This sample Children and Ethics Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Specific biological, psychological, and social factors have been recorded throughout history as affecting the vulnerability of children. Taking these factors into account, the bioethical values of beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, and autonomy are developed. The backbone of bioethics is respect for human dignity and human rights which necessarily include children’s rights.

Introduction

Bioethics rose in the nineteenth century to answer to ecological problems of technology and medical ethics in practice. With human research analyses, bioethics has included the main values of autonomy, beneficence, and justice (Nuremberg Code, Belmont Report, Declaration of Helsinki, Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights). The United Nations proclaimed the Universal Delaration on Human Rights in 1949 and the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 and recognized that human rights are of a great relevance for children, since their specific biological factors and their social relationship define them as a vulnerable group who needs protection, with special focus on their dignity. Vulnerability of children may represent a contradiction or a complementarity factor in the recognition of their human dignity and partial autonomy. So justice has different meaning for this dependent group.

History Of Childhood Representation

The definition of children has changed with the historical evolution of societies from the view of a “little adult” to a vulnerable child (Ariès 1960). This important change in the representation of children started with philosophers like Locke in England (theory of “tabula rasa” which considered the mind at birth like a “blank slate” (Goodyear 1999)) and Rousseau in France (children are separate beings and autonomous with their own needs). During the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, the general concept with the influence of French revolution is that children deserve human rights as human beings and that they need both protection and progressive empowerment for a full citizenship into adulthood. Medical doctors changed their view and started to study biological and functional specificities of children one century later.

Though there were 200 years between the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Man, 1789, and the International Convention on the Rights of the Child of 1989, the statement that followed seems conceptually odd. The main principles of the convention were the right to a healthy psycho- physical development free from hunger, abuse, and neglect. The convention sets that children are neither the property of their parents nor objects of charity; they are human beings and they are subjects of their own rights and responsibilities appropriate to their age and stage of development, complying with human equality and justice (Waterston und Goldhagen 2006).

The concept of vulnerability (UNESCO 2013) of children still has a great influence in medical culture and explains the paternalism of the physician-pediatric patient relationship. Protection is associated to the obligation of the physician to act in the patient’s best interest without considering the patient’s preferences :. From the same concept of vulnerability and null/partial autonomy, the recognition of parents’ autonomy and their right to information about their child does not represent an obligation that information is given to the child, particularly in situations of distress. The values of autonomy and right to full information for children have been developed in North American bioethics, and they are still a matter of discussion in Europe and other regions.

Conceptual Clarification/Definition

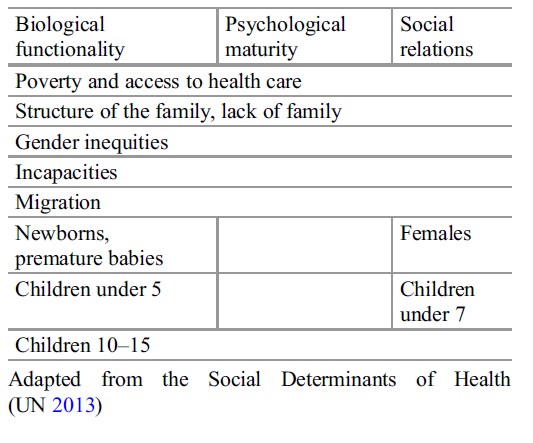

Vulnerability. The end of childhood is legally defined as the age of majority or adulthood, from 15 to 21, with 18 being the most common, as reported by (UNICEF 2014). The differences in children’s vulnerability are based on psychological maturity, biological functionality, and societal relations (Table 1).

Societal Relations. As for adults, poverty is a major factor of vulnerability as it is related with poor access to formal education, health services, and violence. Poverty reinforces gender inequities: early marriages, multiple pregnancies, more probability for sexually transmitted infectious diseases, and violence. In this context, children need more protection to assure that the cycle of poverty is not repeated. All factors are more profound when children present dependency because of some incapacity. Each of these situations represents a violation of the values of human dignity, equity, and justice.

Table 1. Factors of vulnerability in children

Table 1. Factors of vulnerability in children

Biological Functionality. There is a consensus that the vulnerability of newborns and infant mortality is an ethical problem as well as a biological one. The United Nations has adopted the Millenium Development Goals for reduction of infant mortality in all countries (United Nations 2013) complying with the value of beneficence and the duty of protection and justice. Medicine has tried to fight with this problem and diffusion of appropriate technology has reduced mortality in the majority of countries. The few results obtained in some countries associate infant mortality with poverty, lack of access to health care or insufficient health programs for women, gender inequities, and augmentation of adolescent pregnancy. Recently it has been described that all these factors confront the values of equality and dignity of humans and the right to health care and to education (both formal and sexual educations).

With newborns, premature neonates represent a more vulnerable group; they deserve bioethical reflections regarding their specific problems. World Health Organization and medical organizations divide premature babies in two groups: those born between 26 and 36 weeks of gestation and extreme premature births born at less than 25 weeks of gestation. With the current level of science, the fetus cannot live before 20 weeks of gestation and it would be considered as an abortion. The ethical problems are mainly present for the extreme premature babies and newborns with congenital illness or defects with poor survival or poor quality of life for survivors.

The concept of “quality of life” is a holistic one which takes into account all determinants of health (social and biological) for an independent, personal, and social interaction of the individual. More and more research on development of premature babies has shown both early and late consequences associated with extreme premature births. There is no consensus about saving life versus medical futility (medical actions without perspective of success, Halevy und Brody 1996) for medical decisions for extreme premature babies or newborns with severe congenital defects/diseases, and life or death decisions are left to parents in countries with Protestant majority. Doctors are more paternalistic in Catholic and Asian countries as well as in developing countries by using their “medical privilege” (privilege of knowledge and power for decision, as defined by Bostick et al. (2006). More studies on pathophysiologic changes with and without medical interventions in extreme premature cases are needed; studies of cultural/religious behaviors are important for bioethics recommendations. In developed countries and some developing countries, prenatal programs include the detection of abnormalities, considering them an indication for abortion. But in the majority of countries, abortion is not permitted and screening for these diseases occurs after birth. Ethical values of non-maleficence, care, and justice arise in every clinical decision concerning these children.

Another aspect of survival of premature babies with developmental sequels or newborns with congenital malformation is that many countries suffer from an insufficient specialized infrastructure that is needed for medical interventions, as well as the affordable costs of these interventions for the family. An insufficient infrastructure may lead to total dependence with or without emotional interaction. Although there may be discrimination against these children, groups that give support to the children and their families are of great importance. When the family is not well structured, the child may be abandoned; charity organizations or the government who work to promote justice should care for them. When the family has to deal with caring for a family member who is ill, often the mother has to abandon her work, which often creates new ethical problems between beneficence and justice.

Children Under Five

This group has great physiological and developmental changes. The children depend on health knowledge, parental cohesion, and economic capacity of the family for their survival. Distribution and access to health care, and particularly to immunization programs, is important. Mortality in this group is still high and lessoning rates in this group has been described in the Millennium Development Goals (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2013). From a bioethical perspective, protection through health policies is widely recognized, and all children have the right to be raised in a warm and loving family as part of the global community where health and wellbeing occurs. Education for progressive autonomy has to be started from early age, taking into account the needs of each stage of development as cuoted by UNICEF (2014). A holistic multidisciplinary approach recognizing both the vulnerability and the dignity of these children will permit their full development.

Children 10–15 Years Old

Adolescence is usually determined by the onset of puberty and physical, psychological, and behavioral changes in the child. The Convention on the Rights of the Child defines adulthood at 18 years old, and so do the majority of countries. At the same time, in some countries, national laws recognize marriage of girls from 14 and working age from 15. So, the end of adolescence and the beginning of adulthood varies by country and by gender, and even within a single nation-state. Studies of cognitive development and processes of medical decision-making have shown that youth at the age of 15 differ little from young adults in their early 20s in how they make these decisions. On these bases, the notion of a “mature minor” has been developed by North American bioethicists: adolescents have the rights to decide for themselves as they have the required maturity to do so unless they have no legal rights (Coleman und Rosoff 2013).

Psychological Maturity And Social Relations

Autonomy And Development

The works of Piaget and Kohlberg have shown how children reach their maturity and autonomy. The age of seven has been the starting point for this in the historical development of societies, when children end their mothers’ protection to enter school. Topics about the concept of assent in for ethical research have been introduced to recognize this process, and it is the right of children to know what it will be done with them and their approval of this act is needed from age 12 (CIOMS 2002). But this assent is limited by the right of the parents’ consent to decide about participation. In clinical practice, it is an ethical obligation to give information for the consent/ assent of the child and his/her parents about the invasive procedures, the disease, and the treatment. However, not all doctors and bioethicists agree with this and some propose the age of 12 equivalent of starting adolescence for assent/ consent. In many developing countries, children leave school at this age and enter working life or married life. Working life is associated to poverty, poor access or lack of access to school, and lack of familiar structure. When countries or families resolve the problem of poverty, education starts to be a priority, transforming the life of children for autonomic development.

Societal Relations

The major social problems are the following:

Drugs: affecting primarily adolescents, its use affects social relation favoring self-isolation and victimization or, on the contrary, participation in gangs. Drugs are associated with violence and augmentation of death in adolescents, particularly boys.

Adolescent pregnancy: it may discriminate two groups from 15 to 18 in countries where social culture recognizes maturity of adolescents to create a family and when it is an autonomous decision of girls and from 10 to 15 when it represents a violation of her dignity, as she is not mature enough to decide and pregnancy represents a biological stress. For both groups, early marriage means abandonment of education; this may favor poverty, lack/loss of self-estimation, more vulnerability, and poor quality of life.

HIV/AIDS: WHO has reported an augmentation of HIV infection in young adults of developing countries, which means that transmission occurred during adolescence. As with adolescent pregnancy, it is the result of poor/lack of sexual educational programs with children after 7 years of age and with youth, with the basis emphasized on their needs and behaviors. In the realm of bioethics, it is important to hold consensual discussions and about how all partners (adolescents, their families, physicians, legal representatives) benefit from HIV/AIDS research. In fact, where these programs are developed, they are based on the recognition of dignity of children and autonomy of adolescents, including respect for confidentiality and privacy, communication, and dialogue.

Ethical Dimension

The ethical values necessary for attention of children will be considered in the order of their appearance in history of medicine and with the teachings of Hippocrates. They may be applied in different contexts such as home settings, social relations, hospital settings, and research settings as they constitute the bases for reflection about ethics problems.

Beneficence: “In The Best Interest Of The Child”

Beneficence is the cornerstone of medicine and human consideration of children. In fact it represents the recognition by society of the rights of the parents to raise their children from the point of view of the best interest of the child (Dwyer 2008). But the evolution of the understanding of child’s development and reports of child abuse have shown the recognition of the limitations of this viewpoint and the legalization of parents’ obligations for the protection of the children through national and international laws.

Beneficence and best interest of the child are determined by parents’ values and beliefs and may affect the child’s health and dignity: for example, selling girls for marriage and a “better life,” or refusing health interventions in the name of religion, and beating a child for his/her “education.” Studies have reported the impact of physical, psychological, and sexual violence on children throughout their life if they cannot receive special psychological attention. All kinds of violence violate all bioethical values of beneficence/non-maleficence, protection of vulnerability, and justice, as all the values of human rights and children rights, equity, liberty, and dignity.

Medical doctors also claim that they work for the best interest of their patients, but they forget that children are not only a vulnerable biological individual but also a human being with beliefs and behaviors in a family context. The value of respect of children’s dignity means information, discussion, and informed consent in each individual case (UNESCO 2005). It is particularly important in such situations as: premature births, severe congenital diseases/defects, chronic diseases, family dysfunctions, and sexual education. In this way, formal educational programs are more and more centered to the needs of children’s development within the family and the society. Pediatricians and family doctors have developed health programs centered to the family and the child (Vargas-Rubilar and Arán-Filippetti 2014). Both programs are based on the value of beneficence, recognizing that “self-esteem and autonomy of children comes from being cared for, loved, and valued and feeling that they are part of a social unit that transmits and interprets values, communicates openly, and provides companionship and connection to the world” (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009). Bioethics has to take into account this relation as well as the diversity in the composition of families. In all countries the proportion of children who live in poverty is higher for female-headed families than for conventional structured or extensive families. Social and public policies have not kept up with these changes and with the consequences of actual economic crisis, leaving families alone to cope with this situation. Bioethics may encounter pediatric promotion of family and child-centered care that involves them in the decisions for the health care of the child through an active partnership.

Two other problems arise from the development of genetics and pharmaceutics. The first one is the treatment of rare congenital diseases. Actually the cost of treatment of these diseases is extremely high for the family, the insurance companies, and the public health system. The society has few discussions around the bioethical questions of beneficence/justice/autonomy/distributive justice/non-maleficence. Where families are more organized, they help each other and nongovernmental organizations also support, but in many developing countries, they have to cope without this support. What will be the answer from a bioethics standpoint? The second problem is the development of biobanks for the conservation of umbilical cord blood. Parents are deciding for their newborn child in the name of his/her best interest as science offers many perspectives of diagnosis/treatment. But the guaranties for honesty or responsibility of biobanks are not always secure, because the problems of privacy and owning are matter of inquietudes. Clear, complete, and honest information about the objectives, investments, and responsibilities are needed to answer to the best interest of children.

Non-maleficence

“Do not harm” needs to be absolutely ligated to beneficence. It is generally so, but the development of medical technology has produced some confusions.

The first problem is confronted by decisions of “saving a life”: when doctors and family are in front of a child whose death is imminent and there is scientifically no possibility of reversibility, new actions or prolongation of actions may represent futility, and until doctors proclaim that they act from beneficence, the consequences are “maleficent” from utilitarian view. Societal culture, beliefs, and behaviors will determine the course of possible decisions as cuoted by Lago et al. (2007). Some countries have allowed euthanasia in newborns and children (see above). Others prefer the concept of “not doing” that means no extraordinary measures of actions, letting the natural course of dying. Both options give an important meaning to the term palliative care: inclusion of the family for quality of care during the last moments of life.

In addition pain has not been extensively studied in children, and many doctors are reluctant to use treatment since all drugs have negative effects and they have not been investigated in small children and newborns. Beneficence is discarded in the name of non-malevolence (not favoring drug addiction). This attitude may favor a confrontation with the parents or the child himself/herself. It is necessary to discuss this problem and to benefit from more investigations on drugs for pain.

Autonomy: Dignity And Self-Development

The development of a child’s capacity to critique a situation is relatively slow and subject to the adult orientation (family, teachers, medias). Some research is in course about the influence of the Internet and social media on children and adolescents. This situation represents a conflict between two values: beneficence as protection of children and liberty of information and autonomy. Who can make the decision: parents as legal and moral representatives of their children or the state as representative of the society? This problem is still subject of bioethical and legal debates.

Informed consent is the formal recognition of the capacity of a person to decide after a rational analysis of the offered information. The respect due to children dignity reinforces the importance of informed consent proportional to the child maturity and capacity of understanding. As children are dependent on their parents, the legal figure is of surrogate consent of the parents for their child. This position is in accordance with the value of beneficence and “best interest of the child” as presented before with the same related problems. There is consensus that before the age of 7 (in some areas, 12), one acts in the interest of the child, and yet it is more and more common to give the child information as well. Another point is presented for adolescents: if their capacity of decision-making is recognized for their current life, decisions about work, or responsibility of a family, why cannot they consent for their health? The American Academy of Pediatrics (2009) proposed that physicians obtained “parental permission and assent for the adolescents, respecting parental authority and recognizing its limitation associated to the individual dignity of the child.”

In some countries, sexual health programs are accepting adolescent consent on the bioethical base of the human value of dignity (human rights), the medical deontology of respect of confidentiality, and the utilitarian theory which promotes the best issues for the greatest group (in this case it means prevention/attention of pregnancy and/or sexually transmitted diseases).

Most of western and Latin-American countries agree with the rule of 7 years to choose assent or informed consent for minor patients both in clinical research and in routine medical care: children and youth 7–14 years of age should be asked to assent to interventions and receive basic information about the proposed care, its risks, and potential benefits, and in youth 15–18 years, the process should be very similar to seeking informed consent from young adults (American Association of Pediatrics 2009). Discussions about the pertinence of “informed assent” rose while questioning the capacity of rationalized decisions of children under 18 and the legal rights of the parents. For some bioethicists, it is not honest to ask the child for his/her assent when we know the legal limits of such a question. For the majority of bioethicists, WHO and UNESCO, the process of informed assent is necessary, as it represents recognition of the child’s dignity and specificity and a participation of health-care professionals in the construction of self-autonomy of the child. The process of assent/consent reinforces the confidence of the child and his/her family with the doctors and health team in the clinical relationship.

When a child refuses to participate in a research, there is a consensus to accept this refusal. It is important to investigate the causes of this refusal (beneficence and protection). In clinics, a child may refuse to know the truth about his/her disease, and no one can obligate him/her to listen to non-desired information. The majority of bioethicists consider that in case of emergency care, it is not necessary to ask for their desires, but it is essential to comply with the values of beneficence and non-maleficence and with the information to the family (AAP 2014). When a child after seven refuses to participate in his/her treatment, the case has to be evaluated by a bioethics committee with him/her and his/her family for the best solution.

Life-Threatening and Life-Limiting Conditions. The value of honesty is a cornerstone of some bioethicists for the information of fatal diseases and death. But this position is directly associated to culture and legal obligations: where individual liberty is a fundament of social consensus, such information is generally delivered to the child with/without his/her parent’s agreement. Their position is that withholding information may stimulate the child’s imagination about worse scenarios and deepen their distress. In countries where the value of protection and care of the child are the bases of the society, bioethicists, medical doctors, and parents are more cautious and this kind of information is adapted to individual cases. For them, the prioritized right is maintenance of hope, and honesty is present in the information of his/her parents. It is a consensus in all countries to elucidate the patient’s values and preferences and to take into account the concept of spirituality/religiosity for the attention of chronic/ fatal illnesses.

Justice: Social Recognition And Equity

All rights implicate duties. Bioethicists are working with pediatric associations and organizations for the rights of children to a family, equal opportunity for development and education, proportional autonomy, opinion about their life, and defense against all types of abuse (UNICEF). The cornerstone values of this position are equity of human beings and justice. These values have been present for the development of programs for children by United Nations organizations, governments, and civic organizations for children. The codes of ethics represent examples of this recognition: The Code of Medical Ethics of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association (2009), the Code of Ethics for Early Education. The Code of Conduct on Child Labor has been developed by the Southern African Development Community, and protective law for child labor has been adopted in Bolivia. Both countries had to take into account the needs of the children and their dignity in a context of poverty. The measures taken by the governments were substantiated by the utilitarian theory of lessoning damages, responsibility for protection, and recognition of the dignity of the children. These measures are against the international recommendations against child labor, but they take into account the desires of children in national situations. The Tourism Child Protection Code of Conduct is an instrument of self-regulation and corporate social responsibility, which provides increased protection to children from sexual exploitation in travel and tourism. The initiative has been endorsed by the United Nations-World Tourism Organization (UN-WTO), many national governments, and private companies.

Conclusion

Children’s participation in decision-making is part of their empowerment for self-autonomy, but it is also necessary to take into account its complexities: evolution of dependency and maturity as well as family and external factors. Health-care settings have an important duty for this participation, since people aspire to live in the absence of disease since it disrupts the normal development of children. Health-care personnel need to understand the main values of bioethics and human rights for their daily work with children. Bibliography :

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Bioethics, (2009). Policy Statements: Appropiate Boundaries in the Pediatrician-Family-patient Relationships: Managing the Boundaries. Retrieved June 27, 2014, from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/contente/124/6/1685.full

- American Medical Association, Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs Code of Medical Ethics (2014). Retrieved June 24, from http://www.ama-assn. org//ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/codemedical-ethics

- Bostick, N. A., Sade, R., McMahon, J. W., & Benjamin, R. (2006). Report of the American Medical Association Council on Ethical and judicial affairs: withholding information from patients: rethinking the propriety of therapeutic privilege. The Journal of Clinical Ethics,17(4), 302–306. 27 July 2014.

- Coleman, L. D., & Rosoff, P. M. (2013). The legal authority of mature minors to consent to general medical treatment. Pediatrics 131, 786. Originally published online 25 Mar 2013. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2470. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/ content/131/4/786.full.pdf

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), (2002). International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, ISBN 92 9036 075 5. http://www.cioms.ch/ images/stories/CIOMS/guidelines/guidelines nov 2002 blur b.htm

- Dwyer, J. G., (2008). Book review of the best interests of the child in healthcare. Faculty Publications. Paper 1509. Retrieved from http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1509

- Edwin A.K., 2008, Don’t lie but don’t tell the whole truth: the therapeutic privilege is it ever justified? Ghana Medical Journal, 12(4), 156–161. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC2673833/pdf/GMJ4204-0156.pdf

- Goodyear, D. (1999). John Locke’s pedagogy. In M. Peters, P. Ghiraldelli, A. Zarni, C. Gibbons, & R. Heraud (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of philosophy of education (pp 1–6). Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia, Marilia, Brazil and Auckland, New Zealand

- Halevy, A., & Brody, B. A. (1996). A Multi-institution collaborative policy on medical futility. JAMA, 276(7), 571–574. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.#32$03540070067035. Retrieved from http://jama. jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=406788

- Lago, P. M., Devictor, D., Piva, J .P., & Bergounioux, J. (2007). End-of-life care in children: The Brazilian and the international perspectives. Journal de Pediatria (Rio J), 83(2 Suppl), S109–116. Retrieved from http:// www.jped.com.br/conteudo/07-83-S109/port.pdf

- (2005). Universal declaration on bioethics and human rights 19 October 2005. Retrieved March 17, 2013 from United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, documents web site: http:// portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=31058&URL_ DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

- (2013). Report of the international bioethics committee of UNESCO on the principle of respect for human vulnerability and personal integrity 2013. ISBN 978-92-3-001111-6. Retrieved May 6,2014 from United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, documents web site: http://www. unesco.org

- (2014). Protecting children updated: 19 May 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2014 from United Nations Children’s Fund, Web site: http://www.unicef.org/crc/ index_protecting.html. Accessed 5 June 2014.

- United Nations. (1949). The universal declaration of human rights. Retrieved March 17, 2013 from United Nations, documents web site: www.un.org/en/docu ments/udhr/

- United Nations (UN). (2013). Convention on the rights of the child adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by general assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. Retrieved March 17, 2013 from United Nations, documents web site: http://www.ohchr. org/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/crc.pdf

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, (2013). The millennium development goals report 2013 (pp. 64). UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. ISBN: 978 -92-1-10128 4-2. Retrieved March 17, 2013 from United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs web site: https://www.unfpa.org/public/publications/pid/6090

- Vargas-Rubilar, J. & Arán-Filippetti, V. (2014). Importancia de la parentalidad para el Desarrollo Cognitivo Infantil: una Revisión Teórica. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Nin˜ ez y Juventud, 12(1), 171–186. 15 June 2014 (Spanish).

- Waterston, T., & Goldhagen, J. (2006). Why children’s rights are central to international child health. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 92, 176–180.

- American Board of Pediatrics. (2013). Bioethics bibliography Ethics Committee. 8 July 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014 from American Board of Pediatrics, Web site: https://www.abp.org

- Ariès, P. (1960). El niño y la vida familiar en el Antiguo Régimen. Retrieved from http://201.147.150.252:8080/ xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/1346/Texto%2015. pdf?sequence=1 (Spanish).

- Harrison, C., Kenny, N. P., Sidarous, M., et al. (1997). Bioethics for clinicians: 9. Involving children in medical decisions. In Singer, P. A., Bioethics for clinicians, Series. University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 156(6). 6 June 2014.

- Rousseau, J-J. (2004). Emile. Retrieved from Free Ebook The Project Gutenberg EBook www.gutenberg.org/ ebooks/5427

- Yeong Cheah, P., & Parker, M. (2013). Consent and assent in paediatric research in low-income settings BMC Medical Ethics 2014, 15, 22. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-15-22. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6939/15/22

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.