This sample Active Euthanasia Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Abstract

In this research paper the focus is on euthanasia from a historical point of view, on classifications, and ethical issues. Significant space is reserved for the shaping of a practice of active euthanasia in three countries that as of 2015 have one, with extensive data on the Netherlands both before and after the law on euthanasia and on Belgium and Luxembourg after legalization.

Introduction

Active euthanasia generally has been a sensitive subject throughout history, with an overriding opposition mainly based on religious and medical professional arguments. Minority-based attempts at regulation in several countries in Europe and the USA can be observed since the nineteenth century. Public and medical professional debates centered on many different ethical arguments, all without empirical foundation. The Netherlands has been the first country recognizing the need for regulation of both an existing practice and patients’ rights for a self-chosen death, followed by Belgium and Luxembourg. Discussed are the shaping of this process, the roles of the profession, the courts and politics in realizing a regulated practice with safeguards, the review of each individual case, and the overall evaluations of the effect of the legalization of “active euthanasia.”

Concepts And Clarifications

The word euthanasia comes from the Greek word “euthanatos,” meaning a good death, “thanatos,” while the “eu” refers to a positive connotation. The word euthanasia has different meanings depending on the context, both in history and the present. A good death historically implied a quick death as “easy death,” without suffering that comes about without an intervention by someone else, even seen as a noble death. Additional elements in the definition have appeared over time:

- The notion that a good death can be brought about by ending the suffering of a person by someone else as the decisive element when the word “active” is added to the term euthanasia.

- It is the intention to end the life of that other person.

- The act is in the best interest of the suffering person.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) states suffering as a necessary condition, with “the painless killing of a patient suffering from an incurable and painful disease or in an irreversible coma.”

A problem in defining euthanasia is that the word covers too many different situations, being a source of confusion rather than clarification. Does the term apply only to adults or also children, does it cover active rather than passive euthanasia, and does it cover only competent but also incompetent (e.g., comatose) patients? There may be agreement on some situations and disagreement on others, making the term unworkable, because of the various associations.

The Dutch definition has limited the options to one: the act qualifies as euthanasia not only because it ends suffering but also insofar as there is a voluntary and well-considered request. According to the Dutch State Committee on Euthanasia (1985), euthanasia is the intentional ending of life by someone else than the person involved, after his request (Staatscommissie Euthanasie 1985). With this definition only what is called elsewhere “voluntary active euthanasia” qualifies as euthanasia. This definition has also been adopted in euthanasia laws in both Belgium and Luxembourg.

Classifications

Historically and in most actual discussions, euthanasia generally still is classified broadly and distinguished on the basis of action or omission, consent, and procedure. Distinctions on the basis of action (1) are active or passive; on the basis of consent/request (2), voluntary, nonvoluntary, or involuntary; and on the basis of procedure (3), direct or indirect.

- Active euthanasia is the intervention to end life intentionally, resulting in death. Passive euthanasia is a term reserved for two different medical situations. The first is not starting or discontinuing medical treatment that has no foreseeable benefit for a patient, as in a situation where physicians agree that continuing a treatment will not lead to a cure or an acceptable state of health for a patient. The second situation concerns a decision to treat a patient’s pain and symptoms of suffering with a pharmaceutical substance that alleviates this pain and these symptoms, but a degree of (un)certainty will lead to the death of this patient. In both examples causing the death of a patient is not primarily intended but nevertheless is the foreseeable most likely effect. One usually speaks in these cases of “allowing to or letting die” as opposed to “killing a patient.”

- Voluntary, nonvoluntary, or involuntary euthanasia

Voluntary euthanasia implies the consent or request of a patient; nonvoluntary euthanasia is the term used for active ending of life when there is no consent (possible) from a patient, due to the medical situation; and involuntary euthanasia is a term reserved for interventions to end life against the will of a patient.

- Direct or indirect euthanasia

Direct euthanasia is the term reserved for the intentional act to end life such as an injection; indirect euthanasia is the term reserved for interventions that result in death due to the cessation of medical treatments or the alleviation of signs and symptoms with the foreseeable effect of death. The definitions overlap and these latter distinctions usually do not have additional value.

The distinction between active and passive euthanasia still is a fundamental one for most physicians, lawyers, ethicists, and theologians. It can be found in almost all statements of medical societies all over the world, but not in statements of societies in countries that legally allow active euthanasia. There euthanasia is limited to the “voluntary active ending of life after a request.” But elsewhere this distinction has been codified in legal decisions, up to the US Supreme Court. Those who wish to maintain it usually tend to support passive euthanasia and oppose active euthanasia. However from early on in the modern debate on euthanasia in the past 40 years, it has been argued that the distinction is questionable.

In the first place, the term passive is experienced as mystifying, because a decision to remove life support remains an action on the part of a physician; even though a disease will be the cause of death, the intervention is an action of “an agent.”

Rachels, in a seminal article in 1975, was one of the first to question the validity of the distinction by pointing out that, for example, not allowing to die usually means prolonging suffering. In addition, he asserts that, at the level of a physician’s intentions, accepting death because it is the humane thing, the method used between letting die and killing in itself makes no moral difference (Rachels 1975). But the distinction still continues to “haunt” bioethics.

As stated, in the Netherlands a different course has been followed. After adopting the definition of euthanasia as an action that intends to end the life of someone at his explicit request, there has been some progress in clarifying these theoretical discussions on a correct terminology. The term euthanasia, elsewhere called “voluntary active euthanasia,” is reserved only for the procedure to end life after a request. Here as in some other Western countries, decisions to stop or not to start treatments are no longer classified as (passive) euthanasia, but called “death in the course of nontreatment decision (NTD).” Neither are medical decisions to treat patients with severe symptoms while foreseeing death also due to these treatments classified as (passive) euthanasia but “death in the course of alleviating pain and symptoms (APS).”

For the Dutch professions dealing with end-of-life issues, the conclusions allowing physician-assisted dying (PAD) apply both to (voluntary) euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide (PAS), a necessary addition since both euthanasia and assisting in suicide are prohibited in this country. The Dutch definition has also been adopted in the Belgian and Luxembourgian euthanasia laws.

What has become clear in the Dutch investigations of medical decisions at the end of life, the so-called MDELs, is that there remain two types of life-ending actions that are within the category of “euthanasia, active.” One is “euthanasia,” thus after a request, and the other is the action to end life without a request, described as life-ending action without explicit request, abbreviated as LAWER. These two types will be described in more detail.

Ethics

The ethical arguments pro or contra-active voluntary euthanasia in antiquity focus on the act to end suffering, irrespective whether a request has been made. Social arguments based on ideas of a person being a valuable member of the state play a significant role.

The international public debates in the nineteenth century show a wide variety of arguments that over time are surprisingly consistent and similar, seemingly not dependent on the advance of medical technology with its ability to prolong life, with the exception of one advance: the discovery of anesthetic agents as chloroform, ether, and morphine, even though the last one has been known and used for ages. The application of these agents in medical practice prompted a large response around the 1870s with the desire to be applied to alleviate suffering of incurably ill patients.

Attempts to “organize” the arguments for or against euthanasia have been helpful with the distinctions offered by Finns and Bacchetta (1995, pp. 563–568). They distinguish arguments of (1) deontology, based on principles of good or evil; (2) consequentialism, based on real or supposed consequences, including “slippery slope” arguments; and (3) clinical pragmatics, based on the effects on the doctor-patient relationship or health care as an institution.

1.1. Deontological arguments against euthanasia are, for example, the claim that life is sacred and God-given and has intrinsic value, without an option to end it. The end of life should be experienced because the end has lessons to be experienced and because suffering is God-given. Besides, there is a right to life that an individual cannot give up. A physician’s duty is and has always been to protect and preserve that life, not to terminate it.

1.2. Proponents however claim that euthanasia is a human right, based on the principle of self-determination. There is no duty to undergo not relievable suffering. Also, active euthanasia should follow from the right to refuse further life-prolonging medical treatment without hope for cure. In addition if suicide is morally defensible, then assisting in it is morally appropriate also.

2.1. Consequential arguments against euthanasia share a sense of distrust and fear. A central argument is fear for abuse of the practice and a “slippery slope” with respect to the acceptable indications. Allowing physician-assisted dying (PAD) will send a message to society of the devaluation of human life. Moreover, allowing ending the life of competent patients will be followed by accepting the ending of life of the nonterminally ill, the incompetent, and in general all vulnerable patients. Psychological and economical arguments will play an increasing role: allowing PAD will cause suffering to others. And assisted dying will be requested by patients feeling they are a burden, desiring to take away the strain on their families or by family interests in ending life, not the least for economic reasons of cost, especially when there is no or inadequate insurance. And physicians will give in to pressures of cost containment within an increasingly expensive health-care system.

2.2. Consequential arguments supporting euthanasia are the following. Allowing PAD will increase self-control and individual self-esteem. It will also increase public awareness of the need to decide in time for a chosen manner to die, especially when incompetence might be a possibility at the end of life. It will also provide a wider moral basis for human rights in society. It will enhance a morality that secures the personal and individual character in making decisions on death and dying.

3.1. Clinical pragmatic arguments against PAD are, for example, a claim that most deaths are not painful nor that physicians are unwilling to stop treatments and use adequate pain medication to effectively alleviate suffering; in short good medical/palliative care does not lead to a request for PAD. Besides that it is not always possible to predict with absolute certainty the inevitable outcome of death, resulting in ending the life of patients who could have continued a further full life.

Allowing or even legalizing PAD will be perceived as a threat by patients and lead to distrust of physicians and the system of health care. Besides that it is nearly impossible to establish the voluntariness and thus the authenticity of a request, especially because family influences are difficult to assess. And requesting PAD hardly seems the act of a rational human being since incurably ill patients often suffer from depression or have their minds clouded by the medications being used. The mere option of PAD may result in less willingness of families and physicians to care for their sick and old. Suggesting PAD itself may have the effect on patients that their suffering is futile and may erode their courage to fight against a disease.

3.2. Clinical pragmatic arguments in favor of PAD focus on limiting meaningless suffering. It is indicated only for patients who have terminal or chronic unbearable suffering. Allowing PAD means less risk for involuntary or no voluntary deaths. It means a greater sense of control for patients and less risk for suicide. A regulated practice with a focus on adequate palliative care, even for the poor or uninsured, would force institutions to provide adequate care before a request for PAD could be granted. The option of PAD increases the quality of dying, intensifies family relationships, and effects lower grief reactions in the surviving families and friends. Instead of distrust it enhances trust in the medical profession, because patients realize the emotional distress of euthanasia for physicians.

Data on the validity of ethical arguments either pro or contra-euthanasia are only available from research in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. So far there are no indications of a slippery slope or realization of other negative consequences that are feared in many of the ethical statements. There is some research on the positive consequences for patients and families with respect to grief and depression.

The Practice Of (Active) Euthanasia

Euthanasia in the sense of “an action to end a life after a request” has become accepted in three countries in the world: the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. The following is a brief account of the practice of euthanasia in each of these countries. The information on the Netherlands is more extensive in comparison to the other two countries since more information is available over a longer period of time.

The Netherlands

Fundamental for the Dutch development was lifting the taboo on admitting the existence of a veiled practice of euthanasia.

In comparison to other countries, not only political but other social developments have been important in the final outcome of a law, allowing physicians to end the life of their ill patients. In hindsight, this result was more the joint effect of public demand, pressure groups, the intention to self-regulate policies by the medical profession, and the supportive position of the courts, while the political machine trailed behind. Acceptable euthanasia in the Netherlands is the result of a “bottom-up” movement, rather than the result of top-down forced political decisions by parliamentary majorities, as in Belgium and Luxembourg.

Social Developments, The Courts, And The Medical Profession

Contrary to the USA, the UK, and Germany, there were no early public debates on euthanasia: there is no “history of or on euthanasia” of significance in this country. This debate in the Netherlands was part of a broader movement for changes in publicly shared convictions, morality, and power for individuals. This movement with a focus against paternalism and in favor of emancipation, authenticity, individual (patients’) rights, and self-determination or autonomy expressed itself also within the system of health care, opposing physician authority and the medicalization of life and death. The subject of truth telling at the sickbed was first on the agenda, followed by desires for “death with dignity.” Within medicine the technological possibilities to keep patients alive almost indefinitely forced physicians to come to terms with the limits of medical interventions and the wishes of individual extremely ill patients. This development in medicine led to what has been called “a veiled or hidden practice” of euthanasia, at that time also including the stopping of medically “meaningless” treatments, then still called “passive euthanasia.”

Courts

The courts in the Netherlands were instrumental in “decriminalizing” the issue of euthanasia, by recognizing a legitimate conflict of duties for physicians, allowing ending life without punishment, in a given situation. The courts were also instrumental in developing jurisprudential norms for acceptable euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide.

Starting with the landmark case of Mrs. Postma-van Boven, in the (lower) Court of Leeuwarden in 1974, the focus of the courts has not been on ending life as murder but on normal medical behavior at the end of life in case of unbearable suffering with illness, thus on “medical science and medical ethics.”

In three cases the Dutch Supreme Court set the tone for conducive policies. In the Schoonheim case (1984) the court’s message was the recognition of a conflict of duties, between the duty to protect life and also to alleviate suffering, legitimizing life-ending interventions in certain individual cases. A shared or communal aspect should be that the physician is in a situation of force majeure or emergency, not really having an easy choice. In the Chabot case (1994) the Supreme Court adopted the rule that the cause or the source of suffering, being either somatic, psychic, or otherwise, in itself should not be decisive, but rather the seriousness or depth of it.

With the Brongersma case (2002) the Supreme Court limited the supposedly liberal interpretation on the source of suffering by stipulating the principle of classification. Classification implies the necessary presence of a medically classified disease or illness as the cause of suffering. The assessment of suffering without such a source, as in “suffering of life without meaning,” is not deemed to be within the medical domain.

Medical Profession

The role of the medical professional society in the Netherlands, the KNMG, the Koninklijke Nederlandsche Maatschappij tot bevordering der Geneeskunst, in realizing transparent procedures for acceptable euthanasia is unique and can hardly be underestimated. From the early 1970s of the past century onward to this day, the society of medical professionals has taken steps to assure a legally safe and responsible practice for physicians who ended the lives of their patients while supporting and maintaining the criminal nature of the act in the Penal Code.

One line of thinking in the KNMG’s position has been that acts of euthanasia and assisted suicide are “not normal medicine,” that death has not been “natural,” and that the act should remain criminally punishable. Each act, as stated in the 1973 paper, should be reported and subject to judicial assessment.

Safeguards

From the start the KNMG has been promoting safeguards to prevent unwanted developments (“a slippery slope”) and focused on three items. Besides mandatory reporting the second step is the condition of an independent collegial consultation before a physician ends life. This condition has become institutionalized, by establishing regional chapters of specially trained physicians to perform that task, the so-called SCEN physicians: Support and Consultation on Euthanasia in the Netherlands. Its physicians, now more than 600, provide support for physicians with questions and carry out the legally required consultation prior to euthanasia. From 1997 the cooperation between the KNMG and the Dutch legal authorities resulted in a third step: an evaluation procedure after the act on a case-by-case basis of each case reported. After reporting every case is to be reviewed by one of five Regional Euthanasia Evaluation Committees, each consisting of a lawyer, a physician, and an ethicist.

Politics

Not only was there a division within the medical profession on the subject of acceptable euthanasia, there also was a divide between the Dutch political parties. Liberals supported a lenient approach and legalization; Christian Democrats, for decades one of the largest factions in Parliament, opposed it; while the Socialist parties were divided. The government inaugurated a State Committee on Euthanasia in 1982; its report being published in 1985 came out in favor of regulating acceptable euthanasia, but a minority report also reflected divisions. The coalition government, including Christian parties, decided to depoliticize the issue in 1990 by inaugurating a committee with the task to produce an inventory of all medical decisions at the end of life, the so-called MDELs. The outcome was both reassuring and disquieting – reassuring because the absolute and relative figures of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide were relatively low, 1.7 % and 0.2 %, respectively, of all deaths.

In the years 2000 and on, the Netherlands passed a “euthanasia law” in 2002, officially termed: The Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act. It describes the so-called criteria of due care after which both assistance in suicide and the active ending of life shall not be prosecuted. A physician must:

(a) Be satisfied that the patient has made a voluntary and carefully considered request

(b) Be satisfied that the patient’s suffering was unbearable and that there was no prospect for improvement

(c) Have informed the patient about his situation and his prospects

(d) Have come to the conclusion, together with the patient, that there is no reasonable alternative in the light of the patient’s situation

(e) Have consulted at least one other independent physician, who must have seen the patient and given a written opinion on the due care criteria referred to in (a) to (d) above

(f) Have terminated the patient’s life or provided assistance with suicide with due medical care and attention

(Active Voluntary) Euthanasia In Numbers In The Netherlands

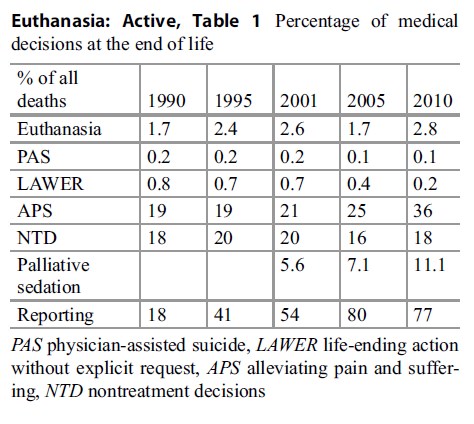

Since the research of the 1990 Committee to Investigate the Medical Practice Concerning Euthanasia representative figures on a national scale of all medical decisions at the end of life are available. Research has been repeated every 5 years since. The outcome is shown in Table 1.

Two items need more attention: (voluntary active) euthanasia and LAWER, life-ending action without explicit request, generally considered as nonvoluntary euthanasia.

(Voluntary Active) Euthanasia

The numbers of (voluntary active) euthanasia proved to be lower than expected without a significant increase over 20 years. Since the establishment of the RTEs in 1998, the reported numbers to the committees also have remained fairly stable, but from 2010 onward however the ERC’s yearly reports show a substantial increase in the absolute numbers of PAD, not reflected in the national investigations before and including the 2010 figures.

Table 1. Percentage of medical decisions at the end of life

Table 1. Percentage of medical decisions at the end of life

What has become clear also is an expansion of medical diseases and qualities that have become acceptable under the euthanasia law. The numbers show an increase in ending the lives of Alzheimer’s patients. For chronic psychiatric patients there is also a growth that is reflected in the numbers. However, the general conclusion is that there is no sign of “a slippery slope,” since the developments with respect to patients’ characteristics are all considered legal and within the boundaries of the euthanasia law (Tweede Evaluatie Wet Toetsing Levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding 2012). This law satisfies the goals of societal control of life ending after a request and increases transparency and legal security for physicians.

LAWER: Nonvoluntary Euthanasia Or Life-Ending Action Without Explicit Request

In the national research from 1990, the appearance of this LAWER group of MDELs was a surprising finding that caused national and international upheaval since it suggested a practice, at the time of 1000 cases, of the ending of life of patients without a request. The case descriptions suggest an intended end to life through applying medication primarily used to alleviate suffering, but with an expected speeding up of death to come. Since 1991 the absolute numbers have been sharply reduced.

The findings show that most of these cases concern extremely ill patients with a life expectancy of hours to days. While in most cases communication no longer was possible because patients lost consciousness due to their diseases, there were also cases where communication was possible but did not occur. One explanation was a dominant characteristic of a then still “normal” situation in 1990 that some patients (and families alike) would expect doctors “to do what is best” (Pijnenborg et al. 1993, pp. 1196–1199).

Belgium

Belgium is the second country where active voluntary euthanasia was made possible by a law in September 2002, just half a year after the Dutch euthanasia law came into effect. Developments in this country were quite influenced by events in the neighboring Netherlands, where since 1997 a “notification procedure” for euthanasia and assisted suicide was agreed on between the state, prosecuting authorities, and medical profession.

In Belgium the public debate about euthanasia slowly appeared in the 1970s but gained substantial momentum in political discussions in the mid-1990s. An essential difference between Belgium and the Netherlands with respect to voluntary active euthanasia is the simultaneous timing of the issues of euthanasia, palliative care, and patients’ rights: euthanasia is embedded in palliative care (VandenBerghe et al. 2013, pp. 266–272).

Politics, The Medical Profession, And The Courts

As in the Netherlands politics were divided on euthanasia, with Christian Democrats, longtime participants in coalition governments, opposing and liberals and socialists more or less supporting changing the Penal Code on this chapter. Belgium is far less secularized than the Netherlands, and the voice of the churches, especially the Roman Catholic Church, played an important role in the public debate. Euthanasia bills were submitted to parliamentary vote in 1995, but none resulted in a change of law, and “finding common ground” was delegated to a Consultative Committee on Bioethics, with 35 representative professional members. They wrote two advices on euthanasia, on competent patients (1997) and on incompetent patients, including the topic of advance directives (1999). In the 1990s and before, the palliative care movement in general opposed euthanasia and did not participate much in the public debate, as if there were two realities. That situation came to an end with the specific Belgian concept of integral end-of-life care, in which euthanasia may be realized but necessarily has to be a final intervention after all palliative care options have been exhausted or considered.

Medical Profession And Courts

The medical profession in Belgium is organized into a law-based body called the Orde der Geneesheren, the Order of the Physicians, regulating the medical profession, especially administratively. In the euthanasia debates, the order has been notably absent, preferred no public discussion on the subject, and was unwilling to play a constructive role in the legislative process. Contrary to the Netherlands prosecutors nor courts played a role in formulating legal norms or conditions for euthanasia.

The Law

The Belgian law decriminalizes (voluntary active) euthanasia only for physicians when specific conditions are fulfilled. The legal conditions are: a request, voluntary, persistent, and repeated and also in writing, must come from an adult competent patient, being fully informed, in a medically speaking hopeless situation, with unbearable suffering for the patient due to accident or disease, with which the physician has to identify to the extent that euthanasia will be granted. An independent collegial consultation on the legal conditions must take place. Physicians must self-report their cases on official documents to a central committee.

Safeguards

The safeguards in Belgium are similar to the Netherlands: mandatory reporting, an independent collegial consultation before and review after the intervention. In Belgium a group of trained consultants has been established, comparable to the SCEN organization in the Netherlands, known by its acronym LEIF, Life End Information Forum, available for consultation and support in helping requesting physicians on any aspect of a euthanasia route. Review after actively ending life is by law delegated to the already mentioned Federal Control and Evaluation Committee.

Numbers in Belgium on active euthanasia, both voluntary and non-voluntary

The data on euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide (Table 2) divided in total numbers, in Flanders (Flemish) and in Wallonia (French speaking)

Table 2. Absolute numbers of euthanasia cases in Belgium

As in the Netherlands repeated evaluative research, with multiple and detailed projects on medical decisions at the end of life, has been made in both 1998 and 2001, including in 2011 an investigation on the effects of the euthanasia law on the practice (MELC Project 2011).

LAWER In Belgium: Nonvoluntary Euthanasia Or Life-Ending Action Without Explicit Request

The appearance of the so-called LAWER group of patients in the Dutch statistics after 1990 caused much turmoil in the ethical debates on acceptable euthanasia. Research in other European countries, such as Belgium, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland, showed unexpected results (Van der Heide et al. 2003). The percentages of LAWER in Belgium were 2.5 times the figures in the Netherlands. In an analysis in depth, Chambaere et al. came to the following conclusions. “In most cases physicians reporting life ending acts without explicit request did not label their acts in terms of life-ending, but rather in terms of symptom treatment.” The contradiction between intention and act may be explained by false ideas about the hastening of death of opioids. Nevertheless, a perception of these acts as a nonvoluntary ending of life still causes ethical questions, even though the analysis softens a view of an entirely nonvoluntary practice.

Luxembourg

Surprisingly, Luxembourg has become the third country allowing voluntary active euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Surprisingly, because the medical profession resisted this change strongly, a coalition government, not including Christian Democrats, formed after 2004, introduced a law decriminalizing euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide.

For some years there has been a major confrontation between pro-legalization and opponents of legalization. The final conclusion and passage of the “euthanasia law” on March 16, 2009 is by a majority vote of just one.

The Law

The Luxembourgian law has a structure similar to the Dutch and Belgian laws, with some differences. The similarities are that patients must request an end to life, being competent adults, with unbearable suffering, physically and mentally, from an incurable disease. Options for euthanasia must have been discussed in depth: thus after complete information of the patients, requests must be repeatedly, a discussion with the team of caretakers is a condition including a discussion with an appointed representative concerning the patients’ choices at the-end-of-life and may include also others involved in the process of care-taking.

The difference is the procedure of formal registrations of advance directives in case of incompetence with a national committee, to be checked every 5 years on its present status.

Reports must be made to the National Review Committee, consisting of nine members, of which three must be physicians, three lawyers, one representative of a Health Council, and two members of patient’s rights organizations.

A particular focus has been to assure that the practice is careful without the risk of causing additional grief to the fact that a person has requested help in dying.

Numbers

There are two reports on the extent of PAD in Luxembourg, required by law every 2 years. Over 2009/2010 the committee reported reviews on five cases.

It concerned persons over 60 years old, 3 women, 2 men, 3 in hospitals, and 3 at home. At the same time 681 persons had signed in with an advance directive. Over 2011/2012 the commission reviewed 14 cases. In 78 % it concerned patients with cancer and in 22 % chronic neurodegenerative diseases, with 1 person over 50 years old, 9 persons between 60 and 79 years, and 4 persons over 80 years. In these years since 2009, 1249 persons registered with an advance directive.

Conclusion

It is clear that the concept of “euthanasia, active” historically has a long and ambivalent content to say the least; the idea of a practice in the past and nowadays still is controversial for many. There have always been proponents, especially outside of the medical profession in the general public, and a minority of physicians have played and still play a major role in trying to realize legality for this intervention. However, opponents to legalization in most countries maintain a status quo of resistance, not in the last place in the medical professional bodies. In the past there have been inclinations and a reality in Germany before and during the Second World War, to extend ending life to others than requesting extremely suffering patients, such as physically and mentally handicapped persons. But these limits seem to be honored where euthanasia is practiced nowadays. Where there are openings for assisted-dying, the option of assisted suicide is preferred, but when both practices are legal, the overriding choice is for euthanasia. However, only physicians are allowed to perform the intervention to end a life.

The subject of euthanasia remains high on the agenda in many countries but has only been realized in laws in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. In several states in the USA and the Canadian province of Quebec, physician assisted dying is a legal option. Where there is research, it shows that the rules, regulations, and safeguards are in place in order to guarantee a careful practice, before and after euthanasia, without signs of a slippery slope.

Bibliography :

- Chambaere, K., Bernheim, J. L., Downar, J., & Deliens, L. (2014). Characteristics of Belgian ‘life-ending acts without explicit request’: A large-scale death certificate survey revisited. CMJA Oen. doi:10.9778/ cmajo.20140034.

- Finns, J. J., & Bachetta, M. D. (1995). Framing the physician-assisted suicide and voluntary active euthanasia debate: The role of deontology, consequentialism and clinical pragmatism. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 43, 563–568.

- Gesundheit, B., Steinberg, A., Glick, S., Or, R., & Jotkovic, A. (2006). Euthanasia: An overview and the Jewish perspective. Cancer Investigations, 24(6), 623ff.

- MELC Project. (2011). Monitoring the end-of-life care in Flanders. In Palliatieve Zorg en Euthanasie in België [Palliative Care and Euthanasia in Belgium]. Brussel: Uitgeverij ASP.

- Pijnenborg, L., Van der Maas, P. J., Van Delden, J. J. M., & Looman, C. W. N. (1993). Life-terminating acts without explicit request of patient. Lancet, 341, 1196–1199.

- Rachels, J. (1975). Active and passive euthanasia. New England Journal of Medicine, 292, 78–80.

- Staatscommissie Euthanasie. (1985). Rapport van de Staatscommissie Euthanasie [Report of the State Committee on Euthanasia]. ‘s-Gravenhage: Staatsuitgeverij. Tweede Evaluatie Wet Toetsing Levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding [Second Evaluation of the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act]. (2012). Den Haag: ZonMW.

- VandenBerghe, P., Mullie, A., Desmet, M., & Huysman, G. (2013). Assisted dying – The current situation in Flanders: Euthanasia embedded in palliative care. European Journal of Palliative Care, 20(6), 266–272.

- Van der Heide, A., Faisst K., Norup, M., Paci, E., Van der Wal, G., & Van der Maas, P. (2003). End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: A descriptive study. Lancet. http://image.thelancet. com/extra/03art3298web.pdf

- Youngner, S. J., & Kimsma, G. K. (2012). Physicianassisted death in perspective. Assessing the Dutch experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.