This sample Animal Welfare Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Abstract

It has increasingly become important that Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees operate in research institutions across the globe to ensure proper care and use of animals for scientific research to be fully considered ethical. This was born out of the animal liberation debates of the 1970s which incidentally coincided with the bioethical impetus. In the Republic of Korea, the Animal Protection Act was introduced in 1991, but oversight of laboratory animal care and use in the research, testing, and education environment by an appointed ethical committee has been applied since 2008. Across the globe, Animal Care and Use Committees function under extant government and institutional policies and laws; and their responsibilities include training programs. Using the Korean experience, this research paper addresses the ethical issues related to animal welfare.

Introduction

There has been a radical transition in the use of animals as agricultural and food resources to “biological test tubes” for validating scientific hypotheses, evaluating therapeutic compounds, and learning pathologic processes. Whereas the benefits of biomedical research are often taken for granted, justifying animal experimentation on the basis of furthering human interests has increasingly come under attack. Thus, it is a fact that the external pressure of animal welfare is becoming greater to the developing countries recently. In the Republic of Korea, the terminal use of animals in biomedical research was routine by the mid-2000s; however, objections to the use of animals for this purpose began to arise, reflecting the overall change in social attitudes toward animals. These changes have been implemented into different legal and other forms of regulatory systems. Driven by both scientific needs and public concern about animal welfare and use, the Korean government implemented a national policy directed toward the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes. Since 2008, investigators planning to use animals for scientific purposes have had to complete an animal use protocol and submit it to an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (hereafter, IACUC) for approval, prior to commencement of the study. There are two Korean laws that govern the IACUCs of institutional animal research: the Animal Protection Act (hereafter, the APA) and the Laboratory Animal Act (hereafter, the LAA). According to a recent government annual report, 342 institutions had registered IACUCs with the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, and active committee members totalled 2,180 as of December 2013. In response to public concern via the animal welfare and protection advocacy group, there is a requirement that Korean IACUCs must include at least one-third of committee members who have “no conflict of interest in the relevant animal research institution.” The conduct of ethical evaluations by nonaffiliated (hereafter, unaffiliated) and/or nonscientific committee members for approval of the proposed animal protocol and the types of individuals chosen to fill these roles is key to successfully meeting the needs of local institutions (Mench et al. 1991). However, there is no guidance or training on how the unaffiliated member is supposed to perform their role (Haynes 2010) nor on the role of the nonscientific member on the committee regarding protocol review. This research paper has examined the current requirements for the IACUC composition and Korea practice on the role and requirements of the unaffiliated and nonscientific committee members. The authors primarily focus on (1) the normative issues involved in animal welfare, (2) the committee composition and qualifications for IACUC membership, (3) the term of the unaffiliated and nonscientific IACUC members, (4) the role and value of the unaffiliated and nonscientific members of the IACUC, and (5) guidance and training for unaffiliated and nonscientific members. Comparison of both legislations governing IACUCs is summarized from each of the authorized official websites, relevant literature, and published guidebooks, as well as drawing from diverse experiences in this field, and concludes with suggestions for quality improvements and for effective and efficient processes.

The Normative Issues Involved In Animal Welfare

A process that allows for evaluation of the ethical, scientific, and welfare issues is essential for animal uses in research, testing, and education. The process of ethical review involves evaluating an individual protocol justifying through h armbenefit assessment, ensuring application of the 3Rs – including good experimental design, animal housing, husbandry, and care – and confirming that involved staffs are adequately trained, qualified, and competent. All of these factors can have profound effects on both animal welfare and the quality of the scientific results obtained (Reed and Jennings 2008). Ethical review systems and process vary among different countries (Reed and Jennings 2008), institutions, and types of research field. There is a legislative framework to ensure application of the 3Rs’ principles and for the ethical review of protocols by the IACUC in the Republic of Korea; however, there are no standard guidelines and very limited training opportunities available on how to apply the 3Rs and where to find information on the subject. There are regulations governing the frequency of convened meeting; however, most of institutions registered to the government agency hold at least one IACUC meeting every 6 months to review animal care and use the policies set up by the institution. There is no institution in Korea conducting full reviews of protocols at a convened meeting, such as ethical review board of the human research subjects.

Based on the authors’ survey results on the attitudes of the Korean veterinary professors and students toward animal use and animal welfare issues conducted with the enactment of new APA in 2008, about 80 % of veterinary students favored animal use for their laboratory practices, believing that the use of animals is essential to meet learning objectives. About half of responding veterinary professors were uncertain as to whether alternative programs would achieve the appropriate learning objectives so as to replace live animal practice (paper in progress). Most current educators and decision makers were trained in unregulated circumstances, and they were in a favorable position to practice their skills using live animals. It is still very early to discuss whether scientific benefits override the use of sentient or “feeling” creatures; animals’ moral status geared toward minimizing and/or ending animal use in research at the international level. The discussion of normative issues involved in animal welfare deals with the ethical themes of animal sentience and moral status, and the question of animal rights should be shared after all personnel involved with the use of animals are adequately trained in the principles of ethical use and care of animals. In this regard, standardized guidelines, educational opportunities, and resource platforms are considered as high-priority things to do list at the government and institutional levels.

Committee Composition And Qualification Of The IACUC Membership

The IACUC is an institutional committee composed of practicing scientists experienced in research involving animals, specialists in veterinary medicine, animal care technicians, nonscientists, and lay representatives who oversee the care and use of animals used in biomedical research (Haynes 2010). According to Andrew Rowan, the original model for the IACUC was the Animal Ethics Review Committee established at the University of Southern California (Haynes 2010). The IACUCs are composed of people who are affiliated and unaffiliated with the particular research institution. The Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (PHS Policy) and the Animal Welfare Regulations in the USA mandate that one member of the IACUC be an individual who is not affiliated with the institution and is not a member of the immediate family of a person who is affiliated with the institution.

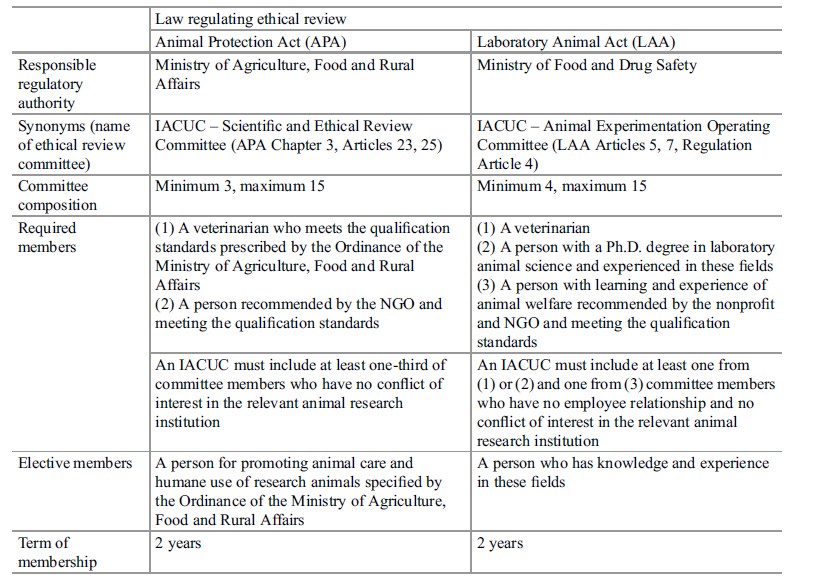

Korean IACUC structure was benchmarked from the US practice. The two Korean laws governing the care and use of research animals – APA and LAA – require that each institution conducting animal-based research, teaching, or testing establish an IACUC and certain members be included on the IACUC. IACUC membership must fulfill the following regulatory requirements: (1) a veterinarian, (2) a person recommended by the nonprofit and/or nongovernmental organization (hereafter, NGO), and (3) a person for promoting animal care and humane use of research animals, who all meet the qualification standards prescribed by the Ordinance of the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Each research facility institution must include one-third of the committee members who have “no conflict of interest.” Based on the amended APA 2012, the IACUC appointment framework has been upgraded: appointments are now for 2-year terms and require a qualification certificate from a training course for animal protection organized by the Director of the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency. The training began in 2008 and about 14,000 members completed the course as of December 2013. While the APA requires a minimum of three members of IACUCs, the LAA requires a minimum of four members, a person with a Ph.D. degree in laboratory animal science and experienced in same fields in addition to aforementioned IACUC membership (Table 1). It should be noted that both laws limit a maximum of 15 members, including a chairperson. During public hearings on the governing of animal use and care, representatives from the animal welfare and protection advocacy group took part in the regulation process of the APA, so the revised law reflects the suggestion on its committee composition requiring one member recommended by the national animal welfare and protection organizations accredited by the government agency. There are 15 animal welfare and protection organizations in Korea, as of September 2013 (Animal Protection & Welfare Division 2014). Table 1 summarizes the regulatory requirements on composition and qualifications of the IACUC in Korea.

Term Of The Unaffiliated And Nonscientific IACUC Members

The term of “no institutional conflict of interest” used in the 2008 APA may be interpreted as a person who is not affiliated with, and has no financial interest in, the animal facility institution. The scope of “institutional conflict of interest” in the APA is defined by the Ordinance of the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, and they are (1) an individual or his/her spouse who has been employed by the animal facility institution within the last 3 years, (2) an institutional official or his/her spouse who has an immediate family relationship, (3) a person or corporate official who owns over 30 % of the investments of the animal facility institution, (4) a person or corporate official who has a business contract with the animal facility institution, and (5) a corporate official or staff who is otherwise affiliated with the animal facility institution.

Table 1. Composition and qualification of the Korean IACUC

Table 1. Composition and qualification of the Korean IACUC

In the USA, appointment of an unaffiliated member was introduced in the 1985 Animal Welfare Act Amendment and the 1985 Health Research Extension Act (Haynes 2010) as a compromise between external regulation of the use of animals in research and professional voluntary self-regulation (Haynes 2010; OTA 1986). The National Institutes of Health Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare recently redefined the requirements of the nonaffiliated member to represent the general community interests in the proper care and use of animals. The nonaffiliated member must not be (1) a laboratory animal user or former user, (2) affiliated with the institution, or (3) an immediate family member of an individual affiliated with the institution. Immediate family includes parent, spouse, child, and sibling (NIH Guidance Notice Number: NOT-OD-15-109, 9 June 2015). In Korea, it is enough that the person is not affiliated with the user institution but possible for the unaffiliated member and the nonscientist member to be the same person. The unaffiliated member is usually chosen from people who are likely to be cooperative with the review process and not by a public vote or by a comprehensive search for members of the public willing to serve (Haynes 2010). The lay member, which is the term often used in the UK and Canada, may or may not be the same individual as the unaffiliated member.

Role And Value Of The Unaffiliated And Nonscientific Members Of The IACUC

Professor Haynes (2010) stated that the role of the unaffiliated member of the IACUC is to ensure that the interests of the animals used in research are not compromised by decisions made by animal users and the institutions that support them, when there is a conflict of interest. The unaffiliated member can be acting as a liaison between the public and the institution, bringing a different perspective to the research institution. The US PHS Policy gives no criteria that should be applied during the selection of this person nor indication of what the role of this person should be, while the Animal Welfare Regulations 9 CFR 2.31 state that it is intended that the “person will provide representation for general community interests in the proper care and treatment of animals” (Haynes 2010). In Korea, the role of the unaffiliated member and nonscientific member is not addressed at all as it is in the USA, while the role of community representatives on Animal Care Committees in Canada is to work with the other members of the committee and with the institution to ensure appropriate animal care and use within the institution (CCAC-CFHS 2006). The benefit arising from the participation of community members and nonscientists acting as liaisons for animal protection groups is careful monitoring, aimed at preventing the inhumane use of animals. Although Korean regulations do not directly address the role of the unaffiliated members, committee composition requiring one member to be recommended by a national animal welfare and protection organization implies that this person may be representing the interest of the animal welfare and protection community and advocating for the animal research subjects. The unaffiliated member is usually chosen through nomination/recommendation by the NGO devoted to animal protection and welfare activities and among the personnel who have completed training prescribed by the government official, the Director of the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency.

There are many countries, including Canada, Australia, Sweden, and the USA, where representation of wider community interests is a requirement for such committees; some additionally specify a representative from an animal welfare organization (RSPCA 2014). In the beginning stages of applying the Korean law, the APA 2008, most of unaffiliated members recommended by the NGO are mostly active members of animal protection groups or ethicists, philosophers, lawyers, and members of clergy, but there is much frustration in practice. There are few experts or educated IACUC members in this field. Thus, the interpretation has been modified in practice, and the Korean law has been revised to allow a choice to be made by the institution of the veterinarian whose presence is already required on the committee. The unaffiliated person could have a science background, such as a veterinarian from a different institution who can share the general values of research scientists. A survey analysis of the overall membership composition of IACUCs at leading US research institutions found that the concept of the committee member who has “no institutional conflict of interest” is skewed by large numbers of members appointed from the institution (Hansen et al. 2012). The nonscientific person could be someone who shares the general values of researchers (Haynes 2010) and the public concerns, and conversely it does not hold that a scientist could not represent public interests, but it is usually interpreted to mean just that (Hansen et al. 2012). Ethical review should aim to ensure that, at all stages of any scientific work involving animals from initial planning to completion of the studies and review of the outcomes, there is adequate, clearly explained “ethical justification” for use of the animals, which is subject to ongoing critical evaluation (RSPCA 2014).

Guidance And Training For The Unaffiliated And/Or Nonscientific Members

All personnel involved in the care and use of animals must be adequately educated, trained, and/or qualified in basic principles of laboratory animal science to help ensure high-quality science and animal well-being (Greene et al. 2007). The IACUC members must take personal responsibility for ensuring that they have the skills and knowledge to perform their duties, applying ethical consideration (Choe and Lee 2014). A training program for the new IACUC lay members and a continuing education program should be offered as an opportunity to learn various aspects of the IACUC process appropriate to specific kinds of protocols. The conduct of animal use in research implicates a variety of ethical concerns pertaining to such values as dignity and welfare, and these ethical concerns have been translated into a complex regulatory apparatus, containing specific ethical/legal provisions concerning such matters. Unfortunately, they are to be considered to be a burden, aggravated by the difficulties of comprehensive information retrieved. The technical language in the protocol review by a committee member who has a nonscience and non-research background may obscure both the ethical issues and the science involved in the research proposal. Without understanding the experimental design, it is difficult to review what the point of the protocol is. A wide diversity of people come from a variety of disciplines and fields of work, within or outside establishments in which laboratory animals are kept and used (Smith and Jennings 2009). However, there is little guidance for the unaffiliated IACUC member about how they are supposed to perform their role, and there are often no training opportunities. Based on the experience, most IACUC members may not possess the expertise that is required to perform an efficient yet effective review on the proposed topic of study.

In the USA, most institutions are adopting “The Guide” and the “Principles for the Use of Laboratory Animals” as a basis demonstrating their commitment to responsible animal care and use and good science (AAALAC 2014). The Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative Program at the University of Miami is providing different courses for IACUC members to meet the US Department of Agriculture and Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare requirements for basic training in the humane care and use of animals. In 1986, Canada published a guide for lay IACUC members entitled CCAC-CFHS Manual for Community Representatives, and A Resource Book for Lay Members of Ethical Review Processes was produced by Smith and Jennings of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, UK (Smith and Jennings 2009).

The two Korean laws governing animal use for scientific purposes have been revised a total of 11 times over the last 6 years (Choe and Lee 2014). Both regulatory agencies, i.e., the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, provide regular training based on the legal requirements. The training course conducted by the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency consists of four programs, with a total duration of 4 h, targeting mainly IACUC members who need the initial qualification certificate which is mandated by law. Findings through an Internet search on current training curricula and types of training programs conducted by two Korean governing regulatory agencies, have shown that there is no appropriate training program or guidebook offered for the nonscientific and unaffiliated IACUC members on how to perform their role and evaluate the relationship between animal protection regulations and the ethical treatment of animals.

Opportunities And Future Improvements

The welfare of research animals, quality of scientific data, and institutional reputation significantly depend on the assurance that the people managing and overseeing research animal care are adequately trained and qualified. The responsibility for animals used in research in Korea still depends on the hands of the researchers, and the quality of animal care and animal welfare varies tremendously among research institutions. Researchers in the USA have found that even within the same school or institution, research laboratories are inconsistent in their animal care policies and standards of care (The Guide, p24). When organizing a training program designed solely for unaffiliated and nonscientific committee members, the content of the program should be modified accordingly to ensure that the participants represent a diversity of backgrounds and perspectives. Such a program could focus on the general ethical principles, the roles and responsibilities of members, and the process of protocol review.

The number of protocols reviewed by the IACUCs varies among institutions. The limit on the maximum number of IACUCs permitted by law causes a burden on the workload of individual IACUCs and affects the quality of the protocol review. Future progress and development of guidance and training based on their role and experiences will carry real possibilities for added value and should be beneficial. Developing national guidelines will assist institutions and researchers in planning and conducting research in accordance with humane and ethical principles.

Based on the findings and experiences from the current practice of the unaffiliated and nonscientific IACUC members, potential future improvements might include the following: (1) continuing and refresher training should be provided; (2) a guidebook for unaffiliated and nonscientific members should be developed; (3) a separate training program, including key elements involved in the ethical review process and how to carry out an effective literature search on the 3Rs’ alternatives to meet the requirements of the IACUC review, should be considered; (4) advanced courses based on each laboratory animal species should be developed; (5) quality and consistency of the ethical review outcomes should be assessed; and (6) active encouragement by government and institutional authorities could enhance the quality of training curricula.

On 29 January 2015, the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs announced the 5-Year Plan for Animal Welfare to live harmoniously as human and animals with nature. There are three core tasks on companion animals, farm animals, and laboratory animals. Its action plans on laboratory animal welfare are (1) to develop national standard of animal care and use guidance, (2) to enhance quality assurance of the IACUC, (3) to ban animal testing on cosmetics, and (4) to stop animal experiments in the undergraduate school if validated nonanimal alternatives are available.

The authors have developed a new Korean guidance on efficiently and effectively finding information on the 3Rs based on the EURL ECVAM Search Guide of the European Commission. This guide sets out a step-by-step search strategy which provides detailed instructions for those with a nonscientific background.

The authors have also developed a website and library (www.bicstudy.org), to share expertise and support resources to demonstrate bridging experts’ advice and quality education.

Conclusion

The promotion and protection of the laboratory animal is one of the core competencies of well-educated personnel involved in the use of such animals. Unlike human research subjects, the role of the IACUC requires members to be knowledgeable on different laboratory animal species. The main areas for future improvements in animal care and use practices must be considered in the context of the objectives of the experimentation and different research animal species. Institutional responsibilities for providing a framework should be to ensure that the 3Rs are actively developed and applied at all stages of the research process. It is a shared responsibility among all those involved in research including government, institution, and individual personnel, to promote and disseminate related information for future improvements. A future challenge is to implement a user-friendly guidebook for unaffiliated IACUC members, based on international standards, guidance, and personal experiences through a complex interplay of regulatory objectives and public opinion.

Bibliography :

- Animal Protection & Welfare Division, Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. http://www.animal.go.kr/aec. Accessed 12 Nov 2014.

- Association for Assessment and Accreditation of laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC). http://www. aaalac.org/accreditedorgsDirectorySearch/aaalaclistall. cfm. Accessed 12 Nov 2014.

- Bioethics Information Center Study. bicstudy.org. Accessed 12 Nov 2014.

- CCAC Canadian Federation of Humane Societies. (2006). Manual for community representatives. Animal Care Committees. Rev. 2006. Ottawa: CCAC-CFHS; http://www.ccac.ca/en_/assessment/acc/resources_acc. Accessed 12 Nov 2014.

- Choe, B. I., & Lee, G. H. (2014). Individual and collective responsibility to enhance regulatory compliance of the three Rs. BMB Reports, 47(4), 179–183.

- Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI Program, 2014). https://www.citiprogram.org/index.cfm?pageID=91 https://www.citiprogram.org/citidocuments/forms/Animal%20Care%20and%20Use%20(ACU)%20Catalog.pdf. Accessed 12 Nov 2014.

- Greene, M. E., Pitts, M. E., & James, M. L. (2007). Training Strategies for Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) members and the Institutional Official (IO). ILAR Journal, 48(2), 131–142.

- Hansen, L. A., Goodman, J. R., & Chandna, A. (2012). Analysis of animal research ethics committee membership at american institutions. Animals, 2, 68–75.

- Haynes, R. P. (2010). Animal welfare: Competing conceptions and their ethical implications (p. 50). Gainesville: Springer.

- Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidebook pp24. Mench, J. A., et al. (1991). Institutional animal care and use committees: Who should serve? ILAR News, 33(1–2), 31–37.

- National Academy of Sciences. (2011). Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (p. 220). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- OTA (Office of Technology Assessment), U.S. Congress. (1986). Alternatives to animal use in research, testing and education. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, OTA-BA-273.

- Reed, B. T., & Jennings, M. (2008). Promoting consideration of the ethical aspects of animal use and implementation of the 3Rs. AATEX, 14(Special Issue), 131–135.

- (2014). http://science.rspca.org.uk/sciencegroup/ researchanimals/ethicalreview/ethicscommittees/laymembers. Accessed 12 Nov 2014.

- Smith, J. A., & Jennings, M. (2009). A resource book for lay members of ethical review processes (2nd ed.). Horsham: RSPCA.

- Rebecca, D. (1999). Community representatives and non-scientists on the IACUC: What difference should it make? volume 40, Number. http://ilarjournal. oxfordjournals.org. Accessed 20 Dec 2014.

- Schapiro, S. J. & Everitt J. I. (2006). Preparation of animals for use in the laboratory: Issues and challenges for the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). 47(4). http://ilarjournal.oxfordjournals.org. Accessed 20 Dec 2014.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.