This sample Clinical Bioethics Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

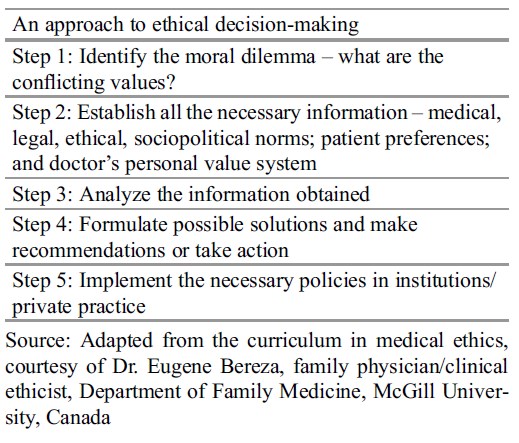

Health-care providers face many important and challenging ethical dilemmas in their work environments on a daily basis. As professionals, they are accountable for their decisions to patients and their families, professional bodies, employers, and colleagues. Consequently they must be able to justify their decisions or recommendations. Clinical ethics refers to decision-making and reflection about the best choice(s) to make in the delivery of health care. In attempting to resolve ethical dilemmas in clinical practice, the conflict between two or more equally important but competing values must be identified, and the ethical dilemma must be articulated. This is an important starting point. Gathering as much data as possible is the next critical activity. Seeking medical information about the patient’s condition, prognosis, and alternatives is important. In addition, relevant health law, patient and family preferences :, value systems of health-care workers, and the sociopolitical context must be explored. Engaging in ethical analysis using theories and principles is important. Finally, a decision is reached in collaboration with the patient and/or family, and policy is developed to facilitate decision-making in the future. Following a systematic process of data collection, reflection, and deliberation is essential. If, after this process, a decision cannot be reached, consultation with a clinical ethics committee is often necessary.

Introduction

Medicine is a profession. It is a profession because of its commitment to serving the public so that patients derive the maximum benefits of health. Previous generations of doctors committed to ethical conduct have earned the profession trust in the eyes of society. In order to maintain the professional reputation of medicine, it is essential that each new generation of doctors understands the ethical obligations that members of the medical profession incur. These obligations are not simply the rules and codes of conduct laid down by professional bodies. Each member of the health team needs to take responsibility for his or her own performance and the performance of colleagues. Inculcating a sense of professionalism drives doctors and other health professionals to deliver high standards of care. It is on this basis that patients are willing to place their trust in the health-care profession.

Responsibility in health care therefore implies that doctors and the health-care team be held accountable for their decisions and actions. In other words, we need to justify all our decisions – clinical and moral decisions alike. A body of ethical theory assists with such justification.

History And Development

In the fourth century BC, Hippocrates, philosopher and physician, known also as the father of Western medicine, addressed important ethical questions in health care. The Hippocratic Oath, which is regarded as the first written document pertaining to the ethical practice of medicine, was written of this oath was the concept of “primum non nocere” or “above all, do no harm.” Approximately 2500 years ago, the ancient Greek philosophers – Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle – debated questions about morality. These questions about morality still trouble us today: What does it mean to live a good life? What does it mean to be a good doctor? What is right? How do we know it is right? What is justice?

Globally, different philosophical systems have raised similar questions. African philosophy, Confucian ethics, Buddhist and Hindu philosophy, and Middle Eastern philosophies have all posed fundamental questions about the meaning of life.

Metaethics is a field of ethics that studies and develops theoretical approaches to solving ethical problems. Much of the theoretical development in ethics started with broad-based universal ethical theories grounded in Western philosophy (Beauchamp and Childress 2001). The ancient Greek philosophers as well as philosophers in Africa, China, India, and other countries have made enormous contributions to the development of a theoretical basis for ethics. Over the centuries various philosophers have attempted to answer these perplexing questions, and the field of ethics is firmly situated within the discipline of philosophy. The systems of moral reasoning developed by these philosophers are referred to as ethical theories.

Medical care has traditionally been based on the principle of primum non nocere or “above all, do no harm.” In 1803, British physician, Thomas Percival, published the first medical ethics book in which he described the doctor’s main obligation as doing good and avoiding harm, rather than giving in to the patient’s requests.

In the 1960s the invention of the Scribner shunt for renal dialysis and the first heart transplantation by Professor Christiaan Barnard raised new ethical questions in health care, namely, distributive justice and the definition of brain death. Since then further technological advances in the health sciences have brought with them new and more complex ethical questions. Changing relationships between health-care professionals and the pharmaceutical industry have raised important new ethical questions. Complex relationships between the health-care profession and medical funders raise ethical questions around patient confidentiality and justice on a regular basis.

Since the 1980s, the emergence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has surfaced new challenges in clinical ethics. Issues of disclosure and risks to third parties have challenged conventional notions of confidentiality.

In the twenty-first century, natural and man-made disasters have raised questions globally about the duty to care and the duty to rescue.

Ethical Dimension

Ethics

Ethics has been defined in various ways over time. The World Medical Association (WMA) defines it as follows: “Ethics is the study of morality – careful and systematic reflection on and analysis of moral decisions and behaviour, whether past, present or future” (Williams 2009). Using this definition, morality refers to the value dimension of human decision-making and behavior. In discussing morality, the following words are frequently used: “rights,” “responsibilities,” “virtues,” “good” and “bad,” “right” and “wrong,” and “just” and “unjust.” Ethics refers to what we ought to do in a particular situation. Hence, ethics is a matter of knowing what the right thing is to do, while morality is a matter of doing the right thing.

Ethics is a large and very complex field of study as it deals with all aspects of human behavior and decision-making. Bioethics deals with the moral issues raised by developments in the biological and health sciences at a more general level. Ethics in medicine explores the responsibility of the doctor and members of the health-care team in their roles as professionals providing care to patients.

Clinical Dilemmas

Health-care professionals encounter challenging clinical and ethical questions on a regular basis. Clinical dilemmas arise when there is uncertainty about the best treatment option to use in a patient with a specific health problem. Such dilemmas are resolved using evidence derived from sound research in clinical medicine. Ethical conflict arises when one has to choose between two or more equally important but competing values. Rational moral reasoning and analysis guide decision-making when ethical dilemmas like these arise:

Could a doctor refuse to treat an HIV-positive patient?

Can confidentiality be breached to protect a third party?

Is a medical receptionist obliged to maintain

confidentiality of patient information?

Is withdrawing medical care doing good or causing harm?

Should a request for assisted suicide be granted?

How do we respond to impaired colleagues?

All health-care professionals ought to think critically about ethical issues. It is necessary to reflect on values and belief systems – religious or secular. Engaging in debates on moral issues is healthy – building arguments to justify an ethical viewpoint or decision is essential. Knowing one’s responsibilities and professional obligations is crucial. Furthermore, it is the responsibility of all health-care workers to be aware of the laws that govern the practice of medicine. While clinical ethics and health law are distinct disciplines, significant overlap exists. In resolving ethical dilemmas consideration of morally acceptable laws is imperative. The law alone, however, is inadequate to resolve all ethical challenges in medicine. This is so because the law changes from time to time and from one country to another. In some instances there is no legislation to justify clinical decisions. Consider the challenges in the field of HIV/AIDS – under such conditions we are guided by the principles and theories in ethics. It remains the responsibility of all health-care professionals to be familiar with the law and to incorporate legal considerations into ethical deliberations.

Today we follow a more patient-centered holistic approach in health care, and respect for patient autonomy is a more dominant principle. The four principle approach developed in the United States is based on four common basic moral principles – respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Ethical dilemmas often involve conflict among these principles (Gillon 1994). The dominant principle that emerges in decision-making may depend on various factors. Along with other theories like consequentialism and deontology, the four principles may be regarded as a principle-based theory. Although controversial and by no means a complete moral system on its own, the four-principle approach provides an analytical framework that assists clinicians to organize their thoughts around many of the ethical problems encountered in clinical practice. These principles, although controversial, provide a culturally neutral approach to considering ethical dilemmas.

In the course of medical practice, one is bound to encounter several clinical situations that pose ethical dilemmas. The nature of such cases will vary from mundane to highly complex. Clinical ethics explores the application of theory to a clinical/ethical dilemma using a structured stepwise approach. The framework is intended to serve as a guide to assist in resolving ethical dilemmas in clinical care.

Consider the following case:

Annie is 14 years old. She was admitted to a tertiary government hospital and was transferred to the high care unit of the obstetric ward. Two days prior to the admission, Annie delivered a baby girl at a secondary hospital. She had a traumatic vaginal delivery and sustained cervical and vaginal lacerations. As a result, she had a massive postpartum hemorrhage. The lacerations were sutured in the theater and she was transferred to the tertiary hospital where she arrived in grade 3 shock. Resuscitation commenced with Voluven and Ringer’s lactate. Annie had a hemoglobin of 3.3 g% and was stable. The obstetricians were of the opinion that a blood transfusion was indicated. Her mother refused the transfusion as the family subscribes to the Jehovah’s Witnesses (JW) faith. Annie had not yet been baptized into the faith. What should the treating clinician do? (Moodley 2011

Step I: Identify And Articulate The Moral Dilemma

As a starting point, it is important to understand what a moral dilemma is. Beauchamp and Childress (2001, p. 10) describe moral dilemmas as “circumstances in which moral obligations demand or appear to demand that a person adopt each of two or more alternative actions” without being able to perform all the required alternatives. In this case the alternative actions are either to administer a lifesaving blood transfusion or to choose a risky option of alternative fluid replacement that might not work and result in the death of a young patient. The choice is between saving a young life on the one hand and respecting a religious belief on the other hand that might result in the death of a young patient. Respect for autonomy conflicts with beneficence and non-maleficence. If the refusal of a blood transfusion is respected, will the treating clinicians cause more harm than good especially if the 14-year-old mother Annie dies?

Step 2: Establish All The Necessary Information

Prior to embarking on an ethico-legal analysis of this case, it is important to establish all the necessary scientific and medical information related to the case.

Scientific And Medical Information

General Questions To Pose

- Is this a medical emergency and is the blood transfusion indicated?

- What are the alternatives to blood transfusion and is there evidence to support the use of alternatives?

- Why did Annie have such a traumatic delivery at the secondary hospital? A vaginal delivery may be assisted with an episiotomy and forceps or vacuum extraction.

Specific Questions

- If Annie went into cardiac failure during the night, would a transfusion be indicated?

- In a public hospital, is she entitled to expensive alternatives with respect to blood replacement such as Hemopure?

- If the patient refused a blood transfusion, should she occupy a high care bed?

- Is the baby healthy?

- Would an independent opinion contribute to resolving the clinical dilemma?

Legal Considerations

- What laws will influence your decision? In this case we have to take cognizance of health legislation and the age of consent. Annie is 14 years old and hence in some countries would be in a position to accept or decline medical treatment. In other countries this may not be the case. Is a blood transfusion regarded as medical treatment? If Annie develops cardiac failure, the blood transfusion will be regarded as lifesaving medical treatment. Can the parents deprive their child of this treatment based on religious grounds? (McQuoid-Mason 2005). In some countries the child’s right to life is of paramount importance. Legal precedent has been established by case law in some countries where the High Court has ruled in favor of transfusing children against parental religious wishes in two cases – one case involved a baby and the other a 12-year-old girl. Legislation in some countries defines a child as being less than 18 years old.

- How old is the father of the child? Is this a case of statutory rape? Does the father of the child have any rights to his child in this case?

- Have rules of the professional body been violated?

- From a legal perspective are there grounds for civil action against the hospital if the girl is transfused?

Ethical Considerations

- What is the ethical standpoint? How do the four principles interact? Here we consider autonomy versus non-maleficence/ beneficence. Is the patient (Annie) making an autonomous decision or is she under the influence of her mother? It could be argued that her competence to consent is impaired by the emotional stress of her traumatic delivery and the coercive influence of her mother. Is her refusal truly informed given that the consequences of her refusal could include death and permanent separation from her child? If it can be argued that the young girl cannot make an autonomous decision to refuse the blood transfusion, then beneficence will override autonomy. The relevant principles must be balanced against each other.

- How do the ethical theories impact on this case? We ask whether a universal ethical theory such as consequentialism can influence a decision to treat especially when the consequence could include death. Were the outcomes considered at the outset and was the greatest good for the greatest number achieved?

The consequences of transfusion are as follows:

Positive Consequences

- Annie’s life will be preserved.

- She will make a quicker recovery.

- Her baby will have a mother.

- The bonding process will be enhanced.

- Breast-feeding can be established.

Negative Consequences

- Her parents may be treated as outcasts in the JW community.

- The doctor may face legal sanction.

The consequences of not transfusing could be:

Positive Consequences

- Parents will be embraced by the JW community.

Negative Consequences

- Cardiac failure and death of a teenager.

- Depriving the baby of its mother (if the mother dies).

- Prolonged hospital stay with risk of nosocomial infections (if the mother survives).

- Delayed bonding with the baby.

- Higher costs of alternative iron replacement such as Hemopure.

Using a deontological approach, the treating doctors could argue that it is their duty to preserve life, and this creates an obligation to transfuse the patient irrespective of the outcome. All doctors set out with a duty to do good and provide the best level of care possible.

What about virtue ethics? What would the good doctor do? A good doctor would act with honesty and integrity. This would preclude administering the blood at night, for example, and deceiving the parents.

Casuistry or case-based reasoning is a useful theory as many cases have set legal precedent around the world. In many cases the children were in life-threatening conditions. Refusal of blood for babies and children under 12 years of age by parents was overridden by the courts in most cases. In this case Annie is 14 years old, not herself a baptized JW, and she is not as yet in a life-threatening situation.

- What are the patient’s preferences 😕 Annie has articulated her preference not to have a blood transfusion. However she is also very uncertain and traumatized after the delivery. She is constantly under the influence of her mother who sleeps in the ward and watches over her and the medical staff day and night.

- What does your personal value system dictate?

Usually, this will influence the final decision significantly. These value systems may be influenced by medical education, parental influence, political affiliations, religious beliefs, and personal experiences.

- What are the sociopolitical norms of the day?

Are they acceptable? How will they influence medical decision-making? In countries with a firmly entrenched human rights culture, autonomy is emphasized.

Step 3: Analyze The Information

Considering all the information gathered in step 2, one will go through a balancing process in which the various components are assigned different weights. It is important to confer different weighting to the principles. Respecting patient autonomy does not mean that doctors must do exactly what patients request all the time. The obligation of informed consent created by the principle of respect for autonomy requires a thorough consent process to occur between doctor and patient. An inadequate consent process invalidates the weight carried by the principle of autonomy and tips the balance in favor of beneficence – that is – acting in the best interest of the patient.

In addition, different approaches to the core problem may be used and different outcomes examined. This process will culminate in the development of moral arguments to justify the position eventually defended. Well-constructed premises using logic and rationality will lead to rational conclusions.

Step 4: Formulate Solutions, Make

Recommendations, and Then Act In this step possible solutions should be considered, recommendations are made, and one then acts on the decision. Possible solutions include:

- The development of a treatment protocol for Jehovah’s Witnesses patients who decline blood transfusions. Such a protocol will include procedures that must be followed in emergency situations as well as nonemergency elective procedures.

- For emergencies accessing urgent legal guidance may be required especially where the clinician decides to override patient autonomy. This is of special importance where minors are concerned.

- In elective, nonemergency situations, the establishment of a counseling team to consult with the patient before a final decision is taken is important. Consulting with colleagues is usually helpful. The involvement of the hospital Jehovah’s Witnesses representative regarding the use of alternative forms of fluid replacement may be necessary.

- Development of a comprehensive consent document for competent adult patients to read before declining lifesaving treatment.

- Sourcing of or making a video to provide patients with information on the surgical process to be followed and the use of alternative forms of fluid replacement.

Step 5: Implement Policy

Policy may have to be implemented, created, or amended in a medical institution such as a hospital as well as in a private medical practice. Any policy development will be based on how the case was handled in the end. Guidelines may have to be drawn up so that the management of a similar problem in the future is much clearer. These guidelines can be incorporated into the standard operating procedures of the clinic or practice.

Table 1.

Table 1.

What Happened In The Above Case?

Annie and her mother were counseled. They continued to refuse the blood transfusion. The ethics consultant was of the opinion that Annie’s competence to consent was questionable due to her emotional distress. The teenage pregnancy could have disempowered her in terms of her ability to negotiate her treatment preferences : with her mother. If Annie went into cardiac failure, it would have been necessary to override the parental decision and transfuse.

Until such time use of Hemopure (bovine hemoglobin) could continue as there was a donated supply of six units of Hemopure on the hospital premises. Hematinics and fluids continued for 2 weeks. On day 14 postdelivery Annie’s anemia due to blood loss had improved. She and her baby were discharged.

Conclusion

In this case it was fortunate that an alternate expensive intervention was available at a state hospital. If this were not the case, it may have been the parent’s responsibility to pay for the alternate treatment or remove their daughter to private care. Fortunately, the patient did not go into cardiac failure. If she had, it may have been necessary to obtain a court order and transfuse her against the wishes of her parents. Ethical decision-making can be challenging at the best of times.

The approach outlined above is intended as a guide to the decision-making process. It may need to be amended on a case-by-case basis.

Bibliography :

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gillon, R. (1994). Medical ethics: Four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ, 309, 184–188.

- McQuoid-Mason, D. (2005). Parental refusal of blood transfusions for minor children solely on religious grounds-the doctor’s dilemma resolved. SAMJ, 95(1), 29–30.

- Moodley, K. (Ed.). (2011). Ethics, law and human rights: A South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

- Williams, J. R. (2009). World Medical Association Medical ethics manual. Ferney-Voltaire: World Health Communication Associates.

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2009). Principles of biomedical ethics (6th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jonsen, A. R., Siegler, M., & Winslade, W. J. (2010). Clinical ethics: A practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine. New York: McGraw Hill Medical.

- Lo, B. (2013). Resolving ethical dilemmas: A guide for clinicians (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.