This sample Race and the Likelihood of Arrest Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Opinion surveys in the United States often report that citizens believe that race influences how police officers treat the public. This research paper summarizes a recent meta-analysis by Kochel et al. (2011) that examined the existing empirical evidence on the relationship between race and a police officer’s decision to make an arrest. The findings support the conclusion that black suspects are more likely to be arrested than white suspects when encountering a police officer. This effect does not appear to be the result of various alternative hypotheses, such as the demeanor of the suspect or other observable legal and extralegal factors. Although the research consistently supported a racial bias hypothesis, the strength of the effect across studies did vary. Additional research is needed to better understand the factors that influence this relationship.

Background

Harvard University Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., was arrested for disorderly conduct in July of 2009 (Cambridge Review Committee 2010). Police arrived at his home in response to a call from a neighbor reporting a possible break-in. In fact, Professor Gates and a friend had forcibly opened a stuck door. When the police arrived, Professor Gates was already in his home. The police report indicated that in the course of questioning professor Gates, he acted inappropriately toward an officer who had requested identification from the professor and had asked him to step outside. The professor claimed that he was treated inappropriately and that it was due to his race. The officer claimed otherwise.

Professor Gates’ perception that he was treated unfairly by the police is a common perception among blacks in the United States. Perceptions of racial bias on the part of the police are strongly related to race and ethnicity. A 2002 survey of the general public by Weitzer and Tuch (2005) showed that 75 % of blacks and 54 % of Hispanics believe that local police treat minorities worse than whites. This is in stark contrast to the roughly 76 % of whites who think that the police treat whites and minorities equally. Personal experiences with the police also differ substantially between racial and ethnic groups. Based on this survey, 37 % of blacks, 23 % of Hispanics, and 1 % of whites reported that they believe they were treated unfairly by the police because of their race or ethnicity. Professor Gates’ perception that he was treated unfairly by the police is a common perception among blacks in the United States.

A fundamental question raised by the Gates case and the public opinion surveys is whether this perception of racially biased treatment by the police accurately reflects police behavior. Police agencies and the general public should be concerned that a high percentage of minorities believe that they are being treated unfairly by the police. This undermines police legitimacy and reinforces racial tensions. However, an important issue is whether this perception of racially biased treatment by the police accurately reflects police behavior.

The research challenge is that in the absence of overt racist behavior, such as a racial epithet, it is difficult to know whether race played a role in an individual case, such as that of Professor Gates. To address this problem, social scientists have compared the arrest rates for white and black suspects under similar circumstances from a large number of police–citizen encounters (Although the treatment of other racial and ethnic minority groups is matter of concern, most studies focus on the comparison of whites and blacks). The credibility of such results rests on how well the research established the “under similar circumstances” comparison. The goal is to ensure that an observed difference in arrest rates between a white and black citizen is not the result of different levels of evidence, criminal behavior, or other issues that might be confounded with race. Numerous studies of this type have been conducted over the past several decades. Prior reviews of these studies, including a blue-ribbon academic panel, judged the findings to be so mixed that they have been unable to draw a definitive conclusion. The National Research Council’s Committee to Review Research on Police Policy and Practices concluded that “the evidence is mixed, ranging from findings that indicate bias against racial minorities, findings of bias in favor of racial minorities, and findings of no race effect” (Skogan and Frydl 2004, pp. 122–123). Similarly, a working group of 45 social scientists formed by the American Sociological Association also was unable to draw a firm conclusion on this issue (Rosich 2007). Both of these groups relied on traditional narrative review methods and both called for additional research to better understand whether and under what circumstances police behave in a racially biased manner.

More recently, Kochel et al. (2011) published a meta-analysis of these studies. Meta-analysis is a useful tool for assessing the strength and consistency of evidence regarding a hypothesis, such as the effect of race on arrest, across multiple studies. It has also proven to be useful in areas where narrative reviews arrive at equivocal conclusions. Kochel and colleagues’ meta-analysis concluded that the evidence does support the contention that the police are more likely to arrest a minority than a white suspect under similar circumstances. The methods and findings of this meta-analysis are summarized below, followed by a discussion of key issues and controversies related to this issue.

Meta-Analysis Of Race And Arrest

Summary Of Methodology

The sample of studies included in the Kochel and colleagues’ (2011) meta-analysis was comprised of observational studies of police–citizen encounters that examined the relationship between a citizen’s race/ethnicity and arrest. To be included, these studies must have collected data at the level of individual suspects/encounters and measured arrest (versus a less severe alternative) and the suspect’s race/ethnicity. There were several research designs that met these criteria. The two most common were field studies where researchers observed and recorded extensive data on police–citizen interactions and existing records generated by police officers, the majority of which were data routinely collected as part of police incident reports or vehicle and pedestrian stops. Also included were a survey of crime victims and a study based on data extracted from juvenile referral records.

Kochel and colleagues developed and implemented a systematic search strategy designed to identify all available studies that met the inclusion criteria for the review. This review was restricted to studies conducted within the United States, so the results cannot be generalized to other countries. To minimize publication-selection bias, both published and unpublished studies were sought and included. This process identified 40 documents that reported the results of 23 distinct research projects and 27 independent data-sets. Information was coded from these studies that reflected each study’s method of data collection, sampling strategy, sample size, geographic location and years of data collection, crime type, age and sex of the samples, the data source, document type, type of statistical analyses applied, independent variables included in statistical models, and finally the statistical effect size(s) for the relationship of race on arrest.

The effect size for this meta-analysis was the odds ratio. The odds ratio is an index that compares the odds of an arrest for one group (blacks or minorities) with the odds of an arrest for another group (whites). As such, an odds ratio of 1 indicates no difference between the two groups. These odds ratios were coded so that values greater than 1 indicated bias against minorities and values less than 1 indicated bias against whites.

All of these odds ratios were based on statistical models that included additional variables that might influence police arrest discretion, such as the severity of the crime or the demeanor of the offender. As such, these odds ratios were all adjusted for observed features of the encounter, most commonly using logistic regression. A few studies relied on probit regression models or ordinary least squares models. Findings from these models were converted into odds ratios that were directly comparable to those being calculated from the logistic regression models.

Summary Of Results

Kochel and colleagues coded 120 odds ratios across the 27 independent data-sets that reflected a contrast between white and black or minority suspects. When the contrast was between white and minority suspects, the minority sample was predominantly black. Thus, these results focus on the white versus black difference in likelihood of an arrest.

The multiple odds ratios from a single data-set reflected variations in the statistical models estimated on the data. This occurred both within a single publication and across publications based on a common data-set. These different models typically varied the set of independent variables included. These multiple odds ratios from a single data-set do not provide statistically independent information on the direction and magnitude of any race–arrest relationship. To address this, Kochel and colleagues restricted any given analysis to a single odds ratio per independent data-set. Thus, no analysis could include more than 27 odds ratios.

To ensure that results were not overly influenced by the specific odds ratio selected from a given data-set, Kochel and colleagues performed several analyses with different selection rules. These included calculating the average odds ratio for each data-set, selecting the smallest odds ratio for each, selecting the largest odds ratio for each, and selecting the odds ratio that met explicit criteria that they believed represent the best (most accurate) effect size for each. The selection criteria for the best effect size within a data-set gave preference to odds ratios that: (1) were based on a logistic regression model rather than an OLS or probit regression model; (2) had a standard error that was reported directly and not imputed from other information, such as sample size; (3) were based on the full sample, rather than a subset; (4) were from models where the operationalization of the dependent variable was clearly arrests versus no arrest, rather than some other less severe alternative sanction; (5) had a race variable that represented black versus white, rather than minority versus nonminority or white versus nonwhite; (6) were based on a statistical model that included demeanor as an independent variable, (7) were based on a statistical model that included officer characteristics, and (8) were based on a model with the largest number of independent (control) variables.

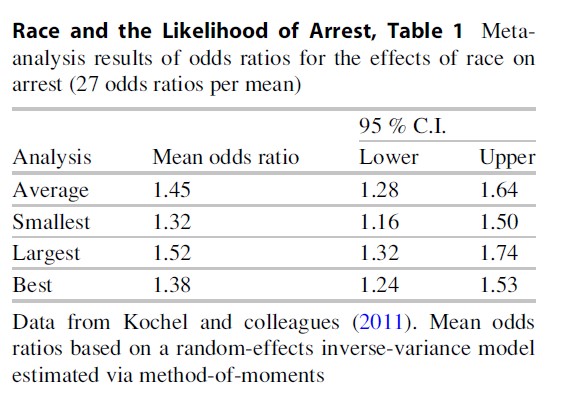

Table 1 presents the meta-analytic mean for these four sets of odds ratios. The meta-analytic method used was the random-effects inversevariance weight approach. This is a conservative approach to meta-analysis and explicitly assumes meaningful variation across studies in the estimate of the race–arrest relationship.

Each of the four methods of selecting one odds ratio per data-set produced an overall mean effect size that was statistically significant. The range in the mean odds ratio across these four sets was 1.32 for the smallest odds ratio per data-set and 1.52 for the largest odds ratio per data-set. Using the average and best odds ratio within each data-set produced very similar results (1.45 and 1.38, respectively). These results suggest that minorities have a higher odds of arrest than nonminorities in a police–citizen encounter. The different selection models showed that the results were robust to which effect size is selected from each data-set.

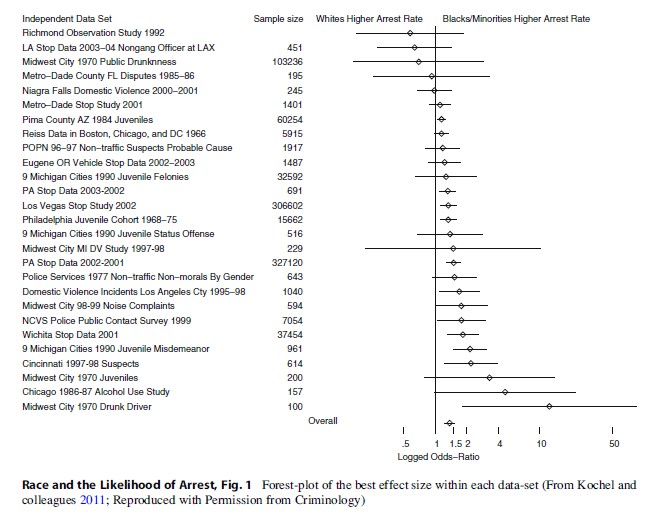

Figure 1 presents a forest-plot for the distribution of odds ratios for the set of effect sizes designated as the best from each data-set. Figure 1 shows that only 4 of the 27 odds ratios were in the negative direction with blacks or minorities having a lower odds of arrest. This would be expected by chance. What is of greater interest is the pattern of results across studies and this pattern supports the hypotheses that race affects the likelihood of arrest.

By conventional standards, these effects are small. To interpret the magnitude of the effect in meaningful terms, Kochel and colleagues converted the overall mean odds ratio of 1.38 (model based on the best effect size within each data-set) into the probability of arrest for minorities and blacks relative to whites. This conversion is based on an assumed arrest rate of 20 % for whites, roughly the average across all samples. Using this value as the benchmark, an odds ratio of 1.38 is equivalent to an arrest probability of 0.26 for minorities and blacks and 0.20 for whites. This is a difference that is large enough to be of practical concern.

Focusing solely on the mean ignores the variability in results across studies. This variability exceeded what would be expected from sampling error alone. Thus, there are true differences in the effect of race on the likelihood of arrest across these studies. Some studies show a stronger race effect than others. Kochel and colleagues performed a series of moderator analyses to explore this variability. These analyses examined both methodological and theoretical explanations for differences across studies.

An important methodological consideration is how the data were collected. Three basic approaches were used across the studies reviewed. The method least susceptible to bias is the use of trained field researchers accompanying police out in the community and coding extensive information about each police–citizen encounter. However, an officer may be affected by the observer’s presence, altering what they do. There is some evidence to suggest that officers are less passive and more legalistic in the presence of an observer (Mastrofski and Parks 1990; Mastrofski et al. 2010; Spano 2007). This may reduce the likelihood of finding a race–arrest relationship. This was the method used for 10 of the 27 data-set. Police officer’s documentation of encounters with citizens was the data source for another 16 data-sets. This method is arguably likely to underestimate any racial bias, as officers would want to present their behavior in a positive light, given strong disincentives in most police agencies toward overt racially biased behavior. A single data-set was based on surveys of victims. As reported by Kochel and colleagues, although the victim survey produced a larger odds ratio (1.79), the officer reported and field researcher data produced highly similar means (1.39 and 1.36, respectively). The differences across these means were not statistically significant and the overall finding of a positive race–arrest relationship is clearly not being driven by a single method.

These studies also differed on the statistical methods used. Once again focusing on the best estimate per data-set, most models were estimated using logistic regression methods (23 of 27), two used probit methods, and two used ordinary least squares methods. The mean for the probit models was highest and the mean for the OLS models was lowest, although not by enough to account for a significant amount of variability in the odds ratios.

Theoretically, several variables may moderate the race–arrest relationship. In considering these variables, scholars have distinguished between disparity and discrimination. The logic is that disparate experiences by race when explained away by legal factors present during the encounter are not discriminatory (Skogan and Frydl 2004, p. 124). Therefore, differential rates of arrest for minorities and whites that dissipate when accounting for legally relevant factors indicate a disparity but not discrimination. Legally relevant factors would include the seriousness of the offense, amount of evidence against the suspect, the presence of a victim supportive of arrest, the presence of a witness on the scene, the suspect being under the influence of drugs or alcohol, or the discovery of additional criminal acts during the course of the officer–citizen interaction.

Kochel and colleagues examined the disparity versus discrimination issue by comparing odds ratios based on statistical models that either did or did not include each of the above legally relevant factors. The differences were trivial, statistically nonsignificant, and failed to explain the positive race–arrest relationship. That is, adjusting for legally relevant disparity did not attenuate the overall finding of discrimination against blacks.

It is possible that individually, these legal factors contribute little to explaining the race–arrest relationship but collectively they might. Kochel and colleagues examined this by assessing the relationship between the number of these factors included in a model and the size of the race–arrest effect using a meta-analytic regression model. The analysis showed that as more legally relevant factors were controlled, the odds ratio became smaller. However, this effect was very small and statistically nonsignificant. The race–arrest relationship remained even for those models with the highest level of statistical control for legally relevant factors.

The suspect’s demeanor was an important extralegal factor that has been examined by roughly half of the studies included in the Kochel and colleagues review. Research supports the idea that a suspect’s demeanor affects the arrest decision. It is important to note that some disrespectful behavior is illegal, such as physical resistance, and as such is legally relevant to an arrest decision.

Other disrespectful behavior is generally not, such as using disrespectful language, and should not be considered by an officer in the arrest decision. What may appear as racial discrimination may be more appropriately attributed to suspect demeanor if demeanor and race are confounded. That is, an officer making a decision to arrest may not be reacting to a suspect’s race but rather to his or her disrespectful behavior. This hypothesis is not supported by the existing data. Statistical models that adjusted for demeanor produced effect sizes roughly comparable to models that did not. Thus, controlling for the demeanor of the suspect did not attenuate the race–arrest relationship.

Key Issues And Controversies

It remains possible that unaccounted for legal and extralegal aspects of the police–citizen encounter could explain the race–arrest relationship, reducing the odds ratio to zero. This is a challenge with all observational research. It is impossible to know if all possible confounds have been accounted for. However, the most likely culprits have been addressed in the literature on this topic, thus increasing the confidence that can be placed in the conclusion that race plays a role, possibly unintentionally, in the arrest decision.

An important hypothesis in this literature has been that the observed race effect is a function of differential demeanor between white and black suspects when encountering a police officer. Research does indicate that police are affected by the demeanor of a suspect in their arrest decision. If on average, the demeanor of black suspects is more hostile than white suspects, then this would produce a differential arrest rate between the two groups. As discussed above, the evidence reviewed by Kochel and colleagues does not support this hypothesis. Other plausible confounds, such of severity of the offense, also failed to explain away the race–arrest relationship.

The robustness of the finding of racial bias to plausible alternative explanations should not obscure the variability in findings across the studies included in the Kochel and colleagues’ meta-analysis. Clearly this effect varies. The meta-analysis did not identify any explanations for this variability but the authors did theorize about possible ecological factors that might be explored in future studies (Klinger 2004). Four possibilities were discussed. The first has to do with the character of the organization, such as how actively the organization attended to unequal treatment of citizens according to their race or the degree of professionalism and bureaucracy of the police agency. Second is the context of who benefits or is served by an arrest. A police officer’s decision to make an arrest may be affected as much by who benefits (e.g., the race or other characteristics of a victim) as who suffers. Third, the neighborhood context may affect an officer’s discretionary judgment regarding an arrest. Police may exert their authority in more racially differentiated ways in some neighborhoods than others. And finally, differences in the race–arrest relationship may reflect the level of political power of a given minority group within a police jurisdiction. Little is known about the role of these ecological factors on police decision making.

Conclusion

In summary, the existing evidence supports the conclusion that blacks have a higher likelihood of arrest than do whites. The research does not demonstrate the causes of this racial disparity, nor does it point to a clear policy response for dealing with it. What it does establish is that where there is smoke there is indeed fire regarding racial disparity in the arrest practices of American police. This certainly shows that further efforts to delineate the legal and ethical implications of racially differentiated policing are based on a solid empirical foundation. Future empirical research should move beyond just testing for a race effect and examine what accounts for variation in this relationship and the effect of any policies designed to reduce it.

Bibliography:

- Cambridge Review Committee (2010) Missed opportunities, shared responsibilities: final report of the Cambridge Review Committee. http://www. cambridgema.gov/

- Klinger DA (2004) Environment and organization: reviving a perspective on the police. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 593:119–136

- Kochel TR, Wilson DB, Mastrofski SD (2011) Effect of suspect race on officers’ arrest decisions. Criminology 49:473–512

- Mastrofski SD, Parks RB (1990) Improving observational studies of police. Criminology 28:475–496

- Mastrofski SD, Parks RB, McCluskey JD (2010) Systematic social observation in criminology. In: Piquero A, Weisburd D (eds) Handbook of quantitative criminology. Springer, New York

- Rosich KJ (2007) Race, ethnicity, and the criminal justice system. American Sociological Association, Washington, DC. http://asanet.org

- Skogan W, Kathleen F (eds) (2004) Fairness and effectiveness in policing: the evidence. National Research Council, Washington, DC

- Spano R (2007) How does reactivity affect police behavior? Describing and quantifying the impact of reactivity as behavioral change in a large-scale observational study of police. J Crim Justice 35:453–465

- Weitzer R, Tuch SA (2005) Determinants of public satisfaction with the police. Police Quart 8:279–297

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.