This sample Community Service in Europe Research Paper is published foreducational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing yourassignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic ataffordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Community service orders have been introduced in England and Wales 1972 and since then have become one of the most important community sanctions in many European countries and outside Europe. Community service has gained importance, in particular, for offenders who are not able to pay a fine, but also to replace short-term imprisonment. It has an essential role as the principal community sanction in Spain, Hungary, England and Wales, Scotland, Latvia, and all Nordic countries. The scope of application varies considerably when looking at the range of hours that can be imposed. In Europe, one regularly finds a scope between 40 and 240 h, in the USA, between 100 and 500 h. Empirical studies have shown that the implementation of community service has been successful. In this regard, it is important that most offenders assigned to community service programs are completing their working hours. The available evidence suggests that community service is (at least) a promising alternative in terms of reducing recidivism. Several results point to significant differences between offenders who are sentenced to imprisonment and offenders who participate in community service. Recent meta-analyses demonstrate a stronger effect size (.07) than earlier ones, which may be explained by the better structured programs considering “what-works” criteria. The authors advocate to extend community service and to ensure that it comes to replace imprisonment (instead of replacing other noncustodial sanctions).

Historical Development

Historically forced labor has a long tradition in human history. In penal history, it was one of the core elements of prison life. Forced prison labor is still widely accepted and exempted from the ban on forced labor as expressed in international human rights standards. First efforts to ban forced labor date back to 1930 when the International Labour Organisation (ILO) initiated the Convention No. 29 and in 1957 a second one (Convention No. 105) after ILO had been linked to the UN in 1946. Both Conventions aimed at fighting against slavery and any other form of involuntary (forced) labor (see de Jonge 1999, pp. 321 ff.). The ban on forced labor can also be found in art. 8 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and in art. 4 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR). Art. 8(3) (c) of the ICCPR, however, allows for forced or compulsory labor “normally required of a person who is under detention in consequence of a lawful order of a court, or of a person during conditional release from such detention.” The ECHR in the same wordings allows for forced labor only during detention and on conditional release. Strange enough to permit forced labor during the post-release stage, both Conventions do not clearly differentiate between remand and sentenced prisoners. Theoretically, one could think of forced labor in remand custody, but as a consequence of the presumption of innocence (see art. 6 ECHR), it is a common opinion and jurisprudence to exclude remand prisoners from compulsory work. The ILO Convention No. 29 had allowed forced labor only for sentenced prisoners, not for remand prisoners or those conditionally released (see de Jonge 1999, p. 327). The German Constitution as many other national laws allows forced labor only for sentenced prisoners (see art. 12(3) Federal Constitution, Grundgesetz).

Therefore, from an international human rights view, it might be difficult to justify community service as an independent sanction as far as it is not strictly bound to replace a prison sentence. In that case, it can be justified with the argument a maiore ad minus that forced labor in the community is a less intrusive sanction than imprisonment plus forced labor. If, however, community work does not replace a prison sentence, but other alternatives such as fines or conditional discharge without intervention, it can be questioned as being a violation of the ban on forced labor.

The German Constitutional Court has found a way out of this dilemma by going back to the roots of the ban of forced labor in the German Constitution after World War II: The constitutional ban was implemented as a fundamental human right with regard to forced labor in the preceding Nazi-era, where thousands of people were killed by hard labor in concentration camps and elsewhere. The legislator wanted to outlaw such inhuman hard labor, which in no way is comparable with some few hours of labor, in particular if its purpose is the rehabilitation (resocialization, education) of the offender (see Bundesverfassungsgerichtsentscheidungen, BVerfGE 74, pp. 102 ff., 122 ff.).

Germany did not introduce community service as an independent sanction in the Criminal Law for adults of at least 21 years of age, but only as a substitute sanction to prevent imprisonment for fine-defaulters (1983). This is different in the field of juvenile justice where the German Juvenile Justice Act (JGG) provides for community service as an independent sanction as well as a condition of diversion or of a suspended sentence (see Dunkel 2011a). The practice extensively uses community service: 44 % of all sentenced juvenile and young adult offenders (aged 14–21) in 2010 received a community service order (see D€unkel 2011a; Heinz 2012).

First community service programs were introduced in the USA with female traffic offenders in Alameda County, California, in 1966, with local initiatives following in several counties throughout the USA (Wright 1991, p. 40). The aim of different initiatives was to create community service programs as a viable alternative to incarceration (van Ness 1986, p. 194).

Community service as an alternative to prison in Europe first has been introduced in 1972 in England and Wales. Other European countries followed in the 1980s: Italy 1981, Denmark and Portugal 1982, France 1983, the Netherlands 1985 (see Albrecht and Sch€adler 1986).

With the exception of Denmark, the Scandinavian countries introduced community service only in the 1990s. Denmark started an experiment with community service – as mentioned – already in 1982. However, the sanction was not introduced in a wider scale in the Nordic sanctions systems until the 1990s. Community service appears in different forms. Finland and Norway treat community service as an independent sanction (although Norway renamed “community service” in 2001 as “community punishment”). In Denmark and Sweden, community service is attached either to conditional imprisonment or a probation order. In Finland, long (over 1 year) conditional prison sentences may be combined with a short (20–60 h) community service order. In Denmark, community service can be combined also with fines and unconditional imprisonment. In addition, community service may be attached with separate conditions concerning residence, school attendance, or work. Also Norway allows specific conditions regarding the offender’s dwelling, work, and treatment. The maximum number of community service hours varies from 200 (Finland) to 420 (Norway). The range of community service in Denmark was from 30 to 240 h, but the maximum was raised to 300 h in 2012.

Countries differ also in the sense, how strictly community service has been defined as an alternative to imprisonment, and not to other sanctions. Finland has followed the strictest policy in this respect, by adopting a specific two-step procedure. First, the court is supposed to make its sentencing decision by applying the normal principles and criteria of sentencing without considering the possibility of community service. Second, if the result of this deliberation is unconditional imprisonment (and certain requirements are fulfilled), the court may transform the sentence into community service. In principle, community service may therefore be used only in cases in which the accused would otherwise have received a sentence to unconditional imprisonment. Other countries are less strict in this point. In connection of the 2001 reform in Norway, the scope of community punishment was extended to be used, not only instead of imprisonment, but as a replacement penalty for juvenile offenders who had previously been sentenced to supervised conditional imprisonment. In Iceland, the decision over community service is taken by the prison administration, not the courts. This avoids effectively the risks of net-widening (but could raise questions from constitutional point of view in some other countries).

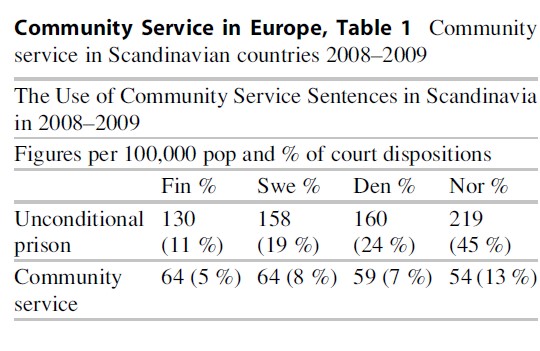

In the turn of the2000s, several Scandinavian countries completed law reforms in order toincrease the use of community service. Sweden created a combination ofcommunity service and suspended sentence, thus increasing the number of annualcases from 2,000 to around 4,000. Denmark changed its policy in 2000 byallowing community service to be used also for drunken driving (which was previouslyforbidden). Within a period of two years, this increased the number ofsentences from 1,000 to 4,000. Norway, in turn, tried to increase thecredibility of community service by changing the title to community punishmentby including also other elements in the sentence and by expanding the scope ofapplication also to drunken driving. This resulted in an increase from around500 cases to the present little over 2,500 cases (Table 1).

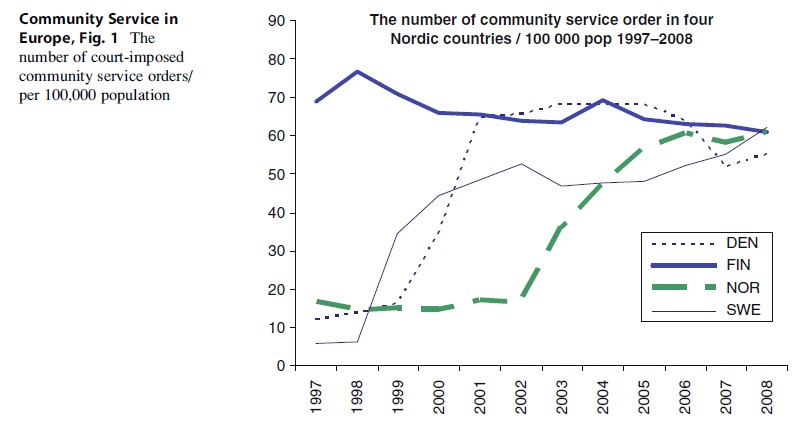

Relative to population community service is used roughly on a same scale in all countries, with Finland and Sweden on the lead (64) and Denmark and Norway following (59 and 54). A longer trend from 1997 onwards shows that three out of four countries expanded the use of community service in the shift of the millennium, while Finland had used this alternative more extensively already from the mid-1990s (Fig. 1).

Non-European countries have introduced community service as well, in particular in the Anglo-Saxon world (Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and USA), but also in South America, recently, community service is developed as an alternative sanction. In these countries (as in Europe already earlier), juvenile criminal law is a forerunner for reforms of the sanctions system (all juvenile justice jurisdictions dispose of community service orders, see Tiffer-Sotomayor 2000).

Legal Conditions And Basic Philosophies Of Community Service

Community service involves the performance of unpaid work, during leisure-time and within a given period, for the good of the community. The offender “shall pay back to the community via unpaid work” (Goldson 2008, p. 78; D€unkel et al. 2011, p. 1673). Thus, the original philosophy of community service fits very well with the special preventive aim of punishment (resocialization or with regard to juvenile justice: education) as well as to the idea of restorative justice. In the context of restorative justice, another orientation is outlined by Wright (1991, p. 44): “The emphasis of community service is not on punishment nor on rehabilitation; rather, it is on accountability.” It focuses “not on offenders’ needs but their strengths; not on their lack of insight but their capacity for responsibility; not on their vulnerability to social and psychological factors but their capacity to choose. These differentiate a rehabilitative response from a restorative/community service response to crime. And punitive elements of community service orders may attend its imposition, within a restorative system, only as by-products of the offender’s commitment of time and effort” (Wright 1991, p. 44).

However, in the last 20 years, some countries have redefined community service and also renamed it as “punishment in the community” or “community punishment” and thus emphasizing the repressive goal of retribution. This was particularly the case in England and Wales (1998), but also in Norway (2001). Therefore, the nature and content of community service may be rather different from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

The status and contents of community service may vary. It may:

• be imposed as an independent sanction or as an adjunct to another sanction

• replace only prison sentences or also other penalties

Although community service is widely accepted in the field of juvenile justice, some countries explicitly exclude the very young age groups, e.g., under 16 (England and Wales) or 15 (South Africa).

The range of hours (and implicitly the range of prison sentences that can be replaced) varies considerably:

In Europe, the range mostly is from 40 to 240 h, often with a maximum of 120 h for juvenile offenders. Even in countries with normally great similarities in their penal policy such as the Scandinavian countries, large variations can be seen: In Finland, the maximum is 200; in Denmark, 300; in Norway, 420 h.

In South Africa, the range is from 50 to 240 h (to be completed in 1 year).

In New Zealand, the range with 40–400 h is considerably wider. Up to 200 h should be computed in one year, more than 200 h in two years. If offenders do not meet the requirements of the sentence, up to three months of imprisonment or a fine of up to 1,000 $ (NZ) can be imposed (see http://www.corrections.govt.nz/communityassistance/corrections-in-the-community/communitywork.html).

In the USA, the range is regularly between 100 and 500 h (to be computed in one year).

International Human Rights Standards Concerning The Imposition And Execution Of Community Service

Human rights aspects are of major importance in the decision-making process as the principle of proportionality (Verha€ltnisma€ßigkeitsgrundsatz), derived from the principle of Rechtsstaat (rule of law, art. 20(3) of the Constitution), is to be considered for the imposition of community service, i.e., the number of working hours imposed must be related to the seriousness of the offense. In most countries, therefore, the maximum number of hours is fixed by law. In Germany, where community service as an independent sanction is available only in juvenile justice, no maximum is fixed by law. Therefore, the principle of proportionality is of special importance to avoid unjustified high number of several 100 h.

The Recommendation of the Council of Europe concerning Community Sanctions or Measures (CSM) of 1992 (Rec. (92)16) stipulates that “the nature, content and methods of implementation … shall not jeopardise the privacy or the dignity of the offenders or their families, nor lead to their harassment. … Safeguards shall be adopted to protect the offender from insult and improper curiosity or publicity” (Rule 23).

The European Rules for Juvenile Offenders Subject to Sanctions or Measures (ERJOSSM) of 2008 (Rec. (2008)11) – as earlier Recommendations of the Council of Europe and the UN – assess that “sanctions or measures shall not humiliate or degrade the juveniles subject to them” (Rule 7). And: “Sanctions or measures shall not be implemented in a manner that aggravates their afflictive character or poses an undue risk of physical or mental harm” (Rule 8). In the commentary to these rules, reference is made to some forms of community work that can stigmatize offenders such as wearing special uniforms which identify them as offenders and which would not be consistent with the rules (Council of Europe 2009, p. 37). The practice of wearing orange uniforms as it is the case in England and Wales as well as in the Netherlands (and in the USA or South Africa) therefore is a violation of these human rights standards. From a European point of view, totally violating basic human rights standards has been the practice in some US states (and still is in Arizona) to make offenders work in so-called chain gangs, i.e., stigmatizing them by working in a kind of medieval outfit tethered together.

Two more human rights issues have to be mentioned in this context: Rule 37 of the ERJOSSM states that the costs of implementation shall not be borne by the juveniles or their families. And community work shall not be undertaken for the sole purpose of making a profit (Rule 45 ERJOSSM). Therefore, the demand of the South Australian Corrections Service to make the communities pay 200 $ per a day of community service with good reasons has been rejected by the local authorities (see http://www.abc.net. au/news/2012-04-05/community-service-chargecouncil/3934500).

Statistical Developments: Europe And Scandinavia

The use of community service as compared to other community sanctions and measures and imprisonment can be examined most effectively on the basis of enforcement statistics. The Council of Europe’s penal statistics Space I (survey year 2009) and Space II (survey year 2010) provide information both on stock rates and flow rates (/100,000 population) in Europe.

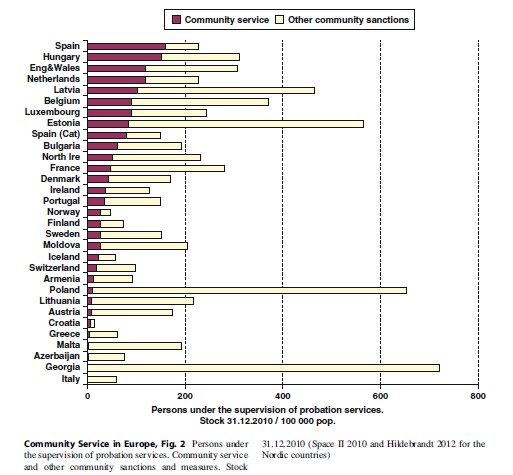

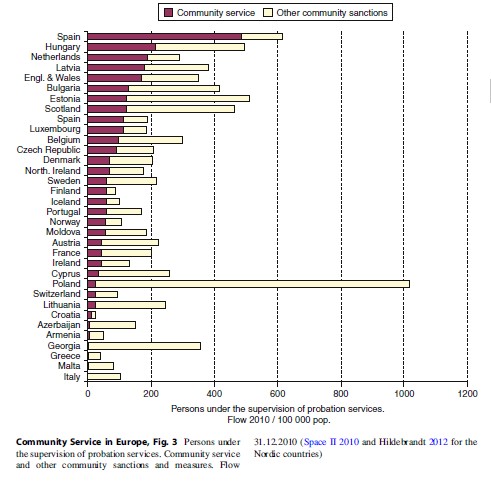

Figure 2 displays thenumber of persons serving community service or other community sanctions underthe supervision of probation services at a given day (31.12.2010). Figure 3 displays the same information on the base of flow statistics.

Community service hasa noteworthy role in over 20 European nations with data in the Council ofEurope’s Space II survey. It has an essential role as the principal communitysanction in Spain, Hungary, England and Wales, Scotland, Latvia, and all Nordiccountries.

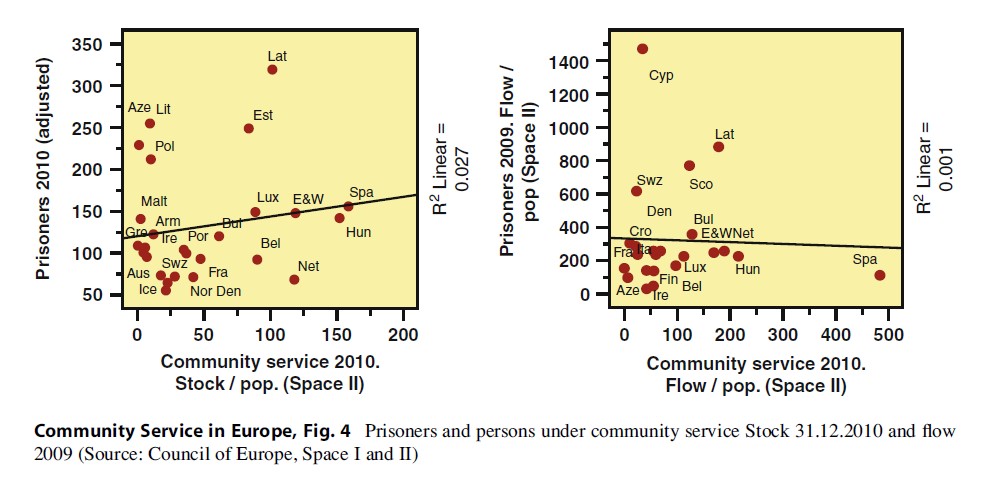

Many of the countrieswith high rates of community sanctions are also countries with relative highincarceration rates (see Dunkel/LappiSeppala/Morgenstern/van Zyl Smit 2010,1058 ff). Figure 4 compares the use of community service and imprisonment onthe base of enforcement statistics.

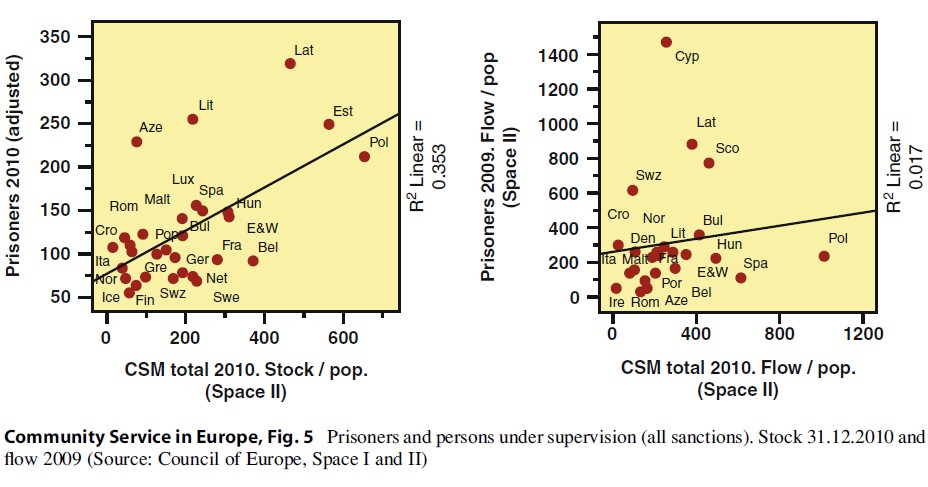

Stock- andflow-statistics give the same result. There is no correlation between thenumber of people in community service and in prison at any given day (stock).Neither is there a correlation between the number of people starting communityservice or entering in prisons during the year (flow). The latter finding is,however, heavily influenced by one outlier (Spain). Should this observation be excluded,one would find a weakly positive correlation. In other words, countries thatuse extensively community service use also imprisonment more. This finding isconfirmed by a comparison between all community sanctions and measures andimprisonment (below) (Fig. 5).

It seems that, in general, the use of imprisonment is not compensated by community sanctions. Countries with high incarceration rates are often (but not always) countries with high community sanctions rates. And countries with low incarceration rates seem to manage also with lower rates of community sanctions. However, one needs to take into account that this comparison includes only community sanctions with supervision under the probation service. It excludes formal types of sanctions such as suspended and conditional sentences without supervision, as well as fines. Should these measures be taken into account, low incarceration countries like the Nordic countries and Germany would rank high in the scale of noncustodial sanctions, but low in incarceration.

Evaluation Research: Recidivism And Reintegration Into Society

Completion Of Community Service Orders, Implementation Of Programs, Etc.

Community service in most countries is organized by the probation service and/or private nonprofit organizations of offender rehabilitation. One major problem in implementing community service is to organize working places and to allocate offenders to adequate working facilities. In particular, in large rural countries or local municipalities, it is sometimes difficult to find working possibilities close to the offender’s residence. As community work has to be unpaid, the kind of work should be of a nature not to compete with regular paid work in the first labor market. Therefore, trade unions are keen to restrict community service to extra work which cannot be provided by normal enterprises.

Empirical studies have shown that the implementation of community service has been successful in many countries (see above) and today is the most important alternative sanction apart from fines and suspended sentences (probation). In this regard, it is important that most offenders assigned to community service programs are completing their working hours. Only a small minority fails. Factors for noncompliance or failure to complete the sentence are a too high number of hours imposed and/or personal problems of the offender to get to work (problems with alcohol and/or drugs, personality problems, unstableness, lack of practical experience with work, refusal to work etc.). The experience of the probation services shows that offenders in these programs often show multiple problems of reintegration which demonstrates the necessity of further rehabilitative measures compared to the sole allocation to a working facility.

One remarkable program in Germany should be mentioned. In Germany, community service is provided only for fine-defaulters as a substitute to imprisonment for nonpayment of a fine (Norway has in 2012 introduced a similar type of sanction (“Botetjeneste”) and also Finland currently is considering one). The German programs go back to the year 1983, but until the mid-1990s, most federal states ran those programs on a rather limited scale. The federal state of MecklenburgWestern Pomerania had a specific problem as 22 % of prisoners in adult prisons were fine defaulters. Therefore, in 1998, a state-wide project was founded that systematically created working facilities and in particular a system of contracting offenders who did not pay and react to the imposition of fine-default imprisonment. The restructuring of probation and private offender rehabilitation services resulted in a structure of systematic allocation to 1,600 working facilities all over the large federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. One special element of the project was to deliver social work and care for specifically difficult offenders who otherwise would not have completed community work. About 70 facilities have established such intensive care programs for fine-defaulters. Another pillar of the project was that fine defaulters, even after they had been sent to prison, were allocated to community service programs and therefore often were released after a few days. The results during the 3-year pilot project starting in 1998 were remarkable: Daily numbers of fine-defaulters decreased from around 120–100 to 50–70, i.e., were reduced by half (see Dunkel and Scheel 2006). The results were so convincing that the Ministry of Justice decided to permanently appoint six social workers who are occupied with electing and allocating offenders to working facilities. The project has achieved a sustained success (the last numbers are from 2010), keeping fine-defaulters in prison almost at a low level achieved in 2001. The placement in community service facilities was in about 75 % of the cases successful, i.e., the offender completed at least partly community service and thus the state saved money by avoiding imprisonment. In total, the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in 2010 saved about 1.6 million €, whereas the cost for the project (mainly the six social workers mentioned above) is about 450,000 € per year. Thus, the cost-benefit is more than one million € per year (see Dunkel 2011b).

Replacing Imprisonment Or Net-Widening? The Example Of Scandinavian Countries

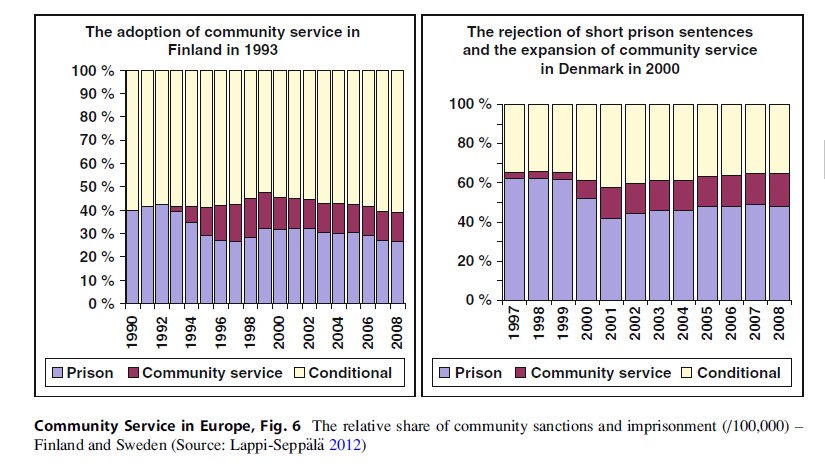

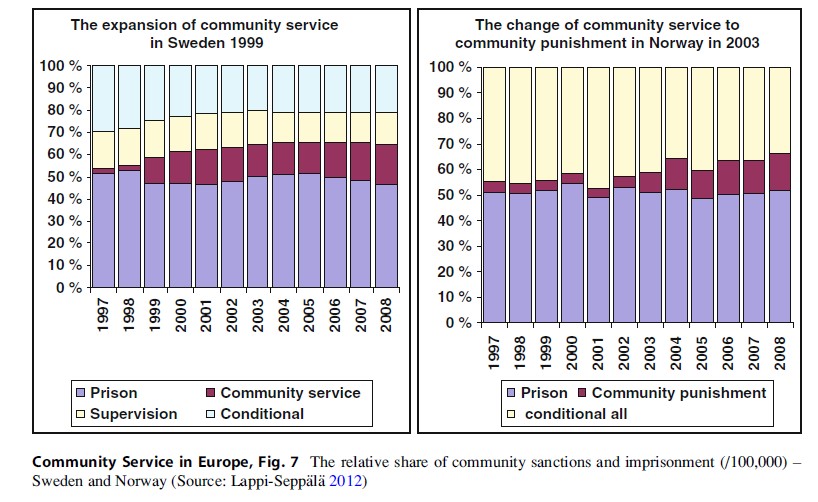

All Nordic countriesadopted or increased the application of community service in the 1990s and early2000s. The following diagrams illustrate how these changes in the sanctionstructures were reflected in the application of other community sanctions andimprisonment in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden (see in more detail Lappi-Seppala 2008) (Figs. 6, 7).

In Finland, communityservice came to replace prison sentences in 1993 without any notablenet-widening. In Denmark, the extension of community service coincided with thereform that abolished the short-term (1–2 weeks) prison sentences. As itappears, the community service came to replace part of these prison sentences.But it also seems that part of previous short-term prison sentences wasreplaced also by conditional sentences (Figs. 6, 7).

In Sweden, the expansion of community service in the year 2000 has replaced both conditional sentences and prison sentences. In 2002 Norway changed the name of “community service” to “community punishment” in order to enhance the credibility of the sanction. This increased the use of the sanction. However, this increase does not seem to be reflected in the share of prison sentences, but rather in the decline in the use of conditional imprisonment.

It looks like four out of five Nordic countries (Iceland included) have been successful in replacing prison sentences by community service. This success is associated with legislator’s aims and intentions. In Finland, it was clearly stated that community service should be used only in cases where the accused would otherwise have received an unconditional sentence of imprisonment. This was ensured with specific legislative arrangements. Results were also seen in the statistics. Along with the increase in the number of community service orders from zero to 3,500, the number of unconditional sentences of imprisonment decreased by a little over 3,000. In Finland, annually some 3,500 community service orders are imposed by the courts. This represents around 35–40 % of the sentences of imprisonment which could have been converted (sentences of imprisonment of at most 8 months). This corresponds to some 400–500 prisoners (10–15 % of the prison population) of the daily prison population.

Assessing Reoffending Effects And Other Benefits

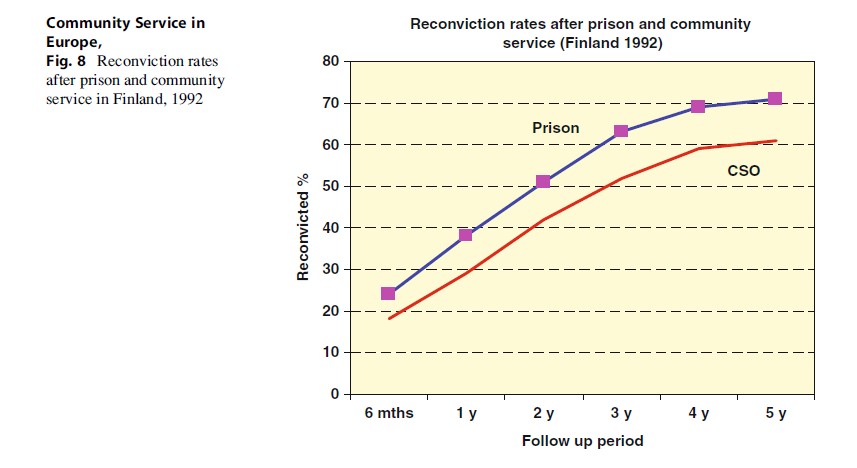

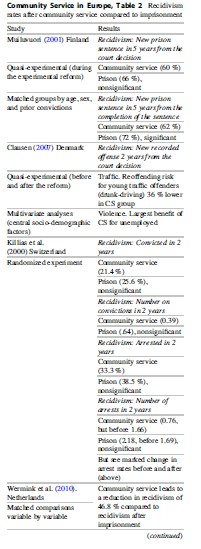

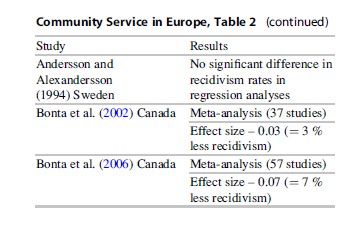

A Finnish study usedquasi-experimental design and compared two matched groups of offenders: onesentenced to community service in that part of the country where communityservice was in use on experimental basis, and the other group of offenders withsimilar background and convicted for similar offenses (mainly drunken driving,which has been the major offense in Finland for community service). Thefollow-up period was 5 years. Only new sentences leading to conditional orunconditional imprisonment or community service were counted as recidivism. Thestudy revealed a constant pattern showing that community service group hadfewer reconvictions throughout the follow-up period. The differences inreconviction rates varied depending on where the counting was started. Ifstarted from the court’s decision the difference after 5 years was 60 % forcommunity service and 66 % for prison group. If started from the completion of thesentence, the figures were 62 % and 72 %. And if counting of the follow-upperiod in the community service group starts from the court’s decision and inthe prison group from the release to parole (which would be sensible), thedifference in reconvictions would be 60 % (community service) and 72 % (prison, see Muiluvuori 2001) (Fig. 8).

In Denmark, Susanne Clausen (2007) has examined the preventive effect of community service compared to imprisonment. The study is limited to two offending categories: violent crime and traffic violations, including drunk-driving. In the case of traffic offenders, a change in the Danish penal code in 2000 made it possible to convert short prison sentences (up to 60 days) to CS. Capitalizing on this reform, Clausen compares recidivism levels between individuals sentenced to CS after the reform took place and those sentenced to unconditional imprisonment before the reform. As far as violent offenders, the quasiexperimental properties of the research design emanate from a change in the judicial policy that took place in the late 1990s. Within a relative short time period, the Danish courts increased the use of CS for violent offenders by a significant margin. In Clausen’s research, the treatment group consists of violent offenders sentenced to CS in 2000–2001 while the control group includes individuals sentenced to prison in 1997–1998. To further enhance the comparability between the offender groups, Clausen’s research controls for the impact of a large number of common risk factors, including age, gender, ethnicity, drug or alcohol misuse, mental problems, housing situation, education, employment, family type, and income. The subjects were tracked for 2 years for new crimes, starting from the date of conviction or release from prison (see Clausen 2007).

Findings from multivariate models suggest that, in general, characteristics like age, income, and prior criminality are more important as predictors of recidivism than the nature of the criminal sanction. On the other hand, the results provide some evidence of reduced recidivism associated with CS. For example, young traffic offenders (under age 25) were 36 % less likely to reoffend than those sentenced to prison. Among violent offenders, the unemployed seemed to benefit the most from community service. To explain these findings, Clausen suggests that CS protects young traffic, but also violent offenders from the stigmatizing from the stigmatizing effects of a prison sentence. On the other hand, by providing mandatory employment, CS may restore a sense of responsibility and routine for the previously unemployed offenders, thus enhancing their ability to reintegrate in the mainstream society. These benefits notwithstanding, Clausen’s study failed to confirm that CS helps to lower recidivism across most offender populations. The modest effects associated with CS may reflect the fact that it was compared to either conditional or very short prison sentences which, in most cases, are unlikely to create much damage. At the same time, there is little reason to suspect that CS will increase recidivism. Thus, to the extent it is less costly and considered more humane than prison sentence, it seems like an attractive alternative. In a methodologically advanced study, Killias et al. 2010a divided offenders randomly in community service and control group (prison). Recidivism was studied using four indicators: (1) whether offenders were convicted and (2) the number of convictions; whether (3) offenders were arrested and the (4) number of arrests. In addition, the authors compared how much the offenders had advanced, how many arrests they had before and after the sentence. By all measures, the community service group survived better. However, the small size of the sample kept the statistical significance rates low. In 2010, Killias and colleagues published evidence from two controlled, randomized experiments that assess the causal effect of community service and electronic monitoring on different post-sentencing outcomes (Killias et al. 2010a, b). While the first study (Killias et al. 2010a) finds no difference between community service and traditional custodial sentences, the finding of the second study (Killias et al. 2010b) suggests marginally significant differences between two types of noncustodial sanctions, electronic monitoring and community service, in favor of the former. However, the evidence is still relatively limited, particularly as most of the existing studies rely on rather small samples, which may explain the frequent result that the effects found are nonsignificant.

Problems related tosample sizes have been effectively avoided in a largest study based onlongitudinal official record data on adult offenders in the Netherlands (Werminket al. 2010). The study compares recidivism after community service to thatafter imprisonment with a sample of 4,246 offenders. To account for possiblebias due to the selection of offenders into these types of sanctions, a largeset of confounding variables was checked using a combined method of “matchingby variable” and “propensity score matching.” The findings demonstrate that offendersrecidivate significantly less after having performed community service comparedto after having been imprisoned. In relative terms, community service leads toa reduction in recidivism of 46.8 % compared to recidivism after imprisonment.This finding holds both on the short term and long term, and for male and femaleoffenders (Wermink et al. 2010) (Table 2).

The available evidencesuggests that community service is (at least) a promising alternative, in termsof reducing recidivism (using the Maryland University methodology scoring, see,for example, MacKenzie 2006). Several results point to significant differences betweenoffenders who are sentenced to imprisonment and offenders who participate incommunity service. The recent meta-analysis of Bonta et al. (2006) demonstratesa stronger effect size (.07) than earlier meta-analyses, which the authorsexplain by the better structured programs since 1995 considering “what-works”criteria (Bonta et al. 2006, p. 115).

In connection with community service, also other “non-reconviction benefits” need to be taken into account. These other beneficial features include positive contact to work life (and the resulting enhancement of offender’s economical situation), better self-control over substance abuse, and better preservation of family ties. “Importantly, results also indicate that community service participants fare better with regard to long-term social benefit dependency and income, especially when we disregard the possible effects of time trends” (Andersen 2012, p. 26). In addition, violent offenders and offenders convicted for misdemeanors showed lower recidivism rates than the imprisonment group. A problem, still deserving attention is how to deal with offenders, whose substance abuse prevents the use of community service. One answer is provided in the form of Swedish contract treatment.

Outlook: The Potential Of Community Service To Reduce The Prison Population And Increase The Reintegration Of Offenders

European sanction policies have been characterized by two different trends during the 1990s and 2000s: an increasing use of prison and the adoption of new community sanctions. The first one reflects the growing punitive and populist trends in national crime policies; the latter seeks to counteract this development by offering more constructive, rational, and humane substitutes to incarceration. The overall effect of the expansion of community sanctions may appear disappointing: The number of alternatives has grown along with the increasing number of prisoners. Neither does it seem that countries that use extensively community alternatives have – in general – lower incarceration rates. Still, it would be premature to conclude that the efforts to enhance the use of community sanctions have been futile. Some jurisdictions have gained true success, giving thus also information of the models that do work. Failures, on the other hand, may offer important lessons on what not to do. In short, community sanctions do provide one functional tool against the overuse of imprisonment, once a number of lessons from different jurisdictions have been drawn upon. The key questions are: (1) how to ensure that these sanctions are applied in the first place, (2) how to ensure that they come to replace imprisonment (instead of replacing other noncustodial sanctions), and (3) how to uphold and maintain the general credibility of these sanctions. Current problems and achievements have been summarized as follows (Lappi-Sepp€al€a 2003, see also van Kalmthout 2000):

1. Extra barriers should be constructed in order to ensure that the new alternatives are really used instead of imprisonment. In most countries, community service seems to substitute prison sentences only in roughly 50–60 % of cases. This rate can be improved by demanding directly – as is the case in Finland – that only prison sentences may be commuted to community service (leading to a “replacement rate” of over 90 % in Finland). Another way would be to define new alternatives as modes of enforcement of prison sentences, as has been done in Iceland.

2. Effective use of new alternatives and coherent sentencing practices require clear (statutory) implementation criteria. The courts should be given clear guidance as to when and for whom new sanctions are to be used. The role and position of new alternatives in the existing penal system (how they relate to other sanctions) should also be clarified.

3. The overall success of any community sanction requires resources and proper infrastructure. Community-based sanctions can only be applied within a community-orientated infrastructure geared to the specific requirements of these sanctions. Their implementation is dependent on the existence of an organization like the probation service. Often cooperation with private, semipublic, and public organizations or institutions is also required. The state and the local communities should provide the necessary resources and financial support.

4. Supervision, support, and swift reactions are needed in order to keep the failure rates down and to maintain the general credibility of new sanctions. The less control and supervision, the higher is also the dropout rate. There should also be a clear and consistent practice when the conditions of the sentence are violated. Varying and sloppy practices create mistrust and resistance on the part of public prosecutors, the judiciary, and the public.

5. Arrangements should be made in order to enhance the motivation of the offender for cooperation and mutual trust. New alternatives usually require the offender’s consent and cooperation. Treating the offender, not as a passive object of compulsory measures, but as an autonomous person, capable of reasoned choices, is a value by itself, and as such, it should be encouraged whenever possible. In addition, experience indicates that explicit and well-informed consent is a highly motivating factor for the offender. Through his/her consent, the offender has also become committed to the required performance in a manner that gives hope for good success rates.

6. Issues of equality and justice must not be neglected. Community sanctions may often lead to discrimination, since they are easily used for socially privileged groups of offenders. Measures must be taken to avoid social discrimination. Clear and precise implementation rules and procedures are one important means to this end. Another way is to tailor the system of community sanctions to meet the demands of different offender groups with their different problems. Sweden, for example, has a specific sanction – “contract treatment” – for those who suffer from drug or alcoholic addiction as a substitute for short-term prison sentences. Finland adopted in 2011 electronically monitored supervision order, supported by program work for offenders who are excluded from community service due to their addiction problems.

7. The idea has to be sold over and over again. Initial success does not guarantee that things will go well also in the future, just by themselves. Prosecutors and judges may lose their confidence, the enforcement agencies may lose their motivation, and the general public may withdraw its support. Maintaining the general credibility of the community sanctions and demonstrating their appropriateness is an ongoing process which does not end with the adoption of the requisite legislation and the arrangement of an initial training phase. The key groups, responsible for the implementation of the sanctions, must be given constant training and general information of the general benefits of community sanctions and the drawbacks of the wide use of custodial sanctions. Taking care of community relations is also important: The community should be informed of the benefits and crime control potential of community sanctions. Also the value of volunteer work needs a clear recognition. Finally, the practices must be subject to impartial scientific evaluation in order to obtain necessary information for further development.

8. Do not turn community service into a mere punishment in the community. The original objective of community service was to provide a socially constructive and less damaging alternative to imprisonment. Community service has rehabilitative and reintegrative potential, which must not be “sold” during the efforts to widen its applications and finding political support. Policy planners should resist the temptation of presenting community service to the public only as a “credible” and “demanding,” if not outright humiliating, alternative – as has taken place in some jurisdictions. Community service should be oriented toward the restorative justice and the rehabilitation ideal and implemented that way (which would be in line with international human rights standards) and not be left to penal populism and repressive orientations of “punishment in the community.”

Bibliography:

- Albrecht H-J, Sch€adler W (1986) Community service – a new option in punishing offenders in Europe. MaxPlanck-Institut fur ausl€andisches und internationales Strafrecht, Freiburg i. Br

- Andersson T, Alexandersson, L (1994) Samh€allstj€anst som alternativ till f€angelse. Utv€ardering av 1990- 1992 a˚rs fo¨ rso¨ ksverksamhet. BRA˚ -PM 1994:3.

- Andersen SH (2012) Serving time or serving the community? Exploiting a policy reform to assess the causal effects of community service on income, social benefit dependency and recidivism. University Press of Southern Denmark, Odense

- Bonta J, Wallace-Capretta S, Rooney J, McAnoy K (2002) An outcome evaluation of a restorative justice alternative to incarceration. Contemorary Justice rev 5(4), pp 319–338

- Bonta J, Jesseman R, Rugge T, Cormier R (2006) Restorative justice and recidivism: promises made, promises kept? In: Sullivan D (ed) The handbook of restorative justice: a global perspective. Routledge, New York, pp 108–120

- Clausen S (2007) Samfundstjeneste – Virker det? Juristog Økonomforbundets Forlag, København

- Council of Europe (2009) European Rules for juvenile offenders subject to sanctions or measures. Strasbourg, Council of Europe Publishing.

- Dunkel F, Lappi-Sepp€al€a T, Morgenstern C, van Zyl Smit D (2010) (eds.) Kriminalit€at, Kriminalpolitik, strafrechtliche Sanktionspraxis und Gefangenenraten im europ€aischen Vergleich. Mo¨ nchengladbach, Forum Verlag Godesberg.

- Dunkel F (2011a) Germany. In: Dunkel F, Grzywa J, Horsfield P, Pruin I (eds) Juvenile justice systems in Europe. Current situation and reform developments, vol 2, 2nd edn. Forum Verlag Godesberg, Mo¨ nchengladbach, pp 547–622

- Dunkel F (2011b) Ersatzfreiheitsstrafen und ihre Vermeidung. Aktuelle statistische Entwicklung, gute sentences on re-offending and social integration. J Exp Criminol 6, pp 115–130

- Killias M, Gillie´ron G, Kissling I, Villettaz P (2010b) Community service versus electronic monitoring – what works better? Br J Criminol 50, pp. 1155–1170

- Klement C (2010) Samfundstjeneste. En effektevaluering. Justitsministeriets Forskningskontor. http://www.justitsministeriet.dk/sites/default/files/media/Arbejdsomraader/Forskning/Forskningsrapporter/2011/Samfundstjeneste_-_En_effektevaluering.pdf. Accessed Aug 2011

- Lappi-Sepp€al€a T (2003) Fines. Community sanctions as a means to restrict the use of imprisonment? In: European Conference for Probation (Ed) Probation in Europe. Bulletin of the confe´rence permanente Europe´enne de la Probation, no 27. http://www. cepprobation.org/uploaded_files/juni%202003%20PDF%20format%2027%20-%20E.pdf Accessed June 2003

- Lappi-Sepp€al€a T (2008) Crime prevention and community sanctions in Scandinavia. Tokyo: UNAFEI (Annual report for 2007 and resource material series no 61). http://www.unafei.or.jp/english/pdf/RS_No74/ No74_00All.pdf

- Lappi-Sepp€al€a T (2012) Penal policies in the Nordic Countries 1960–2010. J Scand Stud Criminol Crime Prev 13:85–111. Praxismodelle und rechtspolitische U€ berlegungen.

- MacKenzie DL (2006) What works in corrections: reduc- Forum Strafvollzug – Zeitschrift fur Strafvollzug und Straff€alligenhilfe 60, pp 143–153

- Dunkel F, Pruin I, Grzywa J (2011) Sanctions systems and trends in the development of sentencing practices. In: Dunkel F, Grzywa J, Horsfield P, Pruin I (eds) Juvenile justice systems in europe. Current situation and reform developments, vol 4, 2nd edn. Forum Verlag Godesberg, Mo¨ nchengladbach, pp 1,649–1,716

- Dunkel F, Scheel J (2006) Vermeidung von Ersatzfreiheitsstrafen durch gemeinnutzige Arbeit: das Projekt “Ausweg” in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Mo¨ nchengladbach, Forum Verlag Godesberg

- Goldson B (2008) Dictionary on youth justice. Willan, Cullompton

- Heinz W (2012) Das strafrechtliche Sanktionensystem und die Sanktionierungspraxis in Deutschland 1882–2010 (Stand: Berichtsjahr 2010) Version: 1/2012’, Internet-Publication http://www.uni-konstanz. de/rtf/kis/Sanktionierungspraxis-in-Deutschland-Stand-2010.pdf

- Hildebrandt S (ed) (2012) Nordisk statistic for kriminalforsorgen I Danmark, Finland, Island, Norge og Sverige 2006–2010. Direktoratet for Kriminalforsorgen, Copenhagen

- de Jonge G (1999) Still ‘slaves of the state’: prison labour and international law. In: van Zyl Smit D, Dunkel F (eds) Prison labour: salvation or slavery? Dartmouth, Aldershot, pp 313–334

- Killias M, Gillie´ron G, Villard F, Poglia C (2010a) How damaging is imprisonment in the long-term? A controlled experiment comparing long-term effects of community service and short custodialing the criminal activities of offenders and deliquents. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Muiluvuori M (2001) Revidivism among people sentenced to community service in Finland. J Scand Stud Criminol Crime Prev 2(1), pp 72–82

- Space I (2010) Council of Europe. Annual penal statistics by Aebi M F, Delgrande N. University of Lausanne, Switzerland. http://www3.unil.ch/wpmu/space/files/ 2011/02/SPACE-1_2010_English1.pdf

- Space II (2010) Council of Europe. Annual penal statistics. Persons serving non-custodial sanctions and measures in 2010. Survey 2010, by Aebi MF, Marguet Y, Delgrande N. University of Lausanne, Switzerland. http://www3.unil.ch/wpmu/space/files/2011/02/Council-of-Europe_SPACE-II-2010-E1.pdf

- Tiffer-Sotomayor C (2000) Jugendstrafrecht in Lateinamerika unter besonderer Berucksichtigung des Jugendstrafrechts in Costa Rica. Forum Verlag Godesberg, Mo¨ nchengladbach

- van Kalmthout AM (2000) Community sanctions and measures in Europe: a promising challenge or a disappointing Utopia? In: Council of Europe (ed) Crime and criminal justice in Europe. Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, pp 121–133

- van Ness D (1986) Crime and its victims. Inter Varsity Press, Downers Grove

- van Zyl Smit D, Dunkel F (eds) (1999) Prison labour:salvation or slavery? Dartmouth, Aldershot

- Villettaz P, Killias M, Zoder I (2006) The effects of custodial vs. non-custodial sentences on re-offending: a systematic review of the state of knowledge. Campbell Syst Rev 2006, p 13

- Wermink H, Blokland A, Nieuwbeerta P, Nagin D, Tollenaar N (2010) Comparing the effects of community service and short-term imprisonment on recidivism: a matched samples approach. J Exp Criminol 6, pp 325–349

- Wright M (1991) Justice for victims and offenders: a restorative response to crime. Open University Press, Bristol

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.