This sample Fertility Control Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

The entry opens with an overview of the history and characteristics of modern fertility control methods and comparative information on their effectiveness in preventing unwanted pregnancies. A discussion of their geographic prevalence in a global perspective follows, including information on barriers to access to contraception, particularly for vulnerable groups. The ethical aspects of the fertility control debate are discussed, with an analysis of the natural law theory as interpreted by opponents of contraception, and the three main pro-contraception moral arguments: self-determination, women’s health, and children’s rights.

Introduction

The phrase “fertility control” refers to methods and devices used to prevent unwanted pregnancies, making intercourse without conception possible. The phrase has many synonyms: “birth control,” “planned parenthood,” and, in the case of couples that are in a stable relationship, “family planning.” Another synonym is “contraception,” a term coined in 1886, from the Latin contra-(against) and a shortened form of the word “conception.”

Historically, the use, advertising, and distribution of contraceptives have been ethically and socially controversial. Access to birth control, or to information on birth control, has been actively hindered by moral entrepreneurs and policymakers. It still is, in some parts of the world, for some types of contraceptives and for some groups. The use of, access to, and distribution of birth control methods and their regulation are, and have always been, a heavily politicized subject.

History And Development

Scientific knowledge of the mechanisms of human reproduction is a relatively recent acquisition. Scientists first identified sperm in the late seventeenth century and were able to understand its function only about a century later. Mammal eggs were not identified until the 1820s, and the timing of women’s ovulation was discovered in the 1930s. Nevertheless, our ancestors had understood the connection between penile-vaginal intercourse and conception. Abstinence, sex without intercourse (“outercourse”), penis withdrawal before or without ejaculation, fertility prediction, and extended breastfeeding have always been used as fertility control methods, also in societies where fertility control was prohibited or strongly discouraged by social, political, religious, and legal rules. There is also evidence that nonbehavioral contraception, including barrier methods and oral birth control, was practiced in ancient civilizations. However, it was not as reliable, safe, and noninterfering with sexual pleasure as the birth control methods available today (Knowles 2012).

Barrier Methods

Throughout recorded history, women all over the world – from Africa to China, from Japan to ancient Greece – have used various substances and devices to absorb seminal fluid (vaginal sponges), to kill semen (spermicide creams, foams, or jellies), or to prevent semen from accessing the uterus (female condoms, diaphragms, and cervical caps). It is a very old tradition. The Talmud makes reference to the use of vaginal sponges for contraception. In ancient Egypt, instructions for the preparation and use of mixtures thought to function as spermicides were buried with the dead to prevent unintended pregnancy in the afterlife. In the first century C. E., Pedanius Dioscorides, a Roman physician of Greek origin, wrote his treatise De Materia Medica, which remained an authoritative, comprehensive source of birth control information for many centuries (Knowles 2012).

Vaginal sponges, spermicides, diaphragms, and cervical caps, no longer made of natural materials, are still used today, but they are not a popular birth control method, notwithstanding the substantial improvements with regard to their availability, quality, reliability, and comfort of use (see sections “Effectiveness” and “Geographic Prevalence” below).

The most popular barrier method today is the male condom, which is of more recent introduction (see section “Geographic Prevalence” below). The earliest uncontested description of the use of penis coverings made of cloth, for protection against syphilis, appeared in the late sixteenth century in a treatise written by the anatomist Fallopius. The first record that such coverings were also used for purposes of birth control appeared 30 years later in a treatise written by the prominent Catholic theologian Lessius, who argued that the practice was immoral. The oldest condom was found in the foundations of Dudley Castle in England. It is made of animal gut and dates back to the mid-seventeenth century (Collier 2007).

In the Western world, the condom market grew steadily in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, notwithstanding legal restrictions to the manufacturing and advertising of contraceptives. The first condoms were made of natural materials and were used more than once. The first rubber condoms were produced after Goodyear patented the vulcanization of rubber in the mid-nineteenth century. These were as thick as a bicycle’s inner tube. In the 1920s, with the invention of latex, condoms quickly became the most commonly prescribed method of birth control in the USA. The 1930s saw the patenting of the first fully automated condom assembly line and the relaxation of legal restrictions on condom sale and advertisement in most Western countries, with notable exceptions including Ireland, where condoms were sold legally for the first time in 1978. Condom sales boomed after the war. In the 1950s, 42 % of all Americans of reproductive age and 60 % of British married couples relied on condoms for birth control (Collier 2007).

In the 1960s and 1970s, the use of condoms decreased, concomitantly with the introduction of the birth control pill and the intrauterine device (IUD) and the availability of effective treatment for previously incurable sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). The 1980s saw a major increase in condom use, when some governments and part of the media at last gave an adequate amount of attention to the HIV pandemic. Condoms began to be sold outside of pharmacies. Condom use has grown steadily over recent decades. This trend is expected to continue, especially in Asia and the Pacific (Collier 2007 and UNAIDS 2004).

The female condom, first introduced into the USA in the late 1990s and almost a decade later in Europe, never became a popular birth control method, despite also offering protection against STDs. For mechanical reasons, the female condom is less user-friendly than the male condom. The unwanted flow of semen into the vagina is more likely to occur (see section “Effectiveness” below).

The last type of barrier birth control method is the IUD. Devices to be inserted into the uterus and left in place to provide long-term contraceptive protection were invented in Germany in the early twentieth century. Made of silkworm gut, these worked as contraceptives, but led to infections of the uterus that were often lethal before penicillin became widely available in the 1940s (Knowles 2012).

Considerably safer versions of the IUD were successfully marketed from the 1960s onward. However, a defective type of IUD, marketed in the late 1970s when the US federal safety and quality regulations for such devices were still inadequate, caused severe infection and unwanted pregnancy, often resulting in late miscarriage. This gave the IUD a poor reputation, especially in the USA. Today’s IUDs are considerably safer and endorsed by the World Health Organization as among the safest, cheapest, and most effective birth control methods (Knowles 2012).

Hormonal Methods

We have copious evidence that the ingestion of fruits or herbs for the purposes of oral contraception is an ancient tradition. Treatises have been written on the subject, including the monumental study, Thesaurus Pauperum, written by Petrus Hispanus, believed by some historians to be the same man who became Pope John XXI in 1276. Petrus Hispanus researched and collected a multitude of herbal recipes that women had been using for birth control since antiquity across different continents. However, contraceptive knowledge started to vanish in Europe after the thirteenth century, along with the idea of oral birth control in conventional medicine (Knowles 2012).

The first birth control pill was developed in the 1940s and 1950s. The medical research and the very expensive clinical trials necessary were mainly funded by the American biologist and philanthropist Katharine Dexter McCormick (Knowles 2012). The first country to approve the birth control pill for marketing was the USA in 1960. Australia, the UK, and West Germany followed in 1961 and other Western European countries in the 1960s and 1970s.

There are other hormonal contraceptive methods that, unlike the pill, do not require daily action from the patient and are effective for weeks, months, or years once put in place. These include hormone injections and hormone-releasing patches or implants placed under the skin. There is also a recently introduced progestin-medicated IUD. Unlike traditional copper IUDs, medicated IUDs reduce rather than increase menstrual bleeding and possibly lead to the disappearance of menstrual periods altogether; they are indicated for women with excessive menstrual bleeding or blood clots.

Emergency Contraception (EC)

Contraception and abortion have been, and still are, often discussed jointly as they are historically, morally, and empirically interwoven. However, contraception, or birth control, is radically different from abortion; it prevents, rather than ends, pregnancy. While most contraceptives produce their effect if used before or during intercourse, a few birth control methods are effective if used after intercourse (emergency or “postcoital” contraception). This does not make them abortion methods, as biology shows that the onset of gestation does not coincide with intercourse. After intercourse, the sperm and the egg cell unite in one of the fallopian tubes. This process is known as fertilization. It is not contextual with intercourse. Sperm cells can survive for days waiting for one of the ovaries to release the egg cell (ovulation). The fertilized egg then begins its journey toward the uterus, arriving after up to 1 week, and it attaches to the uterine wall. This process is called implantation, and according to the most prominent international medical-professional societies, it marks the onset of human gestation (ACOG 1965).

Safe and effective emergency contraception (EC) is of very recent introduction. Poorly efficacious and often toxic herbal remedies have been used for many centuries to induce menstruation after intercourse, as reported by the eminent Greek physician Hippocrates and by Petrus Hispanus in his Thesaurus Pauperum. Another ineffective and dangerous EC method, advertised in some Western countries in the 1800s, is vaginal douching with aggressive detergents. This causes inflammation and infection while failing to prevent pregnancy (Knowles 2012).

Two safe and effective EC methods are currently marketed: the EC hormonal pill and the IUD.

In the early 1970s, the Canadian gynecologist Albert Yuzpe popularized the “Yuzpe EC method,” consisting of ingesting various birth control pills at the same time, after intercourse. This method induces menstruation within hours, and it has been used by millions of women. It was not until the late 1990s that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the marketing of America’s first dedicated EC pill. Various types of EC pills have been marketed worldwide since then (Knowles 2012).

The EC pill should not be confused with the abortion pill. The former is a contraceptive. It is effective if taken within a few hours to a few days after intercourse, depending on the type of pill. There is medical evidence that it works by preventing fertilization. If fertilization has already occurred, EC does not harm the developing embryo and the pregnancy progresses normally (Noé et al. 2010). The abortion pill is an abortifacient drug. It is a less invasive alternative to surgical abortion and is also marketed as such. It is effective if taken in the first trimester of gestation.

The IUD can also be used for safe and effective emergency contraception. Its insertion, a few hours after unprotected sex, prevents pregnancy.

Permanent Surgical Sterilization

It is controversial whether permanent sterilization can be considered a birth control method. Irreparable loss of the procreative capacity could be regarded as too great a side effect to be acceptable, as the person may change their mind about their reproductive plan. However, voluntary sterilization is widely practiced for birth control today, especially in Asia and on the American continent (see section “Geographic Prevalence” below). Today’s sterilization methods do not require major surgery and do not affect sexual functioning, nor do they interfere with sexual pleasure. Sterilization consists of severing and sealing surgically the small ducts that take the sperm from the testicles to the penis (vasectomy) or the tubes that connect the ovaries to the uterus (tubal ligation).

The first vasectomies and tubal ligations were performed, on medical grounds, in the late nineteenth century in Europe. For the first half of the twentieth century, vasectomy was typically nonconsensual and usually performed on imprisoned men or men who had been diagnosed with particular conditions, especially psychiatric illnesses and cognitive handicaps. After WWII, vasectomy and tubal ligation started to be used for voluntary birth control, initially with some restrictions depending on age and the number of living children. In the USA, vasectomy became popular in the 1970s. Until the mid-1970s, tubal ligation involved major abdominal surgery under general narcosis. After laparoscopy was introduced, the popularity of the procedure gradually increased. In the USA, it peaked in the 1990s and it is still relatively popular today, along with vasectomy (Knowles 2012).

Contraception Facts

Effectiveness

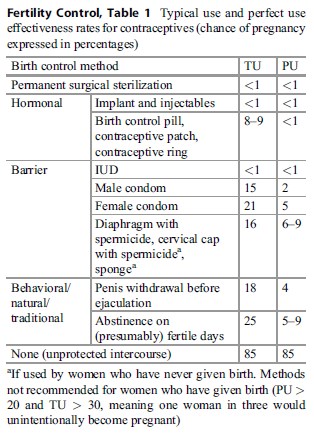

Some birth control methods are more effective than others. This is assessed in two ways. The perfect use (PU) effectiveness rate refers to the percentage of unwanted pregnancies, when the method is used properly and at every act of intercourse. The effectiveness rates for actual use, or typical use (TU), are of all users of that particular method, including incorrect or discontinuous use. Rates are generally presented for the first year of use.

Some methods are more user dependent than others. If the birth control method does not require frequent action from the user, there is hardly any discrepancy between PU and TU. Permanent sterilization, the IUD, the implant, and combined injectables have a PU and TU rate well below 1 %, meaning that less than 1 in 100 users will unintentionally become pregnant in the first year of use. For other methods, the PU-TU pregnancy rate gap is considerably bigger, as illustrated in Table 1 (Trussell 2007).

Geographic Prevalence

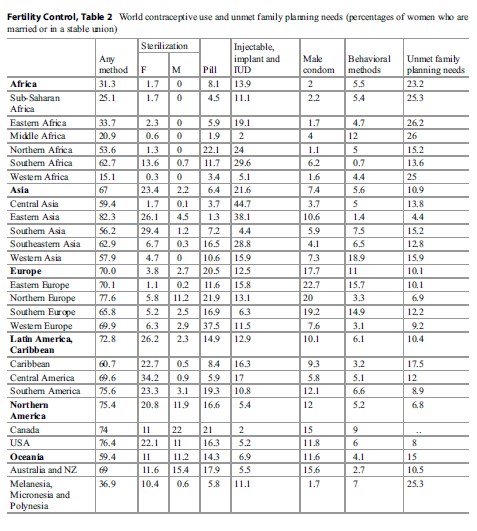

The United Nations has collected data on the percentage of women who use birth control among women who are married or in a stable union. In Asia, Europe, the American continents and Australia, and New Zealand, roughly two-thirds of women use contraceptives. In Africa, this situation is reversed, and there is a significant problem of unmet family planning needs.

Table 1. Typical use and perfect use effectiveness rates for contraceptives (chance of pregnancy expressed in percentages)

Table 1. Typical use and perfect use effectiveness rates for contraceptives (chance of pregnancy expressed in percentages)

In Asia, Latin America, and the USA, tubal ligation is the most popular birth control method, while vasectomy is more common in Canada. Among women in Asia and in East, North, and South Africa, injectables, implants, and the IUD are also very popular. European women rely especially on the pill, particularly in Western Europe, and on the male condom, especially in Eastern and Southern Europe, where behavioral methods are also popular.

The source did not collect or present data on EC.

For a few countries, the reader may notice a slight discrepancy between the figure in the first column (total number of women who use “any method”) and the sum of the figures for the various contraceptive methods. This discrepancy is explained by the use of vaginal barrier methods and other modern methods. In nearly all countries, the percentage of women who use these methods is zero or little more than zero (UN Population Division 2013) (Table 2).

Accessibility: Vulnerable Groups

There is evidence that some groups of women are particularly likely to encounter barriers to access to contraception, including minors, especially in middleand low-income countries, immigrants, racial minorities, and women who need EC (Dehlendorf et al. 2010; Alkema et al. 2013; Chandra-Mouli et al. 2014; Ceva and Moratti 2013).

Researchers have found that the barriers to access to contraception for these groups include the cost of contraceptive drugs and devices and laws and policies that limit the provision of birth control, especially to minors, or make contraceptives available only in pharmacies and with a medical prescription. The latter scenario renders access to contraception dependent on two factors: access to affordable healthcare services, which can be a problem for minorities, underprivileged and immigrant women, and the willingness or otherwise of healthcare workers to give contraceptive information or to prescribe contraceptives (Dehlendorf et al. 2010; Alkema et al. 2013; Chandra-Mouli et al. 2014). Healthcare workers’ attitudes to contraception can be a particularly serious obstacle for women who need EC, when the woman needs the contraceptive urgently and has little time to find another healthcare provider (Ceva and Moratti 2013).

Cultural factors also play a role. Married women in some middleand low-income countries, including married minors, are under pressure to conceive as soon as possible after marriage (Chandra-Mouli et al. 2014).

The Ethical Dimension

This paragraph presents the arguments used in the contraception debate. Some contraceptives also protect against STDs, but the focus here is on moral arguments that treat contraception as a fertility control rather than a disease prevention method, as the two questions are morally different.

The Natural Law Theory

The main argument against the use of contraception is based on the natural law theory, which postulates the existence of moral laws immanent to biological processes. Sexuality is seen as immoral, unless aimed at reproduction. In essence, the reasoning goes as follows: biologically, intercourse is the cause of conception, when a number of other necessary factors are also present; therefore, conceiving ought to be the moral goal of intercourse. This is an example of the naturalistic fallacy, where a moral duty (“ought to be”) is derived from a state of affairs (“is”). This theory has illustrious proponents. The early Christian theologian Saint Augustine taught that homosexuality, masturbation, and all sexual activities other than penile-vaginal intercourse were unnatural as they could not lead to pregnancy, and hence they were worse sins than fornication, rape, incest, or adultery.

Table 2. World contraceptive use and unmet family planning needs (percentages of women who are married or in a stable union)

Table 2. World contraceptive use and unmet family planning needs (percentages of women who are married or in a stable union)

The natural law argument is pseudo-empirical in that it postulates a moral duty, presenting a mere biological fact as the sole ethical and conceptual foundation of the duty. Biological phenomena can rise to the status of moral laws, only under the assumption that human beings have a moral duty not to interfere with the order of things as determined by God, or by a moral force immanent to natural phenomena. Structurally, the natural law argument is a syllogism, but its metaphysical premise remains implicit when the argument is used by secular thinkers and policymakers.

The birth control method championed by proponents of natural law theory is sexual abstinence. Pregnancy can be avoided by avoiding intercourse. This is based on the assumption that renouncing pleasure can be regarded as an acceptable birth control method, rather than as an unnecessary, major existential loss. The emotional and practical cost of abstinence to the individual is not taken into account.

Abstinence is also actively promoted by policymakers in Western countries. Until 2010, about 100 million dollars in US federal funds was spent annually on abstinence-only sex education aimed at unmarried young people (Knowles 2012).

In the past few decades, a new, mitigated version of the natural law argument has appeared. Proponents of the mitigated natural law argument predicate that sexuality is immoral unless it at least admits the possibility of conception. Natural, or behavioral, or traditional birth control methods have been championed by moral entrepreneurs. Behavioral methods consist of penis withdrawal before or without ejaculation, or of sexual abstinence that can be temporarily interrupted when the chance that the woman is fertile is very low. The woman can determine this by tracking her periods and by observing variations in her body temperature and in her vaginal mucus. Breastfeeding women also have a low chance of being fertile, until their periods have returned.

The main characteristic of natural methods is that they do not involve barrier devices or hormonal contraceptive techniques. With respect to most such devices and techniques, natural methods have a higher chance of leading to conception, even when used perfectly (see section “Effectiveness” above). Human interference with the natural order of things is thus kept at a minimum.

Taking The Right To Pleasure Seriously

Several arguments in favor of birth control have been advanced in the contraception debate; these are listed below in this paragraph. However, proponents of contraception share a common ethical assumption, an overarching moral belief that functions as a unifying factor among different types of pro-contraception arguments. The assumption is the following: individuals should not be expected to abstain from sex. The cost to the individual of foregoing pleasure to prevent conception, in terms of frustration and drastic lifestyle adjustments, is too high to be acceptable when alternatives exist. The possibility of not foregoing pleasure should carry some weight in moral evaluations.

It has also been argued that abstinence promoting policies are not effective (Stanger Hall and Hall 2011). Proponents of natural law theory maintain that abstention is a 100 % safe contraception method. It is indeed an indisputable fact that foregoing intercourse will certainly prevent an unwanted pregnancy, with the exception of nonconsensual sex, a topic beyond the scope of this entry. However, it is less indisputable whether individuals will indeed forego intercourse if required or recommended to do so by authority figures or policymakers. Accepting that sexuality is part of people’s lives, and adjusting expectations accordingly, is a more realistic expectation and is more likely to influence people’s behavior than teaching or preaching abstinence. History has demonstrated this.

During the early nineteenth century, most Western militaries actively promoted the use of condoms to their members, including in those countries where the advertising and sale of condoms to the general public were outlawed. Notable exceptions were the US and British militaries, which advocated abstinence. This policy affected STD prevalence, which was exceptionally high among American and British troops. Groups like the American Social Hygiene Association fought to prohibit condom use by military men, as well as by the general public. STDs were seen as the fair punishment for immoral behavior. The British military changed its policy during WWI, as the magnitude of the STD epidemics among British armed forces and its dire consequences became apparent. The British military started to promote condom use, which meant that the prevalence of STDs among British troops diminished, while it remained extremely high among American troops as the US military chose to retain its abstinence advocacy policy instead (Collier 2007).

The practical unfeasibility of abstinence is an empirical argument. However, in a heavily politicized and value-laden domain such as fertility control, an empirical argument is neither politically nor ethically neutral. Supporting contraception over abstinence as the lesser evil implicitly presupposes some degree of moral acceptance of contraception.

Acceptance of the right to pleasure is what characterizes all pro-contraception arguments, including the three main families of arguments in favor of contraception discussed below.

Self-Determination

The first set of arguments revolves around the notion of self-determination, which has been interpreted historically in two ways: self-determination of the individual and self-determination of the couple. The latter has been conceptualized by the US Supreme Court as an emanation of the right to privacy.

The moral and conceptual analysis of individual self-determination has been profoundly different historically depending on whether the individual is male or female. Modern contraception methods made their first appearance not as fertility control methods but rather as techniques used by male individuals to prevent STDs. Contraception was an instrument of men’s self-determination. It was only a few decades ago that contraception started to be seen as an instrument for the self-determination of the married couple and, later, of the individual woman, regardless of her marital status. Two rulings of the US Supreme Court illustrate this development (Stanger-Hall and Hall 2011).

The USA was the first country to introduce the birth control pill, in 1960 (see section “Hormonal Methods” above). However, in some US States, oral contraceptives were not available to all women until the advent of two Supreme Court rulings.

In Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 US 479 (1965), the Supreme Court invalidated a Connecticut law prohibiting the use of contraceptives, on the grounds that it violated the “right to marital privacy.” The right to privacy, not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, was held to be an emanation of other constitutional protections, including the right not to disclose information that might lead to one’s own incrimination. With Griswold v. Connecticut, the birth control pill became available to married women in all US States. In a nutshell, in moral-philosophical terms, the Supreme Court held that it is not admissible to infringe upon the sphere of moral autonomy and self-determination of the married couple by prohibiting it from using contraceptives.

In Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 US 438 (1972), the Supreme Court struck down a Massachusetts statute banning the distribution of contraceptives to unmarried people. The Court ruled that the statute violated the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits discrimination (Equal Protection Clause). With this ruling, oral contraceptives became available to unmarried women in all US States. With respect to Griswold v. Connecticut, the argument used in Eisenstadt v. Baird is profoundly different and radically innovative: the Court argued that reproductive self-determination is every woman’s individual right.

In conclusion, there has been a shift from seeing contraception as the individual right of a man to prevent STDs to a fertility control method that married couples are entitled to and onto the individual right of a woman. Several other facts could be brought to substantiate this claim. Margaret Sanger (1879–1966) was an early prominent American birth control activist, sex educator, and nurse. She opened the first birth control clinic in the USA and established organizations that later evolved into the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. By 1924, the condom was the most commonly prescribed birth control method in the USA. Condoms were then distributed in pharmacies with a medical prescription. One of the difficulties faced by Sanger as she fought for women’s right to birth control was that doctors would prescribe condoms to protect men from STDs, when they had premarital or extramarital intercourse. The men could not, however, get condoms to protect their wives from unintended pregnancy or STDs (Knowles 2012).

Women’s Health

Pregnancy, including pregnancies that end through miscarriage or abortion, has a deep impact on a woman’s body and her physical and mental health. It is the consequence of biological as well as social factors. The “women’s health” argument is specific to women as pregnancy does not directly affect men’s health. The use of barrier birth control methods directly impacts a man’s health only to the extent that it serves to prevent STDs, which is beyond the scope of this entry.

The “women’s health” argument cannot be regarded as a mere subdivision of the self-determination argument. It focuses on a woman’s physical and mental health and not on her moral or legal entitlement to choose her own reproductive path. The “women’s health” argument can rather be conceptualized as a corollary of a woman’s right to physical integrity. Such a right is slowly gaining acceptance, but it is still far from being universally accepted, as proven by statistics, public debate, and (lack of) legislation and adequate policies on various types of gendered violent crimes, including rape and harassment, domestic violence, female infanticide, mob violence, and traditional practices like female genital mutilation (UN General Assembly 2006). The right to physical integrity encompasses the right not to experience bodily invasions that a woman has not consented to and the right to avoid suffering to the extent that doing so is technologically and medically feasible. The latter can also be formulated as negative utilitarianism: the ethical and practical goal pursued is minimizing socially avoidable suffering.

In the 1930s, in his moral writings, philosopher Bertrand Russell stressed that too numerous pregnancies are known to be detrimental to the health of the woman. Moreover, Russell deemed it “undesirable, both physiologically and educationally, that women should have children before the age of 20” (Russell 1936). Still in 2014, major pregnancy and childbirth complications have a much higher incidence in teenage mothers than in mothers in their 20s and 30s and are the leading cause of death in girls aged 15–19 in middle and low-income countries (Chandra-Mouli et al. 2014).

There is an empirical-consequentialist version of the “women’s health” argument. Unwanted pregnancies may end in abortion. Abortion is likely to do more harm to a woman’s physical and mental health than contraception. For this reason, the empirical argument goes, birth control should be used as a means of abortion prevention.

Children’s Rights

This argument is based on the moral status of the hypothetical child that could be conceived without contraception. The potential person, who does not yet exist, is thus a moral stakeholder in the decision-making process. Several charters of children’s rights state that every child has the right to be born to parents who want them, love them, and are able to care adequately for them. The children’s rights argument appeals to the moral intuition of people with very different moral and religious outlooks and across very diverse cultures (Franklin 2001).

Conclusion

Access to contraception and information about it expands the scope of individual freedom. It empowers individuals, particularly women and children. It radically changes the degree of control that women have over their health, reproductive path, and lifestyle. It decreases socially avoidable suffering. However, in 2014, there are still important barriers to access to contraception. It is predicted that the use of contraceptives will grow, especially among disadvantaged groups and in poor countries.

Bibliography :

- A/61/122/Add.1. Available at http://www.un.org/ga/ search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/61/122/Add.1. Last opened 10 Nov 2014.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2013). World Contraceptive Patterns 2013. Available at http://www.un.org/ en/development/desa/population/publications/family/ contraceptive-wallchart-2013.shtml. Last opened 10 Nov 2014.

- Alkema, L., Kantorova, V., Menozzi, C., & Biddlecom, A. (2013). National, regional, and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: A systematic and comprehensive analysis. Lancet, 381(9878), 1642–1652.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (1965). Terms Used in Reference to the Fetus.

- Philadelphia: Davis. Ceva, E., & Moratti, S. (2013). Whose self-determination?

- Barriers to access to emergency hormonal contraception in Italy. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 23(2), 139–167.

- Chandra-Mouli, V., McCarraher, D. R., Phillips, S. J., Williamson, N. E., & Hainsworth, G. (2014). Contraception for adolescents in low and middle income

- De Beauvoir, S. (1949). Le Deuxième Sexe. Paris: Gallimard. English edition: De Beauvoir, S. (2011)

- The Second Sex. New York/Toronto: Vintage. Jutte, R. (2008). Contraception: A History. Cambridge, UK/Malden: Polity.

- Russell, B. (1929). Marriage and Morals. London: George Allen and Unwin.

- Vlassoff, C. (2013). Women and contraception. In N. P. Stromquist (Ed.), Women in the Third World: An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Issues (pp. 185–193). New York/Oxford: Routledge. countries: Needs, barriers, and access. Reproductive Health, 11(1), 1.

- Collier, A. (2007). The Humble Little Condom: A History. Amherst: Prometheus Books.

- Dehlendorf, C., Rodrigues, M. I., Levy, K., Borrero, S., & Steinauer, J. (2010). Disparities in family planning. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(3), 214–220.

- Franklin, B. (2001). The New Handbook of Children’s Rights: Comparative Policy and Practice. Oxford: Routledge.

- Knowles, J. (2012). A History of Birth Control Methods. New York: The Katharine Dexter McCormick Library and the Education Division of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

- Noé, G., et al. (2010). Contraceptive efficacy of emergency contraception with levonorgestrel given before or after ovulation. Contraception, 81(5), 414–420.

- Russell, B. (1936). Our sexual ethics. The American Mercury, 149(38), 36–40.

- Stanger-Hall, K. F., & Hall, D. W. (2011). Abstinence-only education and teen pregnancy rates: why we need comprehensive sex education in the U.S. PLoS ONE, 6(10), e24658.

- Trussell, J. (2007). Contraceptive efficacy. In R. A. Hatcher, J. Trussell, & A. L. Nelson (Eds.), Contraceptive Technology: Twentieth Revised Edition (pp. 779–863). New York: Ardent Media.

- UNAIDS, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (2004). Making condoms work for HIV prevention: UNAIDS best practice collection. Available at http:// data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub06/jc941-cuttingedge_ en.pdf. Last opened 10 Nov 2014.

- United Nations General Assembly (2006). In-depth study on all forms of violence against women. Document

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.