This sample Randomized Experiments in Criminal Justice Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Randomized experiments are a type of experimental design that uses random assignment to gain equivalence between groups in a study. They are used most often to evaluate the impact of interventions on outcomes. This research paper summarizes the rationale for a randomized experiment, provides the essential components of the design and an example from the policing literature, and briskly highlights its history and status as the “gold standard” for evaluation research. The paper concludes with a description of barriers to experiments and some of the problems in the field that threaten the design.

Background

Experimental research attempts to show a causal relationship of an independent variable (e.g., higher levels of patrol) on a dependent variable (e.g., arrest rates). In experimental research, the researcher uses various methodological approaches to control for the observed and unobserved factors that may influence the dependent variable. The major goal of experimental research is to strengthen internal validity, that is, ensuring that the observed impact is explicitly related to the changes in the independent variable (i.e., treatment condition). There are a wide variety of competing methods in experimental research used to strengthen internal validity, but randomized experiments are considered by many researchers to be the “gold standard.”

A randomized experiment is a type of design that uses random allocation of participants or other units of analysis in order to gain equivalence between subjects or units studied. Although randomized experiments may be used to test theoretical questions, they are most often used in criminal justice to evaluate the impact of interventions, programs, or policies. Randomized experiments that take place in the field, as is often the case in criminal justice, are also referred to as randomized field trials. They are also referred to as randomized control trials (RCT), true experiments, or randomized field experiments.

Although several quasi-experimental approaches are gaining popularity in the social sciences, including criminology (e.g., propensity score matching, regression discontinuity), there is consensus that randomized experiments are optimal for drawing causal inferences between independent and dependent variables. Randomized experiments, when implemented with good fidelity, permit researchers to explain observed findings as a result of the treatment or intervention, ruling out confounding factors that may explain findings.

Internal Validity

To better understand the strength of randomized experiments, a discussion of internal validity is warranted. A research design in which the impact of the intervention can be clearly distinguished from other observed factors is known as having high internal validity. If there are confounding factors involved in the impact of the intervention, then the experiment is considered as having low internal validity. Shadish et al. (2002), among others, have identified the most common threats to internal validity:

- Selection: the preexisting differences between treatment and control subject or units.

- History: an external event occurring at the same time of the study that may influence impact.

- Maturation: changes in subjects or units between measurements of the dependent variable. These changes may be of natural evolution (e.g., aging) or due to time-specific incidences (e.g., fatigue, illness).

- Testing: measurement at pretest impacts measurement at posttest.

- Instrumentation: changes to the instrument or method of measurement in posttest measures.

- Regression to the mean: Natural trends may cause extreme subjects or units who score extremely high or low during the pretest to score closer to the mean at posttest.

- Differential attrition: the differential loss of subjects or units from the treatment group compared to the control group.

- Causal order: the certainty that the intervention did in fact precede the outcome of interest (Farrington and Welsh 2005).

To further illustrate the importance of internal validity, let us suppose a researcher is interested in evaluating the impact of a youth court on a juvenile recidivism. The internal validity is considered high, if at the end of the evaluation, the researcher can show that the change in juvenile recidivism among the intervention groups is due only to the intervention (i.e., youth court) and no other confounding factors were at play. The researcher must show through either research design or analytical procedures that all confounding factors are accounted for in the measurement of outcomes. If the researcher is unable to account for other factors such as seriousness of first offense or the maturation of the study population, he or she must note that the observed effects may be due to other factors. If few threats to validity (or potential confounding factors) are not accounted for, the internal validity of the study would be considered low.

Generally speaking, a randomized experiment has the highest possible internal validity, because this approach allows the researcher to assume that other confounding causes of the outcome of interest, known and unknown, are not systematically influencing the study results. High internal validity in randomized experiments is gained through the process of randomly allocating the treatment or intervention to the experimental and control or comparison groups. Through random assignment, the researcher is not just randomizing the treatment. He or she is randomizing all other factors that may influence the outcome of the treatment. Thus, there is no systematic bias that increases the odds of one unit’s assignment to the treatment group and another unit’s assignment to the control or comparison group. This is not to imply that the groups are the same on every characteristic – it is very possible that differences may occur; however, these differences can be assumed to be randomly distributed and are accounted for in the probability distributions that underlie statistical tests of significance. Regardless, neither the treatment group nor the control group should have an advantage over the other on the basis of known or unknown variables. Thus, randomized experiments are the only design that allows the researcher to assume statistically unbiased effects (e.g., Boruch 1997).

The goal of most randomized experiments in criminology and criminal justice, as in other social science fields, is to disentangle the impact of the treatment or intervention from the impact of other factors on the outcomes that are to be tested. A randomized experiment allows the researcher to attribute differences between the groups from pretest to posttest as a result of the treatments or interventions that are applied. At the conclusion of the study, the researcher is able to assert, with confidence, that the difference is likely a result of the treatment and not due to other confounding factors. It is more difficult for nonrandomized studies, even a high-quality quasi-experimental design, to make this assertion. This advantage is underscored by Farrington (1983):

The unique advantage of randomized experiments over other methods is high internal validity. There are many threats to internal validity that are eliminated in randomized experiments but are serious in non-experimental research. In particular, selection effects, owing to differences between the kinds of persons in one condition and those in another, are eliminated. (1983, p. 260)

Other Experimental Designs

Randomized experiments are distinguished from quasi-experiments and natural experiments by the random assignment of subjects or units. Indeed, these other methods have been developed as a way to approximate “true” experiments when random assignment is not possible. For example, researchers use matching, statistical methods, a comparison group, time series analyses, and other methods to create a quasi-experimental design (QED).

Researchers also take advantage of naturally occurring events to conduct natural experiments. Natural experiments often occur due to an unplanned event, which can allow for an evaluation of a particular factor or intervention. For example, when overcrowding forces the early release of certain prisoners, researchers can use this unplanned event to evaluate the impact of early release on recidivism. Although this example may show a direct short-term impact of early release on recidivism, it still suffers from potential for selection bias, as those selected for early release may be very different than prisoners remaining incarcerated.

Although QEDs and natural experiments are often necessary and can have high interval validity compared to other designs, they are generally considered less rigorous than a well-implemented randomized experiment, because they cannot control for unknown factors.

There is some debate among criminologists and across other fields in social and physical sciences, as to the type of bias that results from utilizing nonrandomized rather than randomized studies when examining program or intervention effects. Some may argue that the differences between well-designed nonrandomized studies and randomized experiments are negligible if not slightly skewed towards randomized experiments (Lipsey and Wilson 1993); however, it has been shown that in criminal justice nonrandomized experiments routinely overestimate program success when compared to randomized experiments (Weisburd et al. 2001).

Example Of A Criminological Experiment

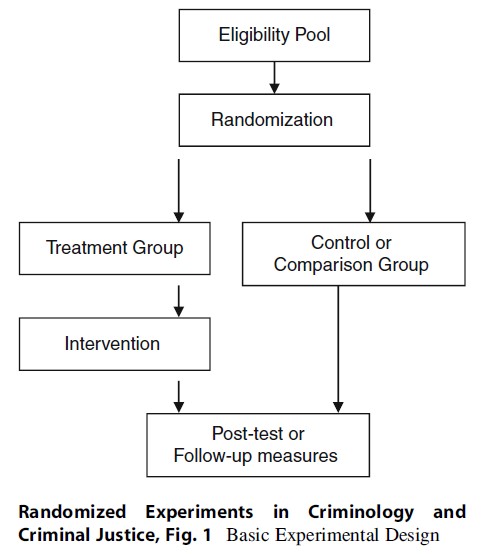

The general structure of experiments in criminology is usually similar in design regardless of the area or question of interest. Generally, experiments in criminology start with an eligibility pool, randomization, group allocation, and posttest measures relevant to the dependent variable of interest (Fig. 1).

The eligibility pool is made up of those participants or units that are eligible for the experiment. Units of analysis can be individuals or aggregated groups or other entities that are often found in clusters. For example, in an experiment that evaluates the impact of increased foot patrol on crime rates, the eligibility pool may be individual officers who “walk the beat,” in a specific area, and who have a specific number of years of experience. Or the unit of analysis could be the geographic area or “beat” that will be assigned to different conditions. The eligibility pool is thus comprised of those patrol officers (or patrol “beats”) that meet criteria for inclusion in the study.

Next, researchers randomly assign members from this pool of eligible participants or units to the study conditions – often a treatment group and a control or comparison group. Historically, randomization was carried out through a simple coin flip. There are now many ways to randomize subjects, but most often researchers rely on computerized statistical software to carry out randomization. Some researchers may simply use the rule of odds and evens – that is, assigning every other case to one particular group. This is often referred to as alternation and is considered quasirandom assignment as the assignment of the numbers used is not actually random. The most critical factor in randomization, however, is that each case has the same probability or likelihood of being selected for the control group as the experimental group and that the assignment is based purely on chance. Garner (1977) argued that “equal probability assignment” should replace “random assignment” when discussing such studies with practitioners as it sounds orderly and fair rather than chaotic and unfair.

In the usual criminological experiment, eligible cases are randomly assigned to one of two groups – treatment or control. Experiments in criminology may have more than two groups. But typically, an experiment is comprised of a group that receives the treatment or intervention and a control or comparison group that does not. It is also quite common in a criminological experiment for the control group to actually receive something rather than nothing. For example, in the foot patrol example, the control group may receive treatment as usual, or the same number of foot patrol officers as typically employed.

Experimental designs can include any number of outcomes, from one to scores. If the randomization was implemented with fidelity, it should produce two equivalent groups on the pretest or baseline measures related to the outcome of interest. The researcher then conducts analyses to determine if the intervention had any impact on the posttest or follow-up measures of the outcomes of interest.

An Illustrative Example Of A Place-Based Randomized Field Study: The Minneapolis Hot Spots Patrol Experiment

Randomized experiments in criminal justice, as with most fields, involve the random assignment of individuals. However, as shown in the design example above, it is possible to randomized larger units such as schools, police beats, transportation stops, or city blocks. When these larger entities are randomized, it is often referred to as cluster, block, or place-based randomized trials. The Minneapolis Hot Spots Patrol Experiment (Sherman and Weisburd 1995) provides an example of a place-based experimental design. In that study, the investigators wanted to determine in the least equivocal manner whether intensive police patrol in clusters of addresses that produced significant numbers of calls for service to police, also known as “hot spots,” would reduce the levels of crime calls or observed disorder at those places.

To conduct the experiment, the investigators established a pool of 110 hot spots that were eligible for random assignment. This pool of eligible hot spots was then randomly assigned to the innovation group receiving intensive police patrol and a control group that received normal police services. In the Minneapolis study the investigators randomly assigned the hot spots within statistical blocks, or groups of cases that are alike one to another on characteristics measured before the experiment. Such block randomization is not required in randomized experiments, but as noted above is a method for further ensuring the equivalence of treatment and comparison or control groups.

The strength of the randomized experiment, if it is implemented with full integrity, is that it now permits the investigators to make a direct causal claim that the innovation was responsible for the observed results. If the researchers had simply looked at changes over time at the treated hot spots, it would have been difficult to claim that the observed changes were due to treatment rather than a natural change in levels of crime or disorder over time. Similarly, if the researchers had tried to statistically control for other potential causes in order to isolate out the effect of treatment, it could be argued that some unknown or unmeasured factor was not taken into account. In the Minneapolis study the researchers found a statistically significant difference between the treatment and control hot spots. Random allocation of subjects to treatment and control conditions allowed the authors to assume that other factors had not systematically confounded their results.

History Of Randomized Experiments In Criminology And Criminal Justice

While there is evidence that randomization in experiments was used as early as 1885 (Hall 2007), most scholars credit Sir Ronald Fisher and his publication on The Design of Experiments (1935) as the first discussion that argues for randomization as a necessity to establish group equivalence. The medical world was the first field that used randomized experiments extensively in the field. The first randomized experiment is credited to Austin B. Hill and associates in a 1948 paper on streptomycin treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. The work done by Hill during this time is still highly celebrated in the medical field as it paved the way for the first half century of randomized control trials (Weisburd and Petrosino 2004).

Randomized trials in criminology may have started as early as 1937 with the CambridgeSomerville Youth Study, but the publication was not issued until 1951 (Powers and Witmer 1951) – this is likely the first criminological trial in modern times. Researchers created a youth eligibility pool from youth who were considered as “troubled kids” by their teachers and police, and matched the youth on basic characteristics. Next in the experiment, researchers randomly assigned the youth to a treatment counseling group or a no-treatment control group. The findings consistently stated no positive gains and even negative gains for the treatment group (Weisburd and Petrosino 2005).

Although Fisher and Hill generated much excitement around randomized trials in their respective fields, criminological trials were sparse in the first decade since its debut in the field. Experiments in criminology only found momentum after Campbell and Stanley (1963) published their comprehensive guide to Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. The publication provided researchers with a design template to carry out high-quality criminological research. Even then the randomized trial was touted as champion in the hierarchy of experimental design for its high degree of internal validity (Weisburd and Petrosino 2004). Randomized trials during President Lyndon Johnson’s campaign – perhaps spurred on by the credibility seen throughout the medical world – were used frequently to evaluate the social endeavors designed in the “Great Society” campaign. Soon after this federal adoption, randomized trials fell out of favor with the administration as researchers would consistently report that government programs show no impact or even negative outcomes. Despite Campbell’s (1969) decree that

The United States and other modern nations should be ready for an experimental approach to social reform, an approach in which we try out new programs designed to cure specific social problems, in which we learn whether or not these programs are effective, and in which we retain, imitate, modify, or discard them on the basis of apparent effectiveness on the multiple imperfect criteria available (Campbell 1969, p. 409)

randomized experiments in criminology faded from center stage for more than a decade (Weisburd and Petrosino 2004). David Farrington’s (1983) review of high-quality randomized experiments in criminal justice showed that between 1957 and 1981 there were only 41 eligible studies, of which only 35 included offending outcomes. Probably more important than the fact that only 30% of the studies found a significant effect is the relative dearth of experiments in criminology compared to other social and physical sciences (Farrington 1983).

However, experimentation in criminology received a boost during the 1980s. First, the Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment (Sherman and Berk 1984), in which 330 male domestic violence suspects were assigned to the treatment (arrest on the spot) group or one of two comparison groups – mediation or separation for 8 h – was conducted. A 6-month follow-up found that arrests significantly reduced subsequent domestic violence, and the study received wide media attention and led to police departments across the USA to adopt mandatory arrest policy for misdemeanor domestic violence incidents. These results also led the US Department of Justice, under James Stewart, to support randomized experiments (Farrington and Welsh 2005; Weisburd and Petrosino 2004). Although replications in other cities were conducted with mixed results, this study is still considered a monumental factor in the promotion of randomized experiments in criminology and criminal justice (Farrington and Welsh 2005). In fact, the exposure from the Minnesota study and subsequent works led to NIJ funding more than two dozen experiments over the next several years (Weisburd and Petrosino 2004).

It was just 2 years later that Farrington et al. (1986) released their acclaimed work Understanding and Controlling Crime, which emphasized the unequivocal need to use randomized experiments whenever possible in criminological evaluations. The investment in experimental criminology continued in waves through the 1990’s and has increased considerably into the twenty-first century.

Experiments As The Gold Standard In Criminology And Criminal Justice

There is a strong consensus that experiments are the gold standard for evaluation research in criminology and criminal justice. This is reinforced by seminal reviews that appraise the methodological quality of evaluation evidence. For example, Sherman et al. (1997) conducted a comprehensive review of evaluations across many criminal justice sectors to produce their report to congress on crime prevention entitled, “What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising.” As part of the review, Sherman and colleagues developed the Maryland Scientific Methods Scale (SMS), a set of criteria for scoring – evaluations, largely based on internal validity. The highest rating, “5,” is reserved for evaluations that utilize “random assignment of program and control conditions to units” (Farrington 2003).

Another example of the rising status of experiments is the creation of organizations to promote such studies. For example, the Academy of Experimental Criminology was founded in 1998 to recognize researchers who successfully led randomized field experiments (Weisburd et al. 2007). The American Society of Criminology created a Division on Experimental Criminology (DEC).

It is also the case that the use of experiments in justice field settings is increasing. As a follow-up to earlier work, Farrington and Welsh’s (2005) review showed that randomized experiments with offending outcomes that fit their review criteria grew from 35 between 1957 and 1981 to 1983 between 1982 and 2004 – an increase of over 200 %.

Barriers To Randomized Experimentation

Although randomized experiments have been widely recognized for their internal validity rigor for over 50 years, they comprise a comparatively small portion of the evaluation portfolio in criminology. For example, Petrosino (2003) examined abstracts of impact studies relevant to childhood intervention in the leading bibliographic databases for each field. The proportion of abstracts to RCTs or possible RCTs ranged from 17 % to 18 % for juvenile justice and K-12 education to 68 % in health care. And despite the increase, Farrington and Welsh (2005) were still discouraged to find as few RCTs as they did in their survey of the literature.

Why do randomized experiments encompass a small percentage in the overall catalog of research when they are widely regarded as the gold standard in research? Farrington and Welsh (2005) note that although randomized experiments are advantageous, there are “many ethical, legal, and practical difficulties that face researchers who wish to mount a randomized experiment.” For one, some argue that it is legally irresponsible to provide treatment or judicial sanctions at random or to withhold necessary treatment from individuals. Boruch (1997) and others have countered this argument by noting that it is unethical to provide untested treatments and that programs are sometimes provided to persons haphazardly without evidence of their effectiveness.

Another barrier to RCTs is that randomized trials are considered too expensive. The feature of the RCT that generates the highest costs is actually not specific to randomized experiments: it is the longitudinal nature of the data collection (i.e., following treatment and control units and collecting data on various outcome measures). The Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy (2012) has argued for using large-scale administrative data for outcomes (as opposed to field data collection from surveys or interviews) to decrease costs in data collection.

Another common criticism of randomized experiments is that it emphasizes internal validity, but at the expense of external validity. External validity is the ability to generalize findings from a study to other settings. Some researchers argue that experiments set up an artificial setting with treatment and control conditions that do not approximate real world conditions.

Problems In The Field

The three major issues that threaten experimental findings of randomized experiments are as follows:

- If the random assignment protocol was violated in substantive ways

- If there was substantial attrition or differential loss of subjects from the study

- If there was no clear contrast between the treatment program and control condition

Randomization integrity. Randomization is the cornerstone of true experiments. There are a number of missteps that may adversely affect the integrity of random assignments. For example, program staff may have a vested interest in manipulating the randomization assuring certain participants are funneled into certain groups. It has been shown that this type of violation occurs more frequently with practitioners than with researchers; thus, whenever possible, researchers should control the randomization and practitioners should remain blind to the group allocation. Furthermore, researchers should determine the eligibility pool with practitioners before randomization occurs, monitor assignment throughout the study, and train practitioners and data collection staff in the importance of research integrity (Petrosino 2005).

Attrition. Attrition is the loss of cases from study groups after randomization. Researchers must also be proactive in retention efforts to ensure minimal attrition throughout the study. It is very difficult, especially in the criminal justice field, to track participants for long periods of time, which is required to assess intermediate and long-term treatment impact. When participants attrite for one study group more so than another, it is called differential attrition. Differential attrition is particularly hazardous when determining confidence in the treatment impact, because often this causes a change in the composition of the groups. This is a threat to the experiment’s internal validity when the treatment group differs in some important way from those who leave the study (Petrosino 2005).

Treatment-control group contrast. The intent when conducting an experiment is to test a specific treatment’s impact on a given outcome variable relative to the comparison condition. To test the impact, the treatment and comparison must indeed be distinguishable from one another. On occasion, when the treatment is only a slight alteration from the comparison condition, it may only take a small change in intensity of treatment or comparison condition to create indistinguishable groups. This difference in conditions must be maintained; otherwise, the comparison and any results would be meaningless (Weisburd and Petrosino 2004).

Conclusion

Despite barriers to experiments and the hurdles researchers must jump to conduct a well-implemented RCT, experimental criminology has grown exponentially over the past several decades. There are signs that this trend will continue in criminology. First, the publicity from successful medical field trials has led to greater acceptance of this research in other fields. Second, tighter governmental accountability has created a surge in evidence-based research. The public expects the programs funded by tax dollars to be rigorously tested (Weisburd and Petrosino 2005).

Bibliography:

- Boruch RF (1997) Randomized experiments for planning and evaluation: a practical guide. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Braga AA, Weisburd DL, Waring EJ, Mazerolle LG, Spelman W, Gajewski F (1999) Problem-oriented policing in violent crime places: a randomized controlled experiment. Criminology 37:541–580

- Campbell DT (1969) Reforms as experiments. Am Psychol 24:409–429

- Campbell DT, Stanley J (1963) Experimental and quasiexperimental designs for research. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston

- Coalition for Evidence-based Policy (2012) Rigorous program evaluations on a budget: how low-cost randomized controlled trials are possible in many areas of social policy. Author, Washington, DC

- Farrington DP (1983) Randomized experiments on crime and justice. In: Torny M, Morris N (eds) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, vol 4. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 257–308

- Farrington DP (2003) Methodological quality standards for evaluation research. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 587:49–68

- Farrington D, Welsh B (2005) Randomized experiments in criminology: what have we learned in the last two decades? J Exp Criminol 1:9–38

- Farrington DP, Ohlin LE, Wilson JQ (1986) Understanding and controlling crime. Springer, New York

- Fisher RA (1935) The design of experiments. Oliver and Boyd, London

- Garner J (1977) Role of congress in program evaluation – three examples in criminal justice. Prison J 57(l):3–12

- Hall N (2007) R.A. Fisher and his advocacy of randomization. J Hist Biol 40(2):295–325

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB (1993) The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment: confirmation from meta-analysis. Am Psychol 48:1181–1209

- Petrosino A (2003) Estimates of randomized field trials across six areas of childhood intervention. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 589:190–202, Special Issue on Randomized Experiments in the Social Sciences, September

- Petrosino A (2005) Randomized field trials in the U.S. to evaluate justice programs: a briefing. Japan J Sociol Criminol 30:56–71

- Petrosino AJ, Boruch RF, Rounding C, McDonald S, Chalmers I (2000) The Campbell Collaboration Social, Psychological, Educational and Criminological Trials Register (C2-SPECTR) to facilitate the preparation and maintenance of systematic reviews of social and educational interventions. Eval Res Educ 14(3/4):206–219

- Powers E, Witmer H (1951) An experiment in the prevention of delinquency: the Cambridge-Somerville youth study. Columbia University Press, New York

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT (2002) Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston

- Sherman LW, Berk RA (1984) The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. Am Sociol Rev 49(1):261–272

- Sherman L, Weisburd D (1995) General deterrent effects of police patrol in crime ‘hot spots’: a randomized study. Justice Q 12(4):625–648

- Sherman LW, Gottfredson D, MacKenzie D, Eck J, Reuter P, Bushway S (1997) Preventing crime: what works, what doesn’t, what’s promising. A report to the United States Congress. University of Maryland, Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, College Park

- Weisburd D, Mazzerolle L, Petrosino A (2007) The academy of experimental criminology: advancing randomized trials in crime and justice. Criminologist 32:1, 3–7

- Weisburd D, Petrosino A (2004) Experiments, criminology. In: Kempf-Leonard K (ed) Encyclopedia of social measurement. Academic, San Diego

- Weisburd D, Petrosino A (2005) Randomized experiments. In: Miller JM, Wright R (eds) Encyclopedia of criminology. Routledge, New York

- Weisburd D, Lum C, Petrosino A (2001) Does research design affect study outcomes in criminal justice? Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Res 578:50–70

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.