This sample Behavioral Management In Probation Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Overview

Behavioral management is the newest framework for community supervision; it is a hybrid combining the traditional theoretical approaches of law enforcement (monitoring and compliance) and social work (resource broker and/or counseling). The social work perspective was more commonplace in the USA until the 1970s and is currently slowly eroding in other countries over the last several decades. The erosion is part of the diminishing support for rehabilitation-type programming for offenders as well as the increased concerns about offender accountability and public safety. Enforcement and compliance management are now the more predominant framework in the USA with other countries emulating this style of supervision given the emphasis on offender accountability. As a hybrid approach, behavioral management arms the probation officer with a new toolkit that recognizes the balance between offender change and accountability, and it offers new strategies for managing the offender in the community that incorporates evidence-based practices and treatments (“what works”). The behavioral management supervision model is based on a theoretical framework that offender change is due to a trusting, caring relationship between the offender and the officer where the emphasis is on structure and accountability. The officer facilitates offender change through therapeutic techniques of individualized case plans, cognitive restructuring, and graduated responses to positive and negative behaviors.

This research paper reviews the literature on the effectiveness of community supervision and then explores the concepts of behavioral management with examples from existing efforts across the globe. Next this research paper discusses the policies, programming, and developmental issues that affect the likelihood of behavioral management becoming predominant in supervision settings. This is critically important since a behavioral management framework requires organizational strategies to emphasize an altered mission and goal for the supervision organizations to encompass structure along with programs and services to alter offender outcomes.

Evolving Nature Of Community Supervision Models

Community supervision is the broad category that refers to any correctional control in a community setting. This generally covers pretrial (preadjudication), probation (sentence that involves community control), and parole (post-incarceration) as well as case management of offenders in the community. Probation had its early roots as a humane method of dealing with alcoholics. John Augustus, the grandfather of contemporary probation in the USA, realized that alcohol abuse contributed to workers being unreliable. Probation was conceived as a court service designed to reduce the use of jail sentences for first-time offenders. The early era of probation was focused on alternatives to incarceration and assisting those with needs (mostly alcohol abuse). In the 1970s, more emphasis was placed on oversight (law enforcement) and enforcement of conditions in the USA as support for rehabilitation dwindled (Garland 2001). The current emphasis on enforcement of the conditions of release (i.e., generally reporting, informing the officer of their whereabouts, and other emphasis on controls) dominates probation services.

Probation supervision is built on suppressing criminal behavior through a contact approach. Contacts, or face-to-face meetings between offenders and community supervision officers, are the main tool of overseeing offender behavior. While on probation, the offender has a series of liberty restrictions that define the requirements of supervision. Some of these restrictions are imposed by the court (for probation or pretrial supervision) or the parole board (for parole). Others are part of standard supervision conditions such as limiting activities and curfews, requirements to report to the supervision officer, no possession of guns, and so on. That is, the offenders have a set of rules to guide their behavior. The purpose of supervision monitoring is to improve compliance with these conditions. The notion is that offenders will be deterred from further criminal behavior with the threat of incarceration (due to failure to comply with the conditions of release). The core component of supervision – contacts – has been empirically tested in a limited fashion, primarily with studies of intensive supervision (more contacts), where frequency of supervision has not resulted in improved results (MacKenzie 2006; Petersilia and Turner 1993; Taxman 2002). A recent study of low-risk offenders (i.e., offenders that have a low probability of further criminal justice involvement) found that increasing the number of contacts with supervision officers did not result in reductions in recidivism (Barnes et al. 2012). There have been no experiments or studies on whether being on probation (i.e., having required contacts between the probation officer and offender) or having no oversight has any impact on future offending behavior. This limits the ability to understand whether supervision suppresses offending behavior or how supervision leads to more desirable impacts on offender behavior. The question of what type of supervision is most effective has largely been unanswered except for a recent systematic review that favored the risk-need-responsivity (RNR) (behavioral management) model of supervision (Drake 2011).

A small body of literature has examined the impact of probation on per-person offending rates. MacKenzie and Li (2002) examined the rate of offending of probationers and found that during the period of supervision, their self-reported offending rates decreased slightly. They found that having more conditions of supervision or requirements did not impact offending rates or offending behavior. But there is caution that needs to be acknowledged given that this was a quasi-experimental design with no control group (no one was assigned to not being supervised by an authority of the state) or comparison group; instead the study examined pre-post self-reported behaviors of offending. MacKenzie and Li (2002) also raise questions about whether added supervision conditions are useful given that the additional conditions do not appear to have a deterrent effect.

Supervision studies have primarily focused on contact levels and caseload size. The premise is that the caseload size is used as a proxy for the amount of time that the officer can devote to each offender. Two outstanding questions are: (1) what is the optimal size of the caseload a probation officer can manage to increase the success on probation? and (2) what impact does increasing the contact between the probation officer and the probationer have on contacts? The question about caseload size was addressed in several randomized trials to assess whether a caseload of 25–40 (depending on the study) had any impact on offending behavior. The theory was that having too many probationers to supervise would reduce the effectiveness of supervision by reducing the time that the offender can spend with the officer (Taxman 2002; MacKenzie 2006). Of course, these studies did not consider the difference when caseloads were 100 or more as compared to prior studies when caseloads were under 40 offenders per officer. Most of the caseload size findings from these studies (examining smaller caseloads under 40 offenders) were null, meaning that the caseload size did not affect offender outcomes. Since the concept of size of caseload was not associated with a particular theory of supervision, the studies did not contribute to a better understanding of what the probation officer should do as part of supervision.

Dosage studies (i.e., “frequency of contact”) were the next series of studies conducted to detect how much contact is needed to improve offender outcomes. This set of studies was built on similar theoretical deficits in that the studies did not examine different styles of supervision but instead examined how more contact between the officer and offender/probationer affected outcomes. Petersilia and Turner (1993), in the largest multisite randomized trial (13 sites for probation supervision and 2 for parole) in probation supervision, found that intensive supervision services (the amount of required contacts varied by site) served to increase technical violations (i.e., allowed officers to be aware of compliance issues) but had no impact on rearrests. Intensive supervision heightened the number of contacts between the officer and probationer, increased the use of drug testing to detect drug use, and increased conditions of release. Yet, it had no notable impact on offending behaviors of offenders. The increased contact model has been found to be ineffective in reducing criminal behavior, although it is acknowledged that the law enforcement component has the potential to actually increase technical violations (Aos et al. 2006; MacKenzie 2006; Taxman 2002).

The caseload size and dosage studies on supervision have not found any impact on these factors on improvements in supervision outcomes. That is, the law enforcement and monitoring approach does not appear to improve outcomes, but this can only be stated with qualifications given that insufficient studies have examined or compared different types of supervision strategies. A recent systematic review by Drake (2011) found that the RNR model of supervision has the greatest impact on offending, followed by supervision with treatment conditions. Other forms of supervision such as contact only or contacts and drug testing (controls) had no impact on outcomes. The RNR model of supervision allows supervision to be more “client centered,” where the goal is to tailor probation conditions and style of supervision to the individual. This draws from the “what works” (evidence-based practices) literature, focusing on reducing the risk of the individual offending by attending to dynamic criminogenic needs through specific case plans and responsive treatment programs. A major component of the model – besides the hard technology of using standardized tools for screening, assessment, and placement in appropriate programming – is the emphasis on the “soft” technology of deportment or the relationship between officer and offender (Taxman 2002, 2008a; Taxman et al. 2004). The RNR model of supervision addresses the tension between enforcement and social work models of supervision by realigning the goals of supervision officers to be behavioral managers. The theoretical framework is that offender change is a function of attention to target, proximal behaviors that are crime reducing, and a trusting relationship between the offender and officer.

The RNR model draws upon the importance of probationers and officers having a working relationship to address the general factors that affect involvement in criminal conduct. Recent studies illustrate how improved working relationships (e.g., empathy, trust, care, voice) have a positive relationship with offender outcomes (Taxman and Ainsworth 2009). Probationers (with mental health conditions) who perceived their officer to be tough had more failures and higher numbers of violations than those that did not (Skeem et al. 2007). Thanner and Taxman (2003, 2004) found that when offenders reported that they had a “voice” (i.e., the probation officer allowed the offender to participate in deciding the type of sanctions for failure to comply with requirements), reductions occurred in arrests and positive drug tests. While recognizing the importance of the person-centered model in supervision, James Bonta and colleagues in Canada studied whether probation officers have the appropriate interpersonal skills, role modeling, and communication skills to work effectively with offenders in an evidence-based practices model of risk, needs, and responsivity. The general findings from their studies are that probation officers do not have these skills and, even if the officers have the skills, they do not use them in supervision of offenders (Bonta et al. 2011).

Within the field, the following principles are considered important to an evidence-based supervision system (Taxman 2008b; Taxman et al. 2004; NIC 2004):

1. Manage risk levels. Providing higher-risk offenders with more structured control and treatment services, it is possible to reduce recidivism. Using risk level to articulate a supervision policy based on providing more intensive services by risk level serves to use probation resources wisely and use treatment services in a fashion that generates the best results. A related finding is that low-risk offenders could be supervised with fewer resources, and by providing low-risk offenders with minimal services, one can obtain relatively positive findings. In a recent experiment with low-risk offenders, Barnes and colleagues (2010) found that minimal supervision (average of 2.5 contacts per year) had similar recidivism results as offenders supervised on a more traditional schedule (average 4.5 contacts per year).

2. Treat dynamic criminogenic needs (i.e., substance abuse, impulsive behavior, criminal peers, and criminal thinking). Offenders vary considerably in the factors that affect their criminal behavior. While risk level indicates the likelihood of further involvement with the justice system, criminogenic needs identify the dynamic factors that affect involvement with criminal behavior. These dynamic factors can be altered with the use of proper treatment programming and correctional controls. The criminogenic needs should be targeted to improve outcomes.

3. Manage compliance. The most difficult part of any behavior change is sustaining the effect. Probation agencies can assist with compliance with judicial or parole board mandates. Compliance is similar to monitoring offenders, but the key is to use short-term goals to allow offenders to achieve positive outcomes; shortterm goals are stacked towards longer-term outcomes of reduced drug use and alcohol abuse and continued involvement with the justice system. Retention strategies are important to achieve longer-term impacts. The use of administrative sanctions (matrix of responses to different types of behavior such as drug use, failure to pay fees, etc.) is recommended to provide graduated, structured responses.

4. Create an environment for offender change. An important part of the EBP model is the creation of an environment to support offender change. A focus only on revocations is counter to the emphasis on behavioral change, which is long and difficult. More attention is needed to creating an organizational culture that supports trusting relationship on supervision. The working relationship between the offender and the probation officer is an important component of the change process in that it builds support for change (Taxman and Ainsworth 2009).

This constitutes the behavioral management model of supervision where therapeutic strategies are used to facilitate offender change. The toolkit for supervision officers includes motivational enhancements, cognitive restructuring for meeting criminogenic needs and compliance management, and targeted responses to behaviors; all of this must occur in an environment where behavioral change is expected to be slow and steady with some relapses. In fact, relapses are expected to be commonplace and provide the tools to build resiliency to further change.

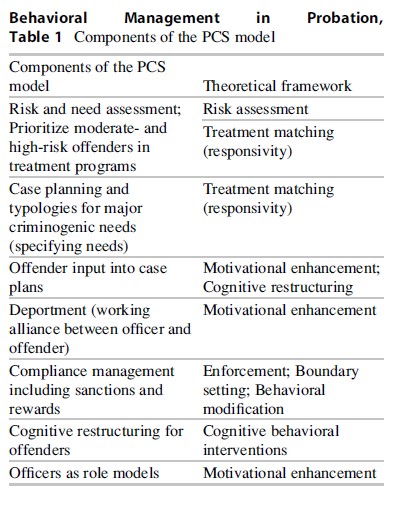

Maryland Proactive Community Supervision Study

A recent systematic review found that the evidence-based practices model that emphasizes behavioral management reduces recidivism by 16 %, in contrast to enforcement supervision (no impact) and supervision with treatment (10 % effect) (Drake 2011). The question is whether an evidence-based supervision model can be implemented and can deliver the same expected results of reduced recidivism as the “what works.” The Maryland Proactive Community Supervision (PCS) experiment was a test of this model (see Taxman 2008a). Taxman and colleagues (2004) translated the risk-needresponsivity (RNR) model into a model for probation supervision given that the original model of “what works” principles was primarily geared towards treatment-related programming. The core components of the probation supervision model were based on the following theoretical approaches that blend accountability with therapeutic interventions, as shown in Table 1. One key component is the role of the supervision officer in helping the offender facilitate behavioral change by using cognitive restructuring strategies into routine practices of risk and need assessment, case planning, and compliance monitoring. That is, officers were trained in using cognitive restructuring and motivational interviewing as part of how they address traditional offender processing procedures (e.g., assessment, case planning, treatment and control monitoring, and determination of progress). The PCS model was designed to address the tension between the law enforcement and social work frameworks, with the emphasis on using quality contacts as a conduit for offender change. The behavioral management components were designed to integrate cognitive restructuring and behavioral modification frameworks within supervision settings by having the officer use these techniques with offenders.

Behavioral Management in Probation, Table 1 Components of the PCS mode l

The PCS offender supervision process model consists of five major components (see Taxman et al. 2004 for more details). A five-item risk screener was used to determine initial assignment. Offenders scoring moderate to high risk are then involved in a lengthier assessment process involving the Level of Service Inventory– Revised, a third-generation risk assessment tool (Andrews et al. 2006). Officers also conduct a thorough review of the person’s place of residence and social networks. As part of the process, the offender is asked about their desired goals during supervision. All of this information is used to assess the factors that affect criminal behavior, with attention to the specific typology of criminogenic behavior. The six typologies (and related goals) are disassociated (develop prosocial network), drug addiction (achieve abstinence and recovery), drug-involved entrepreneur (obtain prosocial employment), violent offender (address power and control issues), domestic violence (address relationship and control issues), mental health (continue treatment and address support network), and sexual deviance (achieve control over urges and manage behavior). The typology helps define the components of the case plan, including the appropriate type of treatment programming and controls applied, such as drug testing, curfews, house arrest, or other types of mechanisms to limit liberties. On a monthly basis, the offender and the supervision officer review progress on the case plan (see Taxman 2008a). The case plan is revised monthly based on the offender’s progress in meeting goals and the offender’s attitude. Offenders are given no more than three goals a month, with participation in treatment services prioritized as one of the key goals.

The process hinges on the offender’s engagement to achieve ownership of the case plan through a positive working relationship with the supervising officer. The agency achieves the emphasis on engagement through a series of skill development sessions that emphasize (1) learning to use motivational interviewing strategies, (2) using cognitive restructuring strategies to assist offenders in problem solving to address their criminogenic needs, and (3) using performance measurements (e.g., drug tests, attendance) to assess offenders’ progress. The skill development efforts provide officers with the ability to adapt and translate motivational interviewing, behavioral modification, and cognitive restructuring in a community supervision environment (see Taxman et al. 2004) into traditional functions of assessment, case planning, monitoring, and compliance assessments. These skill-building components provide the officers with new behavioral strategies to work with offenders.

The PCS model of skill development and refocus of supervision could not be accomplished without changes in the culture of the probation officer. The agency created a social learning environment (for staff and probationers) with an emphasis on building a probation culture that supported officers’ use of the behavioral management strategies instead of traditional law enforcement techniques. The agency adapted core tenets of a social learning environment: greet offenders with proper salutations, shake hands with the offender upon entrance and exit, and maintain eye contact with the offender during all personal conversations.

Additionally, the face-to-face contact of supervision is realigned. The traditional face-to-face contacts are altered to bilateral information exchange sessions where the goals of supervision could be assessed, refined, and restated. Assessment and other data collection exercises are shared with offenders to allow them to learn about their own behavior. Finally, performance measures for offenders, supervision staff, and PCS offices are used to reinforce the emphasis on behavioral management strategies such as number of offenders employed, number of goals achieved, and then attention to the accomplishments per typology. Officers and probationers reviewed the target goals in each section as part of the behavioral contract and these accomplishments are used to build future target goals. The emphasis on target goals is to gradually improve the probationers’ success on probation. This is the process that defines the behavioral management framework used in a responsive face-to-face contact system.

In a place-based experimental design where four probation/parole offices in Maryland implemented the behavioral management supervision model (PCS) and four similar offices used the traditional law enforcement supervision style, logistic regression results found that, controlling for length of time on supervision and prior criminal history, offenders that were supervised in the behavioral management style were less likely to be rearrested (30 % for the PCS and 42 % of the non-PCS sample; p < 0.01) and less likely to have a warrant issued for technical violations (34.7 % of the PCS group and 40 % for the non PCS group; p < 0.10). The study also included a process evaluation to assess the degree to which the key components of the model were implemented. The assessment inventory (LSI-R) was implemented in 70 % of the cases and the typologies were used in 56 % of the cases. The typologies were used as a vehicle to identify short-term goals to improve outcomes, and for those that were assigned typologies, a greater percentage were placed into appropriate programming and controls than in the control group. Some officers did not implement the model as planned which resulted in some cases with no typology assignment. In these cases, fewer services were obtained for the probationer. Several replications of the application of the riskneed-responsivity model of supervision have confirmed reductions in recidivism (Drake 2011).

Further Work On Behavioral Management (RNR) Supervision Models

Trying to disentangle the effective mechanisms of supervision is the subject of a growing body of research. The focus of attention has been on (1) specialized caseloads, (2) different collaboration between probation agencies and treatment providers, (3) the use of graduated sanctions to manage offender behavior, (4) “light” supervision for low-risk cases, and (5) improving the problem-solving skills of officers.

Specialized Caseloads. Very little research has been conducted on the impact of specialized caseloads, or the concentration of offenders with like criminogenic needs with one officer. The available research has been on offenders with mental health disorders or domestic violence. In a national survey of specialized caseloads, special mental health units were distinguished by (1) caseloads consisting of clients with mental disorders, (2) reduced caseload sizes, (3) trained officers in mental health issues and behavioral management problems, (4) integration of probation and community mental health resources, and (5) use of problem-solving strategies to address treatment noncompliance. Three separate evaluations of specialized caseloads for probationers with mental illness have found a tendency towards positive outcomes of reduced technical violations or rearrests, although these studies are not conclusive given their weak research designs and measures (Epperson 2009). Specialized units for domestic violence caseload have shown similar results to intensive supervision programs with increased contacts that have lead to increased violations. The emphasis of most domestic violence research focused on enforcement and control of offenders, which has the same outcomes of other intensive supervision studies – that is, the specialized caseloads led to greater probation violations.

Collaboration Models Between Probation and Treatment Providers. Most community correctional agencies in the USA do not provide treatment services directly by the probation agency. Instead, the offender is referred to treatment programs provided by publically funded treatment programs or the probation agency contracts for services in the community. Increasing the access to treatment services has been a long-standing challenge for probation and community corrections agencies in that the services are seldom designed specifically for an offender population. The specialized case management services, commonly referred to as Treatment Accountability for Safer Communities (TASC), are designed to provide a bridge between justice and treatment agencies. The five-site evaluation of the TASC case management model found that case management did not result in reduced recidivism or technical violations and did not improve access to treatment services. In the sites where positive findings occurred, the service agency also provided treatment services and therefore directly improved access to treatment (Anglin et al. 1999). This is a common theme regarding case management; agencies that provide both case management and treatment are more likely to improve outcomes.

In contrast to a brokerage model of service linkage, Taxman (1998) developed the concept of a policy-driven seamless system of care. The concept was built upon information sharing across the spectrum of service delivery: assessment, drug testing, treatment access and participation, supervision requirements, and outcomes. The goal was to have probation officers and treatment providers jointly share information that would be useful in their efforts to assist offenders. The study results vary considerably, mainly based on the features of the seamless system that are present. For pretrial supervision focusing on testing, treatment, and sanctions, a randomized trial found reductions in rearrest rates for higher-risk offenders (Harrell et al. 1998). In another study of probation that used a person-centered model of probation supervision, the findings are also mixed. An assessor in the probation office would screen for substance abuse disorders and then target offenders to appropriate treatment. Treatment should be 9 months in duration with two levels of care (generally a step down to outpatient but it could be from in-jail treatment to outpatient care, drug testing, and sanctions). The probation/parole officer’s role was as a resource broker, working with the treatment counselor on treatment access, monitoring compliance with drug treatment requirements, and responding to positive drug test results. The study resulted in increased access to treatment services and increased days in treatment, but the seamless intervention was more costly to deliver and did not result in reduced recidivism for some higher-risk offenders (Alemi et al. 2006; Taxman and Thanner 2006). For higher-risk offenders, there was a reduction in arrests and opiate drug use (Thanner and Taxman 2003; Taxman and Thanner 2006). A more recent study used a slightly different seamless framework but added a manualized cognitive behavioral therapy treatment sessions offered in the probation office. Again, there were increases in treatment access, and the study found improvements in outcomes for moderate-risk offenders, but not for high-risk offenders (Taxman and Belenko, 2011). The provision of treatment in the probation office did not universally improve outcomes for offenders, but the study found that certain treatments are more effective for some offenders. Overall, the study found that offenders with drug dependence disorders tended to have less positive outcomes than those with abuse disorders. It appears that the outpatient treatment is not as effective for those with dependence disorders.

Another study focused on probation/parole officer and treatment provider working together in a collaborative model of care. The Step ‘n Out study, conducted in six sites, required the officer and treatment provider to work together on a collaborative behavioral management (CBM) process of accessing treatment needs, reviewing treatment progress, and using a structured reward schedule to incentivize offenders for positive behavior (Friedmann et al. 2008). CBM is modeled after contingency management, which focuses on providing rewards for positive behaviors (see Stitzer et al. 2011). The study found a treatment effect for offenders with substance use disorders, particularly those that did not use hard-core drugs (e.g., opiates, cocaine, methamphetamine) (Friedmann et al. 2012). In this model, the probation officer and treatment provider have frequent meetings to review the progress of offenders.

Use of Graduated Responses. Supervision officers have tremendous discretion regarding the handling (and managing) of offender out-comes. As drug treatment courts and the seamless system evolved, the emphasis was on using gradual responses to offender noncompliance, commonly referred to as graduated sanctions. The notion is that sanctions need to be swift, certain, and severe (increasing in intensity based on the number and type of violation behavior). Sanctions can be delivered by probation or parole officers, or they can be delivered by judicial or parole board authorities. The former is referred to as administrative sanctions and the latter as sanctions. Swiftness means that the sanction occurs in a period of time close to the noncompliant event. Certainty means that the sanction is delivered as it was indicated. Severity refers to the type of response and whether it involves liberty restrictions such as incarceration. Paternoster (1987), in a study of perceptional deterrence, found that swiftness and certainty are more likely to influence offending behavior. While there has been general support for probation and parole officers using administrative sanctions (a set regulatory procedure) or a matrix of noncompliant behavior and type of responses, there are relatively few empirical studies of the degree to which administrative sanctions reduce offending behaviors. In a non-experimental study examining the use of graduated sanctions on parolees during the first year after release from prison, researchers found that graduated sanctions could alter the offending behaviors of offenders. The use of graduated sanctions in a manner that features swift, certain, and severe can enhance the suppression effect of parole on criminal behavior. Steiner et al. (2012) did not examine the use of any specific sanction schedule and used the sanction mechanism as a proximity for severity of response (i.e., supervising officer gives a privilege restriction, parole board or a hearing officer, placement in a halfway house, and formal revocation hearing where it was possible the offender may have been returned to prison). They found that sanctions were effective regardless of offender risk level, but younger offenders did not respond as well to sanctions.

Another graduated response is the use of rewards. Following the model of contingency management in the substance abuse treatment literature, rewards are to be delivered swiftly, certainly, and severely (progressively increasing in value). Rewards tested in drug treatment programs demonstrate that offenders respond well, with rewards impacting drug use and treatment retention. Marlowe and colleagues (2009) found that rewards were very successful for young offenders in a drug court setting in terms of reducing offending behavior. Rudes and colleagues (2011) outlined how rewards could be adapted in justice-type settings and used as part of a progressive behavioral management scheme. Rewards create an environment for probation that is consistent with the efforts to facilitate offender change. That is, recognizing that offenders respond to acknowledgment about positive steps during probation facilitates positive outcomes.

Low-Risk Offenders. The risk-needresponsivity model focuses attention on moderate-to high-risk offenders. The triage model indicates that low-risk offenders should not have the same oversight or monitoring as other offenders, presuming that their criminogenic needs are minimal (similar to their low criminal justice risk status). This principle is based on the lower recidivism rates of low-risk offenders. Barnes and colleagues (2012) conducted an experiment where low-risk offenders were supervised on administrative caseloads (caseloads averaging 400 offenders per officer with requirements of two in-person contacts and two phone contacts a year) or traditional supervision (monthly in-person contacts). The study found that offenders assigned to traditional supervision are more likely to abscond from probation (partially a function of the traditional supervision defining absconding as missing for 2 months of contacts, whereas the experimental group had to not have contact in 3 months). There were no statistically significant differences in the rearrest rates or drug test positive rates. In examining the comparative effectiveness of the two models for supervising low-risk offenders, the experiment confirms that there is a slight advantage in reducing contact levels in that there are fewer absconders. Similar to intensive supervision, which finds that increased attention is likely to denote more compliance-related issues, this study found that low-risk offenders can be managed with less supervision. These findings are important for policy considerations in that risk level is an important consideration for managing offenders in the community.

Skill building of Officers. The behavioral management approach to supervision has yielded attention to an important part of the equation to achieve more positive offender outcomes: the skills of the officers supervising offenders. Officer skills are important because the model, as described above, relies upon officers to create an environment where change can occur, to engage offenders in the change processes, to use cognitive restructuring techniques in working with offenders, and to use problem solving and other strategies to address compliance-related issues. The notion that officers need to be trained on the basic premises of the behavioral management principles (including RNR) was evident in the MD PCS study (cited above), which recognized that preservice training and ongoing in-service training did not include the basic principles of managing risks and attending to criminogenic needs. The MD PCS project designed and built three training programs: Officer Engagement skills (based on principles of motivational enhancement and interviewing), “Sizing Up” (based on applying the risk and need assessment tools), and in-office refresher training (see Taxman et al. 2004). More recent attention has been given to enhancing the training of officers through similar curriculums that focus on structuring sessions, relationship-building skills, behavioral techniques, cognitive techniques, and effective correctional skills (Bonta et al. 2011; Robinson et al. 2011). The premise is that in order for officers to use the RNR principles, their work flow needs to be adapted to the principles of their work environment, including attention to intake and assessment, monitoring compliance, monitoring treatment compliance, and reinforcing cognitive restructuring.

Without training in applying the RNR principles, it is unlikely that officers will discuss procriminal attitudes or cognitions with offenders and even more unlikely to use cognitive intervention techniques with their clients. Bourgon et al. (2011) found that the Canadian STICS training, which included review tapes, improved officers’ discussion about procriminal attitudes and results in increased utilization of cognitive techniques (namely, helping the offender to examine their own behavior and outline options). In a cox regression model, the authors also found that the use of cognitive techniques reduced offending rates. Bonta and colleagues (2011) had similar findings when most probation officer-offender contacts focused on probation conditions and noncriminogenic factors (e.g., work, sports). The increased training improved the focus on procriminal attitudes among the experimental group with more attention to attitudes and employment and educational issues. Offenders supervised by officers using the skills were also significantly less likely to reoffend.

Conclusion

The behavioral management model of supervision is currently being implemented in the USA as well as other countries. The recent systematic review confirmed that the RNR supervision model had better outcomes than other supervision approaches (Drake 2011). However, probation officers are not aware of how the risk-need-responsivity (RNR) principles apply to supervision, and therefore, the successful implementation of this model will depend on the technology transfer strategies that are used. The “what works” model (RNR) has primarily been targeted to treatment programs, but as learned in the MD PCS demonstration, it is possible for supervision officers to use the RNR principles. The challenge is to adapt RNR to align with supervision. RNR relies upon principles of behavioral management in terms of recognizing that there are boundaries that need to be in place (enforcement) but also that therapeutic techniques of individualized care, cognitive restructuring, and graduated response are useful to achieve improvements in supervision outcomes. The advent of various training protocols (i.e., STICS in Canada, STARRS in federal probation, EPICS in other supervision models) illustrates the complexity of the transfer process and the need to import RNR principles into supervision practices.

The proliferation of these curricula illustrates that there is a need to improve the skill sets of officers to use the RNR principles, especially given that few officers are trained in social work or counseling skills. This becomes the challenge to implementation in that supervision staff need to develop new skills to work with offenders in a different manner.

The other challenge is the development of policies to support the use of behavioral management strategies. An important part of the model is to use the risk level to allocate resource levels so that moderate and high-risk offenders receive ongoing (and more intensive) care than low-risk offenders. While this is an intuitive policy, it is actually more challenging to implement since officers tend to find lower-risk offenders easier to supervise (e.g., they tend to be less resistant). But other policies that are important to put in place have to do with collaborations with treatment providers and using graduated responses. The collaboration with treatment providers is an important policy issue. The working relationship between supervision and treatment agencies should be defined at the office level to ensure that treatment providers use evidence-based treatments and that information is shared between the two disciplines. The creation of policy-level agreements will avoid probation officers having different agreements with treatment providers and having different expectations from the treatment providers. The use of graduated responses – both negative and positive – is another policy issue in that the agency needs to determine what can be used as reinforcers both in terms of liberty restrictions (sanctions) and liberty enhancers (rewards).

This discussion of behavioral management supervision has not included another dimension that is being integrated into the workspace of supervision: temporally and spatially based supervision. The increasing awareness that some offenders are concentrated in certain neighborhoods has spurred an interest in community-based probation models that focus on ameliorating the risks of the individual and the place. These models are based on the premise that concentration of offenders into typically resource-deprived communities only serves to undermine supervision; the demands of the community override the requirements of supervision. Byrne (2009) also points out that targeting supervision at high-risk times – generally referring to the early part of the supervision period or the first 90 days – is a sound strategy for reducing recidivism. During this early period, offenders are more likely to fail (MacKenzie and Li 2002; MacKenzie and Brame 2001), and officers have an opportunity to set expectations about the behavior of offenders under supervision. The early period of supervision is when offenders are going to test the conditions of release. Little research has been conducted on different methods for improving compliance during this early period of supervision, but it is an important factor.

Behavioral management offers a solution to the age-old debate about supervision being enforcement vs. social work. Since the behavioral management (RNR) model incorporates a balance between compliance-focused supervision and working on offender change issues, it offers a model of supervision that fulfills the multiple goals of sentencing. Moreover, behavioral management helps assist officers in learning strategies to facilitate offender change. The test over time will be whether behavioral management supervision can be successfully implemented and what the scaled-up version will have an impact on offenders’ outcomes.

Bibliography:

- Alemi F, Taxman FS, Baghi H, Vang J, Thanner M, Doyon V (2006) Costs and benefits of combining probation and substance abuse treatment. J Ment Health Policy Econ 9(2):57–70

- Andrews DA, Bonta J, Wormith JS (2006) The recent past and near future of risk and/or need assessment. Crime Delinq 52(1):7–27

- Anglin MD, Longshore D, Turner S (1999) Treatment alternatives to street crime. Crim Justice Behav 26(2):168–195

- Aos S, Miller M, Drake E (2006) Evidence-based public policy options to reduce future prison construction, criminal justice costs, and crime rates(. Washington State Institute for Public Policy, Olympia, p 44, No. 06-10-1201

- Barnes GC, Ahlman L, Gill C, Sherman LW, Kurtz E, Malvestuto R (2010) Low-intensity community supervision for low-risk offenders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Exp Criminol 6(2):159–189

- Barnes GC, Hyatt JM, Ahlman LC, Kent TL (2012) The effects of low-intensity supervision for lower risk probationers: updated results from a randomized controlled trial. J Crime Justice 35:200–220

- Bonta J, Bourgon G, Rugge T, Scott T-L, Yessine AK, Gutierrez L, Li J (2011) An experimental demonstration of training probation officers in evidence-based community supervision. Crim Justice Behav 38(11):1127–1148

- Bourgon G, Gutierrez L, Ashton J (2011) The evolution of community supervision practice: the transformation from case manager to change agent. Irish Probat J 8:28–48

- Byrne J (2009) Maximum impact: targeting supervision on higher-risk people, places and times. Public Safety Performance Project. The PEW Center on the States

- Drake EK (2011) “What works” in community supervision: interim report. Washington State Institute for Public Policy, Olympia, Document No. 11-12-1201

- Epperson MW (2009) Criminal justice involvement and sexual HIV risk among drug-involved men and their primary female sexual partners: individual and couplelevel effects (Dissertation). Columbia University

- Friedmann PD, Katz EC, Rhodes AG, Taxman FS, O’Connell DJ, Frisman LK et al (2008) Collaborative behavioral management for drug-involved parolees: rationale and design of the Step’n Out study. J Offender Rehab 47(3):290–318

- Friedmann PD, Green TC, Taxman FS, Harrington M, Rhodes AG, Katz E et al (2012) Collaborative behavioral management among parolees: drug use, crime & re-arrest in the Step’n Out randomized trial. Addiction 107:1099–1108. PMCID: PMC3321077

- Garland D (2001) The culture of control: crime and social order in contemporary society. Oxford University Press Ill: University of Chicago Press

- Harrell A, Cavanagh S, Roman J (1998) Findings from the evaluation of the DC superior court drug intervention program. The Urban Institute, Washington, DC

- MacKenzie DL (2006) What works in corrections: reducing the criminal activities of offenders and delinquents. Cambridge University Press, New York: Oxford University Press

- Mackenzie DL, Brame R (2001) Community supervision, prosocial activities, and recidivism. Justice Q 18(2): 429–448

- MacKenzie DL, Li SD (2002) The impact of formal and informal social controls on the criminal activities of probationers. J Res Crime Delinq 39(3):243

- Marlowe DB, Festinger DS, Arabia PL, Dugosh KL, Benasutti KM, Croft JR (2009) Adaptive interventions may optimize outcomes in drug courts: a pilot study. Curr Psychiatry Rep 11(5):370–376. doi:10.1007/ s11920-009-0056-3

- Paternoster R (1987) The deterrent effect of the perceived certainty and severity of punishment: a review of the evidence and issues. Justice Q 4(2):173

- Petersilia J, Turner S (1993) Intensive probation and parole. Crime Justice 17:281–335

- Robinson CR, VanBenschoten S, Alexander M, Lowenkamp CT (2011) Random (almost) study of Staff Training Aimed at Reducing Re-Arrest (STARR): reducing recidivism through intentional design. Fed Probat 75(2):57–63

- Rudes, Danielle S, Faye S. Taxman, Shannon Portillo, Amy Murphy, Anne Rhodes, Maxine Stitzer, Peter Luongo, & Peter Friedmann. 2011. “Adding Positive Reinforcements in a Criminal Justice Setting: Acceptability and Feasibility.” The Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 42(3): 260-270.

- Skeem JL, Louden JE, Polaschek D, Camp J (2007) Assessing relationship quality in mandated community treatment: blending care with control. Psychol Assess 19(4):397–410. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.19.4.397

- Steiner B, Makarios MD, Travis LF, Meade B (2011) Examining the effects of community-based sanctions on offender recidivism. Justice Q Short-term effects of sanctioning reform on parole officers’ revocation decisions. Law and Society Review, 45(2), 371400

- Stitzer ML, Jones HE, Tuten M, Wong C (2011) Community reinforcement approach and contingency management interventions for substance abuse. In: Cox WM, Klinger E (eds) Handbook of motivational counseling: goal-based approaches to assessment and intervention with addiction and other problems. Wiley, Chichester, pp 549–569, Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470979952.ch23/summary

- Taxman FS (1998) Reducing recidivism through a seamless system of care: components of effective treatment, supervision, and transition services in the community. Office of National Drug Control Policy, Treatment and Criminal Justice System Conference, Washington, DC, Feb 1998. NCJ 171836

- Taxman FS (2002) Supervision–exploring the dimensions of effectiveness. Fed Probat 66(2):14–27

- Taxman FS (2008a) No illusion, offender and organizational change in Maryland’s proactive community supervision model. Criminol Public Policy 7(2):275–302

- Taxman FS (2008b) To be or not to be: community supervision de´ja` vu. J Offender Rehab 47(3): 250–260

- Taxman FS, Ainsworth S (2009) Correctional milieu: the key to quality outcomes. Vict Offender, 4(4), 334–340

- Taxman FS, Belenko S (2011) Implementing evidence-based practices in community corrections and addiction treatment. Springer, New York: Springer-Verlay

- Taxman FS, Shepardson E, Byrne JM (2004) Tools of the trade: a guide to implementing science into practice. National Institute of Corrections, Washington, DC

- Taxman FS, Thanner M (2004) Probation from a therapeutic perspective: results from the field. Contemp Issues Law 7(1):39–63

- Taxman FS, Thanner M (2006) Risk, need, & responsivity: it all depends. Crime Delinq 52(1):28–51, PMID: 18542715

- Thanner M, Taxman FS (2003) Responsivity: the value of providing intensive services to high-risk offenders. J Subst Abus Treat 24:137–147

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.