This sample Co-Offending Research Paper is published foreducational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing yourassignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic ataffordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

This research paper is a general introduction to the subject of co-offending. In-depth treatments of specific topics in co-offending are provided in the articles by Hochstetler (decision-making), van Mastrigt (attributes of co-offenders), and Weerman (theorizing co-offending).

Co-offending is the commission of a crime by more than one person. It is often called “group crime,” although that term is somewhat misleading, as the vast majority of co-offenses are committed by only two offenders (see Size, below). Co-offending is common and has been observed and studied by criminologists for at least a century, since Breckinridge and Abbot (1912) remarked on its high frequency among delinquent boys appearing in the juvenile court of Cook County, Illinois. (Shaw and McKay 1931) also commented on the prevalence of co-offending among boys appearing in the Cook County juvenile court in 1928. The study of co-offending became established in the 1960s, grew slowly through the rest of the twentieth century, and has begun to flourish in the early twenty-first century, partly because of a growing awareness of the applicability of the theories and methods of social network analysis (Carrington 2011).

Co-offending is studied as a phenomenon of interest in itself and also because it can provide insight into other criminological phenomena, such as problems in the measurement of crime, social contagion of criminal attributes and behavior, and criminal networks, gangs, and organized crime.

Prevalence

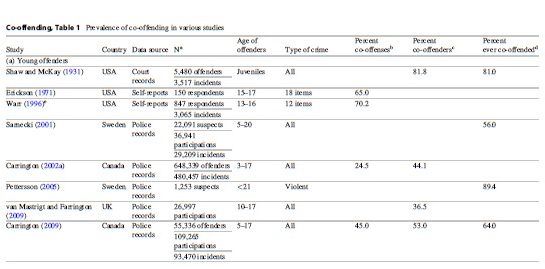

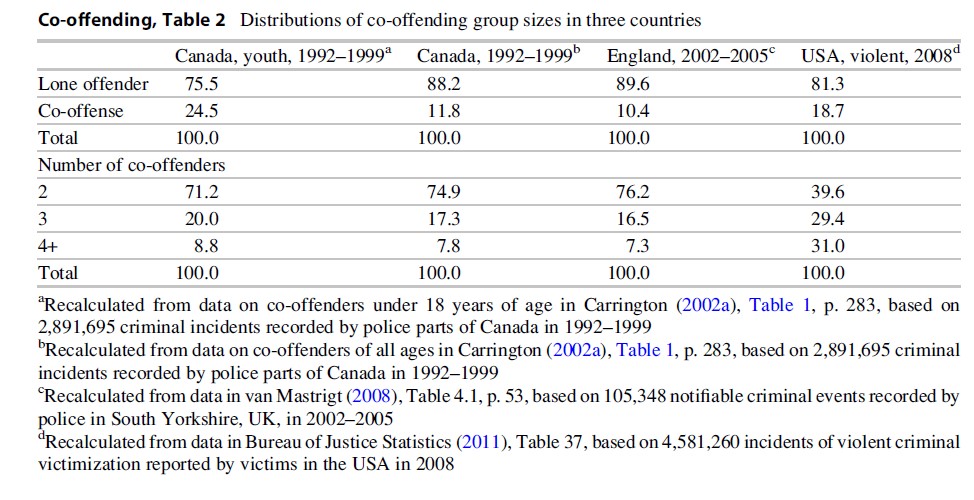

Writers onco-offending are unanimous that it is very common, especially among youngoffenders. However, empirical estimates of its prevalence vary widely – from 10% of criminal incidents to over 80 % of offenders – probably because ofvariations in the definition of prevalence and in the types of data, as well asthe variety of places, times, and samples, that have been used to measure it (Table1). van Mastrigt and Farrington (2009) point out that in estimating prevalence,offenses (that is, criminal incidents) must be distinguished from offenseparticipations, or the participation of one person in one offense. Sinceco-offenses involve multiple offense participations, prevalence estimates basedon counting co-offenses will be lower than estimates based on counting offenseparticipations. In addition, some authors report a third type of prevalence:the percentage of subjects in the sample who ever co-offended during the periodof observation. Each definition of prevalence provides a different perspective onthe same phenomenon. Estimates of prevalence also differ because they arederived from self-reported versus official (recorded) data (or, occasionally,victim reports), because the sample is limited to a certain age range, such as(commonly) young people, or because different types of crime are included(Table 1).

Early estimates of theprevalence of co-offending tended to be relatively high.

Breckinridge and Abbot (1912) commented that lone offending was rare among the delinquent boys that they studied. Shaw and McKay (1931) reported that 82 % of the offense participations of a sample of boys who came before the Cook County juvenile court in 1928 were in co-offenses, and 81 % of the boys had at least one co-offense in their delinquent careers. Erickson (1971) reviewed 11 studies of juvenile delinquency in the United States prior to 1935 and found that the reported prevalence of co-offending ranged between 70 % and 80 % of offenses; his own research on self-reported delinquency found that 65 % of offenses were co-offenses. Of the offenses that were self-reported by a sample of 13–16-year-olds in the National Survey of Youth in 1967, 70 % were co-offenses (Warr 1996).

Estimates based on more recent data are lower. Sarnecki (2001) reports that 56 % of the young offenders registered by the Stockholm police between 1991 and 1995 were involved in at least one co-offense during that period. Fifty-one percent of the recorded offenses committed between the ages of 10 and 32 by the boys in the Cambridge Study were co-offenses (Reiss and Farrington 1991), as were 37 % of recorded offense participations involving young persons in the British police data for 2002–2005 analyzed by van Mastrigt and Farrington (2009) and 25 % of offenses involving young persons in Carrington (2002a) Canadian police data for 1992–1999.

The prevalence of co-offending is much lower in the very few studies that analyze population samples of offenders of all ages. van Mastrigt and Farrington (2009) report that only 10 % of offenses by offenders of all ages were co-offenses; Carrington (2002a) reports 12 %; and Becker and McCorkel (2011) report 18 %.

Co-Offending And The Measurement Of Crime

The phenomenon of co-offending has important implications for the validity of simple crime statistics, whose calculation often implicitly assumes that one incident means one offender, so that the count of criminal incidents equals the count of offenders. Ignoring co-offending can also bias more advanced statistics, such as the effect parameters in regression models of sentencing outcomes (Waring 2002).

The Age-Crime Curve

The well-known age-crime curve is a plot of age-specific crime rates by the year of age of the offenders. Invariably, it relies on counts of offenders, not of incidents – or, more accurately, on counts of offense participations. However, since co-offending is more common among young people, the age-crime curve exaggerates the rate of youth crimes, while accurately depicting the rate of young offenders (Reiss and Farrington 1991; van Mastrigt and Farrington 2009). An age-crime curve that is adjusted for differential age-related rates of co-offending also exhibits the characteristic peak during adolescence, but it is considerable less sharp than the unadjusted age-crime curve (van Mastrigt and Farrington 2009, Fig. 2, p. 565): that is, the elevated rate of co-offending in adolescence accounts partly, but by no means entirely for the characteristic shape of the age-crime curve during adolescence.

Probability Of Conviction

Co-offending also affects the calculation of the probability of conviction, which is used by researchers and policy-makers to assess flow through the criminal justice system and to assess the effectiveness of crime prevention and crime control policies and programs (van Mastrigt and Farrington 2009). Often the probability of conviction is calculated by dividing the number of persons convicted by the number of reported criminal incidents – again, implicitly assuming that one incident means one offender (a further inaccuracy is introduced when incident counts are weighted by the number of victims). Co-offending results in inflated conviction probabilities: for example, if all incidents involved two co-offenders, and all offenders were convicted, the probability of conviction would be calculated as 2.0, instead of the correct figure of 1.0.

The Dark Figures Of Co-Offending

Co-offending also results in inaccurate offender-based crime statistics because of the various ways in which co-offenders are omitted from reported counts of offenders. As with solo offenders, co-offenders may be omitted because the incident was not reported to, or recorded by, police; or because recorded incidents were not cleared, so that the number and attributes of the offender(s) are not known. In addition, in co-offenses that are recorded and cleared, only a subset of the co-offenders may be identified and counted. This results in biases in statistics on group crime, age and crime, possibly gender and crime, and any other aspects of crime that are correlated with co-offending. However, some writers suggest that co-offenses have a higher probability than solo offenses of being reported to police; if true, this would result in further biases in the statistics discussed above (van Mastrigt 2008).

Characteristics Of Co-Offending Groups

Size

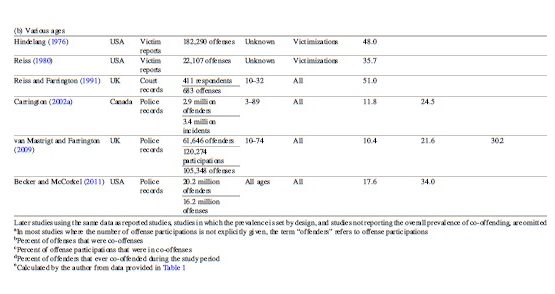

The majority ofco-offenses involve only two co-offenders (Carrington 2002a; Reiss 1988; Reissand Farrington 1991; Shaw and McKay 1931; van Mastrigt 2008). Table 2 summarizes the distributions of co-offending group sizes from recent large-scalestudies in three countries. In police-reported data from England and Canada,for all types of offenses and all ages of offenders, three-quarters of co-offensesinvolved only two co-offenders, and less than 10 % involved more than threeco-offenders. The proportion of multiple-offender groups is much higher in theAmerican data on violent victimizations: more than 30 % of victimizationsinvolved more than three offenders. The discrepancy may be due to the use of a ratherloose definition of “involvement” of co-offenders in a crime by victimsreporting to a victimization survey.

Composition

Co-offending groups have a strong homophilous tendency: that is, co-offenders tend to be similar in age, gender, ethnicity, place of residence, and criminal experience (Pettersson 2005; Reiss 1988; Sarnecki 2001; van Mastrigt and Farrington 2011; Warr 2002; Weerman 2003). This observed similarity lends itself to interpretations in terms of co-offender selection, or a preference for similar people as accomplices (Reiss and Farrington 1991; Warr 2002). On the other hand, the results of stochastic modeling suggest that a not-inconsiderable part of the observed homophily can be accounted for simply by the composition of the pool of potential accomplices. This is particularly the case for the frequent observation that female offenders exhibit lower co-offending homophily than males (Carrington 2002b).

Other processes than homophilous preference or random selection have been invoked to explain the composition of co-offending groups. One explanation, based on rational choice theory, emphasizes a conscious, rational decision-making process in the choice of co-offenders (Tremblay 1993). Other writers, influenced by routine activities theory, propose that offenders encounter potential accomplices in “convergence settings” such as neighborhoods, schools, or other “hangouts.” Thus, offenders become co-offenders through a process of constrained choice.

Stability

Co-offending relationships tend to be short-lived: the majority of co-offending pairs commit only one (recorded) offense together (McGloin et al. 2008; Reiss and Farrington 1991; Sarnecki 2001; van Mastrigt 2008; Warr 1996). However, some professional criminals such as burglars maintain relatively long-term criminal collaborations.

Correlates Of Co-Offending

The main characteristics of crimes and offenders that are associated with the frequency of co-offending are the type of crime and the age of the offender. There is also some evidence of weak relationships between co-offending and the sex or gender, ethnicity or race, and criminal experience of the offender.

Type Of Crime

The strongest predictor of co-offending is the type of crime that is being committed. Some types of crime, such as burglary, robbery, arson, and theft of or from a motor vehicle, are characterized by high rates of co-offending (Carrington 2002a; Reiss and Farrington 1991); and these high rates are not accounted for by confounding factors such as the offender’s age and criminal experience (Carrington 2009; van Mastrigt and Farrington 2009). Other types of crime have characteristically low rates of co-offending, for example, sexual assault and other sex crimes, drug possession, drink-driving, and administrative offenses such as breach of conditions of bail or probation. Generally, offenses committed by co-offenders tend to be more serious than those committed alone (Erickson 1971) – a phenomenon called social amplification. Carrington (2002a) found that group crimes were more likely than solo crimes to involve a weapon, particularly a firearm, and to involve major property damage or loss, or major injury or death. Vandiver (2010) found that co-offending with a boy increased the level of seriousness of sexual offenses committed by girls.

Age Of The Offender

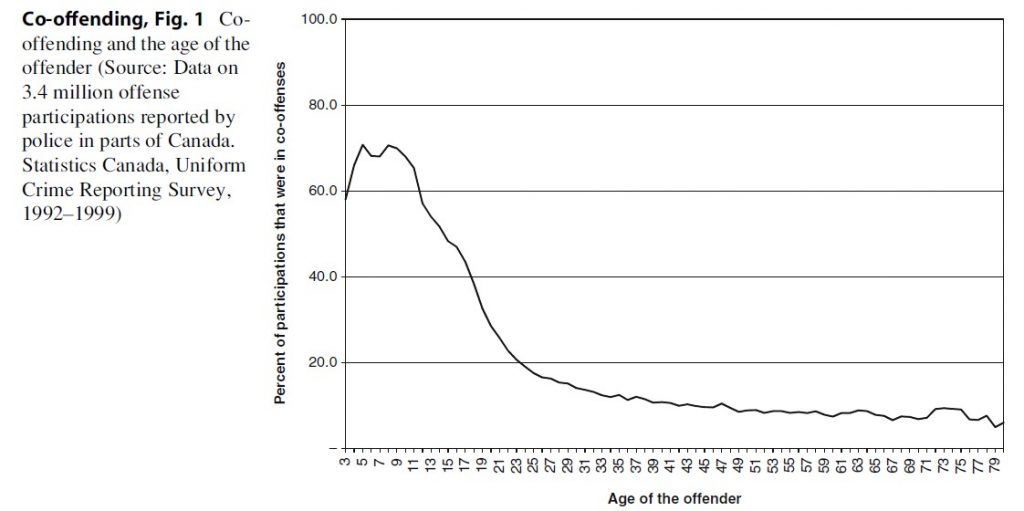

The age of theoffender is by far the strongest offender-related correlate of co-offending. Co-offendingis much more prevalent among young than adult offenders (compare columns 1 and2 of Table 2): the age/co-offending curve rises to a peak in adolescence, and fallsmonotonically with age thereafter (Fig. 1). However, the age/ co-offendingcurve varies by type of crime and the offender’s criminal career (Carrington2002a, 2009; van Mastrigt and Farrington 2009).

The Offender’s Criminal Experience

Co-offending is most common at the onset of the criminal career and decreases with criminal experience (Reiss and Farrington 1991), except among child offenders under 12 years of age (Carrington 2009). This pattern is not accounted for by the decrease with age in co-offending, although age and experience are correlated. However, more active (“high-rate”) offenders are more likely to co-offend than low-rate offenders, and this tendency masks the decline in co-offending in their careers (Carrington 2009).

Gender And Ethnicity Of The Offender

The probability of co-offending has also been found to be weakly related to the offender’s gender or sex, with female offenders being slightly more likely to co-offend. There is also a small body of evidence suggesting a relationship between co-offending and the offender’s ethnicity or race.

Social Contagion

Higher rates of co-offending observed at the onset of the criminal career and the sustained co-offending exhibited by some persistent offenders (Reiss 1988; Carrington 2009) suggest that co-offending may be a mechanism through which criminal attitudes and behavior are transmitted to criminal neophytes by more experienced and influential accomplices. This process has variously been conceptualized as tutelage, recruitment (Reiss 1988; van Mastrigt and Farrington 2011), instigation (Warr 1996), social learning, peer influence (Warr 2002), and mentorship (Morselli 2009). A variant account of social contagion is the idea that co-offending with more experienced criminals provides neophytes with criminal opportunities – access to criminal capital in the form of expertise and networks – just as collaboration with more experienced and established practitioners does in other occupations (Becker and McCorkel 2011).

The ability of more experienced and committed criminals to influence impressionable neophytes is often attributed to a difference in age, but has also been attributed to gender roles in the case of female offenders who are hypothesized to have been influenced or coerced into co-offending with their male romantic partners, particularly in cases of child sexual abuse.

Co-Offending Networks

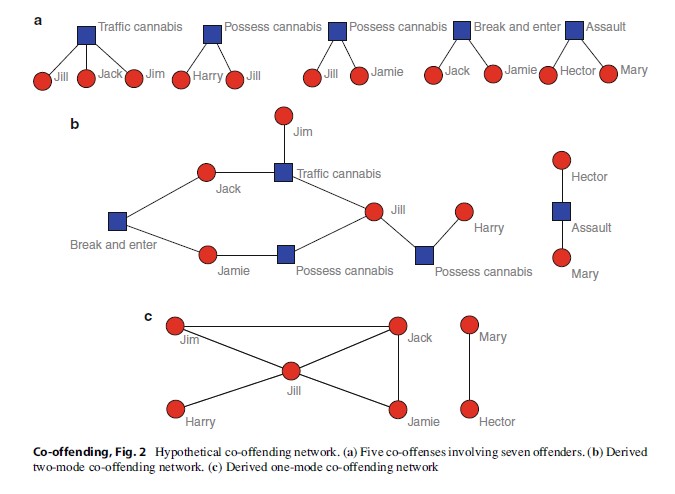

Co-offending data havebeen used to study the structure and dynamics of gangs, criminal or delinquentgroups, organized crime groups, and criminal markets. Linking co-offensestogether by the offenders that they have in common results in a co-offendingnetwork, which is one type of criminal network. In the hypothetical exampleshown in Fig. 2, there are five co-offenses involving seven offenders, some ofwhom such as Jill are repeat offenders (Fig. 2a). Linking together incidentsconnected by common offenders such as Jill results in a bipartite, or two-modenetwork (Fig. 2b), so-called because the nodes, or vertices, are classifiedinto two mutually exclusive classes (offenders and incidents), and the lines,or edges, exist only the classes. This type of network is also known as anaffiliation network, because it represents individuals’ affiliations – in thiscase, to criminal events. A two-mode or affiliation network can be analyzed asit is, but criminal network researchers usually work with the simpler one-modeperson-to-person network shown in Fig. 2c, which can be derived from thetwo-mode network by a simple operation of matrix algebra. Real-lifeco-offending networks may have hundreds or even thousands of nodes (e.g.,Sarnecki 2001).

The theories and techniques of social network analysis are used to analyze these networks in order to identify static and dynamic structures and test hypotheses about them (Carrington 2011). Whether such networks are, or contain, gangs or organized crime groups is a matter of conceptual definition and empirical investigation. Research in this area has identified various structural features of co-offending networks and interpreted them in terms of issues in the study of gangs and organized crime.

In this extension of co-offending research, the phenomenon of co-offending is of interest not in itself, but as evidence of connections among offenders (Fig. 2c), which may be used instead of, or in addition to, other evidence derived from wiretaps, surveillance, interviews, etc., to study the social organization of crime and criminals. Co-offending data have played only a very limited role in the study of gangs and organized crime. Co-offending per se constitutes only one kind of connection among criminals, and only a small part of the activities of organized criminals and enterprises; consequently, co-offending networks provide only a skeletal, incomplete, and potentially biased view of underlying criminal networks. Most network-oriented research on organized crime and criminal markets has relied on data other than co-offending, such as self-reports, police wiretaps and other intelligence, and reports of police investigations (see, e.g., the reviews in Carrington 2011; Morselli 2009). Some researchers have compared the value of co-offending data to that of other sources of data on organized crime (Malm et al. 2010).

Gangs As Cohesive Subgroups

One approach to the question of the existence and structure of so-called gangs in co-offending networks is to identify cohesive subgroups within the network. A cohesive subgroup is a set of nodes that are connected together with relatively dense ties. In Fig. 2c, Mary and Hector form one cohesive subgroup, and the other offenders form a second. Within the second subgroup, there are two smaller subgroups whose members are all directly interconnected (termed “cliques”): Jill, Jamie and Jack, and Jill, Jim and Jack. These four offenders could be seen as the core, with Harry being somewhat peripheral. Research on real-life co-offending networks has generally found that they consist of many small groups of less than a dozen members that are loosely linked together by relatively sparse connections into much larger networks (McGloin 2005; Reiss 1988; Sarnecki 2001; Warr 1996).

Criminal Performance

A central question in the study of organized crime and criminal markets is that of criminal performance, or achievement: what factors affect the likelihood and degree of success of individuals and groups in their criminal activities? The study of criminal networks has adapted ideas from the wider literature on networks and success in legitimate business, notably Ronald Burt’s theory of structural holes and brokerage, and Nan Lin’s network theory of social capital.

Nonredundancy, Structural Holes, And Brokerage

The sparse connections between cohesive subgroups in co-offending networks create nonredundancy in some individuals’ own ego-networks: that is, co-offending is rare among the focal individual’s co-offenders. Opportunities for criminal brokerage arise or are created when an individual forms a unique bridge between otherwise unconnected groups that possess reciprocally valued resources. In the subgroup of five co-offenders in Fig. 2c, one of Jill’s co-offenders, namely, Harry, does not co-offend with anyone else. This makes Jill’s connection with Harry nonredundant, or necessary, for the cohesiveness of the subgroup, and makes Jill a structurally important member of the group. To put it differently, before Jill co-offended with Harry, there was a structural hole, or disconnect, between Harry and the others, which his co-offense with Jill bridged. By bridging this structural hole, Jill became a broker, or liaison, between Harry and the other three members of the subgroup, and may benefit from this structural advantage. There remains a structural hole between Mary and Hector and the other five offenders, and if one of the five co-offended with Mary or Hector, he or she would become a broker between the two formerly disconnected subgroups, and structural advantage would accrue to him or her.

Morselli (2009) and his colleagues and Malm and her colleagues (Malm and Bichler 2011; Malm et al. 2010) have explored the antecedents and consequences of criminal brokerage based on individuals’ positions in criminal groups and networks, and in criminal transaction networks, although co-offending is only a small part of the data on organized crime networks that they analyze.

Embeddedness And Criminal Capital

The concept of criminal capital is adapted from that of social capital, which refers to the resources that are available as a result of one’s connections to others. By extension, criminal capital refers to the knowledge, skills and other resources that are derived from embeddedness in criminal networks. The value of criminal capital both for individuals and for criminal groups has been demonstrated with data on co-offending networks (McCarthy and Hagan 1995; Waring 2002).

Centrality has been used as an indicator of an individual’s embeddedness in a criminal group. Individuals who occupy central positions in co-offending groups or networks tend to be more experienced and prolific offenders (Sarnecki 2001), to have the most pro-criminal attitudes, and to have the highest risk of violent victimization. Boys tend to be more central than girls.

Interdiction

At least since the publication of Harper and Harris’s (1975) paper on link analysis, researchers and practitioners have appreciated that knowledge of connections among criminals, including co-offending networks, can be useful in identifying criminal groups and their membership, and in understanding their organizational structure and dynamics in order to disrupt or destroy them. McGloin’s (2005) research has shown the potential effectiveness of identifying, targeting, and removing or neutralizing “key players,” who are individuals who occupy key positions in the criminal network, as central members or as “cut points,” whose removal would cause disconnection of the network. For example, in Fig. 2c, Jill is both a central figure and a cut point, although the high degree of connectedness among Jill, Jack, Jim and Jamie means that removal of Jill might have only limited success in disrupting the network, by isolating Harry. On the other hand, research by Morselli (2009) and his colleagues calls this strategy into question by research showing the flexibility and adaptability of criminal networks; the implication is that these networks can reconfigure themselves to recover from key player attacks. Malm and Bichler (2011) show that different strategies are implied by the different structures found at different parts of illicit supply chains.

Bibliography:

- Becker S, McCorkel JA (2011) The gender of criminal opportunity: the impact of male co-offenders on women’s crime. Fem Criminol 6:79–110

- Breckinridge SP, Abbot E (1912) The delinquent child and the home. Charities Publication Committee, New York

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (2011) Criminal victimization in the United States, 2008. Statistical Tables. National Crime Victimization Survey. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/ index.cfm?ty¼dcdetail&iid¼245. Accessed 5 Nov 2001

- Carrington PJ (2002a) Group crime in Canada. Can J Criminol 44:277–315

- Carrington PJ (2002b) Sex homogeneity in co-offending groups. In: Hagberg J (ed) Contributions to social network analysis, information theory and other topics in statistics. Stockholm University Press, Stockholm, pp 101–116

- Carrington PJ (2009) Co-offending and the development of the delinquent career. Criminology 47:1295–1329

- Carrington PJ (2011) Crime and social network analysis. In: Scott J, Carrington PJ (eds) SAGE Handbook of social network analysis. Sage, London, pp 236–255

- Erickson ML (1971) The group context of delinquent behavior. Social Problems 19:114–129

- Harper WR, Harris DH (1975) The application of link analysis to police intelligence. Human Factors 17:157–164

- Hindelang MJ (1976) Criminal victimization in eight American cities. Ballinger, Cambridge

- Malm A, Bichler G (2011) Networks of collaborating criminals: assessing the structural vulnerability of drug markets. J Res Crime Delinq 48:271–297

- Malm A, Bichler G, Van De Walle S (2010) Comparing the ties that bind criminal networks: is blood thicker than water? Secur J 23:52–74

- McCarthy B, Hagan J (1995) Getting into street crime: the structure and process of criminal embeddedness. Soc Sci Res 24:63–95

- McGloin JM (2005) Policy and intervention considerations of a network analysis of street gangs. Criminol Public Policy 4:607–636

- McGloin JM, Sullivan CJ, Piquero A, Bacon S (2008) Investigating the stability of co-offending and cooffenders among a sample of youthful offenders. Criminology 46:155–188

- Morselli C (2009) Inside criminal networks. Springer, New York

- Pettersson T (2005) Gendering delinquent networks.

- A gendered analysis of violent crimes and the structure of boys’ and girls’ co-offending networks. Young Nord J Youth Res 13:247–267

- Reiss AJ (1980) Understanding changes in crime rates. In: Feinberg SE, Reiss AJ (eds) Indicators of crime and criminal justice: quantitative studies. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

- Reiss AJ (1988) Co-offending and criminal careers. Crime Justice 10:117–170

- Reiss AJ, Farrington DP (1991) Advancing knowledge about co-offending – results from a prospective longitudinal survey of London males. J Crim Law Criminol 82:360–395

- Sarnecki J (2001) Delinquent networks: youth cooffending in Stockholm. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Shaw CR, McKay HD (1931) Social factors in juvenile delinquency, vol II, Report on the causes of crime. National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement, Washington, DC

- Tremblay P (1993) Searching for suitable co-offenders. In: Clarke RV, Felson M (eds) Routine activity and rational choice, vol 5, Advances in criminological theory. Transaction, New Brunswick, pp 17–36

- van Mastrigt SB (2008) Co-offending. Relationships with age, gender, and crime type. PhD dissertation, Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge

- van Mastrigt SB, Farrington DP (2009) Co-offending, age, gender and crime type: implications for criminal justice policy. Br J Criminol 49:552–573

- van Mastrigt SB, Farrington DP (2011) Prevalence and characteristics of co-offending recruiters. Justice Q 28:325–359

- Vandiver DM (2010) Assessing gender differences and co-offending patterns of a predominantly “male-oriented” crime: a comparison of a cross-national sample of juvenile boys and girls arrested for a sexual offense. Violence Victims 25:243–264

- Waring EJ (2002) Co-offending as a network form of social organization. In: Waring EJ, Weisburd D (eds) Crime and social organization, vol 10, Advances in criminological theory. Transaction, New Brunswick, pp 31–47

- Warr M (1996) Organization and instigation in delinquent groups. Criminology 34:11–37

- Warr M (2002) Companions in crime: the social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Weerman FM (2003) Co-offending as social exchange: explaining characteristics of co-offending. Br J Criminol 43:398–416

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.