This sample Geographic Profiling Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Geographic profiling is a criminal investigative methodology for analyzing the locations of a connected series of crime to determine the most probable area of offender residence. Its major function is suspect prioritization in investigations of serial crime. The technique is based on the theories, concepts, and principles of environmental criminology. Crime pattern, routine activity, and rational choice theories provide the foundation for understanding the target patterns and hunting behavior of criminal predators.

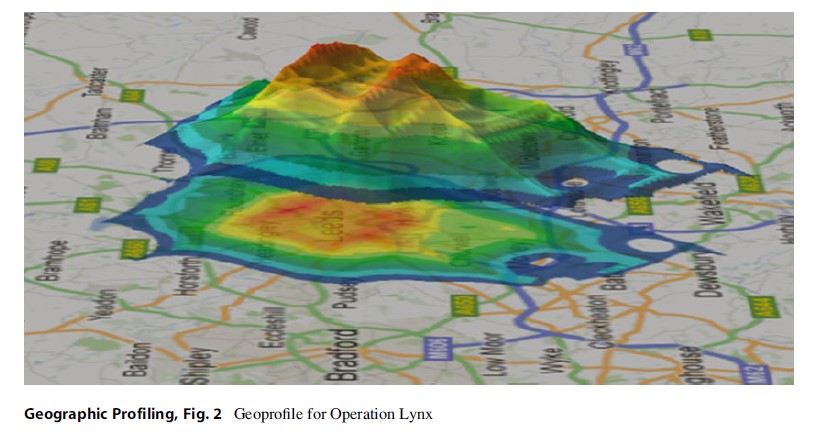

These theories suggest a method for describing the mathematical relationship between offender travel and likelihood of offending. This relationship can be described by a buffered distance-decay function that looks in cross-section rather like a volcano with a caldera. The function is encoded in a computer algorithm. Geographic profiling uses specialized crime-mapping software based on this algorithm to determine the most probable area of offender residence from the spatial pattern of the crimes.

Geographic profiling has turned out to be a robust and versatile methodology. Originally developed for analyzing serial murder cases, it was subsequently applied to rape, arson, robbery, bombing, kidnapping, burglary, auto theft, credit card fraud, and graffiti investigations. A number of innovative applications outside law enforcement also exist, with geographic profiling being used in military operations, intelligence analysis, biology, zoology, epidemiology, and archaeology.

Introduction

Geographic profiling is a criminal investigative methodology for analyzing the locations of a connected series of crime to determine the most probable area of offender residence (Rossmo 2000). Its major function is suspect prioritization in investigations of serial crime. A criminal investigation involves two tasks – finding the offender and proving guilt. Guilt can only be established by a confession, a witness, or through physical evidence. The task of finding an offender, a particular challenge in a “whodunit” investigation of a stranger crime, involves collecting, prioritizing, and evaluating suspects. High profile cases often have thousands of suspects and consequent problems of information overload. In such situations, geographic profiling can assist in case information management.

Geographic Profiling

History

Geographic profiling is typically employed in cases of serial violent or property crime, though it can be used in investigations of single crimes involving multiple locations or significant aspects of geography (Davies and Dale 1995; KnabeNicol and Alison 2011). Police have long used ad hoc mapping efforts to support certain criminal investigations. The first recorded use of investigative spatial analysis was during the Hillside Stranglers investigation in 1977. The Los Angeles Police Department analyzed the sites where the murder victims were abducted, their bodies dumped, and the distances between these locations, enabling them to identify the area where the killers were based. A similar analysis, using spatial means and distance-time factors, was conducted in 1980 during the Yorkshire Ripper inquiry in England (Kind 1987). More sophisticated models emerged from research conducted at Simon Fraser University’s School of Criminology in Canada (Rossmo 1995). The technique was first implemented operationally in the Vancouver (British Columbia) Police Department’s Geographic Profiling Section in 1995.

Theory

Geographic profiling is based on the theories, concepts, and principles of environmental criminology. Crime locations are not distributed randomly in space but rather are influenced by the road networks and features of the physical environment. This focus on the crime setting – the “where and when” of the criminal act – offers a conceptual framework for determining the most probable area of offender residence. Environmental criminology is interested in the interactions between people and their surroundings and views crime as the product of offenders, victims, and their setting (Brantingham and Brantingham 1981, 1984). The three theories underlying geographic profiling – crime pattern (Brantingham and Brantingham 1981, 1993), routine activity, and rational choice (Clarke and Felson 1993) – provide the foundation for understanding the target patterns and hunting behavior of criminal predators.

Computer Systems

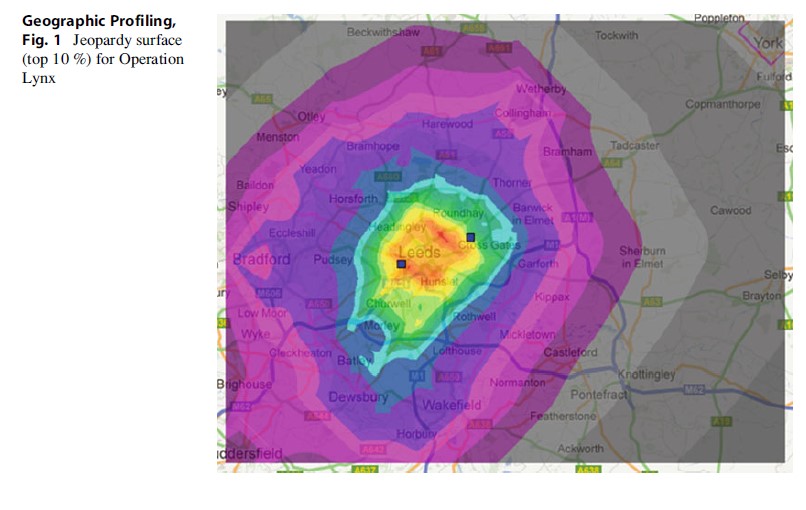

Geographic profiling uses specialized crime-mapping software to determine where an offender most likely lives. The mathematical relationship between offender travel and probability of offending can be described by a buffered distance-decay function that looks, in cross-section, rather like a volcano with a caldera. The function is encoded in a computer algorithm. Working from the point pattern of the crime locations, the computer software produces a jeopardy surface – a three-dimensional probability surface – outlining the most probable area of offender residence (see Figs. 1 and 2 below). Those positions higher on the jeopardy surface (colored red) are more likely to contain the offender’s residence, those lower, less likely. A police investigator can then prioritize suspect addresses or other locations by their position on this probability surface.

A geographic profiling program includes an analytic engine, geographic information system (GIS) capability, database management, and powerful visualization tools. Rigel, based on the Criminal Geographic Targeting (CGT) algorithm developed in 1991 at Simon Fraser University, was the first commercial geographic profiling system. Two similar geographic profiling programs, CrimeStat and Dragnet, primarily used for research rather than police operations, were later released in 1999.

Law enforcement agencies can use geographic profiling software to optimize their limited resources. The performance of a geoprofile is determined by a measure called the hit score percentage (HS%), defined as the ratio of the size of area that has to be searched, following the geoprofile prioritization, before the offender’s base is found, to the total hunting area. For example, if the crimes in the series covered 10 square miles, and the geoprofile located the offender in 1.5 square miles, then the HS% would be 15%. The smaller the HS%, the more precise the geoprofile’s focus and the better its performance. An evaluation of geographic profiles prepared for operational cases that were eventually solved showed that the mean HS% was 5 % and the median 3 % (Rossmo 2011).

Process

The process of generating a geographic profile involves a number of steps, beginning with determining which crimes are connected in a series, evaluating the case information, creating the geoprofile, and finally recommending investigative strategies. This process is described in more detail below.

Linkage Analysis

The investigation of a crime series starts with determining which specific offenses are connected together. This procedure is known as linkage analysis or comparative case analysis. Every crime in the pattern can be considered a piece in a jigsaw puzzle; the more pieces, the more information; the more information, the more detailed the overall investigative picture. Linkage analysis identifies case similarities and common suspects, leading to information sharing between detectives and different police jurisdictions. When a case is solved, more crimes may be cleared and the courts can sentence convicted offenders more appropriately.

A linkage analysis requires the comparison of similarities versus differences for both connected and unconnected crimes; connected crimes should show more similarities than differences and unconnected crimes, more differences than similarities. There are three main methods used to link crimes: (1) physical evidence; (2) offender description; and (3) crime scene behavior (Rossmo 2000). If present, physical evidence such as DNA or fingerprints can establish crime linkage with certainty. In contrast, the other two methods are probabilistic in nature; witness descriptions vary in their accuracy, and offenders do not always exhibit the same modus operandi. Signature – unique behaviors not required for the commission of the crime, such as certain fantasy-based sexual routines in a rape series or the inscription of “FP” (for “fair play”) by the New York Mad Bomber – provides a solid link if present; unfortunately, signature is rare. Proximity in time and place between crimes significantly increases their likelihood of being connected.

After a linkage analysis has been completed, the connected crime locations, distinguished by site type, are entered into the system by street address, latitude and longitude, or digitization. These optional entry methods reflect the reality that crime can happen anywhere – houses, parking lots, back alleys, highways, parks, rivers, and even mountain ravines.

Considerations

An exploratory analysis of the data is next conducted. Several different crime factors and environmental elements need to be considered in the construction and interpretation of a geographic profile:

- Crime sites – While the locations of the crimes are essential to a geographic profile, the types of crime sites are also important. A homicide, for example, can involve separate or combined encounter, attack, murder, and body disposal sites; each site type has a separate analytic meaning.

- Temporal factors – When the crimes occurred (date, day of week, and time of day) and their chronological order provide valuable context for understanding the crime sites. Temporal information may also provide insight into the offender’s routine activities.

- Hunting style – A criminal’s hunting method (defined as the search for, and attack on, a victim or target) influences his or her crime site pattern (Beauregard et al. 2011). Hunting style is therefore an important consideration in geographic profiling.

- Target backcloth – The target backcloth is an opportunity surface representing the availability of potential targets or victims in a given area. An offender’s choice options may be limited if the target backcloth is constrained or patchy (e.g., a criminal preying on street sex workers in a red light district). This may reduce the importance of certain types of crime sites (victim encounters) in the preparation of a geographic profile.

- Arterial roads and highways – People, including criminals, do not travel as the crow flies. They follow street layouts and are more likely to travel along major arterial routes, freeways, or highways. Crimes often cluster around freeway exits.

- Bus stops and rapid transit stations – Offenders without vehicles may use public transit or travel along bicycle or jogging paths. The locations of these routes and their access points may be an important consideration for understanding the crime patterns of such offenders.

- Physical and psychological boundaries – Movement is constrained by physical boundaries such as rivers, lakes, ravines, and highways. Psychological boundaries, resulting from socioeconomic, ethnic, or race differences, also influence movement.

- Zoning and land use – Zoning (e.g., residential, commercial, industrial) and land use (e.g., stores, bars, businesses, transportation centers, major facilities, government buildings, military institutions) provide important keys as to why an offender may have been in a particular area.

- Neighborhood demographics – Some sex offenders prefer victims of a certain racial or ethnic group. These groups may be more common in certain neighborhoods than in others, affecting spatial crime patterns.

- Displacement – Media coverage or police patrol presence can cause spatial displacement, affecting the locations of subsequent crime sites. Any displacement issues have to be compensated for in a geographic profile.

Creating The Geoprofile

Once all these various factors are considered, a scenario, involving a subset of crime locations most relevant for determining the offender’s residence, is created (e.g., non-independent crime sites will be excluded). The next stage is the actual generation of the geographic profile. Conducting hundreds of thousands of iterations of its criminal hunting algorithm, the software assigns probability values (depicted with a color spectrum) to each pixel in what is typically a 40,000-pixel grid overlaid on a map of the crime sites. The final output is a color two-or three-dimensional map that shows the most likely area of offender residence (see Figs. 1 and 2 below). The geoprofile can then be used as the basis for a number of police investigative strategies.

Investigative Strategies

The function of a geographic profile is to focus a criminal investigation. Police agencies have employed a number of strategies over the past 20 years that take advantage of this spatial prioritization. The development of these approaches has been an ongoing interactive process involving investigator input and operational experience (Daniell 2008). Geographic profiling investigative strategies can be broadly divided into suspect-based and area-based approaches, depending on whether individuals or locations are being prioritized. It should be emphasized that a geographic profile is only one of many techniques in the detective’s repertoire. However, it can increase effectiveness and efficiency and, in some situations, make possible an investigative approach that would otherwise not be feasible.

Suspect-Based Strategies

Suspect prioritization involves the assessment of individuals, including suspects, persons of interest, and known criminals. One of the benefits of geographic profiling is the ubiquity of address-based record information (estimated to be as high as 85 %). Potential suspects and investigative leads can be found in a variety of databases: police dispatch, record management, and jail booking systems, sex offender registries, and parolee and predatory violent criminal lists.

Data banks are often geographically based, and parole and probation offices, mental health clinics, social services offices, schools, and other agencies located in prioritized areas may provide information of value. Several commercial companies offer law enforcement agencies the ability to search multiple personal information databases. Their systems (e.g., Accurint and AutoTrack) use proprietary data-mining algorithms to sample and select large quantities of data electronically and assign them to individual profiles.

A department of motor vehicles (DMV) record search for a suspect vehicle can be focused by cross matching an offender’s description from driver’s licenses files and prioritizing the results using geographic profiling. The combined search parameters act as a linear program to produce a manageable list of records.

Area-Based Strategies

Area prioritization involves the allocation of police resources for such activities as surveillance, canvassing, and directed patrolling (for an interesting case example involving a serial burglar, see Rossmo and Velarde 2008). It has also been used to focus intelligence-led DNA screens (“bloodings”) in which individuals are prioritized based on geography, criminal record, age, and other relevant criteria. In certain missing person cases that are suspected homicides, geographic profiling can help determine probable body disposal sites or burial areas if a suspect has been identified.

Operation Lynx

Operation Lynx was the name of a major police operation that investigated a series of five brutal rapes in central England from 1982 to 1995. The first victim was attacked in December 1982 in a parking lot in Bradford by a man with a Scottish accent. The offender forced his way into her car and then drove to a deserted airport where he raped her. A month later, the second victim was abducted in a similar manner from the parking lot of a Leeds hospital. Afterward, the offender abandoned her in an industrial area in the central part of the city. He continued this pattern, raping a woman in Leicester in May 1984 and another in Nottingham in May 1993. The last victim, a student, was attacked in a multistory parking garage in Leeds in July 1995. The offender put crazy glue over her eyes so she could not see him.

These crimes spanned multiple police jurisdictions, resulting in significant investigative problems. Finally, in 1996, the crimes were officially linked. The various police agencies formed Operation Lynx, which eventually became, with over 180 police officers from five different police forces, the largest manhunt in England since the Yorkshire Ripper inquiry. Investigators recovered DNA from semen and blood found at two of the crime scenes, but unfortunately, the offender was not on the UK National DNA Database. They also had a partial fingerprint from one of the victim’s vehicles, though it lacked a sufficient number of points for an automated fingerprint identification system (AFIS) comparison. Investigators then decided to try a manual search of the fingerprint files of West Yorkshire Police – a jurisdiction of two million people. A prioritization scheme, one element of which was geography, was developed to focus the search.

In 1997, the Vancouver Police Department was asked to prepare a geographic profile for the case (Rossmo 2000). Unfortunately, even though each rape involved multiple locations, the crime series was spread over 13 years and several areas, suggesting the offender had operated from different bases. Generating separate geoprofiles for each city would have resulted in the critical loss of information. Investigators, however, had linked a stolen Ford Cortina to the second attack. The owner’s credit card had been left inside the vehicle, and someone had used it to make numerous purchases throughout Greater Leeds. If this person was the rapist, then the geographic profile could also include these locations.

Proceeding on this basis, a geographic profile was prepared from the 20 locations of the Leeds crimes and credit card purchases. The result focused on two neighborhoods in central Leeds – Millgarth and Killingbeck. Consequently, the manual fingerprint search was narrowed by age (35–52 years), criminal record (minor offenses), residence area (Millgarth or Killingbeck), and Scottish origin, among other parameters. In March 1998, after 940 h of examining more than 7,000 prints, a match was made to a man named Clive Barwell. DNA subsequently confirmed he was the rapist. Barwell resided in Killingbeck, and his address was in the top 3.0 % of the geoprofile; his mother, who used to beat him when he was a child, lived in Millgarth. In October 1999, after Barwell pled guilty in court, he was sentenced to eight life terms in prison. He is still a suspect in the murder of a young woman.

Barwell may have been found sooner, but it turned out he was not Scottish. He had faked an accent in order to mislead police. He was also listed as being in prison during the Nottingham attack; an undocumented release gave him the opportunity to rape again.

In the hunt for Barwell, detectives engaged in 24,324 actions, knocked on over 14,000 doors, tested the DNA of 2,177 men, and reviewed an additional 9,945 suspects. A total of 33,628 names were entered in the inquiry’s computer system, more than in any other case in British policing history. Operation Lynx is a dramatic example of the importance of suspect prioritization. Given the multijurisdictional nature and time span of the crimes, the manual fingerprint review would never have been successful without narrowed search criteria and a geographic focus.

Figure 1 shows the top 10 % of the three-dimensional jeopardy surface created with Rigel for Operation Lynx in 1997. Figure 2 shows the full two-dimensional geoprofile; the blue square in the southwest of central Leeds marks Barwell’s address, and the one in the northeast, his mother’s address.

Training

The Vancouver Police Department (VPD) implemented the first geographic profiling training program in 1997. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Ontario Provincial Police, British National Crime Faculty (now part of the Serious Organised Crime Agency or SOCA), and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF), among other agencies, have all had personnel trained in the methodology. The National Law Enforcement and Corrections Technology Center-Southeast Region (NLECTC-SE), working with the VPD, expanded geographic profiling training to property crime investigations in 2001 (Rossmo and Velarde 2008). Training is now available for police investigators and crime analysts internationally through various universities and police agencies. Over 600 people, representing 264 law enforcement, intelligence, and military agencies from 14 countries, including Australia, Canada, England, Wales, Korea, The Netherlands, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, and the United States, have now been trained in geographic profiling.

Future Directions

New Applications

Geographic profiling has turned out to be a robust and versatile methodology. Originally developed for analyzing serial murder cases, it was subsequently applied to rape, arson, robbery, bombing, kidnapping, burglary, auto theft, credit card fraud, and graffiti investigations. It has also been used to refine probability calculations in familial searches of DNA databanks (Gregory and Rainbow 2011). Some of the more interesting applications have included the geoprofiling of payphone locations in a murder case, cellular telephone switch tower sites in kidnapping cases, stores where bomb components were bought, locations of credit card purchases and bank ATM withdrawals in a rape case, and, in a historical analysis, the locations of anti-Nazi postcards left on the streets of Berlin, Germany, during the early 1940s. Geographic profiling has also found a number of innovative applications outside law enforcement, including uses in military operations, intelligence analysis, biology, zoology, epidemiology, and archaeology (Rossmo 2012).

Counterinsurgency And Counterterrorism

Traditional military responses to insurgency attacks in Iraq and Afghanistan, often quasi-criminal in nature, are usually not possible because of the civilian nature of the surrounding population. Counterinsurgency operations therefore require intelligence analysis and some form of investigative response. These attacks have underlying spatial and temporal patterns, enabling the use of geographic profiling by military analysts to determine the most probable locations of enemy bases (Brown et al. 2005; Kucera 2005). For example, urban and countryside insurgency problems have included attacks from improvised explosive devices (IEDs), vehicle bombs, land mines, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), mortars, and snipers. Insurgents typically obtain their heavier armaments and munitions from supply centers – homes, mosques, warehouses, and various other buildings. For geographic profiling purposes, the insurgent attack locations are equivalent to crime sites, while their supply centers are equivalent to offender bases.

Terrorism is a covert threat, and important patterns can be lost in the large volume of data collected by counterterrorism and intelligence agencies. Geographic profiling models can be used to prioritize suspects, tips, and leads. While it has seemed to some that terrorists, with transnational structures and decentralized networks, lack a geographic structure, it turns out that they do. Many minor terrorist actions are ordinary crimes, such as robbery, theft, and credit card fraud. Even major terrorist attacks of targets specifically selected for their symbolism require the establishment of terrorist cells in the areas of operation. In both situations, a geographic relationship exists, whether it is the target determining the locations of the terrorist cell sites or the terrorist cell sites determining the location of the target. Bennell and Corey (2007) retrospectively applied geographic profiling to terrorist bombings in France and Greece. They concluded that when appropriate assumptions are met (an area requiring further research), geoprofiles of terrorism can be accurate. Rossmo and Harries (2011) analyzed the site patterns of Marxist and Jihadist terrorist cells in Turkey and Spain and found they possessed internal geospatial structures that could be quantified.

Biology And Epidemiology

Biologists have adopted geographic profiling models to the study of animal predation. The technique has been used to describe foraging patterns of different colonies of bats in Scotland (Le Comber et al. 2006), discriminate spatial search processes and predict nest locations of bumblebees (Raine et al. 2009; Suzuki-Ohno et al. 2010), and investigate the nonrandom nature of white shark attacks in South Africa (Martin et al. 2009).

Geographic profiling has also been used in epidemiology research to locate the origins of infectious diseases, including contaminated water sources for cholera and mosquitogenic breeding pools for malaria (Le Comber et al. 2011). Source populations of invasive species have been identified from geographic profiles of their current locations (Stevenson et al. 2012). The expansion of geographic profiling to these other domains demonstrates the reach and power of the environmental criminology approach.

Future Improvements

Future improvements in geographic profiling require an integration of both scholarly research and operational experience. One area that requires more study is the journey to crime. While many studies have measured the distance between offenders’ homes and their crime sites, only a few have examined the exact nature of their crime journeys. Rossmo et al. (2011) mapped and analyzed the spatial-temporal patterns of a group of reoffending parolees on an electronic monitoring program with a global positioning system (GPS). Their research revealed the characteristics of actual crime trips and provided a more nuanced understanding of offenders’ spatial patterns. Bernasco (2010) studied the spatial influence of offenders’ residential history on their crime locations. He found past residences still influenced where a criminal offended provided he or she had recently moved and had lived in the prior residence for a period of time. Summers et al. (2010) used maps in interviews of convicted property offenders, gaining insights into how they view space and search for criminal targets.

Combining geo-demographics and other area-based information with the point pattern analysis of geographic profiling is another approach with potential (Rossmo et al. 2004). Levine and Block (2011) developed a Bayesian approach to geographic profiling that integrates historic offender residence data with journey-to-crime estimations. However, while Bayesian models may be useful for prioritizing geographic areas, they cannot be used for suspect prioritization as their calibration is based on known offender residences.

Conclusion

The stranger nature of serial crime creates challenges for police investigations. Geographic profiling can help detectives prioritize suspects and manage information in such cases. It is only one of several available tools and is best employed in conjunction with other police methods. As addresses are a common database element, geographic profiling can be used as a decision support tool in a variety of contexts. The overall geographic pattern of a crime series is just as much a clue as any of those found at an individual crime scene.

Bibliography:

- Beauregard E, Rossmo DK, Proulx J (2011) A descriptive model of the hunting process of serial sex offenders: a rational choice approach. In: Natarajan M (ed) Crime opportunity theories: routine activity, rational choice and their variants. Ashgate, Surrey

- Bennell C, Corey S (2007) Geographic profiling of terrorist attacks. In: Kocsis RN (ed) Criminal profiling: international theory, research, and practice. Humana Press, Totowa, pp 189–203

- Bernasco W (2010) A sentimental journey to crime: effects of residential history on crime location choice. Criminology 48:389–416

- Brantingham PL, Brantingham PJ (1981) Notes on the geometry on crime. In: Brantingham PJ, Brantingham PL (eds) Environmental criminology. Sage, Beverly Hills, pp 27–54

- Brantingham PJ, Brantingham PL (1984) Patterns in crime. Macmillan, New York

- Brantingham PL, Brantingham PJ (1993) Environment, routine and situation: toward a pattern theory of crime. In: Clarke RV, Felson M (eds) Routine activity and rational choice. Transaction, New Brunswick, pp 259–294

- Brown RO, Rossmo DK, Sisak T, Trahern R, Jarret J, Hanson J (2005) Geographic profiling military capabilities. In: Final report submitted to the Topographic Engineering Center, Department of the Army, Fort Belvoir

- Clarke RV, Felson M (eds) (1993) Routine activity and rational choice. Transaction, New Brunswick

- Daniell C (2008) Geographic profiling in an operational setting: the challenges and practical considerations, with reference to a series of sexual assaults in Bath, England. In: Chainey S, Tompson L (eds) Crime mapping case studies: practice and research. Wiley, Chichester, pp 45–53

- Davies A, Dale A (1995) Locating the stranger rapist (Special Interest Series: Paper 3). Police Research Group, Home Office Police Department, London

- Gregory A, Rainbow L (2011) Familial DNA prioritization. In: Alison L, Rainbow L (eds) Professionalizing offender profiling: forensic and investigative psychology in practice. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, pp 160–177

- Kind SS (1987) Navigational ideas and the Yorkshire Ripper investigation. J Navig 40:385–393

- Knabe-Nicol S, Alison L (2011) The cognitive expertise of geographic profilers. In: Alison L, Rainbow L (eds) Professionalizing offender profiling: forensic and investigative psychology in practice. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, pp 126–159

- Kucera H (2005) Hunting insurgents: geographic profiling adds a new weapon. GeoWorld 37(30–32):37

- Comber SC, Nicholls B, Rossmo DK, Racey PA (2006) Geographic profiling and animal foraging. J Theor Biol 240:233–240

- Le Comber SC, Rossmo DK, Hassan AN, Fuller DO, Beier JC (2011) Geographic profiling as a novel spatial tool for targeting infectious disease control. Int J Health Geogr 10:35–42

- Levine N, Block RL (2011) Bayesian journey-to-crime estimation: an improvement in geographic profiling Prof Geogr 63(2):1–17

- Martin RA, Rossmo DK, Hammerschlag N (2009) Hunting patterns and geographic profiling of white shark predation. J Zool 279:111–118

- Raine NE, Rossmo DK, Le Comber SC (2009) Geographic profiling applied to testing models of bumble-bee foraging. J R Soc Interface 6:307–319

- Rossmo DK (1995) Place, space, and police investigations: hunting serial violent criminals. In: Eck JE, Weisburd DL (eds) Crime and place: crime prevention studies, vol 4. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 217–235

- Rossmo DK (2000) Geographic profiling. CRC Press, Boca Raton

- Rossmo DK (2011) Evaluating geographic profiling. Crime Map J Res Pract 3:42–65

- Rossmo DK (2012) Recent developments in geographic profiling. Policing J Policy Pract 6:144–150

- Rossmo DK, Harries KD (2011) The geospatial structure of terrorist cells. Justice Q 28:221–248

- Rossmo DK, Velarde L (2008) Geographic profiling analysis: principles, methods, and applications. In: Chainey S, Tompson L (eds) Crime mapping case studies: practice and research. Wiley, Chichester, pp 35–43

- Rossmo DK, Davies A, Patrick M (2004). Exploring the geo-demographic and distance relationships between stranger rapists and their offences (Special Interest Series: Paper 16). Research, Development and Statistics Directorate, Home Office, London

- Rossmo DK, Lu Y, Fang T (2011) Spatial-temporal crime paths. In: Andresen MA, Kinney JB (eds) Patterns, prevention, and geometry of crime. Routledge, London, pp 16–42

- Stevenson MD, Rossmo DK, Knell RJ, Le Comber SC (2012) Geographic profiling as a novel spatial tool for targeting the control of invasive species. Ecography 35:704–715

- Summers L, Johnson SD, Rengert GF (2010) The use of maps in offender interviewing. In: Bernasco W (ed) Offenders on offending: learning about crime from criminals. Willan Publishing, Cullompton, Devon, pp 246–272

- Suzuki-Ohno Y, Inoue MN, Ohno K (2010) Applying geographic profiling used in the field of criminology for predicting the nest locations of bumble bees. J Theor Biol 265:211–217

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.