This sample Chronic Illness And Care Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Being chronically ill implies the management and treatment of a disease for a long time and even possibly for the rest of the affected person’s lifetime. Chronic health conditions or illnesses most commonly include diabetes, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, hypertension, and/or cardiovascular conditions. Since the ethical arguments concerning chronic illness, on the whole, center around the unfair distribution of resources, the argument will be advanced that this issue can only truly be addressed by national and/or regional policy changes and individual complementary obligations exist where patients should be encouraged to accept responsibility for their own health and not being solely dependent on a system to assist them in their functioning. This entry focuses on the following aspects: background with regard to chronic illness and the healthcare systems (internationally), ethical issues in long-term care focusing on care, and the distribution of resources, followed by an argument that individuals should take responsibility for their own healthcare.

Introduction

According to a report from the WHO (World Health Organization 2005), chronic illness has been a major challenge for healthcare systems.

The report explains that chronic illness is the leading cause of disability and mortality world-wide accumulating to approximately 63 % of all deaths and 43 % of the global burden of disease. It is estimated that half of all currently required healthcare worldwide is due to chronic illness and that the burden of such care will increase. Chronic illnesses account for more or less 47 % of the total burden of illness in the eastern Mediterranean region and 80 % of all deaths in low and middle-income countries worldwide (World Health Organization 2005). With approximately 20 million Americans suffering from asthma, 5 million from congestive heart failure, 26 million from depression, and 21 million from diabetes, collectively these four chronic illnesses amount to $149 billion in direct costs and $286 billion in total costs annually (Shortell et al. 2009) resulting in about 10 % of the US national health expenditure (World Bank 2015).

Other than presenting society with fiscal challenges, the treatment of a chronic illness also places high demands on patients (Nes et al. 2013) such as the daily confrontation with restrictions, discomfort, treatment regimens, and complex self-management activities that can potentially impact significantly on their quality of life and psychological well-being. Roland et al. (2005) argue that care for chronically ill patients is often characterized by misdiagnoses, suboptimal treatment, and failure to implement primary and secondary preventive measures purely as a result of limited fiscal and human resources.

The rapid aging of populations and greater longevity, in both developed and developing countries, result in the increased prevalence of chronic diseases (National Institute on Aging 2007). The alarming growth in the number of individuals with chronic conditions and the failure of healthcare systems and organizations to meet the needs of these individuals have resulted in the prioritization of disease management in policy-making healthcare reforms. Most developed countries (as defined by the World Bank) provide some degree of universal health coverage (UHC) to address the needs of those most in need.

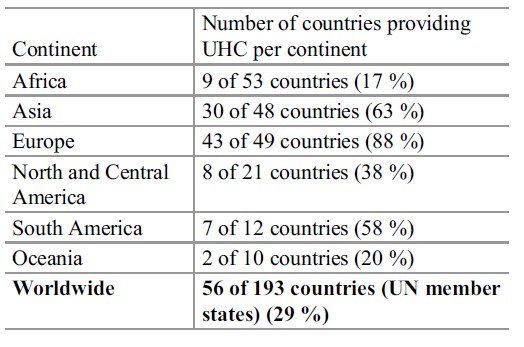

Table 1. Summary of the international prevalence of universal health coverage per continent

Table 1. Summary of the international prevalence of universal health coverage per continent

The term universal health coverage has gained popularity in the past decade; however, little consensus exists on its precise definition. Bump (2010) identifies at least two general meanings, where the first refers to the notion that everyone should have health insurance, while the second implies that medical services should be available at either low cost, no cost, or at least a context where the system ensures these benefits. Regardless, the implementation of UHC could be done in various ways with the architect invariably being the state to ensure access to the service; the state dictates who gets access on which basis (legislation) and assures minimum standards (regulation). Generally, UHC is funded by means of tax-based revenue. Table 1 provides a summary of the international prevalence of universal health coverage per continent (adapted from Stuckler et al. 2010).

Bump (2010) identified seven key aspects that should be addressed during the implementation of universal health coverage; these aspects are similar to those identified in the WHO report on chronic illness and will be addressed later in this entry:

- Who bears what responsibilities in the system?

- What rights are to be guaranteed to whom?

- How ought limited resources to be distributed across unlimited demand?

- Should all have equal access to services?

- How are needs to be identified and determined?

- What are the goals of the system? Should it refer to a process or a policy to implement change?

- Not being able to deliver everything to everyone, should there be a trade-off between the breadth (universality) and depth (service) of the coverage?

While taking cognizance of human rights and minimum responsibilities of any state, resources will always be limited and its rationing will constantly be at the heart of issues such as who gets healthcare provision and who should go without. Despite its clear practical advantages, the strategies for providing UHC, especially for long-term care, have generally remained low on many government agendas with 71 % of countries not having introduced any UHC strategies (see Table 1). In 2002 the WHO conducted a study where they found that little has been done to address healthcare challenges such as minimizing the prevalence and increase in chronic illness. Taken the aforementioned statistics into consideration, one could conclude that the world at large has not succeeded in addressing the issue in the years which have followed which could potentially result in dire consequences for future generations. One consequence which may result from states’ inaction and/or unwillingness to address the issue of the growing number of those becoming chronically ill can be the inability of the state to provide proper care for its citizens and consequently burdening only a few with the task of taking care of the ill. This inappropriate distribution of risks and benefits is a significant burden on those who need to take care of the ill.

In one of the most influential contributing studies, even though it was conducted over a decade ago, titled “Ethical Choices in Long-Term Care: What Does Justice Require?” (WHO 2002), the authors extrapolated data to argue that in many developing countries, specifically those with already existing universal health coverage in some form or another, the need for long-term care of those with chronic illnesses will increase by as much as 400 % in the coming decades. The rationale of their argument lies in the following:

- There is a salient change in the global demographics with a rise in the aging populations who are more susceptible to chronic illness.

- Changing dietary and lifestyle habits that are associated with the rise of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and stroke.

- General chronic health challenges.

Because of these changes and the alarming increase in people with chronic illnesses, two major ethical questions are raised against the background of the aforementioned questions as postulated by Bump (2010). These questions concern who should care for those with chronic illness and who should get treatment within a context of limited resources (fiscal and human resources).

The next section will be dedicated to addressing the ethical challenges as identified in literature concerning chronic illness. However, since the argument on the whole revolves around the unfair distribution of resources (as will be illustrated), especially human and fiscal resources, the argument will be advanced that these issues can only truly be addressed by national and/or regional policy changes – which clearly may take decades to effect. In addition, this entry will conclude in disseminating the idea of collective and individual complementary obligations where patients should be encourage to accept responsibility for their own health and not being solely dependent on a system to assist them in their functioning.

Ethical Issues In Long-Term Care

Care

The influential WHO report (2002) contends that existing systems of distributing the burdens and benefits of caring for the chronically ill and disabled are often unfair. In addition, inequity is likely to intensify taking into consideration factors such as demographic and population changes. Traditionally the burden and responsibility of care is usually placed on female members of the community/family. As such, the report suggests that the ethical dilemma of unfair discrimination and allocation of burdens could be addressed by redefining care giving as gender-neutral. Traditional societies (located mainly in developing countries) should be invited to discuss the changes in the module of care with specific attention to equitable, fair, rational, and transparent decisions about long-term care without any discrimination against vulnerable groups (women in specific).

In an attempt to address the change in caring, which is inevitable given the demographic changes taking place internationally, a Moorean metaphysical Utopia would hold that all members of society should get care, regardless of resources (i.e., respecting autonomy) and that no unnecessary burdens should be placed on anyone else (i.e., beneficence). However, according to Moore, a society like this can only exist if there is agreement among its members regarding what is important and what is not. In this regard, healthcare ethics at large hold that society has a moral imperative (a principle compelling people to act) to care for all its citizens with greater emphasis on those who are not able to adequately care for themselves, especially the marginalized and vulnerable (children, elderly, ill). However, Fischer et al. (2012) indicate that the vulnerable is a medically underserved group who are more likely to have poorly controlled chronic illness but who are also more likely to experience barriers in accessing healthcare. In addition, chronic disease management strategies that focus only on clinic visits hold further challenges of accessibility for these patients.

Another increasingly important care context is that many young people (i.e., young adults) tend to migrate regionally from rural areas to urban areas and even across international borders. Migration has a positive influence on reducing poverty and also for helping those who stayed behind to have a better quality of life (with money being sent home) where this may help to pay for medical care and even enable the family to access running water and electricity (Alonso 2011). However, because of this migration pattern where the younger members of families move away, the elderly usually stay behind without caregivers.

Limited Resources: A Case For Justice

The second general argument concerning ethical issue pertaining to chronically ill individuals is that the projected exponential increase in the number of chronically ill people who will also be surviving longer due to advances in medical therapies to control illnesses will inevitably add to the competition among patients for limited resources. Often, in the wake of limited resources, the argument of who the resources get allocated to is usually based on a utilitarian principle where the greater good of society trumps the greater good of individuals. One such approach is to provide preferential treatment to members of society who have the greatest potential to be productive. However, if allocation is purely based on the argument of utility (i.e., productivity), there is no room left to consider patient rights as advocated by the deontological notion of the human rights movements that justice requires inherent respect for persons, not merely for their productive capacity.

Justice, according to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, is the most important virtue of any just society, where any social institution (such as a government) ought to ensure that the loss of freedom for some is not justified by a supposed greater good shared by others. Justice, according to virtue ethics, holds that beneficence is paramount to a well-functioning society and that there should be a balanced outcome of risks and benefits for all agents involved. In addition, beneficence is in line with the modern human rights perspective which holds that it is undesirable (i.e., immoral in terms of the culture of human rights) to allow that the sacrifices (risks) imposed on a few can be outweighed by the larger sum of advantages (benefits) enjoyed by many; this constitutes the basic criticism of deontology against utilitarianism. Taking the aforementioned into consideration, the principle of justice, as seen from a human rights perspective, may therefore not be subjected to political bargaining or even unfair discrimination, but should be regarded as one of the liberties (freedoms) of equal citizenship.

Although the aforementioned is a principle that all of society should aim for, the reality is that there are limited resources. The prominent moral philosopher concerning justice, John Rawls (1999), argues that the only condition in which society may be allowed not to respect justice is when an injustice is tolerable only when it is necessary to avoid an even greater injustice. However, Rawls himself agreed that the aforementioned argument will only be permissible in a society where all agents had equal access to all the benefits of citizenship. Sadly, this condition is globally found wanting to a larger or lesser degree, thereby highlighting the importance of continued dialogue in the hallways of policymaking.

Conclusion

Authors such as Fisher and Dickinson (2014) argue that basically two problems have slowed the global drive and ability to improve chronic disease care. The first problem is that the current model of primary healthcare delivery focuses mainly on occasional, acute care and does not comprehensively address the ongoing needs of patients with chronic disease, especially those who require continuous monitoring and ongoing coordination of care among specialists and general practitioners. The second problem is that the chronically ill have a high prevalence of chronic comorbid conditions which are generally associated with poor disease management and high accumulative costs.

As the problem of care on the one hand is a complicated logistical problem for any society (WHO 2002), it is also, most emphatically, an ethical problem, a problem that must be addressed not only with resourceful and creative policy development but also with critical, reflective, and normative thinking in a context of multiple and sometimes conflicting ethical principles. The pursuit of efficiency in healthcare is an ethical issue because, at its heart, it is seeking to minimize avoidable distress, disability, and death. In addition, it is about making sure that a finite amount of resources are deployed against an infinite amount of needs in a way that ultimately maximizes health gain (Rice and Smith 2001). However, the only way in which the issue of limited resources (care and fiscal) can be adequately addressed is if those who are chronically ill are firstly adequately educated and guided to understand and manage their illnesses and, secondly, made aware of the dangers of comorbidity and how to effectively self-manage their chronic diseases.

Self-care management has become the mantra of chronic disease management; it focuses on education programs for those who are ill to take active responsibility of their own illnesses, manage it in a responsible manner, and get engaged in tertiary prevention to prevent any (further) comorbidity. These patients are instructed and supported firstly by a hands-on qualified (professional) team who provides education in the form of accessible information and support and secondly by unqualified (lay) teams in the form of support groups. Self-care management, according to Soleimani et al. (2010), has been shown to reduce disability and improve patients’ quality of life. They also found that, specifically from a policy and practical viewpoint, an emphasis on the patient’s inherent abilities has contributed positively to reduce victim blaming, state control, and paternalism.

The ethical solution to the issue of chronic illness and care is not to depend on policy changes per se, as these may take decades to effect, but rather to take individual responsibility for one’s own actions and to manage the chronic illness in association with medical professional and support groups, respectively. Although patients will always have individual rights which need to be duly respected, they also have corresponding individual responsibilities which are derived from the Kantian principle of autonomy; the Kantian definition of patient autonomy holds that an individual’s physical and psychological integrity ought to be respected and upheld by society. Furthermore, the principle of autonomy also acknowledges the human ability to self-govern and to have the ability (competence) to voluntarily choose a course of action from different alternative options. In other words, an autonomous, competent patient should assert some control over the choices which may direct their healthcare. Consequently, with this application of self-governance and free choice come a number of responsibilities for which the healthcare system cannot solely be held responsible, but in which individual patients need to actively participate through self-care management.

Bibliography :

- Alonso, J. A. (2011). International migration and development: A review in light of the crisis. CDP Background Paper No. 11(E) ST/ESA/2011/CDP/11(E). http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/cdp/cdp_background_papers/bp2011_11e.pdf. Accessed 24 Mar 2015

- Bump, J. P. (2010). The long road to universal health coverage: A century of lessons for development strategy. Seattle: PATH and the Rockefeller Foundation.

- Fischer, H. H., Moore, S. L., Ginosar, D., Davidson, A. J., Rice-Peterson, C. M., Durfee, M. J., MacKenzie, T. D., Estacio, R. O., & Steele, A. W. (2012). Care by cell phone: Text messaging for chronic disease management. The American Journal of Managed Care, 18(2), e42–e47.

- Fisher, L., & Dickinson, W. P. (2014). Psychology and primary care: New collaborations for providing effective care for adults with chronic health conditions. The American Psychologist, 69(4), 355–363. doi:10.1037/ a0036101.

- Nes, A. A. G., Eide, H., Kristjansdottir, O. B., & van Dulmen, S. (2013). Web-based, self-management enhancing interventions with e-diaries and personalized feedback for persons with chronic illness: A tale of three studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 93, 451–458.

- National Institute on Aging. (2007). Why population aging matters – A global perspective. Bethesda: National Institute on Aging.

- Rawls, J. (1999). A theory of justice. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Rice, N. J., & Smith, P. C. (2001). Ethics and geographical equity in health care. Journal of Medical Ethics, 27, 256–261. doi:10.1136/jme.27.4.256.

- Roland, M., Dusheiko, M., Gravelle, H., & Parker, S. (2005). Follow up of people aged 65 and over with a history of emergency admissions: Analysis of routine admission data. BMJ, 330(7486), 289–292.

- Shortell, S. M., Gillies, R., Siddique, J., Casalino, L. P., Rittenhouse, D., Robinson, J. C., & McCurdy, R. K. (2009). Improving chronic illness care: A longitudinal cohort analysis of large physician organizations. Medical Care, 47(9), 932–939. doi:10.1097/ MLR.0b013e31819a621a.

- Soleimani, M., Rafii, F., & Seyedfatemi, N. (2010). Participation of patients with chronic illness in nursing care: An Iranian perspective. In A. Acton (Ed.), Issues in nursing research, training, and practice. Atlanta: Scholarly Editions.

- Stuckler, D., Feigl, A.B.., Basu, S., & McKee, M. (2010). The political economy of universal health coverage. Background paper for the global symposium on health systems research. UNSPECIFIED. Geneva: WHO.

- World Bank. (2015). Health expenditure, total (% of GDP). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS. Accessed 21 Mar 2015

- World Health Organization. (2002). Ethical choices in long-term care: What does justice require? Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2005). Preventing chronic diseases. A Vital Investment: WHO global report. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Adler-Milstein, J., Sarma, N., Woskie, L. R., & Jha, A. K. (2014). A comparison of how four countries use health IT to support care for people with chronic conditions. Health Affairs, 33(9), 1559–1566. doi:10.1377/ hlthaff.2014.0424.

- Benatar, S., & Brock, G. (2011). Global health and global health ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berlan, D., Buse, K., Shiffman, J., & Tanaka, S. (2014). The bit in the middle: A synthesis of global health literature on policy formulation and adoption. Health Policy and Planning, 29, 23–34. doi:10.1093/heapol/czu060.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.