This sample Police Selection Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Over the past 30 years, great progress has been made in developing a process for selecting police officers. There are four distinct phases to the selection process: conducting a job analysis, determining which applicants have the competencies to be good officers, investigating the background of the applicant, and conducting a psychological evaluation to determine if there is something about the applicant that would be a threat to the safety of the officer or to others. Each of these four phases is conducted by professionals with very different skills and training. This research paper will describe each of the four phases and summarize the research findings regarding what methods best predict police officer job performance.

Conducting A Job Analysis

The first step in developing a system to hire police officers is to conduct a job analysis. The goal of a job analysis is to identify the tasks that are performed, the conditions under which they are performed, and the competencies needed to perform the tasks. Although there are many job analysis methods, the typical job analysis begins with the job analyst observing the job being performed (ride alongs) and then conducting interviews with incumbents. These interviews are conducted with individual officers, groups of officers at one time, and their supervisors. When the interviews are conducted with groups of incumbents and supervisors, they are called subject-matter expert (SME) conferences.

Once the observations and interviews are concluded, the next step is to develop a task inventory and a competency inventory. The task inventory is a list of the tasks performed by the officers, and the competency inventory is a list of competencies (e.g., knowledge, skills, abilities) needed to perform the tasks. Next to each task are scales where incumbents will rate the frequency with which a task is performed as well as the importance of the task. Some tasks, such as writing traffic citations, will be rated as being important and frequently occurring, whereas others, such as shooting a gun, will be rated as occurring with low frequency but of having high importance.

Once the task and competency inventories have been developed, they are administered to a sample of police officers who will rate the frequency and importance of the tasks and competencies. These ratings are then summarized to determine which tasks and competencies are critical to the performance of the job.

Although the critical tasks identified in the job analysis are often similar across law enforcement agencies, the frequency with which they occur can vary tremendously. That is, while every police officer makes arrests and writes traffic citations, the frequency of those activities might be different in a large city with a high crime rate than it would in a small rural town.

Developing The Test Battery

Now that the critical tasks and competencies have been identified, the next step is to decide how to measure whether an applicant has the necessary competencies to perform the essential tasks. Some competencies, such as knowledge of the law, will be taught in the academy and thus will not be a part of the selection system. For competencies that cannot be easily learned in the academy, it is essential to test for them prior to hiring the officer. Although the term test often conjures up the image of a paper-and-pencil test, psychologists and the courts use the term to describe any technique used to evaluate someone. Thus, selection methods such as interviews and background checks are considered to be tests. Common tests used in police selection include minimum qualifications, interviews, cognitive ability tests, personality inventories, and physical ability tests.

Minimum Qualifications

Every law enforcement agency has minimum qualifications that an applicant must have to even be considered for the job. These minimum qualifications, often determined by state regulation, include such requirements as being 21 years of age, having at least a high school diploma/ GED, possessing a valid driver’s license, and having never been convicted of a felony. As an example, in 2012, the minimum requirements in Arizona are:

- Be a United States citizen

- Be at least 21 years of age; except that a person may attend an academy if the person will be 21 before graduating

- Be a high school graduate or have successfully completed a General Education Development (G.E.D.) examination

- Undergo a complete background investigation

- Undergo a medical examination within 1 year before appointment

- Not have been convicted of a felony or any offense that would be a felony if committed in Arizona

- Not have been dishonorably discharged from the United States Armed Forces

- Not have been previously denied certified status, have certified status revoked, or have current certified status suspended

- Not have illegally sold, produced, cultivated, or transported for sale marijuana

- Not have illegally used marijuana for any purpose within the past 3 years

- Not have ever illegally used marijuana other than for experimentation

- Not have ever illegally used marijuana while employed or appointed as a peace officer

- Not have illegally sold, produced, cultivated, or transported for sale a dangerous drug or narcotic

- Not have illegally used a dangerous drug or narcotic, other than marijuana, for any purpose within the past 7 years

- Not have ever illegally used a dangerous drug or narcotic other than for experimentation

- Not have ever illegally used a dangerous drug or narcotic while employed or appointed as a peace officer

- Not have a pattern of abuse of prescription medication

- Undergo a polygraph examination

- Not have been convicted of or adjudged to have violated traffic regulations governing the movement of vehicles with a frequency within the past 3 years that indicates a disrespect for traffic laws or a disregard for the safety of other persons on the highway

- Read the code of ethics and affirm by signature the person’s understanding of and agreement to abide by the code

Interviews

Interviews used in police selection will differ in structure and style. The structure of an interview is determined by the source of the questions, the extent to which all applicants are asked the same questions, and the structure of the system used to score the answers. A structured interview is one in which (1) the source of the questions is a job analysis (job-related questions), (2) all applicants are asked the same questions, and (3) there is a standardized scoring key to evaluate each answer.

An unstructured interview is one in which interviewers are free to ask anything they want (e.g., Where do you want to be in 5 years? What was the last book you read?), are not required to be consistent in what they ask of each applicant, and may assign numbers of points at their own discretion. Interviews vary in their structure, and rather than calling interviews structured or unstructured, it might make more sense to use terms such as highly structured (all three criteria are met), moderately structured (two criteria are met), slightly structured (one criterion is met), and unstructured (none of the three criteria are met). The research is clear that highly structured interviews are more reliable and valid than interviews with less structure (Huffcutt and Arthur 1994).

The style of an interview is determined by the number of interviewees and number of interviewers. One-on-one interviews involve one interviewer interviewing one applicant. Serial interviews involve a series of single interviews. For example, the lieutenant might interview an applicant at 9:00 a.m., the captain interviews the applicant at 10:00 a.m., and the chief interviews the applicant at 11:00 a.m. Return interviews are similar to serial interviews with the difference being a passing of time between the first and subsequent interview. For example, an applicant might be interviewed by the HR manager and then brought back a week later to interview with the chief. Panel interviews have multiple interviewers asking questions and evaluating answers of the same applicant at the same time. Panel interviews are the most commonly used interviews in police selection.

Questions asked in job interviews for law enforcement positions often focus on two major areas: the applicant’s background and their situational judgment. Background questions might focus on whether the applicant has used illegal drugs, why they want to be a police officer, and the extent to which they have engaged in violent behavior (e.g., fights at school, yelling at a girl/ boyfriend). Situational judgment questions ask the applicant how he or she would handle a hypothetical situation. For example, an applicant might be asked, If you saw a fellow officer accept a bribe, what would you do? or If a motorist would not roll down their window during a traffic stop, what would you do?

Interview questions often vary tremendously across law enforcement agencies. For example, questions asked of applicants for the Michigan State Police focus on building trust, adaptability, decision making, work standards, initiating action, stress tolerance, continuous learning, customer focus, communication, and job fit, whereas questions asked in one New Mexico agency covered such topics as history, current events, and hobbies.

Cognitive Ability Tests

In one form or another, cognitive ability tests are commonly used in law enforcement selection. This category of tests includes a wide variety of tests ranging from those tapping general intelligence to those tapping such specific aspects of cognitive ability as reading, math, vocabulary, and logic. From a content validity perspective, cognitive ability tests are thought to be important in law enforcement selection as they are related to the ability to perform such tasks as learning and understanding new information, writing reports, making mathematical calculations during investigations, and solving problems.

Cognitive ability tests can be placed into four categories on the basis of where they were developed and the extent to which they are commercially available: Publisher developed general cognitive ability tests, nationally developed law enforcement tests, tests developed by the federal government, and locally developed civil service exams.

Publisher Developed General Cognitive Ability Tests. This first category includes cognitive ability tests developed by national test publishers. These tests are available for a wide variety of uses and can be purchased directly from the publishers. Though these tests were not specifically designed for law enforcement selection, many are certainly compatible with constructs related to law enforcement performance. Tests from this category that are commonly used in law enforcement selection include the Wonderlic Personnel Test, Nelson-Denny Reading Test, Shipley Institute of Living Scale, and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

Nationally Developed Law Enforcement Tests. The second category of cognitive ability tests includes those developed by consultants or trade organizations for specific use with law enforcement agencies. Examples of tests from this category include the Entry-Level Police Officer Test, National Police Officer Selection Test (POST), and the Law Enforcement Candidate Record (LECR). The Entry-Level Police Officer Test, published by the International Public Management Association for Human Resources (a trade organization), is a 100-item test that measures observation and memory, ability to learn police material, verbal and reading comprehension, and situational judgment and problem solving. It also contains a noncognitive component that measures interest in policing as a career. In contrast, the POST, published by Stanard and Associates (a private company), is a 75-item test that measures arithmetic, reading comprehension, grammar, and incident report writing.

Tests Developed by the Federal Government. The third category of tests was developed by the federal government for use either with the military or with general employment testing. The major test in this category used in law enforcement selection was the Army General Classification Test. Although these tests were commonly used for police selection in the 1960s and 1970s, they are seldom used today outside of the federal government.

Locally Developed Civil Service Exams. The fourth category consists of cognitive ability tests developed by various municipalities and Civil Service Commissions for their own use. Normally, the municipality hires an outside consulting firm to develop these tests. Though it is not unusual for these tests to be shared with other agencies, they are not commercially available.

The use of cognitive ability tests in law enforcement selection is controversial. Proponents of these tests cite an abundance of research demonstrating that cognitive ability tests are excellent predictors of performance in a wide variety of jobs (Schmidt and Hunter 1998) as well as good predictors of how a police cadet will perform in the academy (Aamodt 2004). Opponents argue that cognitive ability tests result in adverse impact against Blacks and Hispanics (Roth et al. 2001) and that there are alternative methods with comparable validity but result in lower levels of adverse impact.

Because of the high levels of adverse impact that occur with cognitive ability tests, it is essential that a law enforcement agency conducts a validation study to ensure that the people who score highly on these tests actually perform better on the job than those that do not. In the typical validation study, the test is administered to newly hired police officers, and their scores are correlated with such criteria as academy grades, supervisor ratings of on-the-job performance, number of commendations received, and number of disciplinary incidents.

In recent years, applicants have challenged the legality of cognitive ability tests based on the score needed to pass the test. That is, should the applicants with the highest scores always be given preference over people with lower scores or should the law enforcement agency set a passing score (e.g., 70 %) such that anyone who achieves that score is considered equally qualified for the job? Most law enforcement agencies have adopted the passing score approach.

Personality Inventories

Personality inventories are commonly used methods to predict performance in law enforcement settings (Weiss 2010). Although there are hundreds of personality inventories available, they generally fall into one of two categories based on their intended purpose: measures of psychopathology and measures of normal personality.

Measures of Psychopathology. Measures of psychopathology (abnormal behavior) determine if individuals have serious psychological problems such as depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Commonly used measures of psychopathology used in law enforcement research include the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2 (MMPI; MMPI-2), Millon Multiaxial Clinical Inventory (MMCI-III), Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI), and the Clinical Assessment Questionnaire (CAQ). Such measures are designed to screen out applicants who have psychological problems that would cause performance or discipline problems on the job. Measures of psychopathology are not designed to select in applicants and are seldom predictive of job performance (Aamodt 2004, 2010).

Measures of psychopathology are considered to be medical exams. As a result, to be in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), they can only be administered after a conditional offer of employment has been made. Prior to the passage of the ADA in 1990, these tests were routinely administered to all applicants.

Measures of Normal Personality. Tests of normal personality measure the traits exhibited by normal individuals in everyday life. Examples of such traits are extraversion, shyness, assertiveness, and friendliness. Though there is some disagreement, psychologists today generally agree there are five main personality dimensions. Popularly known as the Big Five, these dimensions are openness to experience (bright, adaptable, inquisitive), conscientiousness (reliable, dependable, rule oriented), extraversion (outgoing, friendly, talkative), agreeableness (works well with others, loyal), and emotional stability (calm, not anxious or tense). Commonly used measures of normal personality in law enforcement selection include the California Psychological Inventory (CPI), M-PULSE, 16PF, NEO PR-R, Inwald Personality Inventory (IPI), and Edwards Personal Preference Schedule (EPPS). In contrast to measures of psychopathology, measures of normal personality are used to select in rather than screen out applicants.

Though personality inventories are commonly used in police selection, in part because racial groups tend to score similarly (Foldes et al. 2008), a meta-analysis of the validity of personality inventories indicates that, in general, they are not good predictors of police performance (Aamodt 2004, 2010).

Physical Ability Tests

Most law enforcement agencies require applicants to pass a physical ability test either prior to hire or at the completion of the academy. These physical ability tests usually come in one of two formats. In the first format, applicants perform a variety of exercises related to stamina and strength. Such exercises often include sprints, push-ups, and sit-ups. In the second format, applicants perform a job-related simulation involving physical agility. Such a simulation might involve getting out of a car, running a short distance, leaping over an obstacle, climbing a fence, going through a window, and dry firing a pistol at the end of the obstacle course.

Because physical ability tests often result in adverse impact against women, it is essential that law enforcement agencies establish the validity of their physical ability tests. Best practices include using simulations rather than individual tests (e.g., push-ups) and using cutoff scores that are realistic and appropriate for the work being performed.

Below is an example of the physical ability test used by the Oakland (CA) Police Department:

- Cone Maze: While running through the cone maze, you may not knock over or move any of the cones from its original position. If you do, you will be asked to put the cone back to its original position. The additional time you use to do so will be counted toward your overall qualifying time.

- Fence Climb: You will have three (3) chances to climb over the 5-ft fence. If you fail to go over the fence after three attempts, the proctor will stop the test and give you a failing grade. While climbing the fence, you may not use the support on either side of the fence to assist you.

- Ditch Jump: You will have three (3) chances to jump over the simulated 4-ft ditch (rubber mats). Your foot must not come in contact with the ditch area at anytime. If you fail to complete this event after three attempts, the proctor will stop the test and give you a failing grade.

- Stair Climb/Window Entry: When climbing the stairs and going through the window, you must step on each stair on both the front and backside of the simulated window frame. You may use any part of the window frame to brace yourself in order to help facilitate your climb through the window frame.

- Dummy Drag: In order to pass this event, you must successfully drag the dummy around the designated cone and drop it after it crosses over the black tape marker. Then you will run as quickly as you can to the handcuff simulator platform. Your timed run will end when you touch the handcuff simulation platform.

- Handcuffing Simulator: This is the last event of the physical ability test. You are allowed three (3) attempts to complete. You must grasp each end of the bar and bend the bar until both ends touch. You must hold the bar in this position for 30 s. You may not interlock your fingers and your hands must not touch your chest at any time. If you let the ends of the bar separate, even slightly, your time will be restarted and you must begin the event again. Remember: The time begins when the ends of the bar touch.

The applicant must complete the first five events within 2 min and 35 s. To pass the handcuff simulation, the applicant must perform the activity for 30 s while maintaining a proper posture.

Background Investigation

Once it has been determined that an applicant has the competencies needed to be an effective police officer, the department then conducts a background investigation to determine if there are problems that were missed in the interview and testing process. The background investigation begins with the applicants completing a lengthy set of questions regarding their education, work history, credit history, driving record, arrest and conviction record, and previous places of residence. The department will then verify whether the applicants have the degrees they claim to have earned, worked at the jobs listed in their application, and listed all arrests or convictions. From there, the investigators will often contact the applicants’ former professors, employers, and neighbors to determine if the applicant acted in a way that would reflect potential problems. For example, an employer might indicate that an applicant was verbally aggressive with customers, a neighbor might mention the loud music and noise from wild parties that came from the applicant’s apartment, and a professor might indicate that the applicant occasionally seemed stoned during her 9:00 a.m. class. The last step in the background investigation is a polygraph test in which the applicant is asked questions about such activities as drug use, theft, and aggressive acts.

At the conclusion of the background investigation, the investigator will compile all of the information and make a recommendation about the fitness of the applicant. This overall recommendation is important because seldom does a single piece of information (e.g., number of traffic citations, being fired from one job) predict how an officer will perform on the job. Instead, it is a pattern of problematic behaviors that is most predictive of potential problems.

Psychological And Medical Evaluation

The final step in the selection process is for the applicant to be evaluated by a licensed physician and a licensed psychologist. The physician is given a job description and asked to evaluate whether the applicant has any medical condition that would keep him or her from performing the duties of a police officer. The clinical psychologist is asked to determine if the applicant has a psychological disorder that might make them a potential danger to themselves or to others. The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that the medical exam and the psychological exam be administered after a conditional offer of hire. That is, the applicants are told that they will be hired as long as they pass the medical and psychological evaluations.

The nature of the psychological exam will depend on the needs of the department. If the department already has a comprehensive selection system such as that described in this research paper, the role of the psychological exam is limited to determining whether the applicant has some sort of psychopathology that will limit his or her ability to be an effective police officer. This limited role is because the law enforcement agency has already tested and interviewed the applicant and believes that the applicant has the competencies needed to perform the job. What the agency needs from the psychologist is certification that there is not some form of psychopathology that will make the applicant a danger to themselves or to others.

If, however, the applicant has applied to a small police department that does not use extensive testing, the agency might ask the psychologist to determine not only whether the applicant has some form of psychopathology but also whether the applicant has the basic competencies (e.g., personality, cognitive ability) to effectively perform the job. In some states, such as New Mexico, an applicant can go directly to a clinical psychologist to get certified and then take that certification to the department as proof that they are ready to be hired and sent to the academy.

Though clinical psychologists will differ in how they conduct psychological evaluations, there are usually three main parts to the evaluation: assessment of background information, a written test of psychopathology (e.g., MMPI-2), and a clinical interview. The clinician will use all three components to arrive at an overall recommendation of whether the applicant is psychologically fit to be a law enforcement officer.

From these assessments, Trompetter (1998) believes that the clinical psychologist should determine whether the applicant:

- Can accept criticism

- Can adapt to change

- Be assertive when appropriate

- Be interpersonally sensitive

- Is motivated to achieve

- Be objective

- Be persuasive

- Be vigilant

- Can conform to rules and regulations

- Has good impulse control

- Demonstrates integrity

- Demonstrates practical intelligence

- Demonstrates reliability

- Demonstrates social concern

- Exhibits a positive attitude

- Can manage his/her anger

- Can tolerate stress

- Can work in a team

The Academy

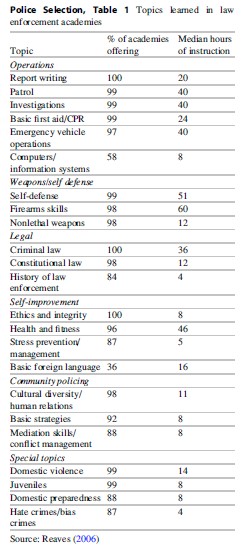

Once the applicant has been hired, he/she will still need to complete a law enforcement academy to become certified as a police officer, sheriff’s deputy, state trooper, or other law enforcement professional. Graduation from an accredited academy is mandatory in order to be certified as a peace officer. Each state sets a minimum number of training hours for an academy, but each academy can offer more extended training. The average academy lasts 761 h (19 weeks) at a cost per cadet to complete the academy of $16,100(Reaves 2006). Louisiana has the fewest required hours (520), and West Virginia has the most (1,582; Rojek et al. 2007). Approximately 14 % of cadets who enter the academy fail to complete the requirements needed to become a certified police officer (Reaves 2006). As shown in Table 1, there are a wide range of topics studied in the typical academy.

After completing the academy, the final step toward becoming a law enforcement professional is to complete supervised field training. Some academies include this field training as part of the academy training, whereas others have the agency that hired the cadet conduct the training. The typical department requires 520 h (13 weeks) of field training (Rojek et al. 2007).

Conclusion

As you can see from this research paper, law enforcement agencies often expend tremendous effort and finances to ensure that their agencies are staffed with high-quality employees. To survive a legal challenge, each stage of the selection process must be shown to be job related.

Bibliography:

- Aamodt MG (2004) Research in law enforcement selection. BrownWalker, Boca Raton

- Aamodt MG (2010) Predicting law enforcement officer performance with personality inventories. In: Weiss PA (ed) Personality assessment in police psychology. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield

- Foldes HJ, Duehr EE, Ones DS (2008) Group differences in personality: meta-analyses comparing five U.S. racial groups. Pers Psychol 61(3):579–616

- Huffcutt AI, Arthur W (1994) Hunter and Hunter (1984) revisited: interview validity for entry-level jobs. J Appl Psychol 79(2):184–190

- Reaves BA (2006) State and local law enforcement training academies, 2006. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

- Rojek J, Kaminski RJ, Smith MR, Scheer C (2007) South Carolina law enforcement training survey: a national and state analysis. University of South Carolina, Columbia

- Roth PL, BeVier CA, Bobko P, Switzer FS, Tyler P (2001) Ethnic group differences in cognitive ability in employment and educational settings: a meta-analysis. Pers Psychol 54(2):297–330

- Schmidt FL, Hunter JE (1998) The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings. Psychol Bull 124(2):262–274

- Trompetter P (1998) Fitness-for-duty evaluations: what agencies can expect. Police Chief 60:97–105

- Weiss PA (2010) Personality assessment in police psychology. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.