This sample Law And Bioethics Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

When we, more or less, all shared the same values on which we based our societies and we largely turned to a shared religious base to define those values, ethics, as a separate and identified enquiry and analysis, did not play a clearly identified role. That is no longer true in secular Western democracies, which are multiethnic, multireligious, and very diverse, and are facing unprecedented challenges, many arising from new scientific discoveries, to traditional shared values. We have moved from simply assuming the law embodied our ethics and values to examining the compatibility of any given law with ethics to considering ethics first and law second in order to allow ethics to inform the law. Understanding the relation and interaction of law and bioethics is essential in making wise decisions about how to implement and govern what we may and must not do if we are to maintain a values base that will result in future societies in which reasonable people would want to live. Just as we can damage and even destroy our physical ecosystem, we can do the same to our metaphysical ecosystem, the principles, values, beliefs, attitudes, and so on, on which we found our societies.

Introduction

Far from everyone agrees on what is the contemporary relation of law and ethics, and whether ethics is benefiting or harming the law. To decide, we must address questions that include: Why does the relation of law and ethics matter? What is its history? Why did “applied ethics” and its practitioners emerge in the 1970s? And what is the contemporary interaction of law with applied ethics, especially in courts and legislatures?

History Of Interactions Of Law, Ethics, And Medicine In Courts

A judicial observation describing the relation of law and medicine in the early 1970s, namely, “Law, marching with medicine but in the rear and limping a little,” can give us a window on how ethics came to the aid of law to help it to keep up with medicine and can help us to understand the development of the relation of law and bioethics. The quotation comes from the judgment of Justice Windeyer of the High Court of Australia in the case Mount Isa Mines v Pusey ((1970) 125 CLR 383), an early case – 1970 – in which the judge recognized that the law was clearly not keeping up with advances in medical science, in this case, with advances in psychiatry. With hindsight, we can see in this case ethics coming to the law’s aid, informing and supplementing it, when the law was having difficulty coping – in the sense of justice prevailing – although ethics would not have been perceived as playing that role at the time.

The legal issue for the court was whether the seriously psychiatrically injured plaintiff could recover damages for negligently inflicted “pure nervous shock,” that is, mental injury unaccompanied by physical injury. Historically, the Anglo-Australian Common Law did not allow recovery for such damages. The fears of allowing compensation were that, once this happened, there would be a flood of cases overwhelming the courts and that fraudulent claims would be presented.

First the judge took note of the many then relatively recent psychiatric advances in recognizing and diagnosing mental illness. It’s a truism in ethics, but no less important for being so, that “good facts are necessary for good ethics.” That means as the facts, especially medical and scientific facts, change, so do the ethics change. And, consequently, so sometimes should the law. Using a medical advance as a justification for changing the law to allow an award of damages for “pure” mental injury, when that was ethically required, was an early example of a court incorporating ethics into law in order to deal with advances in medical science, a practice that was to become common, as is discussed later in this entry.

Justice Windeyer’s statement that the law was “in the rear and limping” is an articulation of a disconnect that he perceived between, on the one hand, what ethics required in terms of compensating the plaintiff for his serious psychological injuries and, on the other hand, that the law, as it stood, would not allow that.

It’s probably not a coincidence that this judgment was handed down in 1970. This was the era when the development of the field of practice, research, and scholarship that we now know as “applied ethics” of which bioethics is the paradigm example was just beginning. Its emergence was being precipitated by unprecedented advances in science and medicine with which the law had no experience and for which it had no precedents, yet physicians, scientists, politicians, policymakers, and the public were turning to the law, in both courts and legislatures, for guidance in relation to the development and use of these advances.

Emergence Of Applied Ethics And Ethicists

Prior to around 1970, there was a tacit assumption within each society that we more or less agreed on the collective values on which our societies were based – that is, what was and was not moral and ethical – and that the law reflected, implemented, and upheld these values. In the late 1960s, as challenges to traditional shared values emerged and conflict as to what they should be erupted, many societies realized that this assumption was no longer valid.

The causes in Western democracies included that people no longer largely shared a Judeo-Christian religious tradition to which they would turn for guidance on values. Many were not religious or, if they were, they followed an increasingly wide variety of religious traditions. Another cause was that we did not agree on the values that should govern the mind and world-altering breakthroughs being realized in the new science (Somerville 2006).

Science fiction was rapidly being converted to science fact: the previously impossible, and even unthinkable, was becoming reality, and we had no precedents for the values that should govern these extraordinary developments. A seminal event in the emergence of what became the new field of applied ethics was the first heart transplant in 1967 by Dr. Christiaan Barnard in South Africa. A person was walking around with a beating heart, the primary indicator of life, of a dead person.

The law was confronted with questions such as: Was it murder to have taken the donor’s heart? When was a person dead so their organs could be taken for transplantation? Should organ transplants be prohibited? If not, under what conditions were they acceptable? Today, we regard organ transplantation as being such a routine medical procedure that we easily forget how shocked and deeply concerned the world was to learn of Dr. Barnard’s feat.

A second seminal event was the birth of the first “test-tube baby,” Louise Brown, in 1978. Once more, the world was shocked at a procedure that involved conception other than through sexual intercourse and outside a woman’s body that, again, is routine today. Questions that emerged in this context included: Was it acceptable to freeze human embryos? What about using them for experimentation? Should embryo donation be allowed? Should a surrogate mother be allowed to keep the baby to which she gave birth but was not genetically related? And so on.

Science was moving too fast for the law and the courts to keep up with the unprecedented issues it was presenting. And the number of those issues exploded through the 1980s and into the 1990s – and, of course, has continued to do so. The courts – and, indeed, legislatures – when faced with such issues coped by turning to ethics as an “add-on” to the law. They would first look to the law, and if this did not provide a clear or satisfactory answer, they would turn to ethics which was growing exponentially. Anecdotally, it’s said that in 1970 there were seven articles published in the world in English in the field we would now call applied ethics. In 1980 there were 14 specialty journals in the field. And by 1990 there were over 200 ethics centers, many of them in universities, undertaking teaching and research in the field.

Moreover, increasingly, “ethicists,” in particular, bioethicists, who were, at the time, starting to be recognized as professionals in applied ethics were called upon. They became involved as expert witnesses before official enquiries, courts, and parliamentary committees (Somerville 2000). The question of what credentials should be required in order to be regarded as such an expert remains to this day a contentious one.

Chief Justice Robert French of the High Court of Australia discusses this question in an interesting article, published in 2003 (French 2003). He begins by recognizing the by then well-established interaction of law and applied ethics in relation to issues raised by scientific and medical advances and notes “an increasing reliance on ethicists as public policy life coaches to guide us on our way.” He proposes that those ethicists must be, at the least, honest, objective, independent, competent, and diligent in providing “transactional advice in the formulation of administrative practice and public policy and in the development of the law.” In other words, the Chief Justice clearly contemplates a valid role for ethics – and ethicists – in the law’s future. He rightly warns, however, that “[a]ny tendency to commercialization or commodification of ethics as a product is damaging to the whole of society. So too is the corruption of ethics to a form of politically convenient certification of proposed actions, practices or laws.” He goes on to note that “[t]here may be a need to develop ethics for ethicists,” a sentiment with which I’m sure all ethicists, and many others, would concur.

The first clearly identified use of ethics in law and the emergence of the disciplinary field known as “applied ethics” and its practitioners, “ethicists,” was initially largely in the area of bioethics. Later “applied ethics” analysis was expanded to other areas where concerns about ethics arose, when bioethics became used as a model for addressing them.

To return to the history of the development of applied ethics, it’s arguable that in the early 1990s the order of analysis changed from analyzing from law to ethics to first looking at the ethics and then assessing whether the law accorded with the ethics. This change might seem of little importance and largely irrelevant, but its effect was far from neutral on the outcome of decisions that involved both ethical and legal analysis. Law informing ethics does not necessarily result in the same outcome as when ethics informs law. This is easily seen in relation to physicians’ decisions about offering adequate and effective pain management treatment to patients in pain.

In the past, many physicians interpreted the criminal law as prohibiting them from giving necessary pain relief treatment, if they believed there was any chance it might shorten the patient’s life (or in the case of some physicians, that it might cause addiction) and they would withhold such treatment. Yet, it is unethical for a physician to unreasonably leave a person in serious pain; ethics requires that all reasonably necessary pain relief treatment be offered to a patient.

When the order of analysis was changed from law informing ethics (law first, ethics second) to ethics informing law (ethics first, law second), the law was correctly seen by physicians and others as not prohibiting the provision of such treatment. Indeed, we now recognize it is a breach of human rights for a healthcare professional to leave a person in serious pain and it can be argued there is a legal duty to offer adequate pain management to patients who need it. This approach is articulated and implemented in the 2010 Declaration of Montreal, discussed below, which provides a paradigm example of the interaction and relation of law and bioethics.

Finally, in this section, the American Medical Association Opinion 1.02 – The Relation of Law and Ethics merits noting in the context of the current discussion. It provides, The following statements are intended to clarify the relationship between law and ethics.

Ethical values and legal principles are usually closely related, but ethical obligations typically exceed legal duties. In some cases, the law mandates unethical conduct. In general, when physicians believe a law is unjust, they should work to change the law. In exceptional circumstances of unjust laws, ethical responsibilities should supersede legal obligations.

The fact that a physician charged with allegedly illegal conduct is acquitted or exonerated in civil or criminal proceedings does not necessarily mean that the physician acted ethically.

Contemporary Examples Of The Interaction Of Bioethics And Law

Ethics Informing Law: Mandating Pain Management

The Declaration of Montreal, which was shepherded to fruition by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), establishes that people in pain have a “fundamental human right” to have reasonable access to pain management and that unreasonable failure to provide such access is a breach of their human rights.

Why Turn To Human Rights?

The language of human rights is very persuasive and is a language common to ethics and to law; as such, it can bridge gaps between them. It’s difficult to imagine any reasonable person saying, “I don’t care about human rights or if they are breached.” Recognition of human rights, whether in domestic or international law or, indeed, in ethics, tries to ensure the rightness or ethics of our interactions with each other at the most basic level of our humanness, at the level of its essence, that which makes us human – which is not easy to define. As French philosopher Helene Boussard writes, “both human rights law and bioethics aim to protect human dignity, from which human rights values stem” (Boussard 2005). Intentionally leaving someone in serious pain is a complete failure to respect their human dignity, and therefore, it is appropriate to bring both human rights law and bioethics to bear to try to prevent such situations from occurring. That is exactly the goal of the Declaration of Montreal.

The Nature Of Human Rights

Through the use of the concept of human rights the Declaration spans and connects law and bioethics, because as noted already both law and bioethics are closely connected with human rights.

While human rights are often legally enacted the law does not create human rights; rather, they exist independently of being recognized by any human agency. That is why no one can opt out of respecting them. What we do is articulate human rights. And that’s why statements of them are called declarations.

This noncontingent feature of human rights also means that private actors can proclaim them, as is true in regard to the Declaration of Montreal.

In speaking of other declarations dealing with ethics in scientific and medical contexts, such as UNESCO’s Declaration on Universal Norms on Bioethics, Boussard explains well the nature of such declarations. She says they

are legal instruments but they are not legally binding. Their originality lies in their aim, which is to translate ethical standards into legal terms in order to protect human rights in scientific research and medical interventions. .. .[B]ioethics and law strengthen each other to give teeth to fundamental human rights values. .. . [T]hey are ethically inspired legal instruments. (Boussard 2005)

This last sentence, which articulates and emphasizes the symbiotic relation of bioethics and law, deserves to be strongly endorsed.

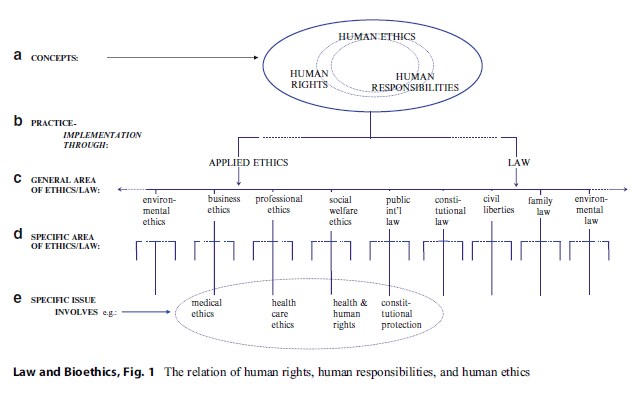

One way to understand the term “human rights” is as shorthand for a tripartite concept that consists of human rights, human responsibilities (or obligations), and human ethics. Sometimes we need to focus on one of these limbs, sometimes on another, and sometimes on all of them. A chart is included which explains this tripartite concept diagrammatically (see Fig. 1). As this shows, human rights, human responsibilities, and human ethics can be seen as three different entry points into the same reality, situation, or issue. It also shows why we can speak of human ethics, which can later be translated into legally recognized human rights, before that legal recognition occurs.

An advantage of such an approach is that, as Boussard states, recognizing the “interdependence between human rights law and bioethics leads us to move from a static image of existing or positive law in favour of a more dynamic concept in which views on law as it is and views on law as it should be are continually merging into views on law as it is becoming.” So, recognizing a human right to reasonable access to pain management means, for instance, that healthcare professionals and healthcare institutions have ethical and sometimes legal obligations to offer patients such management.

The Nature And Impact Of The Declaration

Although human rights obligations exist whether or not we declare them, declaring them and, even more potently, formally enacting them as law helps to ensure that they are honored and not breached. The hope is that the Declaration will help to change the horrible reality of people being left in pain.

The Declaration will be an ethics guide in relation to pain management and an educational tool for healthcare professionals and trainees. Sometimes, it will function as evidence to justify giving necessary pain relief treatment, when others would prevent that. In particular, it will help to overcome the harmful beliefs of some healthcare professionals who, as I mentioned previously, withhold pain management because they fear legal liability or that patients will become addicted. It will deliver a strong message that it’s wrong not to provide pain management, not wrong to provide it.

Figure 1. The relation of human rights, human responsibilities, and human ethics

Figure 1. The relation of human rights, human responsibilities, and human ethics

Provisions in the Declaration could become case law if adopted by courts, which would mean failure to live up to its requirements could constitute medical malpractice (medical negligence) or unprofessional conduct, which can be cause to revoke a physician’s license to practice medicine.

And the Declaration will inform and one hopes guide institutions and governments in formulating health policy and law with respect to pain management. It will help Governments to understand that they have both domestic and international obligations, at the very least, not to unreasonably hinder either their own citizens’ or other people’s access to pain management.

It is an outrage and a human tragedy that, in developing countries, many people in serious pain do not have access to opioids, including as a result of the conditions relating to narcotic drugs some countries attach to their foreign aid to these developing countries. An egregious example of a lack of access to pain management in a developing country is documented in a report from Human Rights Watch. The vast majority of children dying from HIV/AIDS in Kenya die with no pain relief treatment (Human Rights Watch 2010). This is clearly an area where ethics must inform law and practice.

Wider Impact Of The Declaration Of Montreal On Human Rights

And, finally, the Declaration of Montreal could raise our sensitivity to the horror of breaches of human rights in general.

Fortunately, most of us don’t experience breaches of our human rights in our everyday lives and, consequently, we don’t personally identify with many of these breaches, much as we might abhor them. But because pain is a universal human experience which we all want to avoid, wrongful failure to manage it is one of the rare breaches of human rights with which we can all personally identify and, as a result, better understand what breaches of human rights, in general, feel like. That is a lesson we should all heed carefully.

Ethics Informing Law: Governing Reproductive Technologies

Governance of assisted human reproductive technologies (ARTs) is another context in which both ethics and law have important roles to play and, as with obligations to provide pain management, it can make a difference to our decisions about the use of ARTs whether we consider the law first and ethics second or vice versa. It is also a context in which the language of human rights can function as a bridge between ethics and law. And it is an area that gives rise to situations in which we need to consider the ethics of our decisions at levels other than just the individual one, the cumulative impact of decisions by individuals, and what the law that governs these decisions should be. Each aspect will be discussed in turn.

Child-Centered Decision-Making

Ethics requires that decisions about the development and use of reproductive technologies must be primarily child centered, not adult centered as they most often are at present. Indeed, the law, itself, can promote adult-centered decision-making in this context, for instance, when it is interpreted to require that in order to avoid discrimination against adults, or to respect their rights to autonomy and self-determination or privacy, access to these technologies or particular uses of them that are not in the “best interests” of the resulting children must be allowed. This can give rise to ethically questionable outcomes such as creating children who, intentionally, are unable to trace their biological parents and other family members, or with three genetic parents, or a single parent, or two same-sex ones.

On the other hand, the law could also help to incorporate ethics into judicial decisions. For instance, the extent to which the courts view legal instruments that enact constitutional rights, such as the US or South African Bill of Rights or the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Being Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982), as a legal articulation and embedding of fundamental ethical norms and principles in a country’s constitution could affect the extent to which judges are willing to interpret constitutional rights so as to achieve ethical outcomes. American legal philosopher the late Ronald Dworkin calls such an approach to interpretation of a country’s constitution a “moral reading” of these laws, which has the effect of incorporating ethics into the law they promulgate.

Ethical Impact Of Legal Charters Of Rights

The more a charter of constitutional rights is seen by judges as intended to ensure that state actions are ethical, not just legal, the more likely it is that its provisions will be interpreted by courts in a way that incorporates ethics into their judgments in the interests of ensuring justice.

In the same vein, it should come as no surprise that such constitutional bills or charters are being enlisted by litigants, whose perceptions are that their claims have a strong ethical component, to promote their claims.

It was mentioned earlier that in the 1970s there was a realization that we could no longer simply assume that we all bought into the same shared societal values or that the law reflected, implemented, and upheld shared values and this realization gave rise to the emergence of “applied ethics” as a way to supplement the law. It can be proposed that legal instruments such as the Canadian Charter, which was enacted in 1982, or the South African Bill of Rights (1994) are yet another outcome of this same phenomenon, insofar as they resulted from seeing a need to articulate in a legal document a society’s shared values and ethics. It merits noting that, as in all statements of principle on which a wide societal consensus is sought, such charters are couched in broad and general language. Variance and disagreement enter at the level of the interpretation and application of their provisions.

One of the criticisms of seeing such instruments as legally enacted “shared ethics” is that it’s the proper function of the courts to implement the law, not ethics, and that their undertaking the latter task confuses and harms the law (Vonecky et al. 2013). But that is to forget a major historical feature of at least the courts in jurisdictions that have their origins in the British Common Law system. The Courts of Equity applied a “gloss on the common law,” when strict application of that law by the King’s common law courts caused unconscionable outcomes for unsuccessful litigants. They were the “courts of conscience” and acted in personam to prohibit victorious parties from enforcing such a judgment. Although operating in a very different way legally, constitutional charters of rights can be viewed as allowing twenty-first century judges to realize goals of the same nature.

One difference between using law and using ethics, and between judge-made law (case law) and legislation, to deal with a social or public policy issue is that an ethical analysis can take into account a much wider range of considerations than can an analysis based just on the existing law, and the same is true for politicians in enacting new legislation, as compared with judges in creating case law. Judges must find a legal basis for their decisions, but they can and do take into account the morality and ethics of deciding one way or another. Legislators can – and many people believe should – first look at the morality and ethics of the laws they could pass and then decide on what should be the content of those laws in light of the relevant ethics.

Ethics Informing Law And Social And Public Policy On Fundamental Rights

The ethics and law that should govern reproductive technologies is a very contentious area of social and public policy. For instance, should a person conceived from artificial insemination have a right to know the identity of the sperm donor? In many jurisdictions, at least until very recently, as the relevant law stood, the courts held there was no such right. But the proper question in these cases was an ethical one – is it ethically wrong to intentionally prevent any person from knowing through whom life traveled to them? There are good arguments that it is (Somerville 2011a).

There is rapidly increasing recognition internationally that intentionally making those who are adopted or donor conceived “genetic orphans,” by not giving them access to identifying information about their biological parents, is ethically wrong and ought to be legally prohibited. Assuming, for the sake of exploring the issue, that gamete donation is ethically acceptable (which is debatable in the eyes of some, including a growing number of donor offspring), then donor anonymity is wrong because people born from gamete donation need to know their medical histories for health reasons and their social histories in order to properly form their sense of identity.

Those opposing the prohibition of egg and sperm donor anonymity include the Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) industry (the “fertility industry”), and groups claiming to represent would-be parents, who fear that ending anonymity will lead to a drop in the number of donors and, thereby, limit their ability to have a child. Although, the UK, which banned donor anonymity in 2005, at first saw an increase in the number of donors that has now changed dramatically to a severe shortage whether we believe that is a good or bad outcome depends on how we view the ethics of artificial insemination by donors.

The issues raised in such social-ethical-legal value cases can be as much about the proper interaction of ethics and law in relation to forming social and public policy, and about the legitimate respective roles of the courts and legislatures with respect to that task, as they are about the issue that is the immediate focus of a case which involves a legal challenge, for instance, to gamete donor anonymity.

Other situations where the law and ethics interact and the legitimate respective roles of the courts and legislatures are brought into question include governance of prostitution, allowing clean-needle exchanges for people with drug addiction, legalizing marijuana, and so on. Depending upon whether one gives priority to “use reduction” or “harm reduction” in dealing with such situations, what is indicated as ethical or unethical and, therefore, should arguably be legal or illegal can be quite different.

Difficulties arise when courts disagree with legislatures with respect to how such situations should be handled and interpret the law in such a way that the court overrides a government’s policy decision. This can be criticized as the court wrongfully interfering in the exercise of executive discretion and introducing uncertainty into the application of the law and as opening up possible legal challenges to a wide range of executive decision-making and, perhaps, a wider range of bases, such as social and economic considerations, on which courts may overrule legislation. It can also be criticized by some as bad ethics. Just because a court considers ethics doesn’t mean what it decides is necessarily ethically correct. And, as we know, we don’t all agree on ethics. On the other hand, it can be seen as a court using the law in a legally complex and sophisticated way to reach an ethically acceptable outcome, when the law is used by a legislature in a manner that prevents that from happening (2011b).

Human Rights Bridging Ethics And Law To Implement Child-Centered Assisted Reproduction Decision-Making

It was previously discussed how using the language of people having a human right to have reasonable access to pain management helped to make such access a reality. More recently, the argument that a human right to be born from natural human biological origins is necessary and should be recognized (Somerville 2011a). This means that in passing laws to govern the use of reproductive technologies, we should work from a basic presumption that, ethically, children have an absolute right to be conceived from an untampered with ovum from one, identified, living, adult woman and an untampered-with sperm from one, identified, living, adult man. This, it can be proposed, is the most fundamental human right of all. In the past, we did not need to contemplate recognizing a right to come into being from natural human origins, because there was no possibility of coming into being in any other way. That, of course, is no longer true, which is the reason we need such a law based on deep ethical analysis.

It can also be proposed that children have valid claims, if at all possible, to be reared by their own biological parents within their natural family, unless an exception can be justified as in the “best interests” of a particular child, as in adoption, and to have both a mother and a father.

And society should not be complicit in intentionally depriving children of any of these rights. Therefore, the ethics of deliberately creating any situation that is otherwise must be considered, and this is an important context in which using the language of human rights can help to ensure that, as it should, ethics informs the law.

The proposed approach applies the ethical principle of acting to favor the most vulnerable, most in need, weakest persons when claims or rights are in conflict, as, for example, in same-sex marriage, where the claims of adults to found a family and children’s rights regarding their coming into existence and the family structure in which they are reared conflict. Ethics requires favoring children, and the law should reflect that.

Such proposals have been the source of enormous controversy and conflict, especially with advocates of same-sex marriage who claim to deny same-sex marriage is wrongful discrimination (Somerville 2013). Marriage is a compound right – the right to marry and to found a family. Giving same-sex couples the right to found a family necessarily abrogates children’s human rights with respect to their biological origins and family structure, and the dangers of that abrogation are amplified by reprogenetic techno science. But same-sex civil unions do not raise this problem, because they do not entail the right to found a family. Therefore, in contrast to same-sex marriage, legally recognizing civil unions does not create a conflict between ethics and law.

Why Ethics In Medicine And Science Matter More Generally, Especially To The Law

What our shared societal values should be is currently a source of conflict in North America – some call it “culture wars”– and medicine, medical science, and healthcare, collectively, are the forum in which many of the public square debates, which will determine the values that govern us as a society, are taking place (Somerville 2015). The interaction of law and bioethics is central to these debates.

Many of the issues at the intersections of science, medicine, ethics, and law involve some of our most important individual and collective social-ethical-legal values, such as respect for life. Unprecedented medical-scientific developments face us with sociotechnical value issues no humans before us have ever had to address and form, as a collective, the most prominent and important context for foundational value formation in society. That means what we decide with respect to the values that are honored or breached in this context – which values we choose to respect, create, or destroy – matters well beyond that context. In short, ethics in medicine, medical science, and healthcare matter with respect to our societal values, and it’s the role of law to uphold our most important shared values, so ethics in these areas matters to law.

There has been an exponential increase in the power of medical science and its practitioners. In the past, all a physician could do was hold a person’s hand, wipe their fevered brow, and give them an aspirin or narcotic. Today medical scientists can redesign life itself. With such powers come enormous responsibilities, and not just toward present generations but also to future ones. It is the privilege and responsibility of bioethics and law, acting together, to ensure we fulfill those responsibilities.

Both ethics and law need to uphold the value of respect for human life, in general, and for each individual human life. We can all agree on that, but where we disagree is whether, for instance, euthanasia breaches the required respect. People who reject euthanasia believe that intentionally killing another person, other than to save human life as, for example, in justified self-defense, does so, no matter how compassionate the motives of those carrying out these interventions.

The euthanasia debate can also help us to see the kinds of questions we need to ask when deciding on issues in medicine that will affect socialethical-legal values. They include exploring our obligations to future generations to hold not only our physical world but also our metaphysical world – our shared values, attitudes, principles, beliefs, stories, and so on – on trust for them. They also require taking into account the impact of our decisions not just on individuals but also on institutions, in particular, law and medicine; on our society, as a whole, especially its values; and, in our twenty-first century world, on our global reality. In short, we need comprehensive and sophisticated ethical and legal analysis at all levels – the micro (individual), meso (institutional), macro (societal), and mega (global) levels – and in the interfaces among these levels.

Conclusion

The new science has opened up, and will continue to open up, unprecedented powers, and we need bioethics to help us to answer questions such as what those powers could mean for individuals and societies and what limits, if any, the law should place on their use. This science faces us with questions that go to the very essence of what it means to be human, that no humans before us have ever faced. We must constantly ask ourselves, especially as bioethicists, jurists, and lawyers, what does acting ethically, wisely, and courageously with respect to these immense powers require of us in terms of the laws that we choose to govern them.

Ethics must inform our choices; science, ethics, and law must march forward together. Ethics is not only necessary but also beneficial to law, and law needs to march with it as an equal partner and not be in the rear and limping. Ethics can function as “first aid” for law enabling it to achieve that equality, especially in novel situations where the law is most likely to have difficulty keeping up with ethics.

Bibliography :

- Boussard, H. (2005). An ambiguous relationship between ethics and law: Study of the future declaration on universal norms on bioethics. In M.H. Sanati M (Ed.), Proceedings of the international congress of bioethics Tehran (pp.3–16). Iran, 26–28 Mar.

- French, R. (2003). Ethics at the beginning and ending of life. University of Notre Dame Australia Law Review, 5, 1–13.

- Human Rights Watch (2010). Needless pain: Government failure to provide palliative care for children in Kenya. See at http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2010/09/02/kenya-provide-treatment-children-pain

- Somerville, M. (2000). The ethical canary: Science, society and the human spirit. Toronto: Viking/Penguin; McGill Queen’s University Press (US edition), Montreal.

- Somerville, M. (2006). The ethical imagination: Journeys of the human spirit. Toronto: House of Anansi Press; (McGill Queen’s University Press (US edition), Montreal, 2009).

- Somerville, M. (2011a). Children’s human rights to natural biological origins and family structure. International Journal of the Jurisprudence of the Family, 1, 35–54.

- Somerville, M. (2011b, November 14) Is the Charter ‘applied ethics’ in law’s clothing?. Globe and Mail, A11.

- Somerville, M. (2013). “Brave new ethicists”: A cautionary tale. In N. Wiseman (Ed.), The public intellectual in Canada (pp. 212–232). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Voneky, S., Beylage-Haarmann, B., Holfelmeier, A., AnnaKatharina, H., (Eds.) (2013). Ethik und RechtDie Ethisierung des Rechts (Ethics and Law – The Ethicalization of Law). Conference proceedings, Springer/ Heidelberg/New York/Dordrecht/London, pp. 456.

- Boussard, H. (2005). An ambiguous relationship between ethics and law: Study of the future declaration on universal norms on bioethics. In M.H. Sanati M (Ed.), Proceedings of the international congress of bioethics Tehran (pp. 3–16). Iran, 26–28 Mar.

- French, R. (2003). Ethics at the beginning and ending of life. University of Notre Dame Australia Law Review, 5, 1–13.

- Somerville, M. (2006). The ethical imagination: Journeys of the human spirit. Toronto: House of Anansi Press; (McGill Queen’s University Press (US edition), Montreal, 2009).

- Somerville, M. (2015). Bird on an ethics wire: Battles about values in the culture waves; Montreal, McGillQueen’s University Press.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.