This sample Substance Abuse Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Abstract

Psychotropic substances were used throughout history for medicinal, ritual, and recreational purposes. Overuse may result in pathological consumption styles, mainly dependence and other forms of abuse (hazardous use, harmful use). Attempts at political, religious, and social control of use, including total prohibition of all or specific substances, show mixed success. While traditional use and experimental use mostly have a sociocultural background, dependence and other forms of abuse are classified as a behavioral pathology and as medical conditions. Different ethical aspects and rules apply for use, nondependent abuse, and dependence, respectively. Human rights and medical ethics provide a framework of consequential ethics. Interventions for abuse, their organization, and performance are discussed in some detail, and special attention is paid to the vulnerabilities (stigmatization, marginalization, comorbidities) of people with addictive behavior.

Introduction

Substance abuse is one of the major health and social problems at global level, in spite of all efforts to curb extent and ensuing damage. Alcohol and tobacco rank highest of all psychotropic substances as contributors to the global burden of disease (Murray and Lopez 1997). An estimated 166–324 million people have used an illicit drug in 2012, and 18–39 million are abusers (UNODC 2015).

The relevant UN Organizations recognize substance abuse as a medical condition for which evidence-based preventive and therapeutic interventions exist. The implementation of the respective services and professional education is far from satisfactory. Only one of six dependent users in need of treatment receives it; even more alarming is the low access of imprisoned drug users to appropriate treatment (UNODC 2015). The principles and rules of medical ethics are often overruled by other interests, moral prejudice, and discrimination. Enormous efforts at all levels are at stake for improving effective and ethically acceptable care for substance abuse.

Substance Use And Abuse History

Use came before abuse. Psychotropic substances have been used throughout the history of mankind, starting with the knowledge of plants and their effects in the age of hunters and gatherers. The observation of fermented fruit and the production of alcoholic beverages started well before the 5th Millennium B.C., for nutrition and ritual purposes. Among the first documented in history are also opiates, detected in human dwellings from the 3rd Millennium B.C. Alcohol, opium, cannabis, coca, and tobacco have a long history of medicinal use, as universal or especially for analgesia. Other therapeutically/ritually used drugs are hallucinogenic substances, khat and kava.

Problematic effects of use must have been observed early on, and we have relevant documents on such observations since antiquity. Problematic effects may explain the development of consumption control strategies, including privileged access (e.g., coca for the ruling class in Inca culture, hallucinogenic drugs for initiates only in Greek secret societies, wine for nobility over centuries, rationing schemes, use of drugs at specific events only). Ritualistic arrangements allowed use without excessive use. Main control strategies came from political and religious authorities. The notion of substance use and misuse as a moral weakness grew on the basis of a religious ideal of moderation or abstinence from pleasure-seeking behavior. It was a reaction to abundant substance use and its negative consequences. In medieval Europe, restrictive alcohol use was imposed after the deadly epidemic of plague. Alcohol and drugs are banished in Islam; alcohol prohibition existed from 1919 to1933 in the USA. Rationing schemes are known for opium in Middle East countries, for alcohol in Sweden. Other strategies were implemented by civil societies (temperance movements) since the eighteenth century, when the mass production and consumption of spirits created major social problems across all strata of society and threatened the increasing economic competition and the demand for efficient management. Finally, the extraction of active substances from the natural products – morphine and cocaine – and their use in patent medicines in late nineteenth century, as well as the invention of parenteral injection, led to an enormous increase in consumption. This prepared the ground for legal measures in order to curb the extent of abuse, on national and international levels (Harrison Act in 1914 in the USA, International Opium Convention in 1912, UN conventions on narcotic drugs in 1961, 1971, 1988).

All these efforts to control use and abuse of addictive substances did not primarily focus on the individual, but on society or on specific strata of society, in the interest of public health and public order. The concepts of “abuse,” dependence, and addiction however developed in the medical field, based on observations of patients suffering from negative consequences of their habit. Alcoholism was described as a medical condition in the course of the nineteenth century, followed by morphinism and cocainism. Various terms were used for a similar clinical syndrome, while the concept oscillated between a physiological illness, a mental condition, and a learned misbehavior. Therapeutic regimes of addicted patients evolved. An abstinence regime was introduced and recommended when the condition was attributed to the effects of the substance, without regard to environmental and personality factors. Psychotherapy, milieu therapy, and spiritual interventions grew on the respective beliefs about the relevant cause of addiction.

Conceptual Clarification/Definition

Current Diagnostic Criteria

The medical concepts of substance abuse and dependence define those as disorders, comparable to other medical conditions, with specific symptoms; with somatic, psychological, and social risks; and with evaluated therapeutic approaches. This is in contrast to other interpretations of addictive behavior, mainly a moral understanding (weakness of will, undisciplined pleasure seeking, egotistic neglect of social obligations, etc.). Such moralistic attitudes are widespread, stigmatizing addicted persons and impeding their treatment. Another complication comes from legal prohibition, when substance use and abuse are considered criminal acts that must be punished.

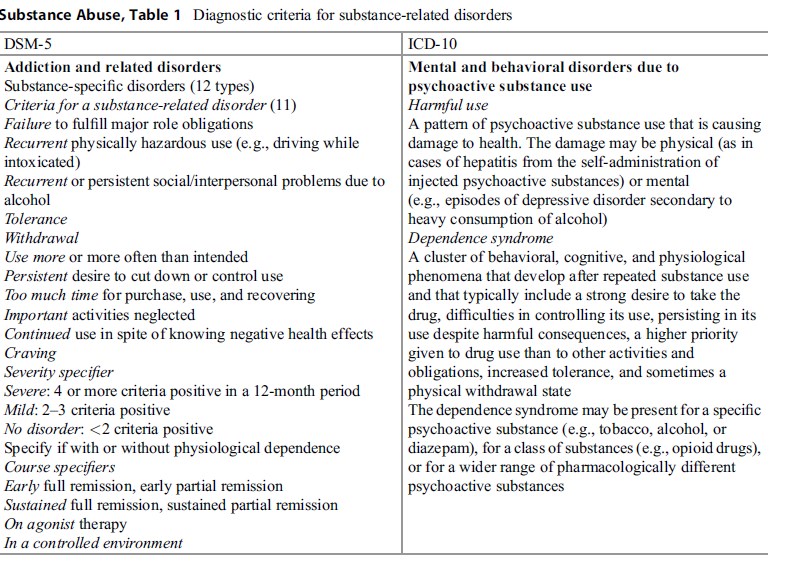

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for substance-related disorders

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for substance-related disorders

The current diagnostic definitions are part of the International Classification of Diseases by World Health Organization, 10th edition (WHO 1990), and of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, 5th edition (APA 2013). Those definitions use different terms and specifications (Table 1). This limits the comparability in substance abuse research, as well as the communication on clinical and public health issues in substance abuse.

The criteria in both diagnostic systems are heterogeneous: some physiological (tolerance, withdrawal), some psychological (craving, desire to stop or reduce consumption, loss of control), or social (neglecting other activities). For determining a diagnosis, only some of the criteria are to be met; consequently, patients with the same diagnosis present heterogeneous clusters of criteria. Criteria are valid for all types of substances, but have not the same weight for all substances. Finally, the various addictive substances differ widely in their risk profiles, and therefore the term substance abuse covers a range of substance-specific issues.

Many of these criteria apply also to other human behavior. Withdrawal, neglect of other activities, and continuation despite problematic consequences may apply to “workaholics” or excessive sexual appetite, but we value it quite different from our value judgment on substance abuse and dependence.

In the following, the term of substance abuse has the meaning of any kind of hazardous, harmful, or pathological substance consumption, substance dependence being a specified type of abuse. Problem drug use is about the same as abuse; addiction is a synonym of dependence.

Addiction Theory

The diagnostic systems are essentially descriptive, avoiding causal factors for the definition of disorders. They do not explain how and why addictive behavior happens. In contrast, the present understanding of substance abuse and addictive behavior in general (including syndromes of nonchemical dependence) focuses on brain research, epidemiology and clinical studies on personality factors, prognosis, and treatment outcome.

Based on the development of brain imaging techniques in vivo, an enormous amount of knowledge accumulated on functional processes as effects of substances of abuse, as well as on the structure of the cerebral reward system and its transmitters, and on structural changes after continued use of such substances (Volkow et al. 2003).

Epidemiological surveys provide knowledge on incidence and prevalence rates of substance use and related disorders, on how substances are used, by whom, and with what kind of consequences; repeated surveys can tell us about changes over time. Knowledge on the social conditions that shape addictive behavior and on the role of interventions at population level stems from this type of research (WHO 2002).

Patient observation and clinical research provides knowledge on personality factors and psychological processes involved in addictive behavior, as well as on the value and limitations of therapeutic interventions at individual level.

Neither of these research-based theories is sufficient to explain addiction. Theory of addiction at its best makes an effort to bring these different types of knowledge together and to consider their interactions and complimentary value rather than opposing them. A prominent example is the volume by Robert West (West 2006), presenting a comprehensive research-based framework of motivational processes as a basis for human behavior. In general, there is some consensus in the scientific community about the diversity of factors – somatic, psychological, environmental – contributing to the development of substance abuse. The most popular underlying concept is the biopsychosocial model of George Engel that stresses the need for an interdisciplinary approach in dealing with most psychiatric conditions including addictive disorders.

Different types of explanation are valuable for specific phases in the development of addiction. Starting the use of addictive substances is mainly fostered by milieu factors, social conditions, peer influence, self-regulation/self-medication to counteract unpleasant states of mind, and certain personality traits such as sensation seeking. The passage from occasional to regular use, including hazardous and harmful use, is facilitated by a trend to optimize performance (neuroenhancement), by successful self-regulation, but also by a deficit in other forms of pleasurable experiences. Developing dependence finally is facilitated by genetic vulnerability and exposure to chronic stress (internal or external).

The very nature of dependence is far from being universally accepted. On the one hand, dependence is considered a chronic, relapsing condition; on the other side, the majority of persons with substance dependence recover without formal or therapeutic interventions. The lessons to be learned from “natural recovery” include the role of life events and of social support for successful and persistent behavior change from dependent use to moderate use or abstinence.

Ethical Dimension

Ethical aspects of substance abuse cover a range of issues: the ethics of substance use as well as of abuse, in an individual and in a societal perspective. They need a separate discussion. The common framework is the concept of consequential ethics.

Basic Orientation: Consequential Ethics

The philosophical debate includes a distinction between absolutist and utilitarian positions. Absolutism means the acceptance of a conduct code based on absolute, indisputable rights and duties (e.g., abstaining from substance use). Utilitarianism has its focus on the consequences, not on the reasons or motives of conduct; whatever the motives are, moral judgment is based on the consequences of behavior (e.g., of substance use). This utility principle has a long-standing tradition in various forms. A most prominent representative was the English philosopher John Stuart Mill; a contemporary representative of a consequential ethics is Hans Jonas.

The absolutist position states: “Right is to be done come what will come. I am not answerable for the consequences of doing right, only of not doing it.” The utilitarian position is summed up by “success is the touchstone; the might of obtaining the reward.” Examples of absolutist positions are the categorical demand for abstinence from all or specific addictive substances or the claim for complete individual responsibility in using such substances without interference by others. A utilitarian position however cares about the consequences of use as well as of any interventions against substance use and abuse, in general and under specific sociocultural conditions.

Ethical Aspects of Substance Use

Acceptability of substance use depends on the acceptability of the consequences of use. Consequential ethics must value the outcome of substance use for individuals and for society.

The risk profile of specific substances should be known and respected. The Global Burden of Disease Study of World Health Organization documents the prominent role of legal substances (alcohol and tobacco) for health problems at the population level, and a recent summary describes the extent of addictive behaviors globally (Gowing et al. 2015). Ratings of substances according to their harm profile are available (Van Amsterdam et al. 2015).

The harm profile has not consistently guided drug policies and the ethical debate. Alcohol, in spite of its high-ranking position concerning harms, has received some attention in terms of harm prevention, but public opinion and policies are reluctant to envisage effective strategies to curb consumption. This is due to long-standing cultural traditions, to economic considerations, and to the influence of a powerful industry profiting from extensive consumption. On the other side, the prohibition of substances with a much lower rating for harm (e.g., cannabis or ecstasy) does not respond to a consistent policy orientation of harm avoidance, but to other political considerations. These are examples of ethical conflict, weighing the potential and effective harm of a specific substance against other societal values. A cultural embedding of use in a long-standing tradition favors acceptability of use in spite of major harm, while foreign origin of “newcomers” in the drug spectrum favors repression.

Apart from these culture-specific aspects, the ethical debate also knows some global arguments concerning individual and societal values. At the individual level, the main values at stake are the demand for self-fulfillment (developing the personal talents and potentials), self-responsibility (managing one’s own life with sensible goals and decisions), and self-control (limitation of pleasure-seeking behavior). At the societal level, the values at stake are the fulfillment of citizen’s obligations (for one’s own sustenance and for the functioning of the community), maintenance of public safety and public order, and the sociocultural acceptability of behavior. For all these, the use of addictive substances may have consequences, and acceptability is linked to the extent of negative effects of use.

Ethical Aspects Of Nondependent Substance Abuse

The ethical aspects of nondependent abuse (hazardous use, high-risk use, harmful use without meeting the criteria for dependence) must be discussed separately from those of dependent use. Nondependent abuse has its roots in sociocultural conditions, in learned behavior, in the characteristics of a given professional or family milieu, and in a person’s attitudes, and it is not generally understood to be a medical condition in the same sense as dependence. Nevertheless, nondependent abuse is included in the diagnostic schemes (per se or as a less severe form of abuse) and is frequently diagnosed in medical practice. Specific interventions (brief interventions, early interventions, motivational interviewing) are available and applicable wherever nondependent abuse is seen (in medical and social services, by police, in clubs, etc.). They are evaluated to be effective. The professional ethics of those dealing with nondependent abusers apply; there are no universal rules to observe.

However, nondependent abuse precedes dependent abuse, and hence, interventions against the social factors fostering substance abuse are an essential instrument to reduce dependence. According to epidemiological research, economic inequality, illiteracy, misguided urbanization, and loss of social traditions and networks are important causal factors for substance abuse globally (WHO 2002). In order to achieve the WHO goal “health for all,” the scope of activities must include interventions securing the conditions for health protection. Great efforts are necessary on all levels, national and international; in legislation; in health policy; in the education of all concerned professionals; and in service provision in order to reduce incidence and prevalence rates of drug abuse.

Ethical Aspects Of Substance Dependence

Which Ethics Apply?

Today’s drug policy claims to be evidence based. Evidence means that policy recommendations follow scientific findings on “what works” and therefore have a good chance to lead to positive results. Drug policy is based on principles of consequential ethics. But what are the goals? We have to deal here with the criteria of the human rights declaration as a general framework and with the principles of medical ethics that must fully apply when dealing with substance abuse. Will they allow us an ethical judgment on the results of treatment as well as on the consequences of treatment policy?

Human rights: The principles of human rights apply to all human beings. Most states have signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN 1948). The Universal Declaration promotes a number of relevant conditions:

– No discrimination (art.2).

– No degrading or inhuman treatment (art.5).

– Right of equal access to medical care and social services (art.25/1).

– Everyone has duties to the community (art.29/1).

– Limitation of rights and freedom are admissible on the basis of “just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare” (art.29/2).

The European Convention on Human Rights (Council of Europe 1950) further stipulates that a person’s liberty may be deprived in case of lawful detention of alcoholics or drug addicts (art.5/1/e), with a right to appeal to a court (art.5/4).

These statements try to establish a balance between protecting the individual rights of the person and respecting the needs of society for public order, general welfare, and even morality. There is large room for interpretation, so that every society can decide on the compatibility of addictive behavior with the nature and extent of these requirements. Compulsory measures against persons with substance dependence may be admissible by national law. Therefore, human rights are no universally accepted basis for dealing with substance dependence.

Medical ethics. More to the point are medical ethics, as far as substance dependence and all types of substance-related conditions are accepted to be medical conditions. Substance dependent persons are patients and should enjoy the status and rights of patients in general. Principles of medical ethics apply in all matters of diagnosis, treatment, research, staff attitudes, service provision, and health policy.

However relevant the medical ethics are, they are not sufficient to cover all aspects of substance dependence. This is the basis of two controversies: the so-called medicalization of a social problem and the fight of medical versus moral treatment. Treating patients without regard to the social factors (at individual and population level) that facilitate incidence and prevalence of medical conditions is a misconception; Public health is a concept based on the necessity to care for the social conditions of illnesses. The basic S ambivalence – substance dependence as a medical condition or a moral weakness – is reflected in the opposition of medical and moral treatment. If moral treatment is understood to be educational and admonishing, this approach is nowadays widely replaced by an approach to help the addict in getting motivated for behavior change, by appropriate empathy, information, social, and moral support.

Medical Ethics: General Rules

The general ethical rules for good medical practice apply. The so-called oath of Hippocrates stated already to respect the patient’s well-being as the highest value in medicine and to respect the principle of the medical secret perpetually. A modern form of doctor’s obligation is the “Declaration of Geneva” of 1948 by the World Medical Association. It states that “the health of my patient will be my first consideration.”

Other sources on medical ethics are national conventions; examples are the Standards of Conduct of the American Medical Association and the Good Medical Practice of the English General Medical Council. Main issues are the patient’s autonomy of decision, informed consent, dignity and confidentiality, nondiscriminatory beneficence, and nonmaleficence, but also keeping up professional standards by continued education and networking with other services and colleagues in order to provide the best possible care. The American recommendations also include a responsibility to seek change in official or legal requirements that are contrary to the best interests of the patient. These codes usually acknowledge the occurrence of ethical conflicts and provide links for support in such cases.

Specific Ethical Rules For Substance Abuse Patients

It is obvious that even these few principles cannot be followed without creating conflict. Imminent risks from intoxication and risks of chronic self-damage invite measures to avoid causing harm to the abuser and to improving his/her well-being. What if the abuser does not comply? Involuntary intervention to prevent harm for the abuser as well as for other persons is in conflict with the autonomy of an unwilling patient. Treating all abusers as being equal is difficult when following the lessons from evidence-based guidance for interventions. The protection of sensitive data in the interest of substance abusers is often in conflict with administrative and law enforcement interests in case of illicit drug use or risks for others.

Such conflicts must be carefully examined, in the best interest of all concerned. Some rules on how to deal with conflicts apply. When the patient’s interests collide with those of relatives or other third parties, mediation must take place for a common solution. It is advisable to recur to an ethical cons ilium (second opinion from an expert) if major consequences are expected from a contested decision. In general, the principle of respecting the autonomy of the patient must never be overruled in the name of some abstract societal value without the presence of concrete harm implications for others.

Conflicting interests and guidance on how to proceed in such conflicts differ according to the type of intervention at stake. We must therefore discuss the main ethical aspects of the various intervention types and consider empirical evidence on outcomes of interventions, in order to satisfy the expectations of a consequential ethics.

Diagnostic Approaches And Procedures

All interventions must be based on a proper diagnosis. This is one of the main basic rules since antiquity. Contemporary medicine has a range of diagnostic tools and techniques that require the informed consent of a patient. Consultation of former medical documents and observations also requires consent. Any diagnostic intervention without informed consent is only admissible if the results are expected to be of relevant practical value for therapeutic planning or for forensic purposes (e.g., in emergencies and in criminal investigations). A diagnosis of addictive behavior has a stigmatizing effect, often with far-reaching consequences. Keeping the medical secret is essential, but often in conflict with the interests of employers, relatives, or others. Specific problems arise if illegal substances are involved or in specific situations (e.g., roadside examination when driving under the influence of addictive substances is suspected).

Targeted Prevention

Universal prevention against substance use and abuse is guided by sociocultural beliefs and increasingly by evidence-based strategies having the intended effects. Targeted prevention is directed toward persons with a high risk to develop addictive behavior (selective prevention) or showing first signs of such behavior (indicated prevention). These types of preventive action have a labeling effect on the targeted persons. Stigma and discrimination even marginalization are the inherent risks of such actions. If applied without informed consent, they create an ethical problem, even more so in the case of adolescents when parents are involved.

The touchstone is the effectiveness of targeted preventive actions. Weighing the risk of stigmatization against the probability of attaining the intended effects is inevitable. The situation is even more difficult if there is no evidence yet on effectiveness of planned actions.

Targeted action against risk factors, e.g., against adverse childhood experiences, shifts the risks of stigmatization from the child or adolescent to parents and families, and the basic problem with weighing the risks against (proven or unproven) effectiveness is the same. There is no easy solution to the conflict. The easiest cases are individuals or families where stigmatization and marginalization already are present. If not, interventions must be designed in a way that minimizes the negative effects. This effort needs more attention in the future.

Therapeutic Interventions

A hierarchy of objectives. The goals of treatments in substance dependence have changed over the last decades. Traditionally, abstinence was on top of the list. At present, the primary goal is the patients survival, followed by health improvements (or at least avoidance of deterioration), by improvements in social integration, by reductions in substance use (moving away from addictive behavior), and by improvements in quality of life (as defined subjectively by the patient), ultimately resulting in a responsible and satisfactory lifestyle. Abstinence is not conditional for reaching these objectives, nor does abstinence guarantee to reach them.

Tailoring treatment to individual needs. In view of the diversity of etiology, symptoms, and stages in substance dependence, treatment cannot be uniform for all dependent persons. Treatment needs differ between age groups and among other target groups (gender, ethnicity, comorbidity). Treatment must respond to the specific needs of an individual patient on the basis of a comprehensive needs assessment and a treatment planning process where patient and therapist work together on a shared understanding of what is needed and what should be done. Needs-based treatment has better outcomes in comparison to standardized programs, and even a careful assessment of individual needs at entry is gratified by better outcomes. Covering the needs for psychiatric care and living conditions (housing, jobs) is especially important for facilitating a reduction in substance use. “The combination of treatment components and services to be employed must be tailored to meet the needs of the individual, including where he or she is in the recovery process” is therefore one of the principles of addiction treatment (NIDA 2008).

Current Treatment Guidance

Therapeutic approaches and methods cover a large spectrum of pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, and psychosocial interventions. Evaluation efforts have accumulated an increasing body of research evidence on effectiveness and effectivity. Rigorous reviews and meta-analysis of the evidence (e.g., by the Cochrane Collaboration and the Campbell Collaboration), as well as advancements in research methodology (consensus on grades of evidence, on statistical analyses, on qualitative research), are the basis of evidence based comprehensive guidelines for treatment. In addition, general principles of substance abuse treatment were developed (NIDA 2008). The ethical standard of treatment depends on a good knowledge and rigorous application of this evidence based guidance.

In addition, service requirements include procedural rules and standards of infrastructure. Excluding patients on the basis of their religious or ethnic affiliation is not admissible. Services must assess and respond to all needs of patients, within their organization or by networking with other services. Special attention must be paid to the care of patients suffering from somatic and/or psychiatric comorbidities. Informed consent for all procedures and confidentiality must be standard, as well as nondiscriminatory attitudes and professional competence. Safety and hygiene of premises are essential. Services are accountable to patients, third parties, and the community served.

Substitution Therapies

A special approach is available for selected types of substance dependence. The famous physician Galen prescribed opium to an opium-addicted Roman emperor. Heroin prescribing is British practice since 1920, experimentation with morphine occurred in the USA and other countries, and replacement therapies started in Canada and in the USA in the 1960s. The main objective was to avoid excessive use as well as withdrawal syndromes, by implementing a regime of externally controlled use for those who had lost control over their consumption.

Today, the most prominent and well researched example is the opioid maintenance therapy (OMT) for heroin-dependent persons, replacing illegal opiates by agonist medications (methadone, morphine, pharmaceutical heroin) or medications with agonist/antagonist properties (buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone). In contrast to the traditional British practice to hand our opiate prescriptions, the prevailing practice today is a supervised intake of medication, in the framework of a comprehensive assessment and therapeutic program. In its review of the evidence, World Health Organization concluded that OMT is the most beneficial treatment approach to heroin dependence and made detailed recommendations on its implementation (WHO 2009). The benefits go beyond the avoidance of the risks in uncontrolled opioid use, providing substantial chances for improvements in health and social integration. However, OMT still meets severe restrictions or even strong opposition in a number of countries.

Another example is the replacement of smoked tobacco by nicotine patches, chewing gums, or non-smokable tobacco. The main objective here is to avoid the cancer genic properties of tobacco smoke. This type of substitution is rather harm reduction than treatment.

Harm Reduction Approaches

Harm reduction includes all interventions designed to protect or improve the health and social status of chronic addicts who are unable or unwilling to discontinue their addictive behavior. The range of interventions include:

– Needle and syringe availability for drug injectors (to prevent HIV infection through contaminated syringes)

– Safe consumption rooms (to prevent fatal over-dose and to provide medical and social care)

– Provision of opiate antagonists to families and peers of opiate injectors (to prevent fatal overdose by emergency medication)

– Drug testing and counseling in nightlife recreational substance use (to prevent harm from unknown substances)

The ethical debate on treatment and harm reduction is often a debate on opposing principles of action. In this debate, harm reduction is disqualified as an approach to prolong dependence, to make substance use acceptable for young people, and to undermine the readiness of addicts for treatment. None of these concerns were substantiated in research, and evaluation resulted in accumulated evidence for good goal attainment of the various approaches (Rhodes and Hedrich 2010). Today, harm reduction is considered an ally rather than an opponent of treatment.

Rehabilitation And Recovery

Substance dependence develops frequently on the background of social and personality factors that make it difficult to conduct a satisfactory life; it also leads frequently to a deterioration of life conditions. Treatment and care cannot be restricted to a reduction of addictive behavior. Patients should be helped to conduct a subjectively satisfactory life in the community. This includes specific rehabilitation efforts, programs, and services, such as supplementary education, vocational training, supported employment, housing, financial, and legal support. A recent movement under the label recovery calls for intensified efforts to rehabilitate addicted patients and enable them to become model citizens.

In an ethical perspective, it is essential to respect the individual potential and the subjective readiness of patients to engage in such a process.

Appropriate assessment of a person’s motivation, realistic opportunities, and available options is more acceptable and efficient than imposing a program and a standard that does not respond to the patient’s preferences . Refusing the demands of rehabilitation and recovery is a right to be respected, and a new kind of stigmatization for those who prefer to have their own ways (as far as compatible with the rights of others) must be avoided.

Coercive Care

As in psychiatry and in the case of dangerous contagious diseases, there are legitimate boundaries to the liberties of addicted persons, on the basis of rightful respect for the interests of others. Nonvoluntary hospitalization and treatment without informed consent is ethically acceptable, if no other measures are in place to protect a person from self-harm or others from the person’s harmful behavior. The rules to be followed in such situations concern a clear responsibility, eventually shared decision making, a careful documentation of reasons, and extent of the measures taken.

Using nonvoluntary confinement and regimes in order to enforce abstinence, as still practiced under medical or law enforcement responsibility in a number of countries, for an estimated 300,000 people, gravely disregards ethical principles and fails to reach desired outcomes (UN 2012). In many other countries, harm reduction measures and addiction treatments (detoxification, therapeutic communities, substitution therapy) are available for convicted addicts. Such interventions must be optional as an alternative to a regular prison regime, in the prison milieu or on court order outside of prison in a community-based service. In-prison services must follow the same rules as community-based services and can be equally effective.

Milder forms of coercion (threats of losing a job, a financial support, the spouse) happen in situations where other measures fail and are typical examples of ethical conflict between interests of patient and others. Acceptability depends on failed attempts to find alternatives or on an agreement with the addicted person. The latter is the basis of a therapeutic intervention called contingency management (the patient agrees on defined consequences, e.g., losing driver license, notification of employer if breaking the therapeutic contract). As a rule, positive consequences of reaching a defined goal are more effective than negative consequences of missing a goal.

Requirements At The System/Network Level

Coverage of treatment needs is one of the priorities in a public health perspective, to offer treatment to all persons in need of treatment. Individual care may be optimized by high-quality treatment, but public health cannot accept high-quality standards for a few as long as the many are not reached adequately. Good access to treatment asks for a range of qualified services of different types, easily reached by public transport, open for all in need without discrimination. The range of services must include detoxification, long-term drug-free treatment, opioid substitution treatment, rehabilitation programs, and harm reduction approaches; it also must offer early brief interventions in general medical and social services. Psychosocial assistance, psychopharmacology, and behavioral psychotherapy are also essential elements.

The care system must be an integrated system that enables therapeutic and harm reduction services to work together, in order to provide a continuum of care, including:

– Easily accessible low threshold services that meet the immediate needs of active drug users

– Clear processes for motivating users to move away from drug dependent lifestyles

– Clear processes for referring users into structured treatment programs that promote stabilization or abstinence

This principle includes a monitoring of the treatment needs in a given population and, accordingly, a careful planning of the treatment system as a whole, in response to the identified needs. Ethical and professional responsibilities are identified at multiple levels: medical practitioners are responsible for good individual care, service directors are responsible for good practice and continued education in their services, and health authorities are responsible for good and cost-effective coverage of treatment, for appropriate regulations and resources.

Research

The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 (repeatedly amended) formulates ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. The principles fully apply in research on substance abusers and substance dependent persons. Special attention is due to the vulnerability of this target group for stigmatization and for legal prosecution when illegal substances are involved. In the interest of good coverage and best use of available resources, the clinically preferred randomized controlled trials on the short-term efficacy of specific methods must be complemented by prospective observational studies, providing evidence on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness (including acceptability, retention, and midto long-term outcomes).

Conclusion

The risks for developing substance dependence and other forms of abuse are increasingly well researched. Promising interventions are available, at the individual and at the population level. Ethical rules, typical conflicts, and ways how to deal with those exist in some detail. However, there is much need for a better implementation, in the education of concerned professionals, in health policy, and in service provision. One of the main barriers is the stigmatization of abusers and of those who care for them.

Bibliography :

- (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-5. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Council of Europe. (1950). European convention on human rights. Amended 2010. https://ec.europa.eu/ digital-agenda/sites/digital-agenda/files/Convention_ENG. pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015.

- Gowing, L., Ali, R. L., Allsop, S., Marsden, J., Turff, E. E., West, R., & Witton, N. (2015).

- Global statistics on addictive behaviors: 2014 status report. Addiction, 110, 904–919.

- Murray, C. J. L., & Lopez, A. D. (1997). Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet, 349, 1436–1442.

- (2008). Principles of addiction treatment. A research-based guide (3rd ed.). Rockville: National Institute of Drug Abuse. revised 2012.

- Rhodes, T., & Hedrich, D. (Eds.). (2010). Harm reduction: Evidence, impacts and challenges. Lisbon: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.

- (1948). The universal declaration of human rights. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/. Accessed 19 May 2015.

- (2012). Compulsory drug detention and rehabilitation centers. A joint statement of 12 UN agencies.

- (2015). World Drug Report 2014. http://www. unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/WDR2014/WorldDrug_Report_2014_web.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015.

- Van Amsterdam, J., Nutt, D., Phillips, L., van den Brink, W. (2015). European rating of drug harms. Journal of Psychopharmacology 1–6. doi:10.1177/0269881115581980.

- Volkow, N. D., Fowler, J. S., & Wang, G. J. (2003). The addicted human brain: insights from imaging studies. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 111, 1444–1451.

- West, R. (2006). Theory of addiction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- West, R.(2002). World health report. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- West, R. (2009). Guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO ICD-10. (1990). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Version 2015. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Helmchen, H., & Sartorius, N. (Eds.). (2010). Ethics in psychiatry. Dordrecht: Springer Publishers.

- UNODC/WHO. (2008). Principles of drug dependence treatment. Discussion paper. http://www.unodc.org/documents/drug-treatment/UNODC-WHO-Principles-of-Drug-Dependence-Treatment-March08.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015.

- (2010). ATLAS on substance use – Resources for the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization.

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.