This sample Forensic Science Professions Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

The use of forensic science used in criminal investigation brings the occupations of forensic science and policing into an immediate and interactive relationship.

Regardless of the organizational home of forensic science within or outside of policing organizations, the success or failure of forensic science in support of investigations depends on how well this interaction is managed.

This research paper proposes that the tensions which can sometimes be seen in the current relationship would be reduced if both “occupations” more ideally met the characteristics of a true profession. The paper argues that in the modern world we need to look forward in developing a professional project which recognizes the increased role of the state in the regulation of professions.

Key Issues And Future Directions

Introduction

We trust our health to the physician; our fortune and sometimes our life and reputation to the lawyer and attorney. Such confidence could not safely be reposed in people of a very mean or low condition. Their reward must be such, therefore, as may give them the rank in society which so important trust requires.

(Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, BK I p. 10. As quoted in Macdonald 1999)

To the above should we add, we trust our liberty, safety and just outcomes to our police and law enforcement services, and if so, what role or contribution is made or should be made, by forensic science? Do we have confidence in policing and/or forensic science and do we accord them the “rank” which such trust requires? Adam Smith would not have thought of policing when he wrote Wealth of Nations in 1766, some 63 years before Robert Peel established the Metropolitan Police Force in the United Kingdom. Dating the “formal” start of forensic science will no doubt be dealt with elsewhere in this series but practically it is an invention of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, or the modern world.

The purpose of this research paper is to explore the relationship between policing and forensic science, focusing on how these two “occupations” have developed and what implications this has for that working relationship. The paper will propose that although both occupations will lay some claim to being professions they fall well short in critical areas of full professional status. It will further propose that “confidence” and “trust” of both policing and forensic science would be enhanced if both met more ideally a professional model. Macdonalds’ (1999) concept of a professional project will be used to discuss how the latter might be achieved.

What Differentiates A Profession From An Occupation?

Although there is no single agreed definition of what constitutes a profession all dictionary and encyclopedia definitions of the word “profession” stress key common criteria which invariably include:

- An occupation or vocation requiring, or founded upon, specialist training or education, and,

- The body of persons in such an occupation.

In this sense any occupation has the potential to become recognized as a profession provided there is a specialist body of knowledge which can in some way be defined, codified and persons educated and trained.

The journey from occupation to profession, or “professional project,” typically involves milestones being achieved such as:

- It becoming a full time occupation

- The establishment of formal training and education

- Local and national associations being formed, and,

- A code of professional practice being established.

The national association would commonly develop professional rules and structures aimed at establishing a high degree of autonomy and self-regulation. This concept of professional autonomy is based on three claims that:

- The work of professionals entails such a high degree of skill and knowledge that only fellow professionals can make accurate assessments of professional performance

- Professionals are characterized by a high level of selflessness and responsibility such that they can be trusted to work conscientiously, and,

- In those rare instances in which individual professionals do not perform with sufficient skill or conscientiousness, their colleagues may be trusted to undertake proper regulatory action. (Velayutham and Perera 1995)

Included in the regulatory role of many professional bodies will be some measure of control over qualifications as a pre-requisite for professional practice and a code of practice. It is now well recognized that another hallmark of a profession is the recognition of the need for continuing development and lifelong learning. Finally, professions would “profess” to provide their services in a disinterested way and with an ethic of service to others.

Individuals may purport to deliver their services in a professional way, or meet agreed standards, but this in itself is not sufficient for an occupation to be considered a profession.

Forensic science is delivered by persons with science qualifications but also includes important roles for technicians. The US Department of Labor (Anon 2010) describes technicians as follows.

Science technicians use the principles and theories of science and mathematics to assist in research and development and to keep, invent and improve products and processes. However, their jobs are more practically oriented than these of scientists.

The US Department of Labor also stress that technicians “work under the direction of scientists” and that an appropriate level of qualification is a 2 year or associate degree, although of interest is that it states biological and forensic science technicians usually require a bachelor’s degree.

Other definitions of technician draw out the key differences between a scientist and technician as being

- Level of entry qualification (although this is increasingly becoming blurred!)

- Technicians will usually have a vocational qualification

- Technicians have a more practical understanding which will usually include a more in depth understanding of specific techniques than a scientist

- Technicians may have their own work structure and hierarchy but generally will come under the supervision of a scientist. Technicians will often have a formal representative body or association which may even offer formal certification but these groups would not normally be considered professional groups although meeting many of the tenets of a profession.

Forensic science is characterized by its multidisciplinary nature and many commentators would consider some aspects of forensic science are in fact more technical than scientific. For example, are crime scene examination and some aspects of fingerprint examination technician work or scientific work? In the context of this research paper all aspects of forensic work will be considered capable of either meeting the requirements for professional status or evolving towards this status.

The study of professions has attracted considerable attention from social scientists. It is beyond the scope of this research paper to explore in any detail the history of the sociological study of the professions but the reader is referred to two key books on this subject by Larson (1977) and Macdonald (1999). In the context of policing Rohl (1990) suggested that Australasian police should adopt Witham’s (1985) “attribute” approach which defines a profession around eight characteristics. These are,

- Operates as an organized body of knowledge, constantly augmented and refined,

- Involves a lengthy training/education period,

- Operates so as to serve its clients best,

- Operates autonomously and exercises control over members,

- Develops a community of practitioners through professional standards,

- Enforces a code of ethics and behavior,

- Establishes uniform standards of practice, and,

- Provides full professional mobility.

An alternative approach is that of Klegon (1978) who proposes two aspects to define a profession, an internal dynamic and an external dynamic. The internal dynamic relates to the strategies used by the profession such as establishing a code of practice whilst the external dynamic relates to the economic, political, social and intellectual influences which cannot be the exclusive domain of the “profession.”

Allen (1991) has grouped Klegon’s strategies as follows

- Formulation of a code of ethics: once formulated, this code must be promoted as a symbol of the desire of the profession to serve the public.

- Delineation of the area of expertise: exclusive domain of practice must be identified and protected from encroachment, the knowledge base of the profession validating the professional claim.

- Control of education and entry: education should be university based and closely monitored by the professional association(s). Further education might be required before entrance to the association(s).

- Definition of competence levels: promotion of differing classification of membership with reward in prestige and status for those who attain higher levels of expertise.

- Determination of standards: utilizing their autonomy, the profession will determine their own standards of practice.

- Image building: public promotion of positive image of the profession and by convincing the public of its professionalism, the occupation will be rewarded with professional recognition and status.

- Professional unification: the profession must be united as factionalism undermines public confidence.

- Achieving a relationship with the State: a balanced relationship with the State is required and achieved through legislative recognition and registration.

The final point above is an important contemporary issue for professions. In order to achieve a monopoly, or at least licensure and control, a profession must have a special relationship with the State, sometimes called the regulative bargain. Macdonald (1999) makes the point that even when a profession has an apparent monopoly it may still have to compete in the market against others who can provide similar, substitute or complimentary services. It must therefore at least defend and probably enlarge the scope of its activities or its jurisdiction.

This will be discussed further in relation to both policing and forensic science.

Medicine And The Law: Classical Professions: Can Policing And Forensic Science Learn From These Professions?

Medicine and the law are often quoted as examples of professions against which any occupation aspiring to achieve professional recognition should be compared. In this context it is important to more fully understand how medicine and the law achieved professional status as “classic” disciplines in a more modern era. The reality is that this is far from a simple story and often the simplified version is that of the development of the Anglo-American model. Macdonald (1999) analyses in depth the emergence of medicine and law as professions in Britain, the United States of America, Germany and France against a matrix of their history and different state systems. The striking, fact is that the evolution of both “professions” is very different indeed across even these four countries. Hence, it is a gross oversimplification to consider that there is a global shared professional model for either medicine or the law.

For example, Macdonald argues that the underlying canvass against which medicine and the law emerged in Britain goes back to an ancient and historically low level of state involvement and bureaucracy which meant the extension of state power over the institutions of civil society emerged relatively late in Britain. Although both professions are linked to the state, their high level of autonomy originates in practices and forms that go back to the Middle Ages and which had not been subordinated to the “civil service.” Importantly medicine and the law in Britain were able to regulate their own education and training and, hence, control entry to their professions. The role of academic institutions by contrast has not been controlling but merely delivery of what the professions deem necessary as an “entry” to their professions.

The evolution of medicine and the law in the United States is more complex and heavily influenced by a populist climate and a desire to open knowledge based occupations postindependence to all. For example, Macdonald (1999) states that “in response to these state pressures legislatures deprived the medical societies of their licensing powers and American medicine was reduced to a condition of factional disorganisation.” (at p. 83)

Because medicine and the law were deprived of their organizational base and traditional values seen in Britain they had to rely on their expert knowledge as a basis for claim to special recognition. The lack of an organization also meant the universities played a much more important role in passing on knowledge than was the case in Britain.

In the late 1880s as professional bodies reappeared “the chief bases of their ‘professional project’ were their modern knowledge and the institution in which it was lodged, the university.” (Maconald 1999 at p. 84)

If the Anglo-American model had important differences then the evolution of the medical and law professions in France and Germany had even greater differences.

In France the state had a much higher degree of control and responsibility which reduced professional power and increased the influence of universities. Similarly in Germany universities were long established and status was focused on the “educated middle class” or Bildungsburgertum. This was in turn strongly associated with the civil service and academia rather than with the professions.

In summary, Macdonald concludes that “the political ideology in America is a compound of nationalism, liberalism and populism while in Britain traditionalism replaces populism and colours the other two components. In France and Germany these elements are also to be found, but in different proportions and with the important addition of a centralised state, less penetrated by civil society.” (at p. 97)

Hence, it is probably unhelpful to refer back to the “classic” form of knowledge and development of professions for a “modern” society. Those occupations seeking to now achieve professional recognition need to understand that specialist knowledge is now more complex and more organized into disciplines (arguably more divided). There is now a general reluctance for the state to grant a special position. However, the state may see value in using professional bodies as an instrument of regulation.

Knowledge And The Professions

Adam Smith, quoted at the opening to this research paper, was one of the leaders in the “enlightenment.” A consequence of this movement was the exponential growth in knowledge and so called cognitive growth (Gellner 1988, p. 116). In premodern society knowledge was tightly controlled, owned and difficult (even dangerous) to question. Professional knowledge in the modern world is more complex. In one sense knowledge is now open to all, irrespective of status. Knowledge is no longer under the “guardianship” of a few. In this changed paradigm professionals increasingly will rely on certification and credentialing of higher level qualifications to underpin their claims to being a profession. Macdonald (1999, p. 163), proposes that to understand professions the starting point must be to define professional work. The context of professional work, the control of that work differentiating in types of work and the notion of jurisdiction, previously mentioned, are all important in the profession laying claim for its work. However, he argues that the quality that characterizes professional work at a knowledge level is the concept of abstraction. Abbott (1988) captures this in the following quote “.. .abstraction is the quality that sets interprofessional competition apart from competition among occupations in general. Any occupation can obtain licensure (e.g. beauticians) or develop a code of ethics (e.g. real estate). But only a knowledge system governed by abstractions can redefine its problems and tasks, defend them from interlopers, and seize new problems – as medicine has recently seized alcoholism, mental illness, and hyperactivity in children, obesity, and numerous other things. Abstraction enables survival in the competitive system of professions.” (1988, p. 9)

However, the concept of professional work needs to be more than about technique. In the modern world the possessor of knowledge and technique adds value through the exercise of professional judgment. The ever increasing move to standardization and codification has benefits and value and arguably, makes knowledge more accessible to a more educated public. However, taken to extremes (perhaps the Crime Scene Investigation or CSI effect?), this can undermine the role of professionals to apply appropriate cognitive processes encapsulated as professional judgment.

The Concept Of A Professional Project

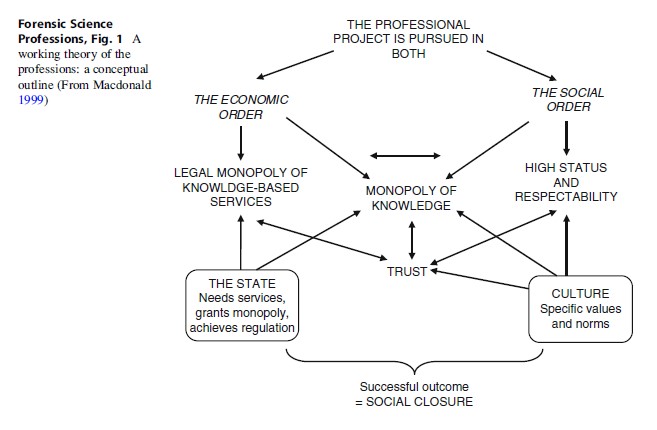

The professional project is the term Macdonald uses (1999) to present a conceptual model for the professions (Fig. 1).

This model brings together the matrix of factors which any occupation seeking to achieve recognition as a profession must consider. Policing and forensic science are assessed against this model and important differences identified which have implications for how these two occupations interact in a broader criminal justice system.

Toward A Policing Professional Project

The professionalization of police has been the subject of an enormous international literature and it is simply out of scope to review this literature in this research paper. As was seen for medicine and law even the Anglo-American “story” of the development of these professions shows two quite distinct pathways. Similarly with two continental European countries they showed significant differences.

Hence, international interest in professionalization of policing will not necessarily translate into a universal model. In this regard the professional project is a more useful concept as it recognizes in particular the role of the state and culture as key drivers. These influences will be significant variables at a national level. For example, the role of police is influenced by the legal system and how it operates.

The starting point for any profession is defining a body of knowledge. It can be argued that there is sufficient specialist knowledge relevant to policing to constitute a body of knowledge although there is no broad agreement as to the academic level of that knowledge. It is certainly not the case that even a vocational qualification is a pre requisite for entry to policing in many countries. In Australia the then Australasian Police Ministers Council (APMC) in 1990 agreed to five major outcomes necessary to attaining full professional status. One of these was that national education standards and formal higher education qualifications were necessary for full professional status.

In 2001 the Australasian Police Professional Standards Council (APPSC) was tasked with advancing police professionalization. Suffice to say that although some jurisdictions in Australia have committed to graduate level entry, and others support an associate degree or vocational equivalent, there is still no general acceptance that police studies (and hence knowledge) are sufficiently distinct to form a necessary body of specialist knowledge. Stone and Travis (2011) in a paper titled “Toward a New Professionalism in Policing” state that “for any profession to be worthy of that name, its members must not only develop transportable skills but also commit themselves both to a set of ethical precepts and to a discipline of continuous learning.” Further, they observed that if the values of policing are really professional and not local, what is needed is a genuine national coherence in the skills, training and accreditation of police. (Stone and Travis 2011, p. 19).

The title of the above paper does send out a warning and that is not to confuse “professionalism” with developing a profession. As has been discussed previously it is entirely possible to deliver a professional service without meeting the tenets of a profession.

It is yet to be seen if the prediction of Stone and Travis (2011, p. 19) that “the attraction of the new professionalism is likely to feed a flowering of specialist professional associations, bachelors and masters degree programs” will be achieved.

Regrettably in 2012 the aspiration of the APMC stated in 1990, of formal higher education qualifications, have not been achieved in Australia. Certainly progress has been made in developing national educational standards but these have been set at a technician, vocational level.

By 2006 yet another report prepared for the Police Commissioners of Australasia identified six key objectives for the attainment of full professional status, these being:

- Develop a definition of the profession of policing.

- Implement university-based education for policing.

- Develop a body of knowledge.

- Propose ongoing professional development.

- Develop registration and standards for policing.

- Establish a professional body for policing. (Lanyon 2007)

It is disturbing that even in an advanced country such as Australia there is still a need to develop a definition of the profession of policing. A further 6 years has seen little hard progress towards the realization of any of these goals.

It has also been observed that much of the discussion about professionalization of policing takes place at a senior manager and executive level and broad commitment by “rank and file” members is questionable.

Perceptively it has been said that “occupations that fail to lead the agenda in advancing their own professionalization may well forfeit that role to other more influential agencies” (Lanyon 2007, p. 122). Following a major review of police leadership and training in England and Wales (2011). Neyroud recommended the creation of a new professional body for policing. This recommendation has been accepted by the UK government who announced in December 2011 their intent to establish a new police professional body in 2012. Although the governance structure for this new body has not yet been made public it seems clear that there will be a greater degree of central government regulation and control of the professional aspects of policing. The Police Minister is quoted as saying that “it’s striking that while doctors, lawyers, teachers and nurses have their own professional bodies, police officers do not.” (Anon 2011a)

Indications are that this new body will have an independent chair from outside the police establishment and that it will eventually receive a royal charter similar to other professional bodies.

As discussed earlier in this research paper state interest in professions is likely to increase with greater formal regulation. The lack of genuine professional member organizations in policing does not place the practitioners in a strong position to influence their journey towards full professional status.

Furthermore, policing as an occupation no longer has a monopoly of services with private security and other government enterprises sharing the “market.”

It would probably be an exaggeration to say that there is a crisis in policing or with the public view from a status and respectability viewpoint. However, clearly this would vary widely at a global level. However, ongoing issues with police corruption and integrity do nothing to support the move to policing being accepted as a profession and police more often than not are increasingly subject to additional external oversight through independent integrity commissions. In this regard policing also falls short of the “trust” awarded through self-regulation to professions.

A final aspect of a profession which is worthy of comment is that of full professional mobility. Implicit in this criterion is that this would be facilitated by mutual recognition of qualifications, training and rank or level. With some exceptions, and at senior police ranks, policing falls well short of full professional mobility.

Towards A Forensic Science Profession

Robertson (2011a) has discussed the issues relevant to assessing whether or not forensic science can meet the criteria of a true profession. In this discussion the professional project model will be used as the template against which this assessment will be made. This follows the same approach as for policing and enables a comparison of the status and progress of these two occupations towards achieving professional status.

The first criterion is that of a body of knowledge. In addressing this criterion it is important to consider what is the relevant body of knowledge. If forensic science is considered to be merely the application of core sciences such as biology, chemistry and physics to addressing science issues which may end up in a legal setting, then that body of knowledge is science knowledge. While this body of knowledge is always to an extent tentative and evolving, nobody would argue that science knowledge is not a sound basis underpinning all science based professions. It can be argued that the forensic dimension is merely context and in this respect forensic science is no different from any other occupation which relies on the application of science. The issue then becomes not one of underlying knowledge but rather one of how well that knowledge is applied and used. In the modern world, with a heavier focus on disciplines, forensic science can be considered to be simply a discipline or group of disciplines.

The US National Academies of Science (NAS) report on “strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward” (Anon 2009) commented that the: “forensic science enterprise is hindered by its extreme disaggregation – marked by multiple types of practitioners with different levels of education and training and difference professional cultures and standards for performance.” (at pp. 5–11)

The report also observed that “of the various facets of under-resourcing, the committee is most concerned about the knowledge base,” further commenting on the lamentable state of funding for forensic science research.

Crispino (2011) has argued that there is a unique scientific basis for recognizing forensic science as a distinct discipline. Although it can be argued that it is a “chicken and egg” situation the existence of numerous academic programs on forensic science could be put forward as further evidence in support of the proposition that there is a specific body of knowledge. At least some of these education programs pre date the “CSI” driven expansion in forensic programs within universities and some have been around for several decades. A pragmatic view of the world would recognize that forensic science is an academic specialization, is here to stay, and that there are sufficient unifying concepts for it to be considered a distinctive discipline. This is not to deny the need to improve the underpinning knowledge base and the need for a much enhanced research effort. As present there is no statutory requirement for entrants to the forensic profession to have a specific forensic qualification. Whilst there is an emerging trend toward accreditation of forensic education programs and toward individual certification, including commitment to ongoing education and training or continual professional development, these fall short of being mandatory requirements for professional practice. In this sense forensic science can be considered to be at best an immature profession with respect to its knowledge base (and any sense of a monopoly of knowledge) and the related education and academic/research structures.

Although a degree is a requirement of some forensic membership organizations for levels of professional recognition, many forensic occupations either have no educational pre-requisites for entry or these are set at a lower than degree level. In itself this does not preclude forensic science being considered a profession as it is possible to have a technician level within a professional structure.

Perhaps more worrying is that the culture of forensic science falls short of what would be expected of a profession, and specifically, the lack of acceptance, or commitment to research and development. (Robertson 2011b). It has also been observed that at least for some aspects of forensic science the cultural setting is closer to policing than science.

The question arises as to whether or not forensic science as an occupation should be part of a policing organization. The NAS report (Anon 2009) was clear on this point in recommending “removing all public forensic laboratories and facilities from the administrative control of law enforcement agencies or prosecutor’s offices.” (at pp. 5–17)

The factual situation is that there are numerous models and organizational structures at a global level through which forensic science is delivered (Robertson 2012). There is no ideal model and the “state” largely determines its needs, service delivery model and grants either monopoly or creates a market. An example of this is the current situation in England and Wales where the “state” has created a market for the provision of some aspects of forensic science, going as far as withdrawing from any public ownership of forensic laboratory services. However, even here it needs to be recognized that the “state” retains ownership of the majority of forensic science through its police services provision of crime scene, fingerprint and other forensic disciplines. One mechanism introduced in England and Wales to ensure scientific standards are met, has been the establishment of the Office of the Forensic Regulator (Anon 2011). At a level below the “state” level the third party accreditation of forensic services, assessed against relevant standards (most often ISO – 17025), goes someway to regulating levels of professional delivery if not the profession.

As a profession is the “body of persons” in that occupation the role of representative organizations is important. Forensic science societies and organizations play a useful and increasingly important role in “professionalising” the profession. However, these fall well short of the status and authority of similar groups in professions such as medicine, the law or pharmacy. As has been discussed earlier in this research paper it is somewhat misleading to compare an evolving profession today, with the structures seen in the “Anglo” experience of pre-modern professions such as medicine and the law. In today’s world the “state” is likely to relinquish less autonomy and more likely to demand greater regulation of emerging professions.

Notwithstanding, as with policing, forensic science would benefit from more mature member organizations focused on representing the professional interests of their members. It is perhaps surprising that forensic science has “escaped” the degree of formal regulation applied to more mature professions (see Robertson 2011a, discussing the regulation of Health professions in Australia).

Finally, there are limited barriers to the mobility of forensic science professionals and these relate more to employer barriers than to any science based barriers, provided the “employee” can meet the organizational educational entry requirements. The one exception to this is perhaps in some police services where there is still a requirement for the forensic employee to be a police member.

Conclusions

Forensic science and policing cannot escape the close interaction essential to the investigation of crime, whether or not, they belong to the same or different organizations. This “marriage” may be seen by some as a “marriage made in hell” and by others in a more positive light but, like any marriage, it will only work where both parties work together and where the relationship matures and evolves over time. Forensic science is still a relatively new occupation, far less a new profession. Policing is an older occupation but still largely a product of modern times. In this research paper it is argued that the relationship between forensic science and policing would benefit from both occupations maturing into genuine professions. The professional project is a useful way to describe the journey ahead should forensic science and policing wish to evolve to full professional status. The practical working interactions between police and forensic science would surely be improved if both occupations more closely met the ideal requirements of a profession with shared core values.

Bibliography:

- Abbott A (1988) The system of professions. University Of Chicago Press, London

- Allen K (1991) In pursuit of professional dominance: Australian accounting 1953–1985. Account Audit Account J 4(1):51–67

- Anon (2009) Strengthening forensic science in the United States: a path forward. National Research Council of the US. National Academics of Science. At http:// www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id¼12589

- Anon (2010) Bureau of labor statistics. At http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos115.htm

- Anon (2011a) Home secretary outlines plans for new police professional body. At www.homeoffice.gov.uk/mediacentre/press-releases/police-professional-body

- Anon (2011b) Codes of practice and conduct for forensic science providers and practitioners in the criminal justice system. Version 1.0. Pub. Crown copyright

- Crispino F, Ribaux O, Houck M, Margot P (2011) Forensic science – a true science? Aust J Forensic Sci 43:157–176

- Gellner E (1988) Plough sword and book. Collins Harvill, London

- Klegon D (1978) The sociology of professions: an emerging perspective. Sociol Work Occup 5(3):259–283

- Lanyon JJ (2007) Professionalisation of policing in Australia: the implications for police managers. In: Mitchell M, Casey J (eds) Police leadership and management. Federation Press, Annandale, pp 107–123

- Larson MS (1977) The rise of professionalism. A sociological analysis. University Of California Press, London

- Lawless C (2010) A curious reconstruction?. The shaping of ‘Marketized’ forensic science. Discussion Paper no. 63. Pub. LSE Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation

- Macdonald KM (1999) The sociology of the professions. Sage, London

- Neyroud P (2011) Review of police leadership and training. At http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/ consultations/rev-police-leadership-training/

- Robertson J (2011a) Forensic science – a true profession? Aust J Forensic Sci 43:105–122

- Robertson J (2011b) Truth has many aspects. Sci Justice. doi:10.1016/j.scijust.2011.11.001

- Robertson J (2012) Principles for the organisation of forensic support. In: Siegel JA, Saukko P (eds) Encyclopaedia of forensic sciences, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Oxford (at press)

- Rohl T (1990) Moving to a professional status. Police J (S Aust) 71(6):6–9

- Silverman B (2011) Research and development in forensic science: a review. At http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/ publications/agencies-public-bodies/fsr/forensic-science-review/

- Stone C, Travis J (2011) Towards a new professionalism in policing. In New perspectives in policing, NIJ/Harvard Kennedy School. At http://www.ajp.usdoj.gov/nij/ topics/law-enforcement/executive-sessions

- Velayutham S, Perera H (1995) The historical context of professional ideology and tension and strain in the accounting profession. Account Historians J 22(1):81–102

- Witham DC (1985) The American law enforcement chief executive: a management profile. Police Executive Research Forum, Washington, DC

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.