This sample CCTV and Crime Prevention Research Paper is published foreducational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing yourassignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic ataffordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Western countries are experiencing a substantial increase in the use of closed-circuit television (CCTV) surveillance cameras to prevent crime in public places. Amid this expansion and the associated public expenditure, as well as concerns about their effectiveness and social costs, there is an increasing need for an evidence-based approach to inform CCTV policy and practice. This research paper reports on an updated Campbell Collaboration systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of CCTV on crime in public places. The results suggest that CCTV has a modest but significant effect on reducing crime. This overall result was largely driven by the effectiveness of CCTV schemes in car parks, which were targeted at vehicle crimes and included other interventions such as improved lighting, fencing, and security guards. Nonsignificant effects on crime were observed in the other public settings in which CCTV schemes were evaluated: city and town centers, public housing communities, and public transportation facilities.

CCTV has become a widely popular and commonplace technology that is being deployed to help make public (and private) places safer from crime. Across many cities and towns, it is touted as a panacea to crime. But it is not without its controversies, and many questions remain about its ability to reduce crime. This research paper reports on the results of a systematic review – incorporating meta-analytic techniques – to assess the scientific evidence on the effectiveness of CCTV to prevent crime in public places.

In recent years, there has been a marked and sustained growth in the use of CCTV surveillance cameras to prevent crime in public places in many Western nations. The United Kingdom in particular is on the cusp of becoming, in the words of some, a “surveillance society,” with upward of a million or more cameras in public places (Norris 2007).

There are no national estimates as yet on the number of CCTV cameras in the United States, but local accounts indicate that they are being installed at an unprecedented rate and their popularity is not limited to large urban centers. Some of this increased use in the United States has come about in an effort to aid the police in the detection and prevention of terrorist activities, especially in New York City and other metropolises. However, the prevention of crime remains an important aim of these CCTV systems. Similar claims about the purpose of public CCTV have been made in the United Kingdom. There are also signs that other countries are increasingly experimenting with CCTV to prevent crime in public places. Evaluation studies of public CCTV schemes have been carried out recently in a number of European countries, including Germany, Norway, and Sweden, as well as in Australia, Canada, and Japan. Many of these countries have not previously used CCTV in public places, let alone evaluated its effects on crime.

The growth in CCTV has come with a huge price tag. In the United Kingdom, CCTV has been and continues to be the single most heavily funded crime prevention measure operating outside of the criminal justice system. In the United States, estimates suggest that public expenditure on CCTV may be as much as $100 million each year (Savage 2007).

There has been much debate about the effectiveness of CCTV in preventing crime and hence on the wisdom of spending such large sums of money. A key issue is to what extent funding for CCTV, especially in the United Kingdom and the United States, has been based on high quality scientific evidence demonstrating its effectiveness in preventing crime (Welsh and Farrington 2009a, b).

Methods

The methodology employed in our systematic review follows the conventions set out by the Campbell Collaboration. Evaluations were included in the systematic review if they met a number of criteria, including if CCTV was the main intervention, if there was an outcome measure of crime, and if the evaluation design was of high methodological quality. At a minimum, high quality evaluation designs involve before and after measures of crime in experimental and comparable control areas. Control areas are needed to assess what would have happened in the absence of CCTV and to counter threats to internal validity.

Extensive search strategies were employed to locate studies meeting the criteria for inclusion, including searches of electronic bibliographic databases, searches of literature reviews on the effectiveness of CCTV on crime, and contacts with leading researchers. Altogether, 44 studies were found that met our inclusion criteria.

In order to carry out a meta-analysis, a comparable measure of effect size and an estimate of its variance are needed in each program evaluation (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). In the case of CCTV evaluations, the measure of effect size had to be based on the number of crimes in the experimental and control areas before and after the intervention. This is because this is the only information that was regularly provided in these evaluations.

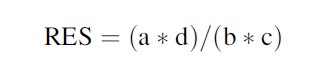

The “relative effect size” or RES is used to measure effect size. The RES is intuitively meaningful because it indicates the relative change in crimes in the control area compared with the experimental area. For example, RES ¼ 2 indicates that the change in the control areas is twice as large as the experimental areas. This value could be obtained, for example, if crimes doubled in the control area and stayed constant in the experimental area, or if crimes decreased by half in the experimental area and stayed constant in the control area, or in numerous other ways. The RES is computed from the pre and post-CCTV crime counts in the control and experimental areas. The equation is as follows:

where a and b are the pre- and post-CCTV crime counts for the experimental areas, respectively, and c and d are the pre- and post-CCTV crime counts for the control areas, respectively.

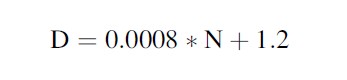

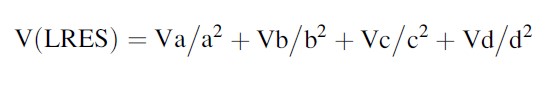

The meta-analysis was performed on the logged values of RES with the final results converted back into the original scale by taking the antilog. In order to perform the meta-analysis, the variance of each logged RES is needed. If we assume that the crime counts are Poisson distributed, then the variance is 1/a + 1/b + 1/c + 1/d. This assumption is plausible because 30 years of mathematical models of criminal careers have been dominated by the assumption that crimes can be accurately modeled by a Poisson process (Piquero et al. 2007). In a Poisson process, the variance of the number of crimes is the same as the number of crimes (i.e., v = n). However, the large number of changing extraneous factors that influence the number of crimes may cause overdispersion; that is, where the variance of the number of crimes exceeds the number of crimes. Farrington et al. (2007) estimated the overdispersion (D) in crime counts as follows:

D increased linearly with N and was correlated 0.77 with N. The mean number of crimes in an area in the CCTV studies was about 760, suggesting that the mean value of D was about 2. However, this is an overestimate because the monthly variance is inflated by seasonal variations, which do not apply to N and VAR. Nevertheless, in order to obtain a conservative estimate, V(LRES), which is the variance of LRES (and is distinguished from Va, which is the variance of a), calculated from the usual formula above was multiplied by D (estimated from the above equation) in all cases. Specifically,

where Va/a = 0.0008*a + 1.2

This is our best available estimate of the degree of over-dispersion in area-based crime prevention studies.

Forty-one of the 44 studies could be used in the meta-analysis. RES effect sizes could not be calculated for three studies because numbers of crimes were not reported in the city and town center schemes in Ilford or (for the control area) Sutton or for the public housing scheme in Brooklyn. (Throughout this research paper, the included studies are identified by the name of the city or town where they were implemented. Full references can be obtained from the authors’ Campbell Collaboration systematic review, which is available at: http://www.campbellcollaboration. org/crime_and_justice/index.php.)

Findings

Setting

City and town centers. Twenty-two evaluations were carried out in city and town centers. Seventeen of these were carried out in the United Kingdom, three in the United States, one in Sweden, and one in Norway. Only some of the studies reported the coverage of the CCTV cameras. For example, in the Newcastle-uponTyne and Malmo¨ studies, the camera coverage of the target or experimental area was 100 %. Many more studies reported the number of cameras used and their features (e.g., pan, tilt, zoom). Information on camera coverage is important because if a large enough section of the target area or even high crime locations in the target area are not under surveillance, the impact of CCTV may be reduced.

Most of the evaluations that reported information on the monitoring of the cameras used active monitoring, which means that an operator watched monitors linked to the cameras in real time. Passive monitoring involves watching tape recordings of camera footage at a later time. In some of the schemes, such as Newcastle and Birmingham, police carried out active monitoring. But more often it was carried out by security personnel who had some form of communication link with police (e.g., by a one-way radio or direct line telephone).

On average, the follow-up period in the 22 evaluations was 15 months, ranging from a low of 3 months to a high of 60 months. Six programs included other interventions in addition to the main intervention of CCTV. For example, in the Doncaster program, 47 “help-points” were established within the target area to aid the public in contacting the main CCTV control room. Four other studies used notices of CCTV to inform the public that they were under surveillance, but CCTV notices do not necessarily constitute a secondary intervention. A couple of the evaluations used multiple experimental areas (e.g., police beats), meaning that the CCTV intervention was quite extensive in the city or town center. Multiple control areas (e.g., adjacent police beats, the remainder of the city) were used in many more of the evaluations. The most comparable control areas were chosen for analysis. Where control and adjacent areas were used, control areas were analyzed.

The city and town center CCTV evaluations showed mixed results in their effectiveness in reducing crime. Ten of the 22 evaluations were considered to have a desirable effect on crime, 5 were considered to have an undesirable effect, and 1, the multisite British evaluation by Sivarajasingam et al. (2003), was considered to have both (desirable effects according to emergency department admissions and undesirable effects according to police records). The remaining six evaluations were considered to have a null (n=5) or uncertain (n=1) effect on crime. Schemes usually showed evidence of no crime displacement rather than displacement or diffusion of benefits.

As an example, in the program evaluated by Armitage et al. (1999), an unknown number of cameras were installed in the town center of Burnley, England. The experimental area consisted of police beats in the town center with CCTV coverage. Two control areas were used. The first comprised those police beats that shared a common boundary with the beats covered by CCTV. The second control area consisted of other police beats in the police division. The first control area was more comparable to the experimental area and was the one used in our analysis. After 12 months, the experimental area, compared with the two control areas, showed substantial reductions in violent crime, burglary, vehicle crime, and total crime. For example, total incidents of crime fell by 28 % in the experimental area compared with a slight decline of 1 % in the first control area and an increase of 10 % in the second control area. The authors found evidence of diffusion of benefits for the categories of total crime, violent crime, and vehicle crime, and evidence of territorial displacement for burglary.

In pooling the data from the 20 studies for which effect sizes could be calculated, there was evidence that CCTV led to a small but nonsignificant reduction in crime in city and town centers. The weighted mean effect size was a RES of 1.08 (CI 0.97–1.20), which corresponds to a 7 % reduction in crimes in experimental areas compared with control areas. However, when these 20 studies were disaggregated by country, the 15 British studies showed a slightly larger effect on crime (a 10 % decrease; RES = 1.11, CI 0.98–1.27, ns), while the five others showed no effect on crime.

An analysis of heterogeneity showed that the 20 effect sizes were significantly heterogeneous (Q = 143.9, df = 19, p < 0.0001). This means that the differences were not simply a matter of sampling error. The 15 UK studies were also significantly heterogeneous (Q =118.6, df =14, p < 0.0001), as were the five other studies (Q=14.02, df=4, p= 0.007). Therefore, random effects models that assume study-level variability were used in calculating weighted mean effect sizes.

Public housing. Nine evaluations were carried out in public housing. Seven were carried out in the United Kingdom and two in the United States. Camera coverage ranged from a low of 9 % (in Dual Estate) to a high of 87 % (in Northern Estate) in the six evaluations that reported this information. Active monitoring was used in all of the schemes, with monitoring in the Brooklyn evaluation conducted by police. In the six British schemes evaluated by Gill and Spriggs (2005), security personnel who monitored the cameras had some form of communication link with police (e.g., a one-way or two-way radio). On average, the follow-up period in the nine evaluations was 12 months, ranging from a low of 3 months to a high of 18 months. Only three schemes included other interventions in addition to the main intervention of CCTV. These involved improved lighting and youth inclusion projects.

The public housing CCTV evaluations showed mixed results in their effectiveness in reducing crime. Three of the nine evaluations were considered to have a desirable effect on crime, two had an undesirable effect, three had an uncertain effect, and one had a null effect. Only five schemes measured diffusion of benefits or crime displacement, and in each case it was reported that displacement and diffusion did not occur.

In pooling the data from the eight studies for which effect sizes could be calculated, there was evidence that CCTV led to a small but nonsignificant reduction in crime in public housing. The weighted mean effect size was a RES of 1.07 (CI 0.83–1.39), which corresponds to a 7 % reduction in crimes in experimental areas compared with control areas. The eight effect sizes were significantly heterogeneous (Q= 47.94, df=7, p < 0.0001).

The evaluation by Williamson and McLafferty (2000) in Brooklyn, New York, the only one that could not be included in the metaanalysis, is somewhat representative of CCTV’s rather negligible effect on crime in public housing. The housing community that received the intervention (Albany project) did not show any change in the total number of police-recorded crimes, either inside the project or inside a 0.1 mile buffer zone (established to measure crime displacement or diffusion of benefits), while total crime in the control community (Roosevelt project) dropped by 5 % inside the project and 4 % inside the 0.1 mile buffer zone. When total crime was disaggregated, a desirable program effect was observed for major felonies in both experimental and control projects. However, the authors note that, “the substantial decrease in major felonies around both public housing projects seems to be part of a larger downward trend that was occurring not only in Brooklyn but across New York City in the late 1990s” (Williamson and McLafferty 2000, p. 7). Furthermore, the authors’ investigation of the occurrence of crime displacement or diffusion of benefits concluded that there was “no clear evidence” of either, “as the change in crime around the two housing projects does not vary predictably with distance” (p. 7).

Public transport. Four evaluations were carried out in public transportation systems. All of them were conducted in underground railway systems: three in the London Underground and one in the Montreal Metro. None of the studies reported on the percentage of the target areas covered by the cameras, but most did provide information on the number of cameras used. For example, in the Montreal program a total of 130 cameras (approximately 10 per station) were installed in the experimental stations. Each of the schemes involved active monitoring on the part of police; in the London Underground, this meant the British Transport Police.

With the exception of the Montreal program, each evaluation included other interventions in addition to CCTV. In the first Underground scheme, special police patrols were in operation prior to the installation of CCTV. For the two other Underground schemes, some of the other interventions included passenger alarms, kiosks to monitor CCTV, and mirrors. For each of these three Underground schemes, CCTV was, however, the main intervention. The follow-up periods ranged from a low of 12 months to a high of 32 months.

Overall, CCTV programs in public transportation systems present conflicting evidence of effectiveness: two had a desirable effect, one had no effect, and one had an undesirable effect on crime. However, for the two effective programs in the London Underground (southern sector and northern line), the use of other interventions makes it difficult to say with certainty that it was CCTV that caused the observed crime reductions, although in the first of these programs CCTV was more than likely the cause. Only two of the studies measured diffusion of benefits or crime displacement, with one showing evidence of diffusion and the other showing evidence of displacement.

In pooling the data from the four studies, there was evidence that CCTV led to a sizable but nonsignificant reduction in crime in public transport. The weighted mean effect size was a RES of 1.30 (CI 0.87–1.94), which corresponds to a 23 % reduction in crimes in experimental areas compared with control areas. The substantial reduction in robberies and thefts in the first Underground evaluation (an overall 61 % decrease) was the main reason for this large average effect size over all four studies. The four effect sizes were significantly heterogeneous (Q = 30.94, df = 3, p < 0.0001).

Car parks. Six CCTV evaluations met the criteria for inclusion and were conducted in car parks (parking lots). All of the programs were implemented in the United Kingdom between the early 1980s and early 2000s. Camera coverage was near 100 % in the two schemes that reported on it. All of the schemes, with the exception of one that did not provide data, involved active monitoring on the part of security staff. The large-scale, multisite Hawkeye scheme evaluated by Gill and Spriggs (2005) also included a radio link with the British Transport Police.

Each of the programs supplemented CCTV with other interventions, such as improved lighting, painting, fencing, payment schemes, and security personnel. In Coventry, for example, improved lighting, painting, and fencing were part of the package of measures implemented to reduce vehicle crimes. In each program, however, CCTV was the main intervention. The follow-up periods ranged from a low of 10 months to a high of 24 months.

Five of the car park programs had a desirable effect and one had an undesirable effect on crime, with vehicle crimes being the exclusive focus of five of these evaluations. For example, Tilley (1993) evaluated three CCTV programs in car parks in the following UK cities: Hartlepool, Bradford, and Coventry. Each scheme was part of the British Government’s Safer Cities Programme, a large-scale crime prevention initiative that operated from the late 1980s to mid-1990s. In Hartlepool, CCTV cameras were installed in a number of covered car parks and the control area included a number of non-CCTV-covered car parks. Security personnel, notices of CCTV, and payment schemes were also part of the package of measures employed to reduce vehicle crimes. Twenty-four months after the program began thefts of and from vehicles had been substantially reduced in the experimental car parks compared with the control car parks. A 59 % reduction in thefts of vehicles was observed in the experimental car parks compared with a 16 % reduction in the control car parks. Tilley (1993, p. 9) concluded that, “The marked relative advantage of CCTV covered parks in relation to theft of cars clearly declines over time and there are signs that the underlying local trends [an increase in car thefts] begin to be resumed.” The author suggested that the displacement of vehicle thefts from covered to non-covered car parks occurred. Most studies did not measure either diffusion of benefits or crime displacement.

The RESs showed a significant and desirable effect of CCTV for five of the schemes. In the other scheme (Guildford), the effect was undesirable, but the small number of crimes measured in the before and after periods meant that the RES was not significant. When all six effect sizes were combined, the overall RES was 2.03 (CI 1.39–2.96, p=0.0003), meaning that crime decreased by half (51 %) in experimental areas compared with control areas. This indicates a very large and highly significant desirable effect of CCTV on vehicle crimes in car parks. The six effect sizes were significantly heterogeneous (Q=31.93, df=5, p < 0.0001).

Other settings. Three of the 44 evaluations took place in other public settings: two in residential areas and one in a hospital. It was considered necessary to categorize these three schemes separately from the others because of the differences in the settings in which these three schemes were implemented as well as their small numbers.

There were some notable differences between the two residential schemes. The City Outskirts scheme was implemented in an economically depressed area on the outskirts of a Midlands city, while the Borough scheme was implemented throughout a southern borough of mixed affluence. Camera coverage was quite good in City Outskirts (68%), but in Borough it was considered low. Gill and Spriggs (2005) noted that this was due in large measure to the use of redeployable cameras in Borough, while fixed cameras were used in City Outskirts. Other interventions were used in City Outskirts, but not in Borough. Evaluations of the two schemes also found contrasting effects on crime: a significant desirable effect in City Outskirts (a 25 % decrease) and a nearly significant undesirable effect in Borough (a 25 % increase).

The one evaluation of CCTV implemented in a city hospital showed that it produced a desirable but nonsignificant effect on crime (RES=1.38, CI 0.80–2.40), corresponding to a 28 % decrease in crime in the experimental area compared with the control area. Among some of the scheme’s distinguishing features, camera coverage was high (76%), active monitoring was used, there was a direct line between the camera operators and police, and other interventions were implemented, including improved lighting and police operations.

Crime Type

The major crime types that were reported were violence (including robbery) and vehicle crimes (including thefts of and from vehicles). Violence was reported in 23 evaluations, but CCTV had a desirable effect in reducing violence in only three cases (Airdrie, Malmo, and Shire Town). Overall, there was no effect of CCTV on violence (RES=1.03, CI 0.96–1.10, ns). The 23 effect sizes were not significantly heterogeneous (Q=30.87, df =22, n.s.).

Vehicle crimes were reported in 22 evaluations, and CCTV had a desirable effect in reducing them in ten cases: in five of the six car park evaluations (all except Guildford), in three city or town center evaluations (Burnley, Gillingham, and South City), and in City Outskirts and City Hospital. Over all 22 evaluations, CCTV reduced vehicle crimes by 26% (RES =1.35, CI 1.10–1.66, p=0.004). The 22 effect sizes were significantly heterogeneous (Q =115.1, df =21, p < 0.0001). The greatest effect was in the largescale, multisite Hawkeye study, but there was a significant effect even if this study was excluded (RES=1.28, corresponding to a 22 % decrease in crimes).

Country Comparison

Of the 41 evaluations that were included in the meta-analysis, the overwhelming majority of them were carried out in the United Kingdom (n =34). Four were from the United States and one each from Canada, Norway, and Sweden. When the pooled meta-analysis results were disaggregated by country, there was evidence that the use of CCTV to prevent crime was more effective in the United Kingdom than in other countries. In the British studies, CCTV had a significant desirable effect, with an overall 19 % reduction in crime (RES =1.24, CI 1.10–1.39, p = 0.0005). The British studies were significantly heterogeneous (Q =350.5, df =33, p < 0.0001). In the other studies, CCTV showed no desirable effect on crime (RES=0.97, CI 0.86–1.09, ns). The other studies were also significantly heterogeneous (Q= 14.51, df=6, p=0.024). Importantly, the significant results for the British studies were largely driven by the effective programs in car parks.

Key Issues/Controversies

Von Hirsch (2000) argues that there are two major issues that confront the “proper uses and limits” of surveillance for crime prevention in public places. The first issue pertains to privacy concerns. This can be expanded to include other social costs that may infringe on public interests or violate legal or constitutional protections. The second issue concerns the matter of the “legitimising role of crime prevention,” or as von Hirsch (2000, p. 61) posits, “To what extent does crime prevention legitimise impinging on any interests of privacy or anonymity in public space?”

In car parks, there may be little resistance to the installation of CCTV cameras. In part, this is because the public space is utilized for one rather inconsequential purpose – parking vehicles. It is also the case that a car park is a well-defined and clearly marked physical space, meaning that individuals know that it is a car park and can choose to park their vehicle there or not (providing there are other alternatives). These points stand in sharp contrast to how individuals come into contact with CCTV in other public settings.

CCTV in other public settings such as city and town centers, public housing communities, and transportation facilities evokes more resistance on the basis of threats to privacy and other civil liberties, and is associated with a larger number of social harms, including the reinforcement of the notion of a fortress society and the social exclusion of marginalized populations (Clarke 2000). Indeed, it is often these settings that are at the center of the debate over how best to strike a balance between the potential crime reduction benefits and social costs associated with CCTV.

In these other public settings, CCTV may also result in the social exclusion of vulnerable or marginalized populations such as unemployed youths and the homeless. The fear is that, instead of providing assistance for these groups to get off the street so to speak, CCTV, among other interventions like police and security guards, may push them further away from available services and cause increased harm in the form of crime, victimization, or both. Efforts to reduce any social exclusion effect associated with CCTV in these settings would need to involve other services.

Future Directions

Advancing knowledge about the crime prevention benefits of CCTV schemes should begin with attention to the methodological rigor of the evaluation designs. The use of a reasonably comparable control group by all of the 44 included evaluations went some way toward ruling out some of the major threats to internal validity, such as selection, maturation, history, and instrumentation. The effect of CCTV on crime can also be investigated after controlling (e.g., in a regression equation) not only for prior crime but also for other community-level factors that influence crime, such as neighborhood poverty and poor housing. Another possible research design is to match two areas and then to choose one at random to be the experimental area. Of course, several pairs of areas would be better than only one pair.

Also important is attention to methodological problems or to changes in programs that take place during and after implementation. Some of these implementation issues include: statistical conclusion validity (adequacy of statistical analyses); construct validity (fidelity); and statistical power (to detect change). For some of the included evaluations, small numbers of crimes made it difficult to determine whether or not the program had an effect on crime. It is essential to carry out statistical power analyses before embarking on evaluation studies. Few studies attempted to control for regression to the mean, which happens if an intervention is implemented just after an unusually high crime rate period. A long time series of observations is needed to investigate this. The contamination of control areas (i.e., by the CCTV intervention) was another, albeit less common, problem that faced the evaluations.

There is also the need for longer follow-up periods to see how far the effects persist. Of the 44 included schemes, many were in operation for 12 months or less prior to being evaluated. This is a very short time to assess a program’s impact on crime or any other outcome measure, and for these programs the question can be asked: Was the intervention in place long enough to provide an accurate estimate of its observed effects on crime? Ideally, time series designs are needed with a long series of crime rates in experimental and control conditions before and after the introduction of CCTV. In the situational crime prevention literature, brief follow-up periods are the norm, but “it is now recognized that more information is needed about the longer-term effects of situational prevention” (Clarke 2001, p. 29). Ideally, the same time periods should be used in before and after measures of crime.

Research is also needed to help identify the active ingredients of effective CCTV programs and the causal mechanisms linking CCTV to reductions in crime. Forty-three percent (19 out of 44) of the included programs involved interventions in addition to CCTV, and this makes it difficult to isolate the independent effects of the different components, including the unique effect of CCTV, and the interaction effects of CCTV in combination with other measures. Future experiments are needed that attempt to disentangle elements of effective programs. Also, future experiments need to measure the intensity of the CCTV dose and the dose-response relationship, and need to include alternative methods of measuring crime (surveys as well as police records).

In order to investigate displacement of crime and diffusion of crime prevention benefits, the minimum design should involve one experimental area, one adjacent area, and one nonadjacent comparable control area. If crime decreased in the experimental area, increased in the adjacent area, and stayed constant in the control area, this might be evidence of displacement. If crime decreased in the experimental and adjacent areas and stayed constant or increased in the control area, this might be evidence of diffusion of benefits. Unfortunately, few CCTV studies used this minimum design. Instead, most had an adjacent control area and the remainder of the city as another (noncomparable) control area. Because of this, any conclusions about displacement or diffusion effects of CCTV seem premature at this point in time.

This systematic review focused on CCTV’s effects on crime, but it would also be desirable to investigate effects on detection, prosecution, and conviction. Exactly what the optimal circumstances are for effective use of CCTV schemes is not entirely clear at present, and this needs to be established by future evaluation research. But it is important to note that the success of the CCTV schemes in car parks was mostly limited to a reduction in vehicle crimes (the only crime type measured in five of the six schemes) and camera coverage was high for those evaluations that reported on it. In the national British evaluation of the effectiveness of CCTV, Farrington et al. (2007) found that effectiveness was significantly correlated with the degree of coverage of the CCTV cameras, which was greatest in car parks. Furthermore, all six car park schemes included other interventions, such as improved lighting and security guards. It is plausible to suggest that CCTV schemes with high coverage and other interventions and targeted on vehicle crimes are effective. Conversely, the evaluations of CCTV schemes in city and town centers and public housing measured a much larger range of crime types and only a small number of studies involved other interventions. These CCTV schemes, as well as those focused on public transport, did not have a significant effect on crime.

Crime policy is rarely formulated on the basis of hard evidence, and the use of CCTV is no exception. Campbell Collaboration systematic reviews, like the one presented here, provide the most rigorous source for scientific evidence on the leading criminological interventions. It is high time that the evidence is put at center stage in political and policy decisions about preventing crime.

Bibliography:

- Armitage R, Smyth G, Pease K (1999) Burnley CCTV evaluation. In: Painter K, Tilley N (eds) Surveillance of public space: CCTV, street lighting and crime prevention, vol 10, Crime prevention studies. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey

- Clarke RV (2000) Situational prevention, criminology, and social values. In: von Hirsch A, Garland D, Wakefield A (eds) Ethical and social perspectives on situational crime prevention. Hart, Oxford, UK

- Clarke RV (2001) Effective crime prevention: keeping pace with new developments. Forum Crime Soc 1(1):17–33

- Farrington DP, Gill M, Waples SJ, Argomaniz J (2007) The effects of closed-circuit television on crime: metaanalysis of an English national quasi-experimental multi-site evaluation. J Exp Criminol 3:21–38

- Gill M, Spriggs A (2005) Assessing the impact of CCTV, Home Office Research Study No. 292. Home Office, London

- Hier SP (2010) Panoptic dreams: streetscape and video surveillance in Canada. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB (2001) Practical meta-analysis. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Norris C (2007) The intensification and bifurcation of surveillance in British criminal justice policy. Eur J Crim Policy Res 13:139–158

- Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Blumstein A (2007) Key issues in criminal career research: new analyses of the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Savage C (2007) US doles out millions for street cameras: local efforts raise privacy concerns. Boston Globe, 12 Aug 2007. www.boston.com

- Sivarajasingam V, Shepherd JP, Matthews K (2003) Effect of urban closed circuit television on assault injury and violence detection. Inj Prev 9:312–316

- Tilley N (1993) Understanding car parks, crime and CCTV: evaluation lessons from safer cities, Crime prevention unit series paper, No. 42. Home Office, London

- von Hirsch A (2000) The ethics of public television surveillance. In: von Hirsch A, Garland D, Wakefield A (eds) Ethical and social perspectives on situational crime prevention. Hart, Oxford, UK

- Welsh BC, Farrington DP (2009a) Making public places safer: surveillance and crime prevention. Oxford University Press, New York

- Welsh BC, Farrington DP (2009b) Public area CCTV and crime prevention: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Justice Q 26:716–745

- Williamson D, McLafferty S (2000) The effects of CCTV on crime in public housing: an application of GIS and spatial statistics. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology, San Francisco

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.