This sample History of Randomized Controlled Experiments in Criminal Justice Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

This research paper examines the history of randomized controlled experiments in criminology and criminal justice. First, fundamental characteristics of randomized controlled experiments are briefly described, emphasizing the connection between this research method and evidence-based crime policy. Then, historical trends of experiments in criminal justice are reviewed, highlighting David Farrington’s work in this area. The authors continue by connecting the history of experiments as well as their characteristics and the debates surrounding their use in the context of the evidence-based crime policy movement. Specifically, the authors suggest that the history of experiments in criminal justice and their relative rarity compared to other evaluation research cannot be divorced from the broader discussions and realities about the “what works” movement in criminal justice. Finally, this research paper provides thoughts about the future of experiments in criminal justice and the research infrastructure being built to support them.

Fundamentals Of Randomized Controlled Experiments

A randomized controlled experiment is a research method used to examine the effect that a treatment, program, intervention, or condition has on a particular outcome. In criminology, experimental methods are used to examine whether a crime policy or law, an offender treatment, a crime prevention program, or a new organizational process can reduce or prevent crime, lower recidivism, or temper fear of crime. Experiments can also be used to examine the impact that interventions have on legal processes and justice externalities, including differential treatment, legitimacy, employee job satisfaction, or corruption of justice agents. Although the terms randomized controlled experiment and randomized controlled trial are often used interchangeably, a trial implies the implementation of the experimental design.

Experiments are differentiated from other evaluation methods, such as “quasi-experiments” and before-after designs, because the treatment or condition is randomly allocated to some subjects (persons, places, situations, etc.) and not others. By randomly allocating an intervention to control and treatment groups, a researcher can ensure that no systematic bias contributes to group differences before or after an intervention is applied (Campbell and Stanley 1963). Specifically, random allocation allows for the assumption of equivalence between treatment and comparison groups, which allows the researcher to rule out confounding factors that might explain differences between groups after treatment (Weisburd 2003). By randomly allocating treatment, an appropriate counterfactual is developed in the control group, which shows what would happen if a program or treatment was not administered (Cook 2003).

Randomized controlled experiments have been called – not without debate – the “gold standard” of evaluation research, as it is seen as one of the best ways that evaluators can maximize a study’s internal validity, thereby generating findings that are believable (Boruch et al. 2000a; Farrington 2003a; Weisburd 2000). Internal validity refers to an evaluator’s ability to determine whether the intervention – as opposed to other effects – caused a change in the outcome measured (Shadish et al. 2002). This determination is also facilitated by good design and fidelity of implementation of the experiment. However, the label of “gold standard” relies on its strength in establishing internal, rather than external validity, a weakness of randomized controlled designs. Other criticisms are presented in more detail below.

Historical Trends In Experimental Criminology

Farrington (1983) and Farrington and Welsh (2006) have examined the history of the use of randomized controlled experiments (RCEs) in criminal justice and criminology in detail, and we summarize their efforts here. As they describe, the use of RCEs in criminology has focused on crime prevention and delinquency treatment programs, whose beginnings are marked by the Powers and Witmer (1951) Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study. This program was initiated by Richard Cabot in 1939 and involved over 500 delinquent boys, half of whom were randomly assigned to a treatment group and the other half to a control group. The Cambridge-Somerville Youth study is widely considered one of the earliest and most influential experiments in criminal justice research (Weisburd and Petrosino 2004). This experiment and McCord’s (1978) follow-up research found that the treatment may have backfired, causing the boys who received the treatment to commit more crimes and have a lower quality of life.

After the Cambridge-Somerville Youth study, early experimentation in criminal justice did not necessarily show optimistic results, and many foundational experiments and reviews created a pessimistic environment for criminal justice interventions. Using a threshold of 100 or more subjects, Farrington (1983) identified 37 experiments in criminal justice in the first 25 years of this history (1957–1982), many of which did not show positive effects. The four policing experiments he reviewed focused on juvenile diversion schemes, two of which reported positive results of youth diversion programs and two reporting backfire effects of the programs. Six crime prevention experimental evaluations were also not optimistic (which included the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study and its follow-ups). It appears the only experiment with significant positive findings in this crime prevention group was the one conducted by Maynard (1980), which examined the effects of a multi-site community-based intervention operated by the Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation. In that study, highly structured work experiences and job placement led to significantly lower arrest rates in the treatment than control group, but only in the short term.

Farrington (1983) also found 12 correctional experiments satisfying his criteria, focusing primarily on counseling offenders. Only three resulted in significant reductions in offending. Three court-related experiments were also discovered, with only one showing reductions of truancy by bringing children to court and using adjournments (delaying supervision by social workers) versus immediately assigning them to supervision. The authors concluded that the effect may have been caused by the type of worker handling adjournment versus supervision, the former more likely to be concerned with reduction of truancy than the latter. And finally, Farrington (1983) reports the results of 12 community-oriented interventions evaluated with experimental methods. Only one, he discovered, could be said to show significant reductions in offending.

An updated review conducted by Farrington and Welsh in 2006 proved more positive. They found 85 additional experiments between 1982 and 2004, many showing positive effects of the interventions studied. With regard to policing, the updated review reported 12 experiments, largely focusing on the area of domestic violence and repeat offenders, but some experimenting on police interventions at places. Of these 12 studies, six reported significant effects in the intervention reducing recidivism and crime. The place-based experiments were an innovation in the history of experimentation, which previously was focused on individuals. The Minneapolis Hot Spots Experiment (Sherman and Weisburd 1995) was significant in this regard, which was then followed by numerous place-based experiments in criminology. Overall, the policing research in Farrington and Welsh’s new review had a more optimistic outlook, showing that police can indeed prevent crime among people and places.

Prevention experiments also grew from six in Farrington’s first review to 14 in the updated review. Of the 14, six showed that interventions had significant positive effects, and some of the interventions have been highly influential in the discipline. In particular, the work of Olds and his colleagues (1998) on home visitation nurses showed that non-visited mothers tended to abuse and neglect their children more. His work, which subsequently contributed to his receipt of the Stockholm Prize, led to a movement for improvement in postnatal care using home visitation. Other developmental experiments involving sending kids to preschool, early child and parent skills training, multi-systemic therapy (as opposed to supervision and probation), and employment services showed positive effects. Unlike the vague counseling strategies covered in Farrington’s earlier review, these promising interventions were more specific, targeted, and focused on developmental stages.

Farrington and Welsh also included 14 correctional experiments with interesting findings that challenged widely held beliefs. In particular, popular interventions like scared straight and juvenile boot camps showed backfire or nonsignificant effects on juvenile delinquency, while therapeutic communities, drug treatment, and cognitive behavior therapy proved promising (see also MacKenzie’s review in 2002). Farrington and Welsh also located 22 court-based experiments, such as court-mandated treatment, restitution, intensive supervised probation, restorative conferences, and pretrial methods. Like corrections studies, many of these studies and their replications helped show that a number of traditional criminal justice programs were not as effective as initially believed (again, we point the reader to Farrington and Welsh 2006, for detailed discussions of these experiments).

Finally, Farrington and Welsh also found more community-based experiments (23 studies) than Farrington’s initial review, which offered mixed results, especially in the area of intensive supervised probation. Petersilia and Turner (1993) found that, in some cases, community-based supervision led to increased offending, while in others, it led to decreased recidivism. This was highly connected to the reporting of probation violations and revocations, not necessarily to the frequency of crime commission, which is a much harder aspect to measure. MacKenzie’s (2002) assessment of the corrections experiments was more nuanced, given these mixed findings. It appears that more tailored and structured community supervision programs that involve the right therapy, treatment, and employment opportunities can have an effect on recidivism, even if intensive supervised probation alone may not be able to do this. On the other hand, experiments in the corrections and community area have also shown that shock probation, scared straight, unstructured and vague rehabilitation programs, correctional boot camps, urine testing, community residential programs, and juvenile wilderness programs are not effective (MacKenzie 2002).

Randomized Experiments And The Evidence-Based Crime Policy Movement

The reviews by Farrington, Welsh, and MacKenzie show a general growth in experimental research since the 1950s and more optimistic findings about specific crime and justice relevant interventions. However, the history of experimental criminology is still a “meager feast” (Farrington 2003b) centered on American criminology (Farrington and Welsh 2006). Despite its gold standard label, the use of experiments has been relatively rare compared to other methods used in evaluating interventions (Weisburd 2003). Indeed, Farrington and Welsh (2006) still only discovered 122 experiments between 1957 and 2004, compared to the many more hundreds of evaluations conducted using other methods.

Others have also confirmed this finding of a dearth of experiments (see Boruch et al. 2000a; Palmer and Petrosino 2003; Petrosino et al. 2003; Sherman et al. 1997, 2002). Lum and Yang (2005), in a review of Sherman and colleagues’ (2002) updated review of 657 evaluations of criminal justice programs, found that experiments accounted for 16 % (n ¼ 102) of the evaluations reviewed. In contrast, the vast majority of studies in Sherman’s updated review used before-after designs or compared non-comparable groups with and without treatment. Baird’s (2011) review of the population of all 1,025 articles published in our field’s leading journal, Criminology, from 1980 through August 2011, reveals only 14 articles (1.4 %) that used an experimental design. Moreover, Baird’s (2011) review of the 14 experimental studies published in Criminology finds that even for those published in our leading journal,

…the descriptive validity of statistical power in many of the studies was low. Six of the studies did not report they were experimental in their title. Five studies did not report enough information to conduct power analysis. Errors such as failing to report directional hypotheses, sample sizes of groups, and alpha levels are critical omissions. For those studies that did provide enough information to calculate power, the power levels were generally high for large and moderate effects and were generally low for small effects. (2011, p. 15)

There have been numerous reasons given for the scarcity of experimental research in criminology and social science, and practical and ethical concerns are cited most often (see Boruch et al. 2000b; Clarke and Cornish 1972; Cook 2003; Farrington 1983; Lum and Yang 2005; Petersilia 1989; Shepherd 2003; Weisburd 2000). Some also believe that using experiments is challenging when studying the complexities of social relationships and issues (Burtless 1995; Clarke and Cornish 1972; Heckman and Smith 1995; Pawson and Tilley 1997), or that it is difficult for experiments to maintain high fidelity when implemented (Berk 2005). Lum and Yang (2005) also found, when surveying researchers about their choices to use or not use experimentation, that the lack of funding was often more a concern than ethical or even practical reasons. Indeed, Palmer and Petrosino (2003), when examining the history of the California Youth Authority (CYA), found that when funding switched from the experimentation-friendly National Institute of Mental Health to the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, which rarely funded such studies, the focus of the CYA also moved away from experiments.

The practical, ethical, and funding challenges of randomized controlled experiments do not exist in a vacuum; they are also influenced by the context of the role and history of experimental evaluation in crime prevention more generally. In particular, the low proportion of experimentation may be a result (or symptom) of the messy quest for understanding and implementing “what works” in criminal justice, or the “evidence-based crime policy” movement. In general, this movement suggests that criminal justice practice should be guided by the best available research and analysis about interventions (Sherman 1998; Sherman et al. 2002), rather than by anecdote, feelings, habit, or opinions about best practices (Lum 2009). However, the goal to translate and use research in practice requires a keen sensitivity to practicality, ethicality, and costs. These core values of evidence-based crime policy can be, as previously mentioned, challenges to experimental criminology. Thus, while the demand for knowledge about effective interventions in the evidence-based crime policy movement certainly encourages more use of high quality evaluation designs, other core values can also work against that effort.

Two discussions may better illustrate the ironically difficult relationship between experiments and the evidence-based crime policy movement. The first involves the story of the Martinson Report (See Lipton et al. 1975; Martinson 1974) and the subsequent University of Maryland Report to Congress (Sherman et al. 1997, 2002). In 1975, Lipton, Martinson, and Wilks published a review of 231 evaluations of rehabilitative programs, to which Martinson publicly asserted that such programs had “no appreciable effect on recidivism” (Martinson 1974, p. 25). As described by Pratt et al. (2011), the report, which became known as the “Martinson Report,” may have been one reason (in the context of rising crime rates and changing social cultures) for the decline of the rehabilitative ideal. At the same time, however, this shift from rehabilitation to punishment and the pessimistic assertions by Martinson arguably sparked the modern-day, evidence-based crime policy movement. Not only did evaluators wish to find what did work for rehabilitation and corrections, but they also wanted to increase the believability of such studies by using stronger evaluation methods (i.e., experiments). As Doris MacKenzie (2008) stated in a keynote address, an evidence-based approach to crime prevention “rejects the nothing works philosophy and instead examines what works to change criminal and delinquent activities. It is a belief that science can be used to inform public policy decisions about which programs or interventions should be used to change offenders.”

Sherman and colleagues’ (1997) University of Maryland Report to Congress, and the update to this report (Sherman et al. 2002) could arguably be viewed as an attempt to challenge the consequences of the Martinson Report. Not only did they take into account the many new evaluation studies generated between 1974 and 2002, but they also weighed and ranked the methods used in those evaluations to make judgments about how much we should believe specific study findings. Developing a Scientific Methods Scale (SMS), they rated studies in criminal justice according to the following scheme:

- Correlation between a crime prevention program and a measure of crime or crime risk factors

- Temporal sequence between the program and the crime or risk outcome clearly observed, or a comparison group present without demonstrated comparability to the treatment group

- A comparison between two or more units of analysis, one with and one without the program

- Comparison between multiple units with and without the program, controlling for other factors, or a nonequivalent comparison group has only minor differences evident

- Random assignment and analysis of comparable units to program and comparison groups (Sherman et al. 1997)

Sherman and colleagues’ methodological ratings were purposeful. The ratings implied that not all research could be considered equal. Conclusions of methodologically stronger studies were arguably more reliable than weaker ones in their assertions about “what works, what doesn’t and what’s promising” (the title of the report) in crime prevention interventions. The SMS scoring system solidified the importance of randomized controlled experiments in this endeavor, which were rated with the highest score of “5.” Rating the believability (and usability) of evaluations in a document intended to influence criminal justice practices arguably helped to link experimental criminology with evidence-based crime policy more generally.

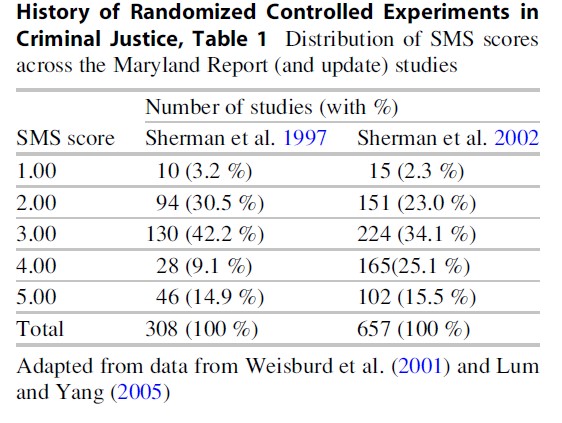

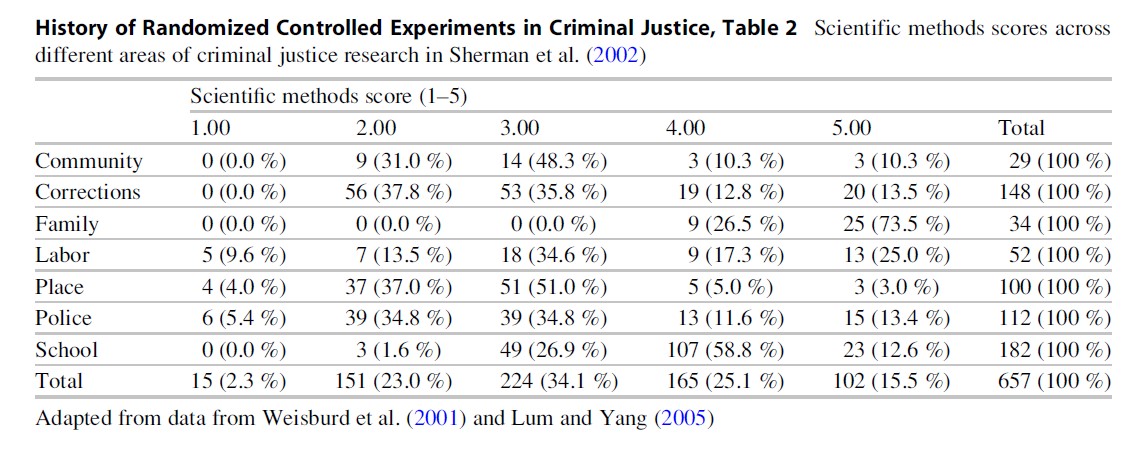

Given that the Maryland Report and the SMS ratings became part of the more general evidence-based crime policy movement, what has been its connection to the history of experiments in criminal justice? Analysis using the SMS ratings of studies may prove helpful in better understanding this complex relationship between experimental criminology and evidence-based crime policy. Weisburd et al. (2001) and Lum and Yang (2005) have studied the evaluations chosen by Sherman et al. (1997) and Sherman et al. (2002). Using their data, we present Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 shows that despite the increase of evaluations between 1997 and 2002, the proportion of evaluations using experiments remains consistently low. Of the 308 and 657 studies in Sherman et al. (1997) and Sherman et al. (2002), respectively, only 15–16 % of the studies employed a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of interventions. Interestingly, there was an increase in the number of quasi-experimental studies in criminal justice between the 1997 report and the 2002 update (from 9 % to 25 %), and a decline in the proportion of lower quality studies (SMS = 1, 2 or 3). While this shows a general improvement in the state of criminal justice evaluation research, the proportion of experiments have remained the same.

Further, as Table 2 shows, the use of RCEs varies across different sectors of criminal justice research. Using the studies in Sherman et al.’s (2002) review, we find experimentation is more common in interventions related to family or employment arenas than in policing and corrections, two of the largest justice institutions.

Thus, while evaluation research has increased generally in criminal justice, and while the evidence-based crime policy movement arguably gained momentum between 1997 and 2002, the proportion of experiments generally, and within two large areas of criminal justice, remain consistently low. Further analysis of the initial Maryland Report by Weisburd et al. (2001) also revealed another relationship between experiments and evidence-based crime policy. They discovered an inverse relationship between study findings and research design. At least in the crime and justice evaluation arena, it appears that studies that employ more rigorous methodological designs (i.e., experiments) are more likely to find that interventions are not effective, or even may create “backfire” or harmful effects (McCord 2003). Their analysis emphasized the practical (and perhaps ethical) importance of using the best methods available when evaluating interventions to achieve the goals of evidence-based crime policy. Specifically, conclusions about “what works” based on less rigorous evaluations may lead to false optimism about the effectiveness of interventions in reducing crime and recidivism. This in turn might lead to bad decisions based on such research, clearly not a goal of the evidence-based crime policy movement. At the same time, this might also explain why experiments aren’t used as often-findings are often less optimistic when researchers use this method.

The SMS ratings about research quality also raised important debates and questions about whether experiments should be rated so highly and have such a major influence on policy (see discussions by Hough 2010; Pawson and Tilley 1997). Although ranking experiments as the highest quality evaluation method available recognizes their scientific value, such rankings also make value judgments about the types of research that should be used to influence policy. The evidence-based crime policy movement not only emphasizes using good science (such as RCEs), but also the translation of that science into practice (Lum 2009; Lum et al. 2012). Some have argued these two goals may conflict with each other. In particular, Berk (2005) points out the difficulty in maintaining the fidelity of implementation in experimenting on justice interventions and the consequences for using results in practice (see also Petersilia 1989). Pawson and Tilley (1997) have discussed how experiments may not take into account the realities of interventions and their contexts and, therefore, may not always be the most optimal way of evaluating programs. Further questions have emerged in this debate: What should be the methodological threshold by which evaluation research could be used to inform policy? Are experiments the “best” way to guide policy and practice? The reviews of the research and the rating of studies have brought forth these questions and show that the pursuit of experiments within the evidence-based crime policy movement is complicated.

A second discussion that may further illustrate how the history of randomized controlled trials is entangled in the evidence-based crime policy movement involves policing evaluations within this broader movement. Starting with the early experiments in Kansas City (Kelling et al. 1974), Newark (Police Foundation 1981), and Minneapolis (Sherman and Berk 1984), evaluation research on police crime control interventions has accumulated over the last four decades. These evaluations – too numerous to list here – run the range of police crime control and prevention efforts, and use many different types of research methods, from simple correlation studies to randomized controlled experiments. There have also been a variety of systematic reviews, many conducted for the Campbell Collaboration (see www.campbellcollaboration.org) in addition to the Maryland Report that have organized this research to glean generalizations on “what works.” In 2004, the National Research Council also conducted a larger review of the gamut of police research (see National Research Council 2004).

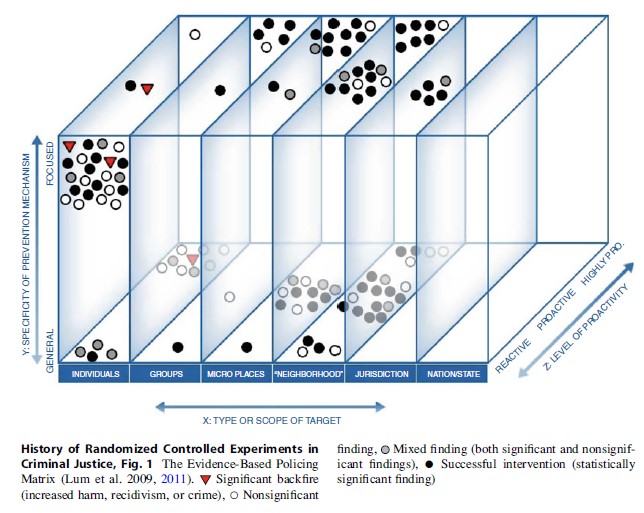

Currently, the most comprehensive and consistently updated systematic review of evaluations of the range of police crime control interventions is the Evidence-Based Policing Matrix (Lum et al. 2011; see also www. policingmatrix.org). The Matrix (shown in Fig. 1) is a web-based tool that houses all police crime control intervention research of moderate to high quality. For studies to be included in the Matrix, evaluations must at least include a comparison unit of analysis that did not receive an intervention – similar to a Maryland Report SMS score of “3” or higher. The Matrix classifies all police intervention researches on three very common dimensions of crime prevention strategies: the nature and type of target, the degree to which the strategy is reactive or proactive, and the strategy’s level of focus (i.e., the specificity of the prevention mechanism it used). The Matrix also color-codes studies by the outcome and significance of their findings. By “mapping” studies using these three dimensions, generalizations regarding the effectiveness of interventions with these characteristics can be visualized more easily. The visualization allows for multiple aspects of an evaluation to be seen simultaneously including the type of intervention studied, the finding of the intervention, and the methodological rigor of the study. The visualization also allows for practitioners to see groupings of research findings quickly, thereby allowing for generalizations from the totality of the research.

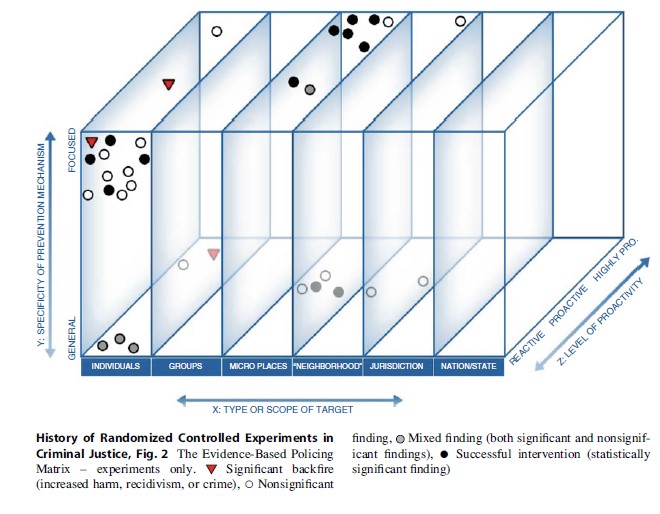

The explanation of the Matrix is covered in detail elsewhere (see Lum et al. 2011). However, it is used here to illustrate the relationship between experiments and evidence-based crime policy. Because the Matrix provides for generalizations from the large body of police evaluation research through its visualization, it is primarily intended as a research translation tool for practitioners (Lum 2009). This speaks to a core value of evidence-based crime policy – that research should be meaningful and useful to decision makers, not just other researchers. Given this, the Matrix creators decided to include in the visualization studies that were not randomized controlled trials (studies that at least had a comparison group present were also included). Had only experiments been included, the Matrix would appear as it does in Fig. 2.

While Fig. 2 can show a few important ideas for police deployment, and while it also can show where we need more high quality research, some usefulness is also lost from its original form in Fig. 1. As in Fig. 1, we can see that highly proactive, micro-place, focused approaches seem to work well in reducing crime, and that reactive strategies geared toward individuals, even when focused, are not promising (and may cause more harm). However, the sparsely populated Matrix in Fig. 2 may be less practical to police departments trying to move toward an evidence-based approach to developing deployment options because of the scarcity of information caused by the filtering of studies of weaker designs. At the same time, including non-RCTs in the Matrix may lead to false optimism about, for example, the impact of neighborhood-based approaches on crime, of which there are many in Fig. 1. While studies evaluating neighborhood approaches are promising, we know from Weisburd et al. (2001) that there is an inverse relationship between methodological ratings and positive study findings. The authors’ choice in including non-RCTs in this translation tool emphasizes their own compromise between pursuing evidence-based crime policy and upholding the importance of experiments in evaluating police interventions. Granted, this does not mean that evaluators should not strive toward using high quality research designs like experiments to evaluate interventions. But the comparison of Figs. 1 and 2 does show if we just focus on experiments, researchers may not have much to offer the policing community with regard to making deployment more evidence based (which could be discouraging for those advocating for evidence-based policing).

Both examples of the Maryland reviews and the Matrix indicate that the dearth of experimentation in criminal justice may not only result from difficulties in doing experiments. Experiments are part of the larger context of the evidence-based crime policy movement, whose proponents are still debating (and reconciling) the role of experiments in criminal justice policy.

The Infrastructure For Experimental Criminology

Amid this healthy debate about the role of experiments in evidence-based crime policy, there have also been efforts to create infrastructure to support experimental criminology that have become part of, and catalysts for, the history of the RCE. For example, the Campbell Collaboration (see http://www.campbellcollaboration. org) was formed – in part by efforts of those involved in the Maryland Report and by philanthropist Jerry Lee – to advocate for more rigorous evaluations of social interventions. Modeled after the Cochrane Collaboration for medical and public health interventions, the Campbell Collaboration sponsors systematic reviews and meta-analyses on specific areas (one major area being crime) to draw conclusions from the totality of evaluation research on a specific topic. The purpose of these reviews is to succinctly inform decisions makers about what the totality of the research says regarding a specific intervention. For example, if five studies examine the impact of pre-textual car stops to reduce gun violence and each has different findings, what can we conclude from all five studies? Like the Maryland Report, implied in this question is the need to rank studies on methodological rigor so that the most believable studies are relied upon more to draw such conclusions (Petrosino et al. 2003). The Campbell Collaboration, like the Maryland Report, again emphasizes the importance of ranking evaluations based on methods, thus emphasizing the importance of experimentation and its connectivity to evidencebased practice and policy. However, the Collaboration also is significant to the history of RCEs because it created organizational infrastructure and social networks around this idea, in not just criminal justice, but social interventions more generally.

Individuals involved in the Campbell Collaboration, especially Joan McCord, David Farrington, Lawrence Sherman, Jerry Lee, David Weisburd, Lorraine Green Mazerolle, Anthony Braga, Joan Petersilia, Frederick Losel, Doris MacKenzie, Denise Gottfredson, David Olds, Jonathan Shepherd, Anthony Petrosino, Robert Boruch, Mark Lipsey, David Wilson, and others, also helped to build the infrastructure to support experimentation by forming the Academy of Experimental Criminology (AEC) in 1999. The AEC was established to recognize and encourage the efforts of scholars who had conducted experiments in the field through its Academy Fellows distinction. At the time of writing, there were 60 AEC fellows and 13 honorary fellows, all prominent members of the criminology community. In 2009, members of the AEC petitioned the American Society of Criminology membership to form the Division of Experimental Criminology (DEC). The DEC is now one of eight divisions within the American Society of Criminology and, in 2012, combined its efforts with the AEC through a joint web site and mutual activities (for more information on the DEC, see www.cebcp.org/dec). The further prominence and importance of experiments was reflected in the rising prestige of The Journal of Experimental Criminology (JEC). Since its inception (2005) through the end of 2012, 86 of the 164 main articles have been experiments, while another 27 of the articles are meta-analyses or systematic reviews of research.

In addition to these organizations, a number of university centers related to evidence-based crime policy and experimental criminology, as well as more graduate training and presentations at conferences, helped build the infrastructure to support experimentation. Both authors’ home centers, the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy (see www.cebcp.org) and the Australian Research Council funded Center for Excellence in Policing and Security (see www.ceps.edu.au), are examples of these efforts. Jerry Lee, the philanthropist mentioned above, also established Centers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Cambridge to carry out more experimental evaluations. Mr. Lee also helps fund the Stockholm Prize in Criminology, in which a number of experimentalists, including David Weisburd, Jonathon Shepherd, David Olds, and Friedrich Lo¨ sel, have been recipients.

The infrastructure supporting experimentation has also been facilitated by the federal funding arena, through in requirements in solicitations for funding by the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs and the National Institute of Justice (NIJ). Numerous NIJ directors have supported more experimentation for evaluating crime prevention interventions following the efforts by James “Chips” Stewart who served from 1982 to 1990 and led more recently by Assistant Attorney General Laurie Robinson.

In current funding solicitations by NIJ, for example, the following wording appears:

Within applications proposing evaluation research, funding priority will be given to experimental research designs that use random selection and assignment of participants to experimental and control conditions. When randomized designs are not feasible, priority will be given to quasi-experimental designs that include contemporary procedures such as Propensity Score Matching or Regression Discontinuity Design to address selection bias in evaluating outcomes and impacts.

Research and Evaluation in Justice Systems (NIJ solicitation number SL000981)

The Office of Justice Programs, under the leadership of Laurie Robinson, has also developed CrimeSolutions.gov, which, like the Mary land Report, judges studies of interventions by their methodological rigor and internal validity. Again, such rankings consistently highlight the importance of experimentation in evidence-based crime policy despite continuing debates.

The Future Of Experiments

The history (and future) of randomized controlled experiments in criminal justice and criminology does not occur in a vacuum and cannot simply rely on the scientific merits of experimentation. Not only must RCEs answer to methodological challenges about their ability to establish causation, but perhaps an equally large obstacle to the future of experimentation is whether it can survive criticisms of evidence-based crime policy (and vice versa).

On a more fundamental level, the interaction and history of experimentation and evidence-based crime policy reflects a broader debate and discussion about the role of science in modern democracies. The ideology that science is important in governance and public health seems more accepted in the realm of medicine than social interventions. We hope that medical treatments have been tested in rigorous ways so that we can be assured that treatments will help us. The debates over the merits of experimentation in criminal justice interventions continue because science does not enjoy such acceptance in this realm.

Bibliography:

- Baird J (2011) Descriptive validity and statistical power: a review of experiments published in criminology from 1980–2011. Unpublished manuscript. George Mason University, Fairfax

- Berk R (2005) Randomized experiments as the bronze standard. J Exp Criminol 1(4):417–433

- Boruch R, Snyder B, DeMoya D (2000a) The importance of randomized field trials. Crime Delinq 46(2): 156–180

- Boruch R, Victor T, Cecil JS (2000b) Resolving ethical and legal problems in randomized experiments. Crime Delinq 46(3):330–353

- Burtless G (1995) The case for randomized field trials in economic and policy research. J Econ Perspect 9(2):63–84

- Campbell D, Stanley J (1963) Experimental and quasiexperimental designs for research on teaching. In: Gage NL (ed) Handbook of research on teaching. Rand McNally: American Educational Research Association, Chicago, pp 171–247

- Clarke R, Cornish D (1972) The controlled trial in institutional research: paradigm or pitfall for penal evaluators? vol 15, Home office research studies. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London

- Cook T (2003) Resistance to experiments: why have educational evaluators chosen not to do randomized experiments? Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 589:114–149

- Farrington D (1983) Randomized experiments on crime and justice. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, vol IV. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 25–308

- Farrington D (2003a) Methodological quality standards for evaluation research. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 587:49–68

- Farrington D (2003b) A short history of randomized experiments in criminology: a meager feast. Eval Rev 27(3):218–227

- Farrington D, Welsh B (2006) A half-century of randomized experiments on crime and justice. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice, vol 34. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 55–132

- Heckman J, Smith J (1995) Assessing the case for social experiments. J Econ Perspect 9(2):85–110

- Hough M (2010) Gold standard or fool’s gold: the pursuit of certainty in experimental criminology. Criminol Crim Justice 10:11–32

- Kelling G, Pate A, Dieckman D, Brown C (1974) The Kansas city preventive patrol experiment: summary report. The Police Foundation, Washington, DC

- Lipton D, Martinson R, Wilks J (1975) The effectiveness of correctional treatment: a survey of treatment evaluation studies. Praeger, New York

- Lum C (2009) Translating police research into practice, Ideas in American policing lecture series. Police Foundation, Washington, DC

- Lum C, Yang S (2005) Why do evaluation researchers in crime and justice choose non‐experimental methods? J Exp Criminol 1(2):191–213

- Lum C, Koper C, Telep CW (2011) The evidence-based policing matrix. J Exp Criminol 7:3–26

- Lum C, Telep C, Koper C, Grieco J (2012) Receptivity to research in policing. Justice Res Pol 14(1):61–96

- MacKenzie D (2002) Reducing the criminal activities of known offenders and delinquents: crime prevention in the courts and corrections. In: Sherman LW, Farrington DP, Welsh BC, MacKenzie DL (eds) Evidence based crime prevention. Routledge, London, pp 330–404

- MacKenzie D (2008) Examining what works in corrections. In: Proceedings of the 16th annual ICCA research conference keynote address, St. Louis

- Martinson R (1974) What works? Questions and answers about prison reform. Pub Interest 35:22–54

- Maynard R (1980) The impact of supported work on young school dropouts. Manpower Demonstration Research Corp, New York

- Mazerolle L, Price J, Roehl J (2000) Civil remedies and drug control: a randomized field trial in Oakland, CA. Eval Rev 24(2):212–241

- McCord J (1978) A thirty-year follow-up of treatment effects. Am Psychol 33(3):284–289

- McCord J (2003) Cures that harm: unanticipated outcomes of crime prevention programs. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 587:16–30

- National Research Council (2004) Fairness and effectiveness in policing: the evidence. Committee to review research on police policy and practices. In: Skogan W, Frydl K (eds) Committee on Law and justice, division of behavioral and social sciences and education. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

- Olds D, Henderson C, Cole R, Eckenrode J, Kitzman H, Luckey D, Powers J (1998) Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children’s criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 280:1238–1244

- Palmer T, Petrosino A (2003) The “experimenting agency”: the California youth authority research division. Eval Rev 27:228–266

- Pawson R, Tilley N (1997) Realistic evaluation. Sage, London

- Petersilia J (1989) Implementing randomized experiments – lessons from BJA’s intensive supervision project. Eval Rev 13(5):435–458

- Petersilia J, Turner S (1993) Intensive probation and parole. Crime Justice Rev Res 17:281–335

- Petrosino A, Boruch R, Farrington D, Sherman L, Weisburd D (2003) Toward evidence-based criminology and criminal justice: systematic reviews, the Campbell collaboration, and the crime and justice group. Int J Comp Criminol 3:42–61

- Powers E, Witmer H (1951) An experiment in the prevention of delinquency. Columbia University Press, New York

- Pratt T, Gau J, Franklin T (2011) Key ideas in criminology and criminal justice. Sage, Los Angeles

- Shadish W, Cook T, Campbell D (2002) Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inferences. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston

- Shepherd J (2003) Explaining feast of famine in random-ized field trials. Eval Rev 27(3):290–315

- Sherman L, Berk R (1984) The Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment. Police Foundation, Washington, DC

- Sherman L (1998) Evidence-based policing, Second invitational lecture on ideas in policing. Police Foundation, Washington, DC

- Sherman L, Weisburd D (1995) General deterrent effects of police patrol in crime hot spots: a randomized controlled trial. Justice Quart 12:625–648

- Sherman L, Gottfredson D, MacKenzie D, Eck J, Reuter P, Bushway S (1997) Preventing crime: what works, what doesn’t, what’s promising: a report to the United States Congress. National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

- Sherman L, Farrington D, Welsh B, MacKenzie D (eds) (2002) Evidence based crime prevention. Routledge, London

- Sparrow M (2009) One week in Heron city. In: Harvard executive session on policing and public safety. National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC

- The Police Foundation (1981) The Newark foot patrol experiment. Police Foundation, Washington, DC

- Weisburd D (2000) Randomized experiments in criminal justice policy: prospects and problems. Crime Delinq 46(2):181–193

- Weisburd D (2003) Ethical practice and evaluation of interventions in crime and justice: the moral imperative for randomized trials. Eval Rev 27(3): 336–354

- Weisburd D, Green L (1995) Policing drug hot spots: the Jersey city drug market analysis experiment. Justice Quart 12:711–736

- Weisburd D, Petrosino A (2004) Experiments, criminology. In: Kempf-Leonard K (ed) Encyclopedia of social measurement. Academic, San Diego

- Weisburd D, Lum C, Petrosino A (2001) Does research design affect study outcomes? Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 578:50–70

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.