This sample Lifestyle Theory of Crime Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Lifestyle theory holds that crime is a developmental process guided by an ongoing interaction between three variables (incentive, opportunity, and choice). During each phase of the criminal lifestyle (initiation, transition, maintenance, burnout/maturity), incentive, opportunity, and choice take on different values and meanings. Existential fear serves as the incentive for the initiation phase of a criminal lifestyle. Once initiated, the incentive for continued lifestyle involvement becomes a fear of losing out on the benefits of crime. By the time the individual enters the third (maintenance) phase of a criminal lifestyle, incentive has changed once again, this time to a fear of change. With the advent of the burnout/maturity phase of the criminal lifestyle, incentive has changed yet again, this time to a fear of death, disability, or incarceration. Comparable transformations take place in opportunity and choice. Current controversies include (1) generalizing results obtained from research on male prison inmates to that on female inmates and nonincarcerated offenders, (2) documenting the clinical predictive efficacy of assessment procedures designed to measure key lifestyle constructs, and (3) examining the possibility of an allegiance effect for much of the research on lifestyle theory. Open questions requiring further study include (1) investigating the hierarchical model of criminal thinking proposed by lifestyle theory, (2) exploring the role of criminal thinking and other quasi-time-stable cognitive factors in mediating and clarifying important crime relationships, and (3) ascertaining whether the lifestyle approach to intervention qualifies as evidence based.

Introduction

The lifestyle theory of crime has its roots in Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive model, Sykes and Matza’s (1957) techniques of neutralization, and Yochelson and Samenow’s (1976) work on the criminal personality. As such, it is designed to explain habitual criminal activity by focusing on the cognitive factors that support antisocial behavior. The cognitive-behavioral proclivities of lifestyle theory are obvious given its emphasis on cognition, behavior, and the cognitionbehavior relationship. Less obvious, perhaps, is how lifestyle theory integrates cognition and behavior. This research paper, in addition to describing the lifestyle theory of crime, is designed to provide the reader with an understanding of exactly how cognition and behavior interact to increase or decrease a person’s risk for future criminal involvement.

Background

For much of its history, criminology has restricted itself to a small portion of the relevant data, resulting in the simplistic single-variable theories that now dominate the field. Biology and psychology have been largely ignored by criminologists and while biology and psychology are no more capable of providing a complete explanation of crime than criminology, a complete explanation necessitates their inclusion. The lifestyle theory of crime attempts to highlight psychological variables that may be helpful in explaining certain well-known crime relationships. In this vein, lifestyle theory seeks to integrate constructs from divergent conceptual models rather than perpetuate the artificial dichotomies that seem to have limited theory development in the field of criminology (i.e., classicism vs. positivism, propensity vs. development, continuity vs. change). How lifestyle theory integrates these artificial dichotomies is discussed next.

Early criminological theory emphasized the classical perspective that humans are rationale decision makers who engage in behaviors they believe will provide them with the greatest amount of pleasure and the least amount of pain. The criminal justice system still relies heavily on the classical notion that people choose to commit crime. Theoretical criminology, however, has largely rejected the notion of choice in favor of a deterministic model of criminal behavior in which crime is seen as a function of sociological and environmental factors over which the actor has no control. Lifestyle theory integrates these opposing points of view into a single perspective in which incentive (pushes from within), opportunity (pulls from without), and choice (the decision-making apparatus) are equally important in the development of criminal behavior.

Some criminological theories view offenders as exhibiting a propensity for crime; other criminological theories postulate that crime follows a developmental sequence or pattern. The first approach underlies the career criminal paradigm and the second approach lays the foundation for the criminal career paradigm. Lifestyle theory asserts that crime is both a propensity and developmental process and that the career criminal and criminal career paradigms, rather than being diametrically opposed, are actually complementary. Integration of the career criminal and criminal career paradigms gives rise to four overlapping but sequential phases of lifestyle development: initiation, transition, maintenance, and burnout/ maturity. Certain propensities lead some individuals to drop out of the sequence during an early phase (initiation, transition) and others to avoid the sequence altogether. Alternate propensities lead some individuals to remain in the sequence or in a particular phase of the sequence longer than most people.

Continuity versus change is another dichotomy that has preoccupied the field of criminology. Some theorists conceptualize crime as a time-stable characteristic that is largely impervious to change, whereas other theorists conceptualize crime as an unstable developmental pattern that is subject to regular and dramatic periods of change. Crime continuity, whereby past offending serves as one of the best predictors of future offending across multiple studies, is often used to support the stability argument. The age-crime relationship, in which crime peaks during mid-adolescence and then drops off sharply in late adolescence regardless of whether crime is measured with official, self-report, or victimization data, is often used to support the instability argument. Lifestyle theory agrees with both positions and integrates stability and instability into its framework by proposing the existence of quasi-time-stable cognitive and behavioral variables that give the lifestyle the appearance of being both stable and changeable.

Another dichotomy that has helped shape the lifestyle theory of crime is whether individual differences in criminality are categorical (difference in kind) or dimensional (difference in degree). This time, however, one side of the controversy (i.e., dimensional latent structure) rather than an integration of the two sides receives the bulk of empirical research support. In a recent review of the taxometric literature on antisocial personality, psychopathy, and criminal lifestyle, Haslam (2011) concludes that these crime-related constructs are dimensional rather than categorical in nature and that individual differences in these crime-related psychological constructs are quantitative (people can be ordered along one or more dimensions) rather than qualitative (people can be grouped into types or categories). Based on taxometric and confirmatory factor analytic research (Walters 2009), lifestyle theory proposes that a criminal lifestyle is composed of two overlapping dimensions: proactive criminality and reactive criminality.

State Of The Art

The lifestyle theory of crime, as described in Walters (1990), has undergone several revisions and elaborations. This section on the state of the art of lifestyle theory provides a summary of the most recent version or iteration of lifestyle theory as applied to habitual criminal conduct (Walters 2012a).

Precursors To A Criminal Lifestyle

Prior to entering the initial phase of a criminal lifestyle, certain conditions are already in place. Two commonly observed precursors of a criminal lifestyle are templates and trial runs. A template consists of cultural and subcultural factors that provide a context for subsequent development of a criminal lifestyle. Sundry environmental and familial factors help shape an individual’s attitudes and thinking toward antisociality and crime, which, in turn, increase or decrease the person’s susceptibility to future criminogenic influences. The child’s interactions with the interpersonal environment consequently form a template that makes it more or less likely that he or she will pursue criminal opportunities present in that environment. Trial runs are the individual’s initial attempts to employ antisocial solutions to solve interpersonal problems (e.g., acquiring a toy they want, avoiding punishment for stealing a treat from the proverbial cookie jar). The reaction the child receives from his or her interpersonal environment will go a long way toward shaping his or her thinking with respect to future criminal opportunities.

Phase I: Initiation

The first phase of a criminal lifestyle is referred to as initiation. This phase begins with commission of the first arrestable crime and ends when the individual either adopts a conventional lifestyle or moves into the next phase of a criminal lifestyle. Each phase of a criminal lifestyle is a function of specific incentives, opportunities, and choices, around which the current discussion is organized.

Incentive: Existential Fear

Existential fear is a fear of nonbeing combined with a sense of separation and alienation from the environment. Although it is a fear shared by all humans, it is shaped and molded by a person’s experiences in the survival-relevant areas of affiliation, control/predictability, and status. Those whose fears have been shaped by affiliative concerns might experience existential fear as a fear of fitting in or being rejected. Those whose fears have been shaped by control concerns might experience existential fear as a fear of losing control. Those whose fears have been shaped by status concerns may perceive existential fear as a fear of being anonymous or unsuccessful. Existential fear serves as an incentive for behavior in that it motivates, pushes, or encourages the individual to engage in behaviors designed to reduce or alleviate the fear. The degree to which a criminal lifestyle promises the individual relief from existential fear is the degree to which the individual is motivated to enter a criminal lifestyle.

Initially, existential fear is tied to one’s physical survival. It is, in effect, a manifestation of the person’s survival instinct. This can become distorted over time, however, to where the individual paradoxically favors psychological survival of the lifestyle over physical survival of the organism. This is particularly true of a criminal lifestyle. Research indicates that criminality is often associated with low anxiety or fearlessness (Newman and Schmitt 1998). Lifestyle theory conceptualizes fearlessness as a relatively weak bond between existential fear and physical survival, keeping in mind that lifestyle theory is a dimensional model and that bond strength is a matter of degree rather than an all-ornothing proposition. Because existential fear needs to be attached to something, the individual with low fearlessness will often attach their existential fear to a lifestyle. Under the proper conditions, this lifestyle could turn out to be a criminal lifestyle.

Opportunity: Early Risk Factors

Opportunity factors increase or decrease a person’s risk of entering a lifestyle. In line with the criminal lifestyle’s dimensional structure, no single risk factor determines a person’s position on the proactive and reactive dimensions of the lifestyle; rather, it is the total number of relevant risk factors that is important (additive etiology). Some risk factors have a greater impact than other risk factors, certain risk factors interact with one another, and some risk effects are moderated by a third variable. Childhood temperament is considered a particularly salient risk factor for the purpose of initiating a criminal lifestyle. Novelty seeking, negative emotionality, and physical activity are three temperament dimensions likely to be elevated in someone at risk for future antisociality. Because childhood temperament is a function of both genetics and early environment, it demonstrates the complex interaction that exists between biological and developmental factors in the formation of a criminal lifestyle. Other risk (opportunity) factors vital during the initiation phase of a criminal lifestyle include stress, weak socialization to conventional groups, strong socialization to deviant groups, and the availability of criminal opportunities in the current environment.

Choice

Lifestyle theory rejects the hard determinism of the positivistic tradition. Even though incentive drives behavior and opportunity shapes it further, the individual still makes choices. The active decision-making that gives rise to choice is a two-stage process: generation and evaluation. The goal of the generation stage of the decisionmaking process is to come up with as many alternative solutions to a problem as possible. The goal of the evaluation stage of the decisionmaking process is to systematically and effectively evaluate the pros and cons of each alternative option. For a variety of reasons, from intelligence to experience to poor integration of decisional economics (rational choice) and emotion (empathy), the crime-prone individual often has trouble generating alternatives, properly evaluating alternatives, or both. This is a problem during all four phases of a criminal lifestyle, but during the initiation phase the issue often is resisting the powerful effects of actual and anticipated positive reinforcement for criminality (excitement, curiosity, peer acceptance). Lifestyle theory rejects traditional rational choice and deterrence theory in favor of a model that encompasses both rational and irrational choice.

Phase II: Transition

The transitional phase of lifestyle development is characterized by increased involvement in, commitment to, and identification with the criminal lifestyle. In contrast to the experimentation of the initiation phase, the transitional phase is marked by a growing sense of comfort with the lifestyle accompanied by the belief that certain basic needs will be satisfied by the lifestyle.

Incentive: Fear Of Lost Benefits

It is during the initiation phase of a criminal lifestyle that the individual comes to realize the material and psychological benefits that can be derived from being involved in a regular pattern of criminality. Existential fear facilitates the transition to a higher level of lifestyle involvement by stimulating a person’s fear of losing the material (money, excitement, power) and psychological (affiliation, control, status) benefits of a criminal lifestyle. This transformation of existential fear into a fear of losing the material and psychological profits of a criminal lifestyle is instrumental in transitioning the individual to the next phase of the lifestyle whereby commitment to the lifestyle and certain corollaries (initial incarceration, labeling, rejection of conventional values) take precedence.

Opportunity: Schematic Subnetworks

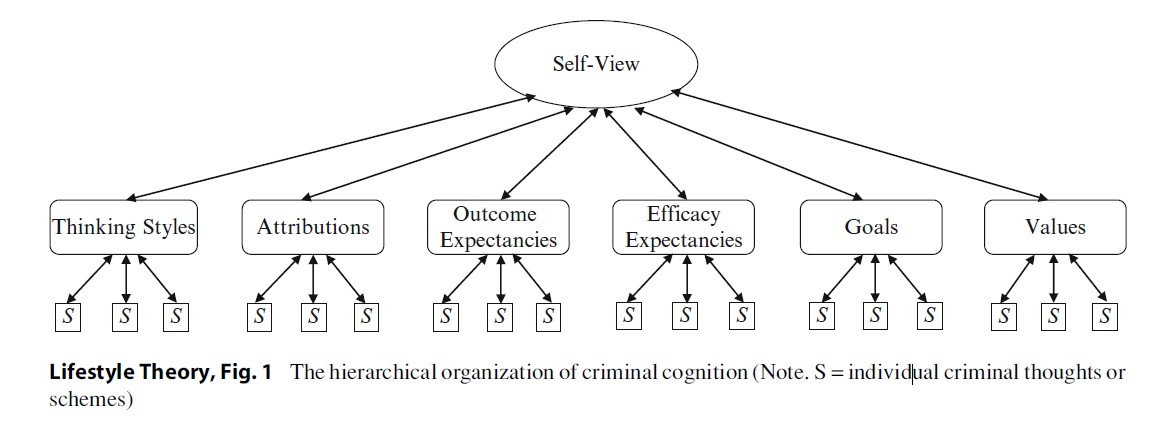

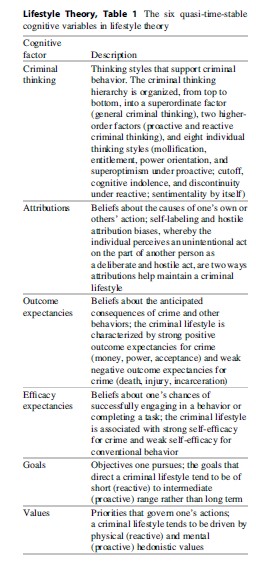

With increased internalization of the criminal lifestyle, opportunity transitions from behavioral to cognitive. This is another way of saying that a person starts acting like a criminal before he or she starts thinking like one. Once the individual starts thinking like a criminal, his or her opportunities are shaped primarily by six cognitive factors known as schematic subnetworks. Lifestyle theory proposes that criminal cognition is hierarchically organized; with belief systems (selfview, worldview, past view, present view, future view) at the top of the hierarchy, individual criminal thoughts are the bottom of the hierarchy, and several layers of schematic subnetwork in between (see Fig. 1). The six primary schematic subnetworks in the lifestyle model are thinking styles, attributions, outcome expectancies, efficacy expectancies, goals, and values (see Table 1 for more details).

Choice

Decision-making tends to narrow as the individual’s commitment to a criminal lifestyle grows. Many people who enter the transitional phase of a criminal lifestyle never possessed good problem-solving skills to begin with. Of those who enter this phase with adequate problemsolving skills, it is the generation stage of the problem-solving process that is most adversely affected by the individual’s growing commitment to a criminal lifestyle. As the person begins narrowing the focus of his or her problem-solving deliberations to criminal options, he or she starts a process, facilitated, in part, by criminal thought patterns and other schematic subnetworks (which can be considered purveyors of irrational choice), of discarding and denigrating the noncriminal options available to him or her. Near the end of the transition phase, it is not uncommon to find the proactive (scheming, cold-blooded, e.g., “what’s in it for me?”) and reactive (impulsive, hot-blooded, e.g., “I’ll get you for that!”) dimensions of decision-making exerting independent, simultaneous, and poorly modulated effects on behavior.

Phase III: Maintenance

Whereas the majority of those who enter the initiation phase of a criminal lifestyle never progress to the transitional phase and a sizeable minority of persons who move into the transitional phase drop out before entering the maintenance phase, there is virtually no attrition from the maintenance phase. This is because the maintenance phase of a criminal lifestyle is a period of maximum lifestyle involvement, commitment, and identification.

Incentive: Fear Of Change

As scary as a criminal lifestyle and its consequences (injury, death, and incarceration) may be, they are often not as frightening as the prospect of change. Fear of change consequently becomes the primary incentive for remaining in a criminal lifestyle long after it has stopped being fun. The individual feels compelled to remain in

Outcome expectancies

Beliefs about the anticipated consequences of crime and other behaviors; the criminal lifestyle is characterized by strong positive outcome expectancies for crime (money, power, acceptance) and weak negative outcome expectancies for the lifestyle even though the benefits no longer seem to outweigh the costs, and it is a fear of change or better yet, a fear of the unknown, that is behind the individual’s inactivity and apparent immobility. Things may not be as the person would like them to be but there is comfort to be found in the familiar, even when the familiar is no longer as comfortable as it once was. Giving up crime may be interpreted as symbolic death by someone in the maintenance phase or at least tacit acceptance that the years spent in a lifestyle were a waste of time and a poor decision on his or her part.

Opportunity: Psychological Inertia

Psychological inertia is based on Newton’s first law of motion, which states that a body at rest will remain at rest and a body in motion will remain in motion unless acted upon by an outside force. Once a criminal lifestyle is in motion, it will maintain itself until acted upon by an outside force for change. The progenitors of psychological inertia are the six schematic sub-networks mentioned in the previous section on transition. Each of these quasi-time-stable cognitive factors gives rise to continuity in criminal behavior. Criminal thinking, for instance, provides offenders with a way of understanding the world that is consistent from one situation to the next and helps rationale their ongoing criminal behavior. Attributions like self-labeling, outcome expectancies of unlimited power and control, high self-efficacy for crime and low self-efficacy for conventional behavior, short-term goals, and hedonistic values all keep the individual locked in chronic pattern of offending by way of psychological inertia.

Choice

During the maintenance phase of a criminal lifestyle, the individual may truly believe that he or she has no choice other than to remain in the lifestyle. Given that lifestyle commitment is maximal during this phase, it is easy to see why many late phase offenders feel “stuck” in the lifestyle or view continued criminal involvement as their “fate.” Hence, attitudes expressed by probation officers, correctional staff, or even counselors suggesting that offenders never change (i.e., “once a criminal, always a criminal”) may serve to inhibit the natural changes process that leads to change in even the most recidivistic of offenders. The ability to generate and evaluate alternatives is almost universally weak in those who reach the maintenance phase of a criminal lifestyle. Fear of change and psychological inertia only serve to reinforce the fatalistic belief that their situation will never change. There is hope, however, and this hope arrives in the form of the fourth and final phase of a criminal lifestyle, burnout and maturity.

Phase IV: Burnout And Maturity

The combined effect of the negative long-term consequences of a life of crime and the aging process leads to the fourth and final phase of a criminal lifestyle, burnout and maturity. Whereas burnout is a decrease in physical energy and stamina that makes crime more difficult and less pleasurable, maturity is a psychological process involving a genuine change in interests, goals, values, and activities. Physical burnout is inevitable, psychological maturity is not. An individual who is physically burned out but has not yet achieved psychological maturity may switch to a less physically taxing criminal activity, like dealing in stolen property; nevertheless, he or she will remain on the outskirts of the lifestyle. Whereas the transition from the maintenance phase of a criminal lifestyle to burnout and maturity can be abrupt, it is normally a gradual and uneven process.

Incentive: Fear Of Death, Disability, And Incarceration

With respect to fear, the offender has come full circle once he or she enters the burnout/maturity phase of a criminal lifestyle. One of the factors associated with initiation of the lifestyle is a weakened bond between existential fear and physical survival and the creation of a robust bond between existential fear and some activity, in this case, the criminal lifestyle. During burnout/maturity the bond between existential fear and physical survival strengthens, while the existential fear-lifestyle bond weakens. This is achieved by way of a growing fear of incarceration, a fear of dying in prison, and fears associated with the negative consequences of a criminal lifestyle, namely, death, injury, and disability.

Opportunity: Approach And Avoidance

Several factors support desistence from crime by increasing opportunities for prosocial activity and decreasing opportunities for antisocial activity. This can be accomplished by approaching goals, options, and outcomes incompatible with crime, such as marriage, parenthood, and conventional employment, or avoiding goals, options, and outcomes compatible with crime, such as drug use, criminal associates, and settings where one has committed crime in the past. As approach and avoidance opportunity factors interact, burnout and maturity increase and the risk of future criminal involvement drops dramatically.

Choice

Choice plays a vital role in crime initiation, maintenance, and desistance. During burnout and maturity, its role is to focus the individual on the rapidly accumulating negative consequences of criminal behavior, from incarceration to death. Many individuals, as they get older, become better problem solvers. Age seems to have a positive effect on a person’s ability to both generate and evaluate alternatives and the negative consequences that accompany a criminal lifestyle are more difficult to accept and tolerate as the person ages. More people exit a criminal lifestyle during the initiation phase, but the greatest proportion of people exit the lifestyle during burnout and maturity. Fear of death, disability, and incarceration; approaching prosocial situations and avoiding antisocial ones; and placing greater emphasis on the negative consequences of crime than on the perceived benefits of crime are at the heart of the burnout and maturity phase.

Current Controversies

Nearly all of the research on lifestyle theory has been conducted on male inmates serving time in US federal prisons. A handful of studies have been conducted on US state prisoners and forensic patients and several studies have been done on European samples but only one study used female participants (Walters et al. 1998), and no studies have tested lifestyle theory in community corrections clients. The research base for lifestyle theory must consequently be expanded. Not only is there a need for more research on female offenders and community samples, but research on the invariance of lifestyle principles across ethnic groups and crime categories is also required. Research on juvenile samples is also needed. Whereas application of lifestyle theory to children and adolescents has been covered recently (i.e., Walters 2012a), there have been no research studies on lifestyle theory in which juveniles have served as subjects.

Assessment procedures have been developed to measure key concepts in lifestyle theory but the clinical utility of these measures remains largely untested. Thus far, the Lifestyle Criminality Screening Form (LCSF: Walters et al. 1991) has been developed to assess the behavioral dimensions of a criminal lifestyle (irresponsibility, self-indulgence, interpersonal intrusiveness, and social rule breaking), the Psychological Inventory of Criminal Thinking Styles (PICTS: Walters 1995) can be used to assess criminal thinking, and the Outcome Expectancies for Crime scales (OEC: Walters 2003) are available for assessing positive and negative outcome expectancies for crime. In the name of clinical utility, these measures should be capable of predicting important crime outcomes like recidivism with at least modest to moderate effectiveness. In addition, they should also possess incremental validity relative to easily obtained measures like age and criminal history.

Meta-analyses have been conducted on the LCSF (k = 11) and PICTS (k = 7) as predictors of recidivism, with r serving as the effect size measure and studies being combined using the random effects model. The results reveal a weighted effect size of .23 (95 % CI = .15–31) for the LCSF and .20 (95 % CI = .15–24) for the PICTS General Criminal Thinking (GCT) score. Viewing these results relative to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines for small (.10), moderate (.24), and large (.37) effect sizes, we can see that the LCSF and PICTS both achieved effect sizes in the small to moderate range. Because the LCSF is a measure of criminal history, it is not possible to evaluate its ability to predict recidivism beyond the effects of age and criminal history. However, when the PICTS GCT score was entered into a regression equation behind age and criminal history, it continued to predict recidivism above and beyond the contributions of age and criminal history (Walters 2012b). A meta-analysis or incremental validity analysis could not be performed on the OEC because of a lack of recidivism data.

Theoretical articles and research reports on lifestyle theory have been published largely by one individual, the author of lifestyle theory. An allegiance effect can arise any time an author is evaluating his or her own theory and is most commonly observed in studies where an assessment device or therapeutic modality is being evaluated. Eight of the eleven LCSF studies and five of the seven PICTS studies included in the previously mentioned meta-analyses were performed by the author of lifestyle theory (Walters). A small difference was observed when the 13 effect sizes obtained in studies by Walters (r = 0.23, 95 % CI = 0.17–0.28) were compared with the five effect sizes obtained in studies conducted by outside researchers (r = 0.18, 95 % CI = 0.09–0.26); however, the difference disappeared when a single outlying study was removed from the outside researcher group (r = 0.22, 95 % CI = 0.14–0.29). Only two empirical studies have evaluated the lifestyle approach to intervention and both were published by Walters (1999; 2005). Until outside researchers conduct more studies on lifestyle theory, the possibility of an allegiance effect for research on lifestyle theory remains an open question.

Open Questions

Besides investigating whether an allegiance effect accounts for some of the positive results obtained in research on lifestyle theory, there are three other open questions that demand attention. First, there is a need for more research on the hierarchical structure of criminal thinking. This hierarchy fits into the criminal thinking schematic sub network box found in Fig. 1, with general criminal thinking at the top, proactive and reactive criminal thinking in the middle, and the eight individual criminal thinking styles at the bottom. Applying item response theory (IRT) principles and confirmatory factor analysis to a sample of nearly 3,000 incarcerated male offenders, Walters, Hagman, and Cohn (2011) determined that the sentimentality scale did not load onto either of the two higher-order factors (proactive, reactive) or the superordinate general criminal thinking factor. Based on these results, it has been recommended that instead of calculating the GCT score by combining the raw scores of the eight thinking style scales, the seven thinking style scales other than sentimentality be used to calculate the GCT. Further research is nonetheless required to cross-validate these results in a noninstitutionalized sample.

A second open question is whether the cognitive factors in lifestyle theory mediate important crime relationships. In the first of several studies, Walters (2011) discovered that the PICTS GCT score partially mediated the relationship between a history of serious mental health problems and subsequent institutional violence in a group of federal prison inmates. A second study found that the GCT score partially mediated the relationship between race and recidivism (Walters in press b) and a third study revealed that the PICTS Reactive Criminal Thinking score partially mediated the relationship between prior substance abuse and subsequent recidivism (Walters 2012c). In a fourth study, Walters (in press a) determined that the GCT score and weak self-efficacy to avoid future police contact both mediated the relationship between past and future criminal conduct. It would appear that at least some of the quasi-time-stable cognitive factors in lifestyle theory are capable of mediating crime-relevant relationships, although further research is required to ascertain the extent to which the effect applies to all six factors. A third open question is whether lifestyle intervention can be considered evidence based. Given that there have been only two empirical studies on lifestyle intervention to date (Walters 1999; 2005), there is insufficient evidence at this time to conclude that lifestyle intervention is evidence based. Nevertheless, the approach is manualized and has been adapted for use in an outpatient substance abuse program in Denmark (Thylstrup and Morten Hesse in press). One of the founding principles of lifestyle intervention is that while behavior proceeds cognition in the development of a lifestyle (i.e., a person starts acting like a criminal before he or she starts thinking like one), cognition proceeds behavior in lifestyle change (i.e., a person stops thinking like a criminal before he or she stops acting like one). Although cognition and behavior cannot be meaningfully separated, the early stages of lifestyle intervention focus primarily on challenging criminal thinking patterns and other cognitive mediators of criminal behavior, with the behavioral interventions becoming more prominent at latter stages of the treatment process. Research is required, however, to determine whether the progression proposed by lifestyle theory (i.e., start by focusing on cognition and then move into behavior) is justified.

Conclusion

The lifestyle theory of crime is presented for the purpose of illustrating how psychological factors are capable of furthering our understanding of criminal behavior. Lifestyle theory seeks to reconcile popular dichotomies in the field of criminology (classicism vs. positivism, propensity vs. development, continuity vs. change) by incorporating features of criminality that have been largely ignored by traditional criminological theories. After reviewing the developmental progression vital in initiating and maintaining a criminal lifestyle, controversial topics and open questions concerning the theory are discussed. The future of lifestyle theory depends on its ability to attract the attention of outside researchers and clinicians so that the model’s potential can be tested and its limitations delineated.

Bibliography:

- Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

- Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale

- Haslam N (2011) The latent structure of personality and psychopathology: a review of trends in taxometric research. Sci Rev Mental Health Prac 8:17–29

- Newman JP, Schmitt WA (1998) Passive avoidance in psychopathic offenders: a replication and extension. J Abnorm Psychol 107:527–532

- Sykes GM, Matza D (1957) Techniques of neutralization: a theory of delinquency. Am Sociol Rev 22:664–670

- Thylstrup B, Hesse M (in press) The impulsive lifestyle counseling program for antisocial behavior in outpatient substance abuse treatment. Int J Offender Therapy Comp Criminol

- Walters GD (1990) The criminal lifestyle: patterns of serious criminal conduct. Sage, Newbury Park

- Walters GD (1995) The psychological inventory of criminal thinking styles: part I. Reliability and preliminary validity. Crim Justice Behav 22:307–325

- Walters GD (1999) Short-term outcome of inmates participating in the lifestyle change program. Crim J Behav 26:322–337

- Walters GD (2003) Changes in outcome expectancies and criminal thinking following a brief course of psychoeducation. Personal Individ Differ 35:691–701

- Walters GD (2005) Recidivism in released lifestyle change program participants. Crim Justice Behav 32:50–68

- Walters GD (2009) Latent structure of a two-dimensional model of antisocial personality disorder: construct validation and taxometric analysis. J Personal Disord 23:647–660

- Walters GD (2011) Criminal thinking as a mediator of the mental illness-prison violence relationship: a path analytic study and causal mediation analysis. Psychol Serv 8:189–199

- Walters GD (2012a) Crime in a psychological context: from career criminals to criminal careers. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Walters GD (2012b) Criminal thinking and recidivism: meta-analytic evidence on the predictive and incremental validity of the psychological inventory of criminal thinking styles (PICTS). Aggress Violent Behav 17:272–278

- Walters GD (2012c) Substance abuse and criminal thinking: testing the countervailing, mediation, and specificity hypotheses. Law Human Behav 36:506–512

- Walters GD (in press a) Cognitive mediation of crime continuity: a causal mediation analysis of the past crime-future crime relationship. Crime Delinq

- Walters GD (in press b) Relationships between race, education, criminal thinking, and recidivism: moderator and mediator effects. Assessment

- Walters GD, Elliott WN, Miscoll D (1998) Use of the psychological inventory of criminal thinking styles in a group of female offenders. Crim Justice Behav 25:125–134

- Walters GD, Hagman BT, Cohn AM (2011) Toward a hierarchical model of criminal thinking: evidence from item response theory and confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Assess 23:925–936

- Walters GD, White TW, Denney D (1991) The lifestyle criminality screening form: preliminary data. Crim Justice Behav 18:406–418

- Yochelson S, Samenow SE (1976) The criminal personality: vol. 1. A profile for change. Aronson, New York

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.