This sample Effective Community Supervision Programming Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Overview

This research paper describes and discusses aspects of a comparatively recent innovation in criminal justice services, which has taken hold in a number of countries: the development and implementation of structured programs designed with the specific purpose of reducing the recidivism rates of participants. While such programs have been delivered both in prison and community settings, the present entry focuses primarily on the latter. Following an introduction of some basic concepts, the paper provides an account of the theoretical rationale that underpins this departure, and reviews sources of evidence on the principle of risk-need assessment which has informed the choice of methods and contents used in programs of this type. This is illustrated with reference to some well-established types of program, before turning to a discussion of some of the practical issues arising from engaging in work of this type.

Several key issues are then examined, including the following: the evaluation of program use and the outcome evidence so obtained, both from controlled experiments and following large-scale dissemination; the quality control of programs through accreditation processes; and the organizational context within which programs are delivered – what have been called nonprogrammatic influences. This is followed by a review of some of the implications of these results, focusing in particular on the capacity of community supervision to absorb larger numbers of offenders through transfer of resources from custodial sentences, in a process that has been labeled “justice reinvestment.” There is some brief discussion of strategies for enforcement of community supervision, and this research paper concludes with discussion of some outstanding issues and controversies arising in this area.

The Emergence Of Structured Programs

This research paper will focus on one relatively recent development within the process of probation or community supervision: the advent and widespread dissemination of structured programs. These involve offenders in participatory, preplanned activities with the objective of enabling them to reduce their likelihood of committing further crimes. It is difficult to identify an exact date when this specialized type of practice arrived on the probation scene, but as an approximation it can be traced to the mid-1980s and the appearance of a number of publications which ran counter to the then prevalent belief that “nothing works”: that there was no realistic prospect of successfully achieving offender rehabilitation. During that era, many legal systems were still imbued with an ethos informed by the erroneous impression created by research published in the 1970s, suggesting that persistent offending behavior could not be modified and that what had previously been called rehabilitation or reform of offenders was not practically feasible (Gaes 1998). Mounting evidence since then has contradicted those suppositions, and the return of what is loosely and perhaps misleadingly called “treatment” to the criminal justice arena further strengthened interest in and adoption of programs.

Probation or other community-based supervision of offenders was traditionally centered on humanitarian concerns, and the probation officer’s principal role was to address the individual’s personal and moral well-being. At a later stage, more concrete matters such as employment, accommodation, financial or family problems came to the fore, and supervision became more practical in its focus. Despite that switch of emphasis, behavior change was still thought to be accomplished largely through a relational process, and in that respect, working with individual offenders was considered to have similarities to counseling or psychological therapy. Thus, there was an accent on the supervisor’s ability to develop a working relationship with offenders. It had always been realized that alcohol and other substance abuse disorders were associated with criminal offending, but as substance abuse became a problem in many societies and its close association with criminal offending came to be understood better, the incapacity of relational models to succeed in addressing and resolving such problems began to be exposed. Furthermore, as cost-conscious governments focused more on the accountability and cost-effectiveness of public services, community supervision agencies were carefully scrutinized regarding offender outcomes. This was paralleled by an emphasis on risk assessment, risk management, and public protection as core duties of community supervision staff.

The precise sequence whereby programs were adopted as a component of working with offenders is difficult to chart. Supervision became incrementally more structured, first through the advent of task-centered casework and an expansion in the use of group work, followed by the gradual emergence of greater explicitness and structure in the work that was done. The majority of the programs to be discussed here are delivered in small groups within which the climate takes less of a therapeutic inclination than of one that has more similarities to an educational process or a training session. However, relationships between participants and the role of the tutor or leader as a facilitator of collective learning still play a crucial, if underappreciated, part.

In this research paper we will first consider definitions of some key terms. We will then consider the background and theoretical models that have influenced the development of programs, before looking more closely at the composition of some of the programs themselves. This will be followed by a review of how they are applied in practice and the kinds of findings that have been obtained from evaluations of their use. It is now widely accepted that programs alone are only part of effective services; therefore, we will also look briefly at what are called “nonprogrammatic” factors. Finally, there will be some discussion of outstanding and unresolved issues that still challenge this field.

Fundamentals

In what follows, several aspects of community-based programming will be discussed. A useful starting point is to consider definitions and the features that the specialized activities known as structured programs have in common. The word program as used in this context refers simply to a planned sequence of learning opportunities that can be reproduced on successive occasions (McGuire 2001). In criminal justice settings, its general objective is to reduce participants’ subsequent criminal recidivism. Within that context, the typical program is a set of activities prepared in advance, with clearly stated objectives, and comprises a number of elements interconnected according to a planned design and with a demonstrable link to those objectives. So these are sometimes referred to as “structured” programs, to distinguish them, for example, from therapeutic communities which have preplanned elements but a lower level of detailed specification of content. For methods and exercises to be reliably replicated on successive occasions, they need to be described and recorded in an accessible, manual format that correctional practitioners will readily understand. Such “manualization” – essentially, preparing program materials in a portable form that would be readily usable on repeated occasions by those delivering them – has become a standard aspect of the use of programs. This has allowed critics of the movement towards programs to allege that supervision has been mechanized and that there has been a neglect of individual needs, where the use of structured methods instills a monolithic “one size fits all” approach.

If correct this would be a legitimate concern, but two responses can be made to it. First, program manuals vary considerably in the amount of detail they contain and in their level of prescriptiveness. Whereas some specify the minutiae of the actions of facilitators on an almost moment-by-moment basis (even, e.g., providing the text of statements made to participants at various points in the process), others are loosely or schematically formulated, affording sizeable latitude in how a method should be applied or a skill-training exercise should be run. This creates scope for adaptations to be made to take account of diversity among participants. It also creates opportunities for facilitators to exercise discretion as to the details of how sessions should be run, drawing on their own experience and their judgments of a group, though this must be kept within specified limits if the integrity of the program is to be preserved. Second, programs are not seen as solutions in themselves but as just one part of the overall supervisory process. In most contexts, participation in a probation program generally lasts for only a few weeks, usually at the commencement of a community sentence. Thus, a larger portion of time remains during which the individual’s primary contact with the criminal justice system is through his or her probation supervisor. While supervising officers are not generally involved directly in program delivery, they should be aware of the nature and contents of programs their supervisees have attended. Thus, while a program should have a direct impact, it should also work as a catalyst for the longer-term supervisory experience and should instigate an orientation whereby learning and change can be sustained and an individual is motivated and equipped to continue working on problems he or she has identified.

Background Research And Theory

The growth of interest in programs and their dispersal was probably stimulated and sustained by research showing that individuals, even those with extensive criminal histories and apparently entrenched patterns of antisocial attitudes and behavior, are capable of change: efforts at “rehabilitation” can and do work. The pessimistic stance that dominated the correctional enterprise for two decades or so, commencing approximately in the mid-1970s, is now widely acknowledged to have been based on a number of errors and misinterpretations of the data that were extant at that time. Some scholars raised those points contemporaneously and challenged the escalating punitive ethos (e.g., Gendreau and Ross 1980). Since then, however, far more evidence has accumulated on this and related points.

The introduction of structured programs as a component of community supervision of offenders was grounded on the premise that such a development would have a discernible impact in reducing criminal recidivism. As a response to the controversies of an earlier era and the dismissal of rehabilitation from correctional discourse and practices, what is colloquially known as the “what works” research began to flourish from the mid-1980s onwards. This consists of a considerable volume of primary studies in which selected programs are evaluated with respect to their effects on re-offending rates of participant offenders, usually measured against an “untreated” or “business as usual” comparison group. The results of such studies have subsequently been integrated in surveys of research typically involving use of the statistical techniques of meta-analysis or systematic review.

There has been a steadily expanding number of such reviews of designated portions of this literature (McGuire 2008). At the time of writing, this comprises no fewer than 100 relevant meta-analyses of programmatic interventions (McGuire 2013). This excludes evaluations of other criminal justice approaches such as changes in legal procedures or in sentencing practices, situational crime-preventive measures, treatment of substance abuse conducted in healthcare settings, studies that focus purely on medical interventions, or interventions focused wholly or primarily on children below the age of criminal responsibility.

An overview of these findings reveals that on average, interventions yield a net reduction in offender recidivism that is modest, though statistically significant. This average figure is however somewhat higher when punitive interventions (which have either zero or negative effects) are excluded from it. More importantly, there are consistent patterns within the positive results that remain, such that there is justification for the claim that appropriately designed interventions can lead to reductions in subsequent recidivism of the order of 20–25 %. A proportion of the programs reviewed by Lipsey et al. (2007) which exhibited features of “best practice” produced an effect size (using the odds ratio statistic) equivalent to a reduction in recidivism among experimental as compared to control groups of 52 %.

There is a close association between background research, theoretical precepts, and everyday practice in the design of offending behavior programs (see, e.g., McGuire 2005). Their content is not derived from the now discarded notion that general differences can be found between samples of offenders and non-offenders. The concept of there being a distinctive “criminal personality” has been largely abandoned, and it is recognized that a majority of citizens break the law at some stage of their lives. At the same time tentative propensities towards involvement in crime may be unevenly distributed, and as a consequence of an interaction between temperament, socialization processes, and environmental variables, some individuals may be more likely to become repetitively or persistently involved in criminal conduct. Such a pattern has been found in many longitudinal and survey studies (Andrews and Bonta 2010), and models have been forwarded concerning the possible distinguishing features of those more prone to delinquency. Research and theory therefore focus more closely on identifying patterns within this variation.

This has led to the emergence of a model of criminal involvement focused on “risk factors,” which are aspects of individual functioning that have significant and consistent associations with the likelihood of arrest and rearrest. Those most frequently discovered from both longitudinal studies and from meta-analysis of cross-sectional and treatment-outcome studies include the following: having a large proportion of associates who are involved in delinquency; low levels of self-control, with a tendency to be impulsive; antisocial attitudes and beliefs; and poor or underdeveloped skills in interpersonal problem-solving and social interaction. These are often conjoined with substance abuse and in a proportion of cases with other features of antisocial personality. When working with any given individual, it is considered essential to assess him or her with reference to the aforementioned risk factors, and a range of methods has been developed for undertaking this.

The nature of these associations and the causal pathways involved between them has been most clearly formulated in the risk-needs-responsivity (RNR) model (Andrews and Bonta 2010), which remains the principal theoretical model informing the design of programs. This model draws on concepts from social learning theory developed by Albert Bandura and others, with concepts of socialization and family influence as discovered in the work of the Oregon Social Learning Center and with other findings of developmental and life-course criminology. To an extent these ideas constitute a convergence of social learning theory and control theory as conceptualized in criminology but are further enriched by an understanding gained from research in personality and social psychology on the nature of person-situation interactions, differential associations, and the development of regular patterns of social cognition and self-appraisal.

Intervention methods that flow from this theoretical viewpoint are fundamentally grounded in the expectation that the patterns just described are largely (though not exclusively) products of development and learning. On that basis it is deduced that they can also be redressed by acquisition and application of new skills that will enable individuals to encounter high-risk situations and successfully negotiate a route through them without resorting to a criminal act. The central tenet of the attempt to achieve this is the realization that cognition (thoughts), emotion (feelings), and behavior (actions) are three discrete domains of activity and experience that are interdependent and in a constant state of interplay and mutual influence. Furthermore, there is also a causal (bidirectional) interplay between them and environmental events, a model called reciprocal determinism. Another way of describing this is to say that individual behavior and experience are a function of personsituation interactions.

The behavioral components of the programs derived from this draw on the fundamental principles of learning theory and the application of classical and instrumental conditioning to therapeutic change. The behaviorism of B. F. Skinner and other researchers is revised to incorporate social learning concepts such as modeling and internal representation thereby learning, e.g., about the effects of peer-group pressure, and acquiring skills of assertiveness to resist it. The cognitive components focus on the relationship between “automatic” and “controlled” processing of information, thought to lead to habitual patterns in the ways individuals perceive themselves and others, think about difficulties they are facing (or avoid doing so), and solve problems (or allow them to accumulate).

Program Designs And Contents

A majority of successful programs used today exploit some permutation of methods originating from cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). This is a theoretically driven, psychologically based approach to the amelioration of a broad spectrum of individual and family problems, covering the whole life span. The approach is widely used in education, mental health, and other services and to date remains the best researched and most firmly “evidence-based” of the different treatment models available in those fields. Variants of it have been adapted for use in criminal justice services. This is, however, by no means the only model that has been utilized in program designs, simply one that has become dominant as a result of a larger volume of published evaluation research.

The following are some examples of programs that are among the most widely used, some in adapted forms in prison as well as community settings. Fuller descriptions of many programs can be found in Hollin and Palmer (2006).

Reasoning and Rehabilitation: Usually simply called R&R, this is the longest established and most extensively employed program of this type. Developed in Canada, it has reportedly been used with over 50,000 offenders in 17 countries (Antonowicz 2005). It consists of 38 sessions of 2 h each, covering a range of modules devoted (among others) to problem-solving, emotional control, negotiation training, values enhancement, creative thinking, and critical reasoning.

Enhanced Thinking Skills (ETS) is an abbreviated, 20-session version of R&R developed in the prison service of England and Wales but later used in probation, focusing mainly on problem-solving, self-management, and victim perspectives.

Think First: This is prepared in several variant forms for use in probation, prisons, and youth justice, respectively. The program is designed so that identified risk factors for criminal recidivism are focused on in successive phases (moving from problem-solving through self-management to social interaction skills, attitudes, and values) and progressively combined to enable participants to address different aspects of their offenses. Sessions incorporate analysis of offending behavior itself, that is, the sequence of events that occurred when an individual committed an offense, and what he/she was thinking and feeling at the time. This work is carried out in detail for each group member’s most recent or most serious offense, then repeated across several incidents to examine any patterns that emerge.

Developed to work with groups with histories of a variety of criminal behaviors (individuals regarded as “versatile” offenders), the above three programs are sometimes called general offending behavior programs. Other programs however address specific types of offense, usually of a more serious (e.g., violent or sexual) nature, or with a more pronounced pattern in an individual’s criminal history (e.g., substance misuse).

Several structured behavior change programs have been developed with a focus on recurrent violent offending. They include Aggression Replacement Training, an 18-session program initially developed for youth in the United States but more recently used with adults. It directs participants’ attention to three aspects of events where they may have committed offenses, those of self-control (“what not to do”), social/ interpersonal skills (“what to do”), and moral reasoning training (“why to do it”). For those with longer established patterns of serious violence, the Cognitive Self-Change Program may be used. Initially developed in prisons in Vermont, it is designed for individuals with a history of personal assaults who wish to address and alter their pattern of behavior; it involves 38 sessions lasting 2–2½ h. Where an individual’s violent reactions are thought to derive from difficulties in anger control, many programs are available, including Controlling Anger and Learning to Manage It (CALM), a 24-session program focusing intensively on enabling individuals with histories of angry aggression to acquire skills in self-management of angry feelings.

There is a portfolio of programs now available for individuals who have committed sexual offenses. The Sexual Offender Treatment Programme (SOTP) entails a suite of five programs designed for the reduction of sexual offending, with forms available for use in both prisons and community. The original version was an intensive, multimodal intervention for use in prisons and comprised several versions for individuals varying by level of risk and level of functioning, together with supplementary sessions designed as “booster” or maintenance exercises. In England and Wales there are also several probation-based variants.

Substance Misuse Programs: Numerous programs have been developed to address substance abuse both in health and criminal justice settings. They differ according to their target problem (e.g., alcohol, illegal drugs), their planned outcome (abstinence, control), and their intensity (number and duration of sessions). Many include follow-up activities focused on relapse prevention for which there are additional methods and materials employed. Still others are designed for specific offenses arising from substance abuse, such as programs for driving while intoxicated, or for alcohol-related aggression.

Application And Dissemination

The majority of the studies reviewed in the metaanalyses briefly summarized above were conducted on a comparatively limited scale and often, though by no means always, under fairly well-controlled conditions. The question therefore arises as to whether similar findings can be secured when interventions of this type are propagated, organized on a larger scale, and assimilated into routine practice. Impressed by the findings, governments of several countries embarked on policy experiments in which specially designed programs or other services were introduced into community supervision (and in some instances also prison) sentences. Programs have been in use in many countries, in locations as far apart as the United States, Canada, England and Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Norway, Estonia, Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Chile, Hong Kong, Australia, and New Zealand. In England and Wales, which has perhaps gone farthest in this direction, this formed part of a large-scale policy initiative, the Crime Reduction Programme, which was made operational from 2000 onwards. It entailed the gradual installation of structured interventions (designated “Pathfinder” programs) at many probation sites and an extensive menu of staff training to deliver them.

Given the plethora of program types, by the late 1990s the field of corrections rather quickly took on the appearance of a marketplace in structured interventions. As part of the drive towards transparency and accountability, some justice departments developed standards that programs were required to meet before they could be approved for use in justice services. The adoption of programs was accompanied by the establishment of “accreditation” processes to select the methods thought most likely to reduce recidivism. In England and Wales, an elaborate system was created for monitoring standards of delivery and evaluating outcomes. This led to the establishment of an independent group of expert consultants, currently called the Correctional Services Advisory and Accreditation Panel (CSAAP). The Panel devised a procedure for evaluating the suitability of programs and published a set of accreditation criteria for that purpose (Correctional Services Accreditation Panel 2010). Programs submitted to the Panel for accreditation are judged in terms of a set of 10 criteria, specifying that they should meet the following requirements:

- A clear model of change: The program is based on a clear, explicit model of change with a sound basis in a broader theoretical framework.

- Selection of offenders: There are clear and appropriate criteria for the selection and allocation of those who should take part.

- Targeting a range of dynamic risk factors: The program’s materials and methods must target a range of dynamic risk factors, that is, the program is multimodal in format and content.

- Effective methods: The program entails use of demonstrably effective methods of intervention, derived from relevant research literature.

- Skills orientated: Methods used in the program focus on the acquisition and development of relevant skills to enable individuals to avoid re-offending.

- Sequencing, intensity, and duration: There are clear, explicit links between the sequencing, intensity, and duration of the program’s separate components.

- Engagement and motivation: The methods used take account of the need to engage and motivate participants and manuals specify how this will be done.

- Continuity of programs and services: The program is integrated with other aspects of service provision, for example, sentence planning or community supervision.

- Process evaluation and maintaining integrity: Provision is made for monitoring integrity of delivery, that is, to check that the sessions are being delivered in accordance with the planned model.

- Ongoing evaluation: Arrangements are in place for data collection and analysis, used in ongoing and outcome evaluation.

In order to receive accreditation, a program submitted to the CSAAP must be accompanied by a considerable quantity of supporting documentation that clarifies precisely what it contains and what is involved in its delivery. Each program should have five manuals: (a) a Theory Manual which describes the intervention model and evidence supporting it; (b) the Program Manual which specifies the content, exercises, and materials used in the sessions; (c) an Assessment and Evaluation Manual showing how the applicants are assessed, their progress is monitored, and outcomes evaluated; (d) a Management and Operational Manual prescribing aspects of delivery and organization; and (e) a Staff Training Manual. The program materials are evaluated and allotted a score on each of the 10 criteria listed above (such that a score of 2 = fully met, 1 = partially met, 0 = not met). A program must gain a total score of 18–20 points to be awarded accredited status. A history of the Panel’s work and an account of the challenges arising within it are given by Maguire et al. (2010). Similar arrangements involving expert panels or other validation procedures have been set up in Scotland, Canada, Sweden, and elsewhere.

Evaluation Of Outcomes

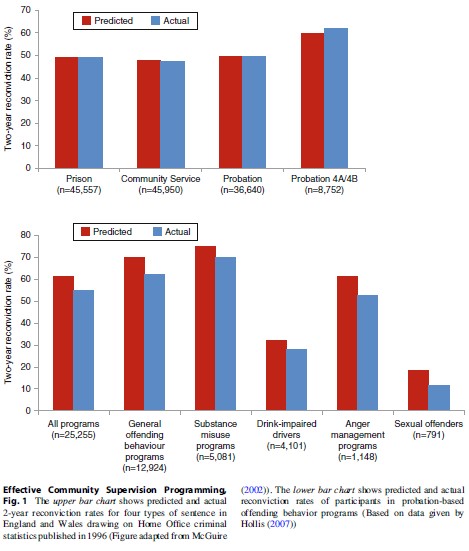

Can the introduction of structured programs within community supervision make a meaningful difference to its effectiveness? It is one thing to obtain a good result from an experimental trial, but another to capture the same result when interventions are “rolled out” across multiple, widely dispersed sites (the difference between what have been called “demonstration” as compared to “practical” programs). It may be useful to examine this first on a “before and after” basis by comparing two sets of results. Figure 1 compares four types of sentencing “disposals” available to the courts in England and Wales during the 1990s. In each case, the predicted rate of reconviction within 2 years is compared with the actual rate over the same timescale. The predictions were calculated using the Offender Group Reconviction Scale (OGRS-2), a specially designed instrument developed on the basis of multivariate analysis of criminal histories of large samples of offenders. This combined a series of seven pieces of data into a prediction score, the percentage of offenders likely to be reconvicted within 24 months. The OGRS (now in its third revised version, OGRS-3) has been validated as among the most accurate predictors in recent metaanalytic reviews of the field of criminal reconviction (see, e.g., Yang et al. 2010).

The four types of sentences compared in the upper graph of the figure are those which were the principal disposals available to the courts in the 1990s: respectively, they were immediate imprisonment, community service order, probation supervision, and probation with additional requirements. The data were originally compiled in order to compare the differential effectiveness of sentences, primarily the relative impact of custodial versus community sentences on recidivism. The value of these data lies in the side-by-side comparison of predicted with actual rates within each sentence type. As can be seen in each case, the figures are very close; the rates at which individuals were reconvicted were very similar to the rates at which they were probably going to re-offend, and that occurred regardless of the type of sentence imposed upon them. The sentence of the court appeared to have no obvious bearing on the outcome; indeed it seems virtually unrelated to it. Community sentences were neither any better nor any worse than prison sentences in terms of recidivism outcome. The relevance of this for present purposes, however, lies in the finding that there was no evidence that probation supervision had had a beneficial effect in reducing reconviction rates. Such a finding is not unique, but fits with other findings obtained from elsewhere. In a study in the Australian state of New South Wales, supervision as traditionally conceived was not found to have any greater effect on reconviction rates than a court bond involving no direct supervision of offenders (Weatherburn and Triboli 2008). In a large-scale review of the use of intensive supervision programs (ISPs), with a study sample of 1,812 offenders across nine American states, in which a primary emphasis was placed on the surveillance component, similarly no evidence of a beneficial impact was found (Petersilia and Turner 1993). In a meta-analysis of studies of community supervision conducted for Public Safety Canada, supervision alone was found to result in a reduction in recidivism of only 2 % points and effect size of zero for violent recidivism (Bonta et al. 2008).

Effective Community Supervision Programming, Fig. 1 The upper bar chart shows predicted and actual 2-year reconviction rates for four types of sentence in England and Wales drawing on Home Office criminal statistics published in 1996 (Figure adapted from McGuire (2002)). The lower bar chart shows predicted and actual reconviction rates of participants in probation-based offending behavior programs (Based on data given by Hollis (2007))

Effective Community Supervision Programming, Fig. 1 The upper bar chart shows predicted and actual 2-year reconviction rates for four types of sentence in England and Wales drawing on Home Office criminal statistics published in 1996 (Figure adapted from McGuire (2002)). The lower bar chart shows predicted and actual reconviction rates of participants in probation-based offending behavior programs (Based on data given by Hollis (2007))

The lower graph of Fig. 1 shows the findings of Hollis (2007) concerning the outcomes of probation sentences following the advent of structured programs. The sample size here is also quite large and the follow-up period is 2 years. Again, the predicted reconviction rates are based on use of the OGRS-2. Here the picture that emerges is different from that obtained as a result of sentences alone. For all offense types shown, for which specialized programs were available, there are significant reductions in actual as compared to predicted rates of reconviction. For program completers, the reductions were even larger: for general offending behavior programs, 26.4 %; for substance misuse programs, 19.9 %; for drink-impaired driver programs, 28.3 %; for anger management programs, 25.5 %; and for sex offender programs, 61 % (Hollis 2007). While this is not a controlled experimental trial, it nevertheless offers a striking contrast to the effects of the sanction of supervision alone. In their evaluation of ISPs, Petersilia and Turner also found evidence that “.. .higher levels of program participation were associated with a 10–20 % reduction in recidivism” (1993, p. 315).

Side-by-side comparisons of offending behavior program participants with others not allocated to them have produced positive results in community settings. A major obstacle to evaluation however is the very high attrition rate among those allocated to attend, at least during the initial years following their inception. Fortunately in England and Wales there was evidence of significant improvement in this respect as programs became more firmly embedded in services, and completion rates doubled over a 5-year period (National Probation Service 2007). Evaluations of the probation “Pathfinder” programs showed that those who completed them were significantly less likely to re-offend than the comparison sample not allocated to attend (Hollin et al. 2008). While the evaluations could not be based on randomized experimental trials, questions arose as to whether this might merely be a selection effect. However, further analysis showed that the observed effects could not be explained solely in terms of prior features of the participants (McGuire et al. 2008), discerning a difference that was most likely an effect of treatment.

Another aspect of evaluation, increasingly emphasized as governments have proclaimed the need for gradually tightening constraints on public expenditure, is the relative cost of policies and practices when set alongside each other. Regarding criminal justice programs, however, the accumulated evidence suggests that the majority represent a net return on investment. The conventional statistic used for economic evaluation, the benefit-cost ratio, emerges as positive for the great majority of programs, and for some it is impressively high (Aos et al. 2001).

Numerous studies have discovered superior benefit-cost ratios for community-based treatment of criminogenic risks and needs as compared with custodial sentences (McGuire 2012). Taking the United States as illustrative, for the fiscal year 2008, the annual per capita cost of imprisonment in a Bureau of Prisons facility was $25,894 and in a community correctional center $23,881. By contrast, the annual cost of supervision by a federal probation officer was $3,743 (U.S. Courts 2009). The differences between these figures indicates that, even allowing for increased costs of program delivery, there are adequate resources for larger numbers of offenders to be supervised in the community with program attendance as an ingredient of their sentences.

Nonprogrammatic Aspects

Results of these evaluations are nevertheless still weaker than those obtained in some “demonstration” studies. A possible explanation for this may reside not in the nature or effects of progams themselves, but in what have been called “nonprogrammatic” aspects of their implementation. This refers to a spectrum of issues including the use of well-validated assessment methods, appropriate allocation to programs and services, high-quality interactions between staff and participants, procedures for maintenance of program integrity, and provision of organizational support. There has been a consensus that these aspects of delivery and implementation have been neglected relative to the importance attached to programs themselves and that if insufficient attention is paid to them, especially when programs are diffused on a system-wide basis, integrity and consistency of delivery will be more difficult to maintain.

These areas have now been researched better, though given the intricacy and sometimes sensitivity of the issues to be explored, many questions remain unanswered. However, there is a steadily advancing grasp of the interconnections of program theory and design, on the one hand, and the factors that can optimize the chances of a program’s success (or militate against them), on the other. There is firm evidence that contextual and other aspects of service delivery have a close association with outcomes. Andrews (2011) has reviewed the available evidence on the importance of these features, and there are persuasive grounds for accepting that if key aspects of implementation are marginalized or ignored, this can undermine the prospective positive effects of program participation.

There is evidence, for example, that the use of structured learning procedures; higher levels of staff interpersonal skill; effective use of modeling and problem-solving approaches; establishment of positive relationships; and use of effective reinforcement, disapproval, and authority where appropriate are all significantly associated with the effectiveness of programs. With reference to the relational dimensions, some primary studies in this area suggest that a balanced combination of usage of authority with openness and interpersonal responsiveness generates better effects than either an autocratic, rule-oriented style or a highly sensitive, but overly permissive approach. Such a balanced supervisory style was associated with lower rates of recidivism in evaluation of the New Jersey Intensive Supervision Program (Paparozzi and Gendreau 2005). However, it seems unlikely that such an integrated supervisory style is extensively practiced by probation staff, though proposals have been forwarded as to how training can be provided to encompass it. Of particular note is the model of Strategic Training Initiative in Community Supervision (STICS), developed in Canada and designed to translate the findings of the “what works” research into skills training for community supervisors (Bourgon et al. 2010).

Several recent reviews have underlined the importance of appropriate assessment and allocation to programs by risk level, the safeguarding of program quality, and adherence to the prescribed treatment model. There is evidence that when risk levels, model fidelity, and other factors are taken into account, programs based in the community achieve larger effects than those provided in institutional settings. Equally important, a “treatment-oriented” philosophy invariably proves superior to a punitive ethos: interventions based on “human service principles” and with features of best practice in this respect yield consistently better outcome results than deterrence-based practices (Lowenkamp et al. 2010).

Implications And Extrapolations

There is a body of knowledge of steadily growing magnitude concerning the possibility of altering offenders’ lives, of enhancing community safety, and of reducing overall costs, through the provision of appropriate forms of intervention at the “tertiary” stage, that is, within criminal justice or correctional settings. Effective community supervision including structured programs focused on risk factors for offending has a sizeable role to play in bringing this about. One clear implication is for criminal justice or penal agencies to move away from a reliance on prison as the principal means of dealing with offenders. There are strong arguments instead for reserving it, as announced in so many promissory notes, to containing those who pose a serious threat to others or to themselves. Yet numerous datasets show that the prisons of many countries house large numbers of people who do not need to be there.

The continuing situation in which prison populations in some jurisdictions have swollen to unprecedented levels and resultant costs have spiraled, spent on a disposal route which evaluations continue to show is the least effective of the options available, is nothing short of remarkable. In the United Kingdom, carefully considered recommendations have been made by senior parliamentarians for a substantial reversal of the current trends and for a “reinvestment” in justice processes that have a more firmly anchored base in the community (House of Commons Justice Committee 2010). Evidence concerning the impact of programs should prove invaluable for any jurisdiction seeking to transfer resources and effort to reach a better balance of institutional and community-based provision. That holds, notwithstanding the sometimes weaker results of large-scale dissemination to date, which are almost certainly due to “failures of implementation” rather than to the contents or methods of programs in themselves (Andrews 2011). That is not of course to say that there is no room for improvement or no need to make further developments in the range of programs available. There are many questions still awaiting answers, and far more research is needed on these issues.

The concept of “justice reinvestment” can be interpreted broadly to provide a framework where the type of proposal being reviewed here can be incorporated as part of a wide portfolio of initiatives for transferring the burden of activity from custody to community. Allen (2011) suggests a series of seven possibilities, none of which would require any change in legislation: (a) increased use of diversion; (b) reduced use of remand, by providing alternative accommodation for homeless defendants; (c) making greater use of home curfew for others; (d) reducing the usage of short sentences which achieve very little in any case; (e) increasing the use of alternatives for those who breach community sentences; (f) reversing the steady decline in rates of parole; and (g) reducing rates of recall from parole. These can be set alongside and integrated with improvements in the delivery and content of probation and parole supervision. While as Kleiman (2011) suggests the latter has a dubious reputation in the eyes of many, based perhaps on the findings of Petersilia and Turner (1993), there are many more possibilities now in terms of what can be included within them. Unfortunately, in the past some had a track record of providing insufficient oversight, but Kleiman (2011) also describes far more efficient delivery and sanctioning strategies which can make a significant difference in these respects, illustrating this with reference to the very promising results of the HOPE (Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation with Enforcement) program which showed greatly reduced rates of missed appointments, positive drug tests, new arrests, and probation revocation in a 1-year randomized controlled trial (Hawken and Kleiman 2009).

Another possible model is that of the Intensive Alternatives to Custody (IAC) scheme piloted in England and Wales. This entailed a high level of probation contact over an initial three month period, reducing steadily over a further nine months. Though not yet fully evaluated, preliminary findings from a process study (Wong, O’Keeffe, Ellingworth and Senior 2012) and a one-year outcome study (Khan and Hansbury 2012) are encouraging. Those eligible included relatively prolific (an average of 29 previous convictions), substance-abusing offenders whose lifestyles would otherwise have been chaotic. The rate of non-compliance was very close to that found in standard probation supervision where 25 % of orders are terminated for negative reasons (failure to comply with requirements or conviction for a further offence). The rate of reconviction at 12 months was somewhat lower (56.1 % as against 63.6 %) than that of a matched group given custodial sentences. Note that even if the latter rates were exactly the same, the cost saving from the IAC is considerable relative to imprisonment, and participants are able to maintain contact with their families.

Key Issues And Controversies

To conclude, it should be acknowledged that the generally positive account regarding the use of programs reflected in this research paper is not universally shared. Programs have their critics and several reservations have been expressed concerning them. Some of the criticisms may be misplaced, for example, that programs are “not a panacea”: it is difficult to find a source in which a claim was made that they were. The more cogent criticisms focus on the model or vehicle of change seen as central to how programs work and to aspects of their delivery in everyday practice.

For example, it has been held that the key mechanism in engendering individual change is the nature of the link between an offender and the probation worker, what may be called (transposing terminology from elsewhere) the “therapeutic alliance.” But that had been the assumed vehicle of change in the numerous decades of probation work that preceded the advent of programs, and as described above there was a dearth of evidence concerning its impact. Furthermore, in the field of psychological therapy, while there is a consensus that a “working alliance” with the client may be a necessary condition of individual change, there is far less agreement concerning the extent of its importance or whether it amounts to a sufficient condition of change. Indeed based on systematic mining of the therapy process-outcome studies, even advocates for the importance of the alliance have conceded that it seems unlikely to account for more than 6–7 % of the variance in observed outcomes.

Possibly as a result of use of the word “treatment,” offender programs have sometimes been typified as representing a species of medical model, in which the offending individual is conceptualized as deficient in some respect that has to be remedied, a pejorative attribution. It is argued that the individual is viewed as a passive recipient of things that professionals “do to” him or her. This is however a straightforward misunderstanding of the learning theory model that informs most programs. A deficiency of skill or of the exercise of habits of self-regulation is a product of accumulated learning experiences (or the absence of opportunities for them). Efforts to address this have more in common with the spirit of the classroom than that of the clinic, and like education they work best when the individual is an active participant in the process.

It has also been argued that the pathway to desistance from offending represents a personal journey and has to be understood as a process rather than something that can be realized by participating in a structured program. There are claims to the effect that recognition of this constitutes a “new paradigm.” However, it is difficult to discern to what extent a proposal that involves a switch of emphasis can be held to constitute a new paradigm as such. There is nothing in the research literature on programs that conceptualizes individual change as an instantaneous event. Evidence on the changes that occur in individual offenders’ lives as they attempt to avoid reoffending is perfectly compatible with the models that underpin community programs, which require honest self-appraisal, focused thought, and repeated practice to produce results.

Finally, at least in England and Wales, several criticisms have flowed from the fact that the dissemination of programs was conducted on a larger scale and faster pace than initially expected. Those challenges were compounded by the fact that the policy agenda described earlier was pursued alongside several other far-reaching organizational changes in parallel. The unfortunate result that programs are perceived as simply serving the purposes of centrally led micromanagement, and part of the broader trend towards heightened “managerialism,” is in all likelihood a by-product of that process. There are however lessons that can be learned from this. Instigating too many changes simultaneously is a recipe for confusion and for damaging practitioner morale. The conjoined findings from programs themselves, and from the corpus of information now available on aspects of implementation, should ensure that efforts towards justice “reinvestment” can be more successful in future.

Further Reading

Edward J. Latessa and Paula Smith (2011) Corrections in the Community (5th edition, Cincinnati, OH: Anderson) is an excellent overview of the context and nature of work in this field and highlights some of the principal issues and controversies. For an overview of the background factors in theory and research that influence the design of programs and of outcome evidence regarding their effectiveness, see the book by Andrews and Bonta (2010), while for information on the rationale, contents, and outcomes of a range of specific types of program, see the volume edited by Hollin and Palmer (2006). The edited book by Joel A. Dvoskin, Jennifer L. Skeem, Ray W. Novaco, and Kevin S. Douglas (2012) Applying Social Science to Reduce Violent Offending (New York: Oxford University Press) challenges the current configuration of services in criminal justice and the overreliance on imprisonment, providing evidence-based and cogent arguments for a major change of policy. For a review of the “state of the science” in program implementation and evaluation, see the forthcoming book edited by Leam A. Craig, Louise Dixon, and Theresa A. Gannon, What Works in Offender Rehabilitation: An Evidenced-Based Approach to Assessment and Treatment (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell).

Bibliography:

- Allen R (2011) Justice reinvestment and the use of imprisonment: policy reflections from England and Wales. Criminol Public Policy 10:617–627

- Andrews DA (2011) The impact of nonprogrammatic factors on criminal-justice interventions. Legal Criminol Psychol 16:1–23

- Andrews DA, Bonta J (2010) The psychology of criminal conduct, 5th edn. Anderson Publishing, Cincinnati

- Antonowicz DH (2005) The reasoning and rehabilitation program: outcome evaluations with offenders. In: McMurran M, McGuire J (eds) Social problem solving and offending: evidence, evaluation and evolution. Wiley, Chichester, pp 163–181

- Aos S, Phipps P, Barnoski R, Lieb R (2001) The comparative costs and benefits of programs to reduce crime. Washington State Institute for Public Policy, Olympia

- Bonta J, Rugge T, Scott T, Bourgon G, Yessine AK (2008) Exploring the black box of community supervision. J Offender Rehabil 47:248–270

- Bourgon G, Bonta J, Rugge T, Scott T-L, Yessine AK (2010) The role of program design, implementation, and evaluation in evidence-based “real world” community supervision. Fed Probat 77:2–15

- Correctional Services Accreditation Panel (2010) Report 2009–2010. Ministry of Justice, Correctional Services Accreditation Panel Secretariat, London

- Craig LA, Dixon L, Gannon TA (eds) (2013) What works in offender rehabilitation: an evidenced-based approach to assessment and treatment. WileyBlackwell, Chichester

- Dvoskin JA, Skeem JL, Novaco RW, Douglas KS (2012) Applying social science to reduce violent offending. Oxford University Press, New York

- Gaes GG (1998) Correctional treatment. In: Tonry M (ed) The handbook of crime and punishment. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 712–738

- Gendreau P, Ross RR (1980) Effective correctional treatment: bibliotherapy for cynics. In: Ross RR, Gendreau P (eds) Effective correctional treatment. Butterworths, Toronto, pp 3–36

- Hawken A, Kleiman M (2009) Managing drug involved probationers with swift and certain sanctions: evaluating Hawaii’s HOPE. Office of Justice Programmes, National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

- Hollin CR, McGuire J, Hatcher RM, Bilby CAL, Hounsome J, Palmer EJ (2008) Cognitive skills offending behavior programs in the community: a reconviction analysis. Crim Just Behav 34:269–283

- Hollin CR, Palmer EJ (eds) (2006) Offending behaviour programmes: development, application, and controversies. Wiley, Chichester

- Hollis V (2007) Reconviction analysis of interim accredited programmes software (IAPS) data. Research Development Statistics, National Offender Management Service, London

- House of Commons Justice Committee (2010) Cutting crime: the case for justice reinvestment. First report for session 2009–2010. The Stationery Office, London

- Khan S, Hansbury S (2012) Initial analysis of the impact of the Intensive Alternatives to Custody pilots on re-offending rates. Research Summary 5/12. London: Ministry of Justice

- Kleiman MAR (2011) Justice reinvestment in community supervision. Criminol Public Policy 10:651–659

- Latessa EJ, Smith P (2011) Corrections in the community, 5th edn. Anderson Publishing, Cincinnati

- Lipsey MW, Landenberger NA, Wilson SJ (2007) Effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for criminal offenders. Campbell Syst Rev. doi:10.4073/csr.2007.6

- Lowenkamp CT, Flores AW, Holsinger AM, Makarios MD, Latessa EJ (2010) Intensive supervision programs: does program philosophy and the principles of effective intervention matter? J Crim Justice 38:368–375

- Maguire M, Grubin D, Lo¨ sel F, Raynor P (2010) ‘What works’ and the correctional services accreditation panel: taking stock from an insider perspective. Criminol Crim Justice 10:37–58

- McGuire J (2001) Defining correctional programs. In: Motiuk LL, Serin RC (eds) Compendium 2000 on effective correctional programming. Correctional Service Canada, Ottawa, pp 1–8

- McGuire J (2002) Criminal sanctions versus psychologically-based interventions with offenders: a comparative empirical analysis. Psychol Crime Law 8:183–208

- McGuire J (2005) The think first programme. In: McMurran M, McGuire J (eds) Social problem solving and offending: evidence, evaluation and evolution. Wiley, Chichester, pp 183–206

- McGuire J (2008) A review of effective interventions for reducing aggression and violence. Philos T Royal Soc B 363:2577–2597

- McGuire J (2012) Addressing system inertia to effect change. In: Dvoskin JA, Skeem JL, Novaco RW, Douglas KS (eds) Applying social science to reduce violent offending. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 265–290

- McGuire J (2013) “What Works” to reduce reoffending: 18 years on. In: Craig LA, Dixon L, Gannon TA (eds) What works in offender rehabilitation: an evidence based approach to assessment and treatment. WileyBlackwell, Chichester, pp 20–49

- McGuire J, Bilby CAL, Hatcher RM, Hollin CR, Hounsome JC, Palmer EJ (2008) Evaluation of structured cognitive-behavioural programs in reducing criminal recidivism. J Exp Criminol 4:21–40

- National Probation Service (2007) Annual report for accredited programmes 2006–2007. National Offender Management Service Interventions and Substance Abuse Unit, London

- Paparozzi MA, Gendreau P (2005) An intensive supervision program that worked: service delivery, professional orientation, and organizational supportiveness. Prison J 85:445–466

- Petersilia J, Turner S (1993) Intensive probation and parole. Crime Justice Rev Res 17:281–335

- US Courts (2009) Costs of imprisonment far exceed supervision costs. www.uscourts.gov/newsroom.2009/ costsOfImprisonment.cfm

- Weatherburn D, Triboli I (2008) Community supervision and rehabilitation: two studies of offenders on supervised bonds, Contemporary issues in crime and justice, number 112. New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Sydney

- Wong K, O’Keeffe C, Ellingworth D, Senior P (2012) Intensive Alternatives to Custody: Process evaluation of pilots in five areas. Ministry of Justice Research Series 12/12. London: Ministry of Justice

- Yang M, Wong SCP, Coid J (2010) The efficacy of violence prediction: a meta-analytic comparison of nine risk assessment tools. Psychol Bull 136:740–767

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.