This sample Measuring Police Unit Performance Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Although police performance measurement has gotten increased attention in recent decades (Shane 2007; Fleming and Scott 2008; Davis 2012), it has been a longstanding concern of scholars and policy makers (Lind and Lipsky 1971; Parks 1971). The ability to measure how well the police are performing is central to notions of police effectiveness, accountability, reform, and the current emphasis on evidence-based policing. Without accurate performance measurement, aspirations toward implementation of strategic policing, scientific policing, and a new approach to police professionalism (Weisburd and Neyroud 2011; Stone and Travis 2011) are mostly rhetoric, not reality.

In the United States, where most police agencies are extremely small (one-half have ten or fewer police officers; Reaves 2011), the majority of the focus has been on the overall performance of the entire police organization, rather than on police unit performance (Langworthy 1999). Even in the United States, however, many police organizations are comprised of multiple subunits; this is the normal characteristic of police organizations in most of the rest of the world. These subunits are important to consider, because the overall performance of a medium-sized or large police agency is, at least to a degree, the sum of the performance of its parts. Top-level police executives have the challenge of measuring the performance of their organizations’ subunits in order to guide resource allocation, hold lower-level managers accountable, fix problems, and coordinate interunit activity. Lower-level police managers, especially if they are responsible for specific subunits, need information about how well their own units are performing in order to carry out their responsibilities of planning, directing, and controlling in order to maximize their units’ performance.

Fundamental Considerations

Conceptualizing and operationalizing “performance” is not as easy as it sounds. Commonly, a distinction is made between effort, output, and outcome. For example, the performance of a manufacturing unit within a larger company might be defined in three different ways:

- How hard did the members of the unit work?

- How many widgets did the unit produce?

- How much profit was derived from the unit’s performance?

Each of these measures of performance is legitimate and might be relevant. The company’s top management probably wants to be assured that the members of the manufacturing unit are working hard. If not, the unit might be overstaffed and therefore costing more than necessary. Second, top management certainly wants to know the level of production (output) of the unit, particularly in the case of a manufacturing unit, since that is its fundamental purpose (produce widgets). Ultimately (third), top management wants to know the unit’s contribution to the company’s profit. That is arguably the most important dimension of the unit’s performance, since it directly coincides with the entire company’s bottom line (its profit). After all, if the company is not profitable, it will go out of business, and then there will not be a manufacturing unit or any jobs for the members of the unit.

Several significant complications arise even from this simple example. With regard to effort, members of a unit might work hard, but make many mistakes. They might work hard, but be doing the wrong things. They might work hard, but not have the proper equipment needed to complete their work correctly. Also, if the unit’s role is more analytical, intellectual, or creative than this manufacturing example implies, then “working hard” might not be the primary ingredient of the effort associated with good performance. Rather, wise decision making, innovative problem solving, imaginative thinking, or just “working smart” might be better ways than “working hard” of conceptualizing the effort dimension of performance as it relates to some organizational units.

With regard to output, an organizational unit might produce a satisfactory number of widgets but the quality of the widgets might not be acceptable. Similarly, the number of widgets produced might be adequate but the amount of resources consumed in producing them could be excessive – i.e., there might be wastage of raw materials, driving up the cost of producing the widgets. As these two scenarios suggest, the output of a unit cannot be assessed in a meaningful way without incorporating some standard of quality as well as a measure of cost.

In principle, a unit’s outcomes are even more important than either its effort or its output, since the outcomes are the end results of the unit’s performance. This is particularly true when the outcomes are closely associated with the entire organization’s “bottom line,” such as its profit. Two related complications arise at this level, however. First, simply determining the end results of a unit’s performance can often be difficult. A company’s training unit, for example, might have as its desired end results increased employee knowledge, increased employee skills, and improved employee performance. The first two could be measured immediately after the conclusion of training programs. This would give some indication of training outcomes, but subsequent measurements would have to be made to determine whether the employees’ knowledge and skills were maintained over time. It would be even more involved (and costly) to measure employee performance back on the job, in order to see whether there was any post-training improvement in actual performance. The greatest challenge would be in “proving” that the training unit’s efforts either did, or did not, cause any changes in employee performance. Changes in performance could be caused by other factors – pay, supervision, new technology, etc. Or, measurement of employee performance might indicate no improvement following training – but that might be caused by workgroup pressures (e.g., output limitation norms), failure of supervisors to reinforce training, or many other factors, not necessarily some shortcoming of the training. In other words, validly determining whether a unit’s efforts did or did not cause some specified end results (outcomes) sometimes requires a genuine research project, not simply collecting some information.

These challenges are multiplied when one seeks to determine the contribution of a unit’s performance to the entire organization’s achievement of its specified outcomes. Again, this is what matters the most, but it is difficult to determine. The manufacturing unit may have produced perfectly good widgets at a satisfactory cost, but if the marketing unit failed to market them effectively, or if the sales unit failed to sell them, or if the packaging unit failed to design and produce the right packaging for them, or if the public’s taste in widgets changed, the widgets might still be in the warehouse nine months later, not contributing to the company’s profit. Would it be fair then to assess the manufacturing unit’s performance negatively? This scenario illustrates the fact that one unit’s contribution to the overall organization’s performance may be heavily dependent on the performance of other units.

A second major challenge arises when a unit’s contribution to overall organizational outcomes is indirect or tangential, as in the example of the training unit. In principle, the ultimate value of the training unit is tied to its contribution to the organization’s overall performance and effectiveness. If there was no connection, the training unit should not exist. However, most of what the training unit does is provide knowledge and skills to employees. Whether the employees actually use that knowledge and skill, whether they use it correctly, whether they are allowed to use it by co-workers and supervisors, whether they have the equipment they need, and many other factors are far beyond the control of the training unit. Equally important, the employees’ performance might improve due to training, but the impact of this improvement on overall organizational performance may not be detectable amidst all the other dynamic conditions, both inside and outside the organization, which are constantly in flux. For organizational units, such as training, that are somewhat distant from core operating functions, assessment based on contribution to the organization’s overall bottom line may be impractical or impossible.

In addition to all these complications, it should be noted that there is a tendency toward suboptimization in organizations. This refers to the tendency of organizational subunits to emphasize accomplishment of their units’ objectives (outputs or outcomes) even when those conflict with overall organizational goals and effectiveness. If the manufacturing unit is judged on the number of widgets produced, it may maximize that production, regardless of whether they are selling. Or, if it is judged on the percentage of widgets produced that meet a high standard of quality, it may slow production in order to take more time in making each widget, regardless of whether the sales unit then loses customers because the rate of delivery is too slow. This happens, of course, in part because members of a unit come to identify with it, often more closely than they identify with the entire organization. Also, if a unit is judged on a specific criterion of effort, output, or outcome, its members and its manager will often focus their entire energy on meeting that criterion, to the exclusion of other criteria that may be important, and without regard to how it may affect other units or the organization as a whole. This is a reflection of the common refrain, “what get’s measured gets done.” Sometimes, what does not get measured, does not get done.

Measuring Police Performance

All of the general considerations noted above apply to police organizations. Unit performance is sometimes measured based on effort, such as vehicles stopped, miles driven, average response time to reported incidents, properties checked, number of vehicle crashes reconstructed, and number of K-9 unit responses. It is particularly common to measure police unit performance in terms of outputs – number of reports taken, quantity of drugs seized, number of citations issued, number of arrests, proportion of cases cleared, etc. It is substantially less common to assess police organizational units based on outcomes. This is not surprising since the same is generally true regarding overall police organizational performance – police agencies have traditionally resisted being held accountable for the level of crime in their jurisdiction, and few if any other outcome measures were even considered. Until fairly recently, overall police organizational performance has generally been measured using response time, arrests, citations, and case clearances – measures that mainly address effort and outputs, not outcomes.

A few key characteristics of the police mission make performance measurement particularly complex. One is that a police organization’s “bottom line” is multidimensional. In the simple example given above, the widget company’s bottom line was unidimensional – profit. The company could easily and accurately tell how well it was doing, and, within the constraints discussed above, determine how well or poorly the manufacturing unit was contributing to the bottom line. Compare that to a police department that has a hypothetical three-part bottom line: reduce crime, maintain order, and protect constitutional rights. Right away, it is more difficult for the police department to know how well it is doing, because it must monitor three separate indicators, each of which may be quite hard to measure. In addition, working toward accomplishing any one of the three criteria may lead to some neglect of the others, since time and resources are always limited. Moreover, pushing hard on one may actually conflict with accomplishment of another. What is created is a tricky balancing act built on a foundation of uncertainty, since data on each of these conditions are liable to be incomplete at best.

Another important factor is that “how the police behave” (process) is of equal importance to “what the police accomplish” (outcome). For the most part, this is not true of the fictional widget company and its manufacturing unit. The company CEO could say to the head of the manufacturing unit, “I want you to produce 1,000 widgets a day and I do not care how you do it.” Certainly, there would be cost considerations, but the method by which the unit produced the widgets could be left entirely to the discretion of the manufacturing unit head. The same cannot be said in police organizations (Sunshine and Tyler 2003; Cordner 1978). A police chief might say to a police tactical unit commander, “I want you to reduce crime by 10 %,” but the unspoken remainder of the message would be that it would have to be done within the budget, within the law, without interfering with the accomplishment of other important outcomes, and without upsetting the community. And it would have to look good in the next day’s newspaper (or that night’s blogs). The point is not simply that police organizations operate under constraints, but also that police organizations are judged as much on how they behave (their actions, efforts, and outputs) as they are on outcomes (what they accomplish). To put it another way, even though, in principle, we should want to assess organizations (and their units) as much as possible in relation to outcomes, in the case of police organizations (and their units), there are valid reasons to measure what they do in addition to what they accomplish.

Because of the nature of the police mission, it may also be important to measure performance outcomes that are not immediately obvious. To give an exaggerated example, a desired outcome might be reduction of traffic accidents and fatalities. A police organization might achieve this outcome by reducing all speed limits to 5 miles per hour and writing citations to every driver who went any faster. Merely on the basis of the specified outcome, it would seem that the organization’s performance could be judged exemplary. However, there would probably be other outcomes of this brand of police performance, including greatly inhibited traffic flow, commercial trucking losses, irate drivers, and reduced police performance in relation to other outcomes, since officers would be totally consumed with traffic enforcement. The point is that measurement of police performance may sometimes need to take account of the side effects, negative effects, and unintended consequences of performance. Otherwise, false conclusions might be drawn about the effectiveness of the performance.

A useful framework for police performance measurement that incorporates a multidimensional bottom line and that also includes process and outcome dimensions was developed by Moore and Braga (2003). The framework identifies seven categories of performance that can be used to assess a police organization’s overall effectiveness, as noted below. A nice feature is that the seven categories also cover some of the most likely side effects and unintended consequences of police activity, such as abuse of authority, decreased legitimacy in the eyes of the public, and excessive cost. The first four categories reflect mainly outcomes, the fifth combines outcome and output, and the last two refer to processes. These same categories can be used in assessing the performance of individual police units, particularly to determine whether they contribute to overall organizational effectiveness, recognizing that all seven dimensions may not be directly applicable to every separate unit within the organization.

- Reduce crime and victimization

- Call offenders to account

- Reduce fear and enhance personal security

- Ensure civility in public spaces (ordered liberty)

- Quality services/customer satisfaction

- Use force and authority fairly, efficiently, and effectively

- Use financial resources fairly, efficiently, and effectively

Police Unit Performance

Based on the preceding discussions, it makes the most sense to measure police unit performance in two ways: (1) measures of effort, output, and outcome directly tied to the unit’s specific responsibilities, and (2) measures of the unit’s performance in relation to the seven performance categories noted just above. The first set of measures is likely to be the most specific and tangible, while the second set is ultimately the most important. In other words, the number of citations issued might be a clear indication of how hard the traffic unit is (or is not) working, but what ultimately matters the most is the number of traffic crashes and fatalities (as long as the means of reducing crashes is not too draconian, as per the earlier example), an element of “ensure civility in public spaces.”

Measurement of police performance in three different types of police units is discussed below: a police district or precinct, a specialized operational unit, and a support unit. These three types of units represent the vast majority of units likely to be found in police organizations.

Police District Or Precinct

Large police organizations are usually divided into districts or precincts, which are geographically based units responsible for providing a variety of police services. Districts or precincts almost always provide patrol services – preventive patrol, response to calls, community policing, and problem solving. Whether they are also responsible for other operational functions such as investigations and traffic enforcement varies. Some police organizations decentralize one or more specialized functions to the district/precinct level, while others centralize everything other than patrol at the headquarters level.

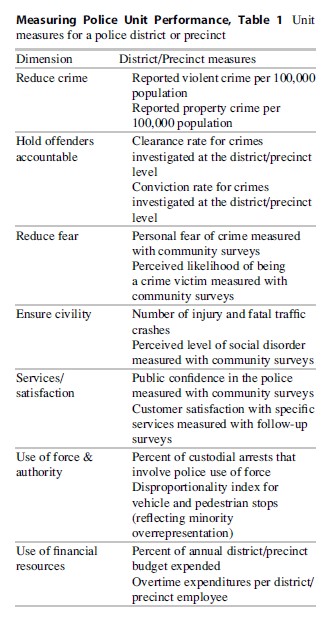

Compared to other police units, the responsibilities of a district or precinct are broad, and therefore, a variety of measures are likely to be needed to measure performance. In fact, all seven of Moore and Braga’s dimensions of police performance might be applicable. In order to assess the performance of a police district/precinct, a top police executive might want data for the following measures:

A positive feature of using this measurement approach is that it employs a breadth of measures to match the breadth of functions performed by the district/precinct unit. Also, the measures are mainly associated with outcomes, which arguably is both preferable and reasonable when focusing on a core operational unit – the district/ precinct has the opportunity to reduce crime, solve crimes, make the public feel safer, and so forth, in contrast to support units that can only hope to accomplish these kinds of outcomes indirectly. Of course, the two specific measures listed for each performance dimension can certainly be debated and better measures might be identified.

One disadvantage of this measurement scheme is complexity. Fourteen measures are quite a few, and it could be argued that the tendency would be to divide the district/precinct’s attention across too many indicators, resulting in scattered rather than focused performance. This is similar to the observation that too many objectives are almost worse than none. In response, though, it must be argued that multiple indicators are necessary when functions are so broad. It then becomes the manager’s responsibility to set priorities and identify areas of performance in need of greater emphasis, based on the performance data.

This multi-measure approach contrasts sharply with Compstat, which has become the most popular method for measuring the performance of police districts/precincts, and for using performance measurement to hold commanders accountable (Henry 2002). Compstat systems typically rely on just one measure, reported crime, perhaps supplemented with information about arrests and crimes solved. Pressure is put on district/precinct commanders to reduce reported crime and to show arrests in response to any crime increases that occur. While this system has the virtue of focusing everyone’s attention on the one measure that probably does deserve the highest priority, it typically fails miserably in taking into account the full range of the police mission in a geographic area, and thus, its one measure grossly misrepresents the full performance picture. Also, the extreme emphasis on one measure creates temptations on the part of unit managers to manipulate the data in order to look better on that measure (Eterno and Silverman 2012).

Another feature of the seven-dimension, fourteen-measure framework presented above is that it does not incorporate much information on effort or outputs. It does not measure miles driven, number of arrests, or response time (or at least it does not present them as measures of unit performance). A three-part explanation can be offered. First, these measures of effort and output may simply not matter in and of themselves, but only in relation to the accomplishment of larger outcomes. A police chief probably does not care whether the public in a district is reassured by the sight of many police cars driving about, or by the sight of police officers walking about, or by the sight of police officers in the mall when they go shopping, or by their knowledge that their local officers are systematically working to solve neighborhood problems – the police chief only wants to know the degree to which the district’s public is reassured.

Second, by not emphasizing some of the most traditional measures of effort and output, the framework avoids sending a mixed message about whether it is necessary to perform those kinds of activities at some specified level, in order to avoid getting in trouble. The intention is to encourage the district/precinct unit and its commanders to emphasize the achievement of important outcomes, and to give them reasonable flexibility in determining how best to do it. The measures do not discourage the use of motorized patrol, quick response, or making arrests; they just do not send a message to the district/ precinct that some level of those activities is required. It will inevitably be recognized by district/precinct commanders that some level of motorized patrol is probably necessary for public reassurance, that slow response to emergencies will result in low customer satisfaction, and that too few arrests might allow crime and disorder to increase. Thus, including these kinds of measures in a district/precinct performance measurement framework is probably not necessary – they will happen regardless.

Third, the truth is that someone, somewhere in the police organization will be measuring miles driven, response times, and arrests anyway. If customer satisfaction in a district/precinct declines, the unit commander as well as his or her bosses at headquarters will want to know why, and response time data may (or may not) provide some of the explanation. Lots of effort and output data are routinely generated and stored within police organizations, and can be used to diagnose and analyze unit-level performance-related problems. The framework above simply suggests avoiding most of those types of measures for the ongoing review of unit performance, especially core operational units, such as a district or precinct, whose performance is directly tied to the accomplishment of most of the overall organization’s primary missions.

Repeat Offender Unit

One type of specialized police operational unit is a repeat offender unit (Martin and Sherman 1986; Abrahamse et al. 1991). Typically, this type of unit targets repeat offenders, also called prolific offenders. The underlying rationale is that some offenders commit a disproportionate number of offenses. The earlier in such offenders’ careers that police can identify, arrest, and successfully prosecute them, the quicker they come under correctional supervision (including incarceration), and therefore the fewer offenses they will be able to commit. Similarly, if offenders are released from jail or prison and resume a prolific career, the sooner police rear-rest them, the fewer offenses they will be able to commit.

Police repeat offender units usually target robbers, burglars, and thieves, as these are high-volume crimes, although other types of offenders may also be targeted, and it is not uncommon for targeted offenders to commit a variety of types of crimes, to be drug offenders as well, and/or to be gang members. It is not unusual for such a unit to conduct surveillance on a suspected active robber and catch him in the act of a theft or drug purchase. Methods for targeting often include plainclothes operations, surveillance, sting operations, and the use of informants.

One other method used by repeat offender units is to conduct enhanced investigations following the arrest of offenders who qualify under “three strikes” laws as career criminals or prolific offenders (criteria vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction), whether these offenders are arrested by the unit or by other officers in the police department. These enhanced investigations are intended to build stronger cases on the instant offense, as well as assemble the necessary documentation to prove to the court that the individual meets the eligibility criteria for an additional sentence under the three strikes law.

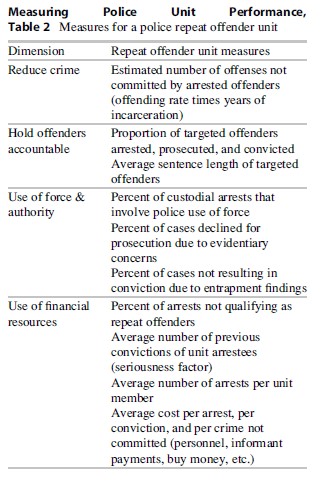

As described, the responsibilities of a repeat offender unit are fairly narrow, but they are directly tied to some of the overall police organization’s important dimensions of performance. A framework like the following one might provide a well-rounded picture of the unit’s performance.

This suggested framework includes ten measures, nine of which are within three of the seven dimensions of police performance. It does not seem reasonable to utilize measures related to reducing fear, ensuring civility, and satisfying the public when assessing the performance of a repeat offender unit, simply because the unit’s functions are not tied closely enough to these outcomes. It is anticipated that the unit’s activities might contribute to crime reduction, but care needs to be taken since such a unit is usually comprised of just a few officers/detectives – expecting the impact of their work to be detectable on the overall crime rate in the jurisdiction is somewhat unrealistic. The suggested measure focuses on the crimes not committed by the offenders who are arrested by the unit. Of course, the measure is nothing more than an estimate. But if a robber who has been committing ten robberies a year is incarcerated for 3 years, it is not too unreasonable to give the unit credit for preventing thirty robberies from occurring.

The other nine measures try to get to the heart of the repeat offender function. Reflecting the basic issues of productivity and effectiveness, they focus on whether the unit is successful in arresting, prosecuting, and convicting the repeat offenders that are targeted. Recognizing one important negative consequence of this type of strategy, they focus on whether the unit is able to operate within the law. Similarly, they focus on whether the unit is able to maintain its focus on repeat offenders, rather than broadening its criteria and making arrests of less significant offenders – experience has shown that this kind of “mission creep” often occurs, especially if the unit feels pressure to produce larger quantities of arrests in order to justify its existence. Lastly, the measures incorporate some cost criteria. These are particularly important because, again, experience has shown that repeat offender units tend to be costly on a per-arrest basis, because their tactics are personnel-intensive. However, on a per-conviction basis, or in relation to the seriousness of the offenders who are arrested, the cost of the unit’s performance may be rated more favorably.

A question might be raised as to why arrests figure so prominently in the repeat offender unit’s measures, when they were not suggested among the district/precinct measures. The response would be that the repeat offender unit’s narrower function is directly focused on identifying and apprehending particular offenders, whereas the district/precinct’s function is much broader – so much so that the number of arrests made by the district’s or precinct’s officers might or might not contribute positively to the achievement of its desired outcomes.

Communications Center

One type of support unit within a police organization is the communications center. This unit normally answers telephone calls to the police agency from the public, including emergency calls, and also uses the police radio system to dispatch police officers to incidents and to respond to inquiries from police officers in the field. The communications center may also be the hub for inquiries to databases on wanted persons, vehicle registrations, driver licenses, and so forth, although in many police agencies today, officers can initiate these kinds of inquiries themselves via hand-held computers or computers in their patrol cars, without requiring any assistance from dispatchers.

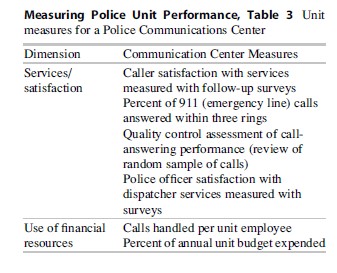

A police communications center does interact directly with the public, mainly via the telephone, but otherwise its performance is entirely in support of other units of the organization. Because the communication center’s performance is only indirectly tied to the accomplishment of a majority of the overall organization’s desired outcomes, it is not reasonable to use most of those seven categories when measuring the performance of the unit. A framework like the following, emphasizing two of the seven categories, might provide an adequate indication of the unit’s performance.

This framework includes six measures, four associated with providing quality services that satisfy customers, and two related to efficient use of resources. The main emphasis is on measuring the quality of services provided to the communications center’s primary clientele – members of the public who call to request assistance or seek information, and police officers who interact with dispatchers over the police radio system. The quality control assessment mentioned in the measures reflects a common practice in the communications field. Telephone conversations are routinely recorded, and a sample is later reviewed, either by supervisors or quality assurance specialists, using a standard rubric.

Comparisons, Benchmarks, And Standards

This research paper has focused mainly on measuring police unit performance, but a brief discussion of analysis and interpretation of the measures is in order. A few of the measures identified above are meaningful on their face, such as the percent of the unit budget expended, which is expected to be 100 % or less. If it exceeds 100 %, the unit manager would likely be required to explain why the budget was exceeded. Any subsequent action would probably depend on the explanation.

Most of the measures of police unit performance become meaningful through comparison. As an example, 75 % of the recipients of police service in a police district/precinct might report that they were satisfied with the services they received, or 75 % might report that the officer treated them with respect (the specific survey items used to measure customer satisfaction are likely to vary from one organization to another). The question then arises, is 75 % a good score? Does it indicate that police performance in the district/precinct is excellent, satisfactory, or in need of improvement? Without any additional context, we would likely conclude that performance is fairly good, but not fantastic. But interpretation could become much more meaningful by making two types of comparisons: (1) comparison to all the other districts/precincts in the same police organization, and (2) comparison to previous reporting periods (years, in most cases). Such comparisons would reveal whether the public’s satisfaction with police services received in the district/precinct is higher, about the same, or lower than in other districts, and also whether it is improving, staying the same, or declining over time. These kinds of simple comparisons typically add a great deal of meaning to most of the unit performance measures described above.

A third type of comparison is external. Comparing performance in one police department to others is usually done at the organizational level, such as comparing crime rates and clearance rates. Particularly when scores on performance measures are published, they can serve as benchmarks to which a police organization can easily compare itself. This becomes somewhat more challenging at the police unit level, in part because such data are rarely published, and in part because similarly named units in two different police departments may not actually perform the same duties or have comparable resources devoted to the functions. Nevertheless, a police communications center, for example, could identify other police agencies that also measure the proportion of incoming emergency calls answered within three rings, or even participate in a consortium of agencies that agree to collect data on the same unit performance measures. Establishing a system that enables such external comparisons of performance would be very valuable for the police communications center manager, allowing she or he to gauge much more accurately how well the unit is performing, and which aspects of performance might be most in need of improvement. Naturally, this kind of performance information would also be extremely useful for higher-level executives who, otherwise, would have a difficult time determining whether their department’s communications center is performing as well as it should.

An additional form of comparison is sometimes available when recognized standards of performance have been established. Within a police organization, for example, a standard of three minutes or less might be established for average response time to high-priority calls. This might be an organization-wide standard monitored monthly or annually, but it could also be applied to districts/precincts. When a performance measure includes such a standard, a message is sent to unit managers that they should allocate their resources and direct their personnel in such a way that the standard is met. If a unit does not meet such a standard, its manager knows that a convincing explanation will be expected, and in fact, the manager should be able to point to efforts made to meet the standard, and should have notified his or her superiors in advance that the unit was at risk of not meeting the standard.

External standards of police performance are potentially the most powerful, but they are rarely available. A standard-setting body does exist, the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies (CALEA). However, the commission’s standards primarily address administrative processes rather than true performance standards. For example, a CALEA standard requires periodic audits and inventories of evidence and property under the control of the police agency. The standard has some specific requirements, such as a minimum of an annual audit and a required audit whenever a new person is assigned to the position of property custodian. But the standard does not specify that the audit must be able to account for 100 %, or 99 %, or 95 % of the evidence and property that is supposed to be in storage. Similarly, a standard specifies that “if the agency participates in a tactical team, the agency requires that all personnel assigned to the team engage in training and readiness exercises.” CALEA standards do not specify how much training, though, nor do they set any kind of standard for the tactical team’s actual performance.

Despite the general lack of external performance standards for police units, it is practical and feasible for a police organization to establish a robust system for measuring the performance of its subunits, as described in this research paper. Certainly there are challenges to both measurement and interpretation, but establishment of such a system is essential for effective police administration, accountability, reform, and ultimately, for the delivery of quality services and adequate protection to the public.

Bibliography:

- Abrahamse AF, Ebener PA, Greenwood PW, Kosin TE (1991) An experimental evaluation of the Phoenix Repeat Offender Program. Justice Quart 8:141–168

- CALEA (2012) Standards for Law Enforcement Agencies: The Standards Manual of the CALEA Law Enforcement Accreditation Program, Fifth Edition as revised. Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies, Gainesville, VA

- Cordner G (1978) Open and closed models of police organizations: traditions, dilemmas, and practical considerations. J Police Sci Administr 6(1):22–34

- Davis RC (2012) Selected international best practices in police performance measurement. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

- Eterno JA, Silverman EB (2012) The crime numbers game: management by manipulation. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

- Fleming J, Scott A (2008) Performance measurement in Australian police organizations. Policing: J Policy Practice 2:322–330

- Henry VE (2002) The Compstat paradigm: management accountability in policing, business and the public sector. Looseleaf Law Publications, Flushing, NY

- Hoover LT (ed) (1998) Police program evaluation. Police Executive Research Forum, Washington, DC

- Langworthy RH (1999) Measuring what matters: proceedings from the Policing Research Institute meetings. National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

- Lind RC, Lipsky JP (1971) The measurement of police output: conceptual issues and alternative approaches. Law Contemporary Prob 36:566–588

- Martin SE, Sherman LW (1986) Selective apprehension: a police strategy for repeat offenders. Criminology 24:155–175

- Moore MH, Braga A (2003) The bottom line of policing: what citizens should value (and measure) in police performance. Police Executive Research Forum, Washington, DC

- Parks RB (1971) Measurement of performance in the public sector: a case study of the Indianapolis Police

- Indiana University, Bloomington, IN Reaves BA (2011) Census of state and local law enforcement agencies, 2008. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

- Shane JM (2007) What every chief executive should know: using data to measure police performance. Looseleaf Law Publications, Flushing, NY

- Stone C, Travis J (2011) Toward a new professionalism in policing. New perspectives in policing. National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

- Sunshine J, Tyler TR (2003) The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law Soc Rev 37:513–548

- Weisburd D, Neyroud P (2011) Police science: toward a new paradigm. New perspectives in policing. National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.