This sample Advocacy Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Advocacy is acting for others. Health professions have a long history of acting for others and an equally long history of ethical debate and discernment about such action and its scope and limits. This entry will outline historical trends in how health professionals have understood the balance of their responsibilities between the individual patient and the broader community. There is also discussion of definitions and conceptions of advocacy and how advocacy has been incorporated into various ethical codes and charters of the different health professions. Lastly, there is a discussion of ethical tensions and conflicts that arise in performing advocacy and the changes in the modern era that have heightened calls for advocacy as a core professional responsibility.

Introduction

Advocacy is taking action on behalf of another individual. While acting for others is simple in conception, advocacy is far more complex in application. Much of the rest of this encyclopedia is concerned with discerning right action. This discussion starts with the assertion that advocacy is the method of right action that follows a process of ethical discernment. In witnessing an individual suffering harm or injustice, the expression of right action, the appropriate ethical behavior, is to advocate for the remediation of the unjust situation or for the removal of the source of harm. Many professions are concerned in some way with advocacy. Lawyers advocate for their clients. Clergy advocate for their parishioners. Physicians and other health professionals advocate for their patients. In accepting payment, a fiduciary responsibility to another, a professional commits to act in the best interest of another. And yet, not all professionals under the same circumstances will discern the same right action or act in the same manner. Uncertainty is thus one of the principal challenges of advocacy. Making a decision is one thing. Acting on that decision is another thing entirely. Action ventures from the hypothetical to the concrete. Action commits history to a new course. A decision carries no consequences; an action ushers in an outcome. In acting, an individual may serve another, but risks all the consequences that come from that action. Acting – advocating – entails risks. Health professionals act daily in the face of uncertainty, yet advocacy may entail a call to action where they have no experience to even define the elements of their uncertainty.

Advocacy in the context of health unearths a number of tensions and challenges to be explored in this entry. Risks of advocacy include that vicarious action risks paternalism. Justice pits the interests and concerns of the many against the needs of an individual and vice versa. In the midst of this is the healthcare professional, steeped in science and trained for technical mastery but rarely prepared to venture beyond the sphere of clinical practice, even when the path to health for their patient and their patient’s community may lead them there.

The boundaries that define these tensions have shifted greatly over the centuries and will continue to do so long into the future.

Historical Context Of Advocacy

Advocacy And The Healthcare Professions

Health professions have defined their obligations most clearly in the context of a dyadic relationship between provider and patient. Within that dyad, right action is most easily understood in the interest of a single individual. The duty to the individual is the bedrock of the moral authority of healthcare professions, and much of the historical ethical exegesis is concerned with the nature of this relationship and how best to honor it and its obligations. Yet a professional’s obligation to the individual quickly finds its limits as the understanding of illness has progressed from a threat to a community, to the threat to the individual, and back again.

One of the earliest documents of the ethical requirement of professionals committing to healthcare is the Hippocratic Oath. In use to this day for physicians graduating from school in many, particularly Western, countries, the physician promises to serve the individual to the best of their knowledge and to preserve the individual’s privacy. Many subsequent philosophers of medicine, across multiple religious traditions, upheld the importance of this commitment, from Galen to Maimonides and Avicenna. Galen begins to raise the tension of the duty to the patient and duty to a wider community as he writes of his experience in caring for the gladiators of Rome and weighing the demands of the priests and generals against the individual (Hafemeister and Gulbrandsen 2009).

In Medieval Europe, in response to the threat of the bubonic plague, the object of the physician’s advocacy began to transfer to the community, as a means of serving the individual. As Geraghty and Wynia (2000) have discussed, a system of physicians linked to communities arose in Europe in the fourteenth century, in response to the public health challenges brought by successive waves of the plague. The understanding of communicable disease led physicians and communities to develop systems of quarantine to try to isolate sick individuals and protect larger communities. Communities hired physicians and contracted for health services for the local population in return for money and property. The physician had a role to act or advocate for the health of both individuals and the community they lived within.

Following the Renaissance, and the plague, were waves of famine and other illnesses. A shift of perception arose, and illness came to be associated with poverty. Physicians were called on to serve the community by treating both physical illness and social problems, which were often seen as linked, and patients were often treated based on beliefs about whether the patient was “worthy” within the community. Criteria for worthiness included belonging to the community, being employed, or being old. The determination of worthiness was a form of stewardship of community resources, and it was part of the relationship between the physician and patient. Those not deemed worthy were excluded from the possibility of medical treatment in that community. Often the ill and poor were institutionalized. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, physicians came to reincorporate service to those disenfranchised. Serving the institutionalized became a means of healing both health and social problems that were often seen as equivalent at this time (Geraghty and Wynia 2000).

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as epidemics abated and industrialization grew, the delivery of medical treatment became more regulated and centralized by governments in Austria, Germany, and France. In contrast, a fee-for-service free-market system prevailed in the USA and the UK. Both consumers and physicians recognized a potential conflict of interest in this type of fee-for-service market. Licensure and regulation were also less centralized, and consumers were distrustful of the capacity of the physicians they engaged. Physicians recognized that the direct remuneration from individuals could challenge their broader obligations to the community and to public health. This led to the development of a professional Code of Ethics (Thomas Percival’s Medical Ethics, 1803, and the Code of Medical Ethics of the American Medical Association, 1847) that sought to provide guidelines to physician behavior with respect to the potential for individual payment to undermine the correct medical treatment and the physician’s responsibility to the health of the community. In the USA, most physicians practiced in small communities, and their relationship to those communities and self-interest in preserving a patient base led to some internal control on how much their attention could be deflected away by pure financial gain and a singular focus on the individual.

The explosive development of biotechnology since the 1960s led to an acute refocusing of the physician’s attention to the individual, and the immersion into the microhabitat of the patient’s body, and the function of disease. The proliferation of effective treatments that achieve their effect within that microhabitat powerfully focused the provider’s attention inward toward the patient and away from the external habitat – the community and environment in which the patient lived. This “atomization” of medicine driven by medicine’s increasing diagnostic power and the efficacy of new treatments, and closely aligned with the economic imperatives of profit, has the side effect of divorcing the disease from the patient and left the patient’s context and environment unseen and untouched by most healthcare professionals.

Yet in the current environment of big data, modern science has simultaneously revealed the micro-frontier of “personalized medicine” and illustrated with dramatic certainty that the context of community and environment has a far greater impact on the expression of health for the patient than the vast array of personalized treatments proliferating in the realms of pharmaceutical and procedural therapies.

At the start of the twenty-first century, healthcare providers again are faced with new crises in which to reconsider their roles. From novel epidemics to global climate change and to the exponential and unsustainable growth in the cost of medical therapies, providers are currently asking themselves about the boundaries of the provider-patient relationship and the duty a health professional has to the broader community. In the face of these pressures, healthcare professionals are being called on to speak as technical advocates. Particularly with the increase in complexity of both medical treatment and treatment delivery systems, the provider’s voice is invaluable in informing consumers, communities, and governments about the need for changes and the potential outcomes of proposed policies and regulations. Given the modern global dynamics of health, advocacy in this context moves beyond the local distribution of community resources or addressing social justice, to action for security, health, and wellness of a global community.

Advocacy And Professional Codes Of Ethics

In caring for a patient, a provider might define her duty as an advocate by providing care and working to ensure access to the treatments and resources that an individual requires to treat illness and disease. However, such a perspective takes a very narrow view of her duty to prevention. Over the past half century, science has produced overwhelming evidence that the places that people work, live, and play have a significant impact on an individual’s health and that in fact, the context in which people live out their lives has a far greater impact on health than healthcare itself. In the face of such facts, the provision of care alone is an inadequate response if prevention of harm remains an ethical obligation.

Some health professional organizations have acknowledged this changing ethical landscape by broadening the scope of professional purview to include a call for advocacy. The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), for example, in its charter on medical professionalism (ABIM Foundation 2002, p. 245), called for a “commitment to the promotion of public health and preventive medicine, as well as public advocacy on the part of each physician.” The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (CanMEDS 2015, p. 5) includes “advocate” as one of the seven core functions of a physician or surgeon. The American Medical Association (AMA) endorsed a still broader commitment, stating that physicians must “advocate for the social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being” (AMA, Declaration of Professional Responsibility, 2000, Item 8). The National Association of Social Workers’ Ethical Standard 6.04 endorses that “Social workers should engage in social and political action that seeks to ensure that all people have equal access to the resources, employment, services, and opportunities they require.. ..and should advocate for changes in policy and legislation to improve social conditions.. ..to promote social justice” (NASW Code of Ethics 2008, p. 23). In each of these cases, the responsibility is clearly labeled as one shared by every individual. In other cases, the responsibility is defined collectively, for the profession as a whole. For example, the American Nurse Association, in their Code of Ethics, states “It is the responsibility of a professional nursing association to speak for nurses collectively in shaping and reshaping health care within our nation, specifically in areas of health care policy and legislation that affect accessibility, quality, and the cost of health care.. .. In these activities, health is understood as.. .extending to health-related sociocultural issues such as violation of human rights, homelessness, hunger, violence, and the stigma of illness” (ANA, Code of Ethics, 2015, p. 31). Other health professional organizations including the American Association of Physician Assistants and the American Association of Medical Assistants also encourage members to participate activities aimed toward improving the health and wellbeing of the community.

Ethical Dimensions Of Advocacy

Defining Advocacy

“Advocacy is action by a .. .[healthcare provider]… to promote those social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate the suffering and threats to human health and well-being that he or she identifies through his or her professional work and expertise” (Federico et al. 2010, p. 63). This definition addresses the intention of health advocacy to improve health and well-being and reduce suffering, but intentionally leaves out clinical activity as a form of advocacy. In accordance with the previously discussed professional oaths and ethical practice statements, clinical action is an expected expression of routine ethical practice. Healthcare advocacy assumes action beyond the clinical realm, to improve health and well-being through action for ethical principles in the wider context of the individual patient and the community they live within.

Advocacy And Distributive Justice

For most of the recorded history of medicine, the most common dilemma of justice was one of distributive justice. How does an ethical professional earn a living and still provide care for those in need? Hippocrates asserted that physicians should “Sometimes give your services for nothing.. . If there be an opportunity of serving a stranger in financial straits, give him full assistance” (Daikos 2007, p 620). Henri de Mondeville, a surgeon in the Middle Ages, perhaps summed the solution up most succinctly: “.. .you must treat the poor free for the love of God, you must make the rich pay dearly” (Power 1968, p. 20). In other words, advocating for justice was the task of an individual and was meted out in face-to-face interaction. Justice came in saying “yes” to the poor while demanding more from the wealthy. Individual providers, most often physicians, provided care for those in need and balanced their work for individuals against their need to earn a living.

The evolution of healthcare over the last century has altered this landscape and with it the challenge of advocacy for justice in the modern era. Consider medicine as an example. For most of its history, medicine behaved as a professional guild. The guild established criteria for entry, established standards of performance and conduct, and trained the next generation. The state of the art evolved through the ingenuity and effort of individual members of the guild who shared the fruits of their creativity and discovery within the guild. While elements of the guild remain in health provider professional organizations, the ingenuity and effort of individuals have been privatized to for-profit medical device and pharmaceutical manufacturers worldwide and for-profit insurance companies, hospitals, and physician groups in select markets. The subsequent cost to individuals and communities has the potential to destabilize entire economies. The USA is the most well-known of these challenged systems, where one in five citizens has personal debt for healthcare and businesses’ stability is undermined in global competitiveness by healthcare costs for employees that have increased >10 % each year, for several consecutive years. The juggernaut of healthcare industry, while benefiting many people with more effective medical treatments, is undermining other engines of health within society, through its terrific cost. Access to healthcare is in many economies (China, India, the USA) limited only to those who can afford it.

In response, healthcare is increasingly seen as a public good. Health of citizens is an asset that benefits all of society, in the form of more able workers, more participative students, and more revenue to the state, and decreased state and private expenditures for illness. Additionally, the public finances medical progress through research while heavily subsidizing the education and training of health professionals. In most developed countries, the public funds the majority of medical services. Even in the USA, where private financing has been jealously preserved, the government funds a majority of all medical care.

In the past, a single provider or a small group of providers might constitute the entire healthcare system for a community. That individual or group was the sole means of addressing inequities in the distribution of healthcare resources. Under those circumstances, offering free care to the poor was an act of justice. Today, in most instances, providers can care for their patients with the expectation of being paid. Providing care for free is no longer an act of justice, it is an act of charity. This is a critical distinction to make. Charity is a gift given at the caprice of the giver. Justice is a structural response that, if perfectly applied, would eliminate the need for charity. In the modern era, an ethical obligation to justice can only be accomplished through advocacy.

Justice And The Social Determinants Of Health

As previously noted, despite the tremendous advances in biomedical sciences over that last century, the provision of healthcare is a small contributor to overall health.

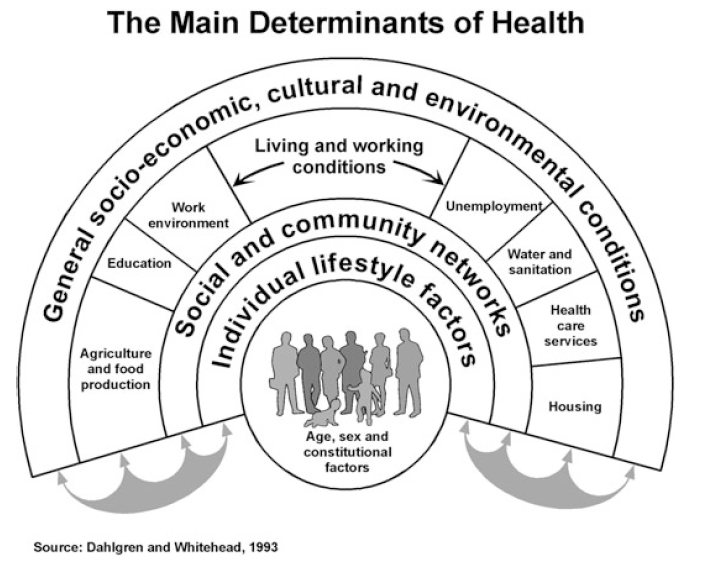

Figure 1. The main determinants of health

Figure 1. The main determinants of health

In fact, data suggest that only 10–15 % of a person’s health status can be attributed to healthcare; the remainder of an individual’s health, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (Dahlgren and Whitehead 1993), is determined by genetics, behavior, the environment, and a host of other sociocultural factors that have been termed “social determinants of health.” Again, note that if the obligation of the health profession is the improvement of health and well-being of individuals, then limiting a provider’s actions to the clinical care of an individual is an inadequate response to achieve health. Acting on the broader determinants becomes the purview of health professionals who are called through ethical discernment, and the pursuit of health, to take additional steps to address these determinants of health through advocacy.

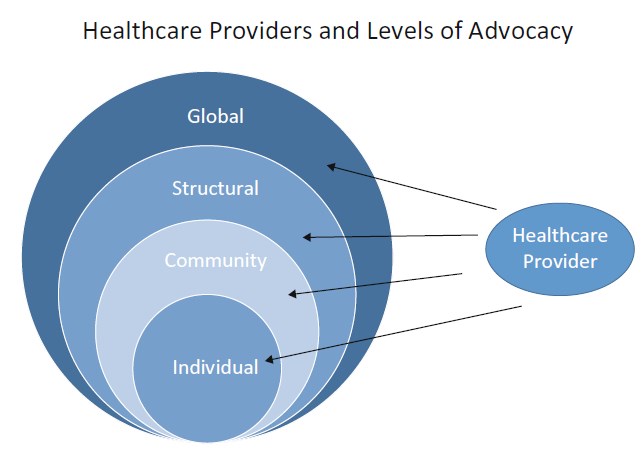

For a health professional, action within the sphere of clinical work is most clear and easily understood. Action beyond that sphere is more difficult to envision and achieve. To consider the scope and target of those actions, this model, built on the work of the Center for Strengthening Youth Prevention Paradigms in Los Angeles (see Fig. 2), is offered as a tool to narrow and define a course of advocacy. This figure describes levels of advocacy as a gradient that begins with the individual and reaches outward, first into the community and then beyond to the realm of institutions and policy. Within each level, one can visualize the targets of advocacy and consider a set of actions that may result in improvement in health or the opportunity for health.

Individual Advocacy

Individual or patient level advocacy encompasses both the actions of a provider with a patient and the provider’s exploration of other influences on the behavior and choices of the patient. A provider’s capacity to help an individual achieve health may involve an exploration of the patient’s beliefs and ways of changing health behaviors. This exploration may rightly include education, assessment of readiness for change, and assistance in anticipating and planning to overcome barriers. Individual patient advocacy may involve a small step beyond a purely clinical response to fill out a form for a patient, or look for community-based resources for the patient, or refer the patient to other supportive resources in health, mental health, or social support. While advocacy at the individual level is most grounded in the immediate circumstances and desires of the patient, even at this level, tensions with autonomy exist. For example, the individual may have no desire to relinquish a harmful behavior, like smoking, and yet the provider is compelled to lead the individual toward changing that behavior and not to simply yield to the patient’s most immediate desires.

Figure 2. Levels of advocacy for healthcare providers on behalf of patients

Figure 2. Levels of advocacy for healthcare providers on behalf of patients

The ethical dimensions of individual level advocacy start with the most traditional expression of beneficence and non-maleficence. The providers’ exploration of the individual’s experience theoretically enhances their efficacy in assisting that individual to change their behavior or circumstances to improve their prospects for health. Such an approach moves away from the traditionally paternalistic care delivery model, where the provider delivers “the best of their ability,” and focuses instead in a newer patient centered model. Non-maleficence in individual advocacy involves choosing treatments wisely and guiding patient choices. Addressing issues of justice may seem more difficult within the individual level. Consider, though, that illness may arise directly from unjust circumstances. For example, substandard housing may cause and sustain a case of refractory asthma in a child, while the landlord offers no redress. In such cases, justice compels a provider to advocate beyond the clinical arena, turning their attention to resources within the community, like housing authorities or legal assistance.

Community Advocacy

Beyond the individual lies the community. In advocating at the level of the community, the provider acts not from the standpoint of the patient facing out, but rather seeks to affect the context within the community that in turn impacts the patient. Such actions, committed on a patient’s behalf or compelled by their example or experience, may include gathering data, reporting inequities, providing education and guidance to community organizations, or helping to convene or support stakeholders to address an issue impacting health.

As a provider gains an understanding of the patient’s environment, he may be challenged by the complexity of their world and his efficacy in affecting it. The levers of change in the community may be less clear, and actions to move those levers may seem beyond his control, ability, or purview. Witnessed injustices through inadequate housing, food deserts, access to clean water, or exposure to environmental toxins confront him with social injustice in a very broad context. Yet the provider may be the only member of the community capable of connecting the harm accrued to the patient to structural injustice in the community. When Rudolf Virchow declared “The physician is the natural attorney of the poor,” it was this reality he recognized. Many providers have been integral to identifying harm in the community and environment through keen observation and systematic research. From John Snow who famously removed the Broad Street pump handle and ended the London cholera epidemic to countless unsung practicing providers who pen an editorial, speak before a school board, or call a reporter, there are countless examples of health professionals sounding an alarm and initiating a response to a source of harm they have identified. Notably, each of these examples represents a step beyond the patient – a challenge common to addressing threats to justice and advocacy at the community level.

Most often a provider can attend to beneficence, non-maleficence, and the preservation of autonomy, with her attention singularly focused on the patient and never straying beyond that relationship. With justice, that is rarely, if ever, the case. To even consider justice, one must place the patient in relation to others, for it is through relationship and by comparison that justice is defined. Justice must be considered in the context of family, community, and society as a whole. What is fair for one cannot be discussed without considering what is fair for others, and advocacy in this context involves a set of actions with a broader reach.

If the action is vicarious, as it may be at the level of community, advocacy may bring challenges in terms of beneficence, non-maleficence, and autonomy as well. A provider may act on behalf of a patient and set off a chain of events that result in an outcome that is not desired by the individual who inspired the action in the first place. An individual victimized by domestic violence or an elder who is unsafe in their home may not desire any action by the provider to change their circumstances and may view conditions that would remove the immediate source of harm as a form of harm itself. While ideally an act of advocacy would align completely with a patient’s perception of their own benefit, advocacy that extends beyond the patient into the community may entail tensions between competing perceptions of benefit and harm that an advocate must confront.

Structural Advocacy

Addressing some sources of harm or injustice may require action beyond the relational and sociocultural resources of the community to address the structural sources of harm. In these cases, advocacy involves engagement with the individuals and institutions that set policy and allocate resources. The scope of this work could be local, regional, or even national. In engaging in structural advocacy, a provider acts not as a clinician, but as a citizen in the public square. In this capacity, a physician or nurse or other health professional is not just any citizen, but a citizen with a particular privilege and responsibility conferred by the nature of their specialized knowledge and experience and their fiduciary duty to their patients. As noted before, the health professional is uniquely able to identify the sources of harm their patients and communities encounter and to evaluate and recommend responses to attenuate the risk. Gruen, Pearson, and Brennan (2004) use the term “physician-citizen” to describe the role of doctors acting publicly and visibly in furthering the public’s health. They posit that this form of professional leadership has declined in the last half century; as physicians turned their attention to the remarkable expansion in biotechnology, they increasingly neglected their centuries-old tradition of advocating for the health of the community.

Structural advocacy can encompass many activities and, in democratic societies, begins with the simple act of voting – the most basic duty of citizenship in a modern society. The ethical obligations of a health professional certainly require that their values be expressed through value-driven participation at the ballot box. Structural advocacy might further entail contributing to collective action through coalitions, professional organizations, or organized political activity, or it might entail individual actions such as lobbying policy-makers; providing technical information and analysis in the form of education, position papers, or testimony; or providing leadership to organize and develop others for collective action. Structural advocacy can be very local – such as action to change the policies of a health system or local school board or it could entail action intended to change the laws or policies of a nation. As noted above, health professionals are uniquely positioned to contribute to structural advocacy by nature of their expertise, but also through the trust they are afforded by the public. Indeed, the professional voice is a unique and essential ingredient in structural advocacy, and its absence can result in the propagation and prolongation of harm and injustice.

Structural advocacy presents several ethical challenges. For example, the advocate, through their actions to address the needs an individual, risks creating a response that the patient might oppose. For example, over the last few decades, many health professionals in the USA have advocated forcefully and effectively for an expansion of health insurance coverage to address the inequities faced by their patients. The ultimate result of that action – the Affordable Care Act – is a policy that a large number of their patients may oppose. In this case, their actions may have been beneficent, achieving their intended result of providing access and security, while the patient perceives some harm from an economic, social, political, or ideological perspective.

In considering the risks to autonomy from advocacy, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (a US-based health philanthropy) notes a core challenge to acting for others in the name of health: to put it plainly, others may not want the help. The Foundation recommends operating through a guiding principle that “all should have the opportunity to make the same personal choices to improve their health” (Lavizzo-Mourey 2014, p. 11). In theory, if one is successful in advancing this principle in advocacy work, any negative impact on autonomy created by a structural change would be offset by an increase in the potential for personal autonomy created by the change itself.

In the structural advocacy, an immediate impact on the individual is far less likely, and thus adverse outcome relative to beneficence and non-maleficence is of less pressing concern. In structural advocacy, the harm avoided or the benefit imparted may accrue broadly, over time, to a large number of individuals and yet may not ever accrue to the individual or individuals who inspired the health professional to act in the first place. Since the interests of the professions are ostensibly aligned with the interests of the communities and individuals they serve and since the impacts of structural advocacy are so broad, conflicts of interest are of particular concern. For example, a common critique is that providers are far more likely to be active in the public square when their reimbursement is at stake. While there is clearly a relationship between the livelihood of health professionals and secure access to care, there is a clear conflict of interest in this area of advocacy, and the needs of patients and the public may easily become secondary to the financial interests of providers. Health professions undermine the public trust and the efficacy of their own advocacy if they are only engaged when their own interests are at stake. The power of the provider’s voice in the public square is their commitment to the interests of others and their pledge to put those interests first, above their own. This altruistic commitment, combined with the dispassion of science, can temper and humanize debate and moderate political rhetoric. It is the ability to speak authentically and truthfully for the interests of others with deep wisdom and knowledge that makes the health professions’ voices so essential in structural advocacy. In this manner, the health professions are uniquely positioned to balance the power and interests of commerce and the state for common good.

Global Advocacy

In the modern era, health has become increasingly global. Epidemics are blind to borders, social disorder tends to metastasize, and policies that work well for one population may have disastrous consequences in another. In many ways, the three levels of advocacy described above can be applied globally. An individual may act for the interests of another individual with whom they share no ties of culture, language, or geography. A health professional may advocate within the global community through relationships and networks to improve the health of others locally or far afield. Finally health professionals can advocate for structural change, recognizing that this work can be far more complex than accomplishing structural change at home. Examples of such work are numerous. The founder of the Red Cross, Henri Dunant, received the Nobel Prize for founding a humanitarian organization dedicated to alleviating the suffering of individuals and communities and to protecting the human rights of war combatants. Albert Schweitzer, who received the Nobel Prize for his individual work and advocacy on behalf of the inhabitants of Gabon, used the prestige of the prize to advocate against nuclear weapons and raise awareness of the health consequences of ionizing radiation. Bernard Lown and Yevgeniy Chazov shared the prize with others, for their work in forming International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, a global organization that effectively worked worldwide to stop the proliferation of nuclear warheads as a potential cause of sudden planetary extinction. As these examples illustrate, health professionals have been particularly effective at advocacy for global health.

As the volume of data grows demonstrating the powerful linkages between noncommunicable diseases and social factors like poverty, inadequate access to food and safe water, and social disorder and stress, health professionals will be increasingly challenged to return to the public health focus they embraced in previous centuries. Similarly as the world grows ever more connected, health professionals will be increasingly challenged to think and act – to advocate – in a manner that respects the global nature of health and its determinants. The contemporary epidemics of Ebola, SARS, and MERS highlight that globally, social justice in the developing world is inseparable from health security in developed nations. In addition, these epidemics serve as a terrifying and constant reminder of the need for health providers to connect the concerns of the patients in front of them with broader, global efforts in social justice and public health.

Conclusion

Bridge the gap between rhetoric and reality. (Gruen, RL)

Advocacy is the expression of action for justice. As such, justice must be measured and not blind to the needs of the individual or community that the healthcare provider intends to act for. To achieve this, measures of beneficence and non-maleficence must be conscientiously applied to these actions and not just to our intent in performing the actions. Throughout the history of medicine and the health professions, there has been a tension between the needs of the individual and the needs of the community. Over the arc of that history, through changes in time and culture and in the face of wealth and famine, the balance has shifted, favoring at some times the individual and at other times the broader community. In operationalizing advocacy at levels from the individual to their community and the structural and global environment that impact that individual, a better framework for understanding the action that providers can take will hopefully be provided, as well as accountability for their action across the spectrum of the patient’s networks. In our awareness of the tension between these ethical constructs and the intersection of the needs of the individual and the needs of the community, the capacity to weigh these elements conscientiously serves to improve the aim and impact of health provider advocacy.

Bibliography :

- ABIM Foundation. (2002). Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136, 243–246.

- American Medical Association. (2000). Declaration of professional responsibility. Appendix. In Council on ethical and judicial affairs. Code of medical ethics –current opinions, 2000–2001 (14th ed., pp. 144–145). Chicago: American Medical Association.

- American Nurse Association. (2015). “Code of Ethics”. Retrieved from http://www.nursingworld.org/codeofethics. Accessed 7 Oct 2015.

- Center for Strengthening Youth Prevention Paradigms, Los Angeles, CA. (2012). HIV prevention at the structural level: Defining structural change. Retrieved from http://www.chla.org/atf/cf/%7B1cb444df-77c3-4d94-82fa-e366d7d6ce04%7D/SYPP_DEFINING_STRUC TURAL_CHANGE.PDF. Accessed 3 Jan 2015.

- Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (1993). Tackling inequalities in health: What can we learn from what has been tried? Working paper prepared for The King’s fund international seminar on tackling inequalities in health, September 1993.

- Ditchley Park, Oxfordshire. London: The King’s Fund. Accessible in: Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (2007). European strategies for tackling social inequities in health: Levelling up Part 2. Copenhagen: WHO Regional office for Europe: http:// www.euro.who.int/ data/assets/pdf_file/0018/103824/ E89384.pdf

- Daikos, G. (2007). History of medicine: Our Hippocratic heritage. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 29, 617–620.

- Federico, S., Wong, S., & Earnest, M. (2010). Physician advocacy: What is it and how do we do it? Academic Medicine, 85(1), 63–67. doi:10.1097/ ACM.0b013e3181c40d40.

- Frank, J. R. (Ed.). (2005). The CanMEDS 2005 physician competency framework. Better standards. Better physicians. Better care. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

- Geraghty, K., & Wynia, M. (2000). Advocacy and Community: The social roles of physicians in the last 1000 years. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/418847. Accessed 3 Jan 15.

- Gruen, R. L., Pearson, S. D., & Brennan, T. A. (2004). Physician-citizens – Public roles and professional obligations. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 94–98. doi:10.1001/jama.291.1.94.

- Hafemeister, T., & Gulbrandsen, R. (2009). The fiduciary obligation of physicians to “Just Say No” if an informed patient demands services that are not medically indicated. Seton Hall Law Review, 39, 335–385.

- Lavizzo-Mourey, R. (2014). Building a culture of health: 2014 President’s message. Retrieved from http://www. rwjf.org/en/library/annual-reports/presidents-message-2014.html

- National Association of Social Workers. (2008). Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Washington, DC: NASW.

- Power, D. (1968). Treatises of fistula in Ano haemorrhoids, and clysters by John Arderne. London: Oxford University Press.

- The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. (2015). CanMEDS: Physician competency framework. Retrieved from http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/ portal/rc/CanMEDS/framework. Accessed 7 Feb 2015.

- Dobson, S., Voyer, S., & Regehr, G. (2012). Perspective: Agency and activism: Rethinking health advocacy in the medical professions. Academic Medicine, 87(9), 1161–1164.

- Whitehead, M., Dahlgren, G., & Gilson, L. (2001). Developing the policy response to inequities in health: A global perspective. In Challenging inequities in health care: From ethics to action (pp. 309–322). New York: Oxford University Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.