This sample Forensic Facial Analysis Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Overview

Closed-circuit television (CCTV) systems, digital cameras, webcams, and mobile devices are the source of a burgeoning number of facial images used in criminal investigations and prosecutions. Given the significance of facial identification to the courts – as well as to cases involving questioned identity documents and border control and immigration disputes – it is important that the strengths and weaknesses of methods used are properly understood.

Identification of an alleged offender is fundamental to the judicial process. Courts rely heavily on eyewitness evidence of identification, and they continue to do so where facial images are concerned. Evidence of identification, however, is widely acknowledged to be problematic. Procedures and processes intended to make identification more reliable – whether for use in investigation or in court – are perennial challenges.

Where facial image evidence is in issue, eyewitness evidence of investigators or other witnesses familiar with the suspect may be given. Alternatively, expert opinion of facial image analysis may be adduced. As well as being susceptible to the general weaknesses of eyewitness identification, the methods of facial image analysis are susceptible to biases known to affect other opinion evidence. The methods of facial image analysis are scientifically rudimentary and are as distinct from computational biometrics as they are from the other ideals of human identification: fingerprints and DNA.

Identification Of Offenders

It is almost self-evident that for a criminal prosecution to take place, an accusation must be made against a particular individual. The prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that the offense was committed and the accused committed it. Identification of the offender becomes a fact in issue when the accused denies they were the individual concerned. The onus is on the prosecution to prove it was.

Identification Of Repeat Offenders

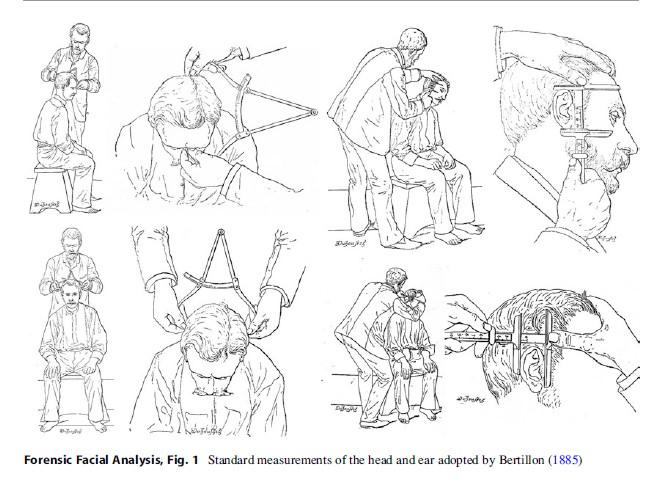

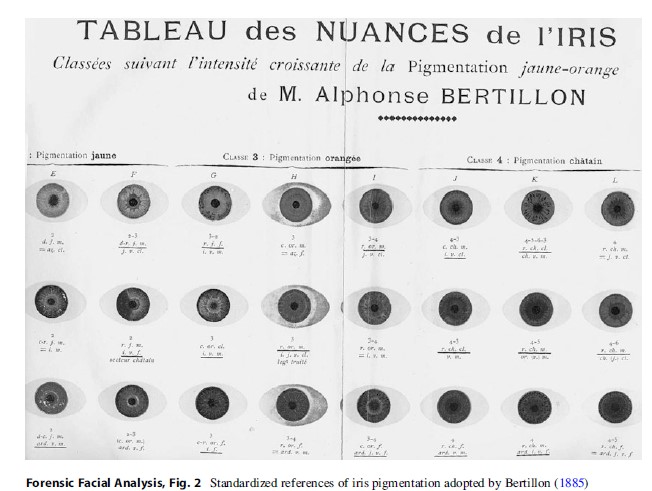

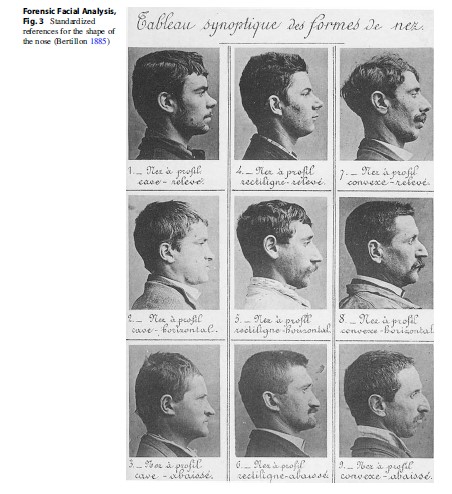

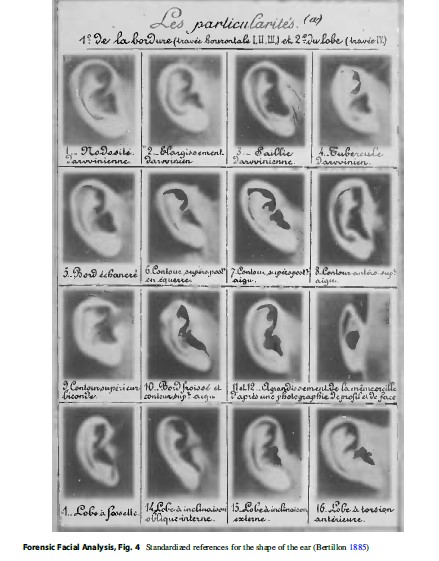

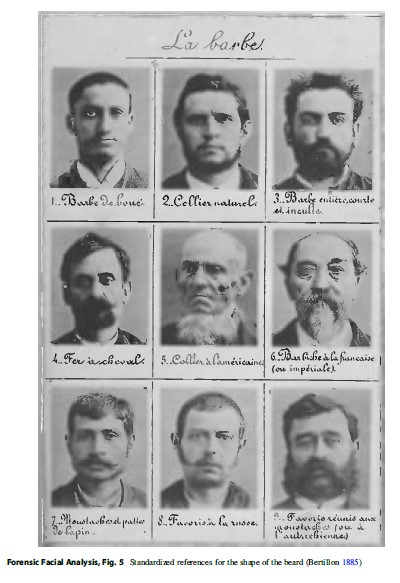

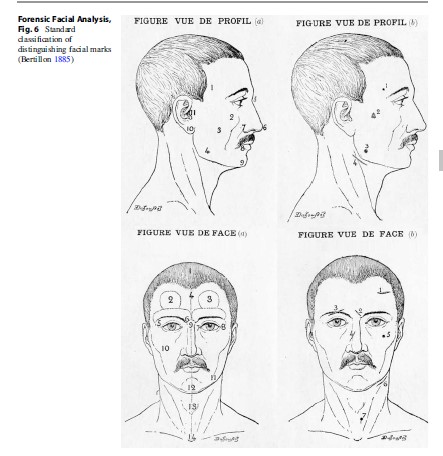

It is easy to suppose that before the advent of fingerprinting and forensic DNA profiling, the only evidence available to establish identity from physical appearance was eyewitness evidence, but this is not the case. In the late nineteenth century, Alphonse Bertillon (1853–1914) pioneered measurement of body shape – anthropometry – for the purposes of forensic human identification (Bertillon 1885). Bertillon was a pivotal figure in the development of forensic science, and facial comparison was a substantial component of his technique. The method – coined Bertillonage – involved measurement of a set of bodily dimensions, including those of the head and ear (Fig. 1). The method also incorporated classification of facial features, including the color of the iris (Fig. 2); the shape of the forehead, chin, and nose (Fig. 3); shape of the ear (Fig. 4); and style of hair and beard (Fig. 5). The nature and position of distinctive marks on the face were meticulously documented (Fig. 6) as part of a recording system which also established early standards for forensic photography.

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 1 Standard measurements of the head and ear adopted by Bertillon (1885)

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 1 Standard measurements of the head and ear adopted by Bertillon (1885)

Despite its widespread adoption, Bertillonage was abandoned in the early twentieth century in favor of dermatoglyphic fingerprinting. This method of human identification was faster, less error prone, required less equipment and training, and could be applied to marks left at a crime scene (Cole 2001).

Eyewitness Identification

If anthropometric measurement and systematic classification were discarded in favor of fingerprinting, then how are people identified from facial images and appearance in the criminal justice system?

Not surprisingly, individuals depicted in images are very often identified via eyewitness evidence of some kind. In the London Riots of 2011, for instance, many of suspects were recognized from CCTV footage. In these investigations, most suspects were identified by members of the public. Some police officers, however, are regarded by the Metropolitan Police as “super recognizers” on the basis of their ability to identify persons already known to them in CCTV footage using facial appearance and other cues. These apparent talents have been widely reported in the press (Grimston 2011; Jon 2009).

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 2 Standardized references of iris pigmentation adopted by Bertillon (1885)

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 2 Standardized references of iris pigmentation adopted by Bertillon (1885)

Forensic Facial Image Analysis

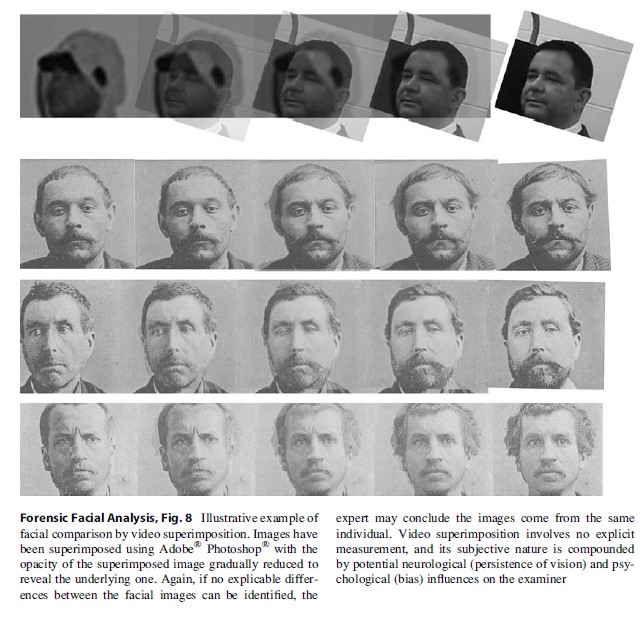

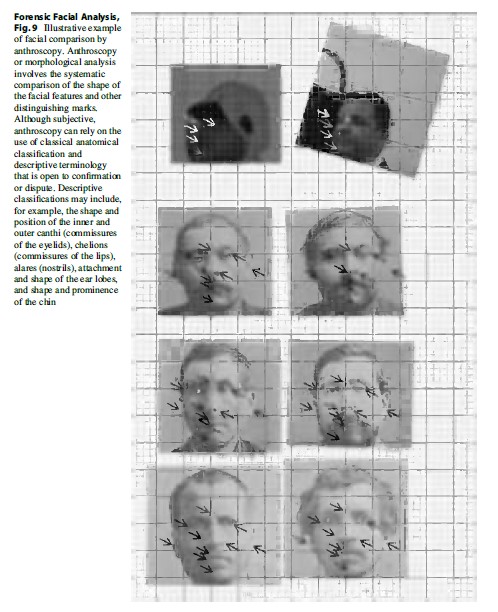

If eyewitness evidence is unavailable or inadequate, the methods of forensic facial image analysis may be applied. Three methods of facial image comparison are typically used in forensic investigation. They are photogrammetry or “facial mapping” (Fig. 7), image superimposition (Fig. 8), and anthroscopic or morphological analysis (Fig. 9).

Each of these methods requires an image of the offender – the questioned image – and a suspect image with the faces captured from the same or a very similar angle. The offender image may be obtained directly from digital closed-circuit television (CCTV), video or still cameras, cell phones, and similar devices. Offender images also continue to be extracted from legacy analogue videotape systems or scanned from photographs.

The offender image should ideally be the original. Alternatively, an unaltered copy can be used. There are a number of processes that have the potential to affect the fidelity of the copy, most notably digital image compression. Image compression may alter the image and may be “lossy,” leading to a forfeiture of information that cannot be restored. Lowering the resolution of images leads to pixilation of points and features rendering them difficult to identify, classify, and measure. Digital capture or scanning of analogue images also has the potential to alter them. For these reasons, uncompressed copies at the highest possible resolution are desirable.

Since the pose angle of the offender in the questioned image cannot be altered, some effort can be made to capture an image of the suspect at the same pose angle – sometimes using the original imaging system in situ at the scene. Precision is very difficult to achieve, however, and pose angles of offender and suspect rarely match exactly.

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 3 Standardized references for the shape of the nose (Bertillon 1885)

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 3 Standardized references for the shape of the nose (Bertillon 1885)

The systems used to capture offender and suspect images may also affect the precision that can be achieved in a comparative analysis. The processes of digital and analogue recording are different, and in either case lens distortion, focus, and lighting may affect offender and suspect images differently.

Working from a presumption of innocence, if inexplicable differences between offender and suspect images are identified, then the facial images are assumed to originate from two different individuals, and an “exclusion” can be made. Explicable differences may be attributed to factors such as pose angle, lighting, lens distortion, focus, image resolution, and compression discussed above or due to other factors such as facial expression, aging, trauma or surgery, hair style, and clothing and jewelry. These are sometimes referred to as the “confounding factors” of forensic facial comparison.

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 4 Standardized references for the shape of the ear (Bertillon 1885)

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 4 Standardized references for the shape of the ear (Bertillon 1885)

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 5 Standardized references for the shape of the beard (Bertillon 1885)

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 5 Standardized references for the shape of the beard (Bertillon 1885)

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 6 Standard classification of distinguishing facial marks (Bertillon 1885)

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 6 Standard classification of distinguishing facial marks (Bertillon 1885)

If no explicable differences can be found, further comparisons using one or more of the methods of forensic facial image analysis may be undertaken.

Facial mapping and image superimposition require that the images be rotated into alignment and adjusted to the same scale. Good practice dictates that it is the suspect image that is adjusted in order that the offender image is unaltered. Changing the proportions of the image invalidates the process of comparison, however, as one of its aims is to assess whether or not the two facial images share the same proportions. By implication, the scaling process would obscure any real difference in size between the heads of offender and suspect, should it occur.

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 7 Illustrative example of facial comparison by photogrammetry. Typically, a series of parallel lines are drawn between common features in offender and suspect images, such as the pupils, the commissure of the mouth, and the facial midline. If the lines are congruent and no explicable differences between the facial images can be identified, the expert may conclude the images come from the same individual or – more circumspectly – another individual of similar appearance

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 7 Illustrative example of facial comparison by photogrammetry. Typically, a series of parallel lines are drawn between common features in offender and suspect images, such as the pupils, the commissure of the mouth, and the facial midline. If the lines are congruent and no explicable differences between the facial images can be identified, the expert may conclude the images come from the same individual or – more circumspectly – another individual of similar appearance

Although “facial mapping” is known technically as photogrammetry, the implication that it involves detailed or complex mathematical analysis is misleading. The method simply consists of drawing parallel lines through points on features in the offender and suspect images, in order to compare their positions and the proportions of the face (Fig. 7).

Image superimposition involves the overlaying of offender and suspect images in order to perform a subjective assessment of similarity. The most common approach involves altering the visibility of the overlying image, gradually revealing the underlying one (Fig. 8). An alternative used in analogue systems is a “wipe,” in which the overlying image is sequentially cropped from one side to gradually reveal the underlying one. A further alternative is a “blink,” achieved by rapidly switching the overlying and underlying images. In each case, it is anticipated that the eye will detect subtle differences between the two images.

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 8 Illustrative example of facial comparison by video superimposition. Images have been superimposed using Adobe® Photoshop® with the opacity of the superimposed image gradually reduced to reveal the underlying one. Again, if no explicable differences between the facial images can be identified, the expert may conclude the images come from the same individual. Video superimposition involves no explicit measurement, and its subjective nature is compounded by potential neurological (persistence of vision) and psychological (bias) influences on the examiner

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 8 Illustrative example of facial comparison by video superimposition. Images have been superimposed using Adobe® Photoshop® with the opacity of the superimposed image gradually reduced to reveal the underlying one. Again, if no explicable differences between the facial images can be identified, the expert may conclude the images come from the same individual. Video superimposition involves no explicit measurement, and its subjective nature is compounded by potential neurological (persistence of vision) and psychological (bias) influences on the examiner

Morphological analysis or anthroscopy (Fig. 9) involves making a systematic assessment of the shape of the head, face, and facial features. Photographs or digital images can be used. A grid may be used to guide comparison.

Morphological analysis or anthroscopy (Fig. 9) involves making a systematic assessment of the shape of the head, face, and facial features. Photographs or digital images can be used. A grid may be used to guide comparison.

If – after facial image analysis – no explicable differences can be found, the images may be said to “match.” Normally, a further assessment is required to judge the extent to which the “match” supports the proposition that the faces in the offender and suspect images are from one and the same person.

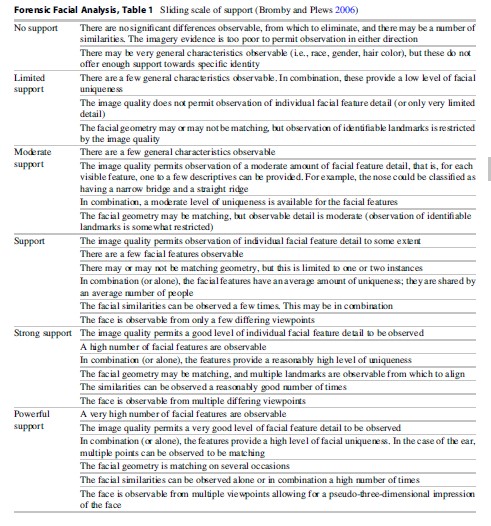

The UK Forensic Imagery Analysis Group (FIAG) advocates a sliding scale of support (Bromby and Plews 2006), with criteria for assignment to each level on the scale (Table 1). The court is usually provided with a statement describing the analysis and the expert’s view as to the strength of support it affords for the assertion that the facial images depicted are from the same individual. Recently, experts have qualified their opinion by stating matching evidence may arise from the defendant or someone of similar appearance.

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 9 Illustrative example of facial comparison by anthroscopy. Anthroscopy or morphological analysis involves the systematic comparison of the shape of the facial features and other distinguishing marks. Although subjective, anthroscopy can rely on the use of classical anatomical classification and descriptive terminology that is open to confirmation or dispute. Descriptive classifications may include, for example, the shape and position of the inner and outer canthi (commissures of the eyelids), chelions (commissures of the lips), alares (nostrils), attachment and shape of the ear lobes, and shape and prominence of the chin

Bertillon (1885) appears to have perceived this issue. Distinguishing dissimilar faces is frequently trivial. Distinguishing similar faces is the real problem. Other than the author’s own image, the faces given in the examples in Figs. 7, 8 and 9 are those Bertillon chose to illustrate the problem of distinguishing similar faces. In two of the three examples, the images originate from the same individual, in one exceptional example they do not.

Forensic Facial Analysis, Table 1 Sliding scale of support (Bromby and Plews 2006)

Forensic Facial Analysis, Table 1 Sliding scale of support (Bromby and Plews 2006)

Current Issues And Controversies

Facial image analysis remains a subjective process sometimes supported by a technical method and then only in part. Psychological studies have raised issues concerning the reliability of face recognition and of cognitive bias in comparative forensic analyses. Reviews of the effectiveness of forensic science have questioned the scientific basis of many forensic science subdisciplines as well as the subjective paradigm from which the forensic identification sciences operate.

The Psychology Of Face Recognition

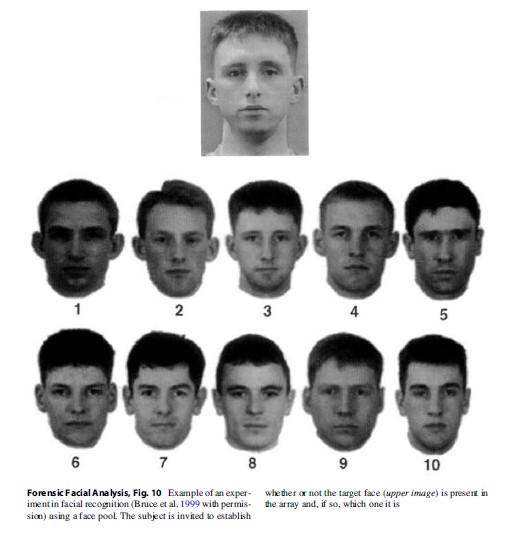

While face perception and face recognition remain exciting subjects of academic inquiry, certain features of our ability to perceive and recognize faces are clear. People are very good at recognizing familiar faces and very bad at recognizing unfamiliar ones. Using standardized sets of photographic images called face pools (Fig. 10), researchers in psychology (Bruce et al. 1999) demonstrated the highly error-prone nature of recognition of unfamiliar faces. Kemp et al. (1997), for example, attached small photographs of shoppers to credit cards and asked cashiers to confirm that they belonged to the bearer. The subjects were able to detect fraudulent cards in only 36 % of trails when the photograph bore some resemblance to the bearer and in 66 % of trails when the photograph bore no resemblance.

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 10 Example of an experiment in facial recognition (Bruce et al. 1999 with permission) using a face pool. The subject is invited to establish whether or not the target face (upper image) is present in the array and, if so, which one it is

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 10 Example of an experiment in facial recognition (Bruce et al. 1999 with permission) using a face pool. The subject is invited to establish whether or not the target face (upper image) is present in the array and, if so, which one it is

Familiar faces are, in contrast, reliably recognized from face pools.

The same pattern is evident when reliability is assessed using CCTV footage of familiar and unfamiliar subjects. Burton et al. (1999) showed familiar individuals can be recognized quite reliably even from poor quality CCTV footage, but unfamiliar subjects are frequently misidentified. The performance of students and police officers was similarly poor. Bruce et al. (1999, 2001) also demonstrated the highly error-prone nature of recognition of unfamiliar faces from CCTV images and video stream.

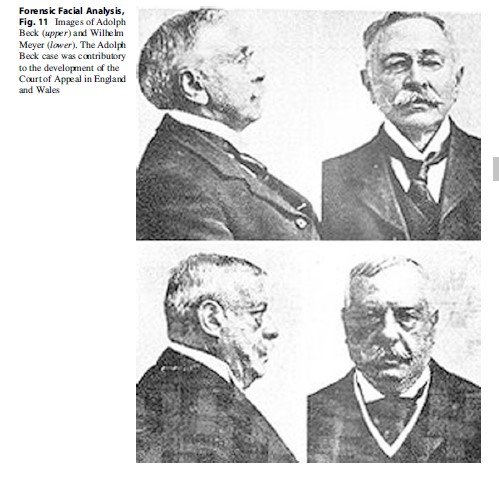

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 11 Images of Adolph Beck (upper) and Wilhelm Meyer (lower). The Adolph Beck case was contributory to the development of the Court of Appeal in England and Wales

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 11 Images of Adolph Beck (upper) and Wilhelm Meyer (lower). The Adolph Beck case was contributory to the development of the Court of Appeal in England and Wales

Error In Eyewitness Identification

The findings of Bruce and other psychologists of face perception offer scientific confirmation of the potential danger of eyewitness identification long recognized by the courts. Cases of mistaken identity – particularly of individuals unfamiliar to the witness – have become seminal in reforms of judicial procedure. In England and Wales, the Turnbull guidelines – arising from R v. Turnbull 1977 (QB224 CA) – govern the circumstances and nature of warnings to the jury of the risks inherent in eyewitness identification. Similar procedures are followed in US courts – see Watkins v. Soders 1981 (449 US 341; 101 SCt 654).

Both psychologists and the courts accept that eyewitness identification can be dangerous when unfamiliar faces are involved. Psychological evidence indicates that recognition of familiar faces is quite reliable, but it certainly is not perfect. A celebrated English case from the nineteenth century involves that of Adolf Beck (Anon 1999), a man who had the misfortune to resemble fraudster Wilhelm Meyer, who presented himself to his victims as Lord Willoughby. One of Meyer’s victims mistook Beck for Meyer. Beck’s misfortune was compounded when ten or 11 of Meyer’s other victims also did so. Two police officers familiar with Meyer also identified Beck as Meyer. One, Ellis Spurrell, stated “There is no doubt whatever he is the man. I know what’s at stake on my answer, and I say without doubt he’s the man.” Having been found guilty not once, but twice of crimes committed by Meyer, Beck was awaiting sentencing when Meyer himself was arrested. The mistaken identity – and the passing resemblance of the two protagonists (Fig. 11) – finally came to light, and Beck was pardoned.

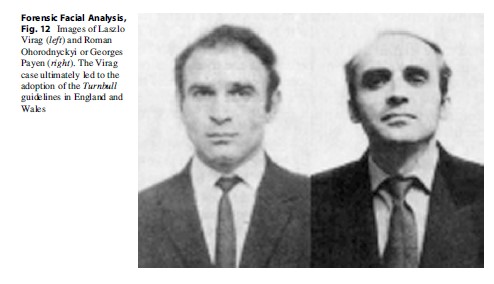

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 12 Images of Laszlo Virag (left) and Roman Ohorodnyckyi or Georges Payen (right). The Virag case ultimately led to the adoption of the Turnbull guidelines in England and Wales

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 12 Images of Laszlo Virag (left) and Roman Ohorodnyckyi or Georges Payen (right). The Virag case ultimately led to the adoption of the Turnbull guidelines in England and Wales

A further case arose in England in the twentieth century, which involved the mistaken identity of Laszlo Virag as armed thief Roman Ohorodnyckyi – also known as Georges Payen (Fig. 12). In the Virag case (Devlin 1976), a number of witnesses including police officers again mistook Virag for Payen and confidently so. One officer, Police Constable Smith, stated “his face is imprinted on my brain.” Virag was convicted, but items subsequently found in Payen’s possession, including the relevant firearm, led to Virag’s exoneration, the Devlin Report (1976) on identification in criminal cases, and the adoption of the Turnbulls guidelines.

Cognitive Bias

The findings of Bruce and other psychologists of face perception offer scientific corroboration for the premise that humans are good at recognizing familiar faces but poor at recognizing unfamiliar ones. Other psychological studies support the proposition that some individuals are exceptionally good at face recognition (Russell et al. 2009). Humans are, unfortunately, susceptible to other cognitive biases that can lead witnesses, including police officers, to mistakenly – if honestly – make highly confident, but erroneous identifications from facial appearance.

The wrongful convictions of Adolph Beck and Laszlo Virag each led to changes in the English court system and – in order to prevent errors and preempt courtroom challenges – to changes in police procedures relating to identification from arrest photographs and identification parades.

The risks of context and confirmation bias in forensic comparisons have been well rehearsed by Dror (Dror et al. 2006) in relation to fingerprints, and similar dangers apply to identifications from CCTV and forensic facial images. Video superimposition is a particularly subjective technique, with the capacity to obscure differences rather than reveal them.

Scientific Basis Of Forensic Facial Image Analysis

Forensic facial image analysis is scientifically rudimentary. There is a small literature (Porter and Doran 2000; Vanezis and Brierley 1996; Vanezis et al. 1996; Yoshino et al. 2000) supported by guidelines published in the USA (SWGIT 2012) and UK (ACPO 2009). Validation studies are almost unknown. There is no reported error rate for forensic facial image comparison, whether conducted by police “super recognizers” or “facial mapping experts.” There is no scientific basis for assigning the weight of a comparison against a sliding scale of support. This is a matter of subjective opinion. Two experts could disagree, and both be “right” – see Mallett and Evison (2013). This is a position that is hardly tenable in science. The limited scientific basis of forensic facial image analysis is discussed in further detail by Edmond (Edmond 2011) in relation to courtroom admissibility of facial comparison evidence. The UK Court of Appeal held in R v. T (ECWA Crim 2439; 2010) with regard to footwear impressions that the expert should not use the word “scientific” where it gives an impression to the jury of a degree of precision and objectivity that is not present. This caution is equally warranted with regard to facial image comparison and is all the more important giving the compelling nature of facial image evidence.

Conclusions And Future Research

Despite the ubiquity of the face as the primary mode of recognition in humans and the increasing prevalence of facial images, most forensic identifications are based on eyewitness evidence of some form. Forensic facial comparison is not scientific, and the scientific claims of facial mapping and image superimposition are tenuous. There are presently two significant drivers of potential change, however, that may lead to the development of a forensic science of facial image analysis. These are the systematic investigation of images from CCTV footage and the expectation for increasing scientific rigor in the forensic sciences.

Systematic Use Of Images In Criminal Investigation

The investigation of the London Riots of 2011 is notable for the extensive implementation of a thorough and systematic approach to the investigation of images from CCTV and other sources – digital cameras and other mobile devices. This approach was based on preexisting Visual Images Identification and Detection Office (VIIDO) units introduced by Michael Neville of London’s Metropolitan Police Service (Grimston 2011). Not only do these units control collection and analysis of image evidence, they ensure that it is supervised and actioned (Jon 2009). Online and mobile (APCO 2012) apps are offered to support dissemination of images captured from CCTV and other sources.

The Paradigm Shift In Forensic Science

The unparalleled success and reliability of forensic DNA profiling has led to a postulated “paradigm shift” in forensic science (Saks and Koehler 2005), which predicts that more of the forensic science subdisciplines will need to follow the model offered by DNA. Both the United States National Research Council (2009) and the UK Forensic Science Regulator (Rennison 2008) call for forensic science to be based on sound scientific methodology, logical and statistically supported interpretation methods, and known error rates. Biometric technology may offer some value to forensic facial comparison, but at present the value of automated systems is investigative and not probative (Dessimoz and Champod 2007; Evison 2011). Reliance on automated biometric systems may also lead to a new kind of complacency that promotes context bias (Dror and Mnookin 2010).

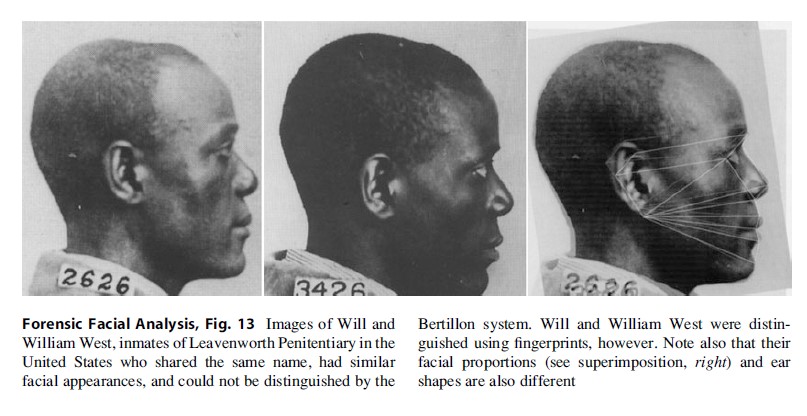

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 13 Images of Will and William West, inmates of Leavenworth Penitentiary in the United States who shared the same name, had similar facial appearances, and could not be distinguished by the Bertillon system. Will and William West were distinguished using fingerprints, however. Note also that their facial proportions (see superimposition, right) and ear shapes are also different

Forensic Facial Analysis, Fig. 13 Images of Will and William West, inmates of Leavenworth Penitentiary in the United States who shared the same name, had similar facial appearances, and could not be distinguished by the Bertillon system. Will and William West were distinguished using fingerprints, however. Note also that their facial proportions (see superimposition, right) and ear shapes are also different

Some research, such as that of Mardia et al. (1996), Yoshino et al. (2000), and Evison et al. (Evison et al. 2010; Evison and Vorder Bruegge 2010), has explored the potential for measurement-based and probabilistic methods of facial comparison using features demonstrable to a lay person. This approach is provisionally able to distinguish the famously similar appearances of Will and William West (Fig. 13), an early case of persons distinguished and identified from their fingerprints by the FBI.

Presently, however, investigation relies on recognition from CCTV images and prosecution on the admissibility of eyewitness identification as evidence in court. Although some investigators coin CCTV image analysis the third forensic discipline (Jon 2009) after dermatoglyphic fingerprinting and DNA analysis, the allusion is somewhat misleading as there is no definitive forensic science of facial image comparison.

Bibliography:

- ACPO (2009) Facial identification guidance. Association of Chief Police Officers, London. http:// www.acpo.police.uk/asp/policies/Data/Facial%20ID. pdf. Accessed 20 July 2012

- Anonymous (1999) The strange story of Adolph Beck. Stationery Office, London

- APCO (2012) Public encouraged to identify criminals with mobile app. Br Assoc Public Saf Commun Off J. http://www.bapcojournal.com/news/fullstory. php/aid/2239/Public_encouraged_to_identify_criminals_with_mobile_app.html. Accessed 30 July 2012

- Bertillon A (1885) Identification anthropome´trique: instructions signale´tiques. Melun, Paris

- Bromby MC, Plews S (2006) Guidance for evaluating levels of support. FIAG: Forensic Imagery Analysis Group. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm? abstract_id¼1550752. Accessed 20 July 2012

- Bruce V, Henderson Z, Greenwood K, Hancock PJB, Burton AM, Miller P (1999) Verification of face identities from images captured on video. J Exp Psychol Appl 5(4):339–360

- Bruce V, Henderson Z, Newman C, Burton AM (2001) Matching identities of familiar and unfamiliar faces caught on CCTV images. J Exp Psychol Appl 7(3):207–218

- Burton AM, Wilson S, Cowan M, Bruce V (1999) Face recognition in poor-quality video: evidence from security surveillance. Psychol Sci 10(3):243–248

- Cole S (2001) Suspect identities: a history of fingerprinting and criminal identification. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Dessimoz D, Champod C (2007) Linkages between biometrics and forensic science. In: Jain AK (ed) Handbook of biometrics. Springer, Berlin

- Devlin P (1976) Report to the secretary of state for the home department of the departmental committee on evidence of identification in criminal cases. H.M.S.O, London

- Dror IE, Mnookin JL (2010) The use of technology in human expert domains: challenges and risks arising from the use of automated fingerprint identification systems in forensic science. Law Probab Risk 9:47–67

- Dror IE, Charlton D, Peron AE (2006) Contextual information renders experts vulnerable to making erroneous identifications. Forensic Sci Int 156(1): 74–78

- Edmond G (2011) The building blocks of forensic science and law: recent work on DNA profiling (and photo comparison). Soc Stud Sci 41(1):127–152

- Evison MP (2011) Biometrics for forensics. In: van Science Regulator, London. http://www.homeoffice. gov.uk/publications/police/operational-policing/Manual_of_Regulation_22.9.08.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2012

- Russell R, Duchaine B, Nakayama K (2009) Super-recognizers: people with extraordinary face recognition ability. Psychon Bull Rev 16(2):252–257

- Saks M, Koehler J (2005) The coming paradigm shift in forensic identification science. Science 309:892–895

- SWGIT (2012) Best practices for forensic photographic comparison. International Association for Identification: Scientific Working Group on Imaging Technology. http://www.theiai.org/guidelines/swgit/guidelines/section_16_v1-0.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2012

- Vanezis P, Brierley C (1996) Facial image comparison of crime suspects using video superimposition. Sci Justice 36(1):27–33

- Vanezis P, Lu D, Cockburn J, Gonzalez A, McCombe G, Trujillo O, Vanezis M (1996) Morphological classification of facial features in adult Caucasian males based on an assessment of photographs of 50 subjects. J Forensic Sci 41(5):786–791

- Yoshino M, Matsuda H, Kubota S, Imaizumi K, Miyasaka S (2000) Computer-assisted facial image identification system using a 3-D physiognomic range finder. Forensic Sci Int 109(3):225–237

- Tilborg HCA, Jajodia S (eds) Encyclopedia of cryptography and security. Springer, New York

- Evison MP, Vorder Bruegge RW (2010) Computer-aided forensic facial comparison. CRC Press, Boca Raton Evison MP, Dryden I, Fieller NRJ, Mallett XDG,

- Morecroft L, Schofield D, Vorder Bruegge RW (2010) Key parameters of face shape variation in 3D in a large sample. J Forensic Sci 55:159–162

- Grimston J (2011) Eagle-eye of the yard can spot rioters by their ears. The Sunday Times, 20 Nov 2011

- Jon D (2009) Closed circuit television’s key role in modern policing. Doktor Jon’s guide to CCTV and IP video surveillance. http://www.doktorjon.co.uk/pdf/DCI%20Neville%20interview0509.pdf

- Kemp R, Towell N, Pike G (1997) When seeing should not be believing: photographs, credit cards and fraud. Appl Cogn Psychol 11(3):211–222

- Mallett XGD, Evison MP (2013) Forensic facial comparison: issues of admissibility in the development of novel analytical techniques. J Forensic Sci (in press)

- Mardia KV, Coombes A, Kirkbride J, Linney A, Bowie LJ (1996) On statistical problems with face identification from photographs. J Appl Stat 23:655–676

- NRC (2009) Strengthening forensic science in the United States: a path forward. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

- Porter G, Doran G (2000) An anatomical and photographic technique for forensic facial identification. Forensic Sci Int 114(2):97–105

- Rennison A (2008) Manual of forensic science regulation. Home Office, Office of the Forensic

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.