This sample Lawful Killings Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Homicide is frequently used as an indicator of violence. Its statistical superiority originates from the seriousness of this crime and from a broad availability of relevant data from law enforcement and criminal justice sources. Definitions of homicide for statistical purposes tend to focus on the intentionality and premeditation of death inflicted on a person by another person and exclude unintentional acts (non-culpable – manslaughter). Nevertheless, definitions of homicide across countries show marked differences, depending on penal codes and what is considered unlawful. Indeed, different cultures tend to criminalize different acts and behaviors.

A cross-country comparison of data based on “homicide,” therefore, should take into account that the indicator includes the elements which are criminalized in each country and may exclude others, which are not.

Behaviors defined in this research paper as “lawful killings” are acts with lethal consequences which are tolerated by some cultures and therefore do not appear in some homicide statistics. This is the case with “honor” killings, which are not criminalized in several countries.

The term “lawful killings” is used throughout the paper to indicate many different types of killings which in some contexts are considered “justified,” or less serious from a legal point of view than plain killings. This may happen because of cultural, ethical, political, or legal reasons. Depending on countries and cultures, this could be the case with any of the following: killing in self-defense; killing in revenge or retaliation; killing as a result of provocation; killing to eliminate the pains of incurable patients; killing to defend the “honor” of a person or a family. In some cases, States take in their hands the authority to kill to defend the public order (legal interventions) or to punish someone for having killed someone else (death penalty).

This research paper focuses on some specific forms of killings, namely, “honor” killings, dowry deaths, killing of persons accused of witchcraft, and mob killings, and how they relate with homicide concepts and categories. The current debate highlights two sides of the problem: on the one hand, in some countries/contexts these acts still fail to be recognized as forms of violence, sometimes even as crimes, depending on specific traditions and beliefs. Perpetrators of these killings frequently get away with committing these crimes, or enjoy more lenient investigations and sentences. On the other hand, in the countries where these killings are part of the homicide category, the seriousness of these acts may be insufficiently emphasized, and some advocate for perpetrators to be subject to sanctions harsher than those inflicted for homicides.

The paper also considers some examples of data collection or specific studies aimed at capturing relevant data to measure the extent of these phenomena.

What Is In A Label: “Homicide,” Criminalization, Culture, And Human Rights

Criminalization

The United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Systems (UNCTS), through which UN Member States exchange crime and criminal justice statistical information, defines homicide as “unlawful death inflicted on a person by another person,” which could be intentional or not.

What is considered “unlawful” depends on the definition of homicide in domestic criminal law and procedure, as well as the specific legal classification of homicide in each country. The degree of “unlawfulness” and the type of sanction foreseen for specific forms of killing vary across societies “to the extent to which different countries deem that a killing could be classified as such” (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2011, p. 10).

According to Waters (2007, pp. xiii–xiv), “a murder is a social act that involves not only killing, but also judgment and evaluation by society at large” but, still, “[e]ach society has a process through which killings are described as legal justifiable homicide, illegal unjustified homicide (i.e. murder), or just plain killings. The process varies not only with a technical or legal capacity to assign blame but also with the capacity of a particular society to respond in a manner it defines as decisive and appropriate.” The process of defining a particular killing as “unlawful” involves the social context where the act is committed as well as the traditional and cultural codes of the victim and the perpetrator. Some killings may be considered as “lawful,” mitigating circumstances invoked and, in some cases, impunity granted to the perpetrators, because the society at large does not consider they have committed any illegal acts. It can therefore happen that killings which are criminalized in some countries may not be in others. Boundaries for such considerations are represented by the cultural and sociological perception of specific issues such as honor, status distinctions, culpability, innocence and blame, as well as the state’s approach to legitimate use of force.

In some societies, perpetrators of killings in the name of “honor” or “morality” still get reduced penalties and/or may be exculpated. This happens because the killing is “publicly justified” according “to a social order claimed to require the preservation of a concept of honor vested in male (family and/or conjugal) control over woman” (Welchman and Hossain 2006, p. 4). As sustained by Wolfgang and Ferracuti’s “subculture of violence theory,” within some specific ethnic groups and when the values of “honor” and “morality” are strongly perceived and shared in the society, one’s capacity for violence may not only be admired but also perceived as an indispensable trait of personality.

Culture

The ecological approach to human development has been applied to criminology to explain the roots of violent crimes across different societies. It highlights the influence of community contexts in which social relationships are embedded and of the larger societal factors, such as cultural norms and attitudes, in explaining the level and dynamics of some specific forms of lethal violence.

Following this approach, homicide can be seen as a social and cultural construct in which the level of “seriousness” and “unlawfulness” can vary not only across different countries but also across different communities within the same country. Because of the way countries are composed and as a result of migration processes, most countries include a variety of ethnic and religious groups, even where a majority of the population shares the same culture.

The influence of culture is crucial to determine which behaviors are criminalized and which are not, reflecting majoritarian cultural values at the time when legislation is passed. Changes in culture and social acceptance of specific values could influence the consideration of specific behaviors as unlawful or not.

Analysis of the World Values Survey (WVS) results (a worldwide investigation of sociocultural and political change, conducted by a network of social scientists at leading universities on national samples of at least 1,000 people in 97 societies in all 6 continents) reveals that many of the basic cultural values closely relate with each other and can be grouped along two major cross-cultural dimensions, namely, one going from “Traditional” to “Secular-rational” values and one from “Survival” to “Self-expression” values.

Moving from “Traditional” to “Secularrational” values reflects the shift from traditional religious values to secular-rational attitudes.

Moving from “Survival” values to “Self-expression” reflects the shift of individual focus from personal and economic security to personal self-expression and quality of life.

Self-expression values, which focus on subjective well-being, freedom to express oneself, and quality of life, may give high priority to environmental protection, promotion of gender equality, tolerance of different characteristics and behaviors (such as migrants, foreigners, gays, and lesbians), and rising demands for participation in decision-making in economic and political life. Moreover, societies that rank high on self-expression values also tend to rank high on interpersonal trust. These types of society may therefore be much less tolerant with regard to any form of deprivation of life and crimes against the individual. Traditional and survival values stress the importance of parent–child ties and traditional family values and reject divorce, abortion, euthanasia, and suicide.

Many of these factors could have a strong influence on some types of lethal violence perpetrated within families. Societies and communities based on strong traditional values could also show higher levels of tolerance with regard to specific types of killings committed in the name of the family’s respect and honor (Luopa 2010).

Nevertheless, as a result of globalization, there may be no clear-cut attribution of specific cultural values to specific countries. Therefore, different communities based on very different cultural values and norms may coexist within the same country.

Some types of killings could be “justified,” or even considered “necessary” under specific circumstances, by some types of cultural values. More in-depth knowledge of causes and reasons for such considerations may allow preventing and contrasting these forms of lethal violence by focusing on their cultural roots.

Citizens of Western countries still tend to believe that “honor crimes” are a prerogative of Asian and African cultures, while this phenomenon is visibly increasing also in Europe (particularly in France, Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, UK, and Turkey) and in the US (Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly 2009, p. 6; Chesler 2010, p. 3). For example, a recent study found a correlation between higher homicide rates observed in the US South and “culture of honor” as a heritage of herding carried out by early settlers, indicating that “the Southern propensity for homicide stems largely from the cultural background of the early Southern settlers alone and, in any case, is fully accounted for by the cultural background of early settlers together with current economic conditions and demographic characteristics” (Grosjean 2010, p. 20).

Indeed “honor” crimes disappeared from criminal codes in Europe (especially Western Europe) and in the US a long time ago and events of similar nature may be currently registered under the label of “domestic violence.” However, their characteristics, motivations, and evolution are completely different. For example, “unlikely domestic violence, honor killings often involve multiple family members as perpetrators” (Chesler 2010, p. 3).

A proper assessment of the extent and distribution of “lawful” killings across different countries is necessary in order to properly prevent, contrast, and sanction them. In this respect, proper recognition of different cultural settings and understanding of how such data would be contributing in terms of policy relevance are necessary. For example, the proposal for an international classification of crime for statistical purposes currently discussed at the UN level considers the categories of infanticide and euthanasia separately as specific types of intentional homicide (UNODC/UNECE Task Force on Crime Classification 2011, p. 25).

Human Rights Perspective

It is important to place the present subject within the human rights law discourse. Human rights are universal and belong to every human being in every society. Therefore, human rights are generally regarded as neutral.

The issue of homicide has found its corollary in the discussion on “right to life.” For human rights law, it is taken for granted that States are not only required to refrain from directly violating the right to life, but are also obliged to take positive measures to protect the individual from abuses committed by other individuals, that is to prevent such crimes and prosecute and punish the perpetrators. If initially, the right to life was envisaged as a protection from direct violations by the state, it has developed to impose on states obligations of prevention in relation to acts perpetrated by private persons.

Under human rights law, impunity for a homicide may constitute a violation of the right to life. Within the international human rights law system, only the regional legal framework, namely, the European Convention on Human Rights, specifies in a detailed way limitations on the right to life. In particular, it allows limitations of a right to life under certain conditions resulting from the use of force among others in self-defense from unlawful violence, “which is no more than absolutely necessary” (Article 2). Thus, domestic legal order may allow self-defense under conditions specified by the relevant human rights treaty. In reality, however, the debate on self-defense is much more complex.

Human rights consequences of the types of killings discussed here do not concern exclusively the right to life. Indeed, many of them involve different forms of discrimination, particularly on the basis of gender and age. A concrete case in point is “honor” killing, where discrimination can be dissected in the fact that laws applicable to this crime envisage an unequal treatment of men and women. Other potential human rights issues at stake may include nondiscrimination and equality as well as violations related to violence against women.

In practice a number of measures have been undertaken to address these issues. The human rights Treaty Bodies and Special Procedures of the United Nation’s Human Rights Council have accumulated a considerable practice generally on the right to life but also as a result of the work of the treaty bodies in the context of protection of women and children against violence. General Assembly Resolution 59/165 of 10 February 2005 recalls the obligation of all States to use legislation to prevent and combat crimes in the name of honor with a view to their elimination. It also reminds the duty of states to investigate, prosecute effectively, and document cases of crimes against women and girls committed in the name of honor and punish perpetrators. Similar recommendations have been put forward in relation to the phenomenon of witchcraft. It is clear that human rights consequences of the “lawful killings” are expansive. International legal framework tends to prohibit all the practices falling under this classification by virtue of guarantees of the right to life and nondiscrimination both at universal and regional levels. States are therefore saddled with a duty to criminalize homicide and homicide-related practices.

Measuring The Extent Of “Lawful Killings”

Measuring “lawful killings” requires broadening the perspective beyond criminalization to include the social and cultural aspects related to crime definition and reporting/recording behaviors and procedures. Available homicide statistics may be an adequate tool to measure the incidence of “lawful killings,” depending on two levels of challenges to be considered. The first level is related to the general difficulty in comparing crime statistics across countries. The quality of statistics depends indeed on the efficiency of national reporting systems, so that discrepancies in homicide rates across countries may originate from different degrees of efficiency and/or from national-level underreporting or nonreporting issues rather than real differences in violence incidence. Moreover, homicide cases are recorded according to counting rules for statistical classification by using different units (persons, cases, victims) and time of registration (at the time of reporting/discovery of a case, at different point in time during investigation, etc.) so that direct cross-national comparison should be pondered over methodological limitations to avoid misleading interpretations of data.

The second level of challenges depends on operative definitions of crime for data collection and how they affect the classification of homicide data for statistical purposes. The general heading “homicide” may cover substantial differences in the patterns of violence. In general, definitions for unlawful killings vary depending on the involvement of legal concepts related to the perpetrator, such as motivation, involvement, responsibility, and planning. A recent study on European homicide research (Liem and Pridemore 2012) has identified two main elements in national definitions of homicide: intent and premeditation. The role of both intent and premeditation (and/or other aggravating circumstances) determines the criteria for statistical classification of unlawful killings. Differences in homicide statistics across countries, thus, depend also on whether premeditation, intent, and aggravating circumstances are defined by autonomous provisions (Liem and Pridemore 2012, p. 10).

Even when the characteristics of homicide appear clearly defined by criminal law, there are cases that may fit the definition but “there is less consensus on whether or not they should be comprised under the label homicide” (Liem and Pridemore 2012, p. 12). This refers in particular to the categories of attempted homicide, assault leading to death, euthanasia, and infanticide, which in some countries are not considered elements of homicide. Analysis carried out by the European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics about the compliance of European countries to the operative definition of homicide (“intentional killing of a person; where possible it should include assault leading to death, euthanasia, infanticide, attempts; but exclude assistance in suicide”) based on inclusion/exclusion of such elements in national definitions of homicide demonstrates that only 13 countries out of 36 fully comply with the definition (Aebi et al. 2010, pp. 343–344). Liem and Pridemore (2012, p. 16) have reviewed elements included in national statistics on homicide in 34 countries also in relation to causing death by dangerous driving (which is included by 13), justified killing (10 countries), and nonintentional killings (17 countries). Altogether these findings help in understanding the impact of cross-national differences in defining homicide on the comparison of homicide rates across countries.

Consensus on what is to be considered homicide and what may be excluded, thus “excusable,” depends on a wide range of cultural influences, which may go back to ancient customs incorporated in many countries. This includes a shared acceptance of which circumstances can be considered as mitigating the offense, and the concept of provocation.

While there may be a large consensus in considering mitigating circumstances for killings that occur on duty or to defend life, some cultures may consider legitimate or justifiable the killing of an unfaithful wife or of a child suspected of witchcraft. This generates several types of “lawful killings,” for example, mob killings, witchcraft/ritual killings, “honor” killings, and dowry killings, for which some patchy statistics are available.

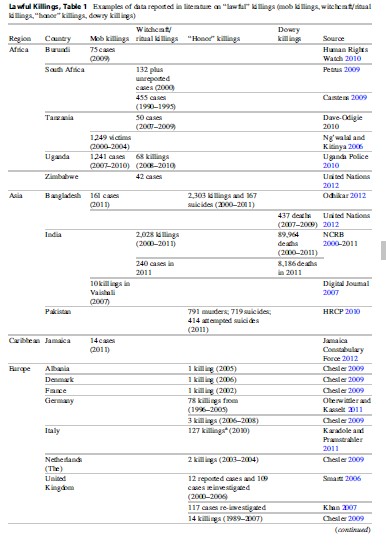

Table 1 provides some examples of available data and related sources on selected types of “lawful killings”, without the ambition to provide a complete picture of their incidence and distribution. Data presented in the table are commented in the relevant sections below.

Mob Killings

The UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial killings and summary or arbitrary executions has described mob killings as “those undertaken by individuals or groups who take the law into their own hands. They are killings carried out in violation of the law by private individuals with the purported aim of crime control, or the control of perceived deviant or immoral behavior. Specific incidents of vigilante killings can most usefully be categorized along various axes – such as spontaneity, organization, and level of State involvement – and can be considered in relation to various characteristics – including the precise motivation for the killing, the identity of the victim and the identity of perpetrators” (United Nations 2009, para 51).

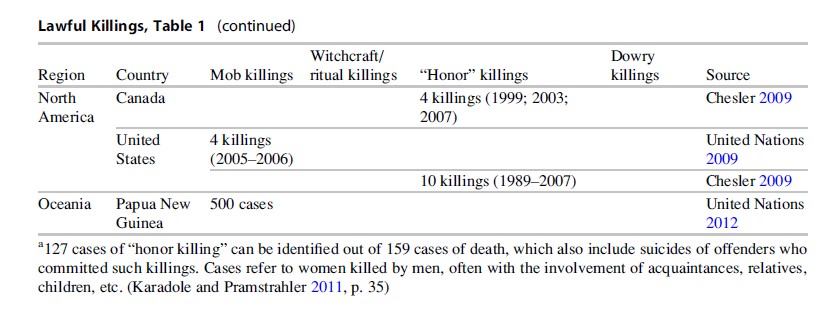

These forms of killing have been reported from all around the world to the extent that they do not represent an issue limited to any particular region but they should be considered a potential concern for all States (the report refers to cases recorded in Australia, Brazil, Benin, Burundi, Cambodia, the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Guatemala, Guinea, Haiti, Hungary, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kenya, Liberia, Mexico, Nepal, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda). Victims are most frequently young males, who are often suspected of having committed theft, robbery, or murder, or being accused of witchcraft. The modalities of these killings vary from stoning to burning to lynching by the use of canes, machetes, or any type of weapon (Ng’walal and Kitinya 2006). For example, the Uganda Police provides statistics for death by mob action. Data refer to the number of investigations. Since each episode could involve more than a victim, the actual number of persons killed is probably largely underestimated (see Table 2). The increase observed in 2011 was commented by the police as “attributed to thefts, robbery, suspected witchcraft, and dissatisfaction with delayed/omission of justice” (Uganda Police Force 2011, p. 9).

Literature suggests that mob killings are likely to occur where the judicial system is weak and affected by corruption (United Nations 2009; HRW 2010). The summary executions of suspects by angry crowds would then be a response to the limited presence of the State which is perceived as lacking or delaying proceeding against criminals, causing public distrust towards justice and law enforcement institutions. Others point to inefficacy of formal and informal dispute resolution systems and the conflict between the cultural and the legal frameworks. Witchcraft is the typical example of a behavior frequently not recognized by courts, but strongly felt by the traditional culture of society. In these cases, the lynching of alleged witches is perceived by communities as an acceptable alternative form of administration of justice.

Killing Of Witches

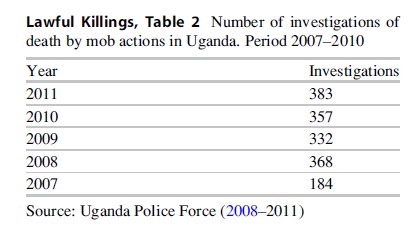

Another form of “lawful killings” related to belief systems is related to killing of persons accused of witchcraft. This practice is found mainly among tribal communities in Africa, Asia, and Pacific Islands and appears to target mainly women, elders, and children (United Nations 2012). Victims of witchcraft accusations are likely to belong to the most vulnerable positions in society: elders and people with some form of disability or unique characteristics, such as albinos, for which they are discriminated (Dave-Odigie 2010). These killings often take place in post-conflict and post-disaster settings, or regions burdened by public-health crises. These phenomena are still frequent and rooted in lack of education and opportunities for protection of the weakest elements of the society. Such killings are captured by official statistics in India; according to the NCRB, 240 cases of witchcraft killings were reported in India in 2011. Reports of witchcraft killings have almost doubled over the last decade, with sharp increases between 2004 and 2005 and again between 2010 and 2011 (see Fig. 1). Figure 1 also shows an increase in reports of dowry deaths, the characteristics of which are described below.

Available statistics on ritual killings published by the Uganda Police Force account for 29, 14, and 8 ritual killings for 2009, 2010, and 2011, respectively (Uganda Police Force 2010, 2011). According to the Uganda Police, the remarkable decline in ritual killings was achieved against some serious challenges, including that many people still believe in witchcraft and practice rituals and some quack healers demand human body parts for their rituals (Uganda Police Force 2011, p. 10). Given the above-mentioned impact of underreporting and deficiencies in the recording systems, it may be estimated that the incidence of such killings is actually higher.

The most recent Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women notes the occurrence of 42 cases of killings of women due to accusations of witchcraft in Zimbabwe and other 500 in Papua New Guinea (United Nations 2012, p. 11).

“Honor” Killings

“Honor killings can be understood as an extreme result of the combination of patriarchal dominance over women and their sexuality, rigid behavioral norms, and the importance of honor for social relations in economically and socially backward, agrarian societies” (Oberwittler and Kasselt 2011). “Honor” killings exist as a mitigating circumstance in many countries/ territories. For example, in 6 Mexican States out of 32 (Michoaca´n, Baja California Sur, Chiapas, Jalisco, Yucata´n, and Zacatecas) “femicide for honor reasons” is sanctioned with sentences between 3 days and 5 years imprisonment (Chouza 2012). The perpetrators of such killings are convinced they act to safeguard the “honor” of men and families to remedy inappropriate behaviors or shameful incidents, most frequently committed by women and girls. The reasons behind killings include adultery, the choice of a partner, seeking divorce, and also homosexuality, bisexuality, and trans-sexuality. In some cultures, when a woman is the victim of rape, this is considered to bring shame to the family and victims may be killed in the belief that this will restore the lost “honor.”

The clash between different cultural values within the same country or the adaption of some members of one specific community to the “new” cultural context could be one reason for “honor” killings. These issues have been analyzed by Chesler (2010, pp. 4–5) in her study on 230 victims of honor killings in North America, Europe, and 14 countries in the Muslim world (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, Gaza Strip, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey) between 1989 and 2009. The results of this study demonstrated that “worldwide 58 % of the victims were murdered for behaving ‘too Western’ and/or for resisting or disobeying cultural and religious expectations.” Indeed, since the process of adaptation to different cultures can be perceived as dishonorable by the victim’s family, immigrant communities seem to be vulnerable to the problem of “honor” killings to the extent that the risk of being killed in the name of “honor” is higher among immigrant communities in the “Western world” than it is in the countries those immigrants come from (Luopa 2010, p. 7).

However, there is no specific cultural or local connotation for “honor” killings. For example, a study on 78 cases in Germany showed that “in 80 % of the cases an unwanted love affair by a woman, outside or after marriage, was the main reason for the homicide, whereas a desire to live an autonomous ‘Western’ lifestyle was the only central factor in very few cases.” This study also demonstrated that “honor killings frequently occur in the context of ‘arranged marriages’, either when young women violate the norm that their partner will be chosen by the family or when married women want to escape from an unbearable relationship which is the consequence of an arranged marriage.” Moreover, two-thirds of these homicides were committed in families of Turkish or Kurds origins, by first-generation immigrants, without Germany citizenship (Oberwittler and Kasselt 2011, pp. 2–3).

A recent study shows that in Italy, 127 women were killed by an intimate partner or former partner during 2010. Of these 70 % of victims and 76 % of offenders were Italians and the motives of killings included conflict in the relationship, men’s unemployment, and “honor” (United Nations 2012, p. 8, Karadole and Pramstrahler 2011). The occurrence of “honor” killings in countries where “honor” crimes are not supposed to exist implies that these killings are likely to be recorded as domestic violence, thus limiting the knowledge on the real nature and extent of the phenomenon (see Table 1). The Council of Europe has expressed concern about the increase in the frequency of “honor” crimes and the insufficiency of adequate recording of their occurrence (Council of Europe 2003), which lead to progressive raising of awareness of the scale and the dynamics of the problem and reviewing cases (for example, a national review of nearly 120 cases of murder in the UK lead to the identification of at least 13 cases of suspected “honor” killings).

Reliable data are lacking. In 2003 the UN Population Fund estimated that approximately 5,000 women and girls are killed in “honor killings” every year in the world. According to the last report by the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, “honor killings take many forms, including direct murder; stoning; women and young girls being forced to commit suicide after public denunciations of their behavior; and women being disfigured by acid burns, leading to death” (United Nations 2012, p. 12;).

Dowry Deaths

Dowry-related killing is a practice related to religious and cultural traditions of South Asian countries; ant dowry laws have been enacted in India (1961), Pakistan (1976), Bangladesh (1980), and Nepal (2009) (United Nations 2012). Indian criminal law describes dowry deaths as follows: “where the death of a woman is caused by any burns or bodily injury or occurs otherwise than under normal circumstances within 7 years of her marriage and it is shown that soon before her death she was subjected to cruelty or harassment by her husband or any relative of her husband for, or in connection with, any demand for dowry, such death shall be called ‘dowry death’, and such husband or relative shall be deemed to have caused her death” (304b IPC). The payment of dowry for marriages was abolished in 1961 with the Dowry Prohibition Act; however, the incidence of killings related to dowry is still problematic (see Table 2 and Fig. 1). According to the statistics provided by the NCRB, dowry-related killings have increased by 23% over the last decade (2000–2011) and dowry represents the fifth motive for murder in India (see Fig. 1 and Table 2). According to official statistics, dowry is the fifth cause of murder. The distribution of these types of killings within India appears patchy as no cases have been reported in 10 regions, while dowry is the main motive for killings in Orissa and West Bengal, accounting for, respectively, 48 and 45 % of identified cases for which a cause was identified in 2011. Despite attempts towards criminalization of “honor” and dowry-related crimes, and removing the right to pledge for mitigating circumstances, these killings are still very frequently considered as “lawful.” States responses to these forms of violence often fail in eradicating traditional customs, which frequently also involve police officers and judges who might use a discriminatory and gender-biased approach in applying the law (Luopa 2010).

Conclusions

In conclusion, “lawful” killings represent a hidden form of lethal violence, supported by some consensus and even by law in some cultures, which mostly affects women and other vulnerable groups in the society. A large portion of this violence goes undocumented, a part is recorded but fails to prominently feature in official statistics, which struggle in describing the extent of such phenomena. Beyond violence caused by the hand of husbands to wives, parents to daughters, relatives and community members to persons who are perceived as “different” or having infringed some (frequently unwritten) community laws, there are also many cases of suicides of women who are unable to find a way out from the psychological and physical abuses suffered.

Capturing the extent of these forms of violence faces both technical and cultural obstacles, as regards general limitations of comparative crime statistics and different understanding on what is to be considered “unlawful” death. In order to enhance the understanding of lethal violence patterns, more efforts should be paid in the recording and classification of the circumstances related to killings, such as, for example, a detailed description of the act/event, the alleged motives for the act, the characteristics of the perpetrator and the victim. The accuracy in the collection of this information is crucial in terms of analysis and policy making at both national and international levels.

Indeed, as stated by the UNODC/UNECE Task Force on Crime Classification (2011, p. 12), “a crime classification at international level, under the principle of exhaustiveness, should cover all possible acts or events that could carry criminal responsibility and sanctions anywhere in the world.” Therefore, it would be challenging to understand how to provide an unique interpretation of “honor” killings, dowry deaths, or killing of witches, which in some parts of the world do not imply criminal responsibility and do not carry sanctions.

Bibliography:

- Aebi M et al (2010) European sourcebook of crime and criminal justice statistics – 2010 (4th edn). Boom Juridische uitgevers, Den Haag. Onderzoek en beleid series, no. 241, Ministry of Justice, Research and Documentation Centre (WODC). Accessed on 27 July 2012

- Carstens Pieter A (2009) The cultural defence in criminal law: South African perspectives. In: Foublets MC, Renteln AD (eds) Multicultural jurisprudence: comparative perspectives in the cultural defence. Hart, Oxford

- Chesler P (2009) Are honor killings simply domestic violence? Middle East Quart 16(2):61–69

- Chesler P (2010) Worldwide trends in honour killings. Middle East Quart Spring 2010;17(2):3–11

- Chouza P (2012) Feminicidio “por honor”. El Pais. http://sociedad.elpais.com/sociedad/2012/03/05/actualidad/1330981386_402961.html

- Council of Europe (2003) So-called “honour crimes”. Report, Committee on Equal Opportunities for Women and Men. http://assembly.coe.int/Documents/WorkingDocs/doc03/edoc9720.htm

- Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly (2009) Doc. 1193 The urgent need to combat so-called “honour crimes”, 8 June 2009

- Dave-Odigie CP (2010) Albino killings in Tanzania: implications for security. Peace Stud J 3(1):69–75

- Digital Journal (2007) Another mob killing reported from India’s Bihar state. http://www.digitaljournal.com/ article/231650#ixzz1qENu9NNS

- Grosjean P (2010) A history of violence: testing the “culture of honor” in the US South. Mimeo, University of San Francisco. http://www.feem.it/userfiles/attach/201011815184441_Grosjean_paper.pdf

- Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) (2010) Annual Report. State of Human rights in 2010. http://www.hrcp-web.org/Publications/AR2010.pdf

- Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2010) Mob justice in Burundi. Official Complicity and Impunity, United States

- Jamaica Constabulary Force (JCF) (2012) Annual major crime statistics review

- Karadole C, Pramstrahler A.ed (2011) Femicidio. Dati e riflessioni intorno ai delitti per violenza di genere. Regione Emilia Romagna – Assessorato Promozione Politiche Sociali. http://www.casadonne.it/cms/images/ pdf/pubblicazioni/pubblicazioni/femicidio_pdf.pdf

- Khan R (2007) Honour-related violence (HRV). In: Scotland: a cross and multi-agency intervention involvement survey, Internet Journal of Criminology

- Liem MCA, Pridemore WA (2012) Handbook of European homicide research. Patterns, explanations and case studies. Springer, New York

- Luopa K (2010) State responses to honour killings. A˚ bo Akademi University. http://www.abo.fi/instut/imr/norfa/Katja%20Luopa%20killings.pdf

- NCRB (National Crime Records Bureau) (2000–2011) Crime in India. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi

- Ng’walal PM, Kitinya JN (2006) Mob justice in Tanzania: a medico-social problem. Afr Health Sci 6(1):36–38

- Oberwittler D, Kasselt J (2011) Ehrenmorde in Deutschland. Eine Untersuchung auf der Basis von Prozessakten [Honour Killings in Germany. A study based on prosecution files] (Polizei+Forschung, Bd. 42, hrsg. vom Bundeskriminalamt). Wolters Kluwer Deutschland, Koln

- Odhikar (2012) Human rights report. Odhikar Report on Bangladesh, January

- Petrus TS (2009) An anthropological study of witchcraftrelated crime in the Eastern Cape and its implications for law enforcement policy and practice. PhD dissertation, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa

- Smartt U (2006) Honour killings. Justice Peace 170(7):4–7

- Uganda Police Force (2008–2011) Annual crime and traffic/road safety report. http://www.upf.go.ug/Reports/ Annual%20Report%202008.pdf

- United Nations (2009) Report of the special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, A/64/187. http://www.extrajudicialexecutions.org/ application/media/64%20GA%20SR%20Report%20 (A_64_187).pdf

- United Nations (2012) Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Rashida Manjoo. A/HRC/20/16 http:// www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/A.HRC.20.16_En.pdf

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2011) Global study on homicide, Vienna. http://www.unodc. org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/Homicide/ Globa_study_on_homicide_2011_web.pdf

- UNODC/UNECE Task Force on Crime Classification (2011) Principles and framework for an international classification of crime for statistical purposes. Report to the Conference of European Statisticians

- Waters T (2007) When killing is a crime. Lyenn Rienner, Boulder

- Welchman L, Hossain S (2006) Honour – crimes, paradigms and violence against women. Zed Books, London

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.