This sample Police-Led Interventions to Enhance Police Legitimacy Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

A growing body of policing research demonstrates that procedurally just approaches to policing – including satisfaction, trust, and confidence – improve citizen perceptions of police, thereby influencing perceptions of police legitimacy and facilitating the capacity of police to maintain order and control crime. This research paper draws from a systematic search of police legitimacy and presents a qualitative overview of 104 evaluations of policing interventions that sought to improve police legitimacy. Mazerolle and colleagues (2013) used content analytic methods to synthesize the extant literature, examining studies that used either a processor instrumental-based approach to enhance perceptions of legitimacy. In this research paper, it is shown that some interventions, notably those that are policeonly type interventions, seek to influence legitimacy primarily through their efforts to be more effective. In contrast, interventions that involve partnership approaches tend to directly influence perceptions of legitimacy by increasing efforts to enhance positive perceptions of police. Overall, it is shown that different process-and instrumental type policing strategies seek to improve police legitimacy in a variety of ways.

Fundamentals

An extensive and growing body of international research focuses on police legitimacy: that is, the expectation that the police will be obeyed, over and beyond the threat of punishment or expectation of reward (Tyler 2006). Several theoretical pathways have been proposed for the relationships between police activity and police legitimacy. The process model of police legitimacy holds that when police use the key ingredients of procedural justice – allowing citizens to participate in decision-making, treating people with dignity and respect, maintaining neutrality, and acting with transparent motives – this leads to enhanced citizen perceptions of police, including trust, confidence, and satisfaction with police, and thereby increased levels of police legitimacy (Hinds and Murphy 2007; Mastrofski et al. 1996; McCluskey 2003; Reiss 1971; Sunshine and Tyler 2003; Tyler and Fagan 2008; Wells 2007). Increased police legitimacy then encourages compliance with both police directives and the law, thus indirectly affecting crime and disorder (Tyler and Fagan 2008; Tyler and Huo 2002). The instrumental model of police legitimacy, in contrast, posits that police effectiveness in controlling crime and disorder is a key antecedent to police legitimacy, and thereby perceptions of effectiveness influence citizen perceptions such as satisfaction with, and trust and confidence in, the police (Sunshine and Tyler 2003).

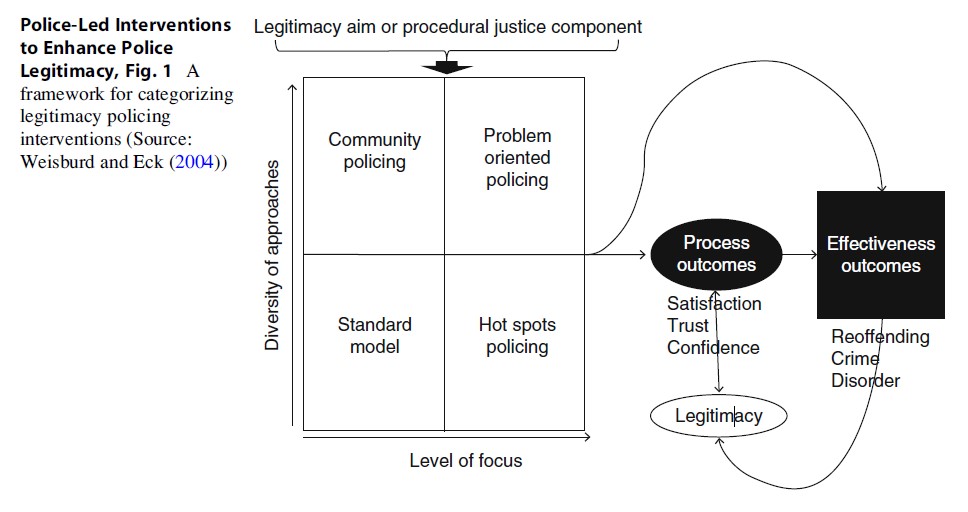

The causal pathways proposed in these legitimacy models show that police use a number of different intervention strategies – which are either process-focused or outcome-focused – in their efforts to enhance perceptions of legitimacy. One way to situate the variety of police interventions that seek to enhance police legitimacy is to use a typology developed by Weisburd and Eck (2004). These authors describe policing strategies on two dimensions: diversity of approaches and level of focus. They identify four broad categories of police interventions: first, community policing, broadly defined as those interventions that involve police partnerships with the community, employ a highly diverse portfolio of approaches, and are loosely focused around general crime problems; second, problem-oriented policing, broadly defined as those interventions that, again, involve police partnerships but are highly focused on discrete problem people or places; third, hot spot policing, defined as those police interventions that are highly focused on problem people or places but have little diversity and few partnerships with other agencies; and finally, the standard model of policing, defined as police interventions that neither involve diverse partnerships nor a specific focus on problem people or places.

In this research paper, the heuristic of the Weisburd and Eck (2004) typology of policing interventions is used to compare and contrast different policing approaches used to enhance citizen perceptions of police legitimacy, drawing from a systematic search of the extant literature that identified 163 studies out of over 20,000 abstracts reviewed that met the review criteria (see Bennett et al. 2009). Content analytic methods were used to group strategies, identifying a subset of 104 studies that included evaluation information that could be used in a narrative review. These interventions are examined, based on their area of focus and diversity of approaches, in order to illustrate the varying impact of process-focused or outcome focused models of police legitimacy.

Key Issues

Scholarly interest in police–citizen interactions, perceptions of police treatment, and the legitimate authority of the public police is not new (e.g., Bayley and Mendelsohn 1969; Bellman 1935; Decker 1981; Parratt 1938; Reiss 1971). However, it is the contemporary stream of research by Tom Tyler and his colleagues that spearheaded renewed interest in police legitimacy and continues to shape the field today (see Tyler 1990, 2003, 2004, 2006; Tyler and Fagan 2008; Tyler and Huo 2002). This recent body of research finds that citizens are more likely to comply with police directives when they view police as legitimate. Tyler and his colleagues also show that police legitimacy encourages law-abiding behavior not just during a police– citizen encounter but also outside of encounters (i.e., in everyday life, such as abiding by traffic rules) (Sunshine and Tyler 2003; Tyler and Huo 2002). As Tyler (2004), p. 85 suggests, unless the police are “widely obeyed” by the public, the capacity of police to maintain order is compromised (see also Tyler 1990). Arguably, one of the most important contributions of Tyler’s research over the last 20 years is the deepening of our understanding as to how the efficiency and effectiveness of the order maintenance role of the public police is dependent upon the public’s support for, and perceived legitimacy of, the police.

Legitimacy is defined by Tyler (2006), p. 375 as “a psychological property of an authority, institution, or social arrangement that leads those connected to it to believe that it is appropriate, proper, and just.” The key defining feature of a legitimate authority is that people feel obliged to voluntarily comply with the authority’s directives as opposed to compliance out of fear of punishment or expectation of reward (Tyler 2006). In policing, legitimacy reflects a “social value orientation toward authority and institutions” (Hinds and Murphy 2007, p. 27), and evidence shows that it is a person’s belief in the legitimacy of the authority or institution issuing a command that “leads people to feel that the authority or institution is entitled to be deferred to and obeyed” (Sunshine and Tyler 2003, p. 514).

Procedural justice refers to the use of fair procedures in the decision-making process (Hinds and Murphy 2007; Thibaut and Walker 1975). Scholars across many different contexts and disciplines (e.g., taxation compliance and organizational behavior) have studied the impact of a person’s treatment in a range of different decision-making forums. In policing, renewed academic interest in procedural justice emerged during the late 1980s and early 1990s at a time of high-profile incidents of pervasive police corruption and police misconduct (e.g., racial profiling, excessive force) (Reiner 1985) and concerns about police inadequacies in dealing with upsurges in crime (Maher and Dixon 1999; Weisburd and Braga 2006), which led to a general loss of confidence in traditional police responses to crime (Weisburd and Eck 2004). These concerns created fertile ground for the study of police legitimacy and the concomitant study of police–citizen encounters based on fair and respectful processes and procedures. Tyler and colleagues identify four factors that define “procedural justice” in interactions between police and the public: citizen participation in the proceedings prior to an authority reaching a decision, perceived neutrality of the authority in his/her decision, whether or not the authority showed dignity and respect throughout the interaction, and whether or not the authority is perceived to have trustworthy motives (Tyler 2004; Tyler and Lind 1992).

Researchers have sought to differentiate between the effects of police legitimacy on subjective outcomes, such as citizens’ perceptions of police, or intent to comply, and objective outcomes, such as actual compliant behaviors or reoffending. The difference between citizens’ perceptions and actions is a crucial consideration in the design of police interventions and evaluations of these interventions. While it is neither the purpose of this research paper to explore the complex relationship between legitimacy and procedural justice further nor to compare operational definitions and measurement methods, this is a highly important area of research. In this research paper, authors’ identification of legitimacy and procedural justice is accepted and the distinction between process outcomes (such as citizen satisfaction) and instrumental outcomes (such as reoffending) is used to classify intervention strategies according to their underlying logic.

The Systematic Search Approach

The results of a systematic search conducted on behalf of the UK National Policing Improvement Agency (NPIA) (Bennett et al. 2009) were used to obtain a population of studies evaluating police-led interventions to improve legitimacy. The systematic search covered a range of databases for published journal articles, as well as a search of the gray (unpublished) literature including reports and dissertations. Search keywords focused on police legitimacy, effectiveness, and procedural justice. The systematic search identified over 20,000 abstracts on police legitimacy and related topics. Readers are directed to the NPIA report for a full explanation of the systematic search and document retrieval strategy (see Bennett et al. 2009).

Information on any evaluation of police-led interventions was gathered from the 20,000 plus abstracts. These interventions had to either (1) explicitly aim to increase legitimacy or, (2) in the absence of an explicit legitimacy aim, use at least one of the principles of procedural justice: citizen participation in decision-making, police neutrality, dignity and respect, and transparent motives. Information from descriptive studies was also recorded to gain an understanding of initiatives that had been tried, even if they had not been evaluated. A pictorial explanation of the organizational framework (presented in Fig. 1) was used to guide coding and synthesis of the extant literature.

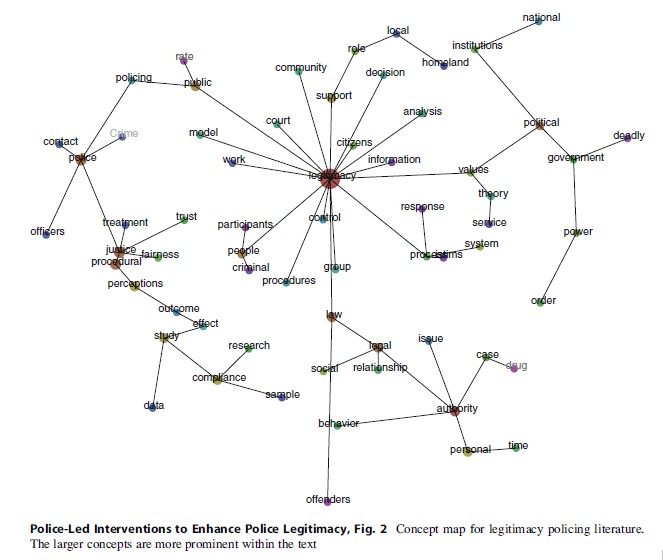

The systematic review of the identified abstracts revealed 163 sources that met the above criteria. Text analytics software (Leximancer: Leximancer software examines a body of text and produces a ranked list of concepts on the basis of word frequency and co-occurrence of usage (see https://www. leximancer.com/)) was used to create a map of the key concepts contained within the documents and to rank the most prominent concepts relating to policing within the body of text. The outputs from this analysis were used to compare whether, in the body of literature, the focus on the concept of legitimacy in the text matched the focus on the outcome of legitimacy in the evaluations. The conceptual structure of the 163 sources on police legitimacy interventions is presented in Fig. 2, below. As shown in Fig. 2, the central concept in the corpus of text was legitimacy, as would be expected given the goals of the search. The concept of legitimacy links directly to a large number of concepts, including the concept of police. The map suggests that within the body of studies, the concept of procedural justice is indirectly linked to legitimacy through the concept of policing. The semantic analysis showed that “crime” was the most prominent concept relative to the concepts of “police” and “policing.” The second most prominent concept related to policing was the concept of “trust,” with “justice” and “procedural” as the third and fourth most prominent terms, respectively. The most prominent compound term in the literature on police was “procedural justice,” with a relative frequency of 29 % and strength of 38 %. The content analysis thus demonstrates the centrality of legitimacy as a concept within this particular body of literature.

Systematic Search Findings

Of the 163 selected studies, 104 of the studies reported evaluation findings. All of the interventions included in this subset of studies articulated that the intervention sought to improve police legitimacy. The studies referred to in the following section, and the complete list of 163 studies, can be found in the Campbell Collaboration systematic review on legitimacy in policing (Mazerolle et al. 2013). The subset of studies included in our narrative review is organized using the typology articulated by Weisburd and Eck (2004) as follows.

Community-Based Policing Strategies

Community policing strategies fall into the top left quadrant of the Weisburd and Eck (2004) typology, characterized by a high diversity of approaches but low level of place or person focus (see Fig. 1). The review uncovered a number of legitimacy-enhancing strategies that fell into this category, including community policing, but also included interventions that were not strictly community policing interventions. These approaches tended to focus on the process model of increasing legitimacy directly through procedurally fair operations. Evaluations of these strategies therefore tended to focus on “soft” outcomes such as citizen confidence, satisfaction, and/or trust in police; perceptions of procedural justice; and police legitimacy. The following section discusses each strategy grouping in turn.

Community Policing

Community policing refers to a group of strategies that emphasize high-quality police–citizen interaction, especially in nonemergency situations, where police and community share responsibility for crime prevention and control (Bell 2004). Community policing is hypothesized to provide benefits over traditional policing methods, including increased public trust, satisfaction, and confidence in police; higher reporting of crime; more effective crime prevention; and better police– community relations (Bell 2004).

Community policing has been variously described as a philosophy, a strategy, or a series of tactics. For the purpose of the review, a number of elements commonly found in community policing strategies were drawn out. While most community policing strategies use one or more of these elements, not all elements are required for a strategy to be termed community policing. Skolnick and Bayley (1988) separate community policing elements into four categories. First, community-based crime prevention includes initiatives such as neighborhood watch, police safety seminars, and supplying security material to citizens (Bell 2004). Second, an emphasis on policing nonemergency situations includes routine motor, foot, or bicycle patrols and door-to-door activities. Third, increasing police accountability strategies include the development of specialist liaison officers for communication with minority groups, and programs that allow citizens to observe the police at work. Finally, decentralizing command within the police force and giving more power to officers actively policing the community is a key element of community policing. Other authors have identified additional elements, including the long-term assignment of officers to beats (geographic areas), community consultation to define community problems, reducing fear of crime, extended foot patrols, and an emphasis on nonconfrontational officer–citizen interactions (Fielding 2002).

The systematic search located 70 articles and reports on community policing-type strategies that fit within the Weisburd/Eck typology of diversity of approaches/low level of focus. The strategies included community policing grants and directives, reassurance policing, beat policing, proximity policing, contact patrols, ombudsman policing, mini-police stations and shopfronts, and neighborhood watch programs.

Overall, community policing was found to have a positive effect on a range of process outcomes, including citizens’ confidence in police, satisfaction with police, and perceptions of police effectiveness. Community policing initiatives also affected police officers’ views and internal processes such as increased levels of officer monitoring and accountability and holding positive views of mini-police stations. The successful creation of partnerships with community agencies was another benefit identified in the literature.

Not all evaluations were positive, however. For example, one researcher found that the introduction of proximity policing resulted in a decrease in confidence in police, due in part to an increase in administrative tasks to the detriment of time spent on physical patrols.

Evidence was mixed regarding instrumental outcomes for community policing. In terms of positive effects, several studies found a decrease in citizens’ perceptions of crime overall, disorder, and fear of crime. Others found decreases in perceptions of particular crimes. For example, some scholars found a decrease in the perceived levels of vandalism and graffiti, home burglaries, and drug dealing. Some social observational studies found a decrease in citizen noncompliance behaviors with police and also that citizen cooperation was higher for encounters with beat police compared to traditional patrols. In a series of evaluations of the Weed and Seed community policing grants, researchers found decreases in citizens’ self-reported revictimization in nearly all program sites, a finding paralleled in an evaluation of reassurance policing in English cities. Other measures of community policing effectiveness included citizens taking steps to improve their home security.

Again, however, not all studies found positive instrumental effects for community policing. One study found an increase in perceived crime levels, a decrease in perceptions of police fairness, and a large decrease in perceived safety. Other community policing evaluations found that community policing had no effect on either perceptions of safety or levels of official reported crime. One study found that an increase in official crime reports at sites with police shop-fronts was due to the increased willingness of shopkeepers to report crimes, rather than an increase in victimization.

Finally, the experimental literature is sparse and ambiguous regarding the effect of community policing on police legitimacy. Some authors have found no effect of community policing on legitimacy, while others have found a decrease in perceptions of police legitimacy after the implementation of a community policing intervention. Notably, these findings are contrary to nonexperimental survey research on procedural justice and legitimacy such as that of Sunshine and Tyler (2003).

School-Based Interventions

A second category of interventions that fell under the high diversity of approaches/low level of focus was school-based policing interventions that seek to reduce delinquency, antisocial behavior, and truancy by increasing police legitimacy through both process and instrumental paths. The review located six such interventions. Two of these described police officers whose activities were based primarily within one or more schools and who formed partnerships with the school community to enhance law enforcement, education, and counseling. Two sources described a program in which police officers visited schools and gave a talk on resisting gangs. One intervention focused on schoolchildren interacting informally with police officers in a nonconfrontational situation to increase children’s perceptions of police legitimacy, thereby increasing their willingness to assist police in the short and longer term. Finally, one source described a nonpunitive truant recovery program. Few implementation problems were reported for school-based interventions.

The overall evidence for school-based interventions was mixed. School-based interventions tended to measure success using instrumental outcomes, including willingness to assist police, grades and truancy, and police contacts and arrests. The truant recovery program decreased the number of fail grades, unexcused absences, school sanctions, and disciplinary reports for children in the program. However, school-based interventions had no significant impact on willingness to assist police, police contacts, or arrests. Further, schools assigned a police officer tended to have greater prevalence of truancy than schools without one, although the causal direction of this effect is not explicated in the group of studies collected. The informal contact program found a null effect on students’ perceptions of police legitimacy.

Interagency Collaboration

Another group of interventions falling into the high diversity of approaches/low-focus quadrant are those focusing on interagency collaboration, where police used formal arrangements with another organization (often a social service) to improve service delivery. These included police collaborating with a community mental health unit, with social workers following up on police domestic violence investigations; a multijurisdictional task force established for broad-based service provision; outreach workers working with sex workers at risk of violence; and a localized initiative aimed at reducing the prevalence of street walkers.

While interventions involving collaboration between multiple agencies frequently reported problems in implementation arising from differences between the agencies involved – such as different reporting policies and information retrieval systems – several studies reported improved information sharing and closer relationships between agencies as a result of the intervention.

The studies evaluating interagency collaboration effects on legitimacy tended to focus on instrumental outcomes rather than process outcomes. The intervention aimed at reducing the number of street walkers in an area was seen to be largely successful in achieving its goals, as well as improving police–community relations, and decreasing recorded street crime and fear of crime. Households that received a follow-up call from a social worker after a domestic violence incident were no less likely to experience violence than households that did not receive the call, but they were more likely to report new incidences of violence. The intervention encouraging sex workers to report violent clients achieved an increase in reporting and contributed to the arrest and conviction of two violent clients.

Restorative Justice Conferencing

Given their explicit focus on enhancing legitimacy (Daly et al. 2006) and improving both victims’ and offenders’ perceptions of procedural justice, restorative justice conferencing programs were included in the systematic review of police legitimacy. According to Marshall (1999), p. 5, “Restorative justice is a process whereby parties with a stake in a specific offence collectively resolve how to deal with the aftermath of the offence and its implications for the future.” When interventions are facilitated by police, improved perceptions of police procedural justice can lead to improved perceptions of police legitimacy.

Most empirical research on restorative justice processes has been conducted on those processes that involve a face-to-face meeting between the offender, victim, and supporters. Although conferences can be mediated by either a police officer (the Wagga model: Moore and O’Connell 1994) or a nonpolice officer trained for the purpose (the New Zealand model: Daly et al. 2006), the systematic review focused on the former, more clearly police-led interventions because the police, as conveners, have direct power to enforce the outcomes of the conference (Moore and O’Connell 1994).

The systematic search located a number of articles reporting on studies of police-run restorative justice conferences, as well as restorative cautioning, and a program that trained police officers in mediation skills and gave them the opportunity to refer parties to a local mediation facility during an incident.

The review found that, overall, police-run conferences had a positive impact on process outcomes for both offenders and victims. The policeled conferencing model has also been observed to prompt a shift from a retributive, adversarial policing culture to one focused on restoration and harm prevention (Moore and O’Connell 1994), although this was not observed in all cases. One study measured the effects of restorative justice interventions on perceptions of police legitimacy and found a substantial effect across participants and crime types.

The effect of restorative justice on instrumental outcomes is less clear. While some scholars have found that conferenced offenders had lower recidivism than court-processed offenders, the difference was not large enough to be significant and varied greatly across different types of offence. Others have similarly found that individuals who were cautioned using restorative justice procedures were less likely to reoffend than individuals cautioned using traditional police methods.

Problem-Oriented Policing

Problem-oriented policing strategies fall into Weisburd and Eck’s (2004) top right quadrant of high diversity of approaches/high level of focus on a particular problem (see Fig. 1) and generally fall into the instrumental model of police legitimacy. The systematic search uncovered a diverse range of problem-oriented policing interventions in the context of police legitimacy, including large-scale initiatives focused on violent crime in general, gun violence, youth gun violence, and juvenile curfews. Other interventions included community alarm systems, specialized task forces for drug reduction, concentrated traffic enforcement, crime prevention through environmental design, training for liquor licensees and bar staff to recognize fake identification, grants to enhance gender-based violence prevention efforts, and vehicle safety programs. Several sources described general problem-oriented policing programs, referred to variously as problem-oriented policing, problem-solving policing, and risk-focused policing.

Study authors identified a range of issues with the implementation of problem-oriented policing interventions, including lack of a single responsible managing agency, citizen anxiety about police and social services becoming involved in their personal lives (e.g., community alarm system case), difficulty with sustaining a high level of focus over time, inability of police to fulfill their commitments according to the program, and difficulty enforcing collaboration between police and partner agencies.

The review showed that only a few problem-oriented policing strategies used the process model of legitimacy, as evidenced by a lack of attention to process-related outcomes in the group of interventions. These included community support, citizen perceptions of procedural justice, interagency communication, and job satisfaction.

Instead, problem-oriented policing strategies identified in the review that articulated measures of police legitimacy tended to measure outcomes related to effectiveness. In particular, the studies reported measures that captured the problems the interventions were trying to address. These measures included improving police legitimacy through improving police effectiveness and impact on violent crime, gang crime, homicides, severe road accidents, speed-related accidents, traffic violations, street crime, burglary, arrests of juveniles, self-reported delinquency, reoffending, calls for service, and citizen perceptions of safety.

Hot Spot Policing

Hot spot policing strategies fall into the high focus/low diversity of approaches typology. This type of strategy is generally implemented by police alone in a small geographic area, with the aim of reducing crime and improving police legitimacy through improved effectiveness. The search located only two evaluations of interventions that could be described as hot spot policing aimed at enhancing legitimacy. Both interventions implemented increased enforcement rates and penalties for disorder crimes in a small geographic area. One evaluator commented that the program, while successful in reducing crime, had created a large number of fugitives from the justice system. The other evaluation found that enforcing disorder crimes had no effect on levels of more serious crime (aggravated burglary and robbery) in the target area.

Clearly, a much larger literature exists on the effectiveness of hot spot policing interventions. However, the sufficiently different language and terminology used in the literature around legitimacy policing and the literature around hot spot policing led to the exclusion of most of these types of interventions from the review. Moreover, either the researchers or police have not viewed hot spot policing as the type of intervention that could enhance police legitimacy. This does not mean that hot spot policing cannot be used to enhance perceptions of legitimacy. Rather, the studies are silent on how hot spot policing could be used to enhance legitimacy.

Standard Model Of Policing

The standard model of policing includes interventions that are low in diversity of approaches/ low in focus. Several such strategies were found that authors linked to police legitimacy. Standard model policing interventions tended to focus broadly on instrumental outcomes and police effectiveness, although this varied among interventions.

Specialized Teams

Several studies described police units that had created specialized teams of officers focused on a particular type of crime, including child protection, domestic and family violence, mental health, drug crime, homicide and violent crime, gang crime, disorder crimes, and automatic number plate recognition intercept teams for traffic violations.

Evaluations of specialized teams often commented on the importance of the commitment of individual officers, especially the commitment of senior officers in their support of the specialized team in accessing information and resources. Interventions in which the team consisted of members from multiple agencies sometimes encountered problems in communication. This was largely due to differences in management structures and decision-making styles between police departments and other agencies, leading to a low level of honesty and trust in working relationships within the teams. Other evaluators commented that the goals of national-level programs did not always match the goals of individuals implementing the intervention in the field. One study found that reassigning officers into structured and response teams was confusing for the officers involved due to a lack of clearly stated objectives for the two groups. Another study found that a particular issue for specialized units was the potential for the unit members to legitimize their role by creating and reinforcing myths concerning the problem they were established to address.

Specialized team interventions generally focused on increasing legitimacy through improving instrumental outcomes, although some interventions did report process outcomes. Several evaluations found that specialized teams were positively received by community members, clients, and community leaders. One study found that it increased positive attitudes of police officers toward their jobs.

Evaluations of specialized teams also tended to emphasize instrumental outcomes, with mixed results. For example, a proactive multiagency mental health unit had a substantial impact on the number of arrests and involuntary hospitalizations made in mental health-related calls for service. In geographic areas assigned a specialized homicide and violent crime task force, rates of violent crime and homicide decreased, although the design of the evaluation prevented authors from attributing this effect directly to the intervention. Domestic violence suspects visited by a specialized domestic violence unit had a lower prevalence of reoffending than suspects visited by regular patrol officers, although frequency and severity of reoffending were not affected for suspects who did reoffend. Less positively, one evaluation found a higher rate of reoffending in suspects visited by a special family violence response team, compared to controls. Another evaluation of a crisis intervention team for domestic violence found that the crisis team generated more arrests than regular officers in domestic violence cases but that victim cooperation was lower in cases visited by the specialized team than in other cases.

Targeted Enforcement

Targeted enforcement covers a range of strategies aimed at reducing a particular problem by increasing detection of the problem and enforcement of penalties. Targeted enforcement falls under the standard model of policing and can be separated from problem-oriented policing because of its low diversity of approaches and sole implementation by police agencies, with no collaboration between police and citizens or other agencies. Enforcement strategies tended to target particular crimes such as sales of alcohol and tobacco to minors. One targeted enforcement strategy used enhanced forensic science techniques in investigations.

The systematic search found few evaluations of this type of intervention that articulated to the legitimacy theme. As such, little information was gathered on the process of implementing these interventions. The standard policing interventions generally focused on instrumental outcomes, to the exclusion of process-type outcomes. The evidence for the effectiveness of these strategies was not very positive. For example, in one case in which enhanced forensic science techniques were implemented as a strategy, the researchers found that rates of case closure were no higher than in other cases, and the special forensic science technology was very expensive to use. A strategy targeting tobacco sales to minors found that although targeted communities improved their compliance with tobacco sales laws faster than control communities, adolescents’ self-reported access to, and use of, tobacco was not affected. Another intervention involving undercover police checks of licensed premises failed to produce any significant deterrent effect on future sales of alcohol to minors.

Officer Training

One of the primary sources for improved police legitimacy is citizens’ day-to-day interactions with the police, independent of any large-scale initiative. Police can implement training interventions to increase the likelihood of a positive outcome in officers’ encounters with members of the public. Although evaluations of this type of intervention are rare, Hails and Borum (2003) suggest that internal training to improve legitimacy is carried out by many police forces. Legitimacy training initiatives are distinct from other types of police training focusing on combat or responding to hostile situations. The search discovered several different citizen-focused police training initiatives, including community policing training, diversity training, leadership training, life skills training, crisis intervention training, and victim-focused training.

The overuse of force and arrest against particular sections of society by police (e.g., ethnic minority groups), and the overrepresentation of these populations within the prison population compared to society in general, represents a key weakness of the criminal justice system and a significant challenge to its legitimacy in many countries. Legitimacy training may thus include specific training to help officers respond to the needs of populations they are not familiar with, for example, victims of domestic violence or people with a physical or mental disability. It is hypothesized that specialized training for particular population interactions enables police officers to respond to the needs of these populations in crisis situations, thereby reducing the officers’ need to resort to arrest or force (Hails and Borum 2003).

Implementation issues identified in police training generally focused on the occasional discrepancies between officers’ training and expectations of their performance in the field. For example, a community policing training program evaluation found that although the training was successful in teaching officers about community policing, their ability to implement their training in practice was constrained because of performance indicators that focused on instrumental outcomes, such as arrests and tickets, rather than the process-type outcomes promoted in community policing.

Police training interventions tended to focus on the process model of legitimacy and generally reported positive results for process-type outcomes, particularly those relating to police perceptions. Officers trained in crisis intervention tended to give themselves more positive ratings for handling cases than did officers who did not receive the training. Similarly, command staff who participated in diversity training reported an increased ability to communicate effectively; police who received victim-focused training reported more favorable attitudes and behavioral intentions toward victims than did untrained officers; and officers who underwent training in life skills reported increases in self-confidence and lower dogmatism compared to untrained officers. An exception to the generally positive results was a study evaluating police leadership training which found no effect of the training on police leadership styles.

Officer training programs had mixed impacts on process outcomes regarding citizen perceptions of police. Clients of the crisis intervention training program were happier with the service provided by trained officers than that of untrained officers, but an evaluation of victim-focused training found no effect on victim perceptions of police or fear of crime. Instrumental outcomes were not generally measured by police training interventions. The crisis intervention training program produced a null effect on the rate of return calls to the same address.

Discussion And Conclusion

Police legitimacy is important to maintaining order and ensuring compliance with laws and police requests. If people feel the police have legitimacy, they will voluntarily obey police, freeing police resources from enforcing compliance based on fear of punishment or anticipation of reward. While there are multiple pathways to improving police legitimacy, including improving police performance and enhancing the nature of police–citizen encounters, the focus of this review was on strategies that sought to improve police legitimacy either (1) explicitly (as identified by the authors of papers and reports on the intervention) or (2) implicitly through the use of procedural justice elements in policing.

The systematic review found 163 studies that evaluated policing interventions articulated as approaches seeking to enhance perceptions of police legitimacy, of which 104 studies with sufficient data are used in this essay to show the breadth of research in this area. For the population of 163 studies, text analysis shows that the term “legitimacy” is indeed a key concept within the policing literature. A map of the conceptual structure of the body of police legitimacy evaluation literature revealed that legitimacy was the central underlying concept, with strong links to the concepts of policing and procedural justice. However, while legitimacy was central in the text analysis, it was clearly not an outcome routinely measured or considered to be of primary importance by study authors. Interventions tended to measure effectiveness using process-type outcomes, such as citizens’ perceptions of the fairness of police decisions, or instrumental outcomes, such as citizens’ perceptions of police effectiveness, but rarely did they measure the apparently central concept of legitimacy. Thus, this review concludes that the enthusiasm for police legitimacy as a construct in the theoretical and survey literature is not matched in the evaluation literature.

The preponderance of these 163 legitimacyenhancing police interventions was in the two quadrants that Weisburd and Eck (2004) identify as diversity of approaches, including community- and problem-oriented policing approaches. Community policing types of interventions that sought to enhance legitimacy tended to use the process model of legitimacy, in which citizens’ perceptions of police legitimacy are influenced by their perceptions of the process of policing, rather than police effectiveness. In contrast, problem-oriented policing types of interventions tended to use an instrumental approach to legitimacy, in which increased police effectiveness leads to increased legitimacy.

This overview suggests that while many policing interventions, including community policing, problem-oriented policing, hot spot policing, and standard model policing, may be useful for improving police legitimacy, these approaches are rarely explicitly articulated as legitimacy-enhancing interventions. In theory, previously evaluated interventions may have influenced legitimacy in multiple ways, through improving citizens’ perceptions of police processes or through improving police effectiveness. However, in practice very few evaluations measure legitimacy as an outcome. It is suggested, therefore, that evaluators need to carefully focus on measuring a wider range of outcomes in addition to the more commonly reported process and instrumental outcomes.

Bibliography:

- Bayley DH, Mendelsohn H (1969) Minorities and the police: confrontation in America. Free Press, New York

- Bell J (2004) The police and policing. In: Sarat A (ed) The Blackwell companion to law and society. Blackwell Publishing, Blackwell Reference Online. Retrieved from http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/ tocnode?id¼g9780631228967_chunk_g97806312289 6710

- Bellman A (1935) A police service rating scale. J Crim Law Criminol (1931–1951) 26(1):74–114

- Bennett S, Denning R, Mazerolle L, Stocks B (2009) Procedural justice: a systematic literature search and technical report to the National Policing Improvement Agency. ARC Centre of Excellence in Policing and Security, Brisbane

- Daly K, Hayes H, Marchetti E (2006) New visions of justice. In: Goldsmith A, Israel M, Daly K (eds) Crime and justice: a guide to criminology, 3rd edn. Lawbook Company, Sydney, pp 439–464

- Decker SH (1981) Citizen attitudes toward the police – a review of past findings and suggestions for future policy. J Police Sci Adm 9(1):80–87

- Fielding NG (2002) Theorizing community policing. Brit J Criminol 42(1):147–163

- Hails J, Borum R (2003) Police training and specialized approaches to respond to people with mental illnesses. Crime Delinq 49(1):52–61

- Hinds L, Murphy K (2007) Public satisfaction with police: using procedural justice to improve police legitimacy. Aust N Z J Criminol 40(1):27–42

- Maher L, Dixon D (1999) Policing and public health: law enforcement and harm minimization in a street-level drug market. Br J Criminol 39(4):488–512

- Marshall TF (1999) Restorative justice: an overview. Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate, London

- Mastrofski SD, Snipes JB, Supina AE (1996) Compliance on demand: the public’s response to specific police requests. J Res Crime Delinq 33(3):269–305

- Mazerolle L, Bennett S, Davis J, Manning M (2013) Legitimacy in policing. The Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews. http://campbellcollaboration.org/lib/project/141/

- McCluskey JD (2003) Police requests for compliance: coercive and procedurally just tactics. LFB Scholarly Publishing, New York

- Moore DB, O’Connell T (1994) Family conferencing in Wagga Wagga: a communitarian model of justice. In: Alder C, Wundersitz J (eds) Family conferencing and juvenile justice: the way forward or misplaced optimism? Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra, pp 15–44

- Parratt SD (1938) How effective is a police department? Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 199:153–164

- Reiner R (1985) The politics of the police, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Reiss AJ (1971) The police and the public. Yale University Press, New Haven

- Skolnick JH, Bayley DH (1988) Theme and variation in community policing. Crime Justice 10:1–37

- Sunshine J, Tyler TR (2003) The role of procedural justice for legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law Soc Rev 37(3):513–548

- Thibaut JW, Walker L (1975) Procedural justice: a psychological analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

- Tyler TR (1990) Why people obey the law. Yale University Press, New Haven

- Tyler TR (2003) Procedural justice, legitimacy, and the effective rule of law. Crime Justice 30:283–357

- Tyler TR (2004) Enhancing police legitimacy. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 593:84–99

- Tyler TR (2006) Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annu Rev Psychol 57:375–400

- Tyler TR, Fagan J (2008) Legitimacy and cooperation: why do people help the police fight crime in their communities? Ohio State J Crim Law 6:231–275

- Tyler TR, Huo YJ (2002) Trust in the law. Russell Sage, New York

- Tyler TR, Lind EA (1992) A relational model of authority in groups. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 25:115–191

- Weisburd D, Braga AA (eds) (2006) Police innovation: contrasting perspectives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Weisburd D, Eck JE (2004) What can police do to reduce crime, disorder, and fear? Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 593(1):42–46

- Wells LE (2007) Type of contact and evaluations of police officers: the effects of procedural justice across three types of police–citizen contacts. J Crim Justice 35(6):612–621

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.