This sample Development And Bioethics Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

What is the relation between development and bioethics? The conception of development used to address this question is the capabilities approach promoted in the UNDP reports on human development. Since the first report in 1999, this approach has undergone continuous revisions and refinements, but the main structure and core elements of the original concept have been preserved. Its theoretical underpinnings are presented, with emphasis on the contributions of Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum. In addition, the relation between human development, human rights, and bioethics is discussed. This is followed by an analysis of how this approach can be made use of in bioethics. It is argued that it can be of help in providing a more context-sensitive and thereby richer and thicker description and analysis of current bioethics challenges as well as in articulating a global agenda for bioethics. Finally, it is argued that if the ambition is bioethics with global aspirations committed to life (bioi) in general, then there is a need to broaden the capabilities approach so as to make the life conditions and potentials of other living beings as well a matter of concern for development.

Introduction

Development can be defined as a process in which someone or something grows or changes and becomes more advanced. Here development will be defined as how and in what ways people’s choices might be enlarged. In the first report on human development of the United Nations Development Programme, this emphasis on people is formulated thus “.. .people must be at the centre of all development” (UNDP 1990, Foreword, p. iii). The basic normative value underlying this approach is human freedom. That is, for development to be in compliance with the deepest longings and aspirations of every human being on this planet, it must aim at enlarging each individual’s possibility to choose in her own way what to be and what to do with her life.

In the report, a normative distinction is made between essential and additional choices. Among the first counts three: to lead a long and healthy life, to acquire knowledge, and to have access to resources needed for a decent standard of living (UNDP 1990, p. 10). To these choices are added six additional choices, ranging from [4] “political, [5] economic and [6] social freedom to [7] opportunities for being creative and productive, [8] enjoying personal self-respect and [9] guaranteed human rights” (UNDP 1990, p. 10). A second distinction introduced is between the formation of capabilities and the use people make of their acquired capabilities. Thirdly, human development thus conceived focus both on the process of expanding people’s choices as well as on the level of functioning achieved. As acknowledged in the report, this way of understanding human development represents one option among several alternative approaches that could have been made use of, such as the economic growth approach, the human capital formation approach, the human resource development approach, and the human welfare or basic human needs approach. The merit of the capabilities approach compared to these alternatives, say the authors, is that it:

- Looks at both the production and the distribution of commodities

- Targets not only the expansion of human capabilities but also their use

- Focuses on people’s choices regarding their life plans and livelihood

- Understands human development as a participatory and dynamic process

- Applies equally to less developed and highly developed countries (UNDP 1990, p. 11)

In the report, no content-full definition of the concept of capability is provided. In the 1997 report, however, the following tentative definition is introduced (UNDP 1997, p. 16):

In the capability concept the focus is on the functioning’s that a person can or cannot achieve, given the opportunities she has. Functioning refers to the various valuable things a person can do or be, such as living long, being healthy, being well nourished, mixing well with others in the community and so on.

In the 2000 report, the relation between functionings, capabilities, freedom, and human development is highlighted (UNDP 2000, p. 17):

The functionings of a person refer to the valuable things that the person can do or be. The capability of a person stands for the different combinations of functionings the person can achieve. Capabilities thus reflect the freedom to achieve functionings. In that sense, human development is freedom.

The conception of human development introduced in the first UNDP report has throughout the last 25 years undergone continuous revisions and refinements so as to accommodate better with the dimensions of human development particularly addressed in each annual report as well as with the challenges pertaining to measuring human development. The main structure and core elements of the original concept have, however, been preserved in the reports since published.

So far the epistemological and normative potentials of the capabilities approach have not been addressed within the context of bioethics (three exceptions are London 2005, Vidal 2010, and Solbakk and Vidal 2014). In what follows, the human development approach here introduced and its most relevant revisions will be addressed, with a view to how this approach can be made use of to provide a more context-sensitive and thereby richer and thicker description and analysis of current bioethics challenges. Thereby it will also become clear that the human development approach points toward the need of broadening the agenda of bioethics so as to include a whole range of background factors that affect the lives of millions of people such as poverty, hunger, social and political exclusion, gender disparity, environmental impoverishment, climate change, and social unrest and war.

In addition, the focus will be on how this approach can be of help in articulating a global agenda for bioethics. During the last 15 years, there has been a growing awareness of the need for articulating such an agenda, not the least because of the phenomenon of globalization.

Before discussing in more detail how the capabilities approach to human development can be applied within the context of bioethics, a closer look at its theoretical underpinnings seems warranted.

The Theoretical Foundations Of The Human Development Approach

The philosophical origin of human development conceived of as expansion of capabilities can be traced back to Amartya Sen’s seminal work in the 1980s of developing a sustainable methodological framework for measuring people’s life quality and making life quality comparisons between different people, societies, and nations possible. Another very influential scholar in this field is Martha Nussbaum. She has moved beyond Sen, in the sense that her approach is suggested as the basis for constructing a normative theory of social justice (Nussbaum 2011, p. 19). This is of particular relevance for bioethics for at least two reasons. First, she refers to an idea of human dignity as a starting point for her approach. This is an idea with broad cross-cultural resonance and great intuitive power that turns it into a universal principle (Nussbaum 2011, pp. 17–45, 69–100). This is a view also reflected in the first article on principles in the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. In this article, a link between human dignity and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms is established, and it emphasizes also the priority of the individual over the sole interest of science or society (UNESCO 2005, Article 3). Second, since Nussbaum is concerned not only with human capabilities but also with the capabilities of nonhuman animals (Nussbaum 2011, p. 18), her conception of development moves beyond the human sphere to include quality of life considerations of other sentient beings as well. In the last part of this essay, the bioethical implications of adopting Nussbaum’s expanded notion of development will be briefly addressed.

Both Sen and Nussbaum emphasize that capabilities do not just refer to a person’s inner potentials or abilities; they represent the different combinations of functioning a person can achieve given her potentials and the political, social, and economic environment in which she lives. Thus, a person’s realization of her capabilities depends on both inner and external factors and on both innate and formed abilities as well as on external factors (economic, political, and social factors) that might enable her to – or hamper her from – freely giving expression to her abilities. Nussbaum’s differentiation between basic, inner, and combined capabilities can be of help to clarify this point. First, inner capabilities are different from basic capabilities – i.e., innate faculties, powers, and potentials – in the sense that they refer to abilities that have been trained or developed as a result of interaction with the external environment in which a person lives. Second, the concept of combined capabilities refers to the opportunity of people functioning in accordance with their inner capabilities, i.e., “internal capabilities plus the social/political/economic conditions in which functioning actually can be chosen” (Nussbaum 2011, p. 22). Nussbaum warns against a meritocratic attitude to innate abilities and basic capabilities and states that to treat all people with equal respect implies to prioritize those in need of more help to get above a certain threshold of combined capabilities (Nussbaum 2011, p. 24). She uses the case of people with cognitive disabilities to highlight this point: the goal should be that they are assisted to such an extent that they can enjoy the same capabilities as so-called “normal” people, even when some of the opportunities can only be exercised through a surrogate (Nussbaum 2011, p. 24).

The normative distinction between capabilities and functionings has important policy implications, in the sense that a policy targeting functionings could be at odds with people’s possibility to exercise their freedom, while making capabilities the goals of policy would imply the opposite, i.e., of expanding people’s opportunity to choose for themselves what to be and do (Nussbaum 2011, pp. 25–26).

This finally brings up the question which capabilities matter most. On this point, Sen’s and Nussbaum’s projects deviate clearly from each other. Sen sticks to the original informational perspective of the approach, i.e., of highlighting the relevance of this approach as a pragmatic and result-oriented framework for measuring people’s life quality and assessing differences in real opportunities. He does not suggest which capabilities matter most for human development and freedom or stipulates a particular social policy for promoting human development (Sen 2004, pp. 77–80). Sen admits, however, that his approach is not value-free, since it “does point to the central relevance of inequality of capabilities in the assessment of social disparities” (Sen 2009, pp. 231–235).

Nussbaum agrees with Sen that when focusing on capabilities for the purpose of framing comparisons, it is not necessary to prescribe in advance which capabilities matter most, since all sorts of comparisons with regard to capabilities might be of relevance. On the other hand, if capabilities are understood as the foundation of basic political principles, are to be constitutional guarantees, and become the basis for a public policy promoting social justice, then one cannot avoid to address the normative question on which capabilities matter most (Nussbaum 2011, p. 29).

In the attempt at identifying those capabilities, Nussbaum, again, refers to dignity as the normative point of departure and asks: what living conditions make it possible for people to live lives worthy of the dignity they possess, and what living conditions deliver to other sentient beings lives worthy of their dignity (Nussbaum 2011, pp. 29–30)? She admits the vagueness of the idea of dignity but insists that focusing on dignity makes a difference compared, for example, to satisfaction, notably for three reasons. First, dignity relates to respect, a link also highlighted in Article 3 of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. Second, dignity is closely linked to the idea of active striving and thereby to the notion of basic capabilities (Nussbaum 2011, p. 31). And third, while people’s innate faculties, powers, and potentials might differ, dignity is equal in all human beings deemed with agency. Equipped with this understanding of dignity, her project of identifying what constitutes the most central capabilities can thus be formulated: what areas of freedom are so central that their removal would not make a life worthy of human dignity possible? Her answer is a list of ten central capabilities in which realization beyond a certain minimum is required to be able to live a dignified life.

The list of central capabilities here presented is normatively charged in several ways. First, individual persons are the primary owners of capabilities. Consequently, the formation and expansion of capabilities for the individual person should not be sacrificed for the sake of producing capabilities in a larger group. Capabilities belong “only derivatively to groups” (Nussbaum 2011, p. 35). This view echoes the priority of the individual stated in Article 3 on human dignity in the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. Second, each of these capabilities has to be secured; none of them can be subsumed under one of the others because of their “irreducible heterogeneity.” Third, two of the capabilities in the list, i.e., practical reason and affiliation, play a distinct role in organizing human development: promoting capabilities without respecting the individual’s practical reason violates her freedom to choose for herself what to be and what to do, and the reference to affiliation underlines the fact that expansion of capabilities cannot take place in a social and relational vacuum. Thus, these two capabilities “pervade the other eight, in the sense that when the others are present in a form commensurate with human dignity, they are woven into them” (Nussbaum 2011, p. 39). Fourth, this version of the capabilities approach does not represent a full-fledged theory of social justice; i.e., it does not say anything about how to solve inequalities of capabilities above a certain threshold. But seeking ways of expanding these ten capabilities to all citizens up to the level of a decent minimum represents a necessary condition for social justice. Finally, the question of what represents a justifiable threshold to aim for is only hinted at: each nation should strive to select a level that is aspirational without being utopian (Nussbaum 2011, pp. 40–42).

Human Development, Human Rights, And Bioethics

The 2000 UNDP report is of particular relevance to bioethics since here the relation between human development and human rights is explicitly addressed. Says the report:

Human rights and human development are both about securing basic freedoms. Human rights express the bold idea that all people have claims to social arrangements that protect them from the worst abuses and deprivations – and that secure the freedom for a life of dignity.

Human development, in turn, is a process of enhancing human capabilities – to expand choices and opportunities so that each person can lead a life of respect and value. When human development and human rights advance together, they reinforce one another – expanding people’s capabilities and protecting their rights and fundamental freedoms. (UNDP 2000, p. 2)

While the focus on rights directs the attention to the most vulnerable individuals and groups, especially to victims of exploitation, social exclusion, and discrimination, the human development approach conceives of the fulfillment of rights as a long-term dynamic process of expanding people’s choices. Consequently, the focus of attention is on the socioeconomic context within which realization or deprivation of people’s capabilities and rights might materialize. In the report, seven key features are highlighted that indicate the fruitfulness of combining these two perspectives.

The emphasis in this report on the social dimensions necessary to observe to promote human development and secure human rights and fundamental freedom, including non-discrimination, the focus on vulnerable groups and disadvantaged people, and the emphasis on global justice and on the need for stronger international action to remediate global inequalities are echoed in the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. This declaration was unanimously adopted by the member states of UNESCO in 2005. The family resemblance between the 2000 UNDP report and the UNESCO declaration on bioethics with regard to the centrality of human rights is rooted in a shared vision that only when human rights and fundamental freedom are respected can genuine advancement in human development and bioethics take place. In the next paragraph, the implications for bioethics of applying the integrated approach of human development and human rights will be addressed.

Current Challenges In Bioethics: The Integrated Approach Applied

Two cases will be used to illustrate the fruitfulness of addressing current challenges in bioethics from this double vantage point: ethical issues pertaining to adolescent pregnancy and abortion and the debate about exploitation in international clinical research conducted in poor and low-income countries.

Case 1: Adolescent Pregnancy And Abortion

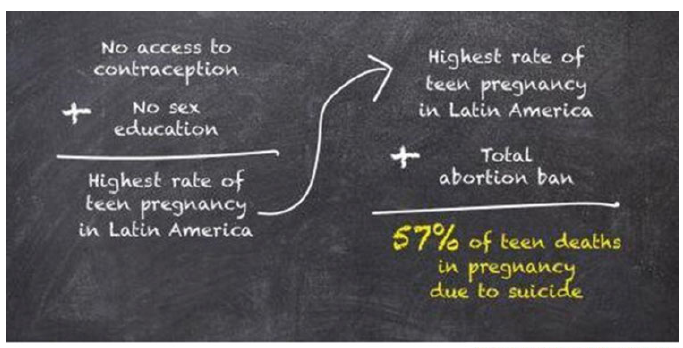

On November 13, 2013, the Thomson Reuters Foundation published a news article claiming that El Salvador’s total ban on abortion drives teenagers to commit suicide.

Another news story recently published provides a similar narrative from Ecuador.

Some of the same trends narrated in these news stories are reported in the first cross-national comparisons study on adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates recently published (Sedgh et al. 2015). The study reviews data from 49 countries in Asia, Europe, and sub-Saharan Africa – as well as the USA and Mexico. It was found that although adolescent pregnancy rates have declined since the mid-1990s in most developed countries, the rate remains exceptionally high in the USA. In four countries in sub-Saharan Africa, in some former Soviet countries, and in Mexico, the pregnancy rates were even higher. The authors emphasize the descriptive nature of the study, and they abstain from suggesting hypotheses that might help to explain the differences across countries or trends over time. They point, however, to a whole range of determinants that are of relevance when applying the integrated approach of capabilities and human rights to address this issue. The immediate determinants, say the authors, are two: sexual activity and contraceptive nonuse. The main difference across industrialized countries with regard to these two determinants is differences in “contraceptive prevalence” (Sedgh et al. 2015, p. 228). In addition come distal determinants related to social, economic, and cultural factors. Evidence from several studies in the USA and UK, referred to by the authors, indicate that the teen pregnancy rates are higher in the most socioeconomically disadvantaged groups: in the USA, the difference in rate between black and white teenagers is 100 versus 38, while qualitative studies from the UK associate high pregnancy rates among teenagers to existential and socioeconomic factors such as “unhappiness at home or at school and low expectations for the future” as well as “poor material circumstances” (Sedgh et al. 2015, p. 228). Two other findings in this study of particular relevance are that in the five countries with restrictive laws on abortion, i.e., Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, and Mexico, the estimated adolescent pregnancy rates were far higher than in any other country included in the study and, second, with the exception of Ethiopia, the estimated abortion rates were also higher in these countries. While the authors link the first difference to norms allowing for early marriage in these countries, they abstain from commenting on the second difference.

Figure 1. Adolescent pregnancies in El Salvador

Figure 1. Adolescent pregnancies in El Salvador

When viewing these narratives and figures from the vantage point of capabilities and human rights, it becomes evident that it is impossible to limit the ethical analysis of this issue to a discussion of the moral status of the fetus, the sanctity of human life, or the illegality of abortion. That is, one can simply not turn a blind eye to realities under which many of these teenagers live that seriously hamper their freedom to choose for themselves what to be and what to do and thereby live a life worthy of dignity. The ten capabilities proposed by Nussbaum could here be applied as a heuristic checklist to identify different forms of capability deprivation and the level of deprivation pregnant teenagers in different regions of the world and in different countries are prone to and suggest social policies to remediate these deficiencies that are within the range of possibility of each country to implement. As emphasized by Nussbaum, such policies should target capabilities, not functionings. Consequently, facilitating access to contraception and safe reproductive health services would not be sufficient to expand these girls’ opportunities to choose for themselves how to live their lives. What would be needed are social policies aimed at remediating those forms of capability deprivation that are the underlying causes of high pregnancy and abortion rates among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups of female teenagers. And analysing this situation from the vantage point of human rights would be of help in identifying the kind of institutions and social arrangements which existence and functioning these groups of vulnerable girls have a claim on, to protect them from sexual abuse, social exclusion and deprivation, and the risk of early deaths due to clandestine abortions – and secure them the freedom required to be able to live a dignified life.

Case 2: Exploitation In International Clinical Research

The phenomenon of exploitation in international clinical research conducted in resource-poor settings has for years been a topic of heated discussion and controversy in bioethics. One approach that has been very influential in the debate is the so-called fair benefit approach advocated by a group of libertarian bioethicists and philosophers in the USA. The theoretical justification underlying this position has been developed by Alan Wertheimer (Wertheimer 2008, pp. 63–104). He argues that any form of research on or with human research subjects involves a transaction in which two aspects should be taken into account:

- The participants’ voluntary nature, especially of the most vulnerable part of the transaction

- The way in which the “benefits” are distributed between the two parties interacting

The normative assertion, on which the fair benefit approach is based, is the distinction between “harmful exploitation” and “mutually advantageous exploitation”:

By mutually advantageous exploitation, I refer to those cases in which both parties (the alleged exploiter and the alleged exploited) reasonably expect to gain from the transaction as contrasted with the pretransaction status quo…. I shall generally presume that mutually advantageous transactions are also consensual. (Wertheimer 2008, pp. 67–68)

According to this view, oppression, attack, deception, betrayal, coercion, or discrimination may be harmful to people, but it is not exploitation. Exploitation occurs first when B receives an unfair level of benefits as a consequence of the interaction between A and B. Fairness is related to the burden to be borne by B and the amount of benefits to be received by A. Thus, as long as the transaction takes place between two consenting parties and it is mutually advantageous, it is neither harmful nor unfair. In a paper published in JAMA in 2013 and criticizing the last revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, the protagonists of the fair benefit approach reaffirm their position on exploitation and thus (Millum et al. 2013, p. 2144):

When research does not prove an intervention effective phase 1 and 2, and negative phase 3 research trials participants from poor countries with limited access to medical services are unlikely to benefit at all from these requirements. In these cases, a research project might supply clean water, new clinics, or build local medical and research capacity. If this level of benefits is fair, then the research will not be exploitative.

Addressing the issue of exploitation in international clinical research from the vantage point of capabilities and human rights implies a completely different framing of the situation. To use Alex London’s wording, in order to avoid falling into moral minimalism, it is necessary to take into account the economic, social, and political reality of the individuals involved in research and take these realities as the starting point to devise the conditions and requirements of any model deemed as “fair” (London 2005). This does not only relate to local conditions of fairness but also to global conditions that may put (or have put) such individuals and communities at a disadvantage and lead (or have led) them into their current situation of vulnerability and deprivation of capabilities. The minimalist picture painted by the advocates of the fair benefit approach thus misrepresents the situation at a crucial point, since assessment of whether an interaction is exploitative or fair cannot be done on the basis that the injust conditions under which impoverished communities and vulnerable individuals live are facts of the world that fall outside the scope of normative consideration.

The alternative way of addressing the phenomenon of exploitation in international clinical research here suggested implies taking into account the conditions of vulnerability, including the trigger factors, the human needs of the individuals and communities implicated, the opportunities that they have had and they currently have to make decisions and claim their rights, the scope of real options available to them, and finally, the opportunities that the individuals have to expand their capabilities. This provides the possibility of a more context-sensitive and thereby richer and thicker description of the phenomenon of exploitation than that offered by the fair benefit approach. Second, it calls for the need of grounding the duties in international clinical research within a broader normative framework of social, distributive, and rectificatory justice. Third, it favors policies that focus the attention on expanding peoples’ capabilities and freedom to choose for themselves. Consequently, the suggestion of Millum, Wendler, and Emanuel of establishing a situation of fairness by supplying things, such as clean water, new clinics, or building local medical and research capacity, would hardly comply with the normative requirements of the human development approach, since this would imply forcing poor communities and impoverished populations to enter into negotiations about benefits in situations of enormous inequality of bargaining power. Instead of resolving the problem of exploitation, this could pave the way for a double form of exploitation: first, on the level of interaction between science and community leaders and, second, on the level of interaction between community leaders and groups of ailing patients in the same communities “encouraged” by the community leaders to enroll in the hosted studies for societal reasons. To recall Nussbaum’s assertion on the formation and expansion of capabilities, the freedom of the individual person to choose for herself should not be sacrificed for the sake of producing capabilities in a larger group. Capabilities belong “only derivatively to groups” (Nussbaum 2011, p. 35). Finally, this approach would imply focusing the attention on what kind of institutions and social arrangements have to be put in place to protect fundamental human rights and remediate the situation of gross background injustice and deprivation of capabilities that existed before the research was undertaken.

Development And Bioethics In The Face Of Globalization

The question that will be addressed in this last paragraph is how can the human development approach be of help in articulating a global agenda for bioethics? This will be done by addressing some of the core observations and suggestions made in the 1999 UNDP report on globalization with a human face in light of the articles in the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights (UDBHR) that deal with transnational and global issues. Reference will also be made to later UNDP reports and development goals of particular relevance for articulating a global agenda for bioethics. The aim of this reading exercise is to identify white spots in the UDBHR concerning bioethical issues of global relevance and thereby contribute to a more extended and richer articulation of such an agenda.

Although globalization is not a new phenomenon, it has, as acknowledged in the 1999 report, some characteristics that in a radical way have made the world become smaller and linked people’s lives in ways that have increased dramatically the potential of causing “.. .extraordinary harm as well as good” (UNDP 1999, p. 1). In the report, four features defining the current era of globalization are highlighted.

The first challenge identified in the 1999 UNDP report is the need for stronger governance to ensure a form of globalization that has expansion of people’s capabilities and reduction of human rights violations – not profit maximization – as its primary goal. This calls for strategies that reduce poverty and vulnerability, lead to less marginalization of people and countries and less instability of societies, decrease disparity within and between nations, and generate less environmental destruction (UNDP 1999, p. 2). Article 8 of the UDBHR on respect for human vulnerability and personal integrity emphasizes the importance of protecting individuals and groups of special vulnerability. And Article 14 on social responsibility and health calls for the need of reducing poverty and for eliminating marginalization, but the focus of attention in these articles is people, not countries as well, as is the case in the UNDP report.

The second challenge is the need for a fairer and wider sharing of the opportunities and benefits of globalization (UNDP 1999, pp. 2–3). This concern is not directly reflected in Article 10 of the UDBHR on equality, justice, and equity, but in Article 15 on sharing of benefits, emphasis is put on the duty to share the benefits resulting from any scientific research and its applications widely, in particular with developing countries.

The third challenge concerns the new threats to human security following in the wake of globalization. In the report, seven such threats are listed: (1) economic insecurity caused by the instability of global financial markets (2) job and income insecurity generated by economic and corporate restructuring, dismantling of institutions of social protection, and global competition (3) health insecurity – the risk of spread of infectious diseases increases with more traveling and migration (4) cultural insecurity – an unbalanced flow of culture from rich countries to poor countries put cultural diversity and identity at risk (5) personal insecurity – globalization increases the possibility of illicit trade and trafficking in drugs, women, weapons, and laundered money (6) environmental insecurity – environmental degradation and destruction threatens people worldwide but the poor are worst affected (7) political and community insecurity – rise of social tension threatens political stability and community cohesion (UNDP 1999, pp. 3–5). Article 12 of the UDBHR addresses the issue of respect for cultural diversity and pluralism, but the scope does not extend to include the risk of loss of cultural diversity that might follow from the cultural dominance of rich countries. And in Article 21 on transnational practices, the challenges pertaining to illicit trafficking of organs, tissues, samples, genetic resources, and genetic-related materials are reflected. The article also mentions the danger of bioterrorism, but it is mute with regard to the other forms of illicit trafficking mentioned in the UNDP report, such as drugs, women, and weapons. Furthermore, Article 16 on protecting future generations and Article 17 on protection of the environment, the biosphere, and biodiversity reflect the challenges that environmental degradation and destruction represent for human life and other life forms on this planet. The impact of climate change on human development and future generations is, however, not reflected in these articles nor in the 1999 UNDP report. The enormous importance of this issue for human development and a viable future on this planet is, however, acknowledged and a subject of extensive treatment in the 2007/2008 UNDP report. The way these challenges are articulated in this report makes it also painstakingly clear why climate change needs to be acknowledged and articulated as a core concern for a bioethics with global aspirations.

The fourth challenge relates to the role of new information and communication technologies as drivers in the globalization process but also as dividers of the world into the connected and the isolated and excluded. These challenges are only indirectly reflected in Article 15 of the UDBHR on sharing of benefits, through the obligation expressed that benefits resulting from any scientific research and its applications should in particular be shared with developing countries.

The fifth challenge is of particular relevance for a global agenda of bioethics since it deals with the human development potential that might follow from global technological breakthroughs but also how liberalization, privatization, and tighter intellectual property rights pertaining to such breakthroughs might lead to new forms of marginalization and exclusion of poor people and poor countries. The effects of the TRIPS regime (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) of the World Trade Organization can serve to illustrate this challenge. Although this regime is claimed to be the most efficient and cost-effective way of promoting medical innovations, it is for several reasons “morally deeply problematic” to use Thomas Pogge’s wording (Pogge 2007). In order to give weight to his argument, Pogge invites the reader to participate in a tentative assessment of the effect of this regime on the four main affected groups, i.e., (1) the pharmaceutical industry and their researchers and shareholders, (2) actual and future patients in the affluent part of the world, (3) generic manufacturers of medicines, and (4) actual and future patients in poor and low-income countries (p. 9). The results of his assessment are hardly surprising. The first group of stakeholders benefit grossly from the global enforcement of this regime, while the effect on the second group, i.e., actual and future patients in the affluent part of the world, is less clear cut. For the third group of stakeholders, on the other hand, this regime represents a substantial infringement upon their possibilities of producing cheaper versions of patented drugs, something which in its turn reduces the access possibility of cost-saving-oriented patients in the affluent part of the world as well of patients in poor and low-income countries to cheaper and/or affordable medicines. Finally, for the group of stakeholders most in need, the TRIPS regime is undoubtedly “socially harmful” in a dramatic way, since millions die because of the restrictions this regime puts on the production and thereby also on the accessibility of generic drugs (Pogge 2007, pp. 97–108). This regime represents an initiative from democratic governments in the affluent parts of the world which was enforced upon the global community in ways that do not comply with the principles of transparency and dominance-free dialogue or to formulate this statement from the vantage point of the narrative of the Tower of Babel: the language of the TRIPS regime is not a genuinely universal normative framework that makes everyone an inhabitant of the global city; on the contrary, its effect is that large numbers of the poorest communities and peoples in the world fall apart and outside the possibility of accessing the fruits of medical innovations. The language of equitable access to new emerging technologies must, in order to become not just rhetorical wordplay, be able to overcome the different barriers that hinder equitable access to new emerging technologies. Among these are financial barriers, scientific illiteracy, geographical barriers, language and cultural barriers, discrimination, racism, gender bias, social exclusion, and unrest. In addition, social determinants of health have to be observed to make such a language function in an unjust world. Among these determinants count income and social status, education, physical environment, employment and working conditions, social support networks, genetics, personal behavior and coping skills, and health services – access and use. In other words, if justice requires providing equitable access to the benefits of scientific and technological breakthroughs, then these barriers and determinants must be addressed as a matter of global justice.

The sixth challenge identified in the 1999 UNDP report relates to what the report labels the “invisible heart of human development,” i.e., care (UNDP 1999, p. 7):

Caring labour providing for children, the sick and the elderly, as well as all the rest of us, exhausted from the demands of daily life is an important input for the development of human capabilities. It is also a capability in itself.

…

But today’s competitive global market is putting pressures on the time, resources, and incentives for the supply of caring labour. Women’s participation in the formal labour market is rising, yet they continue to carry the burden of care women’s hours spent in unpaid work remain high.

In the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, care is only referred to in terms of access to quality health care in Article 14 on social responsibility and health, notably with special emphasis put on such access to women and children, and in Article 15 on sharing of benefits. The gender imbalance with regard to care labor or other forms of gender disparity are not on the declaration’s agenda. It is due time that promoting gender equality and empowering of women is allocated space on this agenda and acknowledged as a central concern for global bioethics. In the forthcoming 2015 UNDP report, care work is reemphasized as critical for human development. The seventh and last challenge identified in the 1999 UNDP report is to reinvent national and global governance so as to install equity as the core value of local, national, regional, and global governance. To achieve this, say the authors of the report, three commitments must be at the forefront (UNDP 1999, pp. 7–9):

- First, a commitment to global ethics, justice, and respect for the human rights of all people

- Second, a commitment to human well-being as the end, with open markets and economic growth as means

- And third, commitment to respect for the diverse conditions and needs of each country

These are all commitments that need to be acknowledged and articulated as central commitments for a bioethics with global aspirations. But these core commitments are hardly sufficient if the ambition is to develop a global bioethics that is committed not only to the expansion of human capabilities and protection of human rights worldwide but to other forms of life on this planet as well, i.e., to bioi in general. This, however, is a commitment that falls outside the anthropocentric conception of development promoted in the UNDP reports. In the last chapter of Nussbaum’s book on the capabilities approach, the possibility of broadening the capabilities approach to include other living beings as well is briefly discussed. “Any approach based on the idea of promoting capabilities,” she says, “will need to make a fundamental decision: Whose capabilities count?” (Nussbaum 2011, p. 157). Nussbaum lists five possible answers to this question (Nussbaum 2011, pp. 157–158):

- Only human capabilities should count as ends in themselves; the capabilities of other living beings have only instrumental value.

- Human capabilities are the primary focus, but the capabilities of nonhuman creatures with whom human beings can enter into valuable relationships should also count.

- The capabilities of all sentient beings should count as ends in themselves.

- The capabilities of each living being, including plants, should count.

- The capabilities not of individual living beings but of living species and ecosystems should count.

If the ambition is to develop a bioethics that is truly global in its scope and biocentric with regard to its commitment to expanding capabilities and protecting rights, then the question posed by Nussbaum needs to be put on the agenda, and the bioethical implications of each possible answer needs to be fully articulated.

Conclusion

This essay has discussed the relation between development and bioethics. The conceptional point of departure for this discussion has been the approach made use of in the UNDP reports on human development, i.e., the capabilities approach of Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum’s further elaboration and suggestion of using it as the basis for constructing a normative theory of social justice. It has been argued that the combination of this approach with human rights makes it possible to provide a more context-sensitive and thereby richer and thicker description and analysis of current bioethics challenges. Two case examples have been used to demonstrate the fruitfulness of this approach: adolescent pregnancy and abortion and exploitation in international clinical research. In addition, it has been demonstrated how the integrated approach of capabilities and human rights might be of help in articulating a global agenda for bioethics. Finally, it has been argued that if the ambition is to develop a bioethics that is truly global in its scope and biocentric with regard to the commitment of expanding capabilities and protecting rights, then there is a need to move beyond the anthropocentric conception of capabilities promoted in the UNDP reports.

Bibliography :

- Culp-Ressler, T. (2014). El Salvador’s total abortion ban is driving pregnant teens to commit suicide. Thomson Reuters Foundation. Accessible at: http://thinkprogress. org/health/2014/11/13/3591855/el-salvador-abortion-sui cide/. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- Ecuador High Life. (2015). Doctors say that 70 percent of patients who have illegal abortions are teenagers. Accessible at: http://ecuador-highlife.com/doctorssay-that-70-percent-of-patients-admitted-to-mantahospitals-are-teenage-girls-who-have-had-illegal-abortions/. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- London, A. J. (2005). Justice and the human development. Approach to international research. Hastings Center Report, 35(1), 24–37.

- Millum, J., Wendler, D., & Emanuel, E. (2013). The 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Helsinki. Progress but many remaining challenges. JAMA, 310(20), 2143–2144.

- Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating capabilities. The human development approach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni- versity Press.

- Pogge, T. (2007). Intellectual property rights and access to essential medicines, policy innovations. http://www. policyinnovations.org/ideas/policy_library/data/FP4

- Sedgh, G., Finer, L. B., Bankole, A., et al. (2015). Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: Levels and recent trends. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 223–230.

- Sen, A. (2004). Capabilities, lists, and public reason: Continuing the conversation. Feminist Economics, 10(3), 77–80.

- Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Solbakk, J. H., & Vidal, S. M. (2014). Clinical research in resource-poor settings. In H. ten Have & B. Gordijn (Eds.), Handbook of global bioethics (pp. 527–550). New York: Springer.

- UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. (2005). Available at: http://portal.unesco.org/shs/en/ev.php-URL_ID=1883&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC& URL_SECTION=201.html. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- United Nations. (2015). The millennium development goals report. Accessible at: http://www.un.org/ millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2015.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (1990). Human development report. Available at: http://hdr. undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr1997/chapters/. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (1997). Human development report. Available at: http://hdr. undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr1997/chapters/. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (1999). Human development report. Available at: http://hdr. undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr1997/chapters/. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (2000). Human development report. Available at: http://hdr. undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr1997/chapters/. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (2007/ 2008). Human development report. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr1997/chapters/. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- Vidal, S. (2010). Bioética y desarrollo humano: una visión desde América Latina. Revista Redbioética/ UNESCO, No. 1. Accessible at: http://www.unesco. org.uy/shs/red-bioetica/es/revista/ano-1-no-1-2010/ sumario.html. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- Wertheimer, A. (2008). Exploitation on clinical research. In S. Hawkins & E. J. Emanuel (Eds.), Exploitation and developing countries. The ethics of clinical research (pp. 63–104). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Sen, A. (1979). Equality of what? Stanford University: Tanner lectures on human values. Accesible at: http:// tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/s/sen80.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2015.

- Sen, A. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Sen, A. (2010). The place of capabilities in a theory of justice. In H. Brighouse & I. Robeyns (Eds.), Measuring justice: Primary goods and capabilities (pp. 239–253). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.