This sample Standards Of Care Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. Free research papers are not written by our writers, they are contributed by users, so we are not responsible for the content of this free sample paper. If you want to buy a high quality paper on argumentative research paper topics at affordable price please use custom research paper writing services.

Abstract

Established treatment and/or prevention interventions exist for most medical disorders. These may be single interventions or they may comprise a constellation of health interventions and are widely regarded as “standards of care.” These standards range from no treatment (especially in resource-poor settings) to a gold standard that is international, expensive, and complex. In the context of international multisite research conducted by resource-rich countries in resource-poor countries, standards of care used in the control arm of the study are often controversial especially when placebo is used in this group of participants. Such controversy resulted in global debate in the 1990s when antiretroviral treatment for pregnant women was tested against placebo in several resource poor countries despite the establishment of a gold standard of care in resource-rich countries. Charges of ethical imperialism, ethical relativity, and exploitation of vulnerable populations were expressed in global debates.

Similar arguments emerged in the context of surfactant trials in premature infants in Bolivia. Guidance regarding standards of care in control groups enshrined in the Declaration of Helsinki became extremely controversial in the context of these global debates and increased the sensitivity of research ethics committees to the standard of care being used in clinical trials generally.

This chapter discusses the evolution of the debate on standards of care in clinical trials and adds to the controversy that abounds in research ethics.

Introduction

There are established treatment and prevention strategies in clinical health care for most medical disorders that are regarded as “standards of care.” These standards range from no treatment (especially in resource-poor settings) to a gold standard that is usually international, expensive, and complex. Such standards differ from country to country. They also vary within countries from private to public health systems. As new scientific evidence emerges from medical research, such standards of care may change. The ethical debate around standards of care in research was advanced in the context of placebo-controlled randomized controlled clinical trials conducted in developing countries to prevent HIV transmission from pregnant women to their babies and in the context of surfactant trials in premature infants in Bolivia (Lindsey et al. 2013).

History And Development

In 1994, the results of the first randomized placebo-controlled study on pregnant women infected with HIV were published. It was established that intensive treatment of these women with the antiretroviral drug zidovudine during pregnancy and delivery reduced the transmission of the virus from mother to child by 67 %. From this point onward, zidovudine became the best proved standard of treatment for all HIV-infected pregnant women in the United States (Connor et al. 1994).

The drug regimen used in this landmark study was, however, very expensive and unaffordable to Third World countries. The next logical step was therefore to investigate the possibility of shorter and hence cheaper courses of treatment. The World Health Organization (WHO) urgently called for research in developing countries to explore simpler and less expensive drug regimens. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and other organizations collaborated to set up 16 clinical trials in 12 developing countries around the world. Nine of these studies were conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). One of these trials (conducted in Thailand) was designed as an equivalence study – three short-course regimens were compared and the control group was given the ACTG 076 regimen. However, 15 of these 16 trials were randomized and placebo controlled. HIV-infected pregnant women in the study group were given a short course of zidovudine, and the incidence of transmission of the virus to their babies was established. However, the HIV-infected pregnant women in the control group were given a placebo, which was where the controversy began (Lurie and Wolfe 1997).

The Placebo Debate

In April 1997, Dr. Peter Lurie and Dr. Sidney Wolfe of the Health Research Group (an arm of the watchdog organization, Public Citizen) sent a letter to the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, Donna Shalala, which stated the following:

Unless you act now, as many as 1002 newborn infants in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean will die from unnecessary HIV infections they will contract from their HIV-infected mothers in nine unethical research experiments funded by your department through either [NIH or CDC].

In September 1997, Lurie and Wolfe repeated their charges in the New England Journal of Medicine. They drew attention to the two studies being conducted in the United States where patients in all study groups had unrestricted access to antiretroviral drugs unlike the 15 short-course trials in developing countries where women in the control group were given a placebo (Lurie and Wolfe 1997). The editorial in the same issue of the journal written by the executive editor, Dr. Marcia Angell, supported the views of Lurie and Wolfe. In addition, she drew a parallel between withholding treatment in the placebo group and withholding treatment for syphilis in the infamous Tuskegee study. This set in motion an unprecedented debate on the vertical transmission trials and the ethics of collaborative multinational research (Angell 1997).

The Scientific Debate

The Research Question And Clinical Equipoise

Lurie and Wolfe argued that by conducting a placebo-controlled trial, the researchers were, by implication, asking the wrong question:

Is the shorter regimen better than nothing?

The presumed answer to this question was that anything would be better than nothing. It is an essential prerequisite that when a randomized clinical trial compares two different treatments for a disease, there should be no good reason for thinking that one is better than the other. Hence, investigators need to be in this state of clinical “equipoise” when embarking on a randomized clinical trial. If there is any evidence that one option might be better than the other, then:

not only would the trial be scientifically redundant, but the investigators would be guilty of knowingly giving inferior treatment to some participants in the trial. (Angell 1997)

Hence, randomized clinical trials create the potential for conflict between the investigator’s role as doctor and research scientist. During recruitment, a doctor must ask a patient to submit himself or herself to random assignment to one of two different treatments, one of which may be a placebo. This request can only be ethically justified if the researcher is in a state of genuine uncertainty regarding which treatment is better. This is so because randomization is inconsistent with doing one’s best for the patient as a doctor (Miller and Weijer 2003). This rule applies to placebo-controlled trials in that it is only ethical to compare a potential new treatment with a placebo when there is no known effective treatment.

In the opinion of Lurie and Wolfe, the question that should have been asked was:

Can we reduce the duration of prophylactic [zidovudine] treatment without increasing the risk of perinatal transmission of HIV, that is, without compromising the demonstrated efficacy of the standard ACTG 076 [zidovudine] regimen? (Lurie and Wolfe 1997)

In response to this charge, Varmus and Satcher retorted that they were looking to answer a much more complex question than Lurie and Wolfe suggested. Their concern was not simply to establish whether a short course of treatment was better than nothing but also whether the short course was safe and if so whether the demonstrated efficacy compared to placebo was large enough to make it affordable to the governments in question. This viewpoint was supported by an internationally renowned South African HIV researcher who argued that the fundamental research question related to whether short courses of antiretrovirals could reduce vertical transmission sufficiently to warrant their wide-scale implementation in South Africa (Abdool Karim 1998).

Varmus and Satcher argued further that:

the most compelling reason to use a placebo controlled study is that it provides definitive answers to questions about the safety and value of an intervention in the setting where the study is performed, and these answers are the point of the research. (Varmus and Satcher 1997)

The investigators believed that two different populations were being studied, and it was not possible to extrapolate findings from the United States to Africa. The ACTG 076 regimen in the United States required that women receive HIV testing and counseling early in pregnancy, comply with oral treatment for several weeks and intravenous antiretroviral during labor, and refrain from breast-feeding. In addition, babies would have to receive six weeks of oral antiretrovirals. South Africa, in common with other developing countries, had a high frequency of home deliveries especially in rural communities (Abdool Karim 1998). In developing country settings, women present late for antenatal care have limited access to HIV testing and counseling and depend on breast-feeding to protect their babies from malnutrition and diarrheal diseases. The safety of zidovudine in populations who have a high incidence of malnutrition and anemia was unknown. The cost of the ACTG 076 regimen was approximately $800 per treatment, far in excess of the per capita health-care expenditure of under $10 in most developing countries (Varmus and Satcher 1997). Charges were also made that the critics’ commentary of the trials “reflects a lack of understanding of the realities of health care in developing countries” (Halsey et al. 1997).

The Utility Of Existing Data

There was disagreement on the use of observational or historical data to provide the same information that could be obtained from the placebo arm. Advocates of placebo-controlled trials and the WHO argued that “historical controls” were not reliable sources of data due to the change in vertical transmission rates from one country to another. Abdool Karim agreed and substantiated his claims with data from South Africa that indicated differences in vertical transmission rates from 1991 to 1994. He added that the vertical transmission rate is influenced by a number of factors including cesarean section rates, maternal viral load, and breast-feeding rates. As such, the use of historical controls would lead to spurious and hence unacceptable conclusions (Abdool Karim 1998).

Critics of the trials however believed that the differences between the ACTG 076 trial participants and those in sub-Saharan Africa were being exaggerated and that HIV vertical transmission rates were known in Africa and were in the region of 20–30 %, making the use of historical controls possible.

Equivalence Trial Issues

When effective treatment exists, a placebo may not be used, and subjects in the control group must be given the best known treatment (Angell 1997). Such a study is termed an equivalence study and the results are scientifically valid.

If the ACTG 076 regimen were used as the control group in the controversial vertical transmission trials, it would be termed an equivalence trial. Such a trial would be useful if it were proven that short-course treatment regimens were as good as or better than the ACTG 076 regimen. It is also necessary for the expected outcome of the control to be known. Abdool Karim argued that the effect of ACTG 076 in South Africa is not known and could not be extrapolated from other settings given the differences in breast-feeding rates, sexually transmitted disease rates, cesarean section rates, levels of viral load, and other variables.

Advocates of placebo-controlled trials held that equivalence trials required a much larger sample size to show a difference between two active arms of the study, and hence, they would take longer to complete and cost more. Furthermore, the larger numbers of participants would result in exposure of more people to the risk of research.

Ethical Dimension

The Guidelines

Critics of placebo-controlled trials argued that the trials violated principles enunciated in several major international ethics guidelines. The Declaration of Helsinki was exhaustively invoked. In support of her objections to the placebo controlled trials, Angell cited the following tenets of the DOH 1996:

In research on man, the interest of science and society should never take precedence over considerations related to the wellbeing of the subject.

and:

In any medical study, every patient – including those of a control group, if any – should be assured of the best proven diagnostic and therapeutic method. (WMA 1996)

Guidelines 8 and 15 of the WHO document – CIOMS (1993) – were frequently invoked.

Here, researchers were required to ensure, inter alia:

that persons in underdeveloped communities will not ordinarily be involved in research that could be carried out reasonably well in developed communities and that research was responsive to the health needs and priorities of the community in which it is to be carried out.

Guideline 15 stated that the proposed study should be submitted for ethical and scientific review, and the ethical standards applied “should be no less exacting than they would be” for research in the sponsoring country itself (CIOMS 1993).

Advocates of the placebo trials cited the principles of the Belmont Report. Emphasis was placed on the shift from the principle of beneficence to justice – equitable access to clinical trials (The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979). Guideline 8 of the CIOMS document relating to responsiveness to local needs in research conducted in developing nations was also cited. Hence the guidelines were used as ammunition to defend the positions of both proponents and critics of the placebo-controlled trials indicating the internal contradiction that exists in many international documents.

Standard Of Care

After the efficacy of the ACTG 076 regimen had been established in the United States in 1994, it became the “gold standard” in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Hence, both critics and proponents of placebo-controlled trials were in agreement that placebo-controlled trials could not be conducted in the United States. Critics of the trials argued for a universal standard of care irrespective of where in the world the research was being conducted.

Proponents however argued that participants in the control group would have received exactly the same standard of care if they had not participated in the trials – the local standard of care which at that time was no treatment in the developing world.

According to Marcia Angell, the justifications for these trials are:

reminiscent of those for the Tuskegee study: Women in the Third World would not receive antiretroviral treatment anyway, so the investigators are simply observing what would happen to the subjects’ infants if there were no study. And a placebo-controlled study is the fastest, most efficient way to obtain unambiguous information that will be of greatest value in the Third World. (Angell 1997)

Ethical Imperialism

Ethical universality refers to the belief that the ethical principles that guide the conduct of research are the same wherever in the world research is conducted. Ethical relativism refers to the belief that ethical principles that guide the conduct of research vary from one cultural setting to another. This concept is based on skepticism and tolerance. Skepticism refers to the belief that actions may be defined as right or wrong by specific people in specific cultural contexts at specific times. Hence behavior is culturally relative. Ethical relativity contends that the “impossibility of objectively determining moral action obliges tolerance toward other cultures” (Christakis 1996).

Hence in transcultural research, the ethical requirements of both cultures involved will need to be met. This approach is problematic in that a third cultural system could regard the two systems involved as unethical and there is no provision made for conflict resolution. Ethical pluralism on the other hand “acknowledges the key position of culture in shaping both the content and the form of ethical rules and it includes a mechanism of dispute resolution through mutual evaluation and negotiation” (Christakis 1996).

Critics of the placebo-controlled trials were accused of ethical imperialism – trying to impose their ethical standards on countries that had made their own judgments on the trials, based on their particular needs.

This debate predated the actual conduct of HIV vertical transmission trials. Marcia Angell, in 1988, raised the fundamental question of whether:

ethical standards are relative, to be weighed against competing claims and modified accordingly, or whether like scientific standards, they are absolute. (Angell 1988)

She argued then, as she did in 1997, that fundamental principles of humane research should not be compromised. She maintained that:

Subjects in any part of the world should be protected by an irreducible set of ethical standards, including the requirements that they not be subjected to unreasonable risks and that they be asked for informed consent to participate. (Angell 1988)

Local investigators, however, thought otherwise. Commentary from the Uganda Cancer Institute was as follows:

These are Ugandan studies conducted by Ugandan investigators on Ugandans.

The studies in Uganda had been approved by local ethics committees.

Dr. Nicolas Meda, an epidemiologist from Burkina Faso, argued that health research in poor countries should be designed and conducted pragmatically, in keeping with local health needs and priorities. In 2002, he addressed a conference of European medical ethicists and made the following statement:

Dogmatic interpretation of universal ethical principles in medical research will paralyse research efforts to improve HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa. (Richards 2002)

Marcia Angell argued that:

ethical imperialism obscured a more insidious danger to developing countries: ethical relativism, which opened the door to exploitation of the vulnerable peoples of the Third World.

Critics of the trials dismissed the charge of ethical imperialism and drew attention to the conflict of interest many investigators were in due to the substantial amount of research money at stake. Marcia Angell argued that researchers who levied charges of ethical imperialism against her were not necessarily advocates of the poor in their countries. Professor Hoosen Coovadia, one of the investigators involved in the Petra trials in South Africa, responded to her charge as follows:

In these debates it was implied that we are merely passive recipients of research plans devised in Europe or the USA. This is not so, and in many instances we actively seek assistance to pursue research ideas of importance to our people. Indeed, in South Africa the barren years of apartheid isolation have instilled in us a keen appreciation of international co-operation – the HIV projects are as much ours as they are the property of our international partners. We have demanding Ethics Committees in our Universities (the first was established at the University of Witwatersrand in 1966) and regularly updated guidelines on Ethics for Medical Research published by the Medical Research Council. Our research is therefore conducted in an environment where the protection of the individual and communities is safeguarded. The assertions by Angell, Lurie and Wolfe accordingly challenge our sovereignty in making and implementing our own decisions. (Coovadia and Rollins 1999)

The debate on ethical relativism versus ethical universalism was highlighted by the attempt to apply international declarations in various developing world settings in the context of HIV vertical transmission trials.

Justice

Grodin and Annas based their objections to the trials on the principle of justice. They argued that poor participants should not bear the burdens of research that they were not going to benefit from. It was clear at the time the trials were conducted that the Ministry of Health in South Africa was not going to sanction the provision of short-course antiretroviral treatment to pregnant women even if the trials did prove the treatment to be efficacious. His argument was underscored in Minister Zuma’s decision in 1998 not to provide the four-week course of treatment to pregnant women (Knox 1998). In retrospect, that was probably a good decision. After all, the four-week treatment regimen did not prove to be efficacious. However, the basic tenet of the argument remains valid – a protocol should contain a plan to implement results.

Vertical Transmission Trials In South Africa: The Results

Many of the arguments posed by both critics and advocates of the placebo-controlled vertical transmission trials were validated or rejected by the results of the trials in developing countries. I will focus my discussion on the results of the Petra trials that were conducted in South Africa, Uganda, and Tanzania between June 1996 and January 2000.

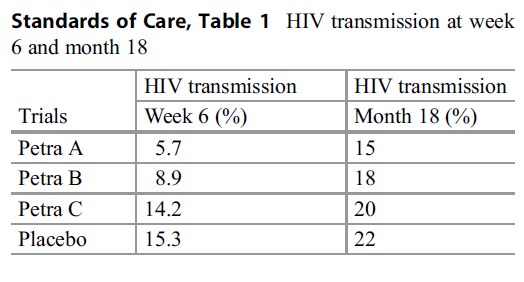

Table 1 HIV transmission at week

Table 1 HIV transmission at week

1457 HIV-positive pregnant women were randomized to one of four groups: A, B, C, or placebo. Groups A, B, and C had different shortcourse antiretroviral drug regimens. To facilitate

Standards of Care, ease of understanding of results, the HIV transmission rates in the various groups are presented in Table 1 at week six and month 18.

The results indicate that although regimens A and B were effective in reducing HIV transmission compared to placebo, this effect could not be sustained to 18 months. This can be attributed to the predominance of breast-feeding in these populations compared to the ACTG 076 regimen study population. The investigators in this study have justified the use of placebo on the basis of a difference in study populations. They also indicate that if a placebo group had not been used or if the ACTG 076 regimen was used instead of placebo, two errors in interpretation would have occurred. The Petra C regimen would have been considered to be effective and the degree of effectiveness of all three groups would have been overestimated (PetraStudyTeam 2002). Similar results were established in the HIVNET 012 study in Uganda where breast-feeding impacted on HIV transmission rates at 20 months but to a lesser extent (Guay et al. 1999).

ACTG 076 And The Vertical Transmission Trials

How do these results correlate with the criticism leveled against these trials in 1997?

The charge of lack of clinical equipoise cannot be substantiated. If there were no clinical equipoise, the short-course treatment would have been more effective than placebo – this was only the case for 6 months after the study was initiated. Follow-up to 18 months, however, revealed no statistically significant difference between treatment and placebo groups.

The reasons forwarded regarding the differences between the North American study population and the African study populations and uncertainty regarding how they would impact on also unjustified: there are two good scientific and statistical reasons why an equivalence trial would not have been feasible as discussed above. It is most likely that an equivalence trial would have shown that ACTG 076 was better than short course treatment. How would that have helped the HIV epidemic in South Africa? (Coovadia and Rollins 1999).

The principle of justice was not at issue – the Department of Health did not implement the short course treatment in 1998 – this has proved to be a good decision. The efficacy of the short-course regimen compared to placebo was not large enough to make it affordable to the South African government. When nevirapine was shown to be effective in the HIVNET 012 trials in Uganda at a fraction of the cost of other short-course regimens, treatment for pregnant women was made available in South Africa (Guay et al. 1999).

The charge leveled against critics of the placebo trials was that they were ill informed regarding health-care and research priorities in developing countries, and this appeared to be the case as was reflected in the outcome of these studies.

Finally, it appears as if the charges of ethical imperialism leveled at Angell, Lurie, and Wolfe by developing world researchers were justified, and the results of the study serve to prove that.

Tuskegee Revisited

In the course of the debates surrounding the HIV vertical transmission trials, the justification presented for use of a placebo arm was the fact that the women on the placebo arm would have received no treatment (which was the standard of care in developing countries) in the absence of the clinical trial. Marcia Angell, in her critique of the use of a placebo arm in the trials, drew the following comparison to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study:

The justifications are reminiscent of those for the Tuskegee study: Women in the Third World would not receive antiretroviral treatment anyway, so the investigators are simply observing what would happen to the subjects’ infants if there were no study.

This comparison has been challenged by the investigators involved as well as by Fairchild and Bayer. Fairchild outlines the three features in the Tuskegee study that characterize the consistent research abuses that occurred:

First, the study involved deceptions regarding the very existence and nature of the inquiry into which individuals were lured. As such it deprived those seeking care of the right to choose whether or not to serve as research subjects. Second, it entailed an exploitation of social vulnerability to recruit and retain research subjects. Third, Tuskegee researchers made a willful effort to deprive subjects of access to appropriate and available medical care as a way of furthering the study’s goals. (Fairchild and Bayer 1999)

She objects to the analogy drawn in the context of the vertical transmission trials as “investigators clearly made efforts to inform the enrolled women that they would be part of a study to reduce maternal transmission” and that some would receive placebo.

The nature of consent obtained from study participants had however been challenged by researchers working in Thailand and South Africa.

In 1998, attention was drawn to the informed consent documents used in Thailand. Discrepancies were noted in the Thai and English versions of the documents. The Thai version described the placebo as a “comparison drug that does not contain zidovudine,” while the English version described the placebo as an “inactive substance” which was “like a sugar pill.” The Thai critics charged that the words “inactive substance,” “placebo,” and “sugar pill” did not appear in the Thai documents even though Thai words or concepts did exist for these words (Achrekar and Gupta 1998, pp. 1331–1332).

In South Africa, contention was also raised by the use of the word “chuff-chuff” drug which means “pretend drug” and “spaza” drug which alludes to “half the real thing” in colloquial terms. While “chuff-chuff” drug is acceptable, “spaza” drug is misleading (Prabhakaran 1997).

Even though these controversies did exist regarding the content of informed consent documents used in the HIV trials, an informed consent process was followed in all the trials conducted in developing countries, some better than others. In no way did the HIV trials bear any resemblance to the Tuskegee study where there was an absence of the informed consent process altogether.

Fairchild goes on to contend that the social vulnerability of the women involved was not exploited. On this claim I will argue that these were vulnerable women. The UNAIDS definition of vulnerable communities includes communities with:

- Limited economic development

- Inadequate human rights protection and discrimination based on health status

- Inadequate understanding of scientific research

- Limited health-care and treatment options

- Limited ability to provide individual informed consent

The black women enrolled in the trials in South Africa definitely shared a social and economic vulnerability with the African-American men in the Tuskegee study. To the extent that this study would not have been approved in the United States on American women, an exploitation of their vulnerability cannot be denied.

However, the placebo group served only as a comparison arm for the short course, potentially more affordable regimen being tested. Tuskegee was an observational study where all participants were deprived of affordable treatment. In the HIV trials women in the placebo group were deprived of treatment that was locally both unavailable and unaffordable. In this respect, an analogy with Tuskegee cannot be drawn. Furthermore, Benatar argues that the analogy:

minimises the deception, maleficence, paternalism, lack of accountability, racism and gross exploitation demonstrated by the researchers in the Tuskegee study. The analogy serves to trivialize Tuskegee. (Benatar 1998)

Revision Of Guidance

Declaration Of Helsinki 2000

As a result of the international concern evoked by the placebo debate, an attempt was made to amend the 1996 version of the Declaration of Helsinki. A proposal was made to change the specification on treatment for control groups in the 1996 version from:

In any medical study, every patient – including those of a control group, if any – should be assured of the best proven diagnostic and therapeutic method.

to:

In any biomedical research protocol, every patient subject, including those of a control group, if any, should be assured that he or she will not be denied access to the best proven diagnostic, prophylactic or therapeutic method that would otherwise be available to him or her.. . .When the outcomes are neither death nor disability, placebo or other no-treatment controls may be justified on the basis of their efficiency.

This revision was open for comment and a second debate ensued. Those who objected to the change feared that the changes would weaken the principles of the declaration:

these revisions may inappropriately cause a shift to an efficiency-based standard for research involving human subjects and weaken the principles of the investigator’s moral commitment to the research subject and the just allocation of the benefits and burdens of research, which have heretofore been the hallmarks of ethical research. The revisions will also logically lead to an explosion of research in developing countries that would be intended mainly to benefit developed countries – another affront to current notions of ethical research. (Brennan 1999)

The change to “best available” could not be implemented in the face of the strong criticism leveled against the World Medical Association. Ultimately, the change to “best current” treatment for the control group was implemented in the 2000 version.

CIOMS 2002

While the 1993 version did not include a guideline on standard of care, the 2002 version added this consideration in Guideline 11:

As a general rule, research subjects in the control group of a trial of a diagnostic, therapeutic or preventive intervention should receive an established effective intervention. In some circumstances, it may be ethically acceptable to use an alternative comparator, such as placebo or no treatment.

There is no elaboration on “established effective” intervention – is this established globally or locally in the developing country?

Conclusion

While these major revisions were undertaken by the World Medical Association and the World Health Organization in response to the placebo debate, commentators started to question the basis for making such sweeping changes. It was charged that “tough cases make bad law,” so was it valid to generalize from the placebo trials? After all the HIV vertical transmission case study had unique features – these were trials on pregnant women where placebo use meant passively allowing transmission to infants. In many cases the risk calculations in using placebo were doubled by this situation alone. It was argued that using this case study as a precedent to make revisions in guidelines that affect all research would not be valid (Brennan 1999).

The validity of this comment has been borne out in the numerous footnotes that have been added to the Declaration of Helsinki since 2000 to avoid generalization and ultimately to encourage case-by-case decisions on the use of placebo.

The revisions of both these international documents providing guidance in human participant protection evoked unprecedented attention in research ethics circles, among REC members and investigators alike. This occurred in developed and developing countries alike. Today all RECs are sensitive to standards of care used in control groups in randomized controlled clinical trials. Placebo-controlled trials are approved only where adequately justified and indicated.

Bibliography :

- Abdool Karim, S. S. (1998). Placebo controls in HIV perinatal transmission trials: A South African’s viewpoint. American Journal of Public Health, 88(4), 564–566.

- Achrekar, A., & Gupta, R. (1998). Informed consent for a clinical trial in Thailand. New England Journal of Medicine, 339, 1331–1332.

- Angell, M. (1988). Ethical imperialism? Ethics in international collaborative clinical research. New England Journal of Medicine, 319(16), 1081–1083.

- Angell, M. (1997). The ethics of clinical research in the third world. New England Journal of Medicine, 337, 847–849.

- Christakis, N. A. (1996). The distinction between ethical pluralism and ethical relativism: Implications for the conduct of transcultural clinical research. In H. Y. Vanderpool (Ed.), The ethics of research involving human subjects (pp. 261–278). Frederick: University Publishing Group.

- (1993) International ethical guidelines for bio-medical research involving human subjects. Geneva, Switzerland: Council of International Organisations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS).

- (2002) International ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects. Geneva, Switzerland: Council of International Organisations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS).

- Connor, E. M., Sperling, R. S., Gelber, R., Kiselev, P., Scott, G., et al. (1994). Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. New England Journal of Medicine, 331, 1173–1180.

- Coovadia, H. M., & Rollins, N. C. (1999). Current controversies in the perinatal transmission of HIV in developing countries. Seminars in Neonatology, 4, 193–200.

- Fairchild, A. L., & Bayer, R. (1999). Uses and abuses of Tuskegee. Science, 284, 919–921.

- Guay, L. A., Musoke, P., Fleming, T., et al. (1999). Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to child transmission of Hiv-1 in Kampala, Uganda:Hiv-1net 012 randomised trial. The Lancet, 354, 795–802.

- Petra Study Team. (2002). Efficacy of three short-course regimens of zidovudine and lamivudine in preventing early and late transmission of HIV-1 from Mother to Child in Tanzania, South Africa, and Uganda (Petra Study): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet, 359, 1178–86.

- Richards, T. (2002). Developed countries should not impose ethics on other countries. BMJ, 325, 796.

- The National Commission for the protection of human subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research. (1979) The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, OPRR Reports.

- Varmus, H., & Satcher, D. (1997). Ethical complexities of conducting research in developing countries. NEJM, 337, 1003–1006.

- World Medical Association. (1996). Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Geneva, Switzerland: World Medical Association.

- World Medical Association. (2000). Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Geneva, Switzerland: World Medical Association.

- Benatar, S. R. (1998). Global disparities in health and human rights: A critical commentary. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 295–300.

- Brennan, T. A. (1999). Proposed revisions to the declaration of Helsinki – Will they weaken the ethical principles. NEJM, 341, 527–531.

- Prabhakaran, S. (1997). Mothers give support to placebo trials. Mail and Guardian: Page 5.

- World Medical Association. (2000). Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Geneva: World Medical Association.

- Halsey, N. A., Sommer, A., Henderson, D. A., & Black, R. E. (1997). Ethics and international research. BMJ, 315, 965–966.

- Knox, R. (1998). Despite epidemic, South Africa cuts AZT project. Boston Globe 1: A17.

- Lindsey, J. C., Shah, S. K., Siberry, G. K., Jean-Phillipe, P., & Levin, M. J. (2013). Ethical tradeoffs in trial design: Case study of an HPV vaccine trial in HIV-infected adolescent girls in lower income settings. Developing World Bioethics, 13(2), 95–104.

- Lurie, P., & Wolfe, S. M. (1997). Unethical trials of interventions to reduce perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in developing countries. New England Journal of Medicine, 337(12), 853–855.

- Miller, P. B., & Weijer, C. (2003). Rehabilitating equipoise. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 13(2), 93–118.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.