This sample Money Laundering Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Laundering money entails disguising the illicit origins of proceeds of financial manipulation, drug trade, fraud, corrupt enrichment, or other crimes, bringing back money into the financial circuit of the legal economy. Some underlying misbehavior, the so-called predicate offense generates illicit gains which are to be turned legal. Hiding or disguising the source of these proceeds will not amount to money laundering unless they were obtained from a criminal activity (Busuioc 2007).

Predicate offenses for laundering can be “hard” crime involving drugs or violence, but may also be white collar crimes, such as illicit real estate dealings, fraud and embezzlement, and finally tax fraud and tax evasion. Laundering the resulting (typically large amounts of) money can be achieved through fake invoicing for exports and imports or unusually priced real estate transactions. Disguising is further attempted through pumping money around foreign banks (typically in tax haven countries), through gambling or buying expensive consumer goods which can be moved around without effective controls (e.g., diamonds, highly priced art, or yachts). Each of these innovative ways of spending money (which can be recovered in legal markets) may require a different set of expertise of the investigation agencies: It might be the criminal police, customs, or forensic auditing firms. In many cases, only a combination of these might be able to trace these complex crimes.

With the growth of financial markets and instruments, money-laundering constructions have become ever more sophisticated. Swaps and other derivatives can be involved; multiple housing transactions and complicated insurance instruments can blur the origins of the illegal proceeds. Take, for example, a real estate agent collecting say 10 million dollars from a tax evader in cash money for selling a business complex. The listed price of the object is 5 million dollars; the true price is 15 million dollars. The real estate agent takes the cash money to his or her bank and transfers this money to his abroad company X, who in turn gives a fake loan of 10 million dollars to a company Y. Company Y pays back the fake loan to company X. The real estate agent now has an official receipt of income of his company X of 10 million dollars. Tax evading now results in an object bought worth 15 million dollars of which only 5 million in official money has been paid, the rest with laundered money. When the object is sold again, there are official sales receipts for 15 million dollars. Finally, the tax evader has a non-traceable supposedly legal revenue of 10 million dollars which can be spent on investments in business, hotels, or for luxury consumption of cars, jewelry, and real estate.

Money laundering, however, owes its name to a much simpler technique dating back to Chicago gangster Al Capone. He used the cash-intense business of launderettes to hide his illegal alcohol proceeds in times of prohibition in the 1930s. Slipping money from alcohol proceeds into the cash register of his launderettes, he pretended this was turnover of the regular business. By 2009, money laundering is estimated to amount between 1.5 and 3 trillion US dollars that circulate across the globe as illegal money transfers (see Walker 1995; Unger 2007; Walker and Unger 2009; Review of Law and Economics 2009). With the exception of the group around Truman and Reuter (2004) who think that the estimates of laundering are exaggerated, money laundering is considered a huge global phenomenon.

Laundering transfers can take place using the banking sector. They can use transfers by regular invoice or payment including new electronic methods like digital cash, e-gold, or prepaid phone cards (see http://www.fatf-gafi.org). Pressure from national regulators has led to the introduction of more electronic control systems. Financial institutions set barriers for the transfer of larger amounts (such as 10,000 dollars in cash or unusual transfer) which are to be checked for their source or purpose. Gambling casinos are obliged to control the identity of customers who invest unusual amounts of cash. Internet gambling, however, can easily avoid national borders and controls.

Such controls are devised to detect the predicate crime. The United States has developed a list of more than 130 predicate offenses suspect for money laundering. More predicate offenses were added into the money laundering definition over the years. Upon political requests, also terrorist financing and lately tax evasion have been included (see: FATF 2010). As a consequence, the amount of laundering has increased by definition.

Setting Money Laundering On The International Agenda

Money laundering is a relatively young topic and only recently an issue on the international agenda (see Unger 2007 for a survey of the money laundering literature). Sure, already in ancient Chinese trade, there were other forms of hiding proceeds from authorities and there were punishments for dealing in stolen goods (“fencing”). However, money laundering in its current meaning dates back to the 1980s when it was first criminalized in the United States.

Fighting drug dealing has for a long time been of central concern in combating money laundering. After several decennia of the unsuccessful US “War on Drugs,” the Clinton Administration chose a hard crime fighting approach: If drug dealers and other criminals could not got caught directly, at least they should be discouraged by not being able to reap the monetary benefits of their dealings (see Unger 2011). Thus, in 1986 (Title 18, US Code Sec. 1956), money laundering got punished in the USA with up to 20 years in prison and $500,000 in fines. Further legal arrangements permitted seizing, freezing, and confiscation of assets by the authorities.

Since money laundering is a global crime without borders, the USA made large efforts to convince the international community of the importance of the topic. On a global level, anti-money-laundering policy started in the late 1980s with the UN Convention on Drug and Narcotics of 1988. In 1989, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an intergovernmental body to combat money laundering, was established by the G-7 countries. Since then the global movement against money laundering steadily gained support. Today, the FATF comprises of 34 member jurisdictions and two regional organizations, representing most major financial centers in all parts of the globe. The combat accelerated after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, when getting hold of terrorists by combating the financing of terrorism became part of anti-money-laundering policy.

However, one principal objection to FATF’s work is its nondemocratic character. Groups of experts are nominated by their governments; they are not accountable to any parliament, and nobody can dismiss them. In such an “expertocracy,” some countries send delegates to FATF meetings who may not be fully aware which enormous consequences these meetings can have on their national legal system and institutional setting.

Hindrances For Compliance: Victimless Crime And Unproven Effects

Money laundering itself does not seem to have direct victims. No individual suffers from the Colombian drug mafia sending 10 billion dollars from one country to another; on the contrary, many might rightfully profit from the resulting business. There are no victims who would complain, no liability claims that would be raised, and no tort law that could be applied. Legal literature therefore debates whether crime without victims should be punished at all and whether punishment is a deterrent. Would society be damaged by this maleficent behavior and fall into decadence (Mill, Chapter 1, p. 21)? The damage incurs on the level of the common goods of society. “Public order crime” would be the preferred term in place of “victimless” crime.

The harm of money laundering is indirect. Unger (2007) lists 25 negative and positive effects that money laundering can have. It can deter honest business activities: If criminals invest their money in particular sectors like the transport industry, restaurants, housing, it can lead to changes in relative prices, savings, output, employment, and growth or it can affect the liquidity, reputation, integrity, and stability of the financial sector. The public sector can suffer from unpaid taxes and criminals might buy up public enterprises during privatization efforts. There are also social and political effects, such as increased corruption and bribery. Criminals might undermine political institutions: As laundering needs facilitators, professionals such as lawyers, notaries, real estate agents, and accountants can become contaminated. None of these effects, however, can be observed directly which renders it difficult to prove. Reaching compliance for anti-money-laundering policy needs the backing of civil society.

Development Of International Anti-Laundering (AML) Standards That Need Compliance

For larger amounts which are dealt within international finance, the FATF sets international standards, which, in order to comply to, member countries have to arrange for enforcement and execution. Lawyers in ministries, policemen, public prosecutors, and judges may be involved in antiterrorism and money-laundering combat. Special organizations, called Financial Intelligence Units (FIU), have to be established in each country. Countries have to introduce plans to implement ongoing customer due diligence (CDD), identify nondomestic politically exposed persons (PEPs), and ascertain identification of beneficial ownership of offshore accounts. Banks, real estate agents, notaries public, traders in large values are obliged to screen their clients and to identify persons, activities, or transactions suspicious of money laundering or terrorism financing among their clients. The FIU collects their suspicious transaction reports. Supervisory authorities are involved to control the compliance of banks and other sectors with the anti-money-laundering regime (AML). Some countries, such as the USA, have high sanctions for not reporting, with fines as great as $250,000 or 5-year imprisonment (IRS 2011).

However, there has also been criticism of too harsh penalties. Takats (see Masciandaro et al 2007) warned stricter sanctioning might lead to a “crying wolf problem,” referring to the boy who always cried wolf but once the wolf really came nobody paid attention. The private sector might, from fear of being punished, drown the FIU by reporting all sorts of transactions as suspicious without indicating what might a predicate offense.

Multiple Actors Involved In Money Laundering

The money-laundering process may be divided into three phases. In the placement phase, the criminal, after he has committed the predicate crime, such as selling drugs, committing fraud, working illegally, or producing fake brand products, wants to get rid of the criminal cash. He or she tries to hand the proceeds of crime over to a person from the “upper world.” This can be putting it into the cash register of a launderette as Al Capone did and bringing it to the bank as legal proceeds from washing people’s laundry, bringing illegal cash to a bank employee who accepts a suitcase of cash money, to a company who issues fake invoices, or to a transport entrepreneur who transports cash as a courier to another country where it is placed at a bank. Other actors involved in this first phase may be bank employees, business owners, or employees from the transport sector, the restaurant business, etc. After, the second phase called “layering” starts, which tries to make it difficult to detect the illicit proceeds. Transfers may be wired; offshore banks may be involved; fake shell companies may pump the money around the globe. Here the international financial sector would be involved. In the last phase, the integration phase, the money is parked in either financial investment and business. Actors involved may be real estate investors or notaries who are involved in buying and selling houses and accountants in companies, tax advisors, etc. Smaller amounts which could possibly be carried in cash might be laundered by luxury consumption or gambling. Actors involved might be dealers in diamonds or cars, custom officials, etc.

All private sector actors listed, such as bank employees, accountants, tax advisors, dealers, notaries, and lawyers, can get consciously or unconsciously involved in money-laundering transactions. Complicity is an offense wherever laundering is prosecuted. It is the task of all professional services involved to stay alert to money-laundering transactions and to report suspicious transactions to public authorities. Their commitment can be either voluntary, as to help fighting crime, but increasingly statutes try to enforce it by reporting duties and threat of punishment.

Compliance Of A Great Variety Of Actors

Combating money laundering is as strong as its weakest link in the chain. Coordination and compliance of many policy actors is crucial. Diverse actors for whom the policy is not necessarily given priority or not even in their own interest must be brought into one line. Unlike food or tobacco regulation, combating money laundering does not have a private sector lobby. It is governments and with them the media engaging in a fight against laundering. Not all governments are however as active in engaging in the combat. For some countries, it can be beneficial to attract criminal money. Unger and Rawlings (2008) speak of the “Seychelles effect,” referring to the island state which in the 1990s deliberately advertised that if investors invested more than ten million dollars, they would not check where the money came from. As they are hardly confronted with the underlying crime, offshore islands and small countries may see the incentive of attracting criminal money. Large countries on the other hand often attract a bigger volume of laundering due to their financial centers and expertise (see Gnutzmann, McCarthy and Unger 2009).

By membership of the FATF or belonging to a FATF-Regional Style Body, states are obliged to implement international standards of anti-money-laundering policy, even though there are divergent national interests – some are tax havens and profit, others suffer from the experience of crime. Lack of a common interest among countries and the divergence of who bears the costs and who the benefits of the combat against money laundering makes it difficult to effectively implement anti-money-laundering policy. Seeing the variety of actors, different ways of circumvention and peculiar forms of compliance can be expected.

Public Actors Involved In Combating Anti-Money-Laundering

Governments must implement the international standards of FATF into national law. For some countries, this can pose a legal problem. Exportintensive countries such as Austria, Germany, and the Nordic countries feared double punishment for laundering money as well as the underlying crime and therefore originally excluded self-laundering from the money-laundering definition. In the FATF Third Mutual Evaluations of Austria and Germany, authorities explained that the predicate crime includes the concurring act, the laundering, and that the sanction set for the predicate crime is deemed to cover the entire unlawfulness of the criminal’s act (FATF 2010). Most of these countries had to revise their money-laundering definition due to pressure of the FATF. In strongly legalistic countries, this change in the principles of law might lead to resistance when practicing the law, so that law in the books and law in practice diverge. Compliance would here be only in the books but not in practice.

Combating money laundering goes from designing the national anti-money-laundering law(s) to the establishment of an FIU. It can be located at the Ministry of Finance as financial intelligence unit, at the Ministry of Justice, the police, or at the Central Bank. It receives reports of suspicious transactions from the private actors, especially from banks and the financial sector, and has to screen these reports. A finance person may concentrate on different reports than a police officer used to hunting drug dealers. The FIU located in the Ministry of Finance might be more inclined to identify tax fraud, while the police might be more after corruption and drug cases. Thus, data access and the interpretation of data vary widely among the different FIUs.

The further chain of judicial procedures can be frustrating if police investigations are judged to deliver insufficient proof. Reports found sufficient by the investigators are sent to the office of public prosecutors who may decide whether to indict and proceed with an accusation or to drop the case, either because of lack proof or because of lack of legal relevance. In principle, the prosecution has to prove suspects guilty, but in some countries, the judge may allow for reversal of the burden of proof about where a big amount of money (relative to the suspect’s means) came from.

An effective indictment presupposes all public actors, the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary are willing and able to recognize anti-money-laundering policy as an important goal to pursue and that they are willing and able to cooperate. They should have a similar understanding of the goals of anti-money-laundering policy and how it can be practiced in each country. Compliance policy will be counteracted from within, when public actors are themselves involved in money laundering: such as may be the case when government officials or customs and police officers are part of the laundering gang.

Reporting And Supervision

Anti-money-laundering policy requires penal codes which clearly define offenses and punishment as well as an active enforcement administration. If private actors (such as banks) are obliged to report suspicious transactions to the FIU, noncompliance may risk high fines (as in the USA) or even a jail sentence (as in Luxembourg).

Reporting obligations bring into life reporting systems. Banks and financial institutions may have to establish a software system to recognize suspicious transactions including compliance officers who can be held responsible. They have to check on lists of internationally blacklisted persons and companies, to fill in forms and forward them to the FIU, sometimes for privacy reasons handing them over personally. In short, the reporting system is costly and cumbersome for the private sector. As the private sector has no particular interest in fighting money laundering (there is no private sector lobbying for this policy issue) and in so far as compliance poses extra costs, it might be difficult to be reached.

Supervision of reporting entities is important. Many supervisory authorities are engaged in supervising reporting. In many countries, the Banking Supervision Authority also supervises anti-money-laundering matters. But do they find money laundering as important as, for example, the Financial Intelligence Unit might find it? Lawyers are usually supervised by their Bar Association which might put more emphasis on legal privilege and privacy of customer relations. In some countries, the FIU itself supervises. It remains doubtful whether the FIU knows enough about diverse sectors in order to supervise banks, financial service sectors, accountants, car dealers, and diamond dealers. Countries differ with respect to the competent actor for supervision. Some agencies might be centrally organized, others at a state or provincial level.

Hindrances To Compliance

Anti-money-laundering policy is mainly a public sector concern; hence, the private sector needs to be persuaded to collaborate. This means both good relations between the public and private sector as well as strict laws, punishment, and supervision should be in place. However, some countries benefit from the underlying crime while others bear the costs it. Disinterested countries may need to risk international sanctions or receive side payments in order to combat money laundering. As long as some countries hunt drug dealers but stick to bank secrecy while others fight tax evaders, compliance lacks a common policy goal to which one should comply.

Private actors have different priorities and often a double relationship: A launderer is also a client of banks and lawyers. Reporting a client with a close relationship to a bank (particularly when cash business is involved) means losing money, while not reporting may entail reputation damage to the bank. Similarly, there is the legal privilege of lawyers and notaries, which guarantees privacy of the lawyer-client relationship. Reporting a client therefore becomes a delicate balance between reporting duty and right of legal privilege, which might be very difficult to supervise and actors involved are definitely not interested in cooperation.

Seeing the many reasons why the private sector might not comply with anti-money-laundering policy, and seeing the many ways in which anti-money-laundering policy might be circumvented, the FATF has opted for blacklisting as a drastic step of enforcement.

Blacklisting Countries For Noncompliance

Many institutions, among them all central banks of the OECD countries (18 members) as well as the European Union, are maintaining white lists of countries: countries which are cleared for controlling their banks and financial institutions as well as multinational corporations for money-laundering transfers. Transfers from countries which are cleared may be accepted on the basis of simplified identification research of their financial institutions.

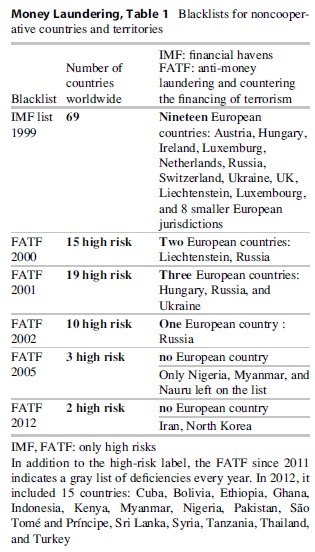

Similar lists, only with a reversed definition as black lists of countries with insufficient controls, are issued by the FATF (23 members). It has issued forty anti-money-laundering recommendations for controlling the financial sector and nine recommendations for combating terrorist financing. Countries face regular mutual evaluations and in case of noncompliance with the recommendations, they can get blacklisted as noncooperative countries (Unger and Ferwerda 2009). This can be economically very harmful, since countries risk that no American bank will do business with them. It is doubtful, however, whether blackmailing dogs really want to bite. In a first evaluation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1999 when a definition of financial havens was used, 69 noncooperative countries were listed, among them 19 European countries such as the financial centers of the UK, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Luxembourg. This cross-border transfer of capital leads to extraction of capital in countries where the crime is committed and leads to an inflow of capital in countries where the integration phase takes place. The IMF (with 188 members including developed as well as developing countries) stopped their rankings because they felt that they could not take into account both ends of the chain. Consequently, they criticize the FATF (with 18 predominantly richer members) which simply checks the financial control infrastructure by intergovernmental assessments (Table 1).

And indeed, on the FATF list of noncooperative countries, none of the financial centers are listed. The first official FATF rating in 2000 lists 23 countries, later blacklists included only 15 noncooperative countries of which two were European: Liechtenstein and Russia. Eventually the list got shorter and shorter. In 2006, Myanmar was the only noncooperative country left, and was finally also removed from the list in October 2006. The regular mutual evaluations of the FATF look for “risks of anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism.” As soon as the Financial Control Agency cooperates (such as the financial center countries), the country does not appear on the blacklists.

The FATF blacklist was heavily criticized for its lack of transparency and legitimacy, as it did not rate all countries and was biased against small countries (Unger and Ferwerda 2009). Since 2011, there is a new “gray list” which distinguishes in four categories in how far they are fulfilling the FATF recommendations (either fully, making efforts in the right direction or not having made any effort for change). Countries make great efforts to be removed from this list, but this might show only “shallow compliance” in the books instead of effective action. They might strategically produce statistics to satisfy the FATF (such as by just reclassifying cases or counting a case with several transactions by each transaction separately).

Bibliography:

- Baker R (2005) Capitalism’s Archilles heel: dirty money and how to renew the free-market system. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley

- Busuioc EM (2007) Defining money laundering. In: Unger B (ed) The scale and impacts of money laundering. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham/Northampton, pp 15–280

- Deleanu I, van den Broek M, Ferwerda J, Unger B (2011) Performing in the books, assessing countries’ antimoney-laundering policy in the light of strategic reporting. Paper presented at the ECPR Conference 2011 in Reykjavik, Iceland. http://www.ecprnet.eu/ MyECPR/proposals/reykjavik/uploads/papers/2734.pdf

- FATF (2010) Financial action task force report on tax crime, Third round mutual evaluation report on Germany, Paris

- Financial Action Task Force homepage. http://www.fatfgafi.org

- Gnutzmann H, McCarthy KJ, Unger B (2010) Dancing with the devil: country size and the incentive to tolerate money laundering. Int Rev Law Econ 30(3): 244–252

- IRS (2011) Suspicious activity reports. Retrieved from http://www.irs.gov

- Masciandaro D, Takats E, Unger B (2007) Black finance: the economics of money laundering. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA

- Sabitha A (ed) (2009) Combating money laundering. Transnational perspectives. Amicus Books: The Icfai University Press

- Tackling money laundering, Special issue of Rev Law Econ 5(2):807–985. December 2009

- Truman E, Reuter P (2004) Chasing dirty money: the fight against money laundering. Institute for International Economics, Washington, DC

- Unger B (2007) The scale and impact of money laundering. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA

- Unger B (2011) Regulating money laundering: from Al Capone to Al Qaeda. In: Levy D (ed) Handbook of regulation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA

- Unger B, den Hertog J (2012) Water always finds its ways. Crime Law Social Change 57:287–304

- Unger B, Ferwerda J (2011) Money laundering in the real estate sector. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham. 2011 Review of Law and Economics, Special Issue on Money Laundering, Dec 2009. http://www.toezichtencompliance. nl/nieuws?cID¼914&PHPSESSID¼jdeaul6hts3u2cv6kdeubdhce6

- Unger B, Rawlings G (2008) Competing for criminal money. Global Bus Econ Rev 10(3):331–352 United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC). www.unodc.org

- Walker J (1995) Estimates of the extent of money laundering in and through Australia. Paper prepared for the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre, Sep 1995. John Walker Consulting Services, Queanbeyan

- Walker J, Unger B (2009) Estimating money laundering: the walker gravity model. Rev Law Econ December

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.