate. Organizational culture comprises the attitudes, experiences, beliefs, and values of an organization. It impacts everything from the ways in which people interact inside the organization to stakeholder relationships outside the organization. Further, no matter how effective a global manager may be individually, he or she will be limited if the culture itself does not support global organizational values.

Finally, the culture itself will not be globally effective unless large numbers of employees begin developing more globally diverse mindsets and orientations.

Friedman (2005) points out in The World Is Flat that globalization has gone through three distinct stages. In Globalization 1.0 (1492 to 1800), based on the activities of globalizing nations, the world shrank from a size large to a size medium. In Globalization 2.0 (1800 to 2000), spearheaded by globalizing markets and corporations, the world shrank from a size medium to a size small. Now, in Globalization 3.0 (starting around 2000), the world is rapidly shrinking from a size small to a size tiny. And while countries and companies were the dynamic force behind the earlier stages of globalization, today it is the activities and behaviors between linked-up individuals and small groups that add further fuel to Globalization 3.0.

The implication of these sweeping societal changes is that “global management” will no longer be the domain of the few in the 21st century, but rather will rest in the hands of the many. Leaders in many levels and types of organizations will increasingly find themselves working simultaneously across the interacting boundaries of distance, country, and culture. And importantly, unlike the European and American leaders and organizations that largely drove the earlier stages of globalization, future global managers will be much more diverse and hail from the global community of nations. Organizations that can foster cultures to embrace this tremendous diversity will be at a distinct advantage in the 21st century.

Conclusion

The purpose of this research-paper was to outline the key contextual issues, concepts, and current directions that inform the topic of global management. A common thread throughout the research-paper was that global management can only be properly understood within its context, a context requiring leaders to work across interacting boundaries of distance, country, and culture. In an increasingly diverse and interconnected world, we are advancing toward a time in which all leadership, by definition, will become global in scope. Thus, research and inquiry into this topic will remain timely and relevant for management throughout the 21st century.

References:

- Adams, S. (1976). The structure and dynamics of behavior in organizational boundary roles. In M. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1175-1199). Chicago: Rand McNally.

- Adler, N. J. (1997). Global leadership: Women leaders. Management International Review, 37(1), 171-196.

- Adler, N. J., & Bartholomew, S. (1992). Managing globally competent people. Academy of Management Executive, 6(3), 52-65.

- Alter, C., & Hage, C. (1993). Organizations working together. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Ancona, D. G., & Caldwell, D. F. (1992). Bridging the boundary: External activity and performance in organizational teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(4), 634-665.

- Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1989). Managing across borders: The transnational solution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Begley, T. M., & Boyd, D. P. (2003). The need for a corporate global mind-set. MIT Sloan Management Review, 44(2), 25-32.

- Black, J., & Gregersen, H. (1999, March/April). The right way to manage expats. Harvard Business Review, 77(2), 52-62.

- Dalton, M., Ernst, C., Deal, J., & Leslie, J. (2002). Success for the new global manager: How to work across distances, countries and cultures. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Deal, J., Leslie, J., Dalton, M., & Ernst, C. (2003). Cultural adaptability and leading across cultures. In W. Mobley & P. Dorfman (Eds.), Advances in global leadership (Vol. 3, pp. 149-166). San Francisco: JAI Press/Elsevier Science.

- Derr, C. B., & Laurent, A. (1989). The internal and external careers: A theoretical and cross cultural perspective. In M. Arthur, D. T. Hall, & B. S. Lawrence (Eds.) The handbook of career theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Earley, P. C., Ang, S., & Tan, J. S. (2005). CQ: Developing cultural intelligence at work. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Friedman, T. (2005). The world is flat. New York: Farrer, Straus, & Giroux.

- Gregersen, H., Morrison, A., & Black, S. (1998). Developing leaders for the global frontier. Sloan Management Review, 40(1), 21-32.

- Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. (2002). Cultivating a global mindset. Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 116-126.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Cultures consequences: International differences in work-related values. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Hooijberg, R., Hunt, J., & Dodge, G. (1997). Leadership complexity and development of the leaderplex model. Journal of Management, 23(3), 375-408.

- Hooijberg, R., & Quinn, R. E. (1992). Behavioral complexity and development of effective managers. In R. L. Phillips & J. G. Hunt (Eds.), Strategic leadership: A multiorganizational-level perspective. Wesport, CT: Quorum.

- Hollenbeck, G. P. (2001). A serendipitous sojourn through the global leadership literature. In W. H. Mobley & M. W. McCall (Eds.), Advances in global leadership (Vol. 2, pp. 15-48). San Francisco: JAI Press/Elsevier Science.

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Leadership, culture, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Kanter, R. M. (1995). World class: Thriving locally in the global economy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- McCall, M. W., & Hollenbeck, G. P. (2002). The lessons of international experience: Developing global executives. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- McCall, M. W., Jr., Lombardo, M. M., & Morrison, A. M. (1988). The lessons of experience: How successful executives develop on the job. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- McCauley, C., & Van Velsor, E. (2004). The Center for Creative Leadership handbook of leadership development (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley Publishers.

- Oberg, K. (1960). Culture shock: Adjustment to new cultural environments. Practical Anthropology, 7, 177-182.

- Parker, B. (1996). Evolution and revolution: From international business to globalization. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of organization studies (pp. 484506). London: Sage.

- Pucik, V., & Saba, T. (1998). Selecting and developing the global versus the expatriate manager: A review of the state-of-the-art. Human Resource Planning, 21(4), 40-54.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Doz, Y. L. (1987). The multinational mission: Balancing local demands and global vision. New York: Free Press.

- Ratiu, I. (1983). Thinking internationally: A comparison of how international executives learn. International Studies of Management and Organization, 13(1-2), 139-150.

- Rhinesmith, S. H. (1993). A manager’s guide to globalization: Six keys to success in a changing world. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin.

- Rosen, R. (2000). Global literacies: Lessons on business leadership and national cultures. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Spreitzer, G. M., McCall, M. W., & Mahoney, J. D. (1997). Early identification of international executive potential. Journal of

- Applied Psychology, 82(1), 6-29. Turner, J. C., & Giles, H. (Eds.). (1981). Intergroup behavior. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Tushman, M. L. (1977). Special boundary roles in the innovation process. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(4), 587-605.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.