This sample Consumer Psychology Research Paperis published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality research paper on any topic at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Consumer psychology is the study of the processes involved when individuals or groups select, purchase, use, or dispose of products, services, ideas, or experiences to satisfy needs and desires. The decision to consume typically is the culmination of a series of stages that include need recognition, information search, evaluation of alternatives, purchase, and post purchase evaluation. However, in some cases (especially when involvement with the product or service to be chosen is low), this rational sequence is short-circuited as consumers make decisions based on ‘‘shortcuts’’ called heuristics (e.g., ‘‘Choose a well-known brand name’’). In other cases (especially when involvement with the product or service to be chosen is especially high, as is the case with extremely risky decisions or when the object carries extreme emotional significance to the individual), subjective criteria also may cause the person’s choice to diverge from the outcome predicted by a strictly rational perspective on behavior. Indeed, many consumer behaviors, including addictions to gambling, shoplifting, and even shopping itself, are quite irrational and may literally harm the decision maker. The study of consumer psychology underscores the importance of individual and group variables that help to shape preferences for products and services. In addition to demographic differences such as age, stage in the life cycle, gender, and social class, psychographic factors such as personality traits often play a major role. A person’s identification with others who constitute significant reference groups or who share the bonds of subcultural memberships also exerts a powerful impact on his or her consumption decisions. These macro influences on behavior make it more or less likely that an individual will choose to adopt new products, ideas, or services as these innovations diffuse through a market or culture.

Outline

- I Buy, Therefore I Am

- Consumers as Decision Makers

- Psychological Influences on Consumption

- Cultural and Interpersonal Influences on Consumption

1. I Buy, Therefore I Am

Consumer psychology is the study of the processes involved when individuals or groups select, purchase, use, or dispose of products, services, ideas, or experiences to satisfy needs and desires. The field embraces many kinds of consumption experiences, ranging from canned peas, a massage, or democracy to hip-hop music or a celebrity such as Madonna. Needs and desires to be satisfied range from physiological conditions such as hunger and thirst to love, status, or even spiritual fulfillment.

Consumers take many forms, ranging from an 8-yearold girl begging her mother for Poke´ mon cards to an executive in a large corporation deciding on a multimillion-dollar computer system. This research paper focuses on individual consumers, but with the caveat that many important issues relate to the psychology of group decision making involving dyads, families, and organizations. One must also recognize that the study of consumer behavior is extremely interdisciplinary. Although psychology is one of the core disciplines that have shaped the field, many other important perspectives from economics, sociology, and other social sciences also play a dominant role.

During its early stages of development, the field was often referred to as buyer behavior, reflecting an emphasis on the exchange, a transaction in which two or more organizations or people give and receive something of value. Most marketers now recognize that consumer behavior is in fact an ongoing process and not merely what happens at the moment a consumer hands over money or a credit card and, in turn, receives some good or service. This expanded view emphasizes the entire consumption process, which includes the issues that influence the consumer before, during, and after a purchase.

One of the fundamental premises of the modern field of consumer psychology is that people often buy products not for what they do but for what they mean. This principle does not imply that a product’s basic function is unimportant; rather, it implies that the roles that products play in our lives extend well beyond the tasks that they perform. The deeper meanings of a product may help it to stand out from other similar goods and services. All things being equal, a person will choose the brand that has an image (or even a personality) consistent with the purchaser’s underlying needs.

People’s allegiances to certain sneakers, musicians, or even soft drinks help them to define their place in modern society, and these choices also enable people to form bonds with others who share similar preferences. Following are some of the types of relationships a person might have with a product:

- Self-concept attachment. The product helps to establish the user’s identity.

- Nostalgic attachment. The product serves as a link with a past self.

- The product is a part of the user’s daily routine.

- The product elicits emotional bonds of warmth, passion, or other strong emotion.

Self-concept refers to the beliefs that a person holds about his or her own qualities and how he or she evaluates these qualities. People with low self-esteem may choose products that will enable them to avoid embarrassment, failure, or rejection. For example, in developing a new line of snack cakes, Sara Lee found that consumers low in self-esteem preferred portion controlled snack items because they believed that they lacked the self-control to regulate their own eating.

A consumer exhibits attachment to an object to the extent that it is used to maintain his or her self-concept. Objects can act as a ‘‘security blanket’’ by reinforcing people’s identities, especially in unfamiliar situations. For example, students who decorate their dorm rooms with personal items are less likely to drop out of college. This coping process may protect the self from being diluted in a strange environment. Products, especially those that serve as status symbols, also can play a pivotal role in impression management strategies as consumers attempt to influence how others think of them. Despite the adage, ‘‘You can’t judge a book by its cover,’’ in reality people often do.

The use of consumption information to define the self is especially important when an identity is yet to be adequately formed, as occurs when a person plays a new or unfamiliar role. Symbolic self-completion theory suggests that people who have an incomplete self-definition tend to bolster this identity by acquiring and displaying symbols associated with it. For example, adolescent boys may use ‘‘macho’’ products, such as cars and cigarettes, to augment their developing masculinity; these items act as a ‘‘social crutch’’ during periods of self-uncertainty.

Self-image congruence models assume a process of cognitive matching between product attributes and the consumer’s self-image. Research tends to support the idea of congruence between product use and self-image. One of the earliest studies to examine this process found that car owners’ ratings of themselves tended to match their perceptions of their cars; for example, Pontiac drivers saw themselves as more active and flashy than Volkswagen drivers saw themselves. Some specific attributes useful in describing matches between consumers and products include rugged/delicate, excitable/calm, rational/emotional, and formal/informal.

2. Consumers As Decision Makers

Traditionally, consumer researchers have approached decision making from a rational perspective. In this view, consumers calmly and carefully integrate as much information as possible with what they already know about a product, weigh the pluses and minuses of each alternative painstakingly, and arrive at satisfactory decisions.

2.1. Stages in the Decision-Making Process

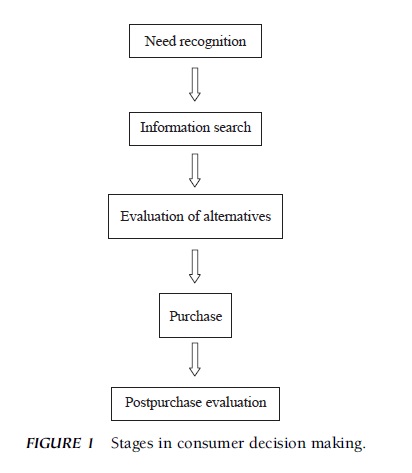

This process implies that marketing managers should carefully study the stages in decision making shown in Fig. 1 to understand how product information is obtained, how beliefs are formed, and what product choice criteria are specified by consumers. This knowledge will enable them to develop products that emphasize appropriate attributes and to tailor promotional strategies to deliver the types of information most likely to be desired in the most effective formats.

2.1.1. Need Recognition

The decision-making process begins with the stage of need recognition, when the consumer experiences a significant difference between his or her current state of affairs and some desired state. A person who unexpectedly runs out of gas on the highway recognizes a need, as does the person who becomes dissatisfied with the image of his or her car even though there is nothing mechanically wrong with it.

FIGURE 1 Stages in consumer decision making.

FIGURE 1 Stages in consumer decision making.

Once a need has been activated, there is a state of tension that drives the consumer to attempt to reduce or eliminate the need. This need may be utilitarian (i.e., a desire to achieve some functional or practical benefit, e.g., when a person loads up on green vegetables for nutritional reasons), or it may be hedonic (i.e., an experiential need involving emotional responses or fantasies, e.g., when a consumer thinks longingly about a juicy steak). Marketers strive to create products and services that will provide the desired benefits and permit the consumer to reduce this tension. This reduction is reinforcing, making it more likely that the consumer will seek the same path the next time the need is recognized.

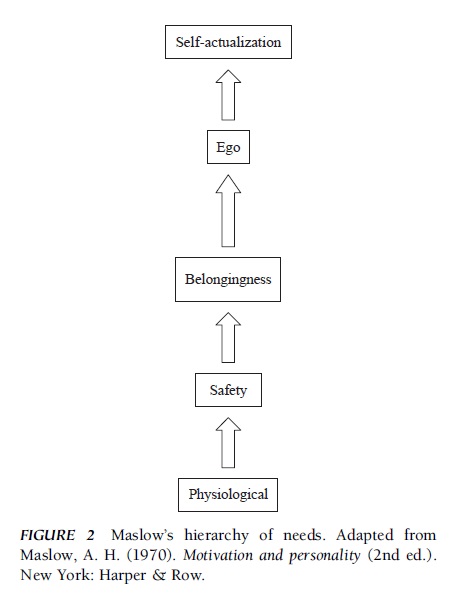

Maslow’s hierarchy of biogenic and psychogenic needs specifies certain levels of motives. This hierarchical approach, shown in Fig. 2, implies that one level must be attained before the next higher one is activated. Marketers have embraced this perspective because it (indirectly) specifies certain types of product benefits that people might be looking for, depending on the various stages in their development and/or their environmental conditions.

2.1.2. Information Search

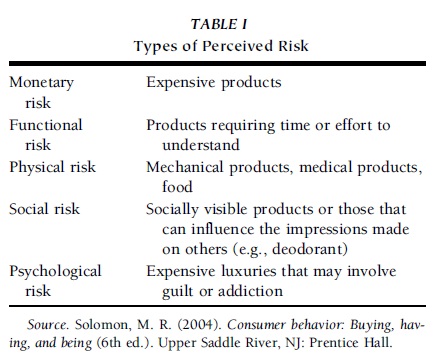

Need recognition prompts information search, that is, a scan of the environment to identify the options available to satisfy the need. As a rule, purchase decisions that involve extensive search also entail perceived risk, that is, the belief that a poor choice will produce potentially negative consequences. As shown in Table I, perceived risk may be a factor if the product is expensive, complex, and hard to understand or if the consumer believes that the product will not work as promised and/or could pose a safety risk. Alternatively, perceived risk can be present when a product choice is visible to others and the consumer runs the risk of social embarrassment if the wrong choice is made.

2.1.3. Evaluation of Alternatives

Information search yields a set of alternative solutions to satisfy the need. Those identified constitute the consumer’s evoked set. How does a consumer decide which criteria are important, and how does he or she narrow down product alternatives to an acceptable number and eventually choose one instead of others? The answer varies depending on the decision-making process used. A consumer engaged in extended problem solving may carefully evaluate several brands, whereas someone making a habitual decision might not consider any alternatives to his or her normal brand. Variety seeking, or the desire to choose new alternatives over more familiar ones, can also play a role; consumers at times are willing to trade enjoyment for variety because the unpredictability itself is rewarding.

TABLE I Types of Perceived Risk

TABLE I Types of Perceived Risk

FIGURE 2 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Adapted from Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

FIGURE 2 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Adapted from Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Evaluative criteria are the dimensions used to judge the merits of competing options. If all brands being considered rate equally well on one attribute (e.g., if all televisions come with remote control), consumers will have to find other reasons to choose one over the others. Determinant attributes are the characteristics actually used to differentiate among choices. For example, consumer research by Church & Dwight Company indicated that many consumers view the use of natural ingredients as a determinant attribute when selecting personal care products. This prompted the firm to develop toothpaste made from baking soda, an ingredient that the company already manufactured for its Arm & Hammer brand.

2.1.4. Purchase

Once a need has been recognized, a set of feasible options (often competing brands) that will satisfy the need have been identified, and each of these options has been evaluated, the ‘‘moment of truth’’ arrives: The consumer must make a choice and actually procure the product or service. However, other factors at the time of purchase may influence this decision. A consumption situation is defined by factors beyond characteristics of the product that influence a purchase decision. These factors can be behavioral (e.g., entertaining friends) or perceptual (e.g., being depressed, feeling pressed for time).

A consumer’s mood can have a big impact on purchase decisions. For example, stress can impair information-processing and problem-solving abilities. The two dimensions of pleasure and arousal determine whether a shopper will react positively or negatively to a consumption situation. In addition, the act of shopping itself often produces psychological outcomes ranging from frustration to gratification or even exhilaration.

Despite all of their efforts to ‘‘pre-sell’’ consumers through advertising, marketers increasingly recognize that many purchases are strongly influenced by the purchasing environment. Indeed, researchers estimate that shoppers decide on approximately two of every three products while wheeling their carts through supermarket aisles. Dimensions of the physical environment, such as decor, ambient sounds or music, and even temperature, can influence consumption significantly. One study even found that pumping in certain odors in a Las Vegas casino actually increased the amount of money that patrons fed into slot machines. Time is another important situational variable. Common sense dictates that more careful information search and deliberation occurs when consumers have the luxury of taking their time.

2.1.5. Postpurchase Evaluation and Satisfaction

Consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction (CS/D) refers to the attitude that a person has about a product after it has been purchased. This attitude, in turn, is an important determinant of whether the item will be bought again in the future. Despite evidence that customer satisfaction is steadily declining in many industries, marketers are constantly on the lookout for sources of dissatisfaction. For example, United Airlines’ advertising agency set out to identify specific aspects of air travel that contributed to discontent during the travel experience. The agency gave frequent fliers crayons and a map showing different stages in a long-distance trip and asked passengers to fill in colors using hot hues to symbolize areas causing stress and anger and using cool colors for parts of the trip associated with satisfaction and calm feelings. Although jet cabins tended to be filled in with a serene aqua color, ticket counters were colored orange and terminal waiting areas were colored fire red. This research led the airline to focus more on overall operations instead of just on in-flight experiences, and the ‘‘United Rising’’ advertising campaign was born.

Satisfaction is not determined solely by the actual performance quality of a product or service. It is also influenced by prior expectations regarding the level of quality. According to the expectancy disconfirmation model, consumers form beliefs about product performance based on prior experience with the product and/or communications about the product that imply a certain level of quality. When something performs the way in which consumers thought it would, they might not think much about it. If, on the other hand, the product fails to live up to expectations (even if those expectations are unrealistic), negative affect may result. If performance happens to exceed their expectations, consumers are satisfied and pleased. This explains why companies sometimes try to ‘‘underpromise’’ what they can actually deliver.

2.2. Biases in the Decision-Making Process

Although the rational model of decision making is compelling, many researchers now recognize that decision makers actually possess a repertoire of strategies— and not all of these strategies are necessarily rational. The constructive processing perspective argues that a consumer evaluates the effort required to make a particular choice and then chooses a strategy best suited to the level of effort required.

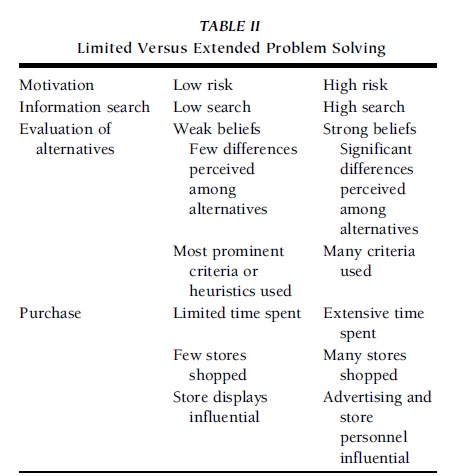

As shown in Table II, some purchases are made under conditions of low involvement, where the consumer is not willing to invest a lot of cognitive effort. Instead, the consumer’s decision is a learned response to environmental cues, for example, when he or she impulsively decides to buy something that is promoted as a ‘‘surprise special’’ in a store. In other cases, the consumer is highly involved in a decision, and again the stages of rational information processing might not capture the process. For example, the traditional approach is hard-pressed to explain a person’s choice of art, music, or even a spouse. In these cases, no single quality may be the determining factor. Instead, an experiential perspective stresses the Gestalt, or totality, of the product or service.

TABLE II Limited Versus Extended Problem Solving

TABLE II Limited Versus Extended Problem Solving

Consumption at the low end of involvement typically is characterized by inertia, where decisions are made out of habit because the consumer lacks the motivation to consider alternatives. Many people tend to buy the same brand nearly every time they go to the store. A competitor who is trying to change a buying pattern based on inertia often can do so rather easily because little resistance to brand switching will be encountered if the right incentive is offered.

At the high end of involvement, one can expect to find the type of passionate intensity that is reserved for people and objects that carry great meaning for the individual. When consumers are truly involved with a product, an ad, or a Web site, they enter a flow state. Flow is an optimal experience characterized by a sense of playfulness, a feeling of being in control, highly focused attention, and a distorted sense of time.

Especially when limited problem solving occurs prior to making a choice, consumers often fall back on heuristics, that is, mental rules-of-thumb that lead to a speedy decision. These rules range from the very general (e.g., ‘‘Higher priced products are higher quality products,’’ ‘‘Buy the same brand I bought last time’’) to the very specific (e.g., ‘‘Buy Domino, the brand of sugar my mother always bought’’).

One frequently used shortcut is the tendency to infer hidden dimensions of products from observable attributes. These are known as product signals. Country of origin is an example of a commonly used product signal. In some cases, people may assume that a product made overseas is of better quality (e.g., cameras, cars), whereas in other cases, the knowledge that a product has been imported tends to lower perceptions of product quality (e.g., apparel). Price is also a heuristic; all things equal, people often assume that ‘‘Brand A’’ is of higher quality simply because it costs more than ‘‘Brand B.’’

A well-known brand also frequently functions as a heuristic. People form preferences for a favorite brand and then literally might never change their minds in the course of a lifetime. In contrast to inertia, brand loyalty is a form of repeat purchasing behavior reflecting a conscious decision to continue buying the same brand. Purchase decisions based on brand loyalty also become habitual over time, although in these cases the underlying commitment to the product is much more firm. Because of the emotional bonds that can come about between brand-loyal consumers and products, ‘‘true blue’’ users react more vehemently when these products are altered, redesigned, or eliminated. For example, when Coca-Cola replaced its tried-and-true formula with New Coke during the 1980s, the company encountered a firestorm of national call-in campaigns, boycotts, and other protests.

Finally, many of people’s reactions to products are based on aesthetic responses to colors, shapes, and objects. Many of these preferences are deep-seated or culturally determined. Package designs often incorporate extensive research regarding consumers’ interpretations of the meanings accorded to symbols on the box or can. These meanings may be subtle or blatant, but they can exert a powerful effect on expectations about the product within the box or can. In one study, respondents rated the taste of a beer as heavier and more robust when it was served in a brown glass bottle than when the same product was dispensed in a clear bottle.

2.3. ‘‘Irrational’’ Decision Making

Psychologists have identified many cognitive mechanisms that interfere with ‘‘objective’’ information processing and decision making. Other researchers have gone a step further in their focus on domains of consumer behavior that cannot be readily explained by a cognitive perspective or where an individual’s actions are actually irrational and perhaps even dysfunctional. Indeed, some of consumers’ buying behaviors do not seem rational at all because they do not serve a logical purpose (e.g., collectors who pay large sums of money for paraphernalia formerly owned by rock stars). Other actions occur with virtually no advance planning at all (e.g., impulsively grabbing a tempting candy bar from the rack while waiting to pay for groceries).

Still other consumer behaviors, such as excessive eating, excessive drinking, and cigarette smoking, are actually harmful to the individual. These actions may be facilitated by many psychological factors, including the desire to conform to the expectations of others, learned responses to environmental cues, and observational learning prompted by exposure to media. The cultural emphasis on wealth as an indicator of self-worth may encourage activities such as shoplifting and insurance fraud. Exposure to unattainable ideals of beauty and success in advertising can create dissatisfaction with the self, sometimes resulting in eating disorders or self-mutilation.

Consumer addiction is a physiological and/or psychological dependence on products or services. Although most people equate addiction with drugs, virtually any product or service can be the focus of psychological dependence; for example, there is even a support group for Chap Stick addicts. Some psychologists are now voicing strong concerns about ‘‘Internet addiction,’’ a condition whereby Web surfers become obsessed by online chat rooms to the point where their ‘‘virtual’’ lives take priority over their real ones. Compulsive consumption refers to repetitive excessive shopping that serves as an antidote to tension, anxiety, depression, or boredom.

3. Psychological Influences On Consumption

The business process of market segmentation identifies groups of consumers who are similar to one another in one or more ways and then devises marketing strategies that appeal to the needs of one or more of these groups. One very common way in which to segment consumers is along demographic dimensions such as the following:

Age. People who belong to the same age group tend to share a set of values and common cultural experiences that they carry throughout life.

Gender. Many products are sex typed, and consumers often associate them with one gender or the other. Marketers typically develop a product to appeal to one gender or the other. For example, Crest’s Rejuvenating Effects toothpaste, made specifically for women, is packaged in a teal tube nestled inside a glimmering ‘‘pearlescent’’ box.

Social class and income. Working-class consumers tend to evaluate products in more utilitarian terms such as sturdiness and comfort. They are less likely to experiment with new products or styles such as modern furniture and colored appliances. Higher classes tend to focus on more long-term goals such as saving for college tuition and retirement.

Family structure. People’s family and marital status influences their spending priorities. For example, young bachelors and newlyweds are the most likely to exercise, consume alcohol, and go to bars, concerts, and movies.

Race and ethnicity. Ethnic minorities in the United States spend more than $600 billion per year on products and services, so firms must devise products and communications strategies tailored to the needs of these subcultures. Sometimes these differences are subtle yet important. When Coffee-Mate discovered that African Americans tend to drink their coffee with sugar and cream more so than do Caucasians, the company mounted a promotional blitz in black-oriented media that resulted in double-digit increases in sales volume.

Geography. Place of residence influences preferences within many product categories, from entertainment to favorite cars, decorating styles, or leisure activities. For example, BMW found that drivers in France prized its cars for their road-handling abilities and the self-confidence this gave them, whereas drivers in Austria were more interested in the status aspect of the BMW brand.

3.1. Psychographics and Lifestyles

Although these segmentation variables are very important, consumers can share the same demographic characteristics and still be very different people. Psychographics are data about people’s attitudes, interests, and opinions (AIOs) that allow marketers to cluster consumers into similar groups based on lifestyles and shared personality traits.

Lifestyle refers to a pattern of consumption reflecting a person’s choices of how he or she spends time and money. In an economic sense, a person’s lifestyle represents the way in which he or she has elected to allocate income in terms of relative allocations to various products and services and to specific alternatives within these categories. Lifestyle, however, is more than the allocation of discretionary income; it is a statement about who a person is in society and who the person is not. Group identities, whether of hobbyists, athletes, or drug users, gel around forms of expressive symbolism.

3.2. Personality Theory Applications to Consumer Behavior

A consumer’s personality, or unique psychological makeup, may influence the products and marketing messages that he or she prefers. Consumer psychologists have adapted insights from major personality theorists to explain people’s consumption choices.

3.2.1. Freudian Theory

Freudian psychology exerted a significant influence on applied consumer research, especially during the early days of the discipline. Freud’s writings highlight the potential importance of unconscious motives underlying purchases. This perspective also hints at the possibility that the ego relies on the symbolism in products to compromise between the demands of the id and the prohibitions of the superego. During the 1950s, motivational researchers attempted to apply Freudian ideas to understand the deeper meanings of products and advertisements. For example, for many years, Esso (now Exxon) reminded consumers to ‘‘Put a Tiger in Your Tank’’ after researchers found that people responded well to this powerful animal symbolism containing vaguely sexual undertones.

3.2.2. Jungian Theory

Freud’s disciple, Jung, introduced the concept of the collective unconscious, that is, a storehouse of memories inherited from a person’s ancestral past. These shared memories create archetypes, that is, universally shared ideas and behavior patterns involving themes such as birth, death, and the devil, that frequently appear in myths, stories, and dreams. For example, some of the archetypes identified by Jung and his followers include the ‘‘old wise man’’ and the ‘‘earth mother,’’ and these images appear frequently in marketing messages that use characters such as wizards, revered teachers, and even Mother Nature.

3.2.3. Trait Theory

Trait theory focuses on the quantitative measurement of personality traits, that is, identifiable characteristics that define a person. Some specific traits relevant to consumer behavior include innovativeness (i.e., the degree to which a person likes to try new things), materialism (i.e., the amount of emphasis placed on acquiring and owning products), self-consciousness (i.e., the degree to which a person deliberately monitors and controls the image of the self that is projected to others), need for cognition (i.e., the degree to which a person likes to think about things and, by extension, expend the necessary effort to process brand information), and self-monitoring (i.e., the degree to which a person is concerned with the impression that his or her behaviors make on others).

4. Cultural And Interpersonal Influences On Consumption

Values are very general ideas about good and bad goals, and these priorities typically are culturally determined. From these flow norms, that is, rules dictating what is right or wrong and what is acceptable or unacceptable. Consumers purchase many products and services because they believe that these products will help them to attain value-related goals. For example, an emphasis on personal hygiene in Japan has created a demand for products such as automated teller machines (ATMs) that literally ‘‘launder’’ money by sanitizing yen before dispensing them to bank customers.

4.1. Subcultures and Reference Groups

Members of a subculture share beliefs and common experiences that set them apart from others in the larger culture. Whether ‘‘Dead Heads’’ or ‘‘Skinheads,’’ each group exhibits its own unique set of norms, vocabulary, and product insignias (e.g., the skull and roses that signifies the Grateful Dead subculture).

A reference group is an actual or imaginary individual or group that influences an individual’s evaluations, aspirations, or behavior. As a rule, reference group effects are more robust for purchases that are (a) luxuries (e.g., sailboats) rather than necessities and (b) socially conspicuous or visible to others (e.g., living room furniture, clothing).

4.2. Opinion Leaders

An opinion leader is a person who is frequently able to influence others’ attitudes or behaviors. Opinion leaders are extremely valuable information sources because (a) they are technically competent and, thus, more credible; (b) they have prescreened, evaluated, and synthesized product information in an unbiased way; and (c) they tend to be socially active and highly interconnected in their communities.

4.3. Diffusion of Innovations

Diffusion of innovations refers to the process whereby a new product, service, or idea spreads through a population. If an innovation is successful (most are not), it typically is initially bought or used by only a few people. Then, more and more consumers decide to adopt it until it might seem (sometimes) that nearly everyone has bought or tried the innovation.

A consumer’s adoption of an innovation resembles the standard decision-making sequence whereby he or she moves through the stages of awareness, information search, evaluation, trial, and adoption. The relative importance of each stage may differ depending on how much is already known about the innovation as well as on cultural factors that may affect people’s willingness to try new things. However, even within the same culture, not all people adopt an innovation at the same rate. Some do so quite rapidly, whereas others never do at all. Consumers can be placed into approximate categories based on their likelihood of adopting an innovation. Roughly one-sixth of the people are very quick to adopt new products (i.e., innovators and early adopters), and one-sixth of the people are very slow (i.e., laggards). The other two-thirds are somewhere in the middle (i.e., late adopters). These latter consumers are the mainstream public; they are interested in new things, but they do not want them to be too new.

Even though innovators represent only approximately 2.5% of the population, marketers are always interested in identifying them. Innovators are the brave souls who are always on the lookout for novel developments and who will be the first to try new offerings. They tend to have more favorable attitudes toward taking risks, have higher educational and income levels, and be socially active. In addition, many innovators also are opinion leaders, so their acceptance of an innovation may be a crucial factor in persuading others to try it as well.

As a rule, consumers are less likely to adapt innovations that demand radical behavior changes—unless they are convinced that the effort will be worthwhile. As a result, evolutionary changes (e.g., a cinnamon version of Quaker oatmeal) are more likely to be rapidly adapted than are revolutionary changes (e.g., ready-to-eat microwaveable Quaker oatmeal). The following factors make it more likely that consumers will accept an innovation:

- Compatibility with current lifestyle

- Ability to try the product before buying

- Simplicity of use

- Ease of observing others using the innovation

- Relative advantage over benefits offered by other alternatives

References:

- Alba, J. W., & Hutchinson, J. W. (1988). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 411–454.

- Baumgartner, H. (2002). Toward a personology of the consumer. Journal of Consumer Research, 29, 286–292.

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 139–168.

- Belk, R. W., Wallendorf, M., & Sherry, J. F., Jr. (1989). The sacred and the profane in consumer behavior: Theodicy on the odyssey. Journal of Consumer Research, 16, 1–38.

- Bettman, J. R., Luce, M. F., & Payne, J. W. (1988). Constructive consumer choice processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 187–217.

- Bettman, J. R., & Park, C. W. (1980). Effects of prior knowledge and experience and phase of the choice process on consumer decision processes: A protocol analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 7, 234–248.

- Cialdini, R. B. (1993). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: William Morrow.

- Dichter, E. (1964). The handbook of consumer motivations. New York: McGraw–Hill.

- Fournier, S. (1998). Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 343–373.

- Hoffman, D. L., & Novak, T. P. (1996). Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations. Journal of Marketing, 60, 50–68.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 132–140.

- Jacoby, J., & Chestnut, R. (1978). Brand loyalty: Measurement and management. New York: John Wiley.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

- Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

- Midgley, D. F. (1983). Patterns of interpersonal information seeking for the purchase of a symbolic product. Journal of Marketing Research, 20, 74–83.

- Oliver, R. L. (1996). Satisfaction. New York: McGraw–Hill.

- Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Schumann, D. (1983). Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. Journal of Consumer Research, 10, 135–146.

- Ratner, R. K., Kahn, B. E., & Kahneman, D. (1999). Choosing less-preferred experiences for the sake of variety. Journal of Consumer Research, 26, 1–15.

- Robertson, T. S., & Kassarjian, H. H. (Eds.). (1991). Handbook of consumer behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Rogers, E. M. (1983). Diffusion of innovations (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press.

- Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: Free Press.

- Sirgy, M. J. (1982). Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 287–300.

- Solomon, M. R. (1983). The role of products as social stimuli: A symbolic interactionism perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 10, 319–329.

- Solomon, M. R. (2004). Consumer behavior: Buying, having, and being (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Snyder, M. (1979). Self-monitoring processes. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 85–128). New York: Academic Press.

- Thaler, R. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4, 199–214.

- Wells, W. D., & Tigert, D. J. (1971). Activities, interests, and opinions. Journal of Advertising Research, 11, 27.

- Wicklund, R. A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1982). Symbolic self-completion. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Wright, P. (2002). Marketplace metacognition and social intelligence. Journal of Consumer Research, 28, 677–682.

- Zablocki, B. D., & Kanter, R. M. (1976). The differentiation of life-styles. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 269–297.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.