This sample Plagiarism Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Abstract

Plagiarism is an ethical issue of considerable practical impact, affecting educational systems and research worldwide, but also influencing art, music, and literature. The academic discussion on plagiarism in basic education mainly concerns its frequency and explanation and potential countermeasures. Ethical aspects more often come to the fore in the discussions of plagiarism in research, particularly concerning plagiarism of text, where there is considerable disagreement. While plagiarism is frequently brought up as an important aspect of scientific misconduct in research ethical guidelines, and a variety of definitions have been offered in this context, such documents rarely reflect a deeper understanding of the concept, its relation to similar concepts, its embeddedness in specific practices, or its normative implications. More research on these issues is needed, although suggestions have been made as to how plagiarism should be understood, demarcated, explained, detected, normatively analyzed, and counteracted.

One theme with an obvious global focus concerns the cultural dependence of attitudes toward plagiarism, for instance, whether differences in perception and practice can be explained by differences in relation to authorities. An important point for the future is whether or not present practices regarding plagiarism need to be changed in order to better promote progress in research.

Introduction

Plagiarism remains a persistent problem within both education and research. In relation to the educational system, the problem of plagiarism is often described as widespread and growing. Several studies show that a majority of students plagiarize during their studies; others show percentages slightly below that. In relation to academic research, plagiarism is listed as one of the core instances of scientific misconduct and has been described as “a crime against academy,” even “academic high treason” (Bouville 2008, p. 311). But it is also acknowledged that there is a large span between different instances of plagiarism, ranging from careless accreditation to premeditated fraud.

Plagiarism constitutes a considerable part of scientific misconduct. In a study of retracted misconduct publications internationally by Stretton et al. (2012), plagiarism was the reason for retraction in 41.8 % of the cases and was on the rise. It is, however, unclear whether the increase in detected cases of plagiarism is best explained by an increase in plagiarism or by improved detection.

Several studies measure the frequency of plagiarism among researchers. The numbers vary considerably with location, respondents, and methods of investigation. For instance, in a paper on scientific misconduct among researchers in the USA, less than 2 % of the respondents claimed to have been engaged in plagiarism during the last 3 years. When applying plagiarism detection software, a Chinese journal found that 31 % of examined papers contained plagiarism. In a questionnaire-based article on Nigerian researchers, 9.2 % of the respondents reported having been involved in plagiarism (Helgesson and Eriksson 2015; Okonta and Rossouw 2013). International large-scale studies on the frequency of plagiarism are lacking, among both students and researchers.

There is a notable tension between different perceptions of plagiarism and no full agreement on its normative relevance.

Definition

Journal editorials tend to discuss plagiarism as if there is broad agreement on both its meaning and normative relevance, but several authors acknowledge that there is disagreement and ambiguity in its present uses, across as well as within disciplines (Bouville 2008; Helgesson and Eriksson 2015; Sun 2013; Wager 2014). Indeed, a wide variety of definitions and measures of plagiarism have been suggested.

A few examples of proposed definitions illustrate some of the differences: In the Longman Contemporary English Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, plagiarism is defined as “when someone uses another person’s words, ideas, or work and pretends they are their own.” The Merriam Webster Online Dictionary explains that to plagiarize means “to steal and pass off (the ideas or words of another) as one’s own” and “to commit literary theft.” The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity defines plagiarism as “the appropriation of other people’s material without giving proper credit.” Other kinds of definitions specify a minimum length of word strings, used from another source without proper referencing, as a line of demarcation for what is and is not to be counted as plagiarism (Bouville 2008; Sun 2013).

On a common view, plagiarism involves theft (Helgesson and Eriksson 2015; Wager 2014). However, it has been shown that this is not necessarily the case and that theft therefore should not be part of the definition (Bruton 2014; Helgesson and Eriksson 2015). First, while stolen property remains stolen even if one accredits the source, plagiarism is no longer an issue when the source is appropriately recognized (referenced – and quoted, if relevant). Second, an author may willingly give a paper away while encouraging the recipient to publish it as his/her own. If he/she did that, then it would not be theft, but it would still be plagiarism, since the recipient would present another’s results or text as his/her own. One can also plagiarize text that is not owned by anyone, which would not involve theft (if it is not owned, it cannot be stolen). As noted by Anderson and Steneck (2011), while plagiarism has two components, (1) taking (in the sense of using) results/ words/ideas from someone else and (2) presenting it as one’s own, it is the second part that is characteristic of plagiarism.

Must ill-referenced copying be intentional in order to be plagiarism? Some of the definitions above include expressions like “pretending” and “stealing and passing off as one’s own,” which clearly indicate intention, while others do not. In the literature, there seems to be a clear majority for understanding plagiarism in a way that does not presuppose intention, and this also seems to be in accordance with ordinary usage. Thus, if large chunks of text are copied from someone else without proper Bibliography :, then it is plagiarism regardless of whether or not the person copying is intentionally misleading or is aware that he or she is doing something inappropriate (Helgesson and Eriksson 2015).

As noted above, some have suggested that plagiarism can be quantitatively determined, e.g., that if so-and-so many consecutive words are copied without proper reference, then it is plagiarism (Wager 2014). However, such a definition is difficult to defend. It would bring arbitrariness into the definition – why would copying five or six or seven or eight consecutive words be plagiarism, but not copying one word less (Bouville 2008)? More importantly, it does not catch the basic idea of plagiarism: plagiarism involves inappropriately referenced use of ideas, results, or phrases that are someone else’s. Very general statements, written by large numbers of people independently of each other, cannot reasonably be said to be anyone’s – “they belong to a common pool of expressions and sentences to which no one has an intellectual claim” (Helgesson and Eriksson 2015, p. 96). Plagiarism presupposes originality. In order to determine whether or not a string of words is plagiarized, it is not enough that you find that string in some other source. You have to determine whether that string of words commonly occurs in texts or is unique to one source (or, possibly, a few sources). Thus, a very short word string can be subject to plagiarism, while a considerably longer one may not. However, the larger the chunk of text that is identical to one found in another source, the more likely it is that it is an instance of plagiarism: “The longer passage may uniquely be attributed to a particular author, even though the individual sentences cannot” (Helgesson and Eriksson 2015, p. 97).

Despite the variation in definitions of plagiarism, many definitions proposed by major research ethical guidelines and leading organizations nevertheless are quite similar, in the style of the definition applied by the US National Science Foundation (2012, p. 237): “the appropriation of another person’s ideas, processes, results or words without giving appropriate credit.” A common variation is exemplified by Anderson and Steneck (2011, p. 90): “Plagiarism is the presentation of another person’s words, work, or ideas as one’s own.” If others’ work is presented as your own, then you do not give them appropriate credit, which means that these two kinds of definition mainly identify the same cases as cases of plagiarism.

It follows from these definitions that many aspects that are occasionally brought up in investigations on plagiarism are in fact irrelevant for determining whether or not it is a case of plagiarism, such as who is plagiarized (e.g., an established researcher or a master student), what is plagiarized (e.g., a published article, a nonacademic report, an unpublished student essay, or an oral presentation), the intended audience/purpose (such as whether it is the same or different for the plagiarizing work as for the original work), and the scientific merit value (i.e., what merit plagiarizers can gain from their plagiarism) (Helgesson and Eriksson 2015).

Related Concepts

Some concepts are frequently brought up in relation to plagiarism because they constitute plagiarism, manifest similarities, or are conflated with it. One of them is self-plagiarism. Many of those inclined to use the term regard self-plagiarism to be a kind of plagiarism. Indeed there are similarities. Both plagiarism and so-called self-plagiarism involve overlapping publication. Previous results, or text, in whole or in part, are reused in a way that gives the impression that what is presented is novel. Plagiarizers and self-plagiarizers alike therefore also tend to obtain scientific recognition (again) for something that deserves credit only once, and this is arguably accomplished in both cases by being deceptive and dishonest or at least by being unintentionally misleading (Bruton 2014; Helgesson and Eriksson 2015). However, there are also important differences between self-plagiarism and plagiarism, the most obvious one being that plagiarizers present the outcome of others’ intellectual efforts as their own, while self-plagiarizers reuse their own material without telling that it is reused. In other words, self-plagiarism does not involve using others’ work while presenting it as one’s own, but only reuse of one’s own results or text. Therefore, it does not match standard definitions of plagiarism. This has led some to regard self-plagiarism not only as a confusing term but as an oxymoron (Bruton 2014). What is called self-plagiarism is perhaps better labeled duplicate publication when the entire research paper is published more than once without proper notification that the material is reused, while redundant publication or inappropriate recycling might be better terms for non-notified republications of selected passages (Bruton 2014; Helgesson and Eriksson 2015).

Patch-writing is quite often mentioned in articles on plagiarism, i.e., when authors take a little bit from here and a little bit from there and build a text that mainly consists of text fragments from other sources. Some regard patch-writing as a mild form of plagiarism. However, unless texts produced this way fit the plagiarism definition, they are not instances of plagiarism, but simply examples of independent and poor quality academic work.

While the standard perception of plagiarism involves an individual dishonestly obtaining undeserved scientific credit on his or her own initiative, there are instances of plagiarism where others in fact encourage the misconduct. For instance, sometimes renowned researchers are invited to be coauthors on papers to which they have made no substantial research contribution (so-called gift authorship or honorary authorship). By having a renowned name on the paper, the other authors might hope to facilitate publication in a good journal. When taken to the extreme, those who have done the research and writing up of the paper are not included as authors (ghost researching and ghostwriting), while researchers who have not been involved in the research are asked to pose as authors of the paper. Historically, this has mainly happened when pharmaceutical companies have wanted full control of the research and publication process, while wanting to give the impression that the research was carried out by independent academic researchers (Moffat and Elliot 2007). Posing as an author of a paper researched and written by others is a clear case of plagiarism. Thus, there is a strong connection between ghost-researching/ghostwriting and plagiarism. Also in cases of accepted gift authorship, where the actual researchers are all credited as coauthors of the paper, the person receiving the authorship without having contributed substantially to the paper is committing plagiarism.

Copyright is another term that relates to plagiarism, but one that is concerned with the legal right to intellectual property, such as representations of original creative work. Plagiarizing someone else’s intellectual product and infringing on someone else’s copyright are, however, two different things. For instance, you may plagiarize a text that is not protected by copyright. You may also make a copyright intrusion without plagiarizing. Plagiarism of an unpublished text is an example of the first case. Publishing a previously published illustration or graph, with proper reference but without asking the copyright owner for permission (when that is required), is an example of the latter. Furthermore, ideas that do not have a “tangible form,” i.e., are documented somehow, cannot be protected by copyright, but they can still be plagiarized (Bruton 2014; Helgesson and Eriksson 2015).

Ethical Dimensions

Plagiarism is a value-laden term – apart from a descriptive content, it has a normative flavor. By claiming that an act is an instance of plagiarism, the speaker is thereby (normally) claiming that the act is bad. Frequent suggestions as to why plagiarism is reprehensible are (1) that it involves being untruthful and deceptive – and in a subset of cases dishonest – by what it implies about the creation of the text, idea, image, etc. at hand and (2) that it involves misplacement of appropriate credit for the plagiarized intellectual product, which makes it unjust. Plagiarism may also have negative consequences: it may bring unfair advantages to the plagiarizers, such as better grades for students or a better career/more research funding for the researcher, while potentially causing harm to the plagiarized person(s), to colleagues, or to readers.

It is one thing to say that plagiarism is bad, yet another to say how bad a certain occurrence is. Not least for normative purposes, it is desirable to be able to distinguish between major and minor forms of plagiarism. Several authors have argued that the severity of plagiarism varies depending on factors like what is plagiarized and how much.

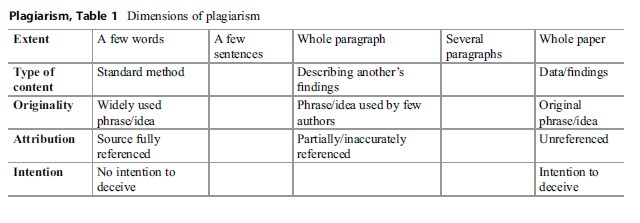

Wager (2014) has suggested a set of dimensions relevant to an evaluation of plagiarism, each with different levels of severity (Table 1). For instance, examples of major plagiarism are cases where the whole papers, important original ideas, or research results (including images containing original data) are plagiarized. It is a matter of minor plagiarism, for instance, if a few sentences have been copied from a typical background description or a description of standard methods and where the plagiarizer has provided a reference but not quotation marks.

This categorization is intended as an overview of central aspects and degrees of plagiarism. However, some of the end points of the listed dimensions do not, or do not necessarily, constitute plagiarism. Most obviously, fully and accurately referenced uses of others’ writing do not constitute plagiarism, nor do a few words or a few sentences copied from a part of a paper that does not contain anything original, but only widely used phrases. This is also the case, for instance, for non-referenced reuse of a standardized description of a common method. On the other hand, “borrowing” a few words may constitute plagiarism, even major plagiarism, if an important idea or interesting results are appropriated this way. This means that where in the “extent dimension” a case of plagiarism ends up gives an indication of its seriousness (more is often worse than less), but it is only an indication (sometimes less of something is worse than more of something else). For instance, copying several paragraphs of a fairly standard introductory text without due referencing is a less serious case of plagiarism than using a sentence or two this way if they are describing a new, astonishing idea.

Just like the “extent dimension” helps in thinking about plagiarism, so does the “type of content” category. But nor does this category capture what is essential about plagiarism or its normativity. Granted, since new research does bring new results (whether similar to old ones or not), unreferenced reuse of others’ results always involves plagiarism, while reuse of short passages of standardized technical descriptions never does. But it is nevertheless incorrect to claim that you can sort instances on a scale from less serious to more serious depending on type of content. For instance, although in most cases it is worse to plagiarize results than methods descriptions, there are occasions when it is not, namely, when the method is the main contribution of the paper. The seriousness depends on originality rather than on type of content: “Regardless of where the main merits of a paper are located, plagiarism of those parts is more reprehensible than plagiarism of less important parts” (Helgesson and Eriksson 2015, p. 99).

Table 1. Dimensions of plagiarism

Table 1. Dimensions of plagiarism

The type of content matters normatively also in other ways. Plagiarism of data or results may distort meta-analyses by presenting as new that which is not (a negative consequence). Plagiarism of data/results furthermore constitutes fabrication, since previous work of others is presented with the pretense of being new. As noted above, republishing already published results also constitutes redundant publication.

As touched upon when discussing type of content and extent of plagiarism, what to a large extent determines the seriousness of different instances of plagiarism is the originality of that which is plagiarized. Exactly how this originality value is to be specified so far remains unsettled. One way to see it is that the value “stems from the novelty and potential of affecting knowledge development within the specific field” (Helgesson and Eriksson 2015, p. 99). This would suggest that what determines seriousness of plagiarism is not so much the uniqueness as the unique contribution to knowledge development. If so, the ultimate yardstick for seriousness relates to the scientific contribution made by that which is plagiarized. This suggestion would fit with the common intuition that plagiarism of ideas, results, and novel means to reach them is more serious than plagiarism of text.

Regarding attribution, plagiarism is worse if literal reuse is neither cited nor quoted, compared to when it is cited but without quotation. Also using an idea without giving credit to its source is worse than leaving quotation marks out, while citing, when text is literally reused. However, as with the other dimensions, the guiding light for what makes a case of plagiarism more or less serious is the originality value of that which is plagiarized. If the plagiarized idea is of meager value, then cutting and pasting large chunks of text without proper referencing may be worse.

Above we distinguished between what is wrong with plagiarism as such and consequences of plagiarism. The “intentionality dimension” brings in a third normative aspect. It does not concern plagiarism as such, nor does it concern the consequences of plagiarism. Rather it concerns the morality of the agent, the plagiarizer. There is a difference in the blameworthiness of the individual depending on whether or not the plagiarism is intentional. If intentional, then it involves dishonesty by being intentionally misleading, while an ignorant plagiarizer cannot be accused of dishonesty. However, a remaining criticism can be that the person should be aware of proper citation procedures and therefore can be blamed for being ignorant, which in turn may or may not be intentional.

Blameworthiness in relation to plagiarism may depend also on other things, such as seniority and familiarity with the language in which the work is published: the more senior the researcher, the less excusable is ignorance and disregard of proper citation rules; the more proficient in the language of the article or book, the less excusable to take inappropriate shortcuts in writing it.

When it comes to the normativity of plagiarism among students, the following arguments are common: (1) Plagiarizing is bad for those who do it, because it replaces a good learning opportunity, namely, to write the piece of work the proper way. For the sake of quality of education, it is therefore important to stand at bay against plagiarism. (2) Plagiarism is a way of cheating. By not doing the assignment properly, while pretending to do so, plagiarizers act deceitfully toward their teachers and get an undeserved advantage over their peers. The latter since they escape the effort needed to do the assignment correctly – and perhaps in terms of quality, compared to what they would have accomplished without cheating. The act is, thus, unjust and the outcome is unfair. (3) Also in this context, plagiarism involves misplaced attribution of credit.

There might seem to be a drastically different approach to plagiarism in the arts, where a spirit of “no boring rules should restrain the freedom of creative artists” is nurtured. Nevertheless, art and literary works to a considerable extent consist in repetitions and variations of the tradition. Thus, plagiarism along with imitation, parody, ironic retake, and deliberate assemblages is part of the living tradition (Eco 1990). Borrowing from others without explicit reference to the source of inspiration is both common and encouraged. However, it can be questioned whether the differences are that great. While using ideas from others and integrating them into something new of one’s own is cherished, using the ideas of others while passing them off as your own, as in plagiarism of style, is not. It is one thing that artists do not add footnotes with Bibliography : to their paintings, sculptures, or installations, but quite another not to admit the influence of others when asked. While the career of an artist very much depends on the appreciation of his or her art production, getting the appropriate credit for influencing and inspiring others, and thereby for having an impact on the development of one’s craft, matters for the individual’s place in the history of art.

Explaining Plagiarism

Some of the explanations why students and researchers plagiarize are the same as those explaining other kinds of misconduct in education and research:

- Ignorance: some students and researchers are unaware of what is acceptable practice. Sometimes universities are not clear in their communication about what constitutes plagiarism or about their attitude toward it, and teachers do not always feel they have sufficient time to teach and practice appropriate writing and citing manners.

- Indolence: some might regard it pointless to put in the effort when there are easier routes to the same goal.

- Opportunity: modern information technology has made plagiarism more effortless because of the massive changes in access to information over the last few decades. For students willing to take shortcuts, there are websites offering ready-made essays on a vast number of topics. And the opportunities to cut and paste from various sources on the Internet are as good as limitless. For researchers with requisite access, most research journal articles are available in electronic form. Image manipulation is also relatively easy thanks to widely available software.

- Competition: publications are essential in any researcher’s CV, and the pressure to publish, in order to gain positions or external funding, might tempt some to plagiarize. Similarly, some students might think that they increase their chances of getting good grades or finish their assignment on time, by cutting and pasting from other sources rather than by letting the form and content of the text be a result of their own efforts.

- Poor control: to the extent that plagiarism control and control of misconduct generally are limited, it will make that option more tempting.

- Notions of what others do: those who believe that plagiarism is common and expect their peers to plagiarize tend to be more inclined to plagiarize themselves.

Limited proficiency in English is identified by many as an explanatory factor behind plagiarism, especially among those who learn English as a foreign language. Fear of failure and limited experience with essay writing can also pressure students to plagiarize. Studies further indicate that students plagiarize when they lack the time to accomplish a task or when they are uninterested in the topic (Pennycook 1996; Hayes and Introna 2005; Sun 2013).

It has been proposed in a number of studies that cultural differences explain a variation in attitudes toward plagiarism (Hayes and Introna 2005; Helgesson and Eriksson 2015; Pennycook 1996; Stretton et al. 2012). One important factor is the attitude toward and treatment of authorities. For instance, according to Pennycook (1996), using other authors’ words, without rephrasing, is for students in China a way of showing them respect. This cultural practice is deeply rooted. Stretton and colleagues (2012) have argued that cultural differences in familiarity with the notion of individual property may also affect the understanding of plagiarism – unless you have the idea of an individual right to intellectual efforts, rather than simply seeing them as contributions to a common resource, it might be difficult to perceive the normative relevance of plagiarism and therefore the need to distinguish between what others have written and what you have phrased yourself.

Pedagogical differences also contribute to explaining variations in relation to plagiarism. A stress on memorization and recall-type examinations of the studied material, rather than on critical reflection, arguably promotes a writing practice that goes counter to ideas of the need to rephrase. In China, much of the rest of Asia, and Greece, memorization and assumed authority of the authors encountered in the texts are central aspects of the students’ learning experience (Hayes and Introna 2005; Pennycook 1996). However, these cultural and pedagogical differences do not fully explain why explicit quotations are not used.

As noted above, Internet has dramatically increased the ease by which plagiarism can be carried out. Perhaps a cultural change has also taken place in its wake. Studies indicate that a cut-and-paste practice, without providing citations or quotations, has become widely established among high school as well as college students as a way of writing assignments (Sun 2013). It has been suggested that Internet has changed the perception of the writing of others among many people, especially in younger generations, in a direction where it is not considered wrong or cheating to plagiarize, because anything found on the Internet does not belong to anyone, does not need to be accredited, and is free to use (Sun 2013).

As part of the explanation to differences in attitudes toward plagiarism, rather than an explanation of the occurrence thereof, it has been pointed out that text plays a partly different role in different research areas (Helgesson 2014). In areas such as history, philosophy, literary studies, and anthropology, text has a central function as mode of presentation of results, while images, graphs, tables, and mathematical formula take on this role in much of medicine and the natural and engineering sciences. This might partly explain a difference in attitudes toward text plagiarism between research fields. Also, different research traditions may vary in their stress of the relevance of eloquence in writing. Finally, plagiarism seems more common in articles with many authors compared to those with fewer, arguably because multiauthorship brings with it a dilution of responsibility (Sun 2013). But it could also be the case that multi-authorship occurs mainly in fields where text plays a less significant role.

Detecting Plagiarism

The traditional approach to detecting plagiarism is that readers who find images or phrases in an article or book that they think they recognize from someplace else try to recall the original source and undertake further investigations. While modern information technology has made plagiarism more effortless, the technology development has also made it easier to detect plagiarism. There is a variety of plagiarism detection software, drawing on large databases, identifying text segments that are matching previously existing text. Such software is used to control student essays, thesis summaries, and academic articles. There is some evidence that the implementation of such software reduces the number of instances of plagiarism. The software has also shown to be useful as a formative learning tool, since it gives students feedback on the grade of independence of their writing (Sun 2013). Thus, it can be used for constructive purposes relating to awareness of plagiarism as a problem and the need for proper paraphrasing and referencing when using sources from the Internet.

However, plagiarism detection tools have some important limitations (Helgesson and Eriksson 2015; Sun 2013). Firstly, what they do, strictly speaking, is not to detect plagiarism, but to detect text overlapping. To judge whether a certain amount or proportion of text overlapping constitutes plagiarism requires evaluation. As pointed out above, using preset lengths of word strings or percentage levels cannot handle evaluation in a normatively satisfying way. Secondly, the software does not distinguish between different kinds of overlapping text, for instance, whether it is general knowledge, descriptions of standard procedures, or something novel or personally phrased. Also this needs to be evaluated by someone using the software as a detection tool. Thirdly, not all sources are included in the software’s databases. Fourthly, the software is presently unable to detect plagiarism across languages. Fifthly, plagiarism detection software cannot detect plagiarism of ideas, for instance, when the original occurrence is not documented (as when researchers share their ideas over a cup of coffee) or when the idea is used by the plagiarizer rather than stated. Finally, plagiarism detection tools do not detect plagiarism of images or tables.

Counteracting Plagiarism

Two major alternatives have been discussed when it comes to counteracting plagiarism: (1) exposure and punishment or (2) education and cultivation of a non-plagiarizing culture. In order to expose more than a random selection of cases, there needs to be some kind of systematic detection of plagiarism, such as the consistent use of detection software. And for detection to be meaningful beyond providing statistics, some measures need to be taken whenever plagiarism is exposed. Removal of any advantage gained by plagiarizing is one potential step, such as retracting published articles or failing plagiarizing student reports. Other disciplinary measures are salary deductions, ban from doing research, or temporary suspension from education, from being eligible to apply for research funds, or from being allowed to publish in the offended journal.

Education about plagiarism, proper referencing, and paraphrasing is a proactive approach to counteracting plagiarism. In discussions on plagiarism among students with English as a foreign language, the thrust has been on helping students develop the required language skills, so that they no longer feel the need to take shortcuts in order to manage their assignments. It has further been suggested that courses on research ethics for doctoral students and other researchers should lead up to an ethics training certificate compulsory for anyone doing research requiring ethical approval (Kombe et al. 2014).

As has been noted in relation to education about scientific misconduct generally, there is a risk that research ethics courses have an effect opposite to the one intended; thus, courses covering plagiarism avoidance may in fact remind students about the plagiarism option and clearly hint that they would not be alone if they went along, while indicating what precautions might be needed to avoid being caught.

Cultivating a good study or research environment takes time and is particularly difficult if important incentives are pulling in the opposite direction. Environments where plagiarism will be a less likely choice are characterized by openness as to what the individuals are up to, social control, clear rules, good learning support, and role models focusing on the substance (content) of the activities, rather than on their measurements and outer rewards. The use of mentors might be one way to facilitate cultivation of proper attitudes and the promotion of research integrity (Kombe et al. 2014).

Changing Standards Regarding Text Plagiarism

Plagiarism detection in the academic world, exposing instances of scientific misconduct involving fabrication, redundant publication, and undue acquisition of scientific credit, is relevant to all research areas. But it has been suggested that detection of overlapping text as such is of varying interest, depending partly on the research field, partly on the functions of different sections of a research article. Firstly, in most research articles, some parts cover standard material, such as a presentation of the relevant background or a description of applied methods. Here the point is to present the familiar in an easily recognizable way, in order to then be able to move onto the original contribution of the paper. One could, thus, argue that while originality when it comes to ideas and ways to explore them is highly esteemed, originality in the description of shared knowledge and starting points is at best odd, at worst confusing and misleading. Secondly, as noted above, text plays a partly different role in different research areas. This might justify a differentiation in approaches to text plagiarism, with the underlying idea that the practice best suited to the promotion of knowledge development should be opted for in each research field.

In several research fields, there is already a consensus that Bibliography : are not required for descriptions of what is taken to be well-established knowledge within the field (Anderson and Steneck 2011). For instance, moral philosophers trained in the analytical tradition are considered free to analyze an idea or policy suggestion from a utilitarian perspective without citing any literature on utilitarianism, unless the suggested interpretations are unusual or contested and therefore in need of support.

A way to take this a step further would be to allow literal reuse of text containing descriptions of established background perspectives, methods, specifications of the study’s limitations, etc. without showing that it is a quotation and, if very general, without referencing (Bouville 2008; Helgesson 2014). However, this proposal might seem to present as new something that is already familiar in areas like medicine and much of the natural sciences. Newcomers in these fields are often encouraged by their peers to reuse their previous methods descriptions or cut and paste from colleagues, without using quotation marks. But the literature shows that there is no unison in practice and a potential for double standards, where research peers may say one thing and journal editors another (Wager 2014). For instance, in a study of the message in journal editorials regarding plagiarism and self-plagiarism, Roig found a great variety in attitudes: while some editors expressed not having any problems with authors reusing, for instance, large portions of methods sections or even entire methods sections, other editors discouraged all such practices (Roig 2014). For a successful change to take place, there has to be a broad and open agreement among journals and research organizations concerned on what is permitted.

There are a number of advantages with treating some types of word strings, phrases, and paragraphs as a general resource free to use literally or free to use if a reference is given (without explicitly quoting), particularly if such a change is supported and facilitated by reporting guidelines (Helgesson 2014):

- It would avoid the burden of rephrasing for the sake of rephrasing.

- The potential problem of procedure drift would also be avoided, i.e., the risk that a continuous change in description of research methods will slowly, and unintendedly, alter these methods.

- It would support researchers with insufficient language skills to find appropriate ways to present their research.

- It would probably reduce required writing time also for many others, which could be reallocated to reflections on the content of the paper.

- If this change were supported by reporting guidelines, then it could not only provide preferred ways to describe procedures but also make papers more comprehensive by improving structure and providing checklists for required content.

- Increased similarity of papers, both in terms of structure and in terms of terminology, would enhance machine readability, a potential advantage in times of big data.

A potential criticism of the suggested practice is that trust in the authors would be threatened. There might also be a risk for a slippery slope regarding what kinds of copying are accepted (Bruton 2014). Against this can be argued that if a sharp line is drawn between what is permissible and not, e.g., copying background material and copying results, then there is no reason to believe that the division could not be maintained (Bouville 2008).

Conclusion

While plagiarism is treated as a paradigmatic example of scientific misconduct in research ethical guidelines, both the concept “plagiarism” and the normative implications of plagiarism have been given fairly limited attention in the bioethics literature. However, it is an issue of considerable practical import for educational systems and for research. While continuous work to inform, influence attitudes, and detect plagiarism is needed, it may also be relevant to reconsider our overall attitudes toward plagiarism in relation to text. Perhaps it would be more conducive to progress in many areas of research if focus shifted from detection of text overlapping to best practices for reporting research results, in order to facilitate comprehension and comparison. To this end, it might be preferable to abandon the idea of a right to acknowledgment for the creation of text.

Bibliography :

- Anderson, M. S., & Steneck, N. H. (2011). The problem of plagiarism. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations, 29, 90–94.

- Bouville, M. (2008). Plagiarism: Words and ideas. Science and Engineering Ethics, 14, 311–322.

- Bruton, S. V. (2014). Self-plagiarism and textual recycling: Legitimate forms of research misconduct. Accountability in Research: Policies and Quality Assurance, 21(3), 176–197.

- Eco, U. (1990). The limits of interpretation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Hayes, N., & Introna, L. D. (2005). Cultural values, plagiarism, and fairness: When plagiarism gets in the way of learning. Ethics & Behavior, 15(3), 213–231.

- Helgesson, G. (2014). Time for a change in the understanding of what constitutes text plagiarism? Research Ethics, 10(4), 187–195.

- Helgesson, G., & Eriksson, S. (2015). Plagiarism in research. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 18(1), 91–101.

- Kombe, F., Anunobi, E. N., Tshifugula, N. P., Wassenaar, D., Njadingwe, D., Mwalukore, S., Chinyama, J., Randrianasolo, B., Akindeh, P., Dlamini, P. S., Ramiandrisoa, F. N., & Ranaivo, N. (2014). Promoting research integrity in Africa: An African voice of concern on research misconduct and the way forward. Developing World Bioethics, 14(3), 158–166.

- Moffat, B., & Elliot, C. (2007). Ghost marketing: Pharmaceutical companies and ghostwritten journal articles. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 50, 18–31.

- National Science Foundation. (2012). Research misconduct. 45-CFR-689.

- Okonta, P., & Rossouw, T. (2013). Prevalence of scientific misconduct among a group of researchers in Nigeria. Developing World Bioethics, 13(3), 149–157.

- Pennycook, A. (1996). Borrowing others’ words: Text, ownership, memory and plagiarism. TESOL Quarterly, 30, 210–230.

- Roig, M. (2014). Journal editorials on plagiarism: What is the message? European Science Editing, 40, 58–59. Stretton, S., Bramich, N. J., Keys, J. R., Monk, J. A., Ely,

- A., Haley, C., & Wolley, M. J. (2012). Publication misconduct and plagiarism retractions: A systematic, retrospective study. Current Medical Research & Opinion, 28, 1575–1583.

- Sun, Y. (2013). Do journal authors plagiarize? Using plagiarism detection software to uncover matching text across disciplines. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 12, 264–272.

- Wager, E. (2014). Defining and responding to plagiarism. Learned Publishing, 27, 33–42.

- Carroll, J. (2007). A handbook for deterring plagiarism in higher education (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development.

- CODEX – rules & guidelines for research. Website at codex.vr.se

- Retraction Watch. Tracking retractions as a window into the scientific process. Website at http://retractionwatch. com

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.