This sample Hot Spots and Place-Based Policing Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Over the past two decades, a series of rigorous evaluations have suggested that police can be effective in addressing crime and disorder when they focus in on small units of geography with high rates of crime (see Braga et al. in press; National Research Council [NRC] 2004; Weisburd and Eck 2004). These areas are typically referred to as hot spots, and policing strategies and tactics focused on these areas are usually referred to as hot spots policing or place-based policing. This place-based focus stands in contrast to traditional notions of policing and crime prevention more generally, which have often focused primarily on people (see Weisburd 2008). For example, police work often begins with a response to citizens who call the police, and police are very focused on identifying and arresting offenders who commit crimes. While hot spots policing does not ignore the offenders found within crime hot spots, the focus is very much on the places where crime is occurring.

Police, of course, have never ignored geography entirely. Police beats, precincts, and districts determine the allocation of police resources and dictate how police respond to calls and patrol the city. With place-based policing, however, the concern is with much smaller units of geography than the police have typically focused on. Places here refer to specific locations within the larger social environments of communities and neighborhoods, such as addresses or street blocks. Crime prevention effectiveness is maximized when police focus their resources on these micro-units of geography.

The evidence suggesting the effectiveness of place-based policing efforts is detailed in the sections that follow. A definition of crime hot spots is first discussed followed by a review of research suggesting that crime is highly concentrated at micro-units of geography, and these concentrations remain stable over time. Hot spots policing is then defined, and the strategies place-based policing can entail are discussed. The extent to which hot spots policing has diffused across American policing is also examined. The empirical evidence for hot spots policing and the different approaches to addressing high crime places are then reviewed. Finally, some suggestions for future research are presented.

Defining Crime Hot Spots And The Concentration Of Crime At Place

Defining Crime Hot Spots

Crime hot spots are small units of geography with high rates of criminal activity. The specific geographic area that makes up a hot spot varies across studies, ranging from individual addresses or buildings (e.g., Sherman et al. 1989), to single street segments (i.e., both sides of a street from intersection to intersection; e.g., Sherman and Weisburd 1995), to small groups of street segments with similar crime problems such as a drug market (e.g., Weisburd et al. 2006). Hot spots are smaller than the units that police departments typically use for dividing up patrol resources such as patrol beats, zones, or sectors. Hot spots can be viewed as micro-places, to differentiate them from larger geographic units such as communities and neighborhoods that have traditionally been of interest to criminologists discussing crime and place (see Weisburd 2008).

There is also no firm rule as to how much crime must be found in a micro-place before it can be categorized as a hot spot. This will vary across studies and contexts, based on the overall rate of crime in a jurisdiction. In the studies of hot spots policing described below, hot spots are typically defined by drawing upon a rank ordered list of the highest crime locations (e.g., addresses or streets) in the city based on calls for service or crime incidents. Thus, places are not defined as crime hot spots by reaching an absolute threshold of crime, but instead because of extremely high levels of criminal activity relative to other places in the city.

Crime Concentration At Hot Spots

Regardless of how hot spots are defined, a number of studies over the past 20 to 30 years have found that a relatively small number of micro-places are responsible for a significant amount of total crime in a city (e.g., see Weisburd and Mazerolle 2000; Weisburd et al. 2004). The hottest spots in a city, regardless of the specific unit of analysis chosen, are responsible for a large chunk of a jurisdiction’s crime problem. Perhaps the most influential of these studies was Sherman et al.’s (1989) analysis of emergency calls to street addresses over a single year. Sherman et al. found that only 3.3 % of the addresses in Minneapolis, Minnesota, produced just over 50 % of all calls to the police. If crime were randomly distributed across the 115,000 addresses in Minneapolis, one would not expect any places to have 15 or more calls in a single year. Instead, Sherman et al. found 3,841 such addresses, indicating that crime is far more concentrated than would be expected by chance.

A study conducted by Weisburd et al. (2012) not only confirms the concentration of crime, but also the stability of such concentrations across a long time span. Weisburd et al. examined street segments in the city of Seattle from 1989 through 2004. They found that each year, 50 % of crime incidents occurred on between 4.7 and 6.1 % of the street segments. These data overall illustrate a kind of “law of concentration” for crime, suggesting that crime is heavily clustered in cities with fewer than 5 or 10 % of addresses, street segments, or small clusters of addresses and street segments accounting for a majority of crime in a city each year (Weisburd et al. 2012). Thus, police can target a sizable proportion of citywide crime by focusing in on a small number of places.

Sherman (1995) argues that such clustering of crime at places is even greater than the concentration of crime among individuals. Comparing the concentration of calls in Minneapolis to the concentration of offending in the Philadelphia birth cohort study, he notes that future crime is “six times more predictable by the address of the occurrence than by the identity of the offender” (1995: 36-37). Sherman asks, “Why aren’t we thinking more about wheredunit, rather than just whodunit?”

The Stability Of Crime Hot Spots

Concentration by itself has important implications for the effectiveness of hot spots policing. However, it is also important to examine the stability of crime hot spots over time. If hot spots of crime shift rapidly from place to place each year, it makes little sense to focus crime control resources at such locations, because they would naturally become free of crime without any criminal justice intervention (Spelman 1995).

Data on crime stability suggests that hot places tend to remain hot over time. Spelman (1995), for example, examined calls for service at schools, public housing projects, subway stations, and parks and playgrounds in Boston. He found evidence of a very high degree of stability of crime at the “worst” of these places over a 3-year period. Spelman concluded that it “makes sense for the people who live and work in high-risk locations, and the police officers and other government officials who serve them, to spend the time they need to identify, analyze and solve their recurring problems” (1995: 131).

The most comprehensive examination of the stability of crime at place over time was conducted by Weisburd et al. (2012) in their study of crime incidents at street segments in Seattle. Using group-based trajectory analysis to categorize street segments according to similar developmental patterns, they identified 22 specific trajectory groups. The most important finding in their study was that crime remained fairly stable at places over time, particularly in a small group of high crime segments they refer to as the “chronic group.” These street segments remained among the hottest in the city throughout the 16year study period. Representing just 1 % of the street segments in Seattle, the chronic streets accounted for 22 % of the crime in the city. Hot spots of crime thus appear to remain hot over long periods of time. This can be contrasted with developmental studies of individual offending where there is often tremendous change across relatively short periods, especially for high-rate offenders (see Horney et al. 1995), and a great deal of variability across the life-course as many high-rate “hot” offenders in adolescence age out of crime and cool off in adulthood.

The Distribution Of Crime Hot Spots

How are hot spots of crime distributed geographically across cities? This question is important to explore, because it gets at the issue of whether it is necessary for police to focus in on micro-places for hot spots policing. For example, if all the crime hot spots were concentrated in only one or two neighborhoods in a city, then neighborhood or beat-level initiatives might be just as effective as hot spots approaches in addressing crime concentrations.

Evidence to date suggests that crime hot spots can be found throughout a city. Weisburd and Mazerolle (2000), for example, identified 56 drug markets in Jersey City, New Jersey. Although the drug markets were more concentrated in socially disadvantaged areas, they could even be found in areas that were generally seen as more established and better off. Weisburd and Mazerolle argued that even “good” neighborhoods can have “bad” places. Importantly, most places even in very disadvantaged neighborhoods were relatively free of serious drug problems.

Groff et al. (2010) examined the distribution of all crime hot spots in Seattle. While hot spots may be more likely in high activity places in the city like the central business district, they tend to be found in a variety of different neighborhoods, and even neighborhoods with higher concentration of hot spots tend to have a sizable proportion of crime free locations. Groff et al. (2010) conclude that much information about crime would be missed by focusing on larger units such as neighborhoods. These findings overall suggest the usefulness of a policing approach that narrows the focus to hot street segments or micro-places as opposed to hot neighborhoods or hot communities.

Place Risk Factors

Research by Weisburd and colleagues (2012) provides new insights into the key risk factors that help explain whether places become hot spots or not. They overall find that social and opportunity factors are very highly concentrated at the street block level, and these concentrations are generally very closely linked to concentrations of crime. This suggests that certain factors may contribute to street segments remaining hot spots of crime over time, and hence could be viewed as criminogenic risk factors for a street becoming (and remaining) a crime hot spot.

Some of these factors present opportunities for the police in addressing crime at chronic hot spot streets. For example, the number of employees working on a block is a strong predictor of a street segment being a chronic hot spot. While the police have little control over the number of people working on a block, they can control the level of guardianship they provide on each block and how they approach the potential crime attractors and generators on each block (e.g., working to install CCTV in parking areas on streets with many employees to address car break-ins). As another example, higher numbers of high-risk juveniles (defined as those with high rates of truancy or poor school performance) on a block substantially increased the likelihood a street would be a chronic hot spot. Increased enforcement from police could reduce levels of truancy and limit the amount of time these juveniles spend on their street unsupervised.

Current State Of Hot Spots Policing

What Is Hot Spots Policing?

Hot spots policing, also sometimes referred to as place-based policing (see Weisburd 2008), covers a range of police responses that all share in common, a focus of resources on the locations where crime is highly concentrated. Just as the definition of hot spots varies across studies and contexts, so do the specific tactics police use to address high crime places. There is no one way to implement hot spots policing. As Weisburd (2008) notes, approaches can range rather dramatically across interventions.

For example, the strategies of place-based policing can be as simple as dramatically increasing officer time spent at hot spots patrol, as was the case in the Minneapolis Hot Spots Policing Experiment (Sherman and Weisburd 1995). But placebased policing can also take a much more complex approach to the amelioration of crime problems. In the Jersey City Drug Market Analysis Project (Weisburd and Green 1995), for example, a three-step program (including identifying and analyzing problems, developing tailored responses, and maintaining crime control gains) was used to reduce problems at drug hot spots. In the Jersey City Problem-Oriented Policing Project (Braga et al. 1999), a problem-oriented policing approach was taken in developing a specific strategy for each of the small areas defined as violent crime hot spots. The results of these interventions are discussed more in the next section.

Are Agencies Using Hot Spots Policing?

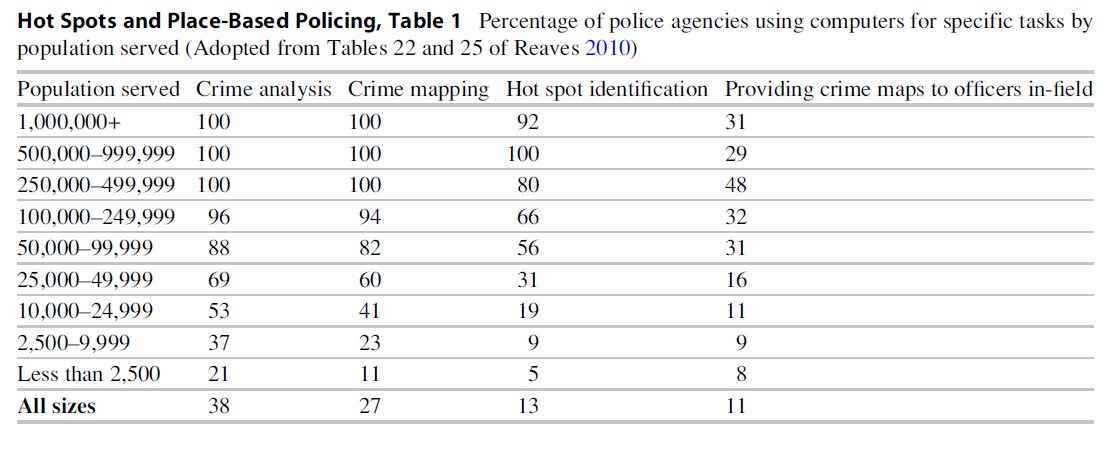

To what extent are police agencies using hot spots policing in practice? To answer this, data from the 2007 Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS) data were examined (see Reaves 2010), as well as survey data that asked police agencies about hot spots policing. While data on specific tactics are limited in the LEMAS survey, there are a number of questions related to police technology (see Table 1). Crime analysis and crime mapping, in particular, are very important for the successful implementation of hot spots policing. The results overall suggest widespread use of these technologies in larger departments but not in smaller ones. For example, while over 90 % of the largest agencies are using computers for hot spot identification, just 13 % of departments overall are. Even in moderately sized cities (population 100,000–249,999), just 56 % of departments use computers to identify hot spots. When it comes to using computers for crime analysis and crime mapping, results are similar. One hundred percent of the largest departments make use of computers for such tasks, but only 38 % of agencies overall use computers for crime analysis, and 27 % use computers for crime mapping. In terms of patrol officer’s access to crime data, just 31 % of the largest agencies and 11 % of agencies overall provide officers access to crime maps in their patrol cars.

The use of computers for crime mapping and analysis has increased since the 2003 LEMAS survey. For example, the percentage of officers working in a department that uses computers for crime mapping jumped from 57 % in 2003 to 75 % in 2007 and for hot spot identification the increase was from 45 % in 2003 to 58 % in 2007 (Reaves 2010). Research by Weisburd and Lum (2005) suggests that the use of crime mapping diffused quickly across policing from the mid-1990s through 2001. They note that the adoption of crime mapping was closely linked to the use of hot spots policing. When agencies were asked why they developed crime mapping in the department, the largest response category was “to facilitate hot spots policing.” Kochel (2011: 352) cites similar statistics, noting “Within 15 years, hot spots policing had diffused almost completely throughout large U.S. police departments.” These latest LEMAS data suggest that the use of crime mapping continues to increase, but smaller agencies are lagging behind.

Data on the adoption of hot spots policing also come from a Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) survey of 176 policing agencies of various sizes on their efforts to reduce violent crime (Koper 2008). Responses showed close to twothirds (63 %) of agencies used hot spots policing to reduce violent crime. This was by far the most popular response to the question of how to address violence. When asked what sort of places the agency defines as a hot spot, the majority of respondents noted addresses or intersections (61 %) or clusters of addresses (58 %). However, a majority of respondents (57 %) also identified neighborhoods as potential hot spots and a sizable minority pointed to patrol beats (41 %) as the sort of place that would be defined as a hot spot. Crime is not as highly concentrated at these larger units of geography, so focusing on them may not produce the same crime control benefits as using more micro-units of analysis.

The PERF survey also provides data on what tactics agencies are using to respond to homicide, robbery, assault, gang violence, and drug crime hot spots. While agencies identified a number of different potential responses to hot spots, the top responses in each category tended to be some combination of problem solving and analysis, directed patrol, community policing/partnerships, and targeting known offenders (Koper 2008). These strategies and the empirical evidence supporting them are discussed more below, focusing, in particular, on problem solving and directed patrol.

It is important to note that while the data discussed above provide an estimate of the extent to which police agencies have adopted hot spots policing, they do not make clear how frequently agencies are actually using hot spots policing in practice. In other words, while it appears that a substantial portion of larger agencies are using computers to identify crime hot spots, what percentage of officer time is actually being spent on hot spots policing in these agencies? Data on the level of implementation of hot spots policing is not available at the department level, but such data would be important to better understand to what extent hot spots policing is becoming a primary tactic in police agencies.

Empirical Evidence On The Effectiveness Of Hot Spots Strategies

The evidence base for the effectiveness of hot spots policing in reducing crime and disorder is particularly strong. As the NRC (2004: 250) review of police effectiveness noted, “studies that focused police resources on crime hot spots provided the strongest collective evidence of police effectiveness that is now available.” The Braga et al. (in press) systematic review came to a similar conclusion; although not every hot spots study has shown statistically significant findings, the vast majority of such studies have (20 of 25 tests from 19 experimental or quasi-experimental evaluations reported noteworthy crime or disorder reductions), suggesting that when police focus in on crime hot spots, they can have a significant beneficial impact on crime in these areas. In Braga and colleagues’ (in press) metaanalysis, they found an overall mean effect size of 0.184, suggesting a significant benefit of the hot spots approach in treatment compared to control areas. As Braga (2007: 18) concluded “extant evaluation research seems to provide fairly robust evidence that hot spots policing is an effective crime prevention strategy.”

Importantly, there was little or no evidence to suggest that spatial displacement was a major concern in hot spots interventions. Spatial crime displacement is the notion that efforts to eliminate specific crimes at a place will simply cause criminal activity to move elsewhere, thus negating any crime control gains. Braga et al. (in press) found significant evidence of spatial displacement in only one study (Ratcliffe et al. 2011) and even here the amount of displacement was far less than the main crime prevention benefit of the intervention. Thus, in nearly every study, crime did not simply shift from hot spots to nearby areas (see also Weisburd et al. 2006). Indeed, a more likely outcome of such interventions was a diffusion of crime control benefits (Clarke and Weisburd 1994) in which areas surrounding the target hot spots also showed a crime and disorder decrease. Displacement is not inevitable, in part, because hot spots tend to have specific features that make them attractive targets for criminal activity, and these same features may not exist on neighboring blocks. For example, in the Weisburd et al. (2006) study, the prostitution hot spot targeted by police had few homes and many vacant buildings, making it an attractive site for prostitution activity. In contrast, one of the catchment areas near the target site had many more residences, making it more likely that the police would be called when prostitution occurred. In this context, prostitutes could not easily move their illegal activity to areas nearby.

The experimental evidence on hot spots policing is discussed below, focusing when possible on what tactics seem to be most effective in addressing crime hot spots. The literature has not provided the same level of guidance on what specifically police officers should be doing at hot spots to most effectively reduce crime. As Braga (2007: 19) notes “Unfortunately, the results of this review provide criminal justice policy makers and practitioners with little insight on what types of policing strategies are most preferable in controlling crime hot spots.” The update to Braga’s (2007) review by Braga and colleagues (in press) does provide some additional guidance, suggesting that problem-oriented hot spots interventions may be somewhat more effective than simply increasing police presence, although the authors caution these comparisons are based on a small number of studies.

The first randomized experiment on hot spots policing, the Minneapolis Hot Spots Patrol Experiment (Sherman and Weisburd 1995), used computerized mapping of crime calls to identify 110 hot spots of roughly street-block length. Police patrol was doubled on average for the experimental sites over a 10-month period. Officers in Minneapolis were not given specific instructions on what activities to engage in while present in hot spots. They simply were told to increase patrol time in the treatment hot spots, and the activities they engaged in ranged a good deal from more proactive problem-solving efforts to simply sitting in the car parked in the center of a hot spot street segment. The study found that the experimental as compared with the control hot spots experienced statistically significant reductions in crime calls and observed disorder. The significant decline in calls for service was driven largely by a decline in soft crime calls (e.g., disturbances, drunks, noise, and vandalism). While soft crime calls declined 7.2–15.9 % in the treatment group relative to the control group, depending on the time period examined, hard crime calls, (e.g. burglaries, auto thefts, and assaults) declined a non-statistically significant 2.6–5.9 %.

The results overall though suggested increased police presence could have a significant effect on crime, particularly disorder and less serious crime. This marked a major change from the conventional wisdom about the impact the police could have on crime. The most influential prior study of police patrol at the time was the Kansas City Preventive Patrol Experiment (Kelling et al. 1974), which found that neither doubling nor removing preventive patrol in a beat had a significant impact on crime or victimization. The finding that police randomly patrolling beats is not an effective crime deterrent makes sense based on the review of the crime concentration literature above. Since crime is very concentrated across cities, it makes little sense from an effectiveness and efficiency standpoint to respond with a strategy relying on the random distribution of police resources across large geographic areas. The Minneapolis study and the other hot spots studies described below suggested police could have an impact on crime by appropriately focusing their resources on the locations where crime was highly concentrated.

Significant crime and disorder declines are also reported in five other randomized controlled experiments that tested a more tailored, problem-oriented approach (see Braga and Weisburd 2010) to dealing with crime hot spots. In the Jersey City Problem-Oriented Policing in Violent Places experiment (Braga et al. 1999), the exact response varied by hot spot, but the responses all included some aspect of aggressive order maintenance and most included efforts to make physical improvements to the area (e.g., removing trash, improving lighting) and drug enforcement. Strong statistically significant reductions in total crime incidents and total crime calls were found in the treatment hot spots relative to the control hot spots. Social and physical observation data showed improvement in visible disorder in 10 of the 11 treatment areas compared to the control sites after the intervention.

In the Jersey City Drug Market Analysis Program experiment (Weisburd and Green 1995), a step-wise problem-solving model was compared to generalized enforcement in drug hot spots. The treatment group received a three-stage intervention. In the planning stage, officers collected data on the physical, social, and criminal characteristics of each area; in the implementation stage, officers coordinated efforts to conduct a crackdown at the hot spot and used other relevant responses to address underlying problems; and finally, in the maintenance stage, officers attempted to maintain the positive impact of the crackdown. The experimental sites had significantly smaller increases in disorder calls compared to the control sites. In particular, the project had a positive impact on calls related to public morals and suspicious persons.

In the Oakland Beat Health study, Mazerolle and colleagues (2000) evaluated a civil remedies initiative to deal with high crime addresses and blocks. The intervention involved a police officer and police service technician visiting a site to identify and analyze the problem and to make contact with the property owner or place manager to try to address the problems. The intervention typically involved pressuring third parties (e.g., the landlord of a problem apartment building) to make changes to improve property conditions or face the possibility of civil action. Results showed significant reductions in drug calls for service at the treatment hot spots relative to the controls.

In Lowell, Massachusetts, a problem-oriented policing intervention to address disorder was associated with a statistically significant 20 % reduction in crime and disorder calls for service at the treatment hot spots compared to the control hot spots (Braga and Bond 2008). Systematic observations confirmed the official crime data results, showing significant reductions in social and physical disorder at the treatment places relative to the control places.

The Braga and Bond (2008) experiment also included a mediation analysis to assess which hot spots strategies were most effective in reducing crime. Results suggested that situational prevention strategies had the strongest impact on crime and disorder. Situational strategies are concerned with the physical, organizational, and social environments that make crime possible, and they focus on efforts to disrupt situational dynamics that allow crime to occur by, for example, increasing risks or effort for potential offenders or reducing the attractiveness of potential targets. Such approaches are often a prominent part of hot spots interventions, particularly those involving problem solving and include things like securing lots, razing abandoned buildings, and cleaning up graffiti. Increases in misdemeanor arrests made some contribution to the crime control gains in the treatment hot spots, but were not as influential as the situational efforts. Social service interventions did not have a significant impact on crime and disorder. These findings suggest not only the importance of situational crime prevention as a strategy for addressing crime facilitators in hot spots, but also that aggressive order maintenance through increases in misdemeanor arrests may not be the most effective way of addressing high disorder places. The potential negative consequences of intensive enforcement in the form of decreased perceptions of police legitimacy are discussed below (see Braga and Weisburd 2010).

More recently, in an important experimental study in Jacksonville, Florida, Taylor et al. (2011) were the first to compare different hot spot treatments in the same study with one treatment group receiving a more standard saturation patrol response and the second receiving a problem-oriented response that focused on officers analyzing problems in the hot spot and responding with a more tailored solution. Results showed a decrease in crime (though not a statistically significant decrease) in the saturation patrol hot spots, but this decrease lasted only during the intervention period and disappeared quickly thereafter. In the problem-oriented policing hot spots, there was no significant crime decline during the intervention period, but in the 90 days after the experiment, street violence declined by 33 % (a statistically significant decline). These results offer the first experimental evidence suggesting that problem-oriented approaches to dealing with crime hot spots may be more effective than simply increasing patrols in high crime areas. They also suggest that problem-solving approaches may take more time to show beneficial results, but any successes that come from a problem-oriented framework may be more long-lasting in nature.

Braga and Weisburd (2010) detail the desirability of problem-oriented policing as a strategy for long-term crime reduction in chronic hot spots. They recognize that even when agencies use problem-solving approaches, they often tend to prioritize more traditional, enforcement-oriented responses. Drawing upon the results of Braga and Bond (2008) and other hot spots studies, they argue that “situational” problem-oriented policing is not only more innovative but also more likely to produce significant crime control benefits. As they conclude “based on the available empirical evidence, we believe that police departments should strive to develop situational prevention strategies to deal with crime hot spots. Careful analyses of crime problems at crime hot spots seem likely to yield prevention strategies that will be well positioned to change the situations and dynamics that cause crime to cluster at specific locations” (Braga and Weisburd 2010: 182–183).

Two other recent experiments shed new light on the effectiveness of particular approaches to dealing with crime hot spots. While the initial Minneapolis study did not include a systematic examination of officer activities in the hot spots, subsequent analyses by Koper (1995) provide some insight into how much time officers should be spending in hot spots to maximize residual deterrence. Koper analyzed observational data on nearly 17,000 instances when police drove through or stopped at a hot spot and examined the time from when the officer(s) left the location until the next occurrence of criminal or disorderly behavior. Using survival analysis techniques, he found that each additional minute of time officers spent in a hot spot increased survival time by 23 %. Survival time here refers to the amount of time after officers departed a hot spot before disorderly activity occurred. The ideal deal time spent in the hot spot was 14 to 15 min; after about 15 min, there were diminishing returns and increased time did not lead to greater improvements in residual deterrence. This phenomenon is often referred to as the “Koper curve” as graphing the duration response curve shows the benefits of increased officer time spent in the hot spot until a plateau point is reached at around 15 min (see Koper 1995, Fig. 1). As Koper (1995: 668) notes “police can maximize crime and disorder reduction at hot spots by making proactive, medium-length stops at these locations on a random, intermittent basis.” Koper (1995) argues for an approach in which police travel between hot spots, spending about 15 min in each hot spot to maximize residual deterrence, and moving from hot spot to hot spot in an unpredictable order, so that potential offenders recognize a greater cost of offending in these areas because police enforcement could increase at any moment.

These recommendations suggest a potential reason why an experimental hot spots intervention at crack houses in Kansas City had quickly decaying effects (Sherman and Rogan 1995). The crackdowns on drug locations led to significant but modest improvements in the experimental street blocks, but these crackdowns were only one-time events and hence, residual deterrence was limited. Within a few weeks, crime on the streets where crack houses were located returned to pre-crackdown levels.

Koper’s (1995) recommendations were recently applied to the design of a hot spots policing experiment in Sacramento, California. Officers were explicitly instructed to rotate between treatment group hot spots and to spend about 15 min in each hot spot. Results suggest the Koper (1995) approach to hot spots policing had a significant impact on crime. Treatment group hot spots had significantly fewer calls for service and Part I crime incidents than control group hot spots when comparing the 3-month period of the experiment in 2011 to the same period in 2010 (Telep et al. in press).

Ratcliffe and colleagues (2011) evaluated the impact of foot patrol in crime hot spots in a randomized experiment in Philadelphia. Foot patrol has traditionally been viewed as an effective strategy for reducing fear of crime, not actual crime. Results suggested significant declines in violence in the treatment hot spots compared to the control sites. The intervention was particularly effective for hot spots that reached a threshold of violence (i.e., the hottest hot spots). Overall, the 12-week intervention prevented a net total of 53 violent crimes in the target areas. These findings suggest the importance of reconsidering the effectiveness of foot patrol when intensive foot patrol is used in high crime micro-places.

Hot Spots Policing And Police Legitimacy

In sum, the empirical research is highly supportive of the effectiveness of hot spots policing in reducing crime and disorder. The effectiveness of policing, however, is also dependent on public perceptions of the legitimacy of police actions (NRC 2004; Tyler 1990). The police need the support and cooperation of the public to effectively combat crime and maintain social order in public spaces. Legitimacy here refers to the public belief that there is a responsibility and obligation to voluntarily accept and defer to the decisions made by authorities (Tyler 1990). A number of scholars have recently argued that intensive police interventions such as hot spots policing may erode citizen perceptions of the police (e.g., see Kochel 2011; Rosenbaum 2006). Rosenbaum (2006), for example, argues that enforcement-oriented hot spots policing runs the risk of weakening police-community relations. Aggressive tactics can drive a wedge between the police and communities, as the latter can begin to feel like targets rather than partners. This is particularly relevant in high crime minority communities where perceptions of the police already tend to be negative. This has implications for the crime control effectiveness of hot spots policing as Tyler (1990) has argued that legitimacy is an important predictor of long-term compliance with the law. If hot spots policing interventions weaken perceptions of legitimacy, then the short-term crime control gains from the intervention might be offset by long-term increases in criminal offending.

Despite arguments that intensive interventions such as hot spots policing will have negative impacts on police legitimacy, the limited evidence available from such interventions tends to suggest that citizens living in targeted areas welcome the increased police presence. Recent research from three cities in San Bernardino County, California, for example, found that a broken windows style intervention in street segments had no impact on resident perceptions of police legitimacy (Weisburd et al. 2011). It would also be useful to assess the views of residents of areas nearby hot spots and target sites to assess whether such interventions have spillover effects (either positive or negative) on legitimacy perceptions. Additionally, research to date has not attempted to measure how the individuals who were stopped and searched by the police perceive such programs. Ideally, a study would compare the perceptions of individuals stopped as part of a hot spots intervention to those stopped under standard routine preventive patrol. Braga and Weisburd (2010) describe a community-oriented approach to hot spots policing focused on community consultation on the tactics used in hot spots and efforts to ensure that hot spots policing strategies do not reduce levels of police legitimacy. The knowledge base on this important topic of how police fairness and effectiveness intersect in hot spots policing remains limited.

Conclusions And Future Research

Overall this research paper suggests that significant crime control benefits can result from the use of hot spots policing and place-based policing. Basic research suggests that the action of crime is at very small geographic units of analysis, such as street segments or small groups of street blocks. Such places also offer a stable target for police interventions, as contrasted with the constantly moving targets of criminal offenders. Crime at place is not simply a proxy for larger area or community effects; indeed, the basic research evidence suggests that much of the action of crime occurs at very small geographic units of place. This basic research is reinforced by a strong body of experimental evidence for the effectiveness of place-based policing in reducing crime and disorder without simply displacing crime to areas nearby. Additionally, rigorous evaluation research in policing suggests that place-based interventions, including hot spots policing, tend to be more effective than interventions focused on people (Weisburd and Eck 2004).

While hot spots policing already has a larger evidence base than many police interventions, there are still areas where future research can shed new light. First, as noted above, additional research is needed on how hot spots policing impacts perceptions of police legitimacy in hot spot locations and the implications this has for the long-term effects of intensive police efforts. In particular, studies to date have not adequately examined the perceptions of offenders arrested or stopped in hot spot areas. Second, nearly all hot spots studies have taken place in highly populated urban areas. While smaller departments with only a few officers are unlikely to have a significant quantity of street-block size hot spots, future research should better examine the applicability of hot spots policing across varying contexts. Third, there are no studies that examine the long-term effects of hot spots interventions. In some respects, this makes sense. Hot spots interventions that focus on increasing patrol time to maximize deterrence are not expected to have an impact long after the police have left. But more problem- oriented hot spots approaches are designed to have longer-term impacts by changing the dynamics of places and so longer follow-up periods would be desirable in future projects. Fourth and in a related way, there should be more research that examines how police can disrupt long-term crime concentrations. In other words, can police address certain criminogenic factors that would stop the same places from appearing in the chronic trajectory group year after year as they did in Seattle? Fifth, further study on the importance of time in understanding crime hot spots is needed. To date, researchers have typically focused on annual data to generate hot spot locations, but the year may not be the most appropriate temporal unit. Police agencies must find a balance between targeting areas that have shown some stability in crime rates over time, while also allowing for flexibility in shifting resources when data suggest the movement of hot spots or the emergence of new hot spots. Sixth, future research should consider the cost-effectiveness of hot spots policing. How much is crime reduced per dollar spent or unit of officer time devoted to hot spots policing? How does the cost-effectiveness of hot spots policing compare to other policing strategies such as random preventive patrol? Assessing cost-effectiveness is particularly important in times like the present when many police agencies are facing budget cuts.

Finally, there is a need for better data on what agencies are doing in the field. LEMAS, for example, suggests the largest agencies have many of the capabilities and technologies needed for properly implementing hot spots policing, but many smaller agencies still lag behind. LEMAS is limited though in providing data on what departments are engaged in day-today. Because it is a massive national survey, there are limits to the number of questions that can be asked about daily practices, and even with additional questions, the LEMAS data reflect the survey responses of only certain individuals in the department, who may not always have sufficient knowledge about daily practices to provide reliable data. Qualitative studies could potentially provide greater insight into what policing looks like at the street level. Qualitative or mixed methods approaches could help better assess to what extent departments are actually engaging in hot spots policing.

Bibliography:

- Braga AA (2007) The effects of hot spots policing on crime. Campbell collaboration systematic review final report. http://campbellcollaboration.org/lib/ download/118/. Accessed 15 Apr 2012

- Braga AA, Bond BJ (2008) Policing crime and disorder hot spots: a randomized controlled trial. Criminology 46:577–608

- Braga AA, Weisburd D (2010) Policing problem places: crime hot spots and effective prevention. Oxford University Press, New York

- Braga AA, Weisburd DL, Waring EJ, Mazerolle LG, Spelman W, Gajewski F (1999) Problem-oriented policing in violent crime places: a randomized controlled experiment. Criminology 37:541–580

- Braga AA, Papachristos AV, Hureau DM (in press) The effects of hot spots policing on crime: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Justice Quart

- Clarke RV, Weisburd D (1994) Diffusion of crime control benefits: observations on the reverse of displacement. In: Clarke RV (ed) Crime prevention studies, vol 2. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 165–184

- Groff ER, Weisburd D, Yang S-M (2010) Is it important to examine crime trends at a local “micro” level?: A longitudinal analysis of street to street variability in crime trajectories. J Quant Criminol 26:7–32

- Horney J, Osgood DW, Marshall IH (1995) Criminal careers in the short-term: intra-individual variability in crime and its relation to local life circumstances. Am Sociol Rev 60:655–673

- Kelling GL, Pate AM, Dieckman D, Brown C (1974) The Kansas city preventive patrol experiment: technical report. Police Foundation, Washington, DC

- Kochel TR (2011) Constructing hot spots policing: unexamined consequences for disadvantaged populations and for police legitimacy. Crim Just Pol Rev 22:350–374

- Koper CS (1995) Just enough police presence: reducing crime and disorderly behavior by optimizing patrol time in crime hot spots. Just Quart 12:649–672

- Koper CS (2008) The varieties and effectiveness of ‘hot spots’ policing: results from a national survey. Presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology, St. Louis

- Mazerolle LG, Price JF, Roehl J (2000) Civil remedies and drug control: a randomized trial in Oakland, California. Eval Rev 24:212–241

- National Research Council (2004) Fairness and effectiveness in policing: the evidence. Committee to review research on police policy and practices. In: Skogan W, Frydl K (eds) Committee on law and justice, division of behavioral and social sciences and education. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

- Ratcliffe J, Taniguchi T, Groff ER, Wood JD (2011) The Philadelphia foot patrol experiment: a randomized controlled trial of police patrol effectiveness in violent crime hotspots. Criminology 49:795–831

- Reaves BA (2010) Local police departments, 2007. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC

- Rosenbaum DP (2006) The limits of hot spots policing. In: Weisburd D, Braga AA (eds) Police innovation: contrasting perspectives. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 245–263

- Sherman LW (1995) Hot spots of crime and criminal careers of places. In: Eck JE, Weisburd D (eds) Crime and place, crime prevention studies, vol 4. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 35–52

- Sherman LW, Rogan DP (1995) Deterrent effects of police raids on crack houses: a randomized controlled experiment. Just Quart 12:755–782

- Sherman LW, Weisburd D (1995) General deterrent effects of police patrol in crime “hot spots”: a randomized, controlled trial. Just Quart 12:625–648

- Sherman LW, Gartin PR, Buerger ME (1989) Hot spots of predatory crime: routine activities and the criminology of place. Criminology 27:27–56

- Spelman W (1995) Criminal careers of public places. In: Eck JE, Weisburd D (eds) Crime and place, crime prevention studies, vol 4. Willow Tree Press, Monsey Taylor B, Koper CS, Woods DJ (2011) A randomized controlled trial of different policing strategies at hot spots of violent crime. J Exp Criminol 7:149–181

- Telep CW, Mitchell R,Weisburd D (in press). How much time should the police spend at crime hot spots? Answers from a police agency directed randomized field trial in Sacramento, California, Justice Quart

- Tyler TR (1990) Why people obey the law: procedural justice, legitimacy, and compliance. Yale University Press, New Haven

- Weisburd D (2008) Place-based policing, Ideas in American policing. Police Foundation, Washington, DC

- Weisburd D, Eck JE (2004) What can the police do to reduce crime, disorder, and fear? Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 593:42–65

- Weisburd D, Green L (1995) Policing drug hot spots: the Jersey City drug market analysis experiment. Just Quart 12:711–736

- Weisburd D, Lum C (2005) The diffusion of computerized crime mapping policing: linking research and practice. Police Prac Res Int J 6:419–434

- Weisburd D, Mazerolle LG (2000) Crime and disorder in drug hot spots: implications for theory and practice in policing. Police Quart 3:331–349

- Weisburd D, Bushway S, Lum C, Yang S-M (2004) Trajectories of crime at places: a longitudinal study of street segments in the city of Seattle. Criminology 42:283–321

- Weisburd D, Wyckoff LA, Ready J, Eck JE, Hinkle JC, Gajewski F (2006) Does crime just move around the corner? A controlled study of spatial displacement and diffusion of crime control benefits. Criminology 44:549–592

- Weisburd D, Hinkle JC, Famega C, Ready J (2011) The possible “backfire” effects of hot spots policing: an experimental assessment of impacts on legitimacy, fear and collective efficacy. J Exp Criminol 7:297–320

- Weisburd D, Groff ER, Yang S-M (2012) The criminology of place: street segments and our understanding of the crime problem. Oxford University Press, New York

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.