This sample Resuscitation Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

This entry underlines the enormous importance of ethical decision making in order to draw attention to the need to establish an appropriate balance between autonomy and self/other-oriented responsibilities in the cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) context.

Introduction

For health care professionals, whether doctor or nurse (and regardless of specialty), there are few things harder than not intervening when a patient suffers a cardiac arrest (Ewanchuk and Brindley 2006). The huge technical potential of intensive medicine and its associated duties have created the need for an enhanced sense of responsibility and the development of new branches of medical reflection and education: more precisely the sustainable management of resources and the ethical, social, and scientific considerations concerning the limits for the cardiopulmonary resuscitation (hereafter only CPR) intervention.

From the end of the twentieth century, the physician’s capacity to intervene, using very innovative and sophisticated techniques, has increased enormously, without adequate consideration regarding the impact of these interventions on the quality of life of those critically ill. Critical care is an integral part of hospital care. In intensive care death and dying situations, previously private, traditionally spiritual or religious events involving family and friends, are in today’s world often public and technological, therefore, few areas of medical ethics raise such strong and diverse views on the issues regarding the end of life. Sophisticated technological support has allowed very critical ill patients to survive longer; however, it is becoming increasingly accepted that continued aggressive care may not always be beneficial.

The current technique of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), applying expired air ventilation and closed chest cardiac massage, was developed at the beginning of the 1960s by Kouwenhoven. It was an easy-to-learn method, which was soon disseminated: “Anyone, anywhere, can now initiate cardiac resuscitative procedures; all that is needed are two hands” (Kouwenhoven et al. 1960). Originally developed for the treatment of sudden and unexpected cardiac arrest in supposedly healthy persons, after the first successes this treatment was extended to cardiopulmonary arrest of any origin. CPR is now considered a routine emergency treatment, but the reflex-like initiation of CPR has also entailed criticism (Mohr and Kettler 1997). In 1985 an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association stated: “In some way we have wandered from treating sudden unexpected death to practising universal resuscitation” (Hayes 2013).

Do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders have been in use in hospitals worldwide for almost 50 years. In many cases, the use of DNR is appropriate and has a reasonable likelihood of improving outcome.

Nonetheless, as currently implemented: (1) discussions do not occur frequently enough and occur too late in the course of patients’ illnesses to allow their participation, (2) many physicians fail to provide adequate information to allow patients or surrogates to make informed decisions and (3) inappropriately extrapolate DNR orders to limit other treatments (Yuen et al. 2011), DNR orders sometimes fail to adequately fulfill their two intended purposes – to support patient autonomy and to prevent nonbeneficial interventions. These failures lead to serious consequences. Patients are deprived of the opportunity to make informed decisions regarding resuscitation, and resuscitation attempts are unlikely to benefit the patient, and may not be in accordance with the values and treatment goals of the patient and family (Marco 2005).

Understanding the literature regarding resuscitation, outcomes, factors relating to outcomes, and alternatives, are essential to medical decision-making regarding resuscitation. The process of deliberation, decision, and the assumption of responsibility in relationship to one’s behavior is a function of the totality of the [individual’s] being (McMillan 1995). It may be argued that the nature of a resuscitation attempt, demanding immediate and often irreversible interventions, makes ethical deliberation impossible. Even though CPR is an emergency measure, its practice, just as that of any other medical procedure must be framed in a previous ethical reflection in order to allow for an ethical decision making (Mohr and Kettler 1997). The goal of cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making is to meet patients’ wishes and needs by choosing an appropriate treatment; therefore, these choices must occur within an ethical framework dominated by two key precepts: respect for patient autonomy, and physician responsibility framed by the physician’s duty to respect beneficence and nonmaleficence and the obligation to ensure just distribution of resources and by patient dignity, integrity, and vulnerability. Thereby, this entry questions the appropriate balance between autonomy and self/other-oriented responsibilities in resuscitation procedures.

Ethical Deliberation And Decision In Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

Ethical deliberation and ethical decision making must ensure participation and the right to disagree; therefore, it should reinforce that, in the author’s opinion, the use of the term “order” is not appropriate for use in such complex and difficult ethical decisions. For this reason the accuracy of the terms is essential in defining the terms suitable for a conceptual approach.

While the concept may be understood in the clinical context, the term “order” condenses an ethical difficulty that is crucial to clarify: the concept of “order” could be understood as implying a relationship of conflict or of authority, inconsistent with the complex structure that represents the therapeutic relationship and an ethical decision, not only between health professionals, but also with the very sick and their relatives. Therefore the term “order” both in DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) and DNACPR (Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) may be replaced by “decision.”

Cardiac arrest (CA) is a major health problem and survival from cardiac arrest depends largely on prompt initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cardiac arrest occurring in the intensive care unit (ICU) represents a specific sub-group, which differs in several ways from cardiac arrests occurring outside the hospital or in other areas of the hospital. Data on out-of-hospital (OHCA) and in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) are accumulating but data on incidence and outcome of intensive care unit cardiac arrest (ICUCA) are scarce, and appear to be of a highly variable quality (Efendijev et al. 2014).

A review of in-hospital cardiac arrest studies document incidences in the range of 1–5 per 1,000 hospital admissions but with widely variable survival rates (0–42 %). The overall incidence of adult in-hospital cardiac arrest was 1.6 per 1,000 hospital admissions with a median across hospitals of 1.5. Overall unadjusted survival to hospital discharge was 18.4 % (Nolan 2014).

Due to the medical and ethical complexity of the decision, the clinical judgment requires the integration of medical scientific concepts into observation and perception; being responsive to evaluate complex situations requires being sensitive to the demands of evaluative reasons. Three steps have been identified in CPR decision making (Hayes 2013) which could be representative of the aforementioned demands: (i) technical analysis and judgment about the patient’s illness, disease trajectory, and expected response to CPR; (ii) ethical analysis about the application of that technical judgment, and (iii) a discussion with the patient and/or family that seeks to understand the patient, their values, and the moral implications of providing or withholding CPR.

These steps include, at least partially, working out the combined effect of different factors that are in play at the same time. Therefore, ethical reflection on principles and good value judgment should be of utmost importance.

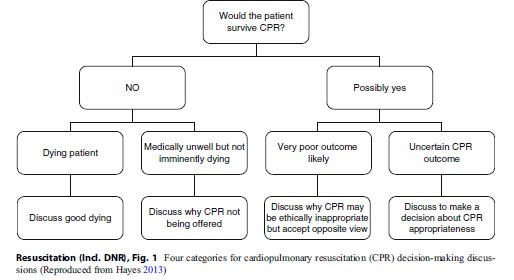

The categories for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) decision-making discussions proposed by Hayes (2013) could offer a possible strategy to enable a better deliberation and consequent decision on this issue. Four patient categories have been identified by the author: two categories of patients not expected to survive a CPR attempt and two categories who may survive. The significance of these categories is that for each, there is a different aim and a different ethical deliberation/ decision. It is not always possible to predict outcomes with absolute certainty, but any uncertainties can be addressed within the discussion. Also, a decision about CPR can only be understood within the context of the patient’s overall medical condition and management.

Figure 1 Four categories for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) decision-making discussions (Reproduced from Hayes 2013)

Figure 1 Four categories for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) decision-making discussions (Reproduced from Hayes 2013)

Patients that could be included in categories 1 and 2 are patients where a technical medical judgment has been made that CPR could not reverse cardiac arrest. For these patients, CPR can neither prolong life nor provide greater comfort in dying and would not be of benefit and may do harm by increasing pain and suffering being these patients stripped of their dignity. Offering a nonbeneficial treatment is not respectful of patient dignity, autonomy and is irresponsible. However, given the likelihood that CPR might be expected, it will be important to have a CPR-related discussion so there is no harmful misunderstanding. The patient’s and family’s autonomy, in a shared decision making model that will be explained latter, is respected by explaining why CPR would not be appropriate. These discussions should be deliberative and participative, conveying an understanding that CPR should not be provided because there would be neither technical nor ethical reasons to do so (Fig. 1).

Categories 3 and 4 are patients for whom CPR is judged to have some potential to reverse cardiac arrest. There will be ethical implications for both providing and withholding CPR. Whether or not CPR will be beneficial or harmful will depend on the patient decision and moral values, and hence, a decision-making discussion will be required. When the patient has capacity to participate in the decision, respect for autonomy would mean the patient is permitted to determine whether or not CPR would be in his best interests. When the patient lacks capacity to make an autonomous decision or an advanced directive is not in place, then the family and clinician will need to make a decision that is in the patient’s best interests. If a patient lacks decision-making competence, physicians in collaboration with other clinicians (including nurses) should have the final decision-making authority. However, in order to determine patients’ wishes, information shall be obtained from the closest relatives about the patient’s presumed consent.

Autonomy In The Resuscitation Context

Until at least the middle of the twentieth century patients relied on physicians to tell them what to do when faced with a medical decision, and for the most part, the latter gladly accepted this responsibility. Eventually (however), patients and doctors came to realize that this paternalistic approach to medical decision-making placed far too much power in the hands of physicians, however beneficent their intent. Therefore, the patient-physician relationship is a persistent issue in medical ethics reflection.

There is a growing recognition and acceptance of the need to embrace patient-centered care (PCC) approaches in the delivery of health care. PCC is a standard of practice that demonstrates a respect for the patient, as a person and the doctorpatient relationship as an encounter characterized by responsiveness to patient needs and preferences , using the patient’s informed wishes to guide activity, interaction and information giving, and shared decision-making (Pelzang 2010). Governments across the world as well as international organizations, patient and health policy organizations, and lobbying groups are all emphasizing the need for health care to be more explicitly centered on the needs of the individual patient. There is a quite high level of consensus emerging from literature: there is acknowledgement of the centrality of the patient experience; the need for respect and the expressions of values and beliefs; the need to take an integrated approach to care; to communicate effectively; and to share in decision-making processes (Kitson et al. 2013). What does not emerge in the medical texts is the way the different PCC dimensions should interact with each other in order to guarantee the best interest of the patient, the best interest of the physician, and the best interest of society.

Therefore, the ethical virtues of trustworthiness and respect must be integrated with other ethical principles commonly observed in health care (dignity, autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence responsibility, integrity, vulnerability, and justice). These normative ethical principles used in medical decision-making together with the dimension of PCC can be applied to the CPR decision, in order to describe a way for thinking ethically about it (Hayes 2013).

The promise of increased choice is now one of the key influences on new medical technologies. Despite the high regard for the principles of patient autonomy in most North American and some European countries, in reality most patients are too ill or too sedated to participate meaningfully in decision-making in the end of life. In fact, the main problem about DNR orders lies in the fact that physicians can only know patient preferences if there is true patient-physicians relationship. In the case of CPR this entails that discussion about resuscitation has occurred. This discussion must ensure proper understanding of what it would mean to choose the DNR option and must involve an ethical and compassionate exploration of end-of-life wishes.

Although physicians are often involved with how their critically ill patients die, it is unclear where and when patients would like DNR conversations to take place or with whom. Improved knowledge about patient preferences will assist caregivers in facilitating these life-and-death discussions, while respecting patient autonomy and decreasing the number of unwanted and unnecessary interventions. For that reason, Cherniack (2002) stated that the most appropriate time for the first discussion of DNR “orders” is when a person is healthy. However, clinical experience and past literature indicate that many DNR discussions occur late in a patient’s course of illness, often in a crisis setting or when the patient is no longer competent (Eliott and Oliver 2007).

Heyland et al. (2003) stresses that most substitute decision-makers for end of life patients wanted to share decision-making responsibility with physicians and that overall they were satisfied with their decision-making experience. As Gracia (2003) stresses, greater autonomy also involves greater responsibility concerning the options taken by the patient or the health professional. However, the relationship between the two principles is much more profound and complex. On this point, it could be prudent to replace the concept of autonomy with the concept of responsible autonomy. Relational accounts encourage clinicians to consider patients’ autonomy in decision-making situations.

Responsibility In The Resuscitation Context

The idea of responsibility has a long history, notwithstanding being a relatively recent concept with a specifically moral dimension being only attained in the twentieth century. The notion of responsibility was made explicit and generally accepted during the Middle Ages and was used mostly as an adjective (“responsible” for an act or omission), not as an effective reality, in other words, morphologically like a noun (“responsibility”).

In etymological terms, the verb “to respond” is polysemic: resspondere, to engage oneself (spondere) before somebody; to value (ponderare) the things (res). From the philosophical point of view, the intention is not to make moral judgments but to understand and clarify the meaning of “responsibility” in order to emphasize its importance in the context of CPR. It should be underlined that the decision for CPR where acutely ill patients (medical vulnerability), most of them not able to make an autonomous decision (cognitive and juridical vulnerability), are given the most technologically and expensive advanced life sustaining treatments (allocation vulnerability) in a very stressful environment (infrastructural vulnerability), must be framed on the principle of responsibility (Kipnis 2001).

Therefore, bearing in mind that the principle of responsibility must be at the core of medical practice, this part of the entry will analyze the contributions of some thinkers who have placed special emphasis on the theme of “moral responsibility,” and thus attempt to shed some light on this principle within the specific context of CPR.

In the event of circulatory arrest, the patient is in danger of dying within minutes. Any resuscitation attempt aims at averting death (maleficence) and saving life (beneficence). However, due to the potential poor outcomes, that have been previous described, of this procedure it must be asked if further damage could be inflicted by a resuscitation attempt. For some patients, resuscitation means an extension of the process of dying by hours or days, often without regaining consciousness and accompanied by the concomitants of intensive care treatment, such as tracheal intubation and artificial respiration (Mohr and Kettler 1997). Therefore, according to Ricoeur, it is the extent to which I act towards the other in a responsible manner which validates my ethical behavior (Ricoeur 1995). I have the normative “responsibility to protect” but, more than that, I have a moral “responsibility to protect.”

For Levinas, ethics is happens – or not – when the self-certain ego becomes disturbed (shaken, questioned) by the proximity, before me, of the absolute Other, the absolute singular (the Infinite). Therefore, the physician being confronted by the face of a critical care “other,” his or her first ethical task is to accept the extraordinary “otherness” of the patient, expressed by that patient’s visible vulnerability, which constitutes an ethical cry for help and care, and to fully assume responsibility.

Health professionals shaken by a sudden cardiac arrest, have the potential to reverse premature death by CPR. Sadly, they also have the potential to prolong inevitable death, to cause discomfort, to increase emotional distress, and to consume enormous resources. In some instances, to save the patient’s life might not be the final goal. Ethical decision-making must take into account the potential futility of treatment and must consider the patient’s autonomy by respecting his individual hierarchy of values (Mohr and Kettler 1997). However, as previous mentioned, when CPR may do harm by increasing pain and suffering, offering a nonbeneficial treatment is not respectful of patient dignity, autonomy, and is irresponsible. Rather than perceiving that physicians are doing nothing, something has indeed been done; the integrity of the patient has been preserved and respected and they have been allowed to die with dignity. Complying with these wishes represents one of the greatest challenges that physicians must face and is the core of medical responsibility (Ewanchuk and Brindley 2006).

Hans Jonas, by declaring responsibility as a principle, constitutes another landmark in the reflection on its moral dimension and in its importance for the ethics in life sciences (Jonas 1995). Jonas’s responsibility could be identified in the context of resuscitation attempts as deriving from two different roots: the responsibility to the future generations (of all future patients and sustainability of the health care system) and the responsibility to the future (of my patient).

The appropriate allocation and stewardship of resources is an important consideration when making decisions regarding invasive, costly, or lengthy procedures. Typically, a single attempted CPR in the emergency department costs thousands of euros and monopolizes the time and efforts of several health care professionals (Marco 2005). Also, performing CPR which is inappropriate or futile may delay or prevent emergency treatment of other patients with a better chance of survival (Mohr and Kettler 1997).

It has become evident that understanding long-term survival, morbidity, and quality of life (QOL) after resuscitation is as important as dealing with short-term survival (Williams and Leslie 2008).

Understanding the consequences of resuscitation informs preventive measures that can be integrated into patient management and enable improvements in the quality of end of life care; whatever model is chosen, appropriate follow-up for survivors of CPR and their families is worth pursuing. So, in this context responsibility is a social relationship of equal and reciprocal recognition of rights, which in order to operate requires articulation and deliberation with other ethical principles. It implies both reciprocity and accountability (Groves 2006). A new concept of accountability is also required, one that is rooted in a shared concept of truth that sets out how agents must take responsibility for the long-term effects of their current activities.

Regarding the principle of responsibility framed by the physician’s duty to respect beneficence and nonmaleficence and the obligation to ensure just distribution of resources and by patient dignity, integrity, and vulnerability in the resuscitation context, three distinct categories may be considered: current, future, and retrospective responsibility. Current responsibility involves the doctor’s duty to act in a responsible manner in the immediate situation. Future responsibility involves evaluating the post-CPR patient situation, resulting from the interventions of health professionals. Retrospective responsibility involves postevaluation of the CPR actions previously undertaken together with team reflections concerning the decision. All these forms of responsibility are interconnected. The question here is how far a physician is responsible not only for the current effects of his/her action, but also for the possible future effects, as well as for the prevention and the avoidance of possible future occurrences (McMillan 1995; Gracia 2003).

Jonas affirms responsibility towards the future and Levinas’ explains ethics as responsibility. Therefore, Levinas and Jonas are two highly significant landmarks for the reflection regarding the moral dimension of responsibility in resuscitation context and its importance for ethics. However, there is an insurmountable distance between the self and the Other and the present and the future; there is a need to resort to the concept of Aristotelic Phronesis (van Niekerk and Nortje 2013) and of Ricouerian prudence. Without them, Jonas and Levinas’s approach to responsibility proves quite risky if applied to the practical context: this distance between the self and the Other and between the present and the future could, if not framed within prudence, represent the denial of responsibility (Tatranský 2008).

Conclusion

In CPR decisions, the moral responsibility of the health professional must find common ground or even a common ethical platform, in order to build a consensual policy for people with different values and principles. In consequence, the most balanced formulation for a model for ethical CPR decision-making that assures a correct understanding of patient autonomy and the right articulation with the other principles could be synthesized by Pellegrino and Thomasma’s (1993) citation: “attempt[ing] to place the medically good within the larger context of the patient’s total good.”

Paul Ricoeur perspective includes both Levinas and Hans Jonas theories; following the reasoning of the aforementioned authors, it might suggest that this idea of responsibility in the CPR context could be applied: (1) to the object of responsibility, “the other” (similar to the Levinasian formulation) who is in a situation of vulnerability, fragility, in a critical circumstance, often unable to communicate either by the effect of his own illness or of the effects of necessary medication or treatments; (2) to the responsibility in the future (similar to the Jonassian designation) either concerning this patient follow-up or of the others who may come to need an health intervention; and (3) to prudence that must be exercised in decisions through recourse to DNR “decision” guidelines (Groves 2006) and accountable measures of the outcomes.

Bibliography :

- Cherniack, E. P. (2002). Increasing use of DNR orders in the elderly worldwide: Whose choice is it? Journal of Medical Ethics, 28(5), 303–307.

- Efendijev, I., Nurmi, J., Castrén, M., & Skrifvars, M. B. (2014). Incidence and outcome from adult cardiac arrest occurring in the intensive care unit: A systematic review of the literature. Resuscitation, 85(4), 472–479.

- Eliott, J. A., & Oliver, I. N. (2007). The implications of dying cancer patients’ talk on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and do-not-resuscitate orders. Qualitative Health Research, 17(4), 442–455.

- Ewanchuk, M., & Brindley, P. G. (2006). Ethics review: Perioperative do-not-resuscitate orders – Doing “nothing” when “something” can be done. Critical Care, 10(4), 219–222.

- Gracia, D. (2003). Ethical case deliberation and decision making. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 6(3), 227–233.

- Groves, C. (2006). Technological futures and non-reciprocal responsibility. International Journal of the Humanities, 4(2), 57–62.

- Hayes, B. (2013). Clinical model for ethical cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision-making. Internal Medicine Journal, 43(1), 77–83.

- Heyland, D. K., Cook, D. J., Rocker, G. M., Dodek, P. M., Kutsogiannis, D. J., Peters, S., Tranmer, J. E., & O’Callaghan, C. J. (2003). Decision-making in the ICU: Perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Medicine, 29, 75–82.

- Jonas H. (1995). The Imperative of Responsibility. In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Kipnis, K. (2001). Vulnerability in research subjects: A bioethical taxonomy. In: Ethical and policy issues in research involving human participants. Prepared for the National Bioethics Advisory Council of USA. Retrieved from: https://repository.library.georgetown. edu/bitstream/handle/10822/559361/nbac_human_part_vol2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#page=209

- Kitson, A., Marshall, A., Bassett, K., & Zeitz, K. J. (2013). What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(1), 4–15.

- Kouwenhoven, W., Jude, J., & Knickerbocker, G. (1960). Closed-chest cardiac massage. JAMA, 173, 1064–1067.

- Marco, C. A. (2005). Ethical issues of resuscitation: An American perspective. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 81, 608–612.

- McMillan, R. C. (1995). Responsibility to or for in the physician-patient relationship? Journal of Medical Ethics, 21, 112–115.

- Mohr, M., & Kettler, D. (1997). Ethical aspects of resuscitation. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 79, 253–259. Nolan, J. P., Soar, J., Smith, G. B., Gwinnuttd, C., Parrott,

- , Power, S., Harrisone, D. A., Nixone, E., Rowan, K. (2014). Incidence and outcome of in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United Kingdom National Cardiac Arrest Audit. Resuscitation. 85:987–992.

- Pelzang, R. (2010). Time to learn: Understanding patientcentred care. British Journal of Nursing, 19(14), 912–917.

- Pellegrino, E. D., & Thomasma, D. C. (1993). The virtues in medical practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ricoeur, P. (1995). O Justo ou a essência da Justiça. Lisboa, Portugal: Instituto Piaget.

- Tatranský, T. (2008). A reciprocal asymmetry? Levinas’s ethics reconsidered. Ethical Perspectives, 15(3), 293–307.

- Van Niekerk, A. A., & Nortje, N. (2013). Phronesis and an ethics of responsibility. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, 6(1), 28–31.

- Williams, T. A., & Leslie, G. D. (2008). Beyond the walls: A review of ICU clinics and their impact on patient outcomes after leaving hospital. Australian Critical Care, 21(1), 6–17.

- Yuen, J. K., Reid, M. C., & Fetters, M. D. (2011). Hospital do-not-resuscitate orders: Why they have failed and how to fix them. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(7), 791–797.

- Henriot, J. (1990). Responsabilité. In S. Avroux, A. Jacob, & J. F. Mattei (Eds.), Encyclopédie Philosophique Universelle. Les Notions Philosophiques (p. 2250). Paris: PUF.

- Robinson, C., Kolesar, S., Boyko, M., Berkowitz, J., Calam, B., & Collins, M. (2012). Awareness of do-not-resuscitate orders. What do patients know and want? Canadian Family Physician Médecin De Famille Canadien, 58, 229–233.

- Rocha, A. C. (2011). Principio de responsabilidad. In C. Romeo Casabona (Ed.), Enciclopedia de bioderecho e bioética (pp. 1471–1472). Cátedra Interuniversitaria Fundación BBVA, Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao, Spain: Bilbao.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.