This sample Classical Conditioning Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of psychology research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Abstract

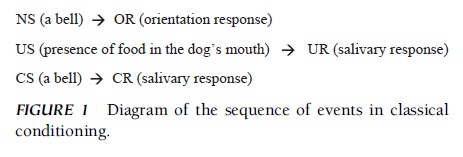

The simplest associative mechanism, whereby organisms learn to produce new responses to stimuli and learn about relations between stimuli or events, is classical, or Pavlovian, conditioning. In classical conditioning, a neutral stimulus is repeatedly paired with another stimulus, called an unconditioned stimulus (US), that naturally elicits a certain response, called an unconditioned response (UR). After repeated trials, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS) and evokes the same or a similar response, now called the conditioned response (CR). Most of the concepts presented in this research paper were developed by Pavlov. However, it also examines how original classical conditioning has been modified. Although the basic conditioning paradigm emerged 100 years ago, its comprehension and conceptualization are still developing.

Outline

- From Pavlov to the Present

- Basic Conditioning Procedure

- Basic Processes

- Experimental Procedures

- Excitatory Conditioning

- Inhibitory Conditioning

- What Influences Classical Conditioning?

- Applications

1. From Pavlov To The Present

Russian physiologist I. Pavlov (1849–1936) was one of the pioneers in research on classical conditioning. His investigations, carried out at the end of the 19th century, form the axis of associative learning. Pavlov was interested in the digestive system and, through these studies, he observed that dogs, the subjects of his experiments, anticipated the salivation response when they saw food. Subsequently, Pavlov presented a light or the ticking of a metronome [conditioned stimulus (CS)] for a number of seconds before the delivery of food [unconditioned stimulus (US)]. At first, the animal would show little reaction to the light but, as conditioning progressed, the dog salivated during the CS even when no food was delivered. This response was defined as the conditioned response. Hence, research on classical conditioning began. Soviet psychology has changed in many ways since the death of Pavlov in 1936, and many of these changes brought it closer to American psychology. One way in which the general theory of Pavlovian conditioning developed similarly in the two countries was via the incorporation of cognitive variables. The originally simple Pavlovian paradigm was expanded and reinterpreted through the efforts of many American researchers. American learning theorists developed alternative methods for estimating the strength of the association between a CS and a US. They also identified new Pavlovian phenomena and suggested new explanations of the basic mechanisms underlying the conditioning produced by use of Pavlovian procedures. Although Pavlov’s writings were widely disseminated in the United States, most of the criticism of his ideas was expressed in 1950 by J. A. Konorski in Poland. Konorski and Miller, Polish physiologists, began the first cognitive analysis of classical conditioning, the forerunner of the work by R. A. Rescorla and A. R. Wagner (American psychologists) and A. Dickinson and H. J. Mackintosh (English psychologists).

In the 1950s, some clinical psychologists—such as J. Wolpe (in South Africa), H. J. Eysenck (in the United Kingdom), and B. F. Skinner (in the United States)—began to treat psychological disorders with a technology based on learning principles, aiming to substitute pathological behavior for a normal one. This movement, known as behavior modification, was based on both classical and operant conditioning and reinforced the popularity of these techniques among clinicians.

Significant changes on theoretical views upon this phenomenon were introduced by Rescorla and Wagner in 1972, whose model assumed that organisms, in their interaction with the environment, form causal expectations that allow them to predict relations between events. From this perspective, learning would consist of the acquisition of information about the causal organization of the environment. In order to acquire this information, associations between elements are established. However, it is not sufficient for the elements to be contiguous so that an animal will associate them, as Pavlov proposed; it is also necessary for the elements to provide information about a causal relation. In fact, the central concept is the notion of contingency and the way in which it is represented in the animal’s mind. This new ‘‘cognitive associationism’’ accepted the existence of both cognitive processes and associative mechanisms in the mind and rapidly gained wide support among learning experimentalists.

Although in some cases the organism seems to be conditioned only on grounds of CS–US ‘‘contiguity,’’ in many other cases learning seems to allow the organism to predict US arrival from the CS appearance; this would be due to a ‘‘contingency relationship’’ that is expressed in terms of probability; if the probability of the appearance of the US is the same in the presence and in the absence of the CS, contingency will be null and no conditioning will occur. On the contrary, if the probability of the US appearing in the presence of the CS is greater than the probability of it appearing without the CS, then conditioning occurs. Therefore, classical conditioning is defined as the capacity of organisms to detect and learn about the predictive relation between signals and important events. Currently, classical conditioning is not considered to be simple and automatic learning about the establishment of CS–US relations but rather a complex process in which numerous responses intervene, not just glandular and visceral responses, as was thought at first. It also depends on the relevance of the CS and the US, the presence of other stimuli during conditioning, how surprising the US may be, and other variables.

Lastly, the growth of connectionist modeling has renewed interest in classical conditioning as a fruitful method for studying associative learning.

2. Basic Conditioning Procedure

The procedure of classical conditioning consists of the repeated presentation of two stimuli in temporal contiguity. First, a neutral stimulus (NS) is presented— that is, a stimulus that does not elicit regular responses or responses similar to the unconditioned response (UR). Immediately after that, the US is presented.

FIGURE 1 Diagram of the sequence of events in classical conditioning.

FIGURE 1 Diagram of the sequence of events in classical conditioning.

Because of this pairing, the NS will become a CS and, therefore, will be capable of provoking a conditioned response (CR) similar to the UR that, initially, only the US could elicit (Fig. 1).

On the initial trials, only the US will elicit the salivation response. However, as the conditioning trials continue, the dog will begin to salivate as soon as the CS is presented. In salivary conditioning, the CR and the UR are both salivation. However, in many other conditioning situations, the CR is very different from the UR. According to Pavlov, the animals learn the connection between stimulus and response (CS–UR). Currently, it is understood that animals learn the connection between stimuli.

3. Basic Processes

Some basic processes that affect all sorts of conditioning learning have been identified. They include the following:

- Acquisition: the gradual increase in strength of CR, linking the two stimuli (CS followed by the US).

- Extinction: the reduction and eventual disappearance of the CR at the CS onset, after repeated presentations of CS without being followed by US.

- Generalization: when a CR is linked to a CS, the same CR is elicited by other CSs in proportion to their similarity to the original CS.

- Discrimination: occurs when subjects have been trained to respond in the presence of one stimulus but not in the presence of another.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1. Appetitive Conditioning

Appetitive conditioning is a modality in which the US (and CS) will originate a positive (approaching, consummative) behavior in the organism.

4.2. Aversive Conditioning

In aversive conditioning, the US and CS have negative properties and will generate an escape or evitation behavior. Aversion to some taste (Garcia effect) showed the possibility of obtaining long aversive reactions to some CS taste that, after being linked to some US with strong aversive digestive qualities, would generate an evitation response after a long interstimuli interval. Learning taste aversion plays an essential role in the selection of food because it prevents the ingestion of toxic foods. It has also helped to understand and treat food aversions in people suffering from cancer and undergoing chemotherapy.

5. Excitatory Conditioning

Excitatory conditioning occurs because the CS allows the subject to predict when the US will occur. In excitatory conditioning, there is a positive relation between the CS and the US. The excitatory stimulus (CS+) becomes a stimulus that elicits a CR after its association with the US. Traditionally, classical conditioning research has focused on this kind of conditioning.

6. Inhibitory Conditioning

Inhibitory conditioning occurs because the CS allows the subject to predict that no US will be presented; that is, an inhibitory conditioned stimulus (CS-) signals the absence of an unconditioned stimulus (either positive or aversive), provoking the inhibition of the CR in the organism. This kind of conditioning was studied by Pavlov, and there has been a renewed interest that continues today.

One of the clearest examples of this procedure is the one presented by M. Domjan: A red traffic light (CS+) signals the potential danger (US), which is the car. If a policeman indicates that we can cross the street (CS-) despite the red light, he is signaling that there is no danger (US). Inhibitory stimuli, such as ‘‘out of order’’ or ‘‘do not cross’’ signs, provide useful information.

7. What Influences Classical Conditioning?

The capacity of stimuli to become associated is modified by many phenomena, such as the CS–US interval, spatial contiguity between stimuli, the similarity of the CS and the US, the intertrial interval, the characteristics of the CS and the US (intensity, novelty, and duration), or previous experience of the CS (latent inhibition), the simultaneous presence of other more salient stimuli (overshadowing), or more informative stimuli (blocking).

7.1. CS–US Interval

The interstimulus interval is the time between the appearance of the CS and the appearance of the US. It is one of the critical factors that determine the development of conditioning. Different CS–US interstimulus intervals are usually employed.

Simultaneous conditioning describes the situation in which the CS and the US begin at the same time. Delayed conditioning occurs when the onset of the CS precedes the US onset. Trace conditioning occurs when the CS and US are separated by some interval in which neither of them is present. The US is not presented until after the CS has ended. Backward conditioning occurs when the CS is presented after the US. This procedure casts doubt on the principle of stimulus contiguity because although the CS and the US are presented in inverse order, the association should be equally efficient.

The simultaneous and backward conditioning procedures produce poorer conditioning in comparison to delayed and trace procedures. However, today, due to the use of more sophisticated measurements than those traditionally employed, all the procedures can produce efficient conditioning.

8. Applications

Classical conditioning is relevant to behavior outside the laboratory in daily life and plays a key role in understanding the origins and treatment of clinical disorders. In humans, classical conditioning can account for such complex phenomena as an individual’s emotional reaction to a particular song or perfume based on a past experience with which it is associated; the song or perfume is a CS that elicits a pleasant emotional response because it was associated with a friend in the past. Classical conditioning is also involved in many different types of fears or phobias, which can occur through generalization.

Pioneering work on this type of phenomena was carried out by J. B. Watson and collaborators in the 1920s. They were able to condition a generalized phobia to animals and a white furry object in a young child, ‘‘Albert’’ (creating a learned neurotic reaction), and also to extinguish a phobia in another child, ‘‘Peter,’’ through a learning procedure (carried out by Mary C. Jones). Both cases have been considered pioneering work in the behavior modification field.

8.1. Everyday Human Behavior

8.1.1. Classical Conditioning and Emotional Response

Recent reanalyses have evidenced the relevance of individual differences and cognitive variables. People who are more anxious in general develop phobias from experiences that do not produce fear in others.

Fears can be learned by multiple means that include direct Pavlovian conditioning, but the Pavlovian paradigm, with the revisions of the neoconditioning theory, continues to be one of the most influential theories on phobic anxiety. All fears or phobias do not seem to be explainable by simple Pavlovian conditioning, although many may be. Many phobias are reported to be the result of indirect or cognitive learning, including learning by observation and by information transfer. Classical conditioning has also been useful to explain panic attacks.

8.1.2. Classical Conditioning and Food Aversion

Food aversions are a serious clinical problem, especially those developed by association with the nausea produced by chemotherapy for cancer, which may later interfere with eating many foods. Applying modern knowledge of the classical conditioning process, treatment usually consists of trying to prevent the aversion by minimizing the predictability relationship of the CS and the US (nausea). Giving the patients a food with a highly salient, novel taste in novel surroundings results in blocking, and the novel cues overshadow the tastes of more familiar foods. The result is a strong aversion to cues that will not be present after chemotherapy is finished. This is helpful and causes no problems because there is little development of conditioned nausea to familiar foods when eaten at home.

8.2. Clinical Treatment

Behavior therapy, based on the principles of classical conditioning, has been used to eliminate or replace behavior, to eliminate the emotional responses of fear and anxiety, and as treatment for nocturnal enuresis, alcoholism, and so on.

8.2.1. Systematic Desensitization Therapy

As behavioral methods developed over time, a behavior therapy technique called systematic desensitization was devised based broadly on the classical conditioning model. Undesirable responses, such as phobic fear reactions, can be counterconditioned by the systematic desensitization technique. This technique inhibits expressions of fear by encouraging clients to face the feared CS and thus allowing extinction to occur. In systematic desensitization, anxiety is associated with a positive response, usually relaxation. Systematic desensitization is a procedure in which the patient is gradually exposed to the phobic object; training in progressive relaxation is an effective and efficient treatment for phobias.

8.2.2. Implosive (Flooding) Therapy

One approach to treating phobias with classical conditioning was originally called implosive therapy (flooding). It is used to extinguish the conditioned fear response by presenting the CS alone, repeatedly, and intensely. The phobic individual experiences the CS, and all the conditioned fear is elicited, but no aversive US follows, nothing bad happens to the subject in the presence of the CS, and so the conditioned fear of the CS disappears.

References:

- Chance, P. (2002). Learning and behavior (5th ed.). New York: Brooks/Cole.

- Davey, G. (Ed.) (1987). Cognitive processes and Pavlovian conditioning in humans. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Dickinson, A. (1980). Contemporary animal learning theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Domjan, M. (2000). Essentials of conditioning and learning (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson.

- Domjan, M. (2003). Principles of learning and behavior (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson.

- Klein, S. B. (2001). Learning: Principles and applications (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Leahey, T. H., & Harris, R. J. (2000). Learning and cognition (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Leslie, A. M. (2001). Learning: Association or computation? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(4), 124–127.

- Lieberman, D. A. (2000). Learning: behavior and cognition (3rd ed.). Pacific Grove: CA: Wadsworth.

- Mackintosh, N. J. (1983). Conditioning and associative learning. Oxford, UK: Clarendon.

- Mackintosh, N. J. (Ed.). (1994). Animal learning and cognition. New York: Academic Press.

- Mazur, J. E. (2002). Learning and behavior (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- O’Donohue, W. (1998). Learning and behaviour therapy. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes. London: Oxford University Press.

- Schwartz, B., Wasserman, E. A., & Robbins, S. J. (2002). Psychology of learning and behavior (5th ed.). New York: Norton.

- Rescorla, R. A., & Wagner, A. R. (1972). A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and non-reinforcement. In A. H. Black, & W. F. Prokasy (Eds.), Classical conditioning: II. Current research and theory. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to order a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.