This sample History of Green Criminology Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

This research paper provides an overview of work in the developing field of “green criminology” (other terms and definitions will be described below). It discusses the breadth of topics covered in the literature, reviews some key contributions from writers in the field, and draws attention to some future directions for research.

Global extensions of environmental degradation are slowly but persistently breaking into every sphere of human life. Throughout the twentieth century and particularly following changes brought about by the First World War and accelerating after the Second, advanced societies have experienced complexity in their progress and development that has shaped changes in socioeconomic systems and in corresponding and linked criminal activities. Within this process, impacts on the environment have tended to be overlooked until relatively recently. Across the natural and social sciences, the preservation and sustainability of our environment is now recognized as a major issue for the survival of humanity and all species, and within criminology, it is now also being recognized that concerns about environmental harms, crimes, and damage should be given a more prominent place in the field. The consequences of environmental pollution, for example, are dramatic and drastic, including the extinction of plants and animals, poor health outcomes for some population groups, damage to food chains, depletion of natural resources, exacerbation of climate change, and natural disasters stimulated or worsened by human action. Environmental harms have become a topic of public discussion and frequent media reporting, as well as the subject of international conferences and scientific symposia, debates, and meetings of political leaders. In this context, a relevant branch of criminology has emerged and has been referred to as a “green criminology.”

Fundamentals

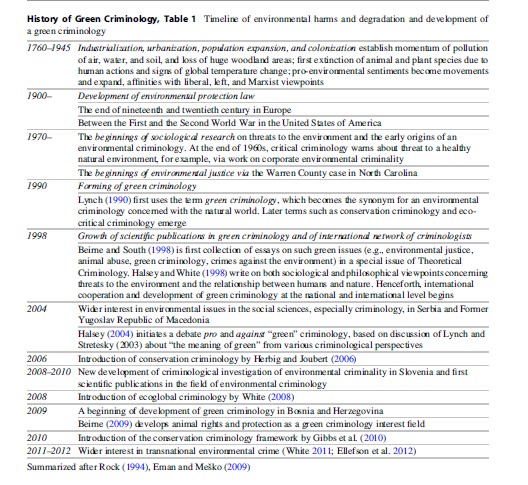

“Green criminology” has grown internationally and is a good example of how the English-language research literature can fail to register and acknowledge pioneering work published in other languages. Opinions about the beginnings and formation of an environmentally sensitive criminology differ. Clifford (1998: 10) suggests environmental criminality is a relatively new field of research within criminology, beginning in the period around the 1970s, while Koser Wilson (1999: 155) states that criminologists showed an interest in environmental crime at a point when the momentum of environmental politics brought such crime within the orbit of criminal sanctions as a part of the criminal-legal system. Pioneering work from Slovenia by Pecˇar (1981) put forward early warnings about new ecologically damaging forms of criminality (Eman et al. 2009: 584) and offered an etiology of forms of environmental criminality in Slovenia, defining the role of criminology and sciences related to this and setting out tasks necessary for the control of offending institutions. However, despite his forecasts and prescriptions, there was little subsequent interest in such a green criminology in Slovenia, and with no English-language translation, this research paper made no wider international impact. This is one of the “moments” when a green criminology was “born.” Pecˇar’s work reflected emerging global interest in the green agenda, and unsurprisingly other writers in other countries also began to contribute, quite independently of each other, to such “moments” in the birth of a green criminology.

Pecˇar (1981) argued that criminology has a double role to play in the case of deviance against the environment: criminology explains the phenomena that have already been criminalized and against which the society reacts, and criminology also responds to social phenomena and events that are becoming much more important than traditionally considered. Criminology can make valuable proposals to society about appropriate reactions. From the point of view of this critical perspective, it follows that traditional criminality is not the most dangerous social deviance, because, as Kanducˇ (1992) wrote, ecological, political, and enterprise criminality are far more dangerous. A green perspective fits with a radical turn in criminology that focuses more on sociological and economic conditions and less on individuals and their characteristics.

Lynch (1990: 4) first introduced the term “green criminology” to criminological discussions as a new subfield that nonetheless, empirically and theoretically, still reflects existing traditions while fostering emergent directions. Lynch (1990: 3) acknowledged that a green criminology does not represent “an entirely new perspective or orientation within criminology” for “a number of criminologists have examined various environmental hazards and crimes,” and studies of white-collar and corporate crime have made significant contributions in this regard (South and Beirne 2006). Nonetheless, the power and utility of a green umbrella or perspective (South 1998a) lies in loosely covering or unifying the study of environmentally related harms and crimes. As examples of what might be studied, Lynch suggested a non-exhaustive list as follows:

environmental and wildlife laws and regulations;.. . the social harms associated with chemical and pesticide manufacturing on a local or global scale;.. . international treaties devoted to environmental protection; … environmental politics and power .. .; .. . unsafe working conditions and hazards created by pesticides, both in the field and in the factory; global political and economic structures responsible for the exportation of environmental hazards from industrialised, core nations to the periphery etc.; and [the] political, economic and class relationships that structure these outcomes (ibid.).

In addition, and pioneered in particular by Beirne (1995), the green criminology approach has also encompassed the increasing study of animal abuse, speciesism, and crime or harms against or involving animals (e.g., wildlife trafficking, see South and Wyatt 2011). Included here are diverse human actions that may cause suffering or death to nonhuman species or damage or destroy their habitats. For some writers, a wide range of animal welfare matters is at stake, and abuse of nonhuman species could entail physical, psychological, and/or emotional actions and harms, or indeed inaction or passive neglect (Cazaux and Beirne 2006). Varieties of environmental degradation and threat damaging to human populations (e.g., air and water pollution, soil erosion, oil spills, climate change) are, of course, also likely to be equally or even more harmful to animals and their habitats.

All this gives a sense of the subject matter content of a green criminology, but what of the conceptual approach that characterizes green criminology? Eman et al. (2009) have written of the development of green criminology research in Slovenia and South-Eastern Europe, noting along the way the challenges of definition and theory that arise. Thus, they observe “Different irregularities, indecencies, violations and crimes against nature are addressed among … criminologists as green crimes” (2009: 581) but then note that it has been hard to identify or develop a single theoretical approach in this area.

The theoretical frame of green criminology is hard to define. White (2008: 14) is clear and brief: “There is no green criminological theory as such.” Closest to [a] theory is South (1998a: 212), although he talks only about the perspective or ecological viewpoints and not about theory. .. . Clear definitions are rarely presented making successful research into green crimes more difficult. Halsey (2004) criticises green criminology because of its lack of a (suitable) definition and challenges criminologists to reduce ambiguity with a clear definition of green criminology (Eman et al. 2009: 581, footnote 9).

In her Presidential speech to the American Society of Criminology in 1998, Zahn (1999) wrote of the far-reaching impacts of pollution and biodiversity loss and indicated that in the future she expected to see more criminological focus on environmental crime, this in turn would bring “a new definition of victims to include species other than humans and a definition of offenders to include those who pollute for convenience … [and] for profit.” Importantly, Zahn observed that “Just as Sutherland’s white-collar crime expanded our crime paradigm (1949), … environmental crime will change it in the future.” (Zahn 1999). South’s (1998b: 445–453) typology reflects both new directions as well as classic core concerns in criminology such as breaching laws, making laws, and reactions to law-breaking and law bending. Thus South proposed three foundations for a green criminology:

- Studies of breaches of regulations, disasters, and corporate and state violations

The themes of the relevant literature here concern (a) the study of regulation, for example, the positive and negative features, and the consequences, of different regulatory models; (b) pollution, disasters, and liabilities as “single-event” case studies; and (c) corporate and state misconduct or crimes which have environmental consequences, with the focus bearing on the perpetrators, culpability, and the nature of serial offending.

- Legal frameworks, criminalization, and “shaming”

Is concerned with the legal issues raised by environmentally damaging acts and how these should be classified (violations? crimes?) and responded to (by regulation? criminalization? Inspectorates? police?). Such cases may be difficult to prosecute because of lack of evidence and proof, blurring of the lines between the “willful criminal violator” and the “legal risk-taking entrepreneur,” and/or corruption in the system. The problem of how to respond to such offenses in an effective legal manner through criminalization has been subject to debate and has embraced arguments against criminalization as well as powerful arguments in favor. Even if a prosecution is brought and is successful, penalties are usually modest relative to the damage done: if the corporation is fined, it will absorb such costs and/or simply pass them onto consumers. Attempts to identify and sanction key, responsible individuals have had only rare success and alternatives such as Braithwaite’s (1989) notion of “shaming,” and approaches based on principles of restorative justice seem promising based on the proposition that corporate image is a more vulnerable target for censure and sanctions than corporate assets and that “making good” may be more beneficial than imposing immaterial fines or trying to identify a “culprit” to receive a prison sentence.

- Social movements, “green politics,” and policy futures

Numerous political and pressure groups debate, champion, question, and dispute matters related to the environment. These include anti-environmentalist organizations supported by corporate and state interests and proenvironment groups which may be extreme (e.g., employing terrorism) or controversial (championing animal rights as more important than human rights), as well as those engaging in “new social movements” and alternative lifestyles, or those of the middle-range political left, center, and right who support campaigns to “protect and preserve” and resist construction development projects. The importance of the feminist critique of masculine violence against the environment and, in the USA, the emergence of networks of black activists working against environmental damage to their communities (Bullard 1990) are expressions of protest that should also be noted.

Most “green” criminologists would probably agree that it is now quite clear what kind of subject matter is relevant but might also debate whether it would be possible or even desirable to attempt to impose a single theoretical proposition or framework on this area of work. There is therefore some variety in the positions outlined in the literature. Lynch and Stretesky (2007) refer to an eco-critical criminology as a contrast with the more familiar critical criminological approach that excludes nonhuman nature from its analysis and also (Lynch and Stretesky 2003: 218) “take the view that green crimes, like other crimes, are social constructions influenced by social locations and power relations in society.” White (2003: 484) takes this point further, arguing that:

investigating environmental issues from a criminological perspective requires an appreciation of how harm is socially and historically constructed. In turn this necessitates understanding and interpreting the structure of a globalising world; the direction(s) in which this world is heading; and how diverse groups’ experiences are shaped by wider social, political and economic processes. Thus this area of criminology is at once basic and exceedingly complex.

More recently, White (2010: 6) refers to ecoglobal criminology as a framework or paradigm within criminology “that is informed by ecological considerations and by a critical analysis that is worldwide in its scale and perspective.” The research agenda of an ecoglobal multidisciplinary approach can be used for the study of environmental harm. Furthermore, ecoglobal criminology defines different forms of environmental harm as “criminal,” though they may not be considered illegal in conventional terms.

Herbig and Joubert (2006) have proposed the idea of a conservation criminology. Conservation criminology is concerned with environmental protection, adopting interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research approaches to understanding environmental criminality, environmental threats, and related risks. This approach therefore offers the integration of criminology with natural resource disciplines, other social science fields, and risk and decision sciences. It encourages the examination of political, cultural, economic, and social influences on the definition of environmental crime. The parameters of conservation crimes can be seen as falling within existing and commonly used crime categories such as white-collar crime, organized crime, invisible crime, and property (economic) crime. Gibbs and colleagues (2010: 125–126) concur with Herbig and Joubert (2006) that conservation criminology identifies core themes in the environmental field of study and suggest that the focus of conservation criminology begins with assessment and study of environmental risks at the nexus between humans and natural resources that involve issues of crime, compliance, and social control (Gibbs et al. 2010: 128). Conservation criminology encompasses the study of wildlife, pollution, human populations, and other areas often considered to be mutually exclusive.

State Of The Art

A green perspective in criminology offers an open framework rather than ties to a closed theory and lends itself well to interdisciplinary insights and collaborations. Research covers subjects such as environmental crimes and criminality, harm and victimization, legislation and regulations, protection measures, and public responses to violations. Green criminology is much more than just a discussion about environmental issues and reflects a critical criminological position on the need to defend the environment and to uphold the rights and safety of both humans and nonhuman species. The research agenda for green criminology is based on the objective of studying known forms (and uncovering unknown forms) of deviant and criminal behavior committed against the natural environment and those living beings dependent upon it.

Environmental crime is a now widespread problem across modern societies and may be defined as crime in formal terms where temporary or permanent acts or activities damaging the environment and species are determined and defined as criminal by (inter)national legislation. However, there are numerous forms of harm which lie outside the formal labels of judicially defined offenses but which have immediate or long-term consequences of a nature harmful or prejudicial to well-being, health, safety, and life. For example, artificial changes, degeneration, or destruction affecting air, water, soil, mineral materials, plant species, bacteria, and viruses can harm the natural environment or interrupt its natural changes with consequent and interactive impacts on human and animal species. These latter events may not be defined technically as crimes but are serious in their harmful outcomes and for this reason are considered within the framework of a green criminology. In any of these cases, the violator could be any or every one of us (corporations, companies, groups, individuals, etc.). Environmental crimes have multiple victims because besides, or directly through, the affected environment (biotic and abiotic natural elements), human and other species are harmed as well. However, as with many other forms of deviance and damage, not all are legally defined as crime but are nonetheless viewed as significant harms deserving censure, control, and remedy.

Basic human conditions for existence are essential and include air, water, and fertile soil. For a green critical criminology, it is obvious that these are resources to which all must have access and that fall within the notion of universal rights. Denial of such access represents the point of conflict between environmental rights and property rights. In this critical view, both the wealthiest individuals (or members of the wealthiest social class) and the wealthiest nations are guilty of overconsumption of natural resources and hence are the most significant contributors to environmental degradation and ultimately the impoverishment of other people and the planet. A rights-based approach to addressing such inequalities is complex but at the least might promote a substantive right to a healthy and pollution-free environment.

Climate change is expected to be a significant criminogenic force in future decades creating shortages of food and water that may lead to illegal markets and conflicts. In times and locations of impoverishment, human populations are more ready to exploit the resources of the natural world without regard for consequences and conservation, and they may also be more likely to move to other places that are known or believed to be more abundantly resourced. Both voluntary or forced migration and displacement can provide solutions but also simply lead to the reproduction of the original circumstances as money, labor market opportunities, or other resources prove to be unavailable. New cycles of vulnerability, victimization, offending, and perhaps yet further migration can be set in motion (South 2010; White 2008).

As well as having a criminological foundation, work in this area arises from socio-legal studies and environmental law (see, e.g., Farrall et al. 2012). However, Stallworthy (2008: 4–5) has argued that “.. .there can be a sense that environmental law discourse is ultimately shackled by a dependent, satellite status, a repository of greener values, but for the most part swimming against a distinctively ungreen tide of prevailing legal priorities.” Obviously, this is not the end of the matter, and there can be few other areas of law with such a claim to significance for the future of the planet and its inhabitants. There is considerable scope to broaden legal discourse to incorporate “long unasked questions as to the ecosystem and biodiversity protection, as well as appropriate conditions for access and use of natural resources” (ibid: 3). This “broadening of the discourse” is undoubtedly happening. Today, international environmental policy is at the forefront of many progressive developments prefiguring more general trends in public international law. For more than a century, nation-states have adopted international environmental instruments that aim to have the force of law. They are of various types: global, multilateral, regional, and bilateral treaties; court-made and customary law; and soft law; and vary in the extent to which they affect national sovereignty and establish jurisdiction (DiMento 2003: 56). International environmental protection law is constantly changing with the high number of accepted international legal instruments (about 300 at the end of 2010) clearly pointing to the seriousness of the problem of violations of environmental protection. Attempts at meetings (in Rio de Janeiro, The Hague, Nairobi, Stockholm, Montreal, Kyoto, Buenos Aires, Johannesburg, and Copenhagen) to construct an international law of the environment have witnessed an intense and active but often confusing drama. DiMento (2003) questions whether these sessions, involving very different voices from high state representatives to indigenous people to NGOs and observers, can actually produce commonly agreed and understood effective law.

Methodologically, both qualitative and quantitative social science methods are appropriate and employed. Croall (2011: 360) notes that “as for corporate crime, there is no centralized source of information about environmental crime, and a wide range of sources, most from outside criminology, have to be used. Offences rarely appear in victim surveys, not being considered as ‘criminal’, and often being invisible. Like corporate or state crime, research is further hampered by difficulties of access and obtaining information, much of it regarded as confidential, as it is not widely regarded as part of the criminological agenda, funding tends to be scarce.” Nonetheless, research in some areas such as environmental justice and environmental victimology does lend itself to survey methods but also to sensitive interview methods and to investigative data gathering, analyzing news coverage, or scientific reports, for example. In this respect, some green criminology studies lie close to epidemiological public health research and support the development and use of science in the interests of those who are victimized but frequently excluded from recourse to redress or protest. The victimized are paradoxically often excluded from debates and decisions most affecting them because greater economic power can mobilize expert opinion and promote particular positions. A green criminology can play an advocacy role using science and data on behalf of the victimized to tell the stories otherwise ignored. It is also felt that the use of a comparative approach and methods should be particularly fruitful and informative within green criminology. The use of comparative methods in criminology and criminal justice studies is necessary to ascertain social, cultural, political, economic, and other impacts on any differences in patterns of offending and attitudes towards environmental crime, in environmental protection laws, and in law enforcement responses to the violation of laws. For this reason, comparative studies should be more frequently used in comparing forms of environmental crime and environmental justice responses between two or more countries. However, it will always remain true that the identification of the particularities and specifics of each country must not be ignored and may require separate treatment. Heckenberg and White have provided valuable overviews of research methodology appropriate to this field and argue that the different dimensions of environmental harm need to be broken down as these “pose particular challenges for researchers insofar as different types of knowledge are required for dealing with specific kinds of environmental harm. Moreover, analysis needs to take into account considerable diversity in terms of: Who the victim is (human or non-human); Where the harm is manifest (local through to global); Main site where the harm is apparent (built or natural environment)” (Heckenberg and White 2013). The authors also advocate the compilation of data from across a wide range of possible and available sources, international, interdisciplinary, and cross-culturally, as the basis for analysis of contemporary issues but also for purposes of extrapolation and horizon scanning to identify future challenges and crises.

Key Controversies And Open Questions

At present, it seems that late-modern societies remain set on a path of continuing behavior seriously detrimental to the environment and, according to some commentators, worthy of description as “ecocide” and requiring legally recognized instruments of protection and response (Higgins 2010; South 2010). Social and economic conflicts arising from resource scarcity or exploitation, as well as climate change phenomena, present major challenges for human rights, civil society, and species preservation in many parts of the world. Climate change will be both criminogenic and a stimulus to control and security measures. The global flow of people and goods is intimately bound up with impact on the environment, and there is scope for protest, both peaceful and violent, about, for example, unnecessary transport, production of waste, and inequalities in access to food. Future conflicts and crimes may increasingly center on environmental resources, with global warming and accumulating resource poverty raising the temperature of existing tensions and accelerating processes of exploitation, whether between social classes, different ethnic groups, or regions and states competing for or claiming ownership of resources. Conflict and crime are likely to follow if legally sanctioned, but politically unpopular – as well as illegal – migration is stimulated by climate change-induced impacts on living conditions and the sustainability of agriculture, water availability, or other vulnerable systems. In such circumstances, the balance of rights such as freedom of movement versus measures that impose restrictions on mobility will come under scrutiny, and nationalist politics and national security preoccupations could lead to the creation of labels of “criminal” and “unwelcome threat” applied to those who should be seen as “victims” and “refugees.”

Future Directions

The extension of this work in countries which have similar or very different profiles emphasizes one of the fundamental requirements for a future global green criminology – a program of comparative work. A research program to help reduce environmentally damaging activities and hence consequences could form the basis for a prospectus for green–crime-prevention research as well as propositions for remedial actions and responsive policies. In all of this, it has to be recognized that variations in definitions of offenses and differences of approach between jurisdictions mean that not only is enforcement hampered but data gathering and comparison are difficult – a further reason why we need comparative work and some harmonization of understanding and approach in areas of law and enforcement. Environmental issues affect different countries in different ways. Creating and enforcing national and international laws can be a very difficult process (Michalowski 1998: 328), particularly when dealing with environmental destruction and degradation issues. Environmental crime has no regard for national borders, so such problems often cannot be solved within the scope of national powers or policies. In cases such as safeguarding of international waters, seas, and air, or international transport by planes (noise and emissions), or transportation of hazardous materials and waste, or destruction of forests (acid rain), then interstate or international law is necessary. Such transnational action should lead to the determination of (international) standards which support the objectives of achieving environmental protection, and relevant research will be required (Mesˇko et al. 2011).

Increasing efforts to regulate and control could create new forms of criminal offense or at the least widen the embrace of those found guilty of breaches of expectations, rules, or local laws. Insofar as this is part of a process generally set in train to protect the common interest and defend victims of uncontrolled and irresponsible actions, the principles are not dissimilar to the traditional operation of criminal justice; however, as much that needs to be regulated or curtailed is currently acceptable and legal behavior, then new groups of offenders and victims may be created. This may occur in relation to, for example, controls to mitigate climate change or requirements to conserve energy or water. This set of circumstances will create a set of issues for future research.

As criminality changes through time, so does criminology. The discovery of patterns of environmental crime in any region and the sharing of findings about similar green issues will enable cooperation between countries and support their responses to environmental issues.

Conclusion

In the twenty-first century, a relevant criminology needs to be aware of the meaning of the environment for the survival of the planet and its inhabitants (South 1998a; Eman et al. 2009: 581), and therefore, its intellectual breadth must accommodate crimes and harms relating to the interdependencies between environments, humans, and animals. Human beings share the planet with other animals, plants, and living beings (such as microorganisms and microbes) in a natural cycle, without which it would be impossible to survive (Eman et al. 2009: 581). The development of a green (or ecoglobal or conservation) criminology as a perspective or approach has been a product of a period when environmental issues have become more prominent on public and political as well as scientific agendas. Such a new direction in criminology has emerged independently in different countries but with a broadly shared and similar main objective – to study and critique crimes and harms against the environment on a regional, national, or global level. As this green field grows, one of its main strengths is the increasing international joining together and networking of these various branches.

Bibliography:

- Beirne P (1995) The use and abuse of animals in criminology: a brief history and current review. Soc Justice 22:5–31

- Beirne P (2009) Confronting animal abuse: law, criminology, and human-animal relationship. Rowman & Littlefield Publisher, Maryland

- Beirne P, South N (1998) Editor’s introduction. Theor Criminol 2:147–148

- Beirne P, South N (2007) Issues in green criminology: confronting harms against environments, humanity and other animals. Willan Publishing, Portland

- Braithwaite J (1989) Crime, shame and reintegration. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Bullard R (1990) Dumping in Dixie: race, class and environmental quality. Westview Press, Boulder

- Cazaux G, Beirne P (2006) Animal abuse. In: McLaughlin E, Mucie J (eds) The Sage dictionary of criminology. Sage, London

- Clifford M (1998) Environmental crime: enforcement, policy, and social responsibility. Aspen Publisher, Gaithersburg

- Croall H (2011) Crime and society in Britain. (2nd edn), Harlow: Longman Pearson

- DiMento JF (2003) The global environmental and international law. University of Texas, Austin

- Ellefson R, Larsen G, Sollund R (2012) Eco-global crimes: contemporary ad future challenges. Ashgate, Farnham

- Eman K, Mesˇko G (2009) Ekolosˇka kriminologija – poskus opredelitve in razprava. Varstvoslovje 11:357–381

- Eman K, Mesˇko G, Fields CB (2009) Crimes against the environment: green criminology and research challenges in Slovenia. Varstvoslovje 11:574–592

- Farrall S, French D, Ahmed T (2012) Climate change: legal and criminological implications. Hart, Oxford

- Gibbs C, Gore ML, McGarrell EF, Rivers L (2010) Introducing conservation criminology: towards interdisciplinary scholarship on environmental crimes and risks. Br J Criminol 50:124–144

- Halsey M (2004) Against ‘green’ criminology. Br J Criminol 44:833–853

- Halsey M, White RD (1998) Crime, ecophilosophy and environmental harm. Theor Criminol 2:345–371

- Heckenberg D, White R (2013) Innovative approaches to researching environmental crime. In: South N, Brisman A (eds) The international handbook of green criminology. Routledge, London

- Herbig FJ, Joubert SJ (2006) Criminological semantics: conservation criminology – vision or vagary? Acta Criminol 19:88–103

- Higgins P (2010) Eradicating ecocide: laws and governance to prevent the destruction of our planet. Shepheard-Walwyn, London

- Kanducˇ Z (1992) Radikalna kriminologija – kriminologija vsakdanjega zˇivljenja. Revija za kriminalistiko in kriminologijo 43:103–115

- Koser Wilson N (1999) Eco-critical criminology – an introduction. Crim Justice Policy Rev 10:155–160

- Lynch M (1990) The greening of criminology: a perspective for the 1990’s. Crit Criminol 2:11–12

- Lynch ML, Stretesky P (2007) Green criminology in the United States. In: Beirne P, South N (eds) Issues in green criminology: confronting harms against environments, humanity and other animals. Willan Publishing, Portland

- Lynch MJ, Stretesky PB (2003) The meaning of green: contrasting criminological perspectives. Theoretical Criminology 7(2):217–38

- Mesˇko G, Dimitrijevic´ D, Fields CB (2011) Understanding and managing threats to the environment in South Eastern Europe. Springer, Dordrecht

- Michalowski R (1998) International environmental issues. In: Clifford M (ed) Environmental crime: enforcement, policy, and social responsibility. Aspen Publisher, Gaithersburg

- Pecˇar J (1981) Ekolosˇka kriminaliteta in kriminologija. Revija za kriminalistiko in kriminologijo 34:33–45

- Rock P (1994) History of criminology. Dartmouth: Aldershot

- South N (1998a) A green field for criminology?: a proposal for a perspective. Theor Criminol 2:211–233

- South N (1998b) Corporate and state crimes against the environment: foundations for a green perspective in European criminology. In: Ruggiero V, South N, Taylor I (eds) The new European criminology. Routledge, London/New York

- South N (2010) The ecocidal tendencies of late modernity: trans-national crime, social exclusion, victims and rights. In: White R (ed) Global environmental harm: criminological perspectives. Willan Publishing, Cullompton

- South N, Beirne P (2006) Green criminology. Dartmouth, Aldershot/Brookfield

- South N, Wyatt T (2011) Comparing illicit trades in wildlife and drugs: an exploratory study. Deviant Behav 32:1–24

- Stallworthy M (2008) Understanding environmental law. Sweet & Maxwell, London

- White RD (2003) Environmental issues and the criminological imagination. Theor Criminol 7:483–506

- White RD (2008) Crimes against nature: environmental criminology and ecological justice. Willan Publishing, Cullompton

- White RD (2010) Prosecution and sentencing in relation to environmental crime: recent socio-legal developments. Crime Law Soc Changes 53:365–381

- White RD (2011) Transnational environmental crime. Willan Publishing, Cullompton

- Zahn M (1999) Presidential address – thoughts on the future of criminology. Criminology 37:1–16

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.