This sample Effective Supervision Principles For Probation And Parole Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Overview

The content of parole and probation supervision, particularly in the United States, underwent an emphatic shift toward a focus on monitoring and surveillance starting in the mid-1970s. More recently, the field had focused increasingly on implementing supervision practices based on emerging evidence-based practices and the riskneed-responsivity model for changing offender behavior. However, changing everyday supervision practice to accommodate this emerging knowledge remains a challenge. Frameworks to translate this focus into concrete principles to guide the delivery of supervision have been created, but efforts to devise and test implementation models based on those principles are still in the early stages. Substantial questions remain about how to most effectively implement state of the art supervision practices at the agency level, what dosage and intensity of supervision is appropriate and effective for what types of supervisees, and what the effects will be of integrating new technologies into the practice of supervision.

This research paper reviews the organizational context within which probation and parole supervision is delivered, examines the recent history of the field, presents a summary analysis of effective supervision strategies, and explores several unresolved issues related to supervision. It addresses only the supervision functions of probation and parole, although there are many other important services provided by probation and parole agencies.

Scope And Role Of Probation And Parole

Probation and parole, referred to collectively as “community supervision,” are often confused in terms of responsibility and function. In most US states, probation supervises individuals who have received community supervision in addition to or in lieu of an incarceration sentence, while parole supervises offenders who have been released from prison, either through discretionary release by a parole board or mandatory release onto supervision. Some states and the federal government have abolished the traditional discretionary parole release function and have renamed the supervision function.

Both probation and parole represent a form of “conditional liberty” in which an offender is in the community under the supervision of a probation and parole officer (PPO). The offender is subject to “conditions” of supervision imposed by the court or releasing authority. The conditions are obligations (e.g., report to a PPO and pay victim restitution) or restrictions (e.g., do not possess weapons or leave the jurisdiction without permission) on the offender. The responsibilities of probation and parole agencies generally fall into three categories: intervention, surveillance, and enforcement. Intervention involves providing probationers and parolees with access to treatment and other services intended to bring about behavior change. Surveillance is the monitoring of the environment around and behavior of supervisees. Enforcement entails the PPO monitoring compliance with the conditions of supervision and sanctioning noncompliance. Failure to comply can result in revocation of the conditional liberty and a sentence to jail or prison.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world. However, incarcerated offenders represent only 30 % of the adults under correctional supervision in the United States according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics; the remaining 70 % are in the community under probation or parole supervision. This distribution has remained stable for more than three decades. One in 47 adults is on probation or parole. Probation is the most commonly imposed disposition for juvenile offenders, as well. Accurate national data on juvenile probation has only recently become available. The Census of Juvenile on Probation reports approximately 490,000 juveniles were on formal or informal probation in the United States in 2005.

The decentralized and fragmented nature of governmental structures in the United States makes it difficult to concisely describe the organizational context of probation and parole. Agencies at the federal, state, county, municipal, and tribal levels provide probation and parole supervision. There are private organizations that provide supervision as well, some nonprofit and others for profit. At each level of government, agencies are often split between the executive and judicial branches. Within a state, adult probation and parole may be combined in the department of corrections, while juvenile probation may be located at the county level within the courts. The possible combinations of branches and levels of government provide numerous possible configurations, most of which exist somewhere in the United States.

Despite carrying the majority of the correctional workload, probation and parole are not well understood by most elected officials, policy-makers, or the general public. This contributes to the chronically low funding levels for probation and parole and a general lack of political and public support. Probation and parole have also struggled with their mission over the past three decades, unable to articulate a compelling purpose and vision of public value created for the community.

Changing Currents In Parole And Probation Supervision

The history of the development of the mission of probation and parole supervision is critical to understanding the recent developments in terms of the principles of effective supervision and the challenges of implementing those principles. From their origins in the mid to late nineteenth century, both probation and parole were firmly based on the belief that with the proper guidance and assistance, offenders could be reformed while living in the community.

John Augustus, a Boston boot-maker, is credited with creating the modern concept of probation with his volunteer work in the Boston police court assisting both adults and juveniles that he deemed worthy of a second chance. In 1878, Massachusetts became the first state to authorize probation in statute. Other states followed and by the turn of the twentieth century, probation was an established component of the justice system (Latessa and Smith 2010). Zebulon Brockway, the superintendent of the Elmira, NY, reformatory, is credited with establishing the modern system of parole in 1877. As with probation, parole was designed to help reform inmates released from incarceration and was also firmly grounded on the rehabilitative principle. Parole also grew in popularity as the nineteenth century drew to a close and was soon also a common feature of the states’ correctional systems. The development of the nation’s first juvenile court in Cook County, IL, in 1899 signaled that juveniles were deserving of different treatment than adults, treatment that was overtly rehabilitative in nature. As a result, juvenile probation quickly developed in concert with the juvenile courts (Latessa and Smith 2010).

For the first century of probation and parole, rehabilitation was a core element of the mission and a prominent feature of practice. As the centennial of these institutions approached, things began to change. The firm commitment to offender treatment and rehabilitation was rolled back as the USA embraced a punitive, incarceration-driven response to crime. The end of the rehabilitative ideal came quickly, in large part due to the work of Robert Martinson, who published an article in the journal The Public Interest (1974), summarizing research on correctional treatment that he and two colleagues had conducted for the State of New York. While the results of the research have been debated extensively, the message that endured was that, in terms of treatment for offenders, “nothing works.” This triggered a wholesale retreat from treatment by institutional and community corrections agencies.

As a result, the philosophy and mission of probation and parole changed profoundly, from a balanced approach featuring assistance in combination with monitoring and enforcement to an approach that was predominately about watching offenders and returning them to custody when they violated the conditions of their supervision. Yet the idea that parole and probation should have a rehabilitative component never disappeared entirely. A similar dynamic occurred in the United Kingdom, where probation in England and Wales became very surveillance and monitoring oriented, while probation in Scotland remained within the social work tradition (Robinson and McNeill 2010). The National Research Council (2008, 36) summarized the resulting mission uncertainty for parole in this way (which could apply just as well for probation): “Variations in agency mission and culture—as well as in the fundamental role of parole itself—point to the conflict for parole agents: they don’t know whether they are expected to be law enforcement agents or social caseworkers. They have responsibility for enforcing the law and the conditions of parole, as well as assisting in released offenders’ reintegration in society.”

Over this period of mission uncertainty, the number of individuals that PPOs were responsible for supervising grew tremendously. From 1980 to 2009, a period that included the height of the “get tough” era and the war on drugs, the adult probation and parole population grew by 275 % according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. This tremendous increase in community supervision populations, and the caseloads of individual PPOs, further hastened a move away from activities intended to assist offenders, which are often very time-consuming. A greater role was assumed by tools that could quickly and accurately determine adherence to conditions of supervision, particularly drug testing and electronic monitoring.

At the same time, questions emerged regarding the effectiveness of community supervision as a strategy. Intensive supervision programs were found to be ineffective, meaning that “more” supervision did not produce better outcomes, although results were more promising for approaches that combined monitoring and appropriate treatment (Petersilia and Turner 1993). Analyses also showed that parolees subject to supervision had rearrest rates no better than similar people released from prison without supervision (Solomon et al. 2005). Findings like these raised serious questions regarding the value community supervision delivered, at least as commonly practiced in the United States at that time.

While the USA was moving away from rehabilitation to more punitive approaches, a small group of Canadian psychologists and correctional treatment staff was continuing to conduct and collect research on correctional treatment. From this research, largely produced subsequent to Martinson’s review, the Canadians found a growing number of programs that reduced recidivism, often by a substantial amount. In 1990, Don Andrews and his colleagues published an article based on this work that shifted the paradigm. Using meta-analysis, they introduced the principles of effective correctional treatment (Andrews et al. 1990). The first principles to be identified were the risk principle, the need principle and the responsivity principle. The risk principle stated that services should be directed toward high-risk offenders. The need principle stated that treatment should target criminogenic needs, those issues that lead to criminal behavior. The responsivity principle states that cognitivebehavioral treatment methods should be employed with offenders, and interventions should be tailored to the offender’s learning style, motivation, abilities, and strengths. Together, the risk, need, and responsivity principles are referred to as the RNR model, and adherence to the RNR model has consistently predicted intervention effectiveness in reducing re-offending (Andrews and Bonta 2007).

This new evidence supported the beliefs of many in the probation and parole field that Martinson’s conclusions were wrong, that offenders can change and that correctional staff can help make that change happen. The research, labelled “what works” in response to Martinson’s “nothing works”, reinvigorated the dialogue about the purpose and processes of probation and parole supervision. In the 1980s, when “risk control” was in vogue, probation and parole sought to punish and control offenders, using tools such as intensive supervision programs, day reporting centers and house arrest with electronic monitoring. With the rising use of actuarial risk assessments to predict likelihood of reoffense in the 1990s, “risk management” became popular. As the evidence continued to grow that treatment of offenders worked, the concept of “risk reduction” through offender behavior change came to the fore as people began to absorb the findings of the what works research.

While corrections was using the term what works to describe the use of empirically proven strategies and techniques, other fields such as medicine and education adopted the term evidence-based practices, or EBP, to describe their efforts at ensuring that clinical services and classroom practices reflected the latest research. With the publication of a series of papers on implementing evidence-based practices in community corrections by the National Institute of Corrections, the shift to EBP reached community corrections (Bogue et al. 2004). While a commitment to EBP in community supervision, at least at the rhetorical level, has become widespread (Jannetta et al. 2009), the contrasting supervision paradigm that allows supervising officers to carry large caseloads through reliance on drug testing and surveillance technologies that make violations easy to detect and substantiate persists in many agencies.

Content Of Effective Supervision

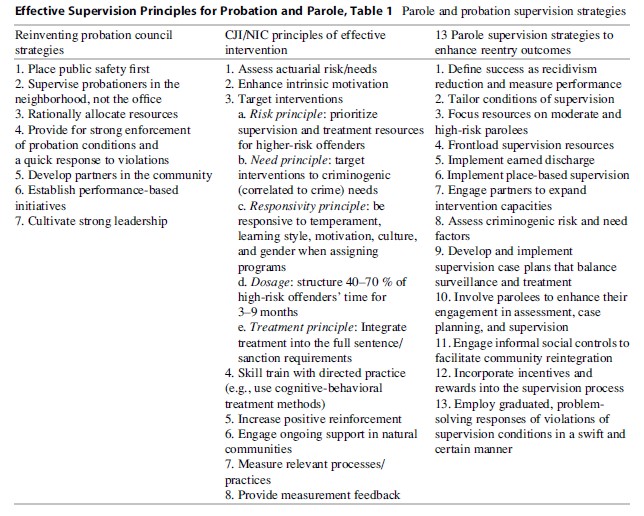

As the evidence basis for the effectiveness of correctional interventions grew, efforts began to enumerate general principles to guide the conduct of parole and probation supervision based upon the RNR framework and related research evidence on effective correctional interventions. These efforts were intended to present a package of mutually reinforcing strategies that would allow probation and parole to realize their potential to reduce re-offending. Principles defined by three prominent efforts are presented in Table 1. The first of was undertaken by the Reinventing Probation Council, a group of 13 veteran probation practitioners who met over 2 years to focus on “the systematic deficiencies of probation, and what strategies needed to be developed to revitalize probation” (Reinventing Probation Council 2000, 1). A similar effort to detail the ideal content of parole supervision was convened by the JEHT Foundation and the National Institute of Corrections in 2007 (Solomon et al. 2008). The Crime and Justice Institute (CJI) and the National Institute of Corrections put forth eight principles of effective intervention and detailed how they could be applied in community corrections (Bogue et al. 2004).

All three of these frameworks place reducing re-offending through changing offender behavior as the primary focus of community supervision efforts, in contrast to the narrower focus on surveillance and enforcement that had come to typify community supervision. By doing so, they attempt to resolve the mission confusion that has bedeviled parole and probation agencies at least since the decline of the rehabilitative ideal. Articulation of protection of public safety as a primary goal is common among community supervision agencies, but few have put in place robust accountability mechanisms around recidivism reduction. Performance measurement in community corrections is largely episodic, tending to focus on routine activities rather than outcomes.

Effective Supervision Principles for Probation and Parole, Table 1 Parole and probation supervision strategies

Effective Supervision Principles for Probation and Parole, Table 1 Parole and probation supervision strategies

The backbone of current approaches to facilitating risk reduction through community supervision is the use of actuarial risk/need assessment instruments to establish relative likelihood of re-offending and identify dynamic criminogenic needs to target for intervention. The use of assessment instruments including a broad range of dynamic items (i.e., those that can be changed) related to established criminogenic needs is now common, although not universal (Jannetta et al. 2009). Major criminogenic need factors include history of antisocial behavior, antisocial personality pattern, antisocial associates, family and/or marital factors, school and/or work factors, leisure and/or recreation factors, and substance abuse.

Results of these assessments guide community supervision at both the case and strategic levels. At the case level, assessment results should inform the development of a supervision plan, or case plan, detailing the goals and objectives that the supervisee must meet. Such plans are “the backbone of the supervision process, the map for how agents and offenders will identify and solve offenders’ problems” (Taxman et al. 2004, 31). These plans are a key method of ensuring that surveillance and treatment are combined as supervision techniques. This is crucial because a combination of surveillance and treatment is more effective at reducing recidivism than surveillance alone (Aos et al. 2006). It is also necessary to ensure that interventions facilitated by parole and probation target established criminogenic needs, because programs directed at non-criminogenic needs are ineffective. It is also important to embed assessment information in key tools of supervision, as the fact that assessments are conducted and the information is available to supervising officers is no guarantee that such information will actually be used in practice.

At the strategic level, assessment information is the foundation of the rational allocation of resources. In terms of persons, this means concentrating supervision and treatment resources on the people most likely to re-offend. Substantial allocation of resources is necessary to intervene with higher-risk offenders, because it is necessary to deliver high dosages of treatment, and to be prepared to address multiple criminogenic needs to improve their outcomes (Lowenkamp et al. 2006). It also steers intervention resources away from lower-risk offenders, whose outcomes can be worsened by intensive programming (Lowenkamp and Latessa 2004). The rational allocation of resources also refers to concentrating on the periods of time where the risk of failure is greatest, generally at the outset of the supervision period (National Research Council 2008). Additionally, allocation of resources includes initiating place-based supervision to focus on the locations in which risk factors for recidivism are more prevalent or simply where higher concentrations of supervisees are found.

Probation and parole supervision will have greater success in changing offender behavior if supervisees receive positive reinforcement. While many of the interventions needed to address criminogenic needs would likely require delivery by someone other than the supervising officer, enhancement of motivation and positive reinforcement can be delivered by the PPO. This includes providing incentives as well as utilizing techniques to enhance their motivation. Motivational interviewing, a technique to explore and resolve ambivalence about change and strengthen the motivation to change, has been widely adopted by correctional agencies, including community supervision agencies. Incentives should be more common than sanctions, with four positive reinforcements for every negative consequence (Taxman et al. 2004). Examples of incentives can include small things like bus tokens, certificates of achievement, or even verbal praise. More substantial incentives can include reduction of supervision reporting requirements and even discharge from supervision entirely. Involving parolees and probationers in developing their supervision and treatment plan is also a method for increasing their motivation to carry out the plan.

Working on enhancing motivation and supervisee buy-in to the goals of their plan requires attention to the responsivity component of the RNR model. Building a strong working relationship based on trust in the PPO to be firm but fair is an important element of effective supervision. It has long been established that elements of interaction between supervisees and supervising officers that are not programmatic in nature, such as officer decorum and interaction styles, have an important effect on offender outcomes (Palmer 1995). Behavioral management techniques, indicated by high levels of caring/ fairness and trust, are associated with success, and toughness-authoritarianism approaches are associated with failure (Skeem et al. 2007).

Greater collaboration with external partners is a prerequiste for effective supervision. External partners include agencies that can assist with the monitoring and intervention aspects of supervision work, such as law enforcement and community service providers. For people coming onto supervision after release from incarceration, greater coordination with institutional corrections allows for a more seamless transition approach that fosters positive change. Informal pro-social supports such as family members, employers, and neighbors are also important informal partners to engage. Relationships with these informal social supports are typically more effective than formal controls such as parole and probation supervision in promoting positive individual change (National Research Council 2008).

Finally, supervision violations must be responded to in a way that is swift, certain, and seeks to solve problems. Swiftness and certainty in sanctions are more important the severity of sanctions in deterring unwanted behavior, yet sporadic use of the most severe sanction, return to incarceration, has been the norm in supervision. The concept of graduated sanctions is now a firmly established approach to dealing with violations to ensure that every violation meets with some meaningful response, but that returns to custody are reserved for the most serious violations. Sanctioning guidelines or matrices the incorporate a graduated approach to responding to violations are now common in the supervision field (Jannetta et al. 2009) and have been shown to generate positive outcomes (Martin et al. 2009). There is also evidence that swift and certain delivery of short jail stays as a sanction can deter violations, provided supervisees are carefully targeted and warned ahead of time (Hawken and Kleiman 2009).

Models To Incorporate Effective Supervision In Daily Practice

The work over the last decade or so to identify and implement EBPs for supervision has been challenging. Several jurisdictions have successfully implemented the EBP model and have had their success documented by outside evaluators (Taxman 2008; Fabelo 2009). Many other agencies have implemented some effective practices (Jannetta et al. 2009). Despite the seemingly wide agreement that EBPs are the preferred way to go, there remains a persistent reluctance on the part of many in the field to fully embrace the model and commit to its full implementation. This reluctance stems from two major issues – lack of consensus on the mission of supervision and implementation challenges.

The residue of the “nothing works” doctrine can be found in many probation and parole agencies. An entire generation of staff has grown up professionally in organizations that were unwavering in their commitment to a law enforcement/surveillance model of supervision. The staff never experienced the balanced approach with rehabilitation of the pre-Martinson era. In many jurisdictions, the post-Martinson generation includes the agency leadership. Some leaders question the research, others have concerns about the viability of the model and still others wonder whether such an approach can be sold to local elected officials who have conservative views on crime and justice. For these and other reasons, they are reluctant to undertake EBP. The issue is whether the leadership of probation and parole agencies are willing to make the necessary commitment to transform their organizations. Absent a clear organizational commitment to a mission that is based on risk reduction through behavior change, there is little impetus to adopt EBP.

Successful organizational change, such as adoption of EBP for probation and parole supervision, requires an effective implementation effort. Good programs will not produce good results if they are not implemented properly. This includes ensuring fidelity to the all of the elements of the original program design. The issue is whether probation and parole agencies have (or can develop) the staff capacity and leadership capability to accomplish large-scale, long-term organizational change such EBP. Most executives and managers in probation and parole agencies have long experience and expertise with the substance of their agency’s core work; most do not have the experience with large-scale organizational development and change.

Fortunately, there are resources available to help. The National Institute of Corrections efforts in implementing EBP recognized this from the outset and subsequent efforts by NIC (Guevara et al. 2011) and the Council of State Governments Justice Center (Fabelo et al. 2011) have as well. Outside of the field of probation and parole, the National Implementation Research Network (NIRN) has been examining effective implementation strategies and techniques and offers assistance and resources.

Organizational commitment to the principles of effective supervision and EBP is not always sufficient to realign practice at the individual officer level. Even with training, officers may not base the supervision plan on the risk/need assessment and spend little time in meetings with supervisees addressing criminogenic needs (Bonta et al. 2008). Several operational models have been developed in an attempt to address this problem and ensure that supervision based on the principles of effective intervention is carried out consistently and with fidelity. There is some evidence that implementing such models can provide desired benefits even in the absence of fidelity, possibly by changing officer understanding of probationers and approach to violations that they incur (Harris et al. 2004).

Recent examples of operational approaches to supervision based on the principles of effective intervention indicate that they may be able to deliver both fidelity to the principles of effective supervision and improved outcomes. Implementation of Maryland’s Proactive Community Supervision (PCS) had an impact on the way PPOs did their case planning, and offenders supervised through PCS had fewer warrants filed for violations and were on supervision longer before failure (when it occurred) than did a matched comparison group of non-PCS-supervised parolees and probationers (Taxman 2008). Probation officers trained in Strategic Training Initiative in Community Supervision (STICS) spent significantly more time in sessions with probationers focusing on criminogenic needs and procriminal attitudes than did control officers. Probationers supervised by STICS probation officers had lower recidivism and reconviction rates after 2 years (Bonta et al. 2010).

Current Issues And Future Directions

Dosage: How Much Is Enough?

Since probation and parole became organized governmental functions, the question of optimal caseload size has been discussed. How many offenders can/should a PPO supervise? This is a straightforward, but very complex question that cannot be answered easily. Recent research has shown that smaller caseloads with EBP can produce improved outcomes (Jalbert et al. 2011). This is a critical finding because experience and research have shown that EBP-based supervision models take more time. More substantive interaction is required of each contact between PPO and offender and that takes more time than the traditional check-in only type of contact.

The EBP research suggests benchmarks for hours of correctional treatment of offenders by risk level, with higher-risk offenders receiving increased amounts of treatment or “dosage” (Bogue et al. 2004). Similar research is required to determine if there is a reliable metric that will suggest how much PPO time is required to be effective. Such inquiries should also explore whether there are optimal levels in terms of frequency of contact, length of contact and length of supervision. Such metrics would be invaluable in determining the optimal caseload size for different types of offenders and levels of supervision. These inquiries need to account for the content of supervision as well. Research on intensive supervision programs proved that devoting more PPO time to working with offenders, but on surveillance and monitoring activities, is not effective. Unpacking the dosage question will require attention to both the type of supervisee and the content of the supervision, changing the question to the more nuanced, “How much of what kind of supervision-based intervention do we need to deliver to what kind of person?”

Responding To Violations Of Conditions Of Supervision

One of the core elements of the original designs of both probation and parole was that there would be consequences for an offender’s failure to comply with the conditions of supervision. The challenge posed to probation and parole staff (and the judges and parole officials who must decide whether to revoke supervision) is that not all instances of noncompliance are equivalent. Violations of conditions vary in their seriousness, frequency, and legal status. Committing a new crime is a violation, as is failing to attend mandated treatment or missing a scheduled appointment with a PPO. The latter are known as “technical violations” as they do not represent criminal activity.

Responding to violations has been one of the weakest areas of probation and parole practice. Historically, PPOs have had but one tool in their kit, filing a violation of probation or parole and returning the offender to the court or paroling authority for a revocation hearing and potentially, a sentence of incarceration. Some PPOs were reluctant to file a violation for less serious infractions, often sending the message that such minor violation behavior would be tolerated. In the get tough era of the 1980s and 1990s, many agencies adopted “zero tolerance” policies for violations. These resulted in increased numbers of offenders being sent to prison for technical violations of probation or parole.

Finding effective responses to violations of probation and parole is important for several reasons. First, Bureau of Justice Statistics data shows that more than a third of the new admissions to state prisons in the USA consist of parole (primarily) and probation violators, many of whom have committed technical violations. Prison is a very expensive and harsh response that should be reserved for the most serious offenders. Research and experience has shown that many of these violators can be safely managed in the community at a much reduced cost. The second reason that alternatives to revocation are important has to do with the conventional wisdom among many in criminal justice, including probation and parole, that technical violations are a reliable precursor to criminal activity. Countless violations of probation or parole are filed as preventative measures, and thousands of offenders are sent to prison and jail. There is no reliable evidence to support this conventional wisdom, and recent research from Washington State found no reduction in new criminal activity from confining technical violators (Drake & Aos, 2012). Substantial research suggests that swift, certain and measured sanctions short of revocation appear to be effective with technical violations.

There is an operational (or political) challenge and a research challenge here. The operational challenge is to provide a robust set of options for responding to violations beyond doing nothing or returning to custody. Otherwise, there will be too much use of both. The research challenge is to illuminate the relationship, if any, between technical violations of various kinds and the criminal offenses that PPOs have traditionally revoked supervision in an attempt to prevent.

Integrating Desistance Theory

In its thorough review of the state of knowledge regarding parole, desistance from crime, and community integration, the National Research Council (2008) noted the importance of explaining gaps between research findings on what influences desistance and evaluation findings regarding program effects. Desistance theory has been minimally integrated into supervision interventions at this point in time, with supervision interventions mostly based on the theories of individual behavior change that underlie the RNR model. Longitudinal research on desistance highlights specific conditions that lead to less offending: particularly good and stable marriages and strong ties to work. These findings struck the National Research Council (2008, 2–3) as “somewhat at odds with findings from program evaluation that individual-level change, including shifts in cognitive thinking, education, and drug treatment, are likely to be more effective than programs that increase opportunities for work, reunite families, and provide housing.” Although the probation and parole field has long way to go to fully conform to the RNR model, exploring a next generation of supervision practice that more fully integrates the findings of desistance theory could further enhance the effectiveness of the field.

Technology-Based Supervision

How can technological approaches such as GPS help promote desistance? The evidence on the effects of electronic monitoring on supervisee success are mixed (Padgett et al. 2006; Finn and Muirhead-Steves 2002). GPS and other monitoring technologies, including minimal-level reporting mechanisms for low-risk offenders such as reporting kiosks and telephone reporting, are proliferating rapidly in the field. Location monitoring technologies such as GPS have the potential to increase the focus on monitoring and surveillance, as they make it possible to verify compliance with conditions such as curfews as easily as drug testing made it to verify compliance with conditions related to drug and alcohol use. How new supervision technologies could potentially support supervision to change offender behavior is unclear. Further investigation of what types of electronic monitoring and technology-based supervision approaches are effective (or not) for what types of supervisees is a crucial task for supervision researchers.

Conclusion

The emergence of the evidence base underlying the RNR model ended a period of great pessimism regarding the possibility that corrections agencies, including parole and probation agencies, could change offender behavior and thereby make communities safer. Although implementation of supervision practices conforming to the RNR model remains uneven at best, the field appears to have clarity regarding where it needs to go. While probation and parole continue to work on the organizational change necessary to do so, the research community can support them by better exploring the nuance of responsive supervision. What kinds of supervision work best for what kinds of offender, and at what dosage? What kinds of supervision violations need to be responded to in what way? Given the central role community supervision plays in the correctional system, aligning its practices with what is already known to be effective while continuing to build knowledge about effectiveness has the potential to make a huge contribution to public safety.

Bibliography:

- Andrews DA, Bonta J (2007) Risk-need-responsivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation. Public Safety Canada, Ottawa

- Andrews DA, Zinger A, Hoge RD, Bonta J, Gendreau P, Cullen FT (1990) Does correctional treatment work? A clinically relevant and psychologically informed meta-analysis. Criminology 28:369–404

- Aos S, Miller M, Drake E (2006) Evidence-based adult corrections programs: what works and what does Not. Washington State Institute for Public Policy, Olympia

- Bogue B, Campbell N, Carey M, Clawson E, Faust D, Florio K, Joplin L, Keiser G, Wasson B, Woodward W (2004) Implementing evidence-based practice in community corrections: the principles of effective intervention. National Institute of Corrections, Washington, DC

- Bonta J, Rugge T, Scott T, Bourgon G, Yessine AK (2008) Exploring the black box of community supervision. J Offender Rehabil 47:248–270

- Bonta J, Bourgon G, Rugge T, Scott T, Yessine AK, Gutierrez L, Li J (2010) The strategic training initiative in community supervision: risk-need-responsivity in the real world. Public Safety Canada, Ottawa

- Drake EK, Aos S (2012) Confinement for Technical Violations of Community Supervision: Is There an Effect on Felony Recidivism? Olympia, Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

- Fabelo T (2009) Probation evidence-based practices: a strategy for replication. Presentation to the Texas department of criminal justice judicial advisory council. Council of State Governments Justice Center, New York, justicereinvestment.org/files/TexasJudicialCouncilPresentation.pdf

- Fabelo T, Nagy G, Prins S (2011) A ten-step guide to transforming probation departments to reduce recidivism. Council of State Governments, New York

- Finn MA, Muirhead-Steves S (2002) The effectiveness of electronic monitoring with violent male parolees. Justice Q 19:293–312

- Guevara M, Loeffler-Cobia J, Rhyne C, Sachwald J (2011) Putting the pieces together: practical strategies for implementing evidence-based practices. National Institute of Corrections, Washington, DC

- Harris PM, Gingerich R, Whittaker TA (2004) The “effectiveness” of differential supervision. Crime Delinq 50:235–271

- Hawken A, Kleiman M (2009) Managing drug involved probationers with Swift and certain sanctions: evaluating Hawaii’s HOPE. Report submitted to the National Institute of Justice

- Jalbert S, Rhodes W, Kane M, Clawson E, Bogue B, Flygare C, King R, Guevara M (2011) A multi-site evaluation of reduced caseload size in an evidencebased practice setting. Abt Associates, Cambridge

- Jannetta J, Elderbroom B, Solomon A, Cahill M, Parthasarathy B, Burrell WD (2009) An evolving field: findings from the 2008 parole practices survey. Urban Institute, Washington, DC

- Latessa EJ, Smith P (2010) Community corrections, 4th edn. Matthew Bender & Co, New Providence

- Lowenkamp CT, Latessa EJ (2004) Understanding the risk principle: how and why correctional interventions can harm low-risk offenders. Topics in community corrections. National Institute of Corrections, Washington, DC

- Lowenkamp CT, Latessa EJ, Holsinger AM (2006) The risk principle in action: what have we learned from 13,676 offenders and 97 correctional programs? Crime Delinq 52:77–93

- Martin B, Van Dine S, Fialkoff D (2009) Ohio’s Progressive sanctions grid: promising findings on the benefits of structured responses. Perspectives 33:32–39

- Martinson R (1974) What works? Questions and answers about prison reform. Publ Interest 35:22–45

- National Research Council (2008) Parole, desistance from crime, and community integration. Committee on community supervision and desistance from crime. Committee on law and justice, division of behavioral and social sciences and education. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

- Padgett KG, Bales WD, Blomberg TG (2006) Under surveillance: an empirical test of the effectiveness and consequences of electronic monitoring. Criminol Public Policy 5:61–92

- Palmer T (1995) Programmatic and nonprogrammatic aspects of successful intervention: new directions for research. Crime Delinq 41:100–131

- Petersilia J, Turner S (1993) Evaluating intensive supervision probation/parole: results of a nationwide experiment. National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

- Reinventing Probation Council (2000) Transforming probation through leadership: the “broken windows” model. Manhattan Institute, New York

- Robinson G, McNeill F (2010) Probation in the United Kingdom. In: Herzog-Evans M (ed) Transnational criminology manual. Wolf Legal Publishers, Oisterwijk

- Skeem JL, Louden JE, Polaschek D, Camp J (2007) Assessing relationship quality in mandated community treatment: blending care with control. Psychol Assess 19:397–410

- Solomon AL, Kachnowski V, Bhati A (2005) Does parole work? Analyzing the impact of postprison supervision on rearrest outcomes. Urban Institute, Washington, DC

- Solomon AL, Osborne JWL, Winterfield L, Elderbroom B, Burke P, Stroker RP, Rhine EE, Burrell WD (2008) Putting public safety first: 13 parole supervision strategies to enhance reentry outcomes. Urban Institute, Washington, DC

- Taxman FS (2008) No illusions: offender and organizational change in Maryland’s proactive community supervision efforts. Criminol Public Policy 7:275–302

- Taxman FS, Shepardson ES, Byrne JM (2004) Tools of the trade: a guide to incorporating science into practice. National Institute of Corrections, Washington, DC

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.