This sample Health Literacy Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Health literacy is an increasingly essential competency required of today’s citizens. Similar in nature to literacy, in general, adequate health literacy is associated with better health outcomes than inadequate or low health literacy. Encompassing a broad array of overlapping skills, health literacy can impact one’s ability to obtain health services, especially high-quality timely and tailored health services, as well as the ability to act on desirable health recommendations. In the context of health equity issues, and the notion of health as a human right, health literacy is increasingly identified to be of paramount importance, and those who lack the will to foster a health literate citizenry are likely to see wider health gaps and disparities than we see today. This essay describes the concept of health literacy, its importance as a health access and management issue, and the bioethics of failing to counter low health literacy wherever it exists.

Introduction

Health literacy, a multidimensional form of literacy, encompasses the capacity to obtain, process, and act on basic health information (Clark 2011). Strongly linked to individual health outcomes (Williams et al. 2002), health literacy can impact community-wide health efforts directed to the public as a whole plus the timely attainment of desirable and sustainable public health goals, among other factors (Gazmarian et al. 2005). Indeed, adequate health literacy seems crucial in today’s world as far as helping the public to obtain and access needed health services, for co-decision-making in the context of treatment, for providing helpful support to others concerning their health, for enacting positive health behaviors, and for positively influencing provider-client communication processes.

Health literacy also influences the effective use of mass media to communicate health imperatives, the ability to utilize social media health applications and to critically evaluate health marketing messages. As outlined by Clark (2011), health literacy is key to the ability to make effective, appropriate, responsible individual health as well as collective decisions, to appraise the credibility of information and its relevance, and to effectively act on the information and navigate increasingly complex physical as well as virtual health systems and applications. Applying recommendations to self-manage complex health conditions on a day-to-day basis in a self-determined manner is also strongly influenced by the magnitude of a person’s health literacy. A crucial skill – especially for those who reside in countries without standard access of care for all policies – health literacy not only encompasses a person’s ability to understand their rights but also affects the ability to effectively advocate for their health needs, and the ability to become an educated consumer and empowered patient able to engage in effective two-way communications with a provider.

The three overlapping features of health literacy, involving the ability to obtain health information; interpret tests, dosages and instructions, insurance and informed consent documents; and apply the information, all of key importance in today’s increasingly complex health care realm, are not a given however in most populations including the United States. As well, the ability to understand medication labels, medication contraindications, and appointment cards along with one’s legal rights are other key features of this competency.

This essay aims at describing the problem of low health literacy, some possible solutions, and the relationship of this problem to bioethics. Drawn from 50 years of research, the importance of health literacy, which includes three overlapping perspectives, basic literacy or comprehension, interactive/participatory literacy, and critical literacy-involving analysis and action, is clearly growing each year. Yet, many challenges remain that have an array of implications for both providers and patients, as well as policymakers and ethicists, especially in the context of health disparities, and the urgent need to curtail the burgeoning prevalence of preventable chronic diseases, and the costs, often passed on inadvertently to others.

Populations Exhibiting Low Health Literacy Levels

Although one of the fundamental public health challenges in the twenty-first century is the improvement of people’s health literacy, populations commonly experiencing poor health literacy remain the elderly, racial and ethnic minorities, those with low levels of educational attainment, those with low incomes, and those with compromised health status (Gazmarian et al. 2005; Lubetkin et al. 2015) or chronic diseases (Volandes and Paasche-Orlow 2007). As well, even though health literacy is fundamental to well-being in the twenty-first century, many adults and youth worldwide are currently either health illiterate or only marginally “health literate,” and children who depend on their parents may suffer additional challenges if their parents cannot read, understand, or comprehend health directives.

Volandes and Paasche-Orlow (2007) suggested limited health literacy affects one in three health consumers. This situation is frequently compounded because patients are often too embarrassed to admit their limited understanding, even though they are commonly those who have the highest rates of chronic disease, drug use and abuse, and infant mortality rates. They may also have limited health insurance access, or access to quality health care and health care resources, as well as limited skills to carry out positive health behaviors and to overcome negative behaviors.

Bioethics

The ethical delivery of optimal and equitable health services, and resources, is highly valued by most societies today. Yet, ample research shows many citizens may not be able to take full advantage of prevailing services and opportunities for maximizing their health, even if they are forthcoming, as a result of their limited proficiency in a variety of health communication and comprehension-related spheres. In many cases, even when it may be critical to reach all members of the public to provide important preventive information, such time-sensitive materials may not result in the intended goal if the health information cannot be readily understood and acted on. Beneficence is the obligation of health care professionals to do everything possible to improve people’s health. Coupled with the principle of justice, beneficence stresses the need to promote equal health opportunities for all citizens. This is not readily achieved in the presence of factors extrinsic to the health care system that can affect the uptake of health information, such as having limited health literacy skills. Health illiteracy thus seems a key barrier to applying basic ethical principles of health care including nonmaleficence.

As a result, addressing a nation’s health literacy levels has become both a moral imperative as well as an ethical social responsibility (Jotkowitz and Porath 2007). In this respect, efforts to enhance the health literacy skills of recipients of health communications, having a clear understanding of the impact of health literacy on equity and justice issues, as well as knowledge as to who is at high risk in this respect is of great import. As well, the ability to test health literacy and provide appropriate materials and information to the patient that can be acted on and understood is clearly desirable. Policymakers too cannot ignore the link between social factors that promote or hinder health literacy skills, such as educational gaps and inequities, plus the excess economic and societal burden of not acknowledging this issue. Unfortunately, the desired understanding of this health literacy issue by providers and policymakers is not a given.

Outcomes Of Low Health Literacy

Ample research shows that low or inadequate health literacy significantly impacts an individual’s ability to participate actively in the health decision-making realm, to critically reflect on their options and personal situation, and to carry out desired self-management strategies (Nairn 2014). In the context of ethical health care practices, unrecognized health literacy also impacts a patient’s ability to detail her/his history adequately, and consequently the provider’s ability to foster the care required. It can also affect a client’s dignity and understanding of his or her entitlements and rights.

Low-health-literate-minority populations may be especially disadvantaged if they have limited access to culturally appropriate as well as linguistically appropriate information and support services. They may consequently be more likely than not to place some or a lot of trust in persons such as family members, friends, and religious leaders or organizations who may not be good referents in the context of health issues (Lubetkin et al. 2015). In turn, those who have no knowledge or limited knowledge of a preventable disease are not likely to act on this, or understand how to do this.

This inability to avoid preventable disease and injury situations not only has far-reaching bioethical implications but is extremely costly to the individual and society. In particular, many today cannot take effective health steps, because they are uneducated, and/or don’t read or write in the dominant language medium. They may consequently be unable to access and/or process information, make effective decisions, know their rights and be able to access these, or make a contribution to the health care visit (Nairn 2014). The fact that those with low health literacy commonly have lower health status than those with higher health literacy is true across acute and chronic diseases. Moreover, those with low health literacy may seek treatment at later rather than earlier stages of the disease. They may consequently have higher hospitalization rates, higher multimorbidity rates, a shorter life expectancy, and worse health status. Their increased incidence of chronic illness, a higher risk of death, and deleterious health impact may be commensurate with that of having diabetes (Volandes and Paasche-Orlow 2007).

Some of the additional adverse outcomes of low health literacy that have implications for the equitable attainment of health outcomes for all are

- Medical errors (Clark 2011; Nairn 2014)

- Infrequent, less optimal, or inappropriate use of health care services (Volandes and PaascheOrlo 2007)

- Lower quality or perceived quality of care (Hasnain-Wynia and Wolf 2010)

- Poorer ability to recall information (McCarthy et al. 2012)

More than a decade ago, Williams et al. (2002) found a greater lack of understanding of clinical instructions in patients with low health literacy, when compared to those with adequate literacy. This should not be surprising given the challenging topics today’s patients are often asked to comprehend, the complexity of the approaches used to treat these conditions, and the many logistical barriers to carrying out the recommended behaviors and accessing the required resources in all these realms.

The autonomy of low–health literacy health care users may also be jeopardized if forms such as consent forms, patient’s bill of rights, advanced directives, and memos about privacy protection are inaccessible (Volandes and Paasche-Orlow 2007) and the provider is not aware of the importance of health literacy in fostering health outcomes.

Implications For Bioethics

As an offshoot of literacy, health literacy, which affects high numbers of health care users worldwide, should be of interest to all health care providers, as well as policymakers interested in improving the health and successful aging of the populace across the lifespan. As a legal issue, less has been done in the realm of health literacy to assure quality and access (Clark 2011). In this regard, Schillinger (2007) applauded the efforts of Volandes and Paasche-Orlow (2007) for presenting a sound argument as to the untoward adverse health effects of limited literacy as reflective of a systematic form of injustice on the part of health care delivery systems that assumes those using the system are literate. As Shillinger claims, this argument is important and a vital component of a bigger moral imperative to reverse the “inverse care law,” where resources are distributed unequally to those in greatest need, a problem that requires a sound well-studied and practical solution according to Jotkowitz and Porath (2007).

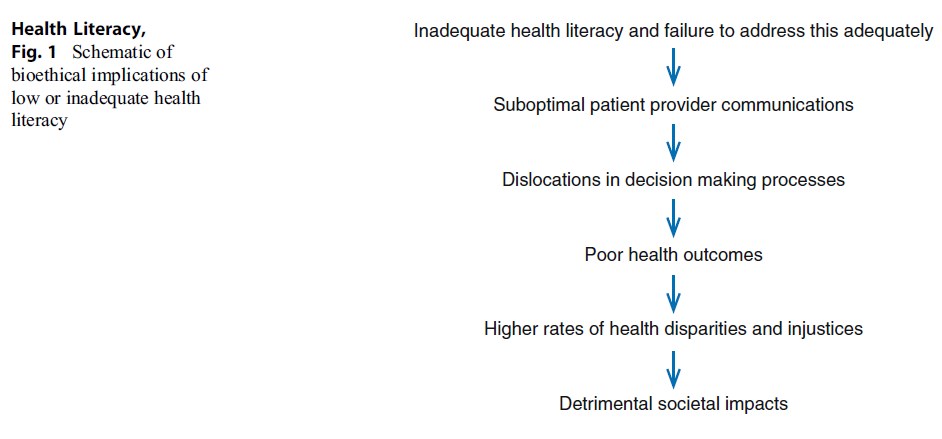

With its roots in the bioethical principles of autonomy, justice, and beneficence, health literacy also entails the ability to provide informed consent, the right to quality care, and to antidiscrimination (Clark 2011). Unfortunately, in addition to provider ignorance of health literacy issues, as Shillinger reports, the gap between those with and without adequate health literacy is commonly magnified if a patient has a poor grasp of provided information or fails to provide important information or both. As well, this can impede a clinician’s efforts to deal effectively with their patients in a consistent and optimal manner, and both can have far-reaching bioethical implications within and external to their day-to-day practices (see Fig. 1).

Policy changes at both the macro and micro levels that can address the multiple sources of health illiteracy are increasingly important. Policies that permit more optimal ethical day-to-day health provider practice opportunities, such as the ability to devote more time to patients with health literacy challenges, as well as resources to do this, would potentially reduce the health disparities gap that prevails in many spheres (Misra-Hebert and Isaacson 2012), while reducing the health care burden attributable to low health literacy.

Figure 1 Schematic of bioethical implications of low or inadequate health literacy

Figure 1 Schematic of bioethical implications of low or inadequate health literacy

In this context, clinicians and others are urged to become aware of and sensitized to this prevalent problem because

- An individual’s health literacy may be worse than their general literacy or their ability to read, write, and speak in their native language and is not always immediately apparent.

- Not having adequate reading and/or numeracy skills could affect an individual’s ability to understand concepts/tasks necessary for their own optimal health, as well as the health of significant others.

- It could affect access to necessary information, the ability to interpret the information accurately, access to quality care, and the ability for optimal self-care.

A study of 2,659 outpatients at two US hospitals showed 42 % did not understand instructions to “take medication on an empty stomach” and 49 % could not determine whether they were eligible for free care from reading a hospital financial aid form.

The same study also found a 52 % increase in the risk of hospitalization among patients with inadequate literacy compared with patients with adequate literacy. It was also noted that 42 % patients did not comprehend basic instructions, while 26 % did not understand appointment slips, and 60 % did not understand informed

Detrimental societal impacts consent form procedures. Thirty-five percent of the English-speaking patients had inadequate or marginal functional literacy, and the figure was higher for the Spanish-speaking patients (Williams et al. 1998a)

Williams et al. (1998a) also assessed the relationship between functional health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease in a cross-sectional survey of patients with hypertension and diabetes. They found almost half of the patients had inadequate functional health literacy levels and were less likely to know basic information about their diseases and essential self-management skills than those with high functional health literacy scores. Only 50 % of the low-literacy patients with diabetes knew the symptoms of hypoglycemia compared with 94 % of those patients with adequate literacy levels. Another study published by Williams et al. (1998b) examined the relationship between literacy and asthma knowledge and self-management skills. In this convenience sample of 483 patients, lower literacy levels, as measured by the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), were associated with lower asthma knowledge scores and improper asthma self-management.

Challenges

In addition to relatively few efforts over the past 15 years to uncover sources of health illiteracy, problems arise in efforts to both identify as well as intervene effectively in the context of health literacy deficiencies. Not only is there ignorance of this important public health sphere, along with a commonplace assumption that the populace has high health literacy and that universal precautions improve knowledge acquisition among patients (Gordon and Wolf 2007), but measuring health literacy and obtaining the personnel and resources to address low health literacy where it is identified remain problematic. In parallel with the failure over the last 15 years to strategically address the sources of health illiteracy, the increasing prevalence of complex chronic health conditions requiring individual daily self-management, the complexity of the physical and virtual organizations needed to support these efforts, the multiple resources that must often be navigated, plus linguistic challenges in a monolingual society are a few additional challenges. Stigma, shame, and fear as important personal factors precluding disclosure of literacy limitations and limited provider understanding of this topic remain.

Conclusion

Limited health literacy, which impacts one’s ability to understand, access, and act on health information, may be responsible for heightening the immense gap between the haves and have-nots in society in terms of health status. Limited health literacy may also seriously impact the patient’s understanding of their rights, their ability to access their rights, their ability to be part of the decision-making process, and their ability to navigate today’s complex health environments and to use advanced technologies. More often than not, health illiteracy seriously hampers a wide range of disease prevention efforts, especially the enactment of timely and accurate responses to various health recommendations. While clearly an issue with far-reaching bioethical and social implications, it appears the bioethical aspect of this topic has received little attention (Volandes and Paasche-Orlow 2007). However, from an examination of the available literature, it is concluded that the problems of low health literacy will persist unless the importance of the issue is more strongly stressed. For example, providers need to be apprised of the possible literacy challenges of their patients, since these may not be obvious. Another step is to render health information materials accessible to the individual through careful analysis of their health, cultural, and cognitive attributes. Careful editing of complex instructions, where indicated, and explaining how to interpret information such as blood pressure or glucose content readings may also be helpful. As well, reducing the volume of materials; using charts, short sentences, and pictures; and avoiding complex terminologies and/or Internet information is also advocated for those whose literacy levels are challenged.

Others strategies might include the creation of a shame-free environment, a teach-back instruction method (Nairn 2014), an improved education system for all including medical personnel, better screening of potential problems, and policyrelated changes.

Also helpful may be minimizing the cognitive burden patients might face when trying to manage their personal health, speaking in plain everyday terms (Nairn 2014), staff training, clearer instructions and help with completing forms, and adopting a universal assumption of limited health literacy among populations utilizing the health care system (Volandes and Paasche-Orlow 2007). Increasing the diversity and language capacity of the workforce (Schillinger 2007), reducing childhood education inequalities, the use of surrogate readers, computer-assisted interactive technology, and pictorial presentations may be helpful as well.

In sum, addressing the problem of widespread health illiteracy is paramount in the context of ethical practice in today’s health arena, including efforts to minimize the growing epidemics of obesity, diabetes, school bullying, and risky behaviors and others that affect young and older citizens. Yet, current modes of health delivery often assume clients understand and can readily act on health recommendations, thus potentially producing preventable injustices and inequalities. By contrast, targeted efforts that promote health literacy and those that can enable all citizens to make beneficial, rather than poor, health-related choices may have far-reaching social benefits, as well as ethical practice benefits. With roots in the bioethical precepts of beneficence, justice, the right to quality care, and autonomy (Clark 2011), the term health literacy has thus become one of the central aspirations of citizenship in the postindustrial era (Marks 2009). Greater provider awareness of the impact of low health literacy on health outcomes, supported by sound educational and health policies, will undoubtedly enable patients to obtain a high life quality more readily, while minimizing the multiple adverse bioethical implications of failing to do so (McCarthy et al. 2012).

Bibliography :

- Clark, B. (2011). Using law to fight a silent epidemic: The role of health literacy in health care access, quality, & cost. Annals of Health Law, 20(2), 253–327. 5 p preceding i.

- Gazmarian, J. A., Curran, J. W., Parker, R. M., Bernhardt, J. M., & DeBuono, B. A. (2005). Public health literacy in America. An ethical imperative. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28, 317–322.

- Gordon, E., & Wolf, M. (2007). Beyond the basics: Designing a comprehensive response to low health literacy. American Journal of Bioethics, 7(11), 11–13.

- Hasnain-Wynia, R., & Wolf, M. S. (2010). Promoting health care equity: Is health literacy a missing link? Health Services Research, 45(4), 897–903. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01134.x.

- Jotkowitz, A., & Porath, A. (2007). Health literacy, access to care and outcomes of care. American Journal of Bioethics, 7(11), 25–27; discussion W1-2.

- Lubetkin, E., Zabor, E., Isaac, K., Brennessel, D., Kemeny, M., & Hay, J. (2015). Health literacy, information seeking, and trust in information in Haitians. American Journal of Health Behavior, 39(3), 441–450.

- Marks, R. (2009). Ethics and patient education: Health literacy and cultural dilemmas. Health Promotion Practice, 10(3), 328–332.

- McCarthy, D. M., Waite, K. R., Curtis, L. M., Engel, K. G., Baker, D. W., & Wolf, M. S. (2012). What did the doctor say? Health literacy and recall of medical instructions. Medical Care, 50(4), 277–282. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318241e8e1.

- Misra-Hebert, A. D., & Isaacson, J. H. (2012). Overcoming health care disparities via better cross-cultural communication and health literacy. Cleveland Clinical Journal of Medicine, 79(2), 127–133. doi:10.3949/ ccjm.79a.11006.

- Nairn, F. T. (2014). What we have here is a failure to communicate. The ethical dimension of health literacy. Health Progress. Retrieved from http://www.chausa. org/publications/health-progress/article/july-august-2014/ethics—the-ethical-dimension-of-health-literacy

- Schillinger, D. (2007). Literacy and health communication: Reversing the “inverse care law”. American Journal of Bioethics, 7(11), 15–18.

- Volandes, A., & Paasche-Orlow, M. (2007). Health Literacy, health inequality and a just healthcare system. American Journal of Bioethics, 7(11), 5–10.

- Williams, M. V., Baker, D. W., Parker, R. M., & Nurss, J. R. (1998a). Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease. A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(2), 166–172.

- Williams, M. V., Baker, D. W., Honig, E. G., Lee, T. M., & Nowlan, A. (1998b). Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest, 114(4), 1008–1015.

- Williams, M. V., Davis, T., Parker, R. M., & Weiss, B. D. (2002). The role of health literacy in patient-physician communication. Family Medicine, 34(5), 383–389.

- Bo, A., Friis, K., Osborne, R. H., & Maindal, H. T. (2014). National indicators of health literacy: Ability to understand health information and to engage actively with healthcare providers – A population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health, 14, 1095. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1095. Physicians Foundation, & SDSMA Center of Physician

- (2014). Low health literacy: A hidden epidemic. South Dakota Medicine, 67(6), 239.

- Sentell, T. (2012). Implications for reform: Survey of California adults suggests low health literacy predicts likelihood of being uninsured. Health Affairs (Millwood), 31(5), 1039–1048. doi:10.1377/ hlthaff. 2011.0954.

- Tamariz, L., Palacio, A., Robert, M., & Marcus, E. N. (2013). Improving the informed consent process for research subjects with low literacy: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(1), 121–126. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2133-2.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.