This sample Intervention and Prevention in China Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

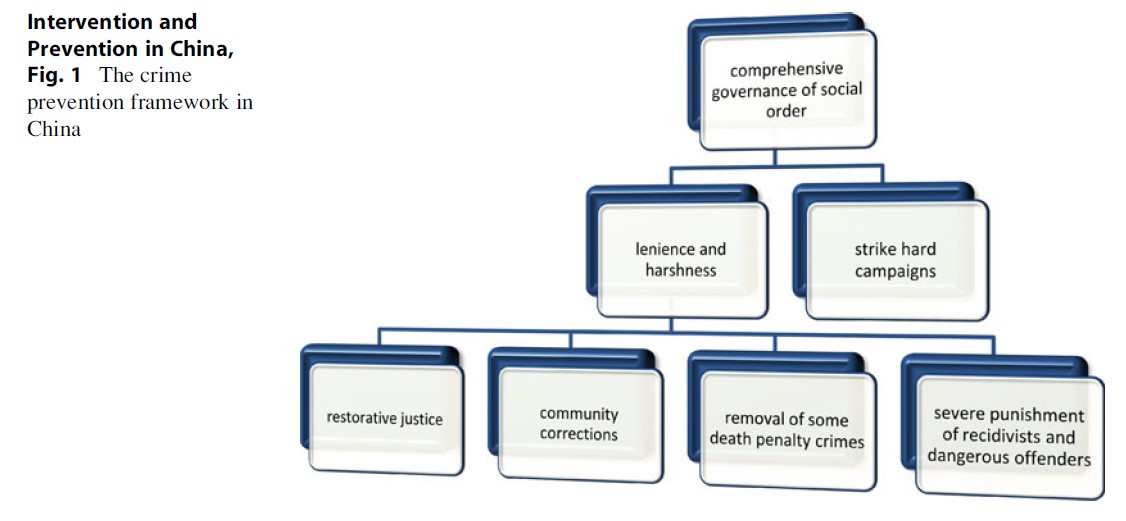

The key elements of the overall approach to prevention and intervention on crime in contemporary China are outlined in Fig. 1. The approach is best understood as state-initiated comprehensive management or governance of social order. Developed in the new era of economic liberalization and reform, the policy of comprehensive governance was first promulgated in 1981 as a key organizational tool for crime control but only legislated for in 1991 (Situ and Liu 1996a). The approach emphasizes prevention, education, and punishment of offenders through coordination and cooperation between political, legal, educational, cultural, economic, and social bodies yet sits in an integrated manner alongside “strike-hard” campaigns by police against more serious and organized crime (Jiang and Dai 1990; Situ and Liu 1996a; Zhong 2008). While the development, nature, and dynamic interplay between these elements can only be fully explicated through detailed sociohistorical analysis, this research paper describes and contextualizes the relevant organizational and thematic issues contained within the comprehensive approach to the prevention and intervention on crime, including the complex relationship between public and private agencies in prevention and intervention on crime in China.

Introduction

In 1962, Leifeng, a Chinese People’s Liberation Army soldier, died; he was decorated by the state for his exemplary kind deeds. His helpful actions were universally acknowledged, and the month of March was designated as the month of “Learning from Leifeng,” when everyone was encouraged to follow the example of Leifeng and undertake helpful and kind actions (Bakken 2000). Fifty years on, modern socialist China is both a very different yet similar place. At the societal level, a depoliticized place; yet in terms of the language of governance, including management of crime, familiar (Dutton 2005: 252–255). In the social control mechanisms of contemporary China, “exhortation through example” and mass participation are still regarded as key tenets by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (Bakken 2000; Chen 2004). Social order in China is supposed to be maintained by the capacity of society’s members to understand one another and to act in concert in achieving common goals through common rules of behavior. The most important distinction is the efforts of the Chinese state to control both the behavior and the minds of the people (Wilson et al. 1977). Social conformity in the Chinese vocabulary is not limited to behavioral conformity with the rule of law but always moralistically identifies with the officially endorsed beliefs of social standards and behavioral norms. The Chinese tradition, both before the creation of the People’s Republic (in 1949) and since, is that of “greatest unity” of society (Ren 1997). Thus, the current crime prevention framework known as “comprehensive governance (or management) of social order” takes crime as caused by a complex set of psychological, social, and economic factors and to be prevented and “cured” by a similarly rich interplay of state mechanisms.

The policy of comprehensive governance of social order adopted since 1991 is, in essence, traditional strategies with new components: thus, it continues the Maoist ideology of the state as “moral entrepreneur” (Wilson et al. 1977), combined with formal and informal mechanisms; the policy continues with the perceived need to develop citizens’ knowledge about laws in the Republic; it revives the Maoist “mass line” – listening to the ideas of the people and the ruling party working with them (Dutton 2005); finally, it continues to promote lenience and recognizes the importance of rehabilitating offenders through correction while adding a bifurcatory “harsh” aspect – namely, that of severely punishing recidivists and organized criminals through long prison sentences and via the death penalty if required (Liang 2008). These key themes are enlarged upon in what follows.

Key Conceptual And Organizational Themes

Along with modernization, crime rates have risen significantly in China’s cities over recent decades (Liu 2005). While there has been no nationallevel victimization survey in China, there is city-level data from the key city of Tianjin, where estimates on risk of major crime types are available to scholars (Zhang et al. 2007a). Surveys of this type in China are not without research challenges and concerns, for example, around gaining access, designing and deriving samples, protecting privacy of respondents, and ensuring data integrity and quality (Zhang et al. 2007b). Crime is now, to use David Garland’s term, a “normal social fact” in urban China (Garland 2001). A fellow traveler alongside economic development has been insecurity, built into the fabric of everyday life. Crime has increasingly become a daily consideration for anyone who owns property or uses public spaces in urban China. People have felt the need to establish control over risks and uncertainties, and the desire to assuage feelings of insecurity has become ever more urgent. For the Chinese Communist Party, the increasing crime rate has posed a threat to the legitimacy and stability of its rule, and social order has become a major government concern (Dutton 2005; Muhlhahn 2009). As originally developed in the 1980s, one key organizational theme within the policy of comprehensive governance is to engage in so-called “strike-hard” anticrime campaigns. This prong of the policy focused on attacking crime directly, as opposed to the longer-term goal of prevention and social reintegration of offenders. “Strike hard” has been described as an extreme form of the educative and deterrence function of punishment used as a method of crime prevention and social control. It is essentially a policy of employing severity and swiftness to deal with criminal cases considered to be a major threat to public or social order (Trevaskes 2007a, b). “Strike-hard” anticrime campaigns take two forms. One is the large-scale campaign that runs for up to 3 years, focusing on a variety of crime targets chosen by the state. The other is the “specialized” smaller-scale campaign targeted at one category of crime. Party authorities initiate both the national campaigns and the specialized anticrime drives, which are run under the leadership of Party committees and criminal justice personnel at provincial, municipal, and local levels. Campaigns against organized crime and drug crime are well described in recent literature (Trevaskes 2007a, b, 2008). Police, prosecutors, and courts work together to ensure swift arrests, swift prosecution, and swift and severe punishment for the targeted types of crime that the authorities identify. “Severity” limits judges’ discretionary power and requires them to punish relatively harshly. “Speedy” investigation, prosecution, and adjudication of cases to deal efficiently with identified criminals, often within several days of their arrest, distinguish these campaigns from the usual criminal justice process (Muhlhahn 2009). “The People’s War on Drugs” is a major specialized campaign that operated as the drug crime counterpart to an existing campaign against organized crime (Trevaskes 2008). It was launched in mid-2005 and exemplifies comprehensive management of social order as an approach to crime fighting through interagency cooperation between the criminal justice agencies. It is the latest in a long succession of antidrug campaigns since the late 1980s and is China’s key countermeasure against an alarming rise in heroin use. The core strategy is to block the sources of drugs and stop their circulation. The national modus operandi of the campaign in its first year was to separate tasks across individual agencies rather than to use a multiagency method. Individual agencies included customs, railways, water police, airline security, forestry police, and the postal services.

Criticisms of “strike-hard” campaigns abound in the Chinese literature (see Trevaskes 2007a, b for details). Among senior policy makers and senior administrators, anticrime campaigns are overwhelmingly supported, but among practitioners, there is greater ambivalence and criticism. Problems identified in the Chineselanguage literature include the difficulty of control and accountability where criminal justice agencies overstep the mark in campaigns, that like cases are not treated alike in terms of severity across place and time, and the problems of confusion on the ground as different agencies compete to “deliver swift justice.” Many Chinese scholars question the overall effectiveness of the strike-hard policy (see Trevaskes 2007a, b). Apart from no significant reduction of crime rates following the campaigns, there are criticisms of the lack of long-term prevention effects (Liang 2005). However, some research argues that the anticrime campaigns have significantly impacted on lowering serious crime (Chen 2012). In this regard, it is interesting to note that the recent fourth “strike-hard” campaign in 2010 targeting two types of criminals – violent criminals (esp. with gun and organized criminals) and so-called “mass-hatred” criminals (including telephone fraudsters, children and women traffickers) – has been remarked upon more favorably by commentators. Unlike previous campaign waves, the police this time were focusing more on prevention – for example, increased patrol, problem-oriented policing, and mediating community conflicts rather than arresting and delivering severe and swift punishment (Yang 2010).

As an element of the comprehensive governance of social order, “strike-hard” campaigns draw from deep cultural wellsprings, and any adequate understanding of why such a practice is continued, despite what appears to be very limited success, needs to recognize how the practice partly reflects the remnants of classic Maoist “mass-line” thinking: the categorization and targeting of specific criminal types and defining social harm according to the socialist social relations violated an important aspect of Mao’s early campaigns against “political enemies,” the flexible nature of administration of law in practice during campaigns, and finally the educative role performed by state agencies (police, prosecution, and courts). In essence, the “strike-hard” campaign performs a number of noninstrumental, expressive political functions for the ruling Party (see Liang 2005). Thus, short-term severe strike campaigns became an indispensable complement to decreasing traditional mass-line neighborhood-level preventive control. This leads to a second key theme within the comprehensive governance of social order, namely, mobilization of broad preventive forces, particularly at neighborhood (community) level.

The origin of mobilization lies in the working style of the early Chinese Communist guerilla movement of the 1930s, linking popular participation with the guerilla struggle (see Selden 1971). Mao framed it in the following terms, “.. .take the ideas of the masses and concentrate them, then go to the masses and propagate and explain these ideas until the masses embrace them as their own.. .” (Mao 1967, vol 3, 119). In the Mao period, the Chinese peasant was mobilized out of any passive role into willing, positive, active participation based not on broad notions but on a single commitment to the total social and economic transformation of society. Campaigns were highly organized mobilizations of mass commitment to push over barriers to proletarian dictatorship and socialism, and mass-line thinking has continued to echo throughout the post-Mao period. Wang (1989) sets out the theory of comprehensive governance and basic rationale for the revival of somewhat moribund mass-line security organs and renewal of community activism under Party committee leadership. In this context, commentators point to the pioneering role of the Fengqiao district in Zhejiang province, where in the early 1960s local mass democracy was put into effect, illuminating how long-term effective crime prevention role relies upon taking wider administrative measures (Dutton 2005).

Under the 1991 law on comprehensive governance, all government organizations at different levels regard taking comprehensive measures to secure prevention as one of the most important duties, with an appropriate responsibility system for management; it is also accepted that it is imperative to mobilize and rely on the broad mass of ordinary people in the community. Within urban environments, the “subdistrict” level typifies how these arrangements are structured. For example, in Shanghai, the subdistrict would have an office of comprehensive management and a community structure would contain members of the residents’ committee, community police, property owners, housing management, private security personnel overseen by the police together with social workers responsible for meeting the needs of local offenders, and finally local volunteers who are usually retired and receive small financial subsidies. Financial support and human resources are underpinned by government spending. Emphasizing nonlegal methods to solve neighbor disputes is another key characteristic of the comprehensive approach. People’s mediation is a process whereby the parties concerned to a dispute seek to reach a mediation agreement on the basis of equal negotiation and free will and thus solve the dispute between them, and the mediation agreement reached upon mediation is binding to all parties concerned, and the parties concerned are asked to fulfill it as agreed. There is a mediation committee as part of every residents’ committee (Hong 2011). Since the 1990s, people’s mediation has faced some unprecedented challenges. Along with rapid social changes, China’s dispute resolution system has gone through significant transformations. Courts have increasingly been favored by the public as a forum to solve disputes. In 1990, the people’s courts handled about 1.8 million civil lawsuits. This number jumped to 3.4 million in 2000, a nearly twofold increase. Meanwhile, the numbers of mediation committees and disputes solved through mediation have declined steadily. In 1990, there were approximately 1 million mediation committees that solved 7.4 million disputes. In 2000, these numbers dropped to 960 thousand mediation committees that solved 5 million disputes (Hong 2011). In the 1980s, people’s mediation committees disposed of an average of almost 11 times more disputes than trial courts, but this ratio had decreased to 1:1 in 2001. In response, and as part of the comprehensive approach, the Chinese government has made significant policy reforms to revitalize mediation, during the Fourth National People’s Mediation Work Conference held in Beijing in 1999; the Ministry of Justice added an important phrase, “using multiple methods to solve problems,” to the original people’s guideline of “combining mediation and prevention, with prevention as the main goal” for mediation. The Ministry called for people’s mediation committees across the country to gain cooperation and resources from administrative and judicial organizations to expand the range of disputes that can be solved by mediation (Hong 2011).

Details of the practice of the comprehensive approach to prevention can be gleaned from research studies on Guangzhou and Shenzhen (Situ and Liu 1996b; Zhong 2008). In Guangzhou, government aimed for “the establishment of 1,000 security neighborhoods in which criminal events must be substantially reduced, the transient population must be adequately managed, and the public environment must be made safe and clean” (Situ and Liu 1996b: 95). Organizationally this involved establishing the coordinating Office of Comprehensive Management which ensured coordination of crime prevention, monitored the level of transient population, and developed environmental schemes; it is a well-developed contractual responsibility system – contracts not only clearly define responsibility but also make security a responsibility that is legally binding on all people involved. Failure to meet the conditions of the contract can result in administrative penalties, such as resignation or dismissal, or financial punishments, such as a fine or elimination of bonus. Those who are responsible for the occurrence of serious criminal incidents are also subject to criminal charges. By linking the security duties to individual interests, the system of responsibility effectively promotes the motivation of contractees and improves the quality of their performance in carrying out preventive duties. Patrol-based neighborhood teams were also established, with volunteers receiving some training and augmenting police patrol. Linked to this was police-initiated “anticrime” campaigns against specific crimes (as described earlier in this research paper). Finally, situational measures were implemented, including “gated” entry and the securing of ground floor apartments with “bars-to-windows”.

In Shenzhen, five neighborhoods were studied to examine the practice of comprehensive governance (Zhong 2008). Shenzhen local government sought to develop “little safe and civilized communities” (LSCC). In terms of safety, residents should feel safe, with few serious crimes and general public security cases kept under control. In terms of civilization, active politics, economy, culture, education, hygiene, and so on were required. Thus, in an LSCC in Shenzhen, there must be a strong conformity to law and regulation, good public order, high degree of civilization, upright social morale, beautiful environment, and harmonious neighborhood relationship. Piloting of schemes began in 1992 and took place over a number of years, with full development in 1998. For a little community to be eligible for LSCC, it has to meet these criteria and go through a complicated rating process. The rating categorizes the communities into “exemplary,” advanced, pass, or failure, on an annual basis. If a community fails to meet the standards in the second year, it is stripped of the original level. It can also strive to upgrade to a higher level in subsequent years. The important measures in implementing the comprehensive approach to building such communities have four elements: organizational features (ideological underpinning, responsibility system, mass prevention and mass management, and fund raising), safety measures (police, private security, situational measures, and management of the transient population), civilization measures (moral education, promoting harmony, community development, and environment improvement), and of course the rating system itself.

A final significant theme in understanding the changing conceptual basis of contemporary crime prevention and intervention in China is that of the recent promotion of the idea of “balancing leniency and harshness”; this idea has been brought to bear in the areas of alternatives to normal punishment (restorative justice) and the death penalty in particular (Trevaskes 2010). Within the wider policy of comprehensive governance, this development has resulted in a redefinition and use of what are considered “serious crime” and “minor crime.” After 2006, a series of criminal justice reforms began to be publicized after President Hu Jintao espoused “building a socialist Harmonious Society” as the touchstone of the Sixteenth Party Congress governance objectives for the coming decade. These reforms were aimed at addressing the crucial political issue of encouraging social harmony by preventing further social conflicts during a period of accelerated economic and social transformation. In 2006/2007, the Chinese Communist Party used this policy as a rationale for momentous changes to the death penalty, thus the change in 2006, requiring the Supreme People’s Court to ratify death sentences, in contrast to the previous practice of allowing provincial courts this power. More recently still and in keeping with this shift, recent amendments to the Chinese Criminal Law in 2011 have removed the death sentence from many nonviolent economic crimes. In 2007, criminal justice authorities announced changes at the other end of the spectrum – moves to decriminalize a wide range of minor offenses and to encourage courts to use a greater variety of alternatives to custodial sentencing, such as restorative justice and involving community-based corrections. Restorative justice techniques are intended to provide assistance, guidance, and direction to residents who have committed minor offenses, have been caught by police agencies, or have been released from correctional institutions. Traditionally, these have been organized in the form of help groups that normally consist of the offender’s parents or relatives, a member of the neighborhood committee, and an officer from the neighborhood police station. Currently, social workers and volunteers are also likely to participate in such groups. The primary goal is to intervene in the lives of residents, especially young residents, who are at risk of becoming offenders and to reintegrate the ex-offenders back into the community. Nevertheless, restorative justice involving victims is not without its critics in China, where certain scholars have argued that it is immature and confused, incompatible with Chinese constitutional law (Zhao 2005). Application of community corrections, involving management of sentences outside of prison, is itself still “experimental” and is permitted in some 18 Chinese cities. A recent review of the scientific literature on community corrections in China highlighted a number of issues: the small number of recidivism studies following release from prison, a lack of reliable information surrounding recidivism rates in general, and very few studies comparing China’s particular circumstances with those of the West (Liang and Wilson 2008).

Conclusions

Research from the USA, Europe, and the UK suggests that community crime prevention transcends both situational and social prevention and indeed transcends the borders between developmental and situational prevention, with its focus on social relationships within and beyond individual communities (Ekblom and Pease 1995). In the West, criminological commentary on the community approach to crime prevention has journeyed backwards and forwards, at times stressing the significance of informal social control on crime and disorder inside individual communities, while at other times orienting around the opportunity reduction model (or situational crime prevention) and emphasizing partnership/interagency working including community and problem-oriented policing. This research paper has analyzed the policy and practice of crime prevention and intervention in China, a process conforming to recognizable forms of community crime prevention in the West. However, its “Chinese characteristics,” resting upon unique forms of social capital, are also evident (Zhuo 2012). In addition, the state, through all the levels of the Chinese Communist Party, plays a determining role and it could hardly be otherwise. The state-led comprehensive approach both structures and mandates community organizations working with the police and other government agencies, in concerted efforts to achieve reductions in crime. As mentioned in the introduction, traditional strategies with new components underpin the approach: its ideological underpinnings and mass-line tradition reinvented by a responsibility system and incentivized by financial contract arrangements and government investment at all levels of governance make it distinctive from community crime prevention approaches described by Western commentators (Welsh and Hoshi 2002). Neighborhood committees still function as an important part of the grassroots organization but are under financial pressures and under challenge from newly emerging market influences and organizations. The public security bureaus (police) still uphold the mass line and place great emphasis on good relationships with the masses – yet actively try to adapt to the new environment of greater “police professionalization” and mixed markets in security provision. Dutton notes the irony of the revival of Maoist rhetoric and mass-line forms, since the “revival” actually signaled the demise of the significance of transformational politics; instead it was part of the slow process of political and ideological drainage that would change the nature of mass mobilization in China. The new dynamic fueling these developments has been monetary incentives rather than “revolutionary” volition (Dutton 2005: 260–262). The new money-incentivized forms are, in this sense, actually the commodification of mass-line security (Dutton 2005: 298–299).

Contracted services in private security vary appreciably across urban neighborhoods in China. For some newly established, affluent neighborhoods, private security companies provide a variety of services ranging from neighborhood cleaning to guarding services (Trevaskes 2007c). They engage in night patrol and manage security devices (CCTV cameras). Some of the services overlap with the activities traditionally performed by neighborhood police stations and residents’ committees. Furthermore, some neighborhoods, especially older ones, do not have any contracted services. Very little research has been conducted on the interconnections between the traditional organizational forms of prevention in neighborhoods (the comprehensive governance model) and contracted services.

Returning to the bifurcatory nature of China’s comprehensive approach, one should note that it is not without precedent. It has been argued that in the last three decades, the practice of crime prevention and intervention in both the UK and the USA exhibited two distinct patterns of action (Garland 2001): an adaptive strategy stressing prevention and partnership and a strategy aimed at identifying “dangerous” offenders and expressive punishment. The roots of such bifurcation lie in complex political rationalities – and China is not an exception to the playing out of such governmental processes (Liang 2005: 395). In the end, the nature and dynamics of change in China’s comprehensive crime prevention strategy can be understood as an anthem to how financial incentivization came to appear both normal and even natural, despite the fact of it being so alien to the planned economy of the past.

Finally, for those unfamiliar with the literature on policy and practice of crime prevention in the People’s Republic of China, this research paper has perhaps had a somewhat “strange” quality principally because there has been little comment on policy evaluation. Bowles et al. (2005) point to generic obstacles to evaluation of policy in developing countries, namely:

- A lack of empirical information about the functioning of institutions

- A lack of articulation of policy options and policy objectives

- A lack of articulation of the inputs, of the outputs and outcomes associated with interventions, and thus of the raw material for estimating the costs and benefits associated with interventions.

The lack of research-led evaluation in China merely confirms this litany of obstacles (Liang and Lu 2006).

Bibliography:

- Bakken B (2000) The exemplary society: human improvement, social control, and the dangers of modernity in china. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Bowles R, Akpokodje J, Tigere E (2005) Evidence-based approaches to crime prevention in developing countries. Eur J Crim Pol Res 11:347–377

- Chen X (2004) Social and legal control in China: a comparative perspective. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 48:523–536

- Chen Y-L (2012) A political and economic analysis of the strike hard policy. Develop Law Soc 104:87–95 (in Chinese)

- Dutton M (2005) Policing Chinese politics. Duke University Press, London

- Ekblom P, Pease K (1995) Evaluating crime prevention. In: Tonry M, Farrington D (eds) Building a safer society: strategic approaches to crime prevention. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Garland D (2001) The culture of control: crime and social order in contemporary society. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Hong D (2011) Research on changes to the mediation system in contemporary China. Shanghai People’s Press, Shanghai (in Chinese)

- Jiang B, Dai Y (1990) Mobilizing all possible social forces to strengthen public security – a must for crime control. Police Stud 13:1–9

- Liang B (2005) Severe strike campaign in transitional China. J Crim Just 33:387–399

- Liang B (2008) The changing Chinese legal system, 1978present. Routledge, New York/London.

- Liang B, Lu H (2006) Conducting fieldwork in China: observations on collecting primary data regarding crime, law, and the criminal justice system. J Cont Crim Just 22:157–172

- Liang B, Wilson C (2008) A critical review of past studies on China’s corrections and recidivism. Crim Law Soc Change 50:245–262

- Liu J (2005) Crime patterns during the market transition in China. Brit J Criminol 45:613–633

- Mao Z (1967/2010) Collected writings of Chairman Mao, volume 3 – on policy, practice and contradiction. El Paso Norte Press, San Francisco

- Muhlhahn K (2009) Criminal justice in China: a history. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Ren X (1997) Tradition of the law and law of the tradition. Greenwood, Westport

- Selden M (1971) The Yenan way in revolutionary China. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Situ Y, Liu W (1996a) Comprehensive treatment to social order: a Chinese approach against crime. Int J Comp Appl Crim Just 20:95–115

- Situ Y, Liu W (1996b) Restoring the neighborhood, fighting against crime: a case study in Guangzhou city, People’s republic of China. Int Crim Just Rev 6:89–102

- Trevaskes S (2007a) Swift and severe justice in China. Brit J Criminol 47:23–41

- Trevaskes S (2007b) Courts and criminal justice in China. Lexington Press, Lanham

- Trevaskes S (2007c) The public/private security nexus in China. Soc Justice 34:38–55

- Trevaskes S (2008) The war against organised crime and drug crime in china. Regional Outlook Paper No.15. Griffith Asia Institute, Brisbane, Australia

- Trevaskes S (2010) The shifting sands of punishment in the era of ‘harmonious society’. Law Policy 32:332–361

- Wang ZF (1989) (ed) Theory and practice of comprehensive management of public order in China. Masses Press, Beijing (in Chinese)

- Welsh B, Hoshi A (2002) Communities and crime prevention. In: Sherman L, Farrington DP, Welsh BC, MacKenzie DL (eds) Evidence-based crime prevention. Routledge, London

- Wilson AM, Greenblatt SL, Wilson RW (eds) (1977) Deviance and social control in Chinese society. Praeger, New York

- Yang YM (2010) Analyzing the fourth wave of the strike hard policy. Gov Leg Syst 36:22–23 (in Chinese)

- Zhang L, Messner SF, Liu J (2007a) A multilevel analysis of the risk of household burglary in the city of Tianjin, China. Brit J Criminol 47:918–937

- Zhang L, Messner S, Liu J (2007b) Criminological research in contemporary China: challenges and lessons learned from a large-scale criminal victimization survey. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 51:110–121

- Zhao J (2005) Conflicts between advantages and disadvantages in restorative justice. Law 5:113–115 (in Chinese)

- Zhao R, Liu J (2011) A system’s approach to crime prevention: the case of Macao. Asian J Criminol 6:207–227

- Zhong L (2008) Communities, crime and social capital in contemporary China. Willan, Cullompton

- Zhuo Y (2012) Social capital and satisfaction with crime control in urban China. Asian J Criminol 7:121–136

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.