This sample International Crime Victimization Survey Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Surveys of people’s experience of crime are now well established. They go under various titles – “crime,” “victims,” or “victimization” surveys. This research paper places the International Crime Victimization Survey (ICVS) in the context of the development of other victimization surveys. It discusses the ICVS from the point of view of its main rationale for making international comparisons. It also looks at what has been done on the survey front in terms of international comparisons outside the context of the ICVS and what might be in store for the future.

Victimization surveys have focused on various types of potential victims, although most take a nationally representative sample of people living in private households, as is the case with the ICVS. Those sampled are asked whether they have recently been a victim of crime, regardless of whether the victimization was reported to the police. By including non-reported crimes, victimization surveys provide a different (and larger) count of crime to that from police records – which encompass in large part only crimes reported by victims and which the police choose to record. Several studies have shown that survey-based estimates of commonly committed crimes can give more reliable evidence as to their volume and trends than police figures (see, e.g., Lynch 2006). Victimization surveys also collect social and demographic information to show which groups most often fall victim to crime. Police information offers relatively little on this front.

The Development And Types Of Victimization Surveys

The first round of the ICVS took place in 1989 after about a decade and a half of victimization survey development. The most important early national victimization survey took place in the United States in the 1960s. This was followed in 1972 by the first round of what is now called the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), which has been conducted continuously since. Early victimization surveys were also carried out in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Finland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, and the UK. These countries still conduct their stand-alone “bespoke” national surveys. By now, so too do many other countries, for example, New Zealand, Belgium, Denmark, Italy, Sweden, and South Africa. The surveys are done on a regular basis, although not necessarily every year. In some countries, victimization questions have been added to other generic household surveys (France, Ireland, Italy, and Romania are examples). In other countries, the ICVS has been adopted as the national survey, using augmented samples (Argentina, Estonia, Poland, and Japan are examples).

In many countries, household victimization surveys have been complemented by surveys focusing on special groups or particular forms of victimization. Violence against women (VAW) surveys are particularly popular, since “general purpose” household surveys are not considered to give good measures of sexual or assaultive victimization, which often involves offenders whom the victim knows. VAW surveys are notable for their differences in approach and have thus produced widely different estimates of harm to women (see, e.g., Percy and Mayhew 1997). Of increasing interest are ethnic minorities as victims of crime, the key issue being whether their different experiences are due to racial prejudice or to broader structural factors which negatively influence victimization risk. Business (or commercial) victimization surveys are also becoming popular. The types of business sectors looked at vary, although retailers and manufacturers have been a common focus. Recently, there has been some activity in terms of measuring cybercrime (or “e-crime”) among businesses.

The ICVS

The ICVS has been by far the most serious attempt to obtain a survey-based measure of victimization in a wide range of different countries. It was set up at the end of the 1980s by a small group of academic criminologists (the two authors among them) who were keen to apply survey methodology to explore international comparisons of crime. All the early ICVS academics (along with many others) were clear that using police statistics for international comparisons was fraught because of differences in legal definitions, police recording practices, and the readiness of victims to report to the police. They were also aware that results from bespoke victimization surveys were extremely difficult to compare on account of design differences – in particular, with regard to the questions on victimization and procedures for counting it. The thrust of the ICVS, therefore, was to standardize design and use the same questionnaire and analysis methods to produce equivalent across-country results.

The first ICVS took place in 1989 in 13 industrialized countries (see Van Dijk et al. 1990). It was then repeated in 1992, 1996, 2000, and (with different management procedures) in 2004/2005. Another set of surveys, which have been called ICVS-II, were carried out in 2010 in six countries, and these are returned to. The ICVS was also repeated in 2010 in Estonia, Georgia, and Switzerland.

Some of the initial 1989 survey countries took part again in subsequent rounds, although not all of them. Other new countries joined. To help consistency, much of the data collection in each of the five main rounds of the ICVS was supervised by one polling company. In the first four rounds, survey coordinators were appointed in each country to liaise with the central team to minimize deviations from the central ICVS model (or “template”). From 2000 onwards, efforts were made by the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) in Italy to execute surveys (usually at city level) in countries in transition and developing countries (see Gruszczyn´ ska (2004) and Alvazzi del Frate (1998) for results). Western industrialized countries have largely paid their own way in the ICVS, whereas others have had financial support. The cost of financing the ICVS has been a major factor in adopting rather modest sample sizes. The template was that national samples should cover at least 2,000 randomly chosen respondents (aged 16 or more), although some countries increased sample size to aid better local measurement. The issue of sample sizes in the ICVS is returned to.

The fifth round of the ICVS in 2004/2005 was organized rather differently. The first was the European Survey on Crime and Safety (EU ICS) in which all the 15 current member states of the European Union (EU) took part. This was organized by a consortium led by Gallup Europe and financed by the European Commission. Results are in Van Dijk et al. (2007). The second set of surveys was done in countries outside the EU, coordinated by the UN. Van Dijk et al. (2008) report on the results for all countries, in and outside the EU. All told, 30 countries were covered at national level, with another 33 surveys in main or capital cities.

Across all rounds of the ICVS over a period of two decades, more than 140 surveys have been done in over 80 different countries (with national-level surveys in 37). Over 320,000 respondents have been interviewed with a questionnaire that has been translated into 30 or more languages. The full dataset can be consulted at http://rechten. uvt.nl/icvs/ICVS2005_3full.zip (last accessed 11.07.2010).

Other Comparative Surveys

Before the ICVS began, there were a few attempts at cross-national comparisons using victimization surveys. Some studies took results from stand-alone national surveys, but they largely ran into the sand because the victimization count was so heavily influenced by survey design and counting protocols (cf. Lynch 2006). A few studies mounted standardized surveys in a limited number of countries, for instance, in Scandinavia. These exercises have largely sunk into obscurity.

Apart from these early studies and the ICVS, there are some other recent comparative surveys worth documenting.

- In 1996, Eurostat (the statistical arm of the European Commission) piloted a small Eurobarometer of Crime (covering the populations of the EU member states). It included questions about victimization experience, with small samples of 1,000 in most countries (Van Dijk and Toornvliet 1996).

- As part of the ICVS program, a comparative International Commercial Crime Survey (ICCS) was mounted in eight countries in 1994, although problems of different sector coverage and small sample sizes meant that little became of it. A similar questionnaire was later used in six other countries. It focused on experiences of business victimization, safety around the business area, pollution issues, and the extent and cost of security. The ICCS questionnaire was modified again by UNICRI in the late 1990s to include more items on fraud, corruption, extortion, and intimidation. Surveys took place in 2000 with small samples of 500 managers in eight capital cities in Central and Eastern European countries (Alvazzi del Frate 2004). There has also been a global, comparative survey of economic crimes against businesses, including cybercrime (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2005; Bussman and Werle 2006). This survey was repeated in 2011 for the sixth time among respondents from 78 countries.

- In terms of violence against women, a World Health Organization survey collected data between 2000 and 2003 from women in 12 countries, although there appears to be some differences in samples and survey administration (Garcia-Moreno et al. 2005). A tighter comparative exercise was the International Violence against Women Survey, which used a fully standardized questionnaire and analysis methods. Between 2004 and the end of 2005, surveys were conducted with women in eleven countries (see Johnson et al. 2008).

- The European Union’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) conducted pilots in six EU member states in the late 2006 and early 2007 to test different probability sampling approaches to identify selected ethnic minority and immigrant groups in countries where population data on minorities is often limited. The pilots were the forerunner to the European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey (EU-MIDIS) conducted in 2008 across the EU member states. The victimization questions were taken mainly from the ICVS questionnaire. Risks for ethnic minority residents were considerably higher than for others (EU-MIDIS 2009).

General Methodological Approaches

As said, the ICVS aimed for standardized methodology and questionnaire content. It built upon (and mirrors) some fairly generic features of victimization surveys. These are summarized below, with the ICVS put in context.

- Samples – Household victimization surveys generally adopt a stratified random sampling approach to achieve a representative sample in terms of age, gender, and geographical area. (Post-survey weighting is often done to improve representativeness.) Virtually all national surveys are cross-sectional (taking a different sample in each round). The ICVS has not deviated in these respects. Usually one person in each household is interviewed – and this was the case in the ICVS. This is generally someone aged 16 years or over (ICVS) or 18 years or over.

- Mode of interview – Interview modes have changed over time. Mail (or postal) surveys were a cheap option early on. These are now largely discounted mainly because of low (and probably unrepresentative) response – although Germany has recently conducted a postal survey in a pilot test for an EU-wide victimization survey that is discussed later. Face-to-face interviewing is still seen as the “gold standard” – because of higher response rates and the belief that they build more rapport with respondents. Face-to-face interviews now generally use computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) in which the questionnaire is programmed into a laptop which the interviewer uses to enter responses. Telephone interviewing has increased substantially as telephone coverage has grown. It was also boosted by methodological work that showed respondents willing to answer questions of a sensitive nature over the telephone (see Smith (1989) for an early test). Telephone interviews are now nearly always done through computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI), with samples typically drawn using some form of random digit dialling. The ICVS design “template” recommends CATI on cost grounds, although in countries where there is insufficient national telephone penetration, face-to-face interviews were conducted, generally with samples of 1,000–1,500 respondents in the main cities.

- The screening process – Respondents are screened for experiences of victimization over a given “recall period” (see below). The ICVS screener questions cover ten types of crime. The screener questions use definitions and concepts based on colloquial language rather than the law. In many surveys (the ICVS included), it is common for the selected respondent to answer questions about possible victimizations that can be seen as affecting the household as a whole (in the ICVS case: theft of a car, theft from a car, theft of a motorcycle or moped, theft of a bicycle, burglary, and attempted burglary). The respondent answers only about his/her experience in relation to theft of personal property, robbery, sexual offences and assault, and threats. (This is because it is felt that personal victimizations are not necessarily shared with other household members).

Screener questions usually aim to elicit a simple “yes” or “no” answer in the first instance, with further questions about the nature of what happened coming later. (This is because a respondent faced with a long list of questions immediately after saying “yes” may soon learn to say “no” to a subsequent screener.) The count of victimization sometimes comes from affirmative answers to screener questions (the ICVS procedure). Sometimes surveyors post hoc count and define the crimes using more detailed information about what happened.

While the focus of household victimization surveys is on “volume” crime, some surveys have also taken up issues of emerging interest. In later rounds of the ICVS, for instance, additional questions have been added on experiences with street-level corruption, consumer fraud (including Internet-based fraud), credit card theft, drug-related problems, and “hate crime”. Counts of these are usually not added to the conventional volume crime count.

- The recall period – Victimization surveys aim to estimate victimization over a limited time period. This needs to be short enough that experiences are reliably remembered, but long enough to generate an adequate number of victimization incidents to report upon. Most surveys have a “recall period” of 1 year. Some surveys (the ICVS included) initially ask people about possible victimization over the last 5 years and then focus down – for the main measurement – on the last 12 months, or (as in the ICVS) the last calendar year.

- Details of victimization – Many surveys follow up affirmative answers to the victimization “screeners” with detailed questions about what happened. In the case of the ICVS, details of victimization incidents are collected about the “last” incident of a particular type (the most recent incident of assault, for instance). This approach reduces interviewing time, although it may risk bias insofar as respondents choose a “last” incident which is most salient to them or about which they have more to say.

- Respondent information – All victimization surveys collect sociodemographic information to assess how risks for different groups vary. This includes age, gender, household income, and personal education level. Some surveys also try to measure “lifestyle” or “routine activities,” which the victimological literature has shown to be important in explaining why some people seem to be in the wrong place at the wrong time or behave in ways that “attract” victimization (e.g., Hindelang et al. 1978). The ICVS has made some small incursions here.

- Other crime-related information – Making contact with respondents is the biggest survey cost, so surveyors typically take the opportunity to ask them about crime-related issues, as well as victimization. The questions asked in different surveys have differed but popular topics which the ICVS has also covered include the use of crime prevention measures, attitudes to the police, fear of crime, and (to victims) the police response and the need for victim support.

General Limitations

There have been extensive discussions of the limitations of victimization surveys (e.g., Mayhew 2007). The brief review here applies to the ICVS and virtually all other surveys.

- Sample surveys do not represent the entire population as most sampling frames exclude those in communal establishments, for instance, and the homeless. This makes little difference to national victimization estimates, but it obviously precludes a full picture of victimization patterns.

- Findings are subject to sampling error. Margins of error are obviously greater for surveys with smaller samples. Estimates are most imprecise for crimes that happen relatively infrequently and for answers to questions answered only by part of the sample. The ICVS template, as said, was that national samples should cover at least 2,000 randomly chosen respondents (aged 16 or more). These are sufficient for “top-level” comparisons across different countries for broad categories of prevalent crimes. For very accurate estimates, and estimates for subpopulations, the ICVS struggles.

- Household victimization surveys omit “victimless” crimes (such as drug possession) and crimes against businesses and society at large. There are omissions even for crimes against private individuals. The victimization of children is largely ignored, and it is difficult to cover fraud well, since people will not always know they have been victimized.

- By no means all potential respondents can be contacted, and some who are contacted refuse to take part. Bias from nonresponse needs to be acknowledged, although its extent is somewhat contested. One view is that non-contacts and refusers may have “more to say” in victimization terms. The other view is that people who are available and willing to be interviewed are those who have “something to say.” This point is returned to in the context of the ICVS.

- There are other types of response bias too. Serious victimization incidents may be overcounted because of “forward telescoping,” whereas more minor incidents may well be undercounted. Incidents of a sexual nature and/or those perpetrated by someone well known to the victim are also likely to be undercounted – because they may not be perceived as “criminal,” or because respondents will be reluctant to talk about them. (As said, dedicated surveys are often seen as more suitable here).

- A further challenge is what is known as repeat or “series” victimization (such as domestic violence). It can be hard for respondents to remember series victimization as discrete events located accurately in time. Series victimization also poses a problem for “incidence rates” (the number of victimizations spread across a given number of respondents). Victims of series incidents often cannot count them reliably, and very high values, taken at face value, can distort victimization rate estimates for some groups. Reporting simple “prevalence rates” (the number of respondents victimized once or more in the previous year) is another option and one which the ICVS has generally taken (with the rates published with their margins of error at the 90 % confidence level).

Particular Challenges For The ICVS

Discounting the general limitations of household victimization surveys discussed above, a central question is whether the ICVS has achieved its purpose in terms of standardization and providing culturally relevant measures of crime.

The approach of the ICVS was that all countries should use the same questionnaire, adopt the same fieldwork period, and use telephone interviews. While much has been achieved here, the ICVS has fallen short of full standardization. This was especially so in the surveys in developing countries, where face-to-face interviews were mainly used, and sometimes less experienced interviewers. Marginalized groups living in informal housing were also hard to reach, as were the more affluent living in gated communities living in South America, for instance (Kury et al. 2002). While comparability may not have been seriously undermined, small differences in design and people’s response to the survey may have influenced ICVS results to some extent. Some of the main issues are set out below.

- The questionnaire. Country coordinators were responsible for ensuring that the initial English language questionnaire was well translated. In the first ICVS, all translations were back-translated and checked by the coordinating group, but back-translation did not always occur subsequently. Particularly demanding was translating the concepts and terms of the screener questions. Other questions and terms were also problematic. For instance, one question asked victims how “serious” they felt their crime had been, but the term “serious” proved difficult to translate. Other problems arose, for instance, with “stranger” (which in some countries is nearer to immigrant) and “bribery” (too serious a term in some countries for the type of lowlevel bribery the ICVS was trying to capture). On other fronts, too, it was inevitable that some countries baulked at the standardized questionnaire, feeling that “they could do better” or that some questions were inappropriate. Some countries were also keen to add additional questions or restructure the ordering of questions, thereby introducing possible “context effects.” Some made minor change to the ordering of response categories – causing huge complications in analysis.

- Response rates – These have been variable across countries and sometimes rather low. This was so especially in the first 1989 ICVS, when privacy regulations hindered sufficient recontacting of nonrespondents in some countries. Response rates generally improved subsequently, but then fell again in the 2004/2005 ICVS, reflecting a general trend in survey research. It may be that variable and low response affects ICVS results, although the extent of nonresponse bias is contested, as has been said. Analysis of results from the fifth ICVS also showed no statistical relationship in developed countries between the number of attempts needed to reach a respondent and overall victimization rates (Van Dijk et al. 2007). This suggests that reluctance to take part in telephone interviews may not have a serious impact on cross-national comparability. Whether this holds in developing countries is more arguable. The difficulties of contacting marginalized groups, or privileged groups, may mean that victimization rates in developing countries are underestimated.

- Mode of interview – An obvious challenge is whether ICVS face-to-face interviews produce similar results to those in CATI mode. Analysis of ICVS results so far has not indicated any systematic bias such that one mode produces higher victimization rates than the other (e.g., Scherpenzeel 2001). The burden of the methodological evidence is that survey productivity is most affected by quality control (e.g., the selection, training and supervision of interviewers).

- Cultural sensitivity – It is difficult to know whether people in different countries answer questions about victimization with the same degree of truthfulness. Different cultural thresholds for defining certain behaviors as crime may also apply, especially in relation to violent and sexual victimization. Rates of minor sexual victimization have typically been higher in Western countries where the social position of women is most advanced, suggesting that subjective thresholds are lower (Kangaspunta 2000). In pilot tests for the proposed European Security Survey (discussed later), there were high refusal rates in relation to sexual and intimate partner offences in some Eastern European countries specifically. Thus, there is still a question mark over how well a standardized survey can cope with cultural sensitivity in this domain.

- A rather different issue is whether any one survey can capture experience of and reactions to “crime across the globe.” One might suppose that the globalization of markets and mass media information has brought some attitudinal consistency as regards most conventional crime, especially in urban settings. Counter to this, though, is that there are inevitable limitations to the ICVS as a finetuned measure of the impact of crime. Despite much common ground in terms of people’s usual experience of victimization, some countries may have particular concerns which bespoke surveys could cover better. Questions on bribery and corruption, for instance, are very sensitive to different interpretations as to what they mean and how seriously they are assessed. In some former Soviet countries, street-level extortion in the form of neighbors asking to borrow money is a major concern.

What Has The ICVS Shown?

Space precludes documenting the full extent of ICVS results here. Just four sets of results from the ICVS are singled out. The first is what it has shown as to the level crime in different countries compared to the picture from police figures. The second concerns what ICVS measures of trends in crime show relative to trends according to police figures. The third set of results relates to reporting behavior and assessments of police performance and the fourth to victims’ assessments of the seriousness of crime across different countries.

ICVS And Police Measures Of Crime

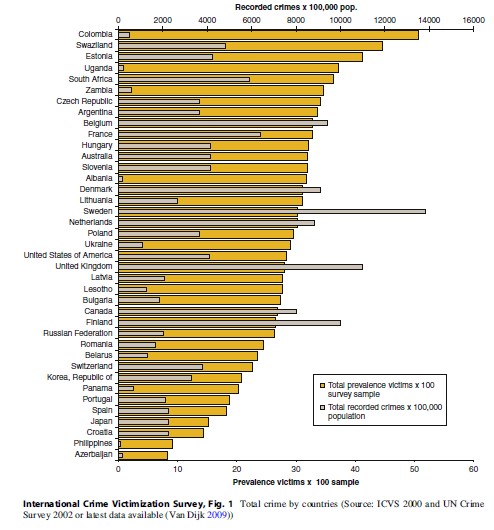

Van Dijk (2009) looked at 39 countries across the world in relation to “total ICVS crime” (as measured mainly in 2000) and “total police-recorded crime” around the same period (drawing mainly on the 2000 UN Crime Survey, which collects a range of criminal justice statistics). Figure 1 shows the results. “Total ICVS crime” is generally more restricted in scope than “total recorded crime,” with the result that in some countries (Sweden, the UK, and Finland, for instance), total recorded crime per capita is higher.

Figure 1 shows no correlation between the actual level of victimization and the rates of crime recorded by the police (r ¼ 0.212; n =39; n.s.). Some countries with exceptionally high recorded crime also show a comparatively high victimization rate (South Africa), but many others do not (e.g., Finland, Canada, and Switzerland). Comparisons between country rankings according to the ICVS and police figures were repeated for different types of crime. The results showed positive correlations for robbery (r=0.663, n =37), and theft of cars (r=0.353; n=34), but much weaker (and statistically insignificant) correlations for other types of crime.

Trends In Crime

Of the countries which have taken part in the ICVS since 1989, there are 15 developed countries about which information is available from at least four different rounds, enabling an analysis of trends in crime over the last 10–15 years. The average victimization rates for these countries showed them to have peaked halfway the 1990s but declined since. The pattern for individual countries was nearly always the same. The drops are most pronounced in vehicle-related crime and burglary.

In looking at trends in crime, Van Dijk and Tseloni (2012) used results from countries that had taken part in four or five rounds of the ICVS between 1989 and 2004/2005. Rates of overall victimization in North America (Canada and the USA), Australia, and the nine European countries for which ICVS-based trend data are available show distinct downward trends. The drop in crime in the USA was already evident between the 1989 and 1992 ICVS rounds. The turning point came somewhat later in Canada, most European countries, and Australia. Trend data were available from only two middle-income cities in the developing world, but these also point at a downturn in overall victimization since 1996 (Buenos Aires) or 2000 (Johannesburg). In a separate analysis, Van Dijk and Tseloni centered on ten European countries, of which four had data until 2010 from the ICVS-II (see below). In all the countries except Belgium, rates of victimization in 2005 and/or 2010 were significantly lower than those of about 10 years before.

The purpose of Van Dijk and Tseloni’s (2012) examination of trends in crime was not simply to focus on the ICVS. They also looked at surveymeasured trends from a number of stand-alone national surveys, as well as the police figures in the countries that ran those surveys. Nonetheless, there are points worth noting from an ICVS perspective. First, Van Dijk and Tseloni note the fortuity of the ICVS being initiated in time to register the rise in volume crime, its general “peaking” around the mid-1990s and its subsequent decline since. Second, the ICVS covered a wider range of countries than alternative standalone survey counts did. Third, across this broader range of countries, the ICVS offered a picture of crime trends to compare with police figures. The fact that police figures could have their own momentum in registering changes in crime levels – due to changes in recording procedures or the scale and effectiveness of policing activities – bought the ICVS into play. It would not be fair to say that the ICVS holds credit for the criminological “bombshell” of a fall in crime in many countries in recent years. But in helping to document this, it has greatly added to the case that parochial (national) popular explanations of the fall in crime – such as policing improvements, greater imprisonment, or economic conditions – are not adequate.

Reporting And Police Performance

The ICVS measures levels of reporting to the police to see the extent of differences across countries and whether these help explain variations in police figures at country level. Without going into detail, suffice it to say that fairly marked differences in reporting levels emerge. There are generally higher rates in more affluent countries but still differences nonetheless. Referring back to the data on which Fig. 1 is based, the concordance between policerecorded crime and a measure of ICVS crime reported to the police was rather closer than was the case for police-recorded crime and all ICVS crime. This is important testimony to the fact that victims’ reporting habits are one factor influencing the officially recorded output of police forces.

Although the decision to report a victimization has been shown to be mainly driven by a simple cost-benefit assessment, it also serves to some degree as a measure of confidence in the police. Using data from the ICVS 2000, Goudriaan (2004) found that country-level variations in reporting property crimes were related to confidence in local policing (among victims and nonvictims). Van Dijk et al. (2008) also showed an interrelationship between levels of reporting, confidence in local policing and – a third factor – the degree to which victims who did report felt satisfied with the police response. A “police performance” indicator based on the three measures showed that the police performance was perceived to be best in Northwest Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Scores on the index were lowest for Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Estonia, Turkey, Cambodia, Greece, and Poland.

The Seriousness Of Crime

As said, a challenge for the ICV is how far results might be affected by cultural differences as regards the meaning of victimization and responses to it. One result at least that undermines such concerns relates to victims’ assessment of the seriousness of what happened to them – which they were asked to rate on a three-point scale. Van Dijk (1999) looked at results based on the 1992 and 1996 ICVS in relation to 14 types and subtypes of crime in countries grouped into five regions. Because of possible translation differences in the connotation of “serious,” mean scores were translated into rank numbers per region. There was a striking similarity in the ranking of the crime types in terms of seriousness. Regression analysis also showed that seriousness ratings were determined much more heavily by crime type than any social characteristic of the victim. That said, there were a few differences. Motorcycle theft, car theft, and joyriding ranked highest in seriousness in developing countries but rather lower elsewhere – no doubt reflecting different economic values of cars and motorcycles. In the Nordic countries where levels of violence are comparatively low, simple assaults and threats are considered as more serious than elsewhere. In terms of victim characteristics, after controlling for crime type, gender was the strongest predictor of how seriously crimes are judged – with women considering crimes somewhat more serious than men.

Conclusions

Victimization surveys are now firmly established in criminological research. Surveys comparing the level and nature of crime internationally are a rather newer enterprise than stand-alone national surveys, although the ICVS started over two decades ago. It came into its own because of growing recognition of the difficulties of comparing police figures. This was something of a kiss of death for traditional comparative criminology, although it is fair to acknowledge improvement of late in exposing the problems of noncomparability. For instance, the European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics now itemizes the difference in legal definitions, counting protocols, etc. that affect police statistics (Aebi et al. 2006).

While the ICVS has not provided impeccable or comprehensive data by any means, it has arguably improved on what can be gained from police records as regards comparative levels and patterns of victimization in different parts of the world. It has also offered an important addition to the picture from police records on trends in crime.

While the ICVS has shown that it is feasible to conduct standardized surveys in a large number of countries, it nonetheless carries several practical lessons. Conducting surveys in a standardized way, more or less on time, and with sound adherence to the ICVS template posed a considerable logistical challenge. Tight oversight from the central team was needed to ensure that country coordinators engaged with tedious technical detail to maintain consistency. Financial matters were time consuming and challenging, especially with regard to developing countries. Moreover, there were occasional issues as regards ownership of results. When and how these were released was also a minefield – as crime “league tables” are politically sensitive. For countries taking part that had their own national surveys, country coordinators also sometimes needed to be able to explain why the ICVS could give different results as to victimization risks.

Future Developments

Policy interest in international comparisons of crime using victimization surveys has been enhanced by the results to date. Thus, countries are likely to be keen to enter into future comparative survey exercises – especially if fieldwork costs are met. But even where self-funding is necessary, countries that have not taken part in a standardized survey to date may want to sign up, particularly when they have insufficient resources for a bespoke national survey. This makes it attractive for them to take a ride on the back of another survey vehicle, especially when comparisons with other countries are on offer. A striking example of this are the repeats of nationwide surveys based on the ICVS in Georgia in 2010, 2011, and 2012 which have demonstrated a very significant drop in crime (Van Dijk and Chanturia 2011). An abridged version of the ICVS has also been used in 2012 in Moldova and Azerbaijan and is being pilot tested in Tamil Nadu, India. This said, the conduct of victimization surveys in developing countries seems to have stayed somewhat behind. This is unfortunate since in many of these countries, crime remains a major concern and statistics of recorded crimes are of poor quality, if they exist at all.

The logistical challenges of mounting comparative victimization surveys remain. So too do the methodological challenges of improving crime measurement internationally through survey techniques that are hard to standardize in diverse environments. “Survey saturation” in Westernized countries may also become an issue, whatever mode of interviewing is adopted. Over the lifetime of the ICVS, the development of CATI has reduced fieldwork costs and helped consistent questionnaire administration. Now, though, many people (particularly more heavily victimized younger ones) rely only on mobile phones. A key issue is whether viable representative samples can be obtained with the growing diversity of telephone provision – although survey companies will be under strong commercial pressure to achieve a solution. The inclusion of mobile phone users in sampling designs is an obvious priority.

As Internet use grows, computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI) offers a way forward for surveys in the future, with cost advantages. Pilot testing with CAWI for the national victimization surveys in the Netherlands and Finland has begun, with fairly encouraging results. However, the methodological challenges of CAWI include possible bias due to differential Internet access, a degree of respondent self-selection, and low response rates. In the medium to long term, ways round these problems may be found, particularly by using incentives and representative panels that polling companies are increasingly likely to offer.

What of initiatives currently in place for further international comparative surveys? At present, there are no elaborate plans to repeat the ICVS globally in either of the two forms it has taken in the past – i.e., with a largely academic input or (as in the fifth round) with both an academic and EU input. However, there have been other developments afoot – albeit with a less global focus – which have taken or are taking forward comparative survey-based measures of victimization in different countries.

ICVS-II

The first initiative – the so-called ICVS-II – replicated the ICVS with a reduced questionnaire and across a broader range of interviewing modes. An initial plot was conducted in 2008 by a Dutch agency, NICIS, at the request of the International Government Research Directors (IGRD). NICIS commissioned pilots in Canada, Germany, Sweden, and England/Wales. NICIS subsequently mounted a round of surveys in 2010 with co-funding from the European Commission. Six countries took part: the four who participated in the first pilot, together with Denmark and the Netherlands. The questionnaire used in the first pilot was amended somewhat. Each country was to provide a net sample of 4,000, half of which was to be achieved using CATI and half through CAWI (this split between a register of personal data and addresses’ and a “panel”). Results are available on the NICIS website, differentiating between CATIand CAWI-based results (http://62.50.10.34/icvs/).

European Union Safety Survey (EU-SASU)

A second initiative, led by Eurostat, is a standardized household victimization survey – the EU Safety Survey. At the time of writing, this is planned to take place in 2013 or 2014 in all 27 member states. The survey can be seen as an extension of the EU’s sponsorship of the 2004/ 2005 ICVS. It is intended to meet the perceived need for a full EU-wide comparative survey tailored to the current legal and social realities of the EU and its particular policy interests. The results will complement the numbers of crimes recorded by the EU member states annually published by Eurostat.

In 2009, the Universities of Tilburg and Lausanne were contracted by Eurostat to evaluate pilot tests in 17 member states using a draft questionnaire prepared by the European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI). The pilot was to assess the questionnaire using different modes of interview, and recommendations were to be made in the light of results as to the best way forward. In the event, the piloted questionnaire proved problematic in the field on several fronts. Moreover, a subsequently revised version (trying to maintain some comparability with a set of core questions from the ICVS) did not entirely meet the approval of the survey agencies in all countries either – testimony to the difficulties of gaining consensus when jurisdictional sensitivities and interests differ. One difficulty has been the degree of stringency that can be imposed as regards interview mode. Although standardization is highly advisable (with CATI currently still the best option), dictating a common mode is unrealistic given different survey capabilities in different countries. There is also pressure from some countries to bypass the EU Safety Survey and provide “adjusted” results from their own large-scale national surveys instead – a procedure that may prove tricky to say the least.

European Union Crime Against Businesses Survey

The EU is also testing whether to take forward standardized, comparative surveys to assess the crimes against businesses in the 27 EU member states and the now three candidate countries. Pilot work started at the end of 2011, led by Gallup Europe in collaboration with Transcrime (in the Universita` Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan). Large pilot surveys are being conducted in 20 of the EU member states, encompassing interviews with 19,000 businesses. A two-stage approach is being tested to minimize nonresponse. The first CATI stage gather information about locality and business activity, and it will screen for the prevalence and incidence of victimization of selected types of crime. In the second stage, CAWI will mostly be used to contact businesses that had reported victimization to collect more details of what happened.

European Union Agency For Fundamental Rights (FRA) Violence Against Women Survey

In 2012, the FRA conducted an EU-wide survey of violence against women. Led by HEUNI and UNICRI, this encompassed interviews with 40,000 women across the 27 EU member states and Croatia (a candidate country). The survey used standardized face-to-face interviews with about 1,500 randomly selected women in each country. (A pretest took place in six EU member states to test the survey questions). The interviews covered women’s so-called “everyday” experiences of violence (including physical, sexual, and psychological violence, and harassment and stalking) by current partners, former partners, and non-partners in the past 12 months and since the age of 15. The survey also covered experiences of violence before the age of 15, to give a “lifetime” perspective. The aim is to compare the frequency and severity of violence against women in the different EU countries, including their access to and experience of police, healthcare, and victim support services. First results are expected in 2013.

Bibliography:

- Aebi M, Aromaa K, Aubusson de Cavarlay B, Barclay G, Gruszczynska B, von Hofer H, Hysi V, Jehle J-M, Killias M, Smit P, Tavares C (2006) European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics 2006. http://www.europeansourcebook.org

- Alvazzi del Frate A (1998) Victims of crime in the developing world. UNICRI, Rome, Publication 57

- Alvazzi del Frate A (2004) The international business survey: findings from nine central-eastern European cities. Eur J Crim Policy Res 10:137–161

- Bussman K-D, Werle M (2006) First findings from a global survey of economic crime. Br J Criminol 46:1128–1144

- EU-MIDIS (2009) European union minorities and discrimination survey: main results report. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (fra.europa.eu/eu-midis)

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen H, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C (2005) World Health Organisation multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. World Health Organisation, Geneva

- Goudriaan H (2004) Reporting to the police in western countries: a theoretical analysis of the effects of social context. Justice Q 21(4):933–969

- Gruszczyn´ ska B (2004) Crime in central and eastern European countries in the enlarged Europe. Eur J Crim Policy Res 10:123–136

- Gruszczynska B, Gruszczynski M (2005) Crime in enlarged Europe: comparison of crime rates and victimization risks. Transit Stud Rev 12:1337–1345

- Hindelang MJ, Gottfreson MR, Garofalo J (1978) Victims of personal crime: an empirical foundation for a theory of personal victimization. Ballinger, Cambridge, MA

- Kangaspunta K (2000) Secondary analysis of integrated sources of data. In: Alvazzi del Frate A, Hatalak O, Zvekic U (eds) Surveying crime: a global perspective. ISTAT/UNICRI, Rome

- Johnson H, Ollus N, Nevala S (2008) Violence against women. Springer, New York

- Kury H, Obergfell-Fuchs JM, Wurger M (2002) Methodological problems in victim surveys: the example of the ICVS. Int J Comp Criminol 2(1):38–56

- Lynch J (2006) Problems and promise of victimization surveys for cross-national research. In: Tonry M, Farrington D (eds) Crime and justice: an annual review. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 229–287, Volume 34

- Mayhew P (2007) Researching the state of crime: national and international and local surveys. In: King R, Wincup E (eds) Doing research on crime and justice, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Percy A, Mayhew P (1997) Estimating sexual victimisation in a national crime survey: a new approach. Stud Crime Prev 6:125–150

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (2005) Global economic crime survey 2005. In collaboration with Martin Luther University

- Scherpenzeel A (2001) Mode effects in panel surveys: a comparison of CAPI and CATI. Bundesamt fu˝ r Statistik, Neuenberg

- Smith MD (1989) Women abuse: the case for surveys by telephone. J Int Violence 4:308–324

- Van Dijk JJM (2009) Approximating the truth about crime. www.crimprev.eu

- Van Dijk JJM (2008) The world of crime; breaking the silence on problems of crime, justice and development across the world. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Van Dijk JJM (1999) The experience of crime and justice. In: Newman G (ed) Global report on crime and justice. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 25–41

- Van Dijk JJM, Chanturia T (2011) The remarkable case of Georgia. Ministry of Justice of Georgia, Tbilisi

- Van Dijk JJM, Tseloni M (2012) International trends in victimization and recorded crime. In: van Dijk JJM, Farrell G and Tseloni M (eds) The international crime drop: new directions in research. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

- Van Dijk JJM, Manchin R, Van Kesteren J, Hideg G (2007) The burden of crime in the EU: a comparative analysis of the European crime and safety survey (EU ICS) 2005. Gallup Europe, Brussels, http://www.europeansafetyob servatory.eu/downloads/EUICS_The%20Burden%20of%20Crime%20in%20the%20EU.pdf. Last accessed 11 July 2010

- Van Dijk JJM, Mayhew P, Killias M (1990) Experiences of crime across the world: key findings of the 1989 international crime survey. Kluwer, Daventer

- Van Dijk JJM, Toornvliet LG (1996) Towards a Eurobarometer of public safety. Paper presented at the seminar on the prevention of urban delinquency linked to drug dependence. European Commission, Brussels, November

- Van Dijk JJM, Van Kesteren JN, Smit P (2008) Criminal victimisation in international perspective: key findings from the 2004-2005 ICVS and EU ICS. Boom Legal Publishers, The Hague, http://rechten.uvt.nl/icvs/ pdffiles/ICVS2004_05.pdf. Last accessed 11 July 2011

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.