This sample Fines In Europe Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Overview

Fine is the most used criminal sanction – both in history and in present. It is also one of the most neglected topics in textbooks and criminal policy analyses. The use of fines and other financial penalties has expanded during the last decades, as a result of several simultaneous changes. The growth of mass infractions in traffic and elsewhere has led to a differentiation of criminal fines into court-fines and summary fines (imposed either by the police or the prosecutor). Also the system of administrative monetary penalties has differentiated into fixed penalties for mass infractions and substantive penalties imposed for large-scale illegal economic activities and corporate fines.

Fines have several benefits which increase their potential as penal sanctions, also for middle rank offenses. This has been acknowledged especially by those jurisdictions that have adopted a day-fine (unit-fine) system. Under this system, the gravity of the offense is reflected in the number of imposed fine-units, while the monetary value of each unit is reflected by offenders’ financial means. Thus, two offenders, sentenced for similar offenses, receive fines that are experienced as equally severe, despite the differences in wealth and income. The available (albeit fairly meager) evidence suggests that fines are generally followed by somewhat lower reoffending rates compared to more substantive sanctions.

Not all fines are paid voluntarily, and a backup system for fines is required. The benefits of monetary penalties are lost, if unpaid fines need to be converted to imprisonment. Unfortunately, many jurisdictions have resorted to default imprisonment as a backup sanction. However, there are signs of a wider adoption of new community alternatives to serve this purpose.

History

In tribal societies, injuries were sanctioned either by vengeance or by settlement between the injurer and the injured. The Barbarian Codes (from the fifth century onwards) fixed the amount which can buy off vengeance. The victim (his/her relatives) had the option either to accept the offer or to resort on retribution. These sums cannot be defined as punishment in the modern sense, as there was no third authority to compel the parties to agree with the proposed compensation. It was only through the formation of state and central power that made it possible to establish a public criminal justice system where the ruler had the powers to dictate the sanctions for offenses. In Europe, this period starts around the middle of twelfth century (the establishment of “King’s Peace”). This was also the birth of fines as a criminal sanction.

Throughout the history, fines have retained a central position as criminal punishment. Fine was the principal punishment for most offenses in the Nordic codes, the earliest dating from mid-thirteenth century. The amount of fines was also fixed in detail according to the consequences of the acts, and in some cases also the mental state of the offender.

Still, the establishment of justice from above was a slow process. Private vengeance continued to be practiced throughout the later Middle Ages. In addition, fines, even after being authorized and confirmed by the state, served not only punitive but also private compensatory functions. This was also reflected on the way fines were divided in the Nordic codes into three parts: one third to the victim or his/her relatives, another to the King (central power), and one for the Church. Subsequently, punitive and compensatory elements were differentiated from each other, and fines became a matter of public criminal justice belonging to the central power alone. Alongside fines there grew a civil compensation to cover the damages and the losses of the victim.

European criminal codes grew gradually more punitive during the later Middle Ages. As a result, fines lost space to corporal punishments, especially in Central Europe and in England, where the administration of criminal justice came close to state-run terror in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. The eighteenth century witnessed the social and political revolutions across Europe, instigated and inspired by the writings of the enlightenment philosophers. Much of that criticism was a criticism against the brutality and severity of criminal justice of the ancient regime. The use of capital and corporal punishments was restricted and replaced by imprisonment, which came to form the backbone of the European criminal justice systems of the nineteenth century. But along with imprisonment, fines also retained a principal role as a basic sanction for minor and middle rank offenses, especially in the Nordic countries. Practical advantages of pecuniary penalties were recognized also by reformers like Montesquieu, who was among the first to recognize the need to grade the fines according to the financial situation of the offender.

Our fathers the Germans admitted almost none but pecuniary penalties. These men, who were both warriors and free, considered that their blood should be spilled only when they were armed. The Japanese, by contrast, reject these sort of penalties on the pretext that rich people would escape punishment, But do not rich people fear for the loss of their goods? Cannot pecuniary penalties be proportionate to fortunes? And, finally, cannot infamy be joined with these penalties?

Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws. Book VI, Chapter XVIII.

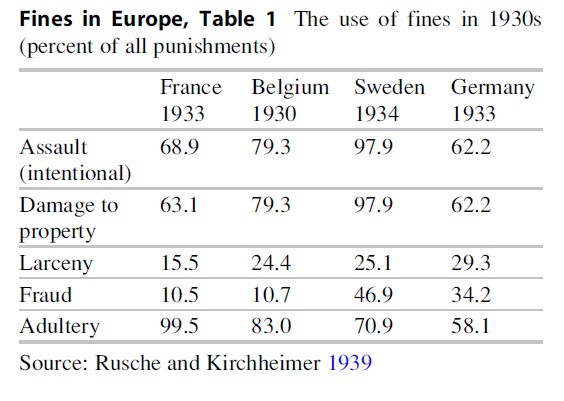

The practical use of fines was conditioned also by general economic conditions. According to Rusche and Kirchheimer (1939, p. 167), the poverty of lower classes remained as a central obstacle for the expansion of fines till the middle of the nineteenth century, whereafter their use has expanded, much caused by the decline of unemployment and the general rising of living standards. For example, in Finland and Sweden, over 90 % of cases dealt by the courts in the end of nineteenth century were punished by fines. Though often overlooked by historians and legal textbooks, fines remained the most used criminal sanction also during the twentieth century in several common offenses (see Table 1).

Fines in Europe, Table 1 The use of fines in 1930s (percent of all punishments)

Fines in Europe, Table 1 The use of fines in 1930s (percent of all punishments)

The System Of Financial Sanctions

Fines can be ordered by the courts or through simplified process by the prosecutor or the police. The expansion of mass-criminality in the form of new traffic offenses and the growth of petty property offenses (resulting from the change of opportunity structures) has led to an ever-widening adoption of summary proceedings. Today the majority of fines in most jurisdictions are imposed either by the police or the prosecutors.

Alongside “penal fines,” there are other kinds of financial sanctions with punitive and preventive functions, and which are sometimes hard to distinguish from penal fines. Continental legal theory makes a clear distinction between criminal and administrative sanctions. This distinction has also far-reaching consequences for the imposition and enforcement of sanctions. For example, administrative matters are dealt with by administrative courts and criminal matters in criminal courts. The use of criminal punishments is tied by much stricter legal safeguards and procedural guarantees, including requirements of guilt, presumption of innocence, and the principle of proportionality.

The growth of administrative sanctions alongside is based on two distinct reasons. Criminal law with all its legal safeguards has proven to be too expensive and heavy measure to deal with bagatelle-offenses. For reasons of procedural expediency, many countries have developed own administrative sanction systems to deal with traffic-offenses, minor infractions against public disorder, etc. The German system of “Ordnungswidrigkeit” has served as a model for several jurisdictions in the continental Europe.

On the other hand, criminal law has proven to be ineffective and impractical when it comes to dealing with large-scale economic activities where the magnitude of possible gains from illegal activities may be counted in millions. The establishment of corporate liability and corporate fine to control large-scale illegal economic activities may have been arranged either inside criminal punishment (with the requirement of criminal guilt) or outside criminal law (as an administrative sanction based on objective responsibility).

In addition to fines based on national corporate liability, there are an increasing number of economic sanctions based on the need to protect supranational market interests (EU fines). The EU Commission has set up guidelines on the method of setting fines imposed on firms which infringe European Union (EU) rules, prohibiting cartels and other restrictive business practices and abuses of dominant position (article 23(2) (a) of Regulation (EC) No 1/2003). The basic amount is calculated as a percentage of the value of the sales connected with the infringement, multiplied by the number of years the infringement has been taking place. Additional factors in setting the fine include the gravity of the infringement and possible previous infringements. The maximum fine for each firm remains 10 % of its total turnover in the preceding business year (Regulation EC No 1/2003, http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/competition/firms/l26118_en.htm). While traditional penal fines are counted in hundreds or occasionally even in thousands of Euros, EU-corporate fines are easily counted in millions.

In all, the present system of financial sanctions may be divided into three main groups (with considerable jurisdictional variations). (1) Fines defined as criminal punishments and imposed for natural persons, either by the courts or by other criminal justice agencies (prosecutors or the police). (2) Administrative penalties imposed for natural persons for mass infractions (parking tickets, etc.). (3) Substantial financial penalties/ fees imposed for illegal economic activities for natural persons or for companies (corporate fine), either under national or supranational (EU fines) rules. The following part of the paper discusses mainly about penal fines imposed for natural persons (group 1).

The Benefits Of Fines

The benefits of fines over other penal sanctions are generally known (see, for example, Gordon and Glaser 1991). Fines are generally less costly to administer and can provide revenue that, in some cases, exceeds their administrative costs. Secondly, monies paid to the court can be redirected to the victim of an offense in order to pay financial restitution for any physical or psychological harm incurred. Fines are a flexible penalty that can be adjusted to reflect both the severity of the crime and the offender’s financial circumstances (see below). Finally, the use of financial penalties avoids many of the debilitating social costs that are attached to incarceration (including the loss of job and leaving dependents with reduced income and labeling and making it more difficult for the offender to successfully return to the community). Fines permit the offender to remain in the community and in employment, and, in doing so, reduce the need for social support. Much of these benefits are dependent on the way the setting and enforcement of fines is arranged.

The Day-Fine System

Equal treatment of offenders requires that penalties for the same offense should be equally severe for different offenders. The same sum of money means different things for the rich and the poor, and it is an elementary requirement of social justice that people should be treated in the same manner despite the differences in wealth and economic resources.

Most fining systems have tried to meet the demands of equal impact by developing counting rules for balancing the differences in economic wealth. The Scandinavian day-fine system has proven to be the most successful in this respect. The day-fine system was adopted first in Finland in 1921, with Sweden and Denmark to follow in 1931 and 1939.

The origins of the system go back to the discussions in the International Association of Criminalists and their Nordic counterparts in the shift of the century, while the term day-fines was coined by a Swedish law professor Johan C.W. Thyre´n. The introduction of the day-fine system was motivated by three main reasons. Firstly, it provided a mechanism to ensure equal impact of sentence severity for the rich and the poor. Secondly, since the amount of fines was tied to the level of income, fines were more or less untouched by the changes in the value of money. And since this made it possible to maintain the level of fines high enough, fines could serve more effectively as alternatives for the much discredited short prison sentences. The Scandinavian day-fine system has served as an influential model for a number of European jurisdictions. During the last decades, countries such as Germany (1975), Austria (1975), France (1983), and Switzerland (2007) have adopted the system with success.

The main objective of the day-fine system is to ensure “equal severity” of the fine for offenders of different income and wealth. In this system, the number of day-fines is determined on the basis of the seriousness of the offense while the amount of a day-fine depends on the financial situation of the offender. The total sum of a fine is reached by multiplying the number of day-fines with their monetary value. The technical counting rules vary within each country, but the basic principle remains the same. It is also very much a matter of domestic penal (and social) policy whether income is counted before (brutto) or after (netto) taxes, and whether there exists a definite ceiling for the value of a single day-fine. In Finland, for example, the amount of the day-fine equals roughly half of the offender’s daily income after taxes (and without any upper limit; in Austria, the limit is 5,000 Euros and in Germany 30,000 Euros). The exact amount results from a rather complicated calculation. However, the officials (police, the prosecutor, and the courts) have in their hand a handbook which makes it easy to count the amount of dayfines. Also the number of day-fines varies in different systems: in Finland from 1 to 120, but in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland from 1 to 360.

An example from Finland: The typical number of day-fines for drunken driving with BAC of 1,0 o/oo would be around 40 df. The monetary value of one day-fine for a person who earns 1,500 euros/ months would be 20 euros. For someone with a monthly income of 6,000 euros, the amount of one day-fine would be 95. Thus the total fine for the same offense would be for the former person 800 euros and for the latter 3,800 euros.

Not all countries have followed this line. Most common law countries, including the USA, implement tariff fines, which leave much less – if any – room for the adjustment of fines according to the financial means of the offender. England and Wales adapted the system of “unitfines” based on the day-fine principle in 1991. However, after a heavy media-driven criticism, the government repelled the system in 1993. As noted by a leading legal commentator:

[T]o sweep away the whole edifice and to return to a system that promises, on the Governments own view, less fairness, fewer fines, and greater difficulty to enforcing them, .. . is eloquent testimony to the power of short-term political gain over sound penal policy. (Ashworth and Gibson 1994, Criminal Law Review 1994, 101 ff)

The failure of the unit-fines system in England and Wales in 1991 was basically a political one. It can be attributed mainly to the UK government’s inability to defend a sound system against ill-founded public pressure and misplaced criticism. As reported in surveys post the reform, courts that followed the unit-fines process were more consistent in their fining practice and they graduated the fines more proportionally according to the level of income. In short, their fine setting practice met the requirements of both equality and proportionality better, compared to courts that followed the old system (see Charman et al. 1996).

Despite the defeat in the UK, there have been ongoing efforts to expand the day-fine system in other common law countries. In the USA, this system has been renamed as “structured fines.” The first structured fine project demonstration in the United States was designed and operated by the Vera Institute of Justice in Staten Island, New York, between 1987 and 1989. Soon after, several other US jurisdictions had started to implement similar programs. But as it was also noted, these programs required well thought-out policy formulation and program planning, as well as a strong collection system. As the situation stands to days, a growing number of US jurisdictions are experimenting with structured fines (see Bureau of Justice Assistance 1996: How To Use Structured Fines (Day Fines) as an Intermediate Sanction, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/156242.pdf).

Institutional Requirements For Effective Enforcement

Effective enforcement of fines requires centralized and well-functioning enforcement organization. Fines need to be collected, which may sometimes need several consecutive acts by the state authorities and/or local municipalities. The authorities need to contact the debtor and, in case of nonpayment, enforce the payment, for example, by drafting a payment plan which allows payment by installments. The credibility of fining systems depends much on the effectiveness of this organization. Low payment rate undermines the credibility of the whole system. It reduces the public confidence of fining and it diminishes the willingness of the courts to use fines as sentencing options. The Nordic countries report fairly high collection rates (for example Sveri 2005, 376 reports that 90–95 % fines are paid in Sweden within 5 years). However, exact comparisons between different systems are complicated due to differences in counting methods.

As regards the day-fines system, key requirement for its effective implementation is that those responsible in setting the fines (whether the police, prosecutor, or the courts) have reliable information about the offenders’ income and financial situation. This can be ensured in several ways. In most Scandinavian countries, the criminal justice authorities (including the police) have access to previous year’s taxation files. More specifically, the police can receive on request last year total annual income via protected SMS data from the taxation officials. Should that option not be available, other sources for correct income data may be needed. In 1999, Finland criminalized giving false information of one’s income for the police in order to reduce the amount of fines. (However, after the establishment of the SMS link, the criminalization of “fine deception” became obsolete, with only two or three convictions per year).

Default Penalties

The credibility of fines as criminal sanction requires a backup system, which will be enforced in the case of nonpayment. The standard default sanction for unpaid fines has traditionally been imprisonment. In the course of history, default imprisonment has – from time to time – become one of the major causes for locking up people. In the 1930s, half of the males and two thirds of females were in English prisons due to unpaid fines (Rusche and Kirchheimer 1939, 169). In Finland, during the last prohibition years in the late 1920s, four out of five admitted prisoners were taken in custody because of unpaid fines.

If fines are converted to custodial sanctions, the original benefits of monetary penalties are lost. One may also end up using prison for trivial offenses, and for offenders whose major fault is that they are too poor to be able to pay their fines.

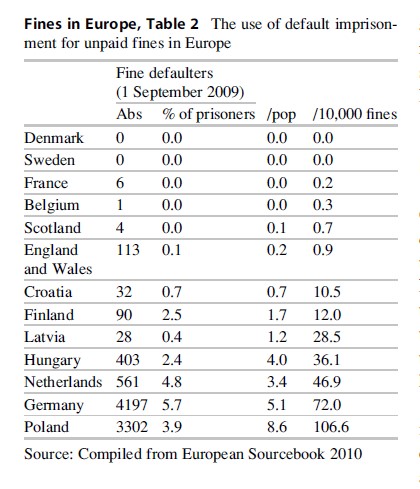

Fines in Europe, Table 2 The use of default imprisonment for unpaid fines in Europe

Fines in Europe, Table 2 The use of default imprisonment for unpaid fines in Europe

The discriminatory nature of default imprisonment has been acknowledged for long, and most countries have made efforts to restrict the use of default imprisonment, however, with different results. Some jurisdictions have adopted community alternatives as default penalties (such as supervised attendance orders in Scotland, community service in Germany, or the newly adopted “fine service” in Norway). Other countries have just simply ceased to impose default penalties for unpaid fines, as was done in Sweden in the 1980s. More recently also Denmark has practically ended the use of default imprisonment in the late 2000s. Finland, with probably the highest number of imposed fines in Europe, has also had the largest number of fine defaulters in the Nordic countries. However, in 2006–2009, the average number of fine defaulters in prisons (at any given day) has been reduced from around 200 to 50, removing all prosecutors’ fines outside the default system (Table 2).

As shown in comparative analyses, default imprisonment has practically disappeared in Denmark, Sweden, France, Belgium, and Scotland. In Poland, Germany, and the Netherlands, about 5 % of prisoners are in custody for unpaid fines. However, also in Germany, a considerable reduction of fine default imprisonment has been achieved by extending community service schemes in some federal states (see Dunkel 2004).

Fines In Practice

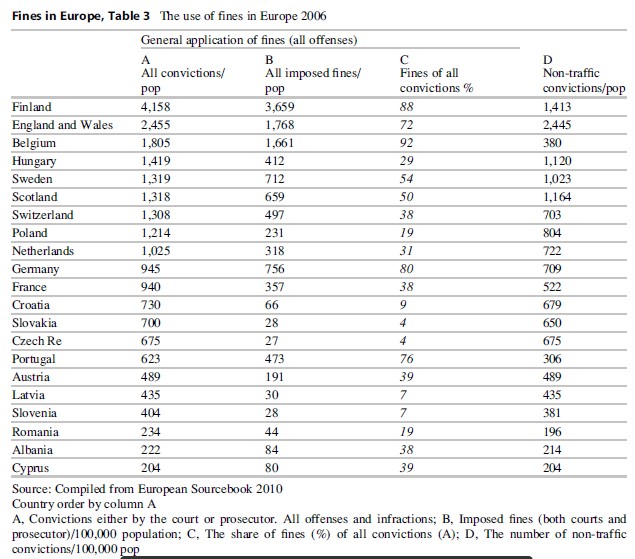

Criminal justice systems vary in their ways to deal with minor infractions. Some include even the most common traffic offenses (as is done in Finland) in criminal code, other exclude not only traffic offenses, but also many other minor infractions from their criminal justice statistics. With these caveats in mind, Table 3 makes effort to highlight the use of fines in European countries.

First column displays the number of all imposed sanctions (convictions) either by the court or prosecutor. All offenses and infractions are included. Comparison with column D (convictions excluding traffic cases) shows how much each nation’s criminal justice statistics are affected by traffic violations. Finland has the highest overall conviction rate (4,158), but three out of four convictions are for traffic cases (nontraffic convictions: 1,413). England and Wales, in turn, reports only non-traffic cases, as is done also by the Czech Republic, Latvia, and Cyprus. One must therefore look at the overall number of imposed fines (B) with caution. They reflect for some countries mainly traffic offenses, for others something else.

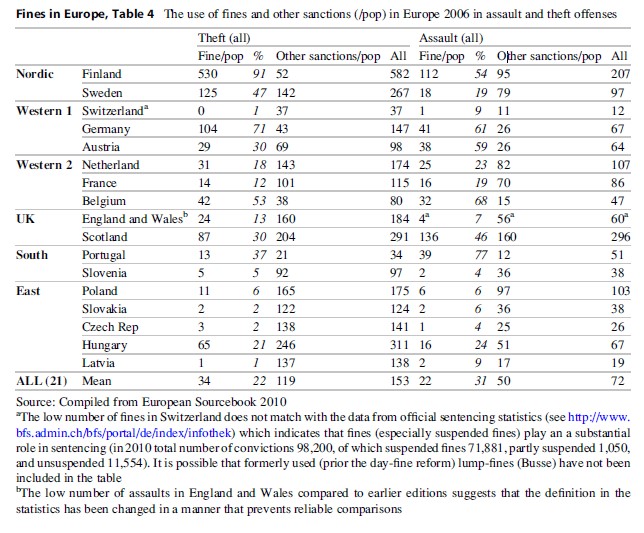

Some of these difficulties may be overcome, once the use of fines is analyzed separately for different offenses. Table 4 lists imposed fines and other sanctions/pop by countries and regions.

The average number of sanctions imposed for theft in 21 European nations was 153, of which 34 (22 %) were fines and 119 other types of penalties. For assault, the corresponding figures were 72 (all) 22/31 % (fines) and 50 (other sanctions).

The Nordic countries impose the largest number (300–600) of sanctions for theft offenses (together with Scotland and Hungary). However, in Finland, 9 out of 10 theft offenses are dealt with fines. This leaves around 52 other sanctions than fines imposed for theft in Finland, which, in turn, is considerably lower than the European average (119). Finland has the second highest number of convictions also in assault (207), after Scotland. More than half (112) of these are fines, which is five times the European average (22). This indicates that Finland imposes monetary sanctions for both offenses in a much larger scale than any other country (while the victimization rate for theft in Finland is well below the European average and for assault little above the average). The alternative explanation is that minor forms of property and assault offenses are in other countries dealt by sanctions that are not included in the European Sourcebook statistics.

Fines in Europe, Table 3 The use of fines in Europe 2006

Fines in Europe, Table 3 The use of fines in Europe 2006

There are marked differences between the countries and it is hard to discern clear patterns. However, with the exception of Hungary, fines are much rarer in the Eastern countries, while the overall level of imposed sanctions is fairly high in these countries, especially in theft offenses. Scotland imposes a large number of sanctions both for theft and assault offenses. Also fines are used in a high scale. Switzerland imposes a very low number of sanctions for both offenses, and uses practically no fines. Whether the use of fines is connected with the extent of imprisonment will be discussed next.

Fines As An Alternative To Imprisonment

Fines provide one alternative to short-term prison sentences. Finland has been, perhaps, more consistent with her efforts to expand the use of fines over other type of sanctions. After the adoption of day-fines in 1921, the next major reform took place in Finland in 1977 as a part of a general prison reduction program. The monetary value of day-fines was increased, thus making fines a more credible alternative for short-term prison sentences. As the follow-up studies show, this aim was largely achieved also in practice (Lappi-Sepp€al€a 2011). Similar results were gained also in Germany in connection with the replacement of short-term prison sentences (up to 6 months) by fines in 1969 and the adaption of the day-fine system in 1975 (see Dunkel and Morgenstern 2010).

Fines in Europe, Table 4 The use of fines and other sanctions (/pop) in Europe 2006 in assault and theft offenses

Fines in Europe, Table 4 The use of fines and other sanctions (/pop) in Europe 2006 in assault and theft offenses

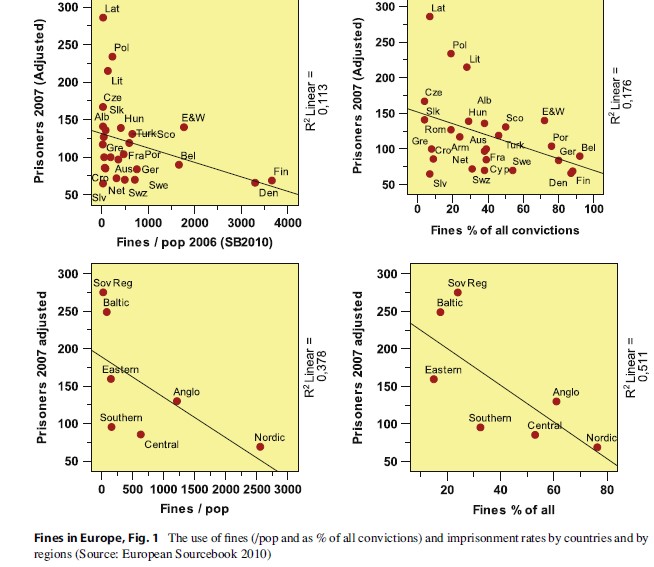

The association between the use of fines and national incarceration rates is examined in figure below (Fig. 1).

There is a clear inverse correlation with the overall use of fines relative to population, even though this correlation is much dominated by high rates from Finland and Denmark. The same applies to the share of fines and incarceration rates, with much more even distribution. Regional analyses reveal the exceptional position of the Nordic countries. They use much more frequently fines, and they have much lower incarceration rates. Eastern countries represent the other end of this scale with high incarceration rates and scarce use of fines.

Effectiveness

It is generally known that offenders receiving fines have the lowest recidivism rates. For example, in Finland, about 25 % of those receiving fines became reconvicted for some form of penalty during the following 5 years whereas the figure for those receiving prison sentence was as high as 75 %. But as the initial recidivism risk in these two groups is totally different, these figures cannot be used as a basis for comparisons. Unfortunately, there is fairly little systematic research with control groups on the effects of fines on recidivism.

Fines in Europe, Fig. 1 The use of fines (/pop and as % of all convictions) and imprisonment rates by countries and by regions (Source: European Sourcebook 2010)

Fines in Europe, Fig. 1 The use of fines (/pop and as % of all convictions) and imprisonment rates by countries and by regions (Source: European Sourcebook 2010)

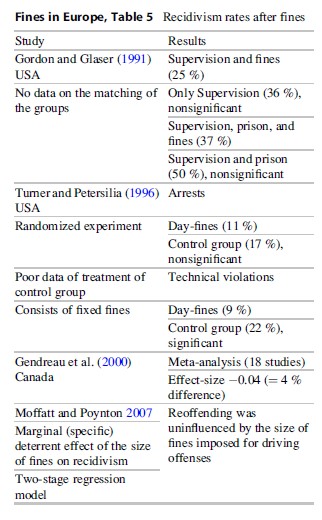

A study published in the USA in 1991 (Gordon and Glaser 1991) compared recidivism after different combinations of fines and other sanctions. Supervision with fines led to lower recidivism (25 %) than mere supervision (36 %). Equally short-term imprisonment with supervision and fines led to lower recidivism (37 %) than mere supervision and fines (50 %). However, the detected associations were statistically nonsignificant (Table 5).

A methodologically more advanced US study based on randomized experiment (Turner and Petersilia 1996) compared day-fines with flatrate fines (no difference according to income). It turned out that the day-fine group had a lower recidivism rate (11 % vs. 17 %) and less technical violations (9 % vs. 22 %) than the control group (latter differences were statistically significant).

The third study is a meta-analysis covering 18 studies (Gendreau et al. 2000). The overall effects size in these 18 studies was 0.04. In other words, after groups had been matched, those receiving fines showed a 4 % lower recidivism rate than those receiving other types of penalties.

The impact of the size of fines on reoffending was examined by a large-scale study carried out in Australia by the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, see Moffatt and Poynton (2007): 70,000 persons who received a court-imposed fine for a driving offense between 1998 and 2000 were followed for a period of 5 years to see whether they committed another driving offense. After controlling for a wide range of other factors likely to influence reoffending, a no relationship between the magnitude for the fine imposed and the likelihood of a further driving offense was found. The same negative result was obtained for drink-drive (PCA) offenses, drive while disqualified offenses, exceeding the speed limit and “other” driving offenses. The results are in line with the general findings that suggest that increased sentence severity does not go along with lower reoffending rates. However, the results leave the question of relative effectiveness of fines open.

Fines in Europe, Table 5 Recidivism rates after fines

Fines in Europe, Table 5 Recidivism rates after fines

Public Acceptance Of Day-Fines: A Case Study From Finland

Fines are vastly the most extensively used criminal sanction. At least one out of ten Nordic citizens receives each year either a fine or a corresponding administrative sanction, usually for a traffic violation. As pointed out by a Swedish professor in criminology:

There are many reasons why we should be more interested in the use of fine. We should never forget that more people are getting into contact with the legal system by being fined than by any other means. And because of this the way fines are handled by the representatives of the state will forever be remembered by the citizens. (Sveri 2005)

Smooth functioning of fining system is dependent on its legitimacy and public acceptance. Unfortunately, there is only limited research on the legitimacy and public perception of fines. The English government withdrew the unit-fine reform partly with reference to lack of public support – whether real or just printed in headlines. For this, the Finnish experience with another day-fine reform forms an interesting contrast.

In the shift of the millennium, the Finnish fining system received worldwide attention, thanks to extraordinary large traffic fines imposed for offenders with extraordinary high income. The Finnish law does not recognize any upper limit for a day-fine, and if the offenders’ annual income is counted in millions, the fines may well be counted in thousands of Euros – or even more.

The other source for criticism was the worry expressed by the conservatives that a system based on gross-income instead of net-income leads to unjustly severe fines in general in higher income levels. Under the conservative coalition government, gross-fining was changed to netfining in 1999 with the aim, “to introduce a more just fining system, whereby the size of the fine is perceived as fair among different income-groups” (Government Bill 74/1998).

A follow-up research was carried out in order to measure the degree of perceived fairness of the fining system. A total of 2,966 persons were interviewed at four different stages before and after the reform during the years 1999–2001. Key findings included the following (see Lappi-Sepp€al€a 2004):

- In general just below 60 % considered traffic fines generally to be fair, about one fifth considered them too low, and about one sixth too severe.

- Three out of four considered that the system with day-fines was in general fair.

- When asked whether speeding fines should be graded according to the drivers’ income, or whether the fine should be the same for all drivers, four out of five preferred differentiation according to income.

The assessments of fairness varied in different respondent groups. Not surprisingly, those who did not drive considered the system with dayfines to be fairer than those who drove (still, 70 % of drivers considered the system as fair). Men were more critical of the system with dayfines than women. Women would often be more apt to demand more severe traffic fines than men. As one could anticipate, respondents’ critical attitudes toward the day-fine system grew along with income-level.

Several of the findings were in clear contradiction with general presumptions about the public support of the fining system. Evidently the fears of the perceived unfairness of the fining system were grossly exaggerated. The reform of the fining system introduced in 1999 did not as such bring about any significant change in public opinion, once measured before and after the reform. Neither seemed the stirring fines imposed in summer 2000 appear to have affected the public’s confidence in the fining system for traffic offenses.

But as it also turned out, the general public was poorly aware of the rules concerning fines for traffic offenses. The fact, whether fines were counted on the basis on net-income or gross-income, turned out to be completely irrelevant for the perceived fairness of the fining system.

One major lesson was that the images of the public opinion, as expressed by the media and the politicians, may have very little to do with the views shared by the “silent majority.” Not surprisingly, the perceptions of fairness and the proper amount of control depended heavily on the respondents’ personal circumstances and financial situation: Those who do not drive wish more control and stiffer penalties, those who drive are less satisfied with the fining system, and those who have the highest income-level are the least satisfied with the day-fine system. Envy and self-interest are also essential elements in public opinion.

It seems that the legislators’ attempt to “gratify” the well-off offenders by moving from “gross-fining” to “net-fining” did not succeed.

Paradoxically, after the reform, the discontent of the fining system grew, especially among respondents in the highest income-level. In other words, those who benefited most from the new net-fining were the least satisfied with the changes brought by the reform. Either they had misperceived the content of the reform, or they were unhappy with the fact that giving false information to the police of their income had become a criminal offense (for the criminalization of fine deception, see above).

Surveys leave the door open for different interpretations. One fairly plausible conclusion could be that a clear majority of Finnish people consider the day-fine system and the fines imposed for traffic violations as reasonable fair and just. This was the case before and this was also the case after the reform (which, in fact, largely passed their attention). Another conclusion could be that the assumptions of the contents of “public opinion” may rest on a shaky basis – as may also lay the efforts to please this (assumed) general opinion.

Bibliography:

- Aebi M, Delgrande N (2012) Council of Europe annual penal statistics, SPACE I, survey 2010. Council of Europe, Strasbourg

- Aebi M, de Cavarlay BA, Barclay G et al (2010) The European sourcebook of crime and criminal justice statistics – 2010, 4th edn. Boom Juridische uitgevers, The Hague, Cited as Sourcebook 2010

- Ashworth A, Gibson B (1994) Altering the sentencing framework. Crim Law Rev February:101–109

- Bureau of Justice Assistance (1996) How to use structured fines (day fines) as an intermediate sanction. https:// www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/156242.pdf

- Charman E, Gibson B, Honess T, Morgan R (1996) Fine impositions and enforcement following the Criminal Justice Act 1993, vol 36, Home Office Research findings. Home Office, London

- Dunkel F (2004) Reducing the population of fine defaulters in prisons: experiences with community service in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (Germany). In: Council of Europe (ed) Crime policy in Europe. Good practices and promising examples. Council of Europe, Strasbourg, pp 127–138

- Dunkel F, Morgenstern C (2010) Deutschland. In: Dunkel F, Lappi-Sepp€al€a T, Morgenstern C, van ZyL Smit D (eds) Kriminalit€at, Kriminalpolitik, strafrechtliche Sanktionspraxis und Gefangenenraten im europ€aischen Vergleich, vol 1. Forum Verlag Godesberg, Mo¨ nchengladbach, pp 97–230

- Gendreau P, Goggin C, Cullen F, Andrews D (2000) Effects of community sanctions and incarceration on recidivism. Forum Correct Res 12(2):10–13

- Gordon MA, Glaser D (1991) The use and effects of financial penalties in municipal courts. Criminology 29:651–676

- Greene J (1988) Structuring criminal fines: making an “Intermediate Penalty” more useful and equitable. Justice Syst J 13:37–50

- Lappi-Sepp€al€a T (2004) Public perceptions and the fairness of the day-fine system. An evaluation of the 1999 day-fine reform. Tidskrift utgiven av Juridiska Fo¨ reningen i Finland 3-4/2004. pp 386–397

- Lappi-Sepp€al€a T (2011) Changes in penal policy in Finland. In: Kury H, Shea E (eds) Punitivity. International developments, vol 1, Punitiveness – a global phenomenon? Universit€atsverlag Dr. Brockmeyer, Bochum, pp 251–287

- Moffatt S, Poynton S (2007) The deterrent effect of higher fines on recidivism: driving offences. Crime and Justice. Bulletin NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research Contemporary Issues in Crime and Justice Number 106. March 2007. http://www.lawlink.nsw. gov.au/lawlink/bocsar/ll_bocsar.nsf/vwFiles/cjb106. pdf/$file/cjb106.pdf

- Rusche G, Kirchheimer O (1939) Punishment and social structure. Russel & Russel, New York

- Sveri K (2005) Incarceration for non-payment of fines. In: Bondeson U (ed) Crime and justice in Scandinavia. Forlaget Thomas, Kopenhagen pp 373–381

- Turner S, Petersilia J (1996) Evaluation of day fines in Maricopa county, Arizona, 1991–1993. RAND, Ann Arbor

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.