This sample Desistance From Gangs Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Overview

Gangs present serious challenges to social and criminal justice institutions. The proliferation of gangs, coupled with their high involvement in criminal activity, fuels concern among citizens and policymakers alike. Indeed, gangs account for approximately one of five homicides in large US cities, and their members experience homicide victimization at rates 100 times greater than the general public (Decker and Pyrooz 2010). Further, gangs are a driving force for much of the nation’s gun crime as well as other pressing social issues (Howell 2007). The most recent law enforcement figures estimate that there are about 28,100 gangs and 731,000 gang members in the USA, demonstrating the scope of the problem (Egley and Howell 2011). Gangs continue to have a prominent presence in many neighborhoods, schools, communities, and families. As such, it is necessary to further understand both the characteristics and processes surrounding gangs and gang-related activity.

Despite the commonly held perception that gang membership is a lifelong commitment, most individuals that join gangs also leave gangs. In fact, involvement in gangs is typically short lived, with the majority of gang members remaining in their gang for 2 years or less (Krohn and Thornberry 2008; Pyrooz et al 2012). Involvement in gangs follows specific patterns: youth join gangs, they persist in gangs and participate in gang activities over some period of time, and then, more often than not, they leave their gang. That said, most research on gang membership has concentrated on either (1) the “ramping up” period of gang membership (i.e., when individuals enter into the gang trajectory) or (2) the persistence period of gang membership, focusing on the (mostly delinquent) activities of gang members. However, gang desistance – the process of exiting the gang – is an equally important aspect of gang membership. Indeed, hastening periods of gang membership will result in reduced rates of criminal offending and serious victimization.

This research paper examines the process of gang desistance. It begins by answering: what is gang desistance? In doing so, it illustrates and characterizes the concept of gang desistance, drawing from the larger debates and issues experienced in the life-course criminology literature. Next, it discusses the major parameters of gang membership: onset (joining the gang), duration (time spent within the gang), intermittency (the rejoining of gangs), and termination (de-identifying with the gang). It applies key concepts from life-course criminology – trajectories, turning points, and transitions – to the gang context, which helps bring meaning to the gang desistance process. This is followed by examining the primary dimensions of gang leaving, including the motives for leaving the gang, the methods by which gang members execute leaving, the abruptness or rate at which this process transpires, the role of continued social and emotional ties that are retained despite having left the gang, and the process of shifting identities. This research paper is concluded with a brief sketch of life after the gang, followed by a discussion on the importance of gang desistance research, the implications and benefits of understanding the many facets of gang desistance, and suggestions for future study, based on current gaps in the gang desistance literature.

Fundamentals

Gang desistance refers to the “declining probability of gang membership – the reduction from peak to trivial levels of gang membership” (Pyrooz and Decker 2011, p. 419). The component parts of this definition are derived from the life-course criminological literature (Kazemian 2007; Massoglia 2006), which decomposes desistance into two parts: (1) a reduction in the severity or frequency of participation in criminal activity and (2) an eventual, permanent end, or “true desistance” (Bushway et al. 2001, p. 492). Bushway et al. (2001, p. 500) stated that true desistance occurs when an individual’s rate of offending is “indistinguishable from zero” – in other words, when there is no empirical difference from non-offenders.

Gang desistance, however, differs from crime desistance in important ways. First, gang membership is a state, while offending is an event (Pyrooz et al. 2010). Granted the state of gang membership is comprised of a host of events that display group allegiance, similarly, the confluence criminal events could be conceived as criminal states. Yet, it is clear that gang membership implies at least some degree of connection to a group as opposed to events. To be sure, desistance from gang membership refers to leaving groups, while desistance from crime means disengaging from criminal behaviors. For instance, desisting from the gang does not necessarily mean desisting from crime, nor does the termination of offending indicate a disengagement from the gang. Groups have unique structures, a set of rules, defined roles, and activities; they also have “social cement,” a sense of cohesion within that specific group. In this sense, gang desistance is realized as individuals lessen their participation in group activities (e.g., meetings, social events, criminal events) as well as reducing the weight they place on the prominence of the gang and their identification with the gang, which leads to the second key difference between crime and gang desistance.

Operationally, gang membership is determined by self-nomination among study participants. In survey research, this typically takes on the following form: “Are you currently in a gang?” This measure has been found to be a “robust measure capable of distinguishing gang from non-gang youth” (Esbensen et al. 2001, p. 124). Those who have left the gang would have reported being a current gang member at some point in time, but no longer self-report gang membership. This is different from crime desistance because it is not necessary for “ex-criminals” to identify as having been a criminal. In other words, gang leaving is cognitive oriented in that it is determined by individual de-identification, while crime leaving is action oriented in that it is determined by individual behavior. This means that an individual can participate regularly in gang-oriented activities – flashing gang signs, recruiting and initiating new members, and selling drugs – but not be recorded as a gang member.

Criminal justice agencies, alternatively, determine gang membership differently than the research literature described above. Personnel in policing and correctional agencies focus on whether an individual meets a certain list of criteria to be entered into official gang databases. Self-reports are one of many measures that can exist for an individual to be entered into a gang database (Barrows and Huff 2009). In addition to self-report, it is common for agencies to consider gang-related tattoos, association with known gang members, flashing gang signs (observed directly or in pictures), the possession of gang paraphernalia, and information from informants. Those that meet two of the criteria are typically considered associates and those that meet three of the criteria are typically considered gang members. The number of necessary indicators and what attributes are included in the criteria vary between states (Barrows and Huff 2009). Leaving the gang, or getting removed from the gang database, is problematic because more emphasis has been placed on including rather than removing individuals in/from gang databases. As such, the regulation of gang databases and removing ex-gang members from such databases is a problem that criminal justice agencies will have to confront (Jacobs 2009). Regardless of the method of determining gang membership, there is movement both into and out of the gang. This movement is detailed in the following sections.

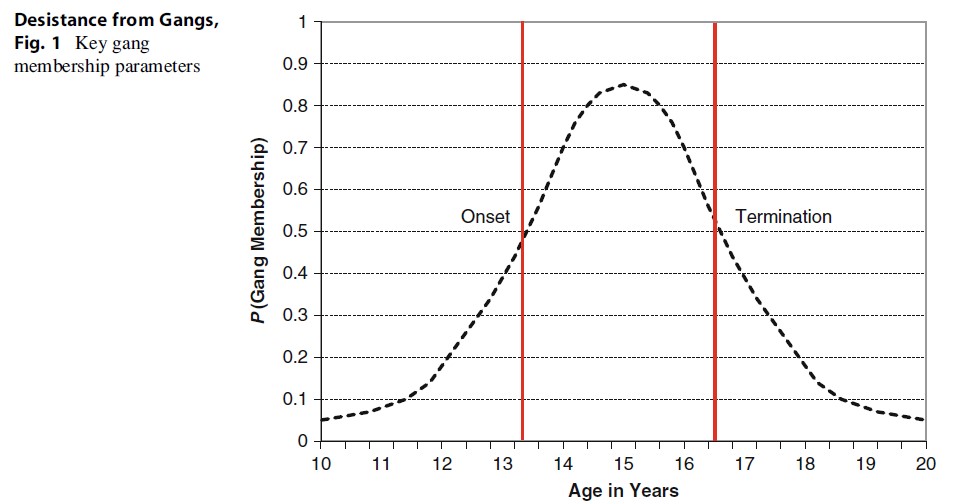

By defining gang desistance as a reduction in the probability of gang membership, it provides a broader view of the life course of gang membership in adolescence and young adulthood. In this sense, gang membership can be thought in terms of a distribution, with age along the x-axis and the probability of being in a gang along the y-axis. This is detailed in Fig. 1 using (somewhat) hypothetical examples of the intercept and slopes – or the points at which onset and termination occur. Gang desistance takes place from the peak level of involvement, the zenith of the curve around age 15, and slowly lowers to trivial level of membership around the late teens.

Couched with this hypothetical curve are two key parameters of gang membership: onset and termination. Onset refers to the first self-reported instance of identification with the gang. Termination refers to the first self-reported instance of de-identification with the gang. In relation to Fig. 1, these events boost or reduce the probability of gang membership above or below the 50 % threshold that would consider an individual a gang member.

In relation to life-course theory and research (Sampson and Laub 1993), onset and termination of gang membership take on added significance because they act as life-course transitions. Transitions are important events dotted throughout the life course that bring meaning to lives; events such as graduating high school, moving away to college, or having a baby are examples of significant events. Joining and leaving a gang are transitions because they are likely to constitute an important event in the life course. Moreover, these events are often formalized with getting “jumped into” or “blessed out” of the gang. Life events known as turning points, though, are key to understanding larger changes in the life course. Laub et al (2006, p. 314) noted: “turning points may modify trajectories in ways that cannot be predicted from earlier events.” These events redirect life trajectories in significant ways. Thornberry et al. (2003) argued that gang membership acts as a turning point in the life course. Melde and Esbensen (2011) recently demonstrated this empirically using a sample of youth from multiple cities in the USA. They found that not only did gang joining have a significant impact on criminal offending, but it also influenced the routine activities of gang joining youth. Further, gang membership had a negative impact on the attitudes, emotions, and social bonds of these youth, which led Melde and Esbensen to conclude that gang joining does indeed act as a turning point. These effects, however, were not reversed once one left the gang, so it remains an open question if gang leaving can put lives back on track.

Desistance from Gangs, Fig. 1 Key gang membership parameters

Desistance from Gangs, Fig. 1 Key gang membership parameters

Duration refers to periods between onset and termination. In other words, duration answers the question: how long do gang members remain in gangs? In relation to life-course research, gang membership can be thought of as a trajectory because it is sustained over a period of time. Sampson and Laub (1993, p. 8) defined a trajectory as a “pathway or line of development over the life span.” The gang trajectory is marked by formal periods of onset and termination, as noted in Fig. 1, but there are antecedent and ensuing connections to the gang – the latter is an integral dimension of the gang desistance process – which are denoted in areas below the curve yet above the x-axis.

To examine these time trends in the gang trajectory, it is necessary to have longitudinal data that systematically documents patterns of gang membership. Pyrooz et al (2012) reviewed a series of studies that examined the descriptive characteristics of continuity in gang membership, including the Gang Resistance Education and Training, Pittsburgh Youth Study, Rochester Youth Developmental Study, and Seattle Social Developmental Project (Thornberry et al. 2003). All of the aforementioned studies were carried out for at least 4 years and documented patterns of gang membership in Pittsburgh, Rochester, Seattle, and the 5-site G.R.E.A.T. study. In addition, Pyrooz et al. (2012) documented patterns of gang membership using longitudinal data collected in Philadelphia and Phoenix, based on the Pathways to Desistance study. As a whole, most youth did not remain in gangs for significant periods of time. The majority (48–69 %) remained involved with the gang for 1 year or less. Despite this, there was considerable variability around these figures, with 17–48 % reporting 2 years of membership, 6–27 % reporting 3 years of membership, and 3–5% reporting 4 or more years of duration within the gang.

Previous research, however, only documented the descriptive characteristics of gang membership duration. Pyrooz et al.’s study modeled this relationship to determine what factors impact continuity and change in gang membership. They found males, minorities (blacks and Hispanics), Phoenix gang members, individuals with poor self-control, and those more deeply embedded within their gang persisted over longer time periods. In fact, that one standard deviation higher in gang embeddedness – which includes for involvement, importance, status, position, and activities in the gang – was associated with at least 1 more year of gang membership. These are important factors to consider as it is well established that gang membership is strongly related to violent offending and victimization.

Intermittency refers to the leaving and subsequent rejoining of a gang. Two studies have examined intermittency – Pyrooz et al. (2012) and Thornberry et al. (2003) – finding that of the individuals that reported gang membership for multiple waves, about 57–66 % were intermittent gang members. In other words, these individuals would have joined a gang at least two times and left the gang at least one time. The extent to which this is an artifact of measuring gang membership or a reality in the streets is unknown. However, it is safe to say that intermittency poses hurdles for understanding the key parameters of gang membership and gang desistance research more broadly. The fact that intermittency exists is a testament to the view of gang membership as a dynamic process.

Kazemian (2007) believes it is reasonable to hypothesize that all criminal careers experience some level of intermittency across the life course, making the issue even more conceptually applicable to gang desistance. Intermittent participation in gangs may lead to an illusion of desistance, since ex-gang members may rejoin the gang at some later point in time or have varying levels of participation throughout the life course without entirely leaving. Most available data sets lack the ability – for criminal involvement and gang involvement – to rule out later rejoining of the gang; ultimately, measuring desistance based on non-offending simply does not suffice. Studies that have been done on desistance followed up on individuals within a relatively limited time period, thus possibly generating cases of false desistance that may have led to inaccurate conclusions about the desistance process thus far. However, the length of follow-up required to study true desistance is problematic, as studies would need to extend longitudinally throughout the entire life course in order to control for intermittency.

Thus far, gang desistance has been defined and identified by the key parameters (onset, termination, duration, intermittency) of gang membership. This section focuses on gang desistance processes, that is, key factors that characterize moving an individual from current to former gang membership status. It points out that this is a dynamic and evolving process that can be characterized by motives for leaving, methods for leaving, abruptness of the departure, the residual social and emotional ties that persist despite having left the gang, and changes in identities (see Pyrooz and Decker 2011). This section refers to these concepts as the dimensions of gang leaving.

Motives for leaving refer to reasons that influenced a gang member to exit the gang, and this dimension can be thought of as the subjective component in this process. Furthermore, motives for desistance can be organized in terms of push and pull factors. Push motives are factors internal to the gang that make persistence in gang membership undesirable. Typical push motives include “getting tired of the gang lifestyle,” “wanting to avoid trouble and violence,” and “getting tired of always having to watch my back.” The factors inspire one to seek out and select into other social arenas. Pull motives are factors external to the gang that steer or “yank” gang members away from the group. Typical pull motives include girlfriends, jobs, or children as the motivation for exiting the gang. Pyrooz and Decker found that about two out of every three gang members left their gang due to factors internal to the gang, or push factors. In other words, gang members didn’t leave the gang because of social interventions or jobs, but because of factors internal to the gang itself.

Methods for leaving refer to modes employed in order to exit the gang. In other words, how one was able to exit the gang and whether that exit was met with resistance. It is commonly believed that gang departures are synonymous with “blood in, blood out” – shedding blood to enter and exit the gang. In fact, it is often believed that the only way to leave the gang is by getting murdered or murdering one’s mother (Decker and Van Winkle 1996). While that might be an extreme example, it is not uncommon to hear that it is necessary to get “jumped out” of the gang. This process involves the “exiter” to have to endure punches, kicks, and other forms of interpersonal violence for a delimited time period. After these ceremonial actions, the individual is then “free to be on their way” having paid their debt to the gang. Another example of a departure method requires the exiter to commit a crime or a mission against a rival gang member. Many of these methods for leaving are similar to the methods for joining the gang (e.g., getting jumped in, going on a “mission”).

Pyrooz and Decker (2011) described the above departures as “hostile” in that an individual was forced to engage in some type of behavior to formalize leaving. Based on interviews with over 80 former gang members in Phoenix, they found that most gang members walk away from the gang without any repercussions. In fact, only 20 % of former gang members reported being met with some type of resistance. Importantly, especially for practitioners, is that the methods for departure are often conditioned by the motive for leaving. Pyrooz and Decker found that of the individuals that left the gang due to pull motives (e.g., pregnant girlfriend, job), none experienced a hostile method of leaving the gang. As a whole, hostile methods are more of a myth than a reality, which is not uncommon when studying gangs and gang-related behavior (Howell 2007).

Abruptness of departure refers to the rate at which the gang desistance slope declines. In other words, how long does it take to exit the gang after reaching peak levels of involvement? Further, once an individual decides to leave the gang, how long does it take until that process comes full circle? There are two main categories for describing the abruptness of this process: “knifing off” (Laub and Sampson, 1993) and “drifting off” (Decker and Lauritsen 2002). Knifing off is characterized by suddenly leaving the gang, which can be fueled by a significant event, such as the death of a friend as a result of gang violence. Drifting off takes places gradually as a result of shifting ties and social connections to the gang over a longer period of time. In essence, the desistance slope declines a slower rate for “drifters” and at a faster rate for the “knifers.” That said, Decker and Lauritsen (2002) found that it is more common for people to drift away from the gang rather than leaving quickly. Much of this is likely due to the natural progression from adolescence to adulthood where adolescents and young adults began to enter into new social arenas, continuing their education, taking jobs, and entering into relationships. These changes slowly disrupt social networks.

Continued ties persist despite having de-identified as being a gang member (Decker and Lauritsen 2002; Pyrooz et al. 2010). These ties to the gang can be both social and emotional; Decker and Lauritsen (1996) identified this as a “gray area” of leaving the gang. For example, some ex-gang members reported that they continued to hang out with the gang, participating in social activities such as drinking, smoking, and other social arrangement. Other ex-gang members reported that if their former gang was disrespected, they would respond to the disrespect. Similarly, if someone from their former gang network was assaulted, they would retaliate across rival gangs. Pyrooz et al. (2010) found that irrespective of how long an individual had left the gang, continued ties to the gang were associated with increased rates of violent victimization. In other words, the well-established pernicious effects of gangs persisted even if someone had renounced their allegiance.

Identity plays a rather obscure role in the desistance process, as it is not an easily observable dimension. However, gang members do use a number of outward symbols to identify themselves with their gang: hand signals, colors, tattoos, etc. The name of the gang also plays an important role in the gang member’s identity construct (Bjerregaard 2002). Desisting from a gang often means shedding these symbols to which the individual identifies so closely. Not only do ex-gang members have to go through both cognitive and identity restructuring processes, but they must also navigate through changes in their daily routine activities. As desisters move away from the gang, they establish new social ties in the greater society, and the activities that take up their time tend to shift from gang-related to what would be considered more normative outlets, such as school or sports. Much of the continued tie to the gang pertains to the labels that are attached to gang membership. That is to say, gang membership is in many ways a “master status” that is difficult to shake (Decker and Lauritsen 2002). There are key players involved in assigning that label, including (1) the self, (2) the gang, (3) the neighborhood, (4) the family, and (5) agents of the justice system. Note that throughout the progression from the self to the justice system, there is greater distance in awareness leaving the gang. In other words, while this decision begins with player #1, the remaining players can seriously impact – both positively and negatively – the decision to leave. Even if one has denounced their allegiance to the gang, that decision is formalized by the gang, and one is no longer socially and emotionally tied to the gang; this does not mean that their identity shifts are consistent with the views of the neighborhood or criminal justice agencies.

What about life after the gang? Two seminal contributions to the gang literature – Thrasher (1927) and Decker and Van Winkle (1996) – focus mostly on life in the gang, but what about life after the gang? Stated another way, what are the life circumstances of gang members 5, 10, or even 20 years after joining a gang? After exiting the gang, do the disruptive activities that characterize gang membership cease and give way to conventional lifestyles putting lives back “on track”? Or, do the disadvantages that accumulate during periods of gang membership have a lasting impact, posing additional difficulties for ex-gang members? Malcolm Klein (1971) noted in his book Street Gangs and Street Workers that “[a]lthough the need is great, there has been no truly careful study of gang members as they move on into adult status.” Fortunately, in the last 40 years since Klein’s critique, several studies have been able to address these issues.

Moore (1978) and Hagedorn (1998) reported on the adult lives of current and former gang members in East Los Angeles and Milwaukee. Both studies followed up on earlier ethnographic research (Hagedorn 1998; Moore 1978) and found that gang members did not fare well in their adult life. Moore found that while some male and female gang members settled down, started families, and pursued conventional employment, this was not the norm. She reported that high rates of early parenthood, unemployment, literacy barriers, and failed relationships made the transition from adolescence to adulthood difficult for many individuals. Hagedorn found that his subjects had dismal high school graduation rates, high rates of unemployment, a reliance on illicit underground markets for income, a dependence on state welfare, and had children at young ages; nearly nine of ten female gang members were mothers in their early twenties. Both researchers relied heavily on Wilson’s (1987) hypothesis regarding the impact of deindustrialization and concentrated disadvantage. They argued that their subjects, unlike earlier generations, were shut off from bluecollar job opportunities and thus relied on gang membership, illegitimate labor markets, and entry- and service-level employment for support.

Levitt and Venkatesh (2001) studied gangs operating in Chicago housing projects in 1991. They followed up on the members of their sample, which included gang and non-gang members, in 2000 to examine a host of outcomes and related changes that occurred over that 9-year period. Based on the 2000 interviews, Levitt and Venkatesh examined the effect of gang membership on nine life outcomes, including high school graduation; employment; current incarceration; ever incarceration; annual total, legal, and illegal income if not incarcerated; number of times shot; and housing project resident. The results of their analyses revealed that the negative outcomes tied to gang membership were associated with crime (incarceration, incidence of gunshot victimization, illegal income) rather than other social domains (high school graduate, current employment, public housing residence). This distinction between involvement in prosocial activities and involvement in crime is important for youth policy in general and gang policy in particular. The results suggest that gang membership has little impact on participation in prosocial activities, but long-term negative effects on involvement in crime and victimization.

Thornberry et al. (2003) and Krohn et al. (2011) followed a sample of about 1,000 at-risk youth attending middle schools in Rochester, NY, until their late twenties and early thirties. They argued that gang members would be less successful in accomplishing normative transitions from adolescence to adulthood, such as graduating high school and attending college, than youth who did not join a gang because of their involvement in “precocious” behaviors and risky activities. From their perspective, gang membership can be viewed as cutting off or limiting possibilities for youth, particularly in the key areas of education and employment. The outcomes these studies examined included high school dropout, teenage parenthood, early nest leaving, adult unemployment, welfare dependence, interpersonal problems in the household, cohabitation, adult offending, and adult arrest. Gang membership influenced all of these outcomes positively, increasing the likelihood of their occurrence. These findings, however, were stronger for male gang members and persistent gang members, compared to their female and transient counterparts.

Finally, Pyrooz (2012) explored the educational, economic, and employment trajectories of youth, focusing on the impact that adolescent gang membership had on these trajectories in early adulthood. He found that joining a gang had an immediate impact on educational attainment, particularly for graduating from high school and matriculating to college. While the differences in high school graduation lessened over time, gang joiners were less likely to attend college and earn a 4-year college degree. In summary, the net effect of gang membership on educational attainment was one-half year. That might sound minimal, but that was the difference between graduating from high school or not, as gang joiners completed 11.5 years of education compared to the 12 years completed by their similarly situated counterparts. Educational attainment had consequences for employment, where Pyrooz observed that gang members were jobless for longer periods throughout the year. While gang members, when working, earned as much and worked as many hours as nongang individuals, over a 6-year period, they made $14,000 less because of their inconsistent patterns of joblessness.

In summary, this research paints a gloomy picture for the adult lives of adolescent gang members. This implies that the well-established consequences of gang membership are not entirely limited to the short term. That is, gang membership has lasting consequences that (1) extend across the life course and (2) cascade into other significant life domains, such as marriage, family, employment, and education. These consequences could impact not only the rates at which gang members desist from the gang but also complicate the motives and methods for desistance as well as the residual ties that persist after leaving.

Future Directions

This research paper has explored a series of issues pertaining to leaving gangs. It has provided both conceptual and operational definitions of gang desistance, identifying key issues in the research literature. It explored the parameters of gang membership – onset, termination, duration, and intermittency – and, in doing so, placed these parameters in the broader context of the life course. The key portion of this research paper detailed the multiple dimensions of leaving the gang. These dimensions include the motives for leaving, the methods for leaving, the abruptness of desistance patterns, the continued ties after leaving, and the process of identity reconstruction for ex-gang members. Based on what has been discussed above, there are several key conclusions that may help provide directions for future research.

First, leaving the gang is a dynamic and evolving process, one that takes time to realize fully. This process involves factors that push and pull the gang member away from the nucleus of the gang – van Gemert and Fleisher (2005) refer to it as the “grip of the group” – helping to shred the social and emotional ties to the gang. However, notification of leaving the gang travels across key social players and paths at different rates: from the individual, to the gang, to the neighborhood, to the family, and finally, to the police. As this information transfers across each of these paths, there is the possibility for resistance and pushes and pulls back into the gang. For example, if a gang member on the desistance pathway was arrested in suspicion of committing a crime, he or she would be housed in a county jail facility – both jails and prisons are typically hotbeds for gang activity. This gang member would likely be segregated out of the general population into a pod consisting of non-rival gangs and likely fellow gang members, which could result in strengthened ties and increased embeddedness. Further, past antagonisms between former rival gangs may persist, and victimization may push one back into the gang lifestyle. To be sure, it may take several attempts before a gang member is able to break free from the group processes associated with gangs. Identifying intervention points where gang members’ ties to their gang are weak, during violent episodes or after someone has “snitched,” may be key to influencing decisions to leave, especially since internal factors appear integral to leaving the gang. Understanding these processes – especially with regard to complicating leaving the gang – should be a central task of gang researchers.

Second, leaving the gang might not be associated with benefits or virtues symmetrical to the impact of joining the gang. That is, while joining a gang can be viewed as a turning point in the life course due to wide-ranging negative effects, leaving the gang does not appear to necessarily return lives to the previous “unblemished” state. In this sense, the gang environment “takes on a history of its own” (Laub and Sampson 1993, p. 320) in that it changes lives in important ways. One might expect that while escaping the expectations of the group should decrease rates of criminal offending and victimization, the deficits accumulated during periods of gang membership may overwhelm any gain achieved from leaving. Nevertheless, given the robust overrepresentation of gang members in self-report and officially recorded rates of offending and victimization (Curry et al. 2002; Thornberry et al. 2003), it is probably no coincidence that the age-crime curve and the age-gang membership curve are tapering off at comparable or parallel rates. Despite the possibility that leaving the gang may not be associated with the drop in crime that is equivalent to gang joining, hastening periods of gang membership should remain a high priority given what is known about the serious consequences of gang membership in individual lives and gangs in communities.

Third, “desistance” is a process not unique to the gang context. The gang literature has drawn heavily from life-course criminology to aid in the development of gang desistance research. Yet, as Ebaugh (1988) noted, role exits contain a great deal of continuity across important life states, including retiring or switching careers to changing genders to leaving the religious convent. In other words, whether one is studying differences between exiting conventional and deviant networks or exiting within deviant network types, there are likely to be universal factors that characterize the exit. To be sure, leaving groups and roles is a global phenomenon. Ebaugh refers to four parts in the exit process, including (1) initial doubts, (2) seeking role alternatives, (3) turning points, and (4) establishing an “ex” identity. Understanding variability in these patterns within and across groups would bring a greater understanding to the difficulties in these processes and, ultimately, assist policies to help or hinder such exits. In the gang context, for example, are there organizational structural characteristics – such cohesion, hierarchies, or collective action (Decker and Pyrooz 2011) – that promote longer periods of gang membership? Or, are there characteristics of the gang that meet attempts to leave with serious resistance? Informal social controls in the group context will likely lend considerable insight into exit and desistance processes.

In the attempt to further develop an understanding of gang desistance, this research paper has summarized and expanded on the current state of the gang desistance literature. In doing so, it has identified key concepts in the process of desistance and, in some cases, comparing these processes to research on crime desistance in the life course. Leaving the gang is a dynamic process that is not only characterized by motives and methods for leaving but also by broader factors that take place long before and after exiting the gang. This process has not received attention from the research community equal to the process of joining a gang, despite the equally important implications. Future research should further develop, both theoretically and empirically, the concepts and findings discussed in this research paper.

Bibliography:

- Barrows J, Huff CR (2009) Gangs and public policy. Criminol Public Policy 8:675–703

- Bjerregaard B (2002) Self-definitions of gang membership and involvement in delinquent activities. Youth Soc 34:31–54

- Bushway SD, Piquero AR, Broidy LM, Cauffman E, Mazerolle P (2001) An empirical framework for studying desistance as a process. Criminology 39: 491–516

- Curry GD, Decker SH, Egley A (2002) Gang involvement and delinquency in a middle school population. Justice Q 19:275–292

- Decker SH, Lauritsen J (2002) Leaving the gang. In: Ronald Huff C (ed) Gangs in America, 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Decker SH, Pyrooz DC (2011) Gangs: another form of organized crime? In: Paoli’s L (ed) Oxford handbook of organized crime. Oxford University Press, New York

- Decker SH, Van Winkle B (1996) Life in the gang: family, friends, and violence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Ebaugh HRF (1988) Becoming an ex: the process of role exit. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Egley A Jr, Howell JC (2011) Highlights of the 2009 National Youth Gang Survey. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Washington, DC

- Esbensen FA, Winfree LT, He N, Taylor TJ (2001) Youth gangs and definitional issues: when is a gang a gang, and why does it matter? Crime Delinq 47:105–130

- Hagedorn JM (1998) People and folks: gangs, crime and the underclass in a rustbelt city, 2nd edn. Lakeview Press, Chicago

- Howell JC (2007) Menacing or mimicking? Realities of youth gangs. Juv Fam Court J 58(2):39–50

- Jacobs JB (2009) Gang databases: context and questions. Criminol Public Policy 8:705–709

- Kazemian L (2007) Desistance from crime: theoretical, empirical, methodological, and policy considerations. J Contemp Crim Justice 23:5–27

- Klein MW (1971) Street gangs and street workers. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

- Krohn MD, Thornberry TP (2008) Longitudinal perspectives on adolescent street gangs. In: Liberman AM (ed) The long view of crime: a synthesis of longitudinal research. National Institute Of Justice, Washington, DC

- Krohn MD, Scmidt NM, Lizotte AJ, Baldwin JM (2011) The impact of multiple marginality on gang members and delinquent behavior for Hispanic, African American, and White Male Adolescents. J Contemp Crim Justice 27:18–42

- Laub JH, Sampson RJ, Sweeten G (2006) Assessing Sampson and Laub’s life-course theory of crime. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins K (eds) Taking stock: the status of criminological theory, vol 15, Advances in criminological theory. Transaction, New Brunswick

- Levitt SD, Venkatesh SA (2001) Growing up in the projects: the economic lives of men who came of age in Chicago public housing. Am Econ Rev 91:79–84

- Massoglia M (2006) Desistance or displacement? The changing patterns of offending from adolescence to young adulthood. J Quant Criminol 22:215–239

- Melde C, Esbensen FA (2011) Gang membership as a turning point in the life course. Criminology 49:513–552

- Moore JW (1978) Homeboys – gangs, drugs, and prison in the barrios of Los Angeles (CA). Temple University Press, Pennsylvania

- Pyrooz DC (2012) The non-criminal consequences of gang membership: impacts on education and employment in the life-course. Doctoral dissertation, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Arizona State University

- Pyrooz DC, Decker SH (2011) Motives and methods for leaving the gang: understanding the process of gang desistance. J Crim Justice 39:417–425

- Pyrooz DC, Decker SH, Webb VJ (2010) The ties that bind: desistance from gangs. Crime Delinq. Online First. doi:10.117/0011128710372191

- Pyrooz DC, Sweeten G, Piquero AR (2012) Continuity and change in gang membership and gang embeddedness. J Res Crime Delinq. Online First. doi:10.1177/0022427811434830

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

- Thornberry T, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Smith CA, Tobin K (2003) Gangs and delinquency in developmental perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Thrasher FM (1927) The gang: a study of 1,313 gangs in Chicago. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- van Gemert F, Fleisher M (2005) In the grip of the group. In: Decker SH, Weerman FM (eds) European street gangs and troublesome youth groups. AltaMira, Lanham, pp 11–30

- Wilson WJ (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.