This sample Common Good Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

In a globalized world, the bioethical decision-making process is becoming more and more complex. Pluralism and cultural diversity have to be taken in account. This entry explains the different positive and negative conceptions of common good by examining its history, its resurgence, and its possible future as a platform of values that could be agreed upon by everybody on certain conditions.

Introduction

In a globalized world where nation-states have less power to decide alone and where science and technology in the health field are moving faster than ever, it has become necessary to ask ourselves how to think ethically about moral issues, about individual versus collective obligations. In a context where social and economic issues have become global, unequal access to public health and health care or to research and innovations is still the case in many countries. The possibilities offered by personalized medicine or by the enhancement of human nature have influenced the dialogue between physicians, health professionals, and patients. Interdisciplinary discussions between social and life sciences are now essential at the global level. Men and women have always been preoccupied by “others” who were the tribe, the family, the community, and the city. Normality was defined by the traditions, the laws, and the behaviors of these entities. Now “others” are all the individuals living in our global village in different cultural and religious contexts. This global environment questioned our way of thinking about bioethics and the challenge before us is: How can we live together, how can we talk about a common good approach in such an environment where values, principles, and codes of conduct are different and where individual interests are the strongest way of acting in many countries? These questions form the foundations of the actual debate about the possibility of using a global common good perspective to tackle moral issues. But what is common good? What are the ethical values and principles behind that concept?

History And Definition Of Common Good

Although bioethics issues are becoming more and more global, the possibility of having or not being able to have a common platform of values to make moral judgments is an important part of the conversation on bioethics.

Common good is now frequently mentioned, without any definition, in bioethics when health and health care policy, beginning of life and end of life, allocation of resources, genomics and genetics issues are discussed either from a moral, legal, social, economic, or political perspective. It is also discussed in education, business, climate change, and poverty. This lack of definition raises important challenges for bioethical inquiry.

Two Interesting attempts at defining common good are suggested by (Velasquez et al. 1992) referring first to John Rawls who defined the common good as “certain general conditions that are.. .equally to everyone’s advantage” and to the Catholic religious tradition that defines it as “the sum of those conditions of social life which allow social groups and their individual members relatively thorough and ready access to their own fulfillment”. Those definitions have led to many conversations about what they really mean: Who is going to specify the “conditions” or the “advantages” needed to attain their own fulfillment of individuals? Those definitions raise the importance of deciphering texts that mention common good to see what values and principles are referred to when this concept is mentioned. For example, in bioethics, that definition can be related to the welfare state which gives the state an obligation to support all the individuals in a given society or community. But how far do they have to go to meet this commitment?

History tells us that common good is a concept grounded in philosophy and already put forward by Aristotle, Plato, and Thomas Aquinas. Many Christian thinkers imagined universals “in which the good, the true, and the beautiful existed as eternal and unchanging forms [.. .]. For centuries, morality in the West was defined as following eternal rules, which could be applied to different circumstances” (Baldacchino 2002, p. 26).

From the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries, secular versions of the common good appeared and the monolithic approach lost credibility. During that period, the literature on common good flourished with different viewpoints being expressed about its meaning by philosophers and economists like Hobbes, Rousseau Locke Hume, Smith Kant Bentham Mill Keynes, Hayek Friedman, and Rawls. Their writings offer a broad panorama about the meaning and the tensions between individual and collective good (Stanton Jean 2011). With the development of bioethics, their work has put its imprint on the vision of thinkers writing about ethics and bioethics who use their views to justify their own theories about moral, ethics, and bioethics. Sophie Mappa stated that tracing the historical depth of the issue of the common good and the general interest of its effectiveness and its impasses, demonstrating the move of some meanings of the old order of things in the new, their mutation, the emergence of new meanings and differences in the definition, the complexity of factors that are associated with the meanings of the common good, and the general interest and the difficulties of their implementation, is an endeavor that has an interest not only speculative but also fundamentally political (Mappa 1997, p. 12).

A Renewed Perspective On Common Good

Common good conception has in the last century found a new life, with the development of an environmental agenda that includes the responsibility of individuals and society in assuring the welfare of future generations in a sustainable development perspective. Gradually this point of view has reached life sciences and bioethics. This vision differs from the one based on public interest, where it belongs to the governments to decide what is in the interest of the population. Thus, today the moral, social, communitarian, and humanistic common good vision defended by some bioethicists is not a norm but the product of a conversation between responsible people. That conversation does not presuppose a fixed moral doctrine but a contextualized application of principles taking into account pluralistic economic and sociocultural contexts. This vision can be seen as the appropriate one in a globalized world where “Globalization, differs from universalization at least in two points. First, it covers all human beings actually exiting and second, future human generations” (Gracia 2014, p. 27).

The link between common good and globalization has often been mentioned in international organizations. For example, Koichiro Matsuuara, then the director general of the UNESCO said in 2000: “It is UNESCO’s duty to sound the alarm about the dangers of globalization and constantly to recall the need for equality of access for all to what some call the ‘common’ good [.. .] Globalization is today generating uncharted challenges calling for new norms or ethical principles – or even regulatory mechanisms with which to guarantee the continued exercise of universally recognized human rights” (UNESCO 2000).

This moral and humanistic approach of common good as the foundation of our actions could then permit nations to work together in a global community, and it could be argued that the global common good perspective proposed in bioethics is entrenched in a social and humanistic approach. Based on this vision, several authors are wondering if we should not give new vigor to the concept of common good. These authors want to search in philosophy, law, sociology, political sciences, and bioethics a renewed vision of the concept of common good. This vision would take into account plurality and cultural diversity and be enshrined in Human Rights and Human Dignity to allow “moral strangers” to work together as “moral friends” in “social institutions, within which, albeit in limited ways, common goods can be pursued and health care policy framed” (Engelhardt 1996, p. 11). Such an approach would permit to protect individuals as well as communities.

Jobin (1998) emphasized that the common good is, first, the normative articulation of actions/interests individuals or collective within a larger intersubjective body. Second, the concept of common good involves a methodology to define the configuration of this articulation between actions/interests (p. 131). How to articulate the configuration between individual and collective interests is the foundation of the actual debate in bioethics about the possibility of using a global common good perspective to tackle moral issues. But what is common good? What are the ethical values behind that concept? As common good is almost never defined, it is by reading texts that mention it that it becomes possible to relate it to a set of values.

Who would have thought that this notion, although included in the Christian theological heritage, but long neglected, would find new letters of nobility to think the complexity of the possible injustices caused by these health systems? (Graziaux and Lemoine 2006). Such a vision could permit one to move away from an inflexible definition imposed by religion, ideology, nature, nation, or market. This conception of a global common good perspective is based on the belief that although there are different ways of thinking about a question in a multicultural world, humanity is composed of interdependent people that must show a strong degree of solidarity to survive.

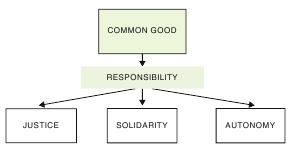

One possible way of achieving this goal is to use a global common good perspective. There are contradictory opinions about that. On one side, common good is seen as a Western and Christian concept that cannot be exported to different cultures. Some philosophers and bioethicists argue that it is impossible to reach a global agreement on common good because of the different nations or groups now included in the discussion like nations, women, aboriginals, and religious groups. On the other side, there is a current trend that proposes to revitalize the common good perspective. A review of the literature shows that although common good is almost never precisely defined, it is possible to identify the values and principles that are mentioned by the proponents of this global vision. The most often mentioned are responsibility, justice, solidarity, and autonomy (Stanton-Jean 2011).

Those four concepts can be used in a global environment where different cultures are called to work with each other. Why? Because they encourage people to pay attention to each other (solidarity) without letting go their own capacity to decide (autonomy). They also call for just and equitable legal systems (justice) and to pay attention to future generation (responsibility). So a conceptual model for global common good could be illustrated as shown below (Fig. 1):

Indeed, a thorough review of the literature permits one to believe that the concepts of justice, solidarity, and autonomy can form the foundations of the concept of responsibility that unites all three and offer a platform to use when we talk about global bioethics. Within this framework responsibility means looking at the future consequences of our actions and their impact on future generations. It represents an ethics concept resting on the three pillars of justice, solidarity, and autonomy. Solidarity provides the vision to think globally about the others whether the other is in our country or in another part of the world. Although autonomy is a fundamental principle in bioethics, it has its limits imposed by solidarity, justice, and responsibility. This model can generate by induction a vision of a global common good perspective.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of a universal vision of common good (Stanton-Jean 2011)

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of a universal vision of common good (Stanton-Jean 2011)

There will always be tensions between these components of common good. This is why it should be accompanied by some “process concepts”, namely, deliberations and compromises or pragmatic consensus between all the actors involved (Stanton-Jean 2011). The practice of pragmatism is a useful tool to allow deliberations, participation, and consultations to reach a compromise that will permit one to preserve the freedom of expression and to respect the diversity of religious beliefs (Hottois 2004, p. 38).

The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, being the outcome of a large consultation process, offers an effort to apply such an approach in many of its articles. Its principles on Social Responsibility and Health and on Interrelation and complementarity of the principles are good examples. Article 14, Social responsibility and health states that access to health and social development is a fundamental right of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic, or social condition. It also proposes that progress in science and technology should contribute to this access because health is a social human good. This access includes inter alia reduction of poverty, access to nutrition and water, improvement of living conditions and the environment, elimination of the marginalization, and the exclusion of persons on the basis of any ground. Article 26 explains clearly that the principles stated in the declaration are complementary and interrelated and to be considered in the context of the other principles as appropriate and relevant in the circumstances (UNESCO 2005).

Although the Declaration is called “Universal,” it carries the features necessary to use it when we talk about Global common good or Global Health. It does not propose universal norms but a set of principles that can be contextualized depending on the culture of different nations or groups.

A school of thought is strongly opposed to that perspective and affirms that such a position is working from a neocolonial approach and that individual rights should prevail. They, most of the time, adopt a public good approach that tends, for example to see health care as a commodity and promote a market-driven approach. Health from a public good viewpoint becomes merchandise and is therefore accessible only to those who are able to pay to benefit from all the scientific advances.

Objections are also coming from those who argue that it would be impossible to have common decisions about how to allocate resources for example in education and health, or how to prevent people from benefitting without contributing and become free riders. Another major issue is related to individualism that is so entrenched in western societies where people cannot accept restrictions to their individual choices by public health regulations like the ones on tobacco, that restrict the right to smoke in public places.

But this neoliberal and neocolonialist perspective is being contested more and more. Indeed the aging of the population, the development in genomics and genetics, the often mismanagement of clinical trials in developing countries, the organ trafficking, the lack of benefit sharing with low-and middle-income countries (LMIC) has promoted new thinking in the bioethics community that for sure will continue to be challenged.

Examples Of Ethical Issues

A major feature of a global common good approach is the fact that it is based on a contextualized perspective. Circumstances and context, either it be economic, cultural, or social influence the moral decision. “What is different in the emerging bioethics of the common good is that reasoning, judgments and virtues are now more clearly understood to have a social dimension, and to be embodied in and through structures, institutions, and on ongoing practices, not only in the “choices” of individual agents” (Cahill 2004, p. 65).

Cahill gives the example of a contextualized decision based on the common good. A father with AIDS in Zambia, Africa, who has to decide if he or his daughter, also with AIDS, will benefit from the one AIDS treatment that he can afford. He decides to let his daughter die knowing that if he died, there will be nobody to care about his family.

In developed countries, we now also have to come to terms with limitations. In a publicly funded healthcare system, some very expensive treatments could be avoided to protect the system and keep it available to all based on a common good approach. Recently a woman in Canada refused to be voluntarily dialyzed so as to live a couple of months more. She said: “I am 89 years old. I have had a good life and do not want the system to spend more money on me.” We could also mention all the expensive diagnostics that are paid for by rich people for their genome sequence so that they may benefit from personalized medicine.

The Ebola outbreak in 2014 is also an interesting example of how the lack of a common good approach has contributed to the weakness of the health care and public health education system in affected countries. A vaccine would probably have been developed now if this outbreak had happened in developed countries where modern health care and research facilities exist. This disaster has been qualified by John Ashton, president of the UK Faculty of Public Health as “the moral bankruptcy of capitalism acting in the absence of an ethical and social framework” (as cited in Lancet 2014, p. 637). This is showing an absence of responsibility, global justice, and solidarity.

Conclusion

Globalization is here to stay and will continue to raise questions about what is acceptable in the field of life and social sciences and about what kind of decision-making process can help all the nations to agree on a set of values and principles that could be shared and used in a flexible and contextualized manner so as to permit cultural, social, economic, and legal diversity to be taken into consideration. A common good perspective based on responsibility, solidarity, justice, and autonomy is one of the options. But more discussions, debates, and deliberations need to continue between bioethicists, scientists, health professionals, government officials, research sponsors, and citizens from all over the world to find a way to live together and allow all the regions to benefit from the advancements of science and technology.

Bibliography :

- Baldacchino, J. (2002). Ethics and the common good: Abstract vs. experiential. Humanitas, XV(2), 25–59.

- Cahill, L. S. (2004). Bioethics and the common good (p. 65). Milwaukee: Marquette University Press.

- Engelhardt, H. T., Jr. (1996). The foundations of bioethics (p. 11). New York: Oxford University Press. First edition 1986.

- Gracia, D. (2014). History of global bioethics. In H. A. M. J. ten Have & B. Gordijn (Eds.), Handbook of global bioethics (p. 27). Dodrecht: Springer.

- Graziaux, E., & Lemoine, L. (2006) Avant-propos, [Foreword] dans Pierre Boitte, Bien commun et système de santé [Common good and health systems] (p. 5). Paris: Cerf.

- Hottois, G. (2004). Qu’est-ce que la Bioethique? [What is bioethics?] (p. 38). Paris: Vrin.

- Jobin, G. (1998). Le bien commun à l’épreuve de la pensée éthique contemporaine [Common good in the context of contemporary ethical thinking]. Revue d’Éthique et de théologie morale, Le Supplément, (204), 131.

- (2014). Ebola: a failure of collective international action. Editorial, 384, 637.

- Mappa, S. (1997). Essai historique sur l’intérêt général:Europe, Islam, Afrique coloniale [Historical essay on general interest: Europe, Islam, colonial Africa] (p. 12). Paris: Karthala.

- Stanton-Jean, M. (2011). La Déclaration universelle sur la bioéthique et les droits de l’homme: Une vision du bien commun dans un contexte mondial de pluralité et de diversité culturelle? Ph.D. thesis, Faculty of Arts and Sciences (Bioethics option), Montreal, University. Retrieved October 5, 2014, from https://papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1866/5181/StantonJean_Michele_2011_these.pdf;jsessionid=9D10AB34D B1DC3FFD22189F414BC91FE

- (2000). Director general advocates access for all to “common good”, Paris, October 9. Retrieved August 30, 2014, from http://mailman.apnic.net/ mailing-lists/s-asia-it/archive/2000/10/msg00007.html UNESCO. (2005). Retrieved September 05, 2014, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001428/142825e.pdf#page=80

- Velasquez, M., Andre, C., Shanks, T., & Meyer, M.J. (1992). The common good. Issues in Ethics, 5(1). Retrieved August 30, 2014, from http://www.scu.edu/ethics/practicing/decision/common good.html

- Callahan, D. (1990). What kind of life: The limits of medical progress. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Flanagan, P. (2008). Calling the sleeper to wake: An ethic of the common good for information technology (Vol. 1). Ph.D. dissertation, Loyola University, Chicago. Retrieved August 20, 2014, from http://books. google.ca/books?id=YPZvjyh4pz8C&printsec=front cover&hl=fr#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Jonas, H. (1984). The imperative of responsibility. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.