This sample Rational Choice, Deterrence, and Crime Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

This research paper reviews sociological contributions to the study of rational choice, deterrence, and crime. It reviews empirical research on the deterrence question, including macro-level studies of aggregate crime rates, micro-level studies of individual perceptions of sanction risk, and experimental studies of specific deterrence and domestic violence. It then shows the relevance of sociological research for specifying the broader context of punishment, which reveals negative externalities of mass incarceration in the USA, such as the pernicious stigmatizing effects of incarceration, the undermining of the legitimacy of the law within disadvantaged communities, and the loss of community cohesion and social capital. Such negative externalities produce criminogenic social conditions, which, in turn, undermine deterrent effects.

Rational Choice, Deterrence, And Crime

The deterrence doctrine is rooted in the writings of the classical school of criminology, and in particular, those of Caesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham. Influenced by the prevailing ideas of the enlightenment period, Beccaria argued that human beings freely enter into a social contract with the state, relinquishing some liberty in exchange for the protection of their individual rights. In exchange, individuals would give the state the right to punish those who violated criminal laws, consisting of a written record of the terms of the social contract. Punishments would be swift, certain, and just severe enough to offset the pleasures of crime and thereby deter the public from criminal behavior. The underlying behavioral assumption is that human beings are rational and hedonistic, and weigh the pleasures and pains associated with different behaviors. When the pleasures outweigh the pains associated with criminal behavior, individuals will violate the law. These ideas underlie the system of justice used under Anglo-Saxon law, and motivated early sociological studies of deterrence until a formal expected utility model was specified by the economist Gary Becker.

Expected Utility Models Of Crime

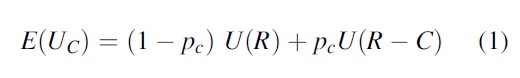

Becker (1968) made a seminal contribution to the study of deterrence by specifying a neoclassical theory of criminal behavior. Arguing that the same economic principles explaining decisions made by firms and household members should also explain criminal behavior, Becker (1968:177) drew on von Neumann and Morgenstern’s expected utility theory of risky decisions under uncertainty to specify a simple utility function for committing crimes:

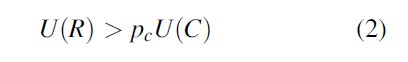

where E(UC) is the expected utility of crime, pc is the probability of getting arrested and punished, (1 -pc) is the probability of getting away with crime, R is the return (both monetary and psychic) from crime, C is the cost of punishment (e.g., a fine or prison sentence), and U is a utility function translating punishments and rewards to a common metric. The expected utility model assumes that individuals have complete and transitive preference orderings for all possible decision outcomes. If we ignore noncriminal behavior or assume that the expected utility from noncrime is absorbed in C as an opportunity cost, we can specify that a crime will occur when E(UC) > E(UN) = 0, so that from equation (1), a crime will occur when the following holds:

That is, when the returns to crime exceed the punishment, weighted by the probability of detection, an individual will commit a crime. The policy implication here is that by increasing the certainty and severity of punishment, the probability of crime will be reduced. Crime can also be reduced by lowering the rewards to crime – by defending public spaces through increasing surveillance, employing security guards, and using technological advances in metal detection, alarms, locks, fences, and the like (see McCarthy 2002). Historically, following Becker’s (1968) work, most microeconomic research on crime has focused on the policy implications of increasing the certainty and severity of punishment.

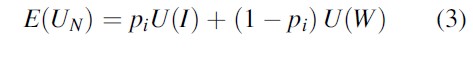

Criminal decisions, of course, consider the utility of noncrime as well as crime, and therefore, one might specify a utility function for noncriminal activity (e.g., Bueno de Mesquita and Cohen 1995):

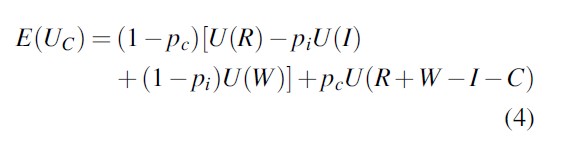

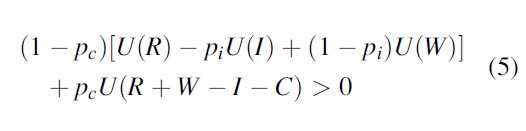

where I is income (returns to conventional activity), pi is the probability of obtaining I (through having high social status, resources, or talent), and W is welfare or the social safety net for those who cannot obtain I (i.e., pi = 0). Combining equations (1) and (3) yields:

If follows that a crime will be committed when:

From a policy point of view, the probability of crime can be altered not only through criminal justice policies that increase the certainty and severity of punishments or that change defensible space, but also through policies that increase the utility from noncriminal activity. For example, job training, higher education, and other programs to enhance human and social capital may reduce the attractiveness of crime by increasing pi, the probability of obtaining a desired income from legitimate activities. Returns to conventional activity include not only income but also social status and prestige, self-esteem, and happiness; policies that increase these quantities by inculcating strong commitments to conventional institutions may help reduce crime.

Limited Rationality And Crime

Criminologists, following cognitive psychologists, have questioned the assumptions of the expected utility model, arguing that criminals are unlikely to have access to full information and unlikely to conduct complex calculations necessary to maximize expected utility. For example, the utility maximization theory is commonly criticized for assuming (1) that the actor knows the probabilities of certainty and severity of crime, and (2) that criminals act on a rational calculation, rather than by impulse, either under the influence of alcohol or in responding to opportunities. In responding to this criticism of rational choice and crime, Cook (1980) drew on Herbert Simon’s work on bounded rationality, and suggested that criminals may use standing decisions or rules of thumb in making decisions about crime – particularly in situations of high stress, emotion, or inebriation. Moreover, Cook argued that rational choice theories of crime need a theory of the communication of threats, and pointed to the role of the media, presence of law enforcement, personal experience, and observation of peers as important ingredients of such a theory.

Clarke and Cornish (1985) attempted to integrate rational choice with conventional criminological theories, such as social learning theory, and developed a model in which actors’ pursuit of general needs and previous learning (experiences with crime, contact with police, conscience and morality, self-perception, and foresight) led to evaluation of legitimate and illegitimate solutions to produce a “readiness” to commit burglary. Readiness may lead to a decision to commit burglary, which is followed by a proactive assessment of potential middle class targets based on accessibility, police patrols, security, cover, affluence, and no one being at home. The evaluation of target accessibility is consistent with routine activities theory, which hypothesizes that criminal events result from the intersection of motivated offenders, suitable targets, and the absence of capable guardians.

Empirical Research On Rational Choice And Deterrence

Empirical research on rational choice and deterrence has made considerable methodological strides, moving from cross-sectional studies to longitudinal and panel designs, grappling with the identification problem, and considering experimental designs. Beginning with Jeremy Bentham, deterrence theory has traditionally distinguished between general and specific deterrence. General deterrence refers to an act or threat of punishment deterring the general public from committing crimes; specific deterrence refers to the special case of deterring the punished individual from committing future crimes. While these two forms of deterrence are theoretically distinct, may influence people through different mechanisms, and consequently may imply distinct punitive policies, they are often hard to tease apart empirically. Of the empirical work reviewed here, aggregate research – especially studies examining the effect of new punishment policies on rates of offending – often conflates the effects of specific and general deterrence (Durlauf and Nagin 2011). Individual-level studies can be more explicit about separating out the effects of each.

Studies Using Aggregate Data

Over the past four decades, a spate of empirical studies of deterrence by criminologists, sociologists, and economists have used aggregate data to examine whether individuals are deterred by the certainty and severity of punishment (for a review, see Nagin 1998), often employing instrumental variables to identify reciprocal effects between rates of imprisonment and rates of crime. Durlauf and Nagin (2011) provide an excellent review of empirical work on deterrent effects of incarceration, summarizing recent findings as well as identifying important issues in aggregate research on deterrence. Studies of the severity of sanctions – often operationalized as differences in the length of incarceration – have found only modest deterrent effects of severity of punishment. Studies of the deterrent effect of capital punishment – considered the most severe of all state sanctions – have historically yielded disparate results, with recent evidence that findings of deterrent effects of capital punishment were based on incorrect modeling procedures (Durlauf et al. 2012). However, there is evidence of significant deterrent effects of certainty – operationalized as greater police presence on the street, and more aggressive policing practices.

While aggregate research examining change in the crime rate has contributed much to the understanding of the deterrent properties of various policy changes, it has been criticized for several shortcomings. First, aggregate research is unable to distinguish the effect of deterrence from the effect of incapacitation on crime (Durlauf and Nagin 2011). Second, this research has not accounted for heterogeneity (especially at the state level) of policy adherence. This is problematic because systems of formal control differ not only at the state level, but also by county, city, and sometimes community. Additionally, individuals may be most aware, and concerned with, local formal punishment and detection policies rather than those at the county or state level (Apel 2012). Third, most aggregate studies do not distinguish between awareness of deterrence policy, and often assume that individuals have perfect information with which to assess risk of being caught and punished (Durlauf and Nagin 2011). Recent research indicates that there are significant gaps in policy awareness, with experienced offenders being more informed than others (Matsueda et al. 2006; Apel 2012), showing a need to treat utility maximization and possession of information as separate effects of deterrence policy on observed behavior. The next section reviews research on individuals’ subjective evaluation of the severity and certainty of punishment, which has emerged as one fruitful alternative to aggregate deterrence research.

Studies Using Survey Data Of Individuals

Aggregate tests of the deterrence hypothesis assume that actors know the objective certainty of arrest and imprisonment (Nagin 1998). By contrast, subjective expected utility models relax this assumption, replacing the single known objective probability with a distribution of subjective probabilities. Subjective utility models are still rational models because the statistical mean of the subjective probability distribution is assumed to fall on the value of the objective probability (Nagin 1998). Empirical research from a subjective expected utility framework uses survey and vignette methods to measure perceived risk of punishment directly from respondents, rather than inferring it from behavior through the method of revealed preferences.

Early empirical research by sociologists used cross-sectional data and found small deterrent effects for certainty of punishment but not for severity (e.g., Williams and Hawkins 1986). Respondents who perceive a high probability of arrest for minor offenses (like marijuana use and petty theft) report fewer acts of delinquency. Such research has been criticized for using cross-sectional data in which past delinquency is regressed on present perceived risk, resulting in the causal ordering of the variables contradicting their temporal order of measurement.

To address this criticism, sociologists have turned to two-wave panel models and found, for minor offenses, little evidence for deterrence (perceived risk had little effect on future crime) and strong evidence for an experiential effect (prior delinquency reduced future perceived risk) (see Williams and Hawkins 1986; Paternoster 1987). Piliavin et al. (1986) specify a full rational choice model of crime, including rewards to crime as well as risks, and find, for serious offenders, that rewards exert strong effects on crime, but perceived risks do not.

Recent longitudinal survey research has used more sophisticated measures of risk, better-specified models, and better statistical methods. Matsueda et al. (2006) specify two models based on rational choice. First is a Bayesian learning model of perceived risk, in which individuals begin with a baseline estimate of risk, and then update the estimate based on new information, such as personal experiences with crime and punishment or experiences of friends. Second is a rational choice model of crime, in which crime is determined by prior risk of arrest, perceived opportunity, and perceived rewards to crime, such as excitement, kicks, and being seen as cool by peers. Using longitudinal data from the Denver Youth Survey, Matsueda et al. (2006) find support for both hypotheses: perceived risk conforms to a Bayesian updating process, and delinquency is determined by perceived risk of arrest, rewards to crime, perceived opportunities, and opportunity costs. A recent study by Anwar and Loughran (2011) extends the risk updating model to high-risk offenders, finding further evidence for a Bayesian-style learning model. The study also finds that experiencing a deterrent signal about a specific type of crime results in a generalized posterior where all crimes are considered more risky.

In addition to risk updating, perceptual research has focused on other aspects of individual assessment of risk, such as interpretation of the risk signal. Loughran et al. (2011) build on Lawrence Sherman’s distinction between level and ambiguity of sanction certainty, and test whether individuals are ambiguity averse – that is, interpret uncertainty as an added risk. The authors find support for ambiguity aversion in assessment of sanction certainty, but also observe ceiling effects, where extremely risky and uncertain situations will be perceived as slightly less risky than certain samelevel risk. Loughran et al. (2011) additionally find that ambiguity aversion holds only for property crimes, and not face-to-face crimes, noting that property crimes may be more amenable to deterrence.

Vignette surveys examine perceived deterrent effects within a richer depiction of a scenario, which mimics actual situations of crime. Here, a crime scenario is depicted in a short written paragraph, with specific elements of the scenario – such as the presence of police or witnesses and potential monetary returns – randomly rotated across vignettes. Respondents are asked to assess the probability of getting caught or obtaining rewards from the crime and also asked their intentions of committing the crime depicted. By asking their future intentions of committing crime, vignette studies resolve the causal order problem, under the assumption that intentions are good predictors of actual behavior. A weakness of vignettes is the potential for a response effect: respondents who report high risk of arrest may be unlikely to admit to an intention to commit the crime due to social desirability effects. Vignette studies of deterrence and rational choice generally find robust effects of deterrence: certainty has a substantial effect on criminal intentions, while severity has modest effects. This holds for tax evasion, drunken driving, sexual assault, and corporate crime (see Nagin 1998, for a review).

A recent line of research in clinical psychology has focused on linking cognitive developmental differences between adults and adolescents (including middle and late adolescence) to differential decision making and criminal participation. New analyses suggest that cognitive immaturity in older adolescents and young adults, including a lesser ability to engage multiple regions of the brain to problem-solve coupled with increased dopamine activity, causes them to be more impulsive, more vulnerable to peer influence, and more likely to discount the future than adults who are in their mid-twenties and older (see Steinberg 2009). This research provides a developmental basis for differences in adolescent behavior previously noted by sociologists and criminologists, such as committing crime in groups, and discounting future punishment costs. Furthermore, these findings suggest that individuals in their late teens and early twenties may still be in a developmental stage that is not as amenable as adults to current policies of deterrence, which may explain differential rates of young adult participation in criminal activity. Such research has obvious policy implications for the distinction between juvenile and adult criminal justice.

The recent advances in perceptual deterrence have significantly added to the specification of the process by which individuals understand and respond to the policies of deterrence. However, sociological research on consequences of punishment has raised awareness of additional mechanisms that have the potential to alter individual utility functions and undermine the efficiency of deterrence. The next sections outline what is known about the ways in which the current system of punishment in the USA can affect individual utility functions and behavior.

Studies Of Specific Deterrence Using Experiments On Domestic Assault

Research on specific deterrence faces the daunting task of addressing non-equivalent treatment (e.g., incarceration) and control groups (e.g., probation). Offenders who are incarcerated are likely to be more crime prone than offenders who are not incarcerated, and thus, unobserved heterogeneity is likely to bias comparisons between incarcerated and non-incarcerated offenders. A line of research that addresses this problem uses an experimental design to examine the specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault on recidivism rates. Sherman and Berk (1984) conducted such an experiment by randomly instructing police to arrest domestic assault offenders versus merely counseling others. Contrasting this with a labeling effect, in which arrest may stigmatize offenders and amplify deviance, Sherman and Berk (1984) found a significant deterrent effect: arrested offenders were less likely to re-offend than nonarrested offenders. As a result, laws mandating arrest for domestic assault offenders spread across the country. Because this study was limited to one city (Minneapolis) and suffered some methodological problems – such as police departing from random assignment – the National Institute of Justice funded a set of replication studies across the USA. Generally speaking, those studies did not replicate the specific deterrent effect: overall, arrested offenders were not significantly less likely to recidivate. They did find, however, that arrest deterred a subpopulation of offenders – namely, those who had stronger stakes in conformity, such as marriage and employment (e.g., Berk et al. 1992). Thus, arrest for domestic assault may deter future assaults for those individuals who are committed to conventional society, and who consequently, have more to lose by arrest and likely incarceration. Commitment to society constitutes a key component of the broader context of punishment.

The Social Context Of Deterrent Effects

Sociologists critical of using policies of deterrence as a panacea for the crime problem have emphasized the societal context in which punishment is carried out. Most research on the broader contexts of crime and punishment has not adopted a rational choice framework. Nevertheless, such research has important implications for a rational choice theory of crime, and in particular, for identifying limitations of deterrent effects. A key concept here is stigma. Research has found that small amounts of informal stigma, which is analogous to public shaming, may enhance specific deterrent effects. But widespread or permanent stigmatization of distinct groups of people can have substantial negative externalities, at times amplifying rather than deterring crime. This research has its roots in sociological labeling theory, which stresses the negative consequences of the criminal justice system, and Braithwaite’s (1989) theory of reintegrative shaming, which argues that stigmatization without reintegration can amplify the crime problem. We use these ideas to organize research on stigma and crime.

Stigmatization And Crime

Goffman (1963) described stigma as an attribute that spoils an individual’s identity, evokes negative stereotyping by others, and causes the individual to adopt coping strategies when confronted by “normals.” Research and theory on rational choice and deterrence has shown that a specific mechanism that potentially enhances deterrent effects is informal sanctioning by family members and peer groups. That is, if the arrested or convicted offender is stigmatized by significant others – resulting in a loss of social status – the specific deterrent effect of the arrest or conviction will be strengthened (see Paternoster 1987). This effect could also enhance general deterrence as other members of society observe the stigmatizing effects of punishment. Rebellon, Piquero, Tibbets, and Piquero (2010) show that fear of arrest deters mainly through the expected shame from friends and family of the potential offender. Stigma, however, is a relative concept; its negative effects are dependent on its distribution in a population. Having a disfiguring scar may be enormously stigmatizing in a population whose members have no scars, but less so in a population of army veterans in which scars are frequent. Moreover, the deterrent properties of stigma may have within-individual thresholds: if an individual is severely and permanently stigmatized, any future stigmatization or shaming is rendered ineffective. In the following section, we outline how policies of deterrence may be undermined when stigmatization exceeds such population and individual-level thresholds.

Stigma And Population Thresholds

Because stigma is a relative term, its negative effects may exhibit a threshold effect or tipping point in a given group or population. When punishment is a relatively rare event, the stigmatizing effects are dramatic. As the incarceration rate of a subpopulation increases, the status of being a felon becomes more commonplace, and the effects of stigma shrink (Nagin 1998). If all members of the subpopulation receive felon status, stigma reduces to zero. Even if stigma reinforces a deterrent effect, that effect is subject to a tipping point, after which the effect declines. Thus, it is possible that mass incarceration has undermined the stigmatizing effects of having a criminal record, as more and more members of a given group – young African-American men from disadvantaged backgrounds – share the status of having a criminal record. For example, Clear (2007) and Anderson (1999) describe the spatial concentration of incarceration in poor African-American communities, where offenders cycle in and out of neighborhoods in which they resided before initial contact with the law. In such neighborhoods, incarceration may become normative, and felon status may lose its stigmatizing effect. From a rational choice perspective, the cost of incarceration has diminished in such communities, which attenuates deterrent effects.

Within-Individual Thresholds: Shaming, Stigmatization, And Reintegration

Even without reaching population-level thresholds, the effects of stigma can change from deterrent to criminogenic if stigma becomes a serious and permanent experience for an individual. The concept of permanent, self-reinforcing stigma lies at the heart of sociological labeling theories, which posit that negative labeling can at times amplify, rather than deter, crime. For example, minor forms of deviant or mischievous behavior, viewed as play by children, may be seen as bad, evil, or portending of more serious deviance by the adult community. Adults often respond by labeling the child as “evil” or “bad” and informally punishing the child. Repeated negative interactions with the community may leave the child cut off from conventional peers, stigmatized as a bad kid, and caught up with the juvenile justice system, ultimately leading the individual to adopt the stigmatizing label as permanent trait, viewing themselves as a criminal and engaging in criminal behavior. Labeling theorists emphasize the negative effects of labeling and pose the counterfactual: might the youth have been better served if their initial minor forms of delinquency had been treated as mere mischief and avoided the process of negative labeling and deviance amplification?

Braithwaite (1989) elaborated on deviance amplification with his theory of reintegrative shaming. Consistent with labeling theory, Braithwaite argues that often the punitive sanctions of the legal system amplify rather than deter crime by stigmatizing and segregating the offender from conventional society. In contrast, a system of reintegrative shaming would shame the offender – via informal disapproval by significant others (family, friends, and other community members) who are respected and trusted by the offender – followed by a program of reintegration of the offender back into conventional society. Braithwaite argued that punishment is most efficient when administered within a context of respect and love – rather than anger, retribution, and rejection – and within a context in which the offender is welcomed back into society. Consequently, for the offender, the threat of future shaming will maintain a deterrent effect, as the offender has something important – his or her renewed status – to lose.

Empirical research finds some support for ideas of restorative justice and reintegrative shaming. For example, the use of restorative justice as a model for conflict resolution and restitution may result in greater satisfaction for offender and victims compared to a traditional court-centered approach. Offenders who received restorative justice may also have lower recidivism rates than the offenders who receive court-centered justice (Braithwaite 1999). Informal shaming may be a key cost of offending and enhance deterrent effects (e.g., Rebellon et al. 2010).

Theories of labeling and reintegrative shaming provide a theoretical framework within which to review recent sociological research into the social context of punishment. The key theoretical point is that increases in the certainty and severity of punishment may produce a deterrent effect, but in the absence of policies of reintegration, may also produce massive stigmatization of a population, a negative externality that undermines deterrence. This research paper emphasizes the unanticipated negative consequences of punishment, as exemplified in the recent trends of mass incarceration and severe problems of reintegration of offenders in the USA. We focus on the USA as an empirical example because massive incarceration over the last four decades has generated a large population of permanently stigmatized offenders. Problems of stigma and reintegration can become particularly acute if the same class (race, gender, and social class) of offenders is segregated from conventional society, perhaps over generations, resulting in a permanent class of individuals who have little invested in conventional activities, and consequently perceive criminal participation as relatively more rewarding. Recent research suggests this is precisely the situation in contemporary America.

Between 1972 and 2000, the US incarcerated population increased by six times. Western (2006) estimates that, among the male cohorts of 1965–1969, one in five black men had experienced prison by their early thirties. The number for white men was 3 out of 100. Moreover, he reports that nearly 60 % of black men who had dropped out of school were incarcerated by 1999. Clearly, the USA is characterized by mass incarceration, which disproportionately affects disadvantaged young black men. These trends have important consequences for examining rational choice, deterrence, and crime.

Sociological Research On The Individual Consequences Of Punishment

Individuals who have been arrested, convicted, and incarcerated undergo the stigmatizing effects of the criminal justice system, including being handcuffed, appearing in court in jail uniforms, and being incarcerated away from family and friends. This is only the beginning of the stigmatizing process that hampers an offender’s reintegration. Once a felon has paid his or her debt to society, he or she faces additional impediments to reentering society and refraining from future crime. Such obstacles, discussed below, suggest that the US legal system, in conjunction with other institutions, such as labor market and political institutions, operates to stigmatize and segregate the offender from conventional society, working at odds with Braithwaite’s (1989) call for reintegrative shaming.

A criminal record reduces – sometimes permanently – an individual’s employment and earning potential. Empirical research suggests that ex-felons are less likely to be employed, and when employed, tend to be earn lower wages than their labor market counterparts. These results, however, could merely reflect preexisting differences between individuals with and without a criminal record, such as differences in human capital. Consequently, Pager (2007) used a quasi-experimental audit study, in which matched pairs of individuals applied for jobs. She randomly assigned felon status to one of the pair, then reversed that status to obtain the counterfactual condition – what would happen if the felon statuses of the pairs were switched? – and counted the number of callbacks from employers. She found that non-felons were twice as likely as ex-felons to get a callback. That effect was greater for black ex-felons.

Furthermore, a felony conviction revokes the right to be employed in several occupations, and can be grounds for denial of such welfare programs as subsidized housing and financial aid to mothers with children (Wakefield and Uggen 2010). This exacerbates the precarious financial situation of most ex-felons. Fees and fines administered by criminal courts often create accrued debt, which undermines the solvency of economically marginalized criminals. Thus, as personal wealth and employment opportunities and earnings diminish, opportunity costs to crime decrease and illegal markets become more attractive. These persistent declines in returns to legal employment may also reduce the cost of future arrest or incarceration. At the extreme, if felony status makes legal employment virtually impossible, an ex-felon will have little to lose by re-offending.

In most states in the USA, felony status results in a long-term, and sometimes permanent, loss of voting rights (Manza and Uggen 2006). Because felon disenfranchisement disproportionately affects Democratic turnout, it is possible that recent close elections may have turned out differently had felons been allowed to vote (see Manza and Uggen 2006). Moreover, loss of voting rights undermines civic participation, an important source of integration into conventional society.

These negative consequences of punishment can have spillover effects on other commitments to conventional society. Incarceration, and the reduced economic opportunities it spawns, is associated with lower marriage rates (Western 2006) and difficulties providing for children, each of which undermines commitments to the family unit.

Without strong attachments to work, civic, and family life, ex-felons are unlikely to reintegrate into mainstream society. Strong informal ties to conventional society have been shown to dissuade individuals from criminal behavior (e.g., Sampson and Laub 1993). It follows that weak ties to the labor market, family, and civic institutions reduce the rewards from conventional activities, and in turn decrease the opportunity costs for crime. Thus, the contemporary system of punishment in the USA appears to stigmatize offenders upon release and long after their official punishment is meted out, cutting them off from participation in conventional society.

Sociological Research On The Consequences Of Punishment For Communities

Incarceration, particularly on a massive scale, can also have negative externalities for communities. When punishment is repeatedly and disproportionately applied to members of specific communities, it can alienate not only the individuals punished, but the entire community, who may begin to bear the burden of disproportionate punitive targeting. In the long run, such punitive trends may cause community members to view the legal system with a jaundiced eye, ultimately undermining the legitimacy of the system. This may occur in the absence of discrimination against community members; however, when there is evidence of discrimination, such as with racial profiling by police, the problem quickly escalates.

In his ethnography of youth culture in a predominantly African-American disadvantaged inner city, Anderson (1999) documents how perceptions of hostile and racist police practices, coupled with systematic barriers to employment and frequent contact with the law, drive community members to reject conformity with the law, and adopt a view of formal systems of sanctions as unfair and illegitimate. Consistent with the threshold view of the effects of stigma, norms of informally shaming offenders not only disappear, but are replaced by the “code of the street” – a set of norms that celebrates incarceration as a right-of-passage into manhood, and accepts interpersonal violence as a reasonable strategy for obtaining personal safety and social approval. This redefines formal punishment from a social cost within a community to a social reward, undermining deterrent effects. Because the legal system and police are often the principal contact disadvantaged residents have with conventional institutions, alienation from police may lead to distrust of other institutions.

In such disadvantaged neighborhoods, with a high prevalence of incarceration, low rates of conventional economic success, and meager community resources, young people will tend to underinvest in education and careers, which lowers the opportunity costs to crime. Facing grim economic prospects, they will tend to discount the future that, by all accounts, will be bleak (Anderson 1999). This discounting, which becomes part of the code of the street, induces an attitude of “live and die in the moment,” undermines delayed gratification and long-term planning, and blunts the deterrent effect of punishment.

High incarceration rates in specific communities result in large proportions of residents cycling in and out of prison, which may disrupt the local community (e.g., Clear 2007). On the one hand, removing an offender who has wreaked havoc on other residents, is isolated from others, and makes few contributions to the community may have a positive effect on the community as a whole. On the other hand, despite having committed a crime, local offenders may also have been fathers, neighbors, and friends, and thereby have been interwoven into the fabric of the local community. Their removal from the community through incarceration reduces social capital by eliminating the social ties they maintained within the community’s social network. The result is diminished exchange relationships, a loss of information potential, and weakened social norms. Ironically, this reduction in social capital may be associated with reductions in informal social control, such as collective efficacy, which in turn is associated with higher rates of crime and incarceration (e.g., Sampson et al. 1997). Such informal control includes interdependencies, trust, and mechanisms of control involving community reputations, all of which are destroyed by the constant uprooting of community members. Thus, a community can get caught up in a pernicious feedback loop in which incarceration undermines social control, which increases crime and incarceration, further undermining social controls. Furthermore, an influx of returning ex-prisoners into a disadvantaged community may disrupt local legal economies (shops and restaurants), reducing opportunity costs to crime, and may increase the community’s crime rate (e.g., Clear 2007). The devastating effects of mass incarceration at the community level undermine the salience of deterrence for all members, including those who would otherwise be at low risk of criminal behavior.

In sum, research on the social context of punishment and crime suggests a number of negative externalities of incarceration, particularly when carried out on a massive scale. Punitive policies in the USA may have helped deter crime, but have also produced a host of negative externalities – increasing stigmatization, hampering the reintegration of the offender, reducing the opportunity costs of crime, and undermining both social capital and informal social control of communities – all of which may have exacerbated the crime problem and reduced the efficiency of deterrence.

Conclusions And Directions For Future Research

Sociological theories of rational choice and deterrence have made strong contributions to our understanding of criminal behavior and punitive policies. Rooted in rational choice and utility maximization theories of individual behavior, aggregate studies of deterrence have been augmented by individual-level studies of decision making and cognition. In general, research suggests that deterrence has an important role in the causes of crime: based on a variety of research designs, the certainty of punishment appears to be negatively associated with crime. Research on the marginal deterrent effect of increasing the severity of punishment, including the death penalty, has been more equivocal, with effects typically modest in size or statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Increases in punishment rates, particularly mass incarceration, occur in a social context, which may lead to unanticipated consequences and negative externalities. Research in sociology and criminology suggests that a combination of mass incarceration with a failure to reintegrate offenders into the community has pronounced negative collateral consequences, including a reduction in the effectiveness of current deterrence policies. Large numbers of ex-prisoners have been stigmatized, blocked from succeeding in the labor market, prevented from civic participation, and generally isolated from conventional society, resulting in fewer opportunity costs for re-offending. The result is high rates of recidivism, and a constant cycling of predominantly disadvantaged African-American men in and out of the prison system. The removal of large numbers of men from disadvantaged communities may undermine the social organization, social capital, and informal control of those communities. Weakened community social controls combined with fewer opportunity costs for offending likely perpetuates the cycle of incarceration, stigmatization, and re-offending. As Braithwaite (1989) has argued, such a cycle will only lead to spiraling crime rates and diminished deterrent effects of stigmatized individuals; breaking the cycle requires reducing stigma, introducing community shaming, and increasing reintegration of the ex-offender into mainstream society.

Future research is needed to tease apart these countervailing processes of deterrence, stigmatization, and reintegration. Because each of these processes operates endogenously, research is needed that considers their joint nonlinear relationships. This is tricky because such processes will be fraught with feedback loops, as noted above, as well as cross-level effects: an individual decision to commit crime and risk incarceration changes the social context by providing criminal role models, reducing the certainty of arrest, and undermining social capital and informal control – all of which increases the likelihood of crime and incarceration. Research designs using experimental interventions, which provide instrumental variables for estimating treatment effects, may be useful here. Short of such costly designs, econometric methods of analyzing social interaction effects may help, although the identification problems are daunting. Another useful approach would be to estimate the models, and tease out the underidentified parameters using simulations based on game theory (see McCarthy 2002). Regardless of research design, we believe that the next generation of research on rational choice, deterrence, and crime must examine the dynamic interactions between criminal decision making and the broader social context within which decisions are embedded.

Bibliography:

- Anderson E (1999) Code of the street: decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. University of Chicago, Chicago

- Anwar S, Loughran TA (2011) Testing a Bayesian learning theory of deterrence among serious juvenile offenders. Criminology 49:667–698

- Apel R (2012) Sanctions, perceptions, and crime: implications for criminal deterrence. J Quant Crim 29(1):67–101

- Becker G (1968) Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Polit Econ 76:169–217

- Berk RA, Campbell A, Klap R, Western B (1992) The deterrent effect of arrest in incidents of domestic violence: a Bayesian analysis of four field experiments. Am Sociol Rev 57:698–708

- Braithwaite J (1989) Crime, shame and reintegration. Cambridge, New York

- Braithwaite J (1999) Restorative justice: assessing optimistic and pessimistic accounts. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 25. University of Chicago, Chicago, pp 1–12

- Bueno De Mesquita B, Cohen LE (1995) Self-interest, equity, and crime control: a game-theoretic analysis of criminal decision making. Criminology 33:483–518

- Clarke R, Cornish D (1985) Modeling offenders’ decisions: a framework for research and policy. Crim Justice 6:147–185

- Clear TR (2007) Imprisoning communities: how mass incarceration makes disadvantaged neighborhoods worse. Oxford University Press, New York

- Cook P (1980) Research in criminal deterrence: laying the groundwork for the second decade. In: Morris N, Tonry M (eds) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, vol 2. University of Chicago, Chicago, pp 211–268

- Durlauf SF, Nagin DS (2011) The deterrent effect of imprisonment. In: Cook PJ, Ludwig J, McCrary J (eds) Controlling crime: strategies and tradeoffs. University of Chicago, Chicago

- Durlauf SF, Fu C, Navarro S (2012) Capital punishment and deterrence: understanding disparate results. J Quant Criminol 21:1–19

- Goffman E (1963) Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

- Loughran TA, Paternoster R, Piquero AR, Pogarsky G (2011) On ambiguity in perceptions of risk: implications for criminal decision-making and deterrence. Criminology 49:1029–1061

- Manza J, Uggen C (2006) Locked out: felon disenfranchisement and American democracy. Oxford University Press, New York

- Matsueda RL, Kreager DA, Huizinga D (2006) Deterring delinquents: a rational choice model of theft and violence. Am Sociol Rev 71:95–122

- McCarthy B (2002) The new economics of sociological criminology. Annu Rev Soc 28:417–442

- Nagin DS (1998) Criminal deterrence research at the outset of the twenty-first century. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 23. University of Chicago, Chicago

- Pager D (2007) Marked: race, crime, and finding work in an era of mass incarceration. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Paternoster R (1987) The deterrence effect of the perceived certainty and severity of punishment: a review of the evidence and issues. Justice Q 4:173–217

- Piliavin I, Gartner R, Thornton C, Matsueda RL (1986) Crime, deterrence, and rational choice. Am Sociol Rev 51:101–119

- Rebellon C, Piquero NL, Tibbetts SG, Piquero AR (2010) Anticipated shame and criminal offending. J Crim Justice 38:988–997

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277:918–924

- Sherman LW, Berk RA (1984) The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. Am Sociol Rev 49:261–272

- Steinberg L (2009) Adolescent development and juvenile justice. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 5:459–485

- Wakefield S, Uggen C (2010) Incarceration and stratification. Annu Rev Soc 36:387–406

- Western B (2006) Punishment and inequality in America. Russell Sage, New York

- Williams KR, Hawkins R (1986) Perceptual research on general deterrence: a critical overview. Law Soc Rev 20:545–572

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.