This sample British Crime Survey Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW), until 1 April 2012 known as the British Crime Survey (BCS), is a victimization survey of the population resident in households in England and Wales. The primary motive for launching the survey, over 30 years ago, was to assess how much crime went unreported in official police records. Today the survey has a high profile and has become a key social indicator charting trends in crime experienced by the general population. Its quarterly results receive considerable media attention, and politicians debate the implications of its findings.

However, from its inception, the survey was not designed to be merely a social indicator. One of its strengths has been that it has provided a rich source for criminological research and for informing policy development. Analysis of the survey has been instrumental in shedding more light on the nature and circumstances of victimization. The survey has not stood still and has continued to evolve and develop its methodology and content to respond to emerging issues.

The survey was first commissioned by the UK Home Office (the Government department responsible for crime and policing), but responsibility for it has recently transferred to the central Office for National Statistics. This move raises questions about the future role of the survey and whether it can continue to effectively balance its role as a key social indicator on the one hand with a continuing role as an invaluable research tool on the other.

Origins

The Home Office, the Government department responsible for crime and policing in England and Wales, started collecting statistics on crimes recorded by the police over 100 years ago. The numbers of crimes recorded by the police grew inexorably from less than 100,000 crimes per year at the turn of the twentieth century to half a million in the 1950s, a million in the 1960s, and two million in the 1970s. By 1981, over three million crimes a year were recorded by the police. Many criminologists were skeptical that this scale of increase represented a real rise of such magnitude in crime.

The first attempts to derive alternative measures of crime, based on sample surveys of the general population, started to develop in the United States (US) in the late 1960s. The first surveys of this kind were carried out for the US President’s Commission on Crime which in turn led to the establishment of the National Crime Survey (NCS) program and subsequently the National Crime and Victimization Survey (NCVS).

This and the development of small area victimization surveys in the UK inspired analysts working in the Home Office to press for a national victimization survey to be developed. The discussions around the case for such a survey within the Home Office has been outlined by some of those closely involved in the decision back in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Hough et al. 2007). A strong part of the case for the creation of the BCS, as it later became known, was to yield an assessment of what was referred to at the time as the “dark figure” of crime, that is, crimes which escaped official police records. Indeed the first published report of the survey’s findings refers to one of its main aims being to provide an “index of crime as a complement to the figures of (police) recorded offences” (Hough and Mayhew 1983).

The decision to commission a national survey of crime in England and Wales was taken by the Home Office in mid-1981, and the Scottish Home and Health Department (the Government department responsible for crime and policing in Scotland, at the time) decided to fund an extension to cover Scotland shortly thereafter. A contract for data collection was awarded to an independent survey organization, Social and Community Planning Research (SCPR) which has subsequently become the National Centre for Social Research (NCSR).

However, from its beginnings, the survey was conceived as being more than merely an instrument for counting crime. The survey was seen as providing a rich source of data about the characteristics of victims of crime, the nature, and consequences of victimization experiences. This contrasted with the police-recorded statistics which yielded little more than aggregate counts of offences by area. In addition, the survey was able to include questions on public attitudes to crime and crime-related issues, and again, this provided a rich new vehicle for criminological research.

Methodology

An annual technical report covering the survey methodology is produced by the survey contractor each year, and the latest version, at the time of writing, covered the 2010/2011 survey year (Fitzpatrik and Grant 2011). Below, a brief summary of the key aspects of methodology and how it has developed over time can be found.

Population Coverage, Sampling, And Weighting

The BCS was conceived as a survey of the population resident in households and, as such, was never intended to capture the victimization experiences of other groups (e.g., those permanently resident in institutions) or organizations (e.g., commercial victims). The survey was designed to yield results for a nationally representative sample of the adult population (defined as those aged 16 years and over). In more recent years, the sample has been extended to cover the experiences of children aged 10–15 years (see below).

While the survey covered the whole of Britain in its early years, it soon became restricted in its geographical coverage to just England and Wales. Thus, for most of its history, the BCS was something of a misnomer, and following the transfer of responsibility for the survey from the Home Office to the Office for National Statistics (see below), the survey was renamed as the Crime Survey for England and Wales on 1 April 2012 to better reflect its geographical coverage.

Since the first survey in 1982, the CSEW has randomly selected one adult per household sampled to take part in the survey. The sampling frame used to draw the original sample of households/adults has evolved over time from the electoral register (a record of those adults entitled to vote) for the first three rounds of the survey to the small-user Postcode Address File (a record of residential addresses maintained by the Royal Mail) ever since. The sample design has been subject to a number of modifications with high-crime areas over-sampled in the early years when the annual sample size typically ranged between 10,000 and 15,000 adults. The 2000 BCS was the only survey to adopt a fully proportional sample (i.e., with every area selected with probability proportional to size).

Following the expansion of the sample size thereafter, and the need for the survey to yield a number of key estimates at police force area level, the survey has moved again to a disproportionate sampling but this time with less populous (and thus lower crime areas) over-sampled. The sample design has been refined in recent years to move to a partially clustered sample design involving an unclustered sample of addresses being drawn in the most densely populated areas, with more clustered designs in the medium population density and low population density areas.

Throughout the history of the survey, appropriate weighting systems have been developed to adjust for the different selection probabilities involved in the respective designs. An independent review was commissioned by the Home Office in 2009 to examine the impact of the changes in sample design on the reliability of BCS crime trend estimates (Tipping et al. 2010). This showed that no bias had been introduced to the survey from changes in the sample design and that all designs examined had generated estimates of victimization with low levels of variance. The authors concluded that changes in the sample design had not affected the ability of the survey to identify trends in victimization reliably.

Crime Reference Period And Victimization Measures

The data collection period for the first BCS took place in the first few months of 1982 and asked respondents about incidents that had happened since 1 January 1981. For the purpose of analysis and reporting, all incidents occurring in 1982 were excluded so that respondents had a common crime reference period of the 1981 calendar year. A change to the crime reference period was required with the move to a continuous survey, with data collection taking place throughout the year, from 2001/02. The survey then moved to asking respondents about crimes that had been experienced in the 12 months prior to interview. This resulted in the development of a rolling reference period with, for example respondents interviewed in January asked about crimes experienced from the previous January to December, those interviewed in February asked about crimes experienced between the previous February and January of the year of interview, and so on. Respondents were additionally asked for information on the month in which an incident took place or, if they could not recall the exact month, the quarter. This allows analysts to retrospectively splice data from multiple years to construct crime rates on the basis of calendar years if they should wish to do so (see (Tipping et al. 2010).

Since the survey began, the basic approach to obtaining information on victimization experiences has not changed. Respondents are asked a series of screener questions designed to ensure that all incidents of crime within the scope of the survey, including relatively minor ones, are mentioned. The screener questions deliberately avoid using legal terms such as “burglary,” “robbery,” or “assault,” all of which have a precise definition that many respondents will not know. The wording of these questions has been kept consistent since the survey began to ensure comparability across years.

Depending upon individual circumstances, a maximum of 25 screener questions are asked covering:

• Vehicle-related crimes (e.g., theft of vehicle, theft from vehicle, damage to vehicle, bicycle theft)

• Property-related crimes (e.g., whether anything was stolen, whether the property was broken into, whether any property was damaged)

• Experience of personal crimes (e.g., whether any personal property was stolen, whether any personal property was damaged, whether they had been a victim of force or violence or threats)

All vehicle-related and property-related crimes are considered to be household incidents, and respondents are asked about whether anyone currently residing in their household has experienced any incidents within the reference period. For respondents who have moved within the last 12 months, questions on household crimes are asked both in relation to the property they are now living in as well as other places they have lived in the last 12 months. Personal incidents refer to all crimes against the individual and only relate to things that have happened to the respondent personally, but not to other people in the household. Weights are created to allow analysis at either household or personal level.

All incidents identified at the screener questions are then followed through in a series of detailed questions. The first three victimization modules include detailed questions relating to each incident; the last three victim modules are shorter modules, designed to be much quicker to complete to avoid respondent fatigue during the interview. The order in which the victim modules are asked depends on the type of crime – less common crimes are prioritized in order to collect as much detailed information as possible. A total of up to six victimization modules can be completed by each respondent.

Most incidents reported represent one-off crimes or single incidents. However, in a minority of cases, a respondent may have been victimized a number of times in succession. At each screener question where a respondent reported an incident, they are asked how many incidents of the given type had occurred during the reference period. If more than one incident had been reported, the respondent was asked whether they thought that these incidents represented a “series” or not. A series is defined as “the same thing, done under the same circumstances and probably by the same people.”

Where this was the case, only one set of detailed victimization questions are asked in relation to the most recent incident in the series. There are two practical advantages to this approach of only asking about the most recent incident where a series of similar incidents has occurred. First, since some (although not all) incidents classified as a series can be petty or minor incidents (e.g., vandalism), it avoids the need to ask the same questions to a respondent several times over and thus reducing respondent burden. Secondly, it avoids “using up” the limit of six sets of detailed victimization questions on incidents which may be less serious.

In subsequent analysis and reporting, the convention has been for single incidents to be counted once and series incidents to be given a score equal to the number of incidents in the series occurring in the reference period, with an arbitrary top limit of five. This procedure was introduced in order to ensure that the survey estimates are not affected by a very small number of respondents who report an extremely high number of incidents and which are highly variable between survey years. The inclusion of such victims could undermine the ability to measure trends consistently. This sort of capping is consistent with other surveys of crime and other topics. However, the decision to cap series incidents at five has led to some criticism with it being claimed that this has served to mask the extent of chronic victimization and harms experienced by the most frequently victimized (Farrell and Pease 2007).

The first BCS developed an Offence Coding System to enable incidents reported by respondents to be assigned a criminal offence code (e.g., burglary or robbery) that approximated to the way in which incidents were classified by the police. This offence coding process takes place outside of the interview itself using a team of specially trained coders who determine whether what has been reported represents a crime or not and, if so, what offence code should be assigned to it. Apart from some minor changes, the code frame and the instructions to coders for the core survey have remained stable since the first survey.

Mode Of Interview

The 1982 BCS was conducted in respondent’s homes with trained interviewers collecting data via a paper-and-pencil-administered interviewing (i.e., interviewers filled in paper questionnaires by hand with extensive post-interview data keying and editing process). In 1994, the BCS moved to computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) which brought improvements to data quality as it was possible to automatically route respondents through the questionnaire, without relying on interviewers following written instructions, and to incorporate logic and consistency checks on data entered in different parts of the questionnaire. CAPI also allows date calculations and text substitutions which help the interviewer ensure the interview flows smoothly.

The move to laptop computers provided further opportunities for innovation with self-completion modules introduced to cover sensitive topics. The use of self-completion on laptops allows respondents to feel more at ease when answering questions on sensitive topics due to increased confidence in the privacy and confidentiality of the survey.

Self-completion modules were first included in the 1996 BCS to obtain improved estimates of domestic violence (Walby and Allen 2004), and a similar module has been included since the 2004/2005 survey. A paper self-completion module on illicit drug use was included in the 1994 BCS though a change in the way in which these questions were asked when it was reintroduced with CASI means that comparable figures are only available from 1996. A separate annual report on the findings from the drugs self-completion continues to be published by the Home Office with the latest one at the time of writing relating to the 2011/2012 survey year (Home 2012a).

The self-completion modules are restricted to those respondents aged 16–59 years (the decision to exclude those aged 60 and over was an economy measure). In the 2008/2009 survey, a 6-month trial was conducted to examine the feasibility of raising the age limit to 69, but this proved unsuccessful (Bolling et al. 2009).

Regularity Of Survey Fieldwork

Following the first BCS in 1982, a second survey took place in 1984 with fieldwork taking place early that year and with the preceding calendar year (1983) acting as the reference period. Subsequent surveys were repeated on the same basis in 1988, 1992, 1994, 1996, 1998, 2000, and 2001.

In the late 1990s, the value of the survey for policy purposes was recognized by the Home Office which planned to move the survey onto an annual cycle and to increase substantially its sample size. These moves were designed to as a means of increasing the frequency with which survey-based estimates could be published, while the increase in sample size was motivated by a desire to increase the precision of certain estimates. The latter was related, in part, for the need to use the survey to provide key performance indicators to assess the performance of the police.

The Home Office commissioned an independent review by leading experts in survey methodology and this reported in 2000 (Lynn and Elliot 2000). They recommended a number of major changes to the survey including:

• A move to a continuous fieldwork with the crime reference period being the 12 months ending with the most recent completed calendar month

• Expansion of the sample to obtain a minimum achieved sample of 600 or 700 interviews per year in each police force area

• Introduction of nonresponse weighting to incorporate both sample weighting (which was already being done) and calibration to population totals (i.e., to correct for potential additional nonresponse bias).

These recommendations were accepted, and the change took place with the 2001/2002 survey. There being 43 territorial police forces in England and Wales, this required a large increase in the annual sample size of the survey from around 20,000 in 2000 to around 33,000 in the 2001/2002 survey. Over the next few years, further demands for the BCS to provide key performance indicators led to further boosts to the annual sample size, which increased to over 36,000 in 2002/2003, some 38,000 in 2003/2004, and over 45,000 by 2004/2005.

More recently, it has been announced that due to cuts in government funding, the sample size of the survey will reduce with the 2012/2013 survey cut back to a sample of around 35,000 per year (Home 2012b). Nevertheless, it is a sign of the importance of the survey and the value in which it is held that in a period when other surveys have been stopped, the BCS continues to run with a sample some three times larger than the first survey in 1982.

Extension Of Survey To Children

The survey was restricted to the experiences of adults except for a one-off exercise in 1992 when a separate sample of children aged 12–15 were interviewed (Aye Maung 1995). This previous exercise did not attempt to replicate the methodology of the adult survey or to combine estimates from the adult and child surveys.

Following recommendations in two related reviews of crime statistics (Smith 2006; Statistics Commission 2006), the BCS was extended to children aged 10–15 from January 2009. The Home Office commissioned methodological advice on the feasibility of extending the survey to children (Pickering and Smith 2008), and following an extensive period of development and testing work during 2008, live data collection started in January 2009.

Children aged 10–15 are interviewed in households that have taken part in the main survey; where an eligible child is identified (according to age), one is selected at random to take part. Extending the survey to encompass children’s experience of crimes raised some difficult issues with regard to classifying criminal incidents; e.g., minor incidents that are normal within the context of childhood behavior and development can be categorized as criminal when existing legal definitions of offences are applied. Four different methods for counting crime against children were examined and subject to user consultation (Millard and Flatley 2010). Following consultation, two main measures were adopted. The first, called the “broad measure,” is one in which all incidents that are in law a crime are counted. This will include minor offences between children and family members that would not normally be treated as criminal matters. The second, referred to as a “preferred measure,” is a more focused method which takes into account factors identified as important in determining the severity of an incident (as judged by focus groups with children).

Methodological differences between the adult and children’s survey mean that direct comparisons cannot be made between the adult and child victimization data, although these estimates are now presented in the published quarterly crime statistics (Office for National Statistics 2012) to provide a better understanding of victimization experiences among adults and children resident in households.

Methodological Limitations

The CSEW is viewed asa gold-standard survey of its kind in terms of its methodology and response rate (the survey has continued to obtain a response rate of 75 % during the last decade when other voluntary household surveys in the UK have experienced falling response rates). However, as with other sample surveys, there are a number of inherent methodological limitations, some of which have already been touched on above.

The most obvious of these relate to sampling error and the inherent imprecision around survey estimates. There are other sources of survey error, such as related to respondents’ ability to recall events and report them to the interviewer accurately. Some incidents may be forgotten or events beyond the reference period brought into scope. Respondents may be embarrassed or unwilling to disclose some information to interviewers. Questions may be misinterpreted by respondent, and interviewers themselves may make mistakes in recording information given to them, and coders may make errors of interpretation when assigning incidents to offence codes. The survey contractors go to great lengths to minimize these errors through careful training of interviewers, testing of questions, and quality assurance of all aspects of the survey process.

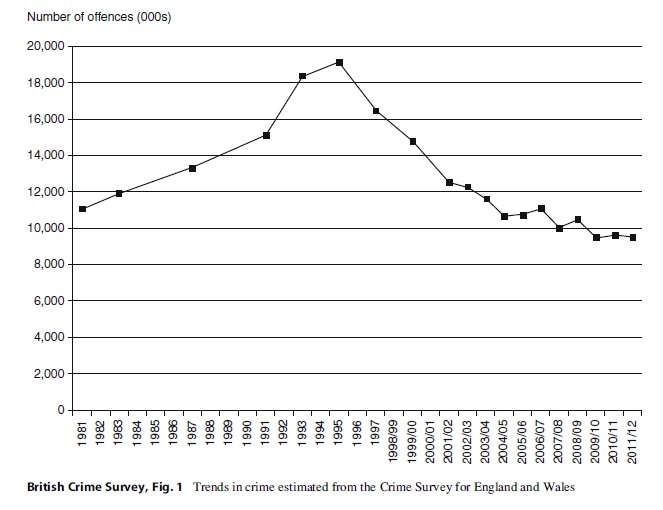

The Influence Of The Survey On Criminological Thinking

The CSEW is now part of the UK National Statistics system with results from the survey reported on a quarterly basis alongside the police-recorded crime figures to provide a complementary and more comprehensive account of crime in England and Wales (Office for National Statistics 2012). The survey charted a rise in the volume of crimes covered by the survey through the 1980s reaching a peak in the mid-1990s. In line with the experience of many other industrialized economies, the survey described a fall in crime over the next 10–15 years with a generally stable trend in more recent years. However, the survey has had wider influence on criminological thinking, and it is this which is touched on below.

Victimization Risks Including Repeat And Multiple Victimization

The first BCS report highlighted the relative rarity of serious criminal victimization but also the fact that a small segment of the general population was particularly prone to falling victim (Hough and Mayhew 1983). At the time, the fact that it was younger adults, rather than the elderly, who were more likely to be victims of crime was a striking finding.

More detailed analysis of the dimensions of risk followed (Gottfredson 1984) including area-based analysis. For example, secondary analysis of the 1982 BCS revealed significant differences between high-and low-crime areas (Trickett et al. 1992). This showed a strong relationship such that the number of victimizations per victim rose markedly as the area crime rate increased. Further analysis showed similar patterns during the 1980s with a small number of areas hosting a disproportionate amount of crime (Hope and Hough, 1988). Further work examining the extent of repeat and multiple victimization includes one study of the BCS showing that 70 % of all incidents were reported by just 14 % of respondents who were multiple victims (Farrell and Pease 1993).

Such studies were influential in suggesting that a large proportion of all crime might be prevented if repeat or multiple victimization could be reduced and that crime prevention policy should focus on reducing the repeat victimization experienced by the most vulnerable people and in the most vulnerable places.

Sexual And Domestic Violence

The BCS has been groundbreaking in its approach to the measurement of sexual and domestic violence. A self-completion module on domestic violence was included in the 1996 BCS (Mirrlees-Black 1999) and on sexual victimization in both the 1998 and 2000 surveys. The 2001 BCS included a more detailed self-completion questionnaire on both these topics. It was designed to yield national estimates of the extent and nature of domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking including the first ever such estimates of sexual assault against men (Walby and Allen 2004).

This showed that interpersonal violence affected around one-third of the population at some time in their lives with women suffering higher levels of victimization than men. It also demonstrated that such victims suffered high levels of repeat victimization, in particular of domestic violence. While these findings were not surprising to experts in the field, they quantified a phenomenon which helped to challenge others to seek to tackle these forms of violence.

Fear Of Crime And Perceptions Of Crime And Antisocial Behavior

Fear of crime has been a topic included in the survey from its very beginnings. It is a concept which is complex and difficult to measure. Over the years, the survey has deployed a range of questions, and researchers have sought to explain the key drivers and relationships (see, e.g., Allen 2006). Other researchers have used BCS questions to explore the frequency and intensity of fear of crime (Farrall and Gadd 2004). It has been suggested that few people experience specific events of worry on a frequent basis and that “worry about crime” is often best seen as a diffuse anxiety about risk, rather than any pattern of everyday concerns over personal safety (Gray et al. 2011).

The survey has also been used to describe two types of “perception gap”: one related to differences between what is happening to crime nationally and in the local area and, the second, the difference between perceptions of crime and actual crime levels. New questions added to the 2008/ 2009 survey revealed that the perception gap between changes nationally and in the local area were greater for the more serious violent (and therefore rarer) crimes and smaller for acquisitive crimes suggesting personal experience was more likely to play a part in the perceptions of the more common crimes while perceptions of rarer crime types are likely to be influenced by media reporting. In addition, analysis of small area police-recorded crime data showed a clear linear relationship between actual levels of crime and perceptions of the comparative level of crime in the local area (Murphy and Flatley 2009).

Antisocial behavior has become a major focus for government policy and practitioners since the late 1980s. Questions were added to the 1992 BCS to ask people about their perceptions of antisocial behavior in their area, and these have been revised and expanded over time to include personal experiences as well as perceptions and what such perceptions were based on (see, e.g., Upson 2006).

Public Attitudes To The Police And Criminal Justice System

The coverage of policing issues has expanded in the survey over time with specific modules of questions being included on contact with the police and public attitudes to the police (see, e.g., Skogan 1994). Analysis of the experience of ethnic minorities with the police has also been a focus of BCS analysis (see, e.g., Clancy et al. 2001). In more recent years, the focus on neighborhood policing and on police performance has led to questions being more routinely included on police visibility and public attitudes towards the police (see, e.g., Allen et al. 2006; Moon and Flatley 2011).

The BCS included questions on public attitudes to sentencing in the 1982 and in a number of subsequent rounds of the survey which has made an important contribution to the understanding of such issues. The 1996 BCS included a range of specific questions on attitudes to punishment and revealed a rather jaundiced view of sentencers and sentencing thinking them to be too lenient (Hough and Roberts 1998). This analysis showed that public disaffection was partly a result of ignorance of judicial practice and, ironically, when people were asked to prescribe sentences for actual cases, their sentencing tended to be in line with current sentencing practice.

New Types Of Crime

Throughout its life course, the survey has sought to adapt to emerging issues, and below are some examples of how the survey has evolved to meet changing information needs.

Following the Stephen Lawrence inquiry in 1999, the survey included questions on racially motivated crimes, and in recent years, the module of questions has been expanded to ask victims of crime if they thought the crime had been religiously motivated. Other strands of “hate crime” have also been added to the survey more recently (see, Lader 2012).

Responding to changes in technology, a mobile phone theft module was added to the 2001/2002 survey to examine levels of such thefts. Subsequent analysis has explored the extent of mobile phone theft which showed the increased risk of such victimization among children and young adults (Hoare 2007).

Similarly, a module covering fraud and technology crimes was first introduced in the 2002/2003 BCS. This covered the extent to which people had been victims of debit and credit card fraud, their computers had been infected with viruses or hacked into, or they had been sent harassing emails. An Identity Theft module was introduced to the BCS in 2005/2006 (Hoare and Wood 2007).

Future Directions

As has been described above, responsibility for the CSEW has recently transferred to the Office for National Statistics. In a piece written to mark the 25th anniversary of the birth of the BCS, the founders of the survey described the tensions within the Home Office between the researchers (who promoted the survey) and the statisticians (who were more skeptical of its value).

As shown in Fig. 1, the survey has charted the rise in crime from the early 1980s through to the mid-1990s and the subsequent crime drop that has also been seen across other developed economies. As the survey has become institutionalised as a key social statistic in the UK, responsibility for it has passed from the researchers to the statisticians (first, following a structural reorganization in the Home Office in April 2008 and more recently with the move to ONS). Perhaps inevitably this has resulted in a subtle shift in priorities. However, up to now the survey has managed to combine its social indicator and research tool functions.

One of the key challenges for the ONS going forward is to ensure the continuation of both these functions to ensure the rich legacy of the survey as key resource for criminological enquiry continues.

Bibliography:

- Allen J (2006) Worry about crime in England and Wales: findings from the 2003/04 and 2004/05 British Crime Survey, Home Office Online Report, 15 June 2006

- Allen J, Patterson A, Edmonds S, Smith D (2006) Policing and the criminal justice system – public confidence and perceptions: findings from the 2004/05 British Crime Survey. Home Office, London, Home Office Online Report 07/06

- Aye Maung N (1995) Young people, victimization and the police: British crime survey findings on experiences and attitudes of 12 to 15 years old. Home Office, London, Home Office Research Study 140

- Bolling K, Grant C, Donovan J-L (2009) 2008–09 British crime survey (England and Wales) technical report, vol I. Home Office/BMRB Social Research, London

- Clancy A, Hough M, Aust R, Kershaw C (2001) Crime, policing and justice: the experience of ethnic minorities. Findings from the 2000 British Crime Survey. Home Office, London, Home Office Research Study 223

- Farrall S, Gadd D (2004) The frequency of the fear of crime. Br J Criminol 44(1):127–132

- Farrell G (1999) Multiple victimization: its extent and significance. Int Rev Victimol 2:85–102

- Farrell G, Pease K (1993) Once Bitten, Twice Bitten: Repeat Victimisation and its Implications for Crime Prevention, Police Research Group, London, Home Office Crime Prevention Unit Paper 46

- Farrell G, Pease K (2007) The sting in the tail of the British crime survey: multiple victimisations. In: Hough M, Maxfield M (eds) Surveying crime in the 21st century, crime prevention studies, vol 22. Criminal Justice Press Monsey, New York

- Fitzpatrik A, Grant C (2011) The 2010/11 British crime survey technical report volume 1. Home Office/TNSBMRB, London

- Gottfredson M (1984) Victims of crime: the dimensions of risk. HMSO, London, Home Office Research Study No 81

- Gray E, Jackson J, Farrall S (2011) Feelings and functions in the fear of crime: applying a new approach to victimization insecurity. Br J Criminol 51(1):75–94

- Hoare J (2007) Mobile phones: ownership and theft. In Flatley J (ed) Mobile phone theft, plastic card and identity fraud: findings from the 2005/06 British Crime Survey, Supplementary Volume 2 to Crime in England and Wales 2005/06, Home Office Statistical Bulletin 10/07

- Hoare J, Wood C (2007) Plastic card and identity fraud. In Flatley J (ed) Mobile phone theft, plastic card and identity fraud: findings from the 2005/06 British Crime Survey Supplementary Volume 2 to Crime in England and Wales 2005/06, Home Office Statistical Bulletin 10/07 (2007)

- Home Office (2012a) Drug misuse declared: findings from the 2011/12 crime survey for England and Wales. Home Office Online Report

- Home Office (2012b) Consultation on changes to the BCS sample design, Home Office online report

- Hope T, Hough M (1988) Area crime and incivilities: a profile from the British crime survey. In: Hope T, Shaw M (eds) Communities and crime reduction. HMSO, London

- Hough M, Mayhew P (1983) The British Crime Survey: first report: Home Office Research Study No. 76. HMSO, London

- Hough M, Maxfield M, Morris B, Simmons J (2007) The British Crime Survey over 25 years: progress, problems and prospects. In: Hough M, Maxfield M (eds) Surveying crime in the 21st century, crime prevention studies, vol 22. Criminal Justice Press Monsey, New York

- Hough M, Roberts J (1998) Attitudes to punishment: findings from the British Crime Survey. Home Office,

- Mirrlees-Black C (1999) Domestic violence: findings from a new British Crime Survey self-completion questionnaire. Home Office, London, Research Study 191

- Moon D, Flatley J (eds) (2011) Perceptions of crime, engagement with the police, authorities dealing with anti-social behaviour and Community Payback: findings from the 2010/11 British Crime Survey, supplementary volume 1 to crime in England and Wales 2010/11, Home Office Statistical Bulletin 18/11

- Murphy R, Flatley J (2009) Perceptions of crime. In Moon D, Walker A (eds) Perceptions of crime and anti-social behaviour: findings from the 2008/09 British Crime Survey supplementary volume 1 to crime in England and Wales 2008/09, Home Office Statistical Bulletin 17/09

- Office for National Statistics (2012) Crime in England and Wales, quarterly. First Release to March 2012; ONS Statistical Bulletin, London

- Pickering K, Smith P (2008) British Crime Survey: options for extending the coverage to children and people living in communal establishments. Home Office, London

- Skogan W (1994) Contacts between police and public: findings from the 1992 British Crime Survey. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, Home Office Research Study 134

- Smith A (2006) Crime statistics: an independent review. Independent report. Home Office, London

- Statistics Commission (2006) Crime statistics: user perspectives. Statistics Commission Report No. 30. Statistics Commission, London

- Tipping S, Hussey D, Wood M, Hales J (2010) British Crime Survey: methods review 2009 final report. National Centre for Social Research, London

- Trickett A, Osborn D, Seymour J, Pease K (1992) What is different about high crime areas? Br J Criminol 32(1):81–89

- Upson A (2006) Perceptions and experience of anti-social behaviour: findings from the 2004/05 British Crime Survey, Home Office Online Report 21/06

- Walby S, Allen J (2004) Home Office Research Study 276. Domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking: findings from the British Crime Survey London, Home Office Research Study 179

- Lader D (2012) The extent of and perceptions towards hate crime. In Smith K (ed) Hate crime, cyber security and the experience of crime among children: findings from the 2010/11 British Crime Survey: supplementary volume 3 to crime in England and Wales 2010/11, Home Office Statistical Bulletin 06/12

- Lynn P, Elliot D (2000) The British Crime Survey: a review of methodology. National Centre for Social Research, London

- Millard B, Flatley J (ed) (2010) Experimental statistics on victimization of children aged 10 to 15: findings from the British Crime Survey for the year ending December 2009 England and Wales, Home Office Statistical Bulletin 11/10

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.