This sample Restorative Justice and State Crime Research Paper is published for educational and informational purposes only. If you need help writing your assignment, please use our research paper writing service and buy a paper on any topic at affordable price. Also check our tips on how to write a research paper, see the lists of criminal justice research paper topics, and browse research paper examples.

Despite the continuing decline in the number of violent conflicts in recent years, the post-World War II period can be marked as one of the most violent periods in human history. The gross majority of the conflicts were intrastate conflicts involving flagrant and massive human rights violations. It is estimated that in the period 1945–1996 alone, 220 conflicts (not including international conflicts) resulted in 87 million deaths and many more millions of people stripped of their fundamental rights, property, and dignity (Balint 1996). In the final decades of the last century, various mechanisms for dealing with violent conflicts have come to light, in order to call the offenders to account and to provide compensation to the victims. The mechanisms that were put in place range from national and international tribunals or courts to nonjudicial forums like truth commissions. The emphasis on the development of more victim-oriented mechanisms is a logical continuation of the growing interest in the fate of victims in favor of the victors of conflicts. Some explain this profound shift as the progressive consolidation of the democratic model. At the same time, criminology and the understanding of crime have gone through the same paradigm shift – the social criminal as a survivor in poor communities has made room for the suffering victims.

The conflicts and crimes listed as prime examples of international crimes, that is, crimes incorporated in the Rome Statute of 1998 establishing the International Criminal Court, are as follows: (a) war crimes, (b) crimes against humanity, and (c) genocide. It should be noted that the large majority of these violent crimes are committed by states and their agents (e.g., police forces, army personnel, and intelligence services) and can therefore be considered state crimes (Rothe and Mullins 2010). However, the concept of state crimes is also wider, as it involves behavior that is not traditionally regarded as violent, such as instances of espionage or corruption.

This contribution largely equates state crimes with international crimes and leaves out the particular instances of treason, espionage, and corruption, which would merit a separate analysis. Its objectives are twofold: the first is to understand the recent developments that are gradually leading away from situations of impunity of international crimes toward situations of post-conflict justice into the face of a democratic transition; the second is to integrate the idea of restorative justice in the framework of post-conflict justice. The main argument is that the restorative justice theory, as an emerging discourse within the criminological sciences, may offer a promising approach toward the victims and perpetrators of mass violence. Moreover, it is suggested that it could contribute to broadening the object of criminology by shifting the attention from common crimes to political crimes and to deepening our theoretical understanding of the phenomenon of mass violence (Fig. 1).

The text takes the following structure. It first looks at the dominant approach to deal with international crimes, namely, retributive justice as evidenced through the criminal prosecutions of such crimes. It then shifts to a restorative justice approach and highlights its main features in the context of international crimes, by looking at truth commissions as the primary example of restorative justice. And, finally, it attempts to assess the relationship between these two very different models of justice in the case of violent conflicts and international crimes.

Retributive Justice Mechanisms And Their Shortcomings

The end of the twentieth century has witnessed the revival of international criminal justice in response to mass atrocities. The establishment of the International Criminal Court symbolizes this development. This first permanent international court will have the competency to judge individuals for having committed international crimes. It has been heralded by many as the start of a new era of justice. This era was already prepared by the establishment in 1993 and 1994 of two international ad hoc tribunals to deal with the gross human rights violations committed in the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and in Rwanda (ICTR). Furthermore, the world has witnessed the prosecution and conviction of four Rwandans in a Belgian court, charged with complicity in genocide in Rwanda. Perpetrators of international crimes can be prosecuted outside their home country, in a “third country,” on the basis of universal jurisdiction. It goes beyond the scope of this research paper to describe all the existing retributive justice mechanisms that are available to post-conflict states when dealing with gross human rights violations. Instead, it focuses on the basic features of criminal prosecutions at the national and the international level.

As argued elsewhere (Parmentier et al. 2008), the classical way to deal with international crimes has been to punish them and to use the criminal justice system for this purpose. This route fits into a retributive justice approach, according to which punishment is considered a justified response to crime because those who commit offenses deserve punishment. Much more than in the case of common crimes, criminal prosecutions for international crimes may take place at various levels, national and international. From the outset it should be clear that retribution is not the monopoly of criminal prosecutions, as also civil damages to victims, or the lustration of persons having worked for a former authoritarian regime, constitute illustrations of retribution. For the sake of the argument, however, the next paragraphs discuss retributive justice in terms of criminal law and criminal justice only.

Strengths And Weaknesses Of Criminal Prosecutions

Calls to bring the presumed offenders to a criminal court usually ring loud after a regime change has taken place, and the old authoritarian leaders have been replaced by a more or less democratic form of government. At that time, the political context tends to be more conducive to the necessary freedom of speech and of action. Moreover, the case of Pinochet has clearly illustrated that such calls for prosecution can be made long after the crimes have taken place. The former Chilean president and dictator was arrested in London in 1998 on charges of torturing political opponents during the early years of his dictatorship that ran between 1973 and 1990 but ultimately released by the British government on humanitarian grounds (old age and weak health).

The strong points of criminal prosecution for international crimes have been well documented. Huyse (1996) has listed two main arguments in these debates. The first is related to the reconstruction of the moral order, that is, the general idea that “justice be done” to satisfy the desire for justice of a society as a whole and of specific groups in particular. This moral argument is frequently coupled with a political one, in the sense that prosecution can also strengthen the fragile democracy, by confirming the principle of the “rule of law” and by thus providing the firm foundation on which to construct a human rights awareness and culture in the country. In such manner, criminal prosecutions serve the role of breaking through the thick walls of impunity and engage countries on the road to accountability. Closely linked to the reinforcement of the rule of law is the issue of deterrence, often voiced as a third argument. In this line of thought, to prosecute and punish perpetrators of international crimes will also serve to deter people from committing similar or other crimes in the future, both the perpetrator himself/ herself but also the population at large.

On top of these two arguments that primarily pertain to the issue of the desirability of criminal prosecution, there are also aspects of legality involved. Orentlicher (2007) has argued in strong terms that there exists “a duty to prosecute in international human rights law” for serious human rights violations, founding her arguments on the various human rights treaties that contain passages to this effect and on the ensuing case law. Nevertheless, she also accepts the distinction between the “global norm” (criminal prosecution for the most responsible perpetrators) and the “local agency” of enforcing and interpreting this norm (including non-prosecution for many low-level offenders). In general legal terms, criminal prosecutions and convictions have the advantage of establishing a “legal or judicial truth,” that is, an account of the acts and the facts that stands beyond doubt for the parties involved as well as for future generations. In the words of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, this truth is mostly “forensic” or “factual” (TRC Report 1998), and it is of course focused on individual perpetrators and victims.

In a large number of cases, the calls for criminal prosecution are voiced by the direct victims of the violations or crimes, those who directly suffered from arrests, torture, convictions, and other forms of repression. Also their relatives, and their surviving family members, who have witnessed the crimes and have felt their consequences from close by, tend to be staunch defenders of criminal prosecutions. They usually wish to know what has happened to their beloved ones and to see the offenders be called to account. The examples of the survivors of the Holocaust or the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo in Argentina (the so-called Crazy Mothers who for 30 years demanded clarifications from the successive governments for the disappearances of their relatives during the years of the military junta between 1976 and 1983) speak for themselves. In other cases, victims conduct their activities with the support of human rights groups and committees, local but also international, such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the Fe´de´ration Internationale des Droits de l’Homme.

It should be noted, however, that criminal prosecution is not without problems or even risks. Huyse (1996) has listed some of these risks. Contradictory as it may sound, criminal prosecutions of perpetrators may also undermine the “rule of law” of the new state. Some regimes may incur contradictions with the principle of nonretroactivity of criminal law, notably if they wish to prosecute crimes that were not prescribed or that were not punishable under the former regime. Another problem for the new state is to guarantee the independence and the impartiality of the criminal justice system. This is not always easy, because the criminal justice systems may still be populated by the same police offers and judges appointed by the former regime and still adhering to its values. The examples of Germany after World War II and South Africa after apartheid are telling in this respect. But also when the police officers and the judges are new to the system, problems may occur in that they may want to make a clear rupture with the past by adopting very repressive policies without due diligence for the rights of the accused. The reality of postwar repression in Western European countries has clearly illustrated the possible risks associated with such approach, which can lead to many controversies and tensions in the long run. And of course it is problematic to prosecute the offenders in the case of an amnesty rule that shields them off from further legal action, criminal and civil.

Another category of risks is less of a legal but more of a political nature. Many new democracies are fragile, as the old political and military elites can be resisting and actively opposing the transitional government. Prosecuting well-known offenders, or even the threat thereof, can provoke the old elites and even seduce them to seizing power again. The examples of Chile and Argentina are telling in demonstrating the power of the old elites and the caution with which the new government has proceeded. Another problem relates to the capacity of the system. In long-term autocratic regimes, only a small minority tends to possess the knowledge and the skills required to govern a country in political and economic terms. To call to account the members of this elite may lead to growing uncertainty about the future of the elites in general and may even push them to emigrate from the country, a scenario not unknown to countries from Central Europe in the early 1990s and to South Africa in the late 1990s.

Furthermore, there are problems with the logistics of criminal justice systems that are confronted with the legacy of mass violence. In some cases, the sheer numbers of offenders and potential suspects are so large that the system would become completely clogged if too many prosecutions were to take place. The example of Rwanda, where almost a decade after the genocide still over 100,000 persons were imprisoned, speaks for itself, and it has prompted the Rwandan government to look for new solutions and to revive the old conflict resolution model of Gacaca and to adjust it to dealing with the crimes of genocide (Penal Reform International 2002). Even in situations less extreme, it is unavoidable to be very selective and to only bring some perpetrators to the criminal court. Then a number of tough questions arise, namely, whether the prosecutorial agencies should aim at the heads and the planners of the crimes, who have ordered the crimes or were aware of them taking place, or whether they should target those who executed the orders and those who assisted them. And what about the so-called bystanders, who did not actively participate in committing the crimes but nevertheless witnessed them and in some cases may have benefited from the consequences?

Finally, criminal trials by their very nature are mostly focused on the offenders and on the rights of the accused and pay far less attention to the victims and to the harm inflicted upon them (Zehr 1990). This is the case with ordinary criminal trials, and it is by and large the same with international crimes and crimes of mass violence. This is not to say that victims are completely neglected but that their role in the criminal process is often reduced to that of witnesses or in other ways.

Given the many difficulties associated with criminal prosecution, many choices have to be made. Therefore, it does not come as a surprise that in practice criminal prosecution has often proved more the exception than the standard. Between the aspirations of criminal prosecutions and their realities, there exist many law and legal regulations, as well as several practical objections.

The Triptych Of Criminal Prosecutions

States are traditionally well equipped to conduct criminal prosecutions against suspects of regular crimes, through the various institutions of their criminal justice systems (notably the police, the Public Prosecutor’s Service, the trial courts, and the prison system or other measures for the execution of criminal sanctions). However, crimes of mass violence bring with them new challenges (Parmentier and Weitekamp 2007). One of the challenges lies in the political nature of the crimes, meaning that either the intent of the offenders or the object and context of their crimes relate to politics. Another distinctive criterion between common crimes and international crimes lies in the massive numbers of victims of the latter and sometimes in the large numbers of perpetrators as well. Therefore, criminal justice systems in many countries, particularly if poorly equipped, tend to be reluctant to engage in widespread prosecutions.

While in the past criminal prosecutions for international crimes were limited to the country where the crimes had been committed, the last two decades have witnessed two important shifts in this regard (Parmentier et al. 2008). The first shift relates to the development of so-called universal jurisdiction legislation in a number of countries. This allows third countries to prosecute and to try international crimes, without the existence of a link between the third country and the place where the crimes have been committed, the nationality of the offender, or the nationality of the victim. The main rationale lies in the fact that international crimes are considered so heinous that they not only affect the victims and the criminal justice system of the country where they took place but that they also affect humanity as such, for which reason also third countries put their criminal justice system at the disposal of the world community. Such cases of “pure” universal jurisdiction are in fact rare in today’s world, the actual Spanish legislation and the former Belgian legislation (until 2003) being among the exceptions. In fact, a number of countries – mostly European – have a limited form of universal jurisdiction and require at least one specific link with the crime in order to prosecute and try it. While welcomed by some as an ethical triumph for humanity, recent events in Western Europe suggest that the efforts to establish genuine systems of universal jurisdiction are often subject to the Realpolitik of international relations.

The second major shift to respond to mass atrocity lies in the establishment of criminal justice mechanisms at the international level. The forerunners of this tendency were the two ad hoc tribunals, for ex-Yugoslavia (ICTY) and for Rwanda (ICTR), set up by the Security Council of the United Nations in 1993 and 1994, respectively, for a limited period of time and with a limited territorial jurisdiction. They have been followed by the establishment of a permanent International Criminal Court, entering into operation in 2002 and dealing with three main categories of international crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. While the two ad hoc tribunals have a primary competence to deal with serious human rights violations, the ICC has a complementary task to prosecute and try international crimes when States Parties are “unwilling or unable” to do so, thus leaving the prime locus at the national level. It was followed by a number of mixed international-national tribunals, for Sierra Leone, East Timor, Kosovo, and Cambodia. The rapid development of international criminal justice mechanisms has been heralded by many as the final start of a new era of justice. Others, like Drumbl (2000), have argued that the practice of punishment by international tribunals is foremost an example of “legal mimicry,” whereby every new institution tries to build on the experience of the previous one, despite the many different crime situations they are facing and despite the often “confusing, disparate, inconsistent, and erratic” sanctions they have applied thus far. He raises very serious questions about the fact that international criminal justice has been strongly imbued with a western conception of justice, which is liberal and legalistic, and may not be the only model to deal with these “extraordinary” crimes that involve many victims, many perpetrators, and a large group of bystanders – and all of these within a political context. Moreover, some mechanisms run the risk to be driven by economic and political motives and lack the credibility to engage in the restoration of broken relationships in the society.

Restorative Justice Mechanisms And Their Promises

While the revival of the (international) criminal justice is often regarded as the starting point of a new era for justice in the case of mass violence, the preceding section exposed some of the major problems and shortcomings of the retributive approach to post-conflict justice. Moreover, retributive justice objectives will continue to represent only one side of the “coin of justice.” Given the many problems with prosecutions and retributive justice in general, recent years have arguably seen an increasing interest for other institutions and other models to deal with serious human rights violations and international crimes (Parmentier et al. 2008). The more than 40 truth commissions that have been established since the last quarter of the twentieth century are the best known examples of “second-best” solutions (Hayner 2011). Truth commissions have become strongly associated with restorative justice principles, and some like the South African one are among the few transitional justice mechanisms to be explicitly labeled as a restorative justice mechanism (Villa-Vicencio 2001). As a result there is increasing attention for the model of restorative justice and particularly for the applicability of restorative justice in situations of mass victimization and post-conflict justice (Weitekamp et al. 2006). Such approach requires “changing lenses,” as aptly put by Zehr (1990) in his seminal work on restorative justice for common crimes.

In this second part, it is argued that the road to post-conflict justice requires further steps that move beyond the limits of retributive justice. By prosecuting and punishing perpetrators of mass violence, many aspects of the phenomenon of mass victimization – such as its societal, victimological, and especially its criminological relevance – are overlooked. To reach some of the key goals of post-conflict justice, namely, to prevent the reoccurrence of the violent conflict and to repair the harm that was suffered during the conflict, it is crucial to consider a number of questions that are criminological par excellence: What are the causes of mass violence? What were the conditions that made this violent conflict happen? What are the sociological and psychological reasons that could explain people’s involvement in committing these atrocities? Here follows a short overview of how a restorative justice approach to post-conflict situations can offer a meaningful answer to these questions.

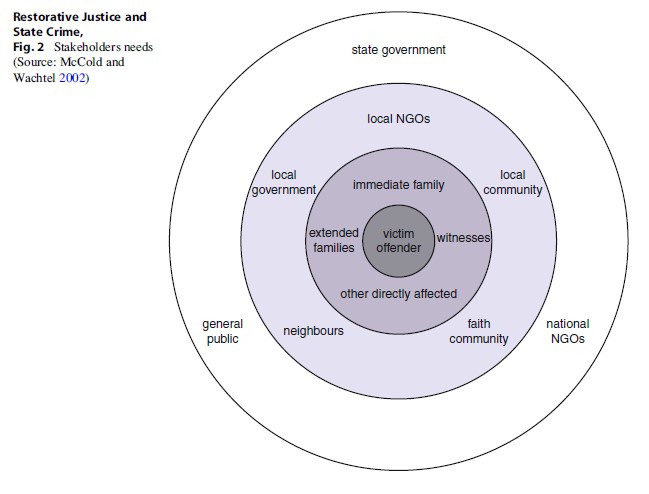

At this point, an important problem arises. Few concepts have been quoted more frequently in criminology during the last decade than the concept of restorative justice. At the same time, few concepts cover a more diversified meaning that this one, which is sometimes considered vague and fluid. The bottom line of restorative justice is to view crime as a violation of people and relations, thereby creating an obligation to make things right. This process should be facilitated by bringing victims and offenders together on a voluntary basis, such as in victimoffender mediation programs, and possibly also with the other stakeholders, for example, in restorative justice conferences. In these forums, room is made for dialogue and for creating an opportunity, with the help of a mediator, to restore the harm done and to reconcile the relation. For restorative justice scholars, crime is fundamentally a violation of people and interpersonal relationships, and restorative justice seeks to heal and put right the wrongs committed. In other words, restorative justice constitutes a different way of thinking about crime and our response to it. It focuses on the harm caused by crime and repairing the harm done to victims and reducing future harm by preventing crime. Therefore, need offenders assume responsibility for their actions and the harm they have caused? Restorative justice seeks redress for the victim, recompense by offenders, and reintegration of both within communities. This is achieved through cooperation by communities and the government. For Dignan and Marsh (2001), restorative justice has the following characteristics: the offenders’ personal accountability to those harmed by an offense, an inclusive decision-making process incorporating the key players, and the goal of putting right the harm caused by an offense. However, looking for a meaning that is widely accepted and that can serve as the starting base for our analysis is obviously no sinecure. At least four approaches can be identified to come to terms with restorative justice: (1) looking at definitions, (2) studying criteria, (3) identifying basic principles, and (4) developing models (Fig. 2).

It is striking that developments in restorative justice are almost exclusively focused on less serious property crimes and on juvenile crime, with a limited number of isolated examples of victim-offender programs for serious interpersonal crimes (e.g., Umbreit et al. 2003). But thus far very little attention has been paid to restorative justice for crimes of a political nature, sometimes reaching the level of mass violence and mass victimization (Christie 2001). However, viewing restorative justice in such a way that it may complement retributive mechanisms in dealing with mass violence allows for an extension of the concept of governance of international crimes. Before addressing the question if and how it can be used in the case of international crimes and state crimes, the meaning of restorative justice as developed in the area of criminology for common crimes has to be studied.

Definitions Of Restorative Justice

Although no commonly accepted definition seems to exist, the literature makes frequent reference to two types of definitions. Marshall defines restorative justice as “a process whereby parties with a stake in a specific offence resolve collectively how to deal with the aftermath of the offence and its implications for the future” (Marshall 1996, p. 37), whereas Bazemore and Walgrave are goal-oriented as they formulate restorative justice as “every action that is primarily oriented towards doing justice by repairing the harm that has been caused by the crime” (Bazemore and Walgrave 1999, p. 48). Additional definitions abound in the broad and rapidly growing field of restorative justice.

Criteria Of Restorative Justice

Definitions provided in the previous section remain somewhat general, and some would say quite vague. One way to make them more concrete is to enumerate specific criteria for restorative justice. The international community, personified by the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), has subscribed to the idea of restorative justice by adopting in 2002 a resolution encouraging countries to use Basic Principles on the Use of Restorative Justice Programmes in Criminal Matters to develop and implement restorative justice in their countries (www.restorativejustice.org).

The Basic Principles do not contain any formal definition of restorative justice, probably due to the fact that the text does not address the theory of restorative justice but is explicitly directed to particular programmatic expressions of restorative justice (Parmentier 2001). The text refers to “restorative justice programs,” meaning a program that uses restorative processes or aims to achieve restorative outcomes, two pillars that are clearly distinguished. “Restorative processes” imply those whereby all parties “affected by a crime actively participate together in the resolution of matters arising from the crime, often with the help of a fair and impartial third party,” as exemplified by mediation, conferencing, and sentencing circles. The second pillar, restorative outcomes, comprises agreements reached as the result thereof and explicitly includes restitution, community service, and other programs with an objective of reparation for victims and the community and reintegration of victims and offenders.

Rather than defining restorative justice, the Basic Principles enumerate various conditions under which restorative justice programs can and should actually work. These include, i.a., the availability of restorative justice programs at all stages of the criminal justice process, the voluntary character of restorative justice processes, the establishment of clear guidelines and standards governing the use of restorative justice programs, the importance of procedural safeguards in such processes, the issue of confidentiality, the importance of follow-up and implementation of agreements, the skills required for facilitators, and the importance of evaluation research. Through this focus on the working conditions of restorative justice programs, this text may be seen to mark the start of a more “conditional” approach to the problem of a common understanding of restorative justice.

Principles Of Restorative Justice

A third way to understand the meaning of restorative justice is to identify the key principles that are underlying. By way of example, Roche in his important book (2003) has identified four such principles: (1) personalism – crime is a violation of people and their relationships rather than a violation of (criminal) law; (2) reparation – the primary goal is to repair the harm of the victim rather than to punish the perpetrator; (3) reintegration – the aim is to finally reintegrate the perpetrator into society rather than to alienate and isolate him/her from society; and (4) participation – the objective is to encourage the involvement of all direct and possibly also indirect stakeholders to deal with the crime collectively. These principles allow for a close study of the restorative character of procedures and institutions.

Models Of Restorative Justice

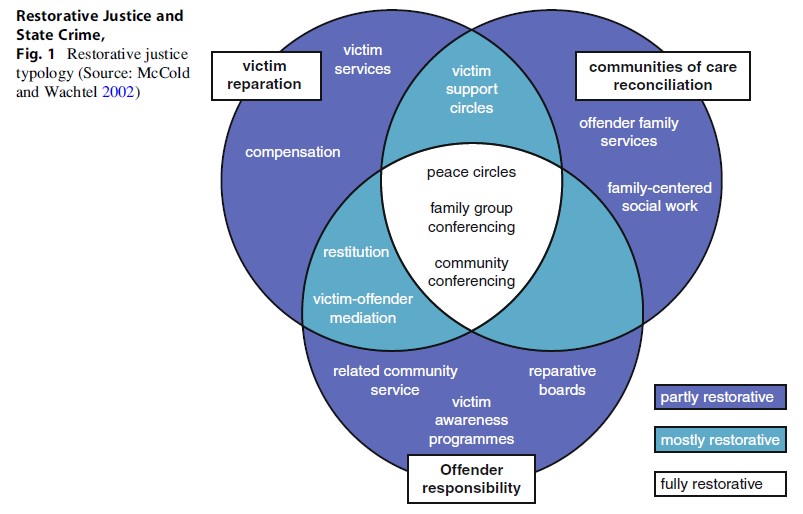

Finally, it can be argued that restorative justice can be conceptualized by developing various models. One very useful typology was developed by McCold and Wachtel (2002) who talk about three “degrees of restorativeness,” namely, “fully,” “mostly,” and “partly” restorative justice practices. These degrees depend on the degree of involvement of three actors, victims, perpetrators, and communities. As can be seen from the figure below, the authors consider family group conferences, peace circles, and community conferencing to be fully restorative while all other practices are only mostly or partly restorative.

The Relevance Of Restorative Justice For International Crimes: Looking Through The Lens Of Truth Commissions

Having sketched various approaches to restorative justice for so-called ordinary or common crimes, this contribution moves to indicating how restorative justice can be understood in the domain of international crimes, most of which are committed by states and their agencies. Rather than looking at all sorts of mechanisms that display some restorative features in dealing with international crimes, it is justified to focus on one specific mechanism, namely, truth commissions. In the following paragraphs, truth commissions will be looked upon, and it will be indicated how the principles and the models of restorative justice can be applied to them. At the same time, it should be noted that not all truth commissions share exactly the same features and therefore not all live up to the criteria of restorative justice (Villa-Vicencio 2001).

According to Hayner (2011), the following elements have to be present to speak of a truth commission: (1) it has to be set up with public (meaning state or government) support and cannot be the result of private initiatives only; (2) its objective is not to focus on individual cases but to sketch an overall pattern of human rights violations; (3) its major focus is on the victims who are provided ample opportunities to share their experiences of the crimes committed; (4) it finishes its work by a final report that is given publicity; and (5) the report contains recommendations about how to deal with the legacy of a dark past and how to avoid similar conflicts and crimes in the future. From the above it follows that a truth commission is quintessentially a nonjudicial body, set up for a limited duration, and without the intent to establish the guilt or innocence of individual persons but more to contribute to a form of conflict settlement between parties and at the level of society.

Such commissions of inquiry are increasingly considered as a valuable and a complementary practice to civil or criminal courts because of their strong emphasis on truth, reparation, and reconciliation (Christie 2001). The restorative dimension is particularly present at two levels: first, at the institutional level of the commission, as it provides a public forum for victims and offenders to voice and share their experiences, and secondly, at the interpersonal level where individual victims and offenders can meet during or after the process of the truth commission with a view to dialogue, personal healing, or restoration on the long term. Again, not all truth commissions adhere to the same operational rules, and there it is important to conduct specific case studies to reveal in which way and to which degree truth commissions fulfill their promise of providing restorative justice (Parmentier 2001). The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) provides an interesting example of how such commissions may contribute to restorative justice, in this case through the work of its three separate committees (TRC 1998): first, by providing a forum to victims during the public hearings organized throughout the country as part of the Human Rights Violations Committee, which in limited cases have led to an encounter between victims and suspects or representatives of the apartheid regime; second, through actual encounters between offenders applying for amnesty to the Amnesty Committee and therefore being obliged to disclose all relevant facts, which in some instances led to a dialogue with the victims or survivors; and third, through the recommendations of the Reparation and Rehabilitation Committee that issued recommendations to the government on matters of reparation and rehabilitation.

Other examples of mechanisms with restorative justice aspects include customary mechanisms, also called community-based mechanisms, such as the Gacaca tribunals in Rwanda, set up to process the high numbers of alleged perpetrators of genocide in detention and with the objective to strike a balance between justice and reconciliation (Penal Reform International 2002).

Principles Of Restorative Justice And Truth Commissions

Roche’s four principles of restorative justice can easily be applied to truth commissions and particularly to the one in South Africa (Parmentier et al. 2008).

First of all, the principle of personalism, meaning that crime is a violation of people and their relationships rather than a violation of (criminal) law, finds application. This principle refers to the social dimension of “emotional involvement” that enables the conflicting parties to restore the broken relationships. Crimes of mass violence are first of all violations of people rather than violations of law. Truth commissions do bear the promise of being a “fully restorative justice process” if they stress the importance of encounters between victims and offenders and are also able to live up to these expectations (Weitekamp et al. 2006). One of the implications of such encounter is to organize victim-offender dialogues, either as part of the truth commission process or outside of its direct ambit. In that case, the key issue of “encounter” should be included as a new element in future truth commissions. To date no single truth commission has gone as far as bringing perpetrators and victims together to deal collectively with the aftermath of the violent conflict, with the possible exception of some amnesty hearings in the South African TRC. In the South African case, and presumably in other post-conflict nations as well, there is quite a lack of information on how and, more importantly, to what extent victims’ expectations were effectively met through the TRC process, and very little is known about their backgrounds, expectations, and motivations. As to the offenders, it is already shown that if they are brought around the table, it might help to reverse the process of dehumanization of the perpetrator (Drakulic 2004). On a more general level, van der Merwe has illustrated how the national plan for reconciliation in post-apartheid South Africa has led to efforts to obstruct and to hamper the individual process of reconciliation for many victims (van der Merwe 2001). Finally, it should be noted that there exist many more legitimate responses to mass victimization after violent state conflict that are culturally and socially appropriate responses attempting to bring people together in some way. One of the examples could be the Gacaca tribunals in Rwanda (Penal Reform International 2002). Responses could also include a blend of mechanisms that form an integrated response to deal with the past.

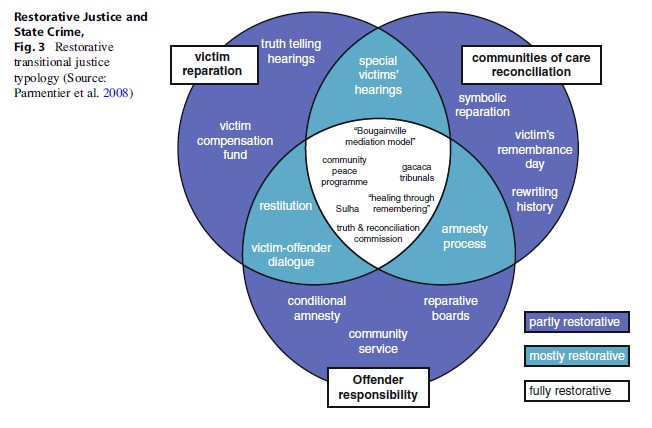

The second principle of reparation, the primary goal of which is to repair the harm of the victim rather than to punish the perpetrator, is more difficult to apply straightforwardly. Reparation is becoming increasingly important to address, and even undo, the injustices of the past, and the last decade has witnessed an enormous increase of the awareness in this regard. According to the UN resolution of 2005 holding the Basic Principles and Guidelines on Reparation, reparation is to be understood as a very wide concept, including restitution of goods, financial compensation, rehabilitation through social and medical measures, symbolic measures, and guarantees of non-repetition of the alleged acts. All of these measures can be individual or collective. While the principle is now firmly established in international law (Sarkin 2004), many questions do remain (Du Plessis and Pete´ 2007). Although it is generally accepted that the beneficiaries of reparation are the victims, it is less clear how far to stretch this category and whether also indirect victims or society as a whole can be included. Another issue is how to enforce the right to reparation, through a general government policy or through individual administrative or judicial action? Apart from preventing conflicts to reoccur the restorative justice principle of reparation is a primary goal of transitional justice. For a long time in the debates on transitional justice, reparation was promulgated as a necessary mechanism, but only a few examples have shown a successful outcome. In the years to come, reparation is expected to rise high on the transitional justice agenda. In the context of the South African TRC, reparations were present at various levels (TRC Report 1998): the Reparation and Rehabilitation Committee awarded urgent and interim reparations to those victims who had provided written or oral testimony to the TRC and were in need of medical, psychological, or material help; it also recommended to the government to take measures of various nature, including individual reparations, symbolic reparations, and legal and administrative matters, community rehabilitation programs, and institutional reforms. It has to be said that the recommendations have not led to the expected results on the part of the government, and many victims have tried to force the government to implement these recommendations by bringing their claims to the collective level of victim support groups, direct lobbying, and even court cases. It remains to be seen what the concrete outcomes of such actions have been (Fig. 3).

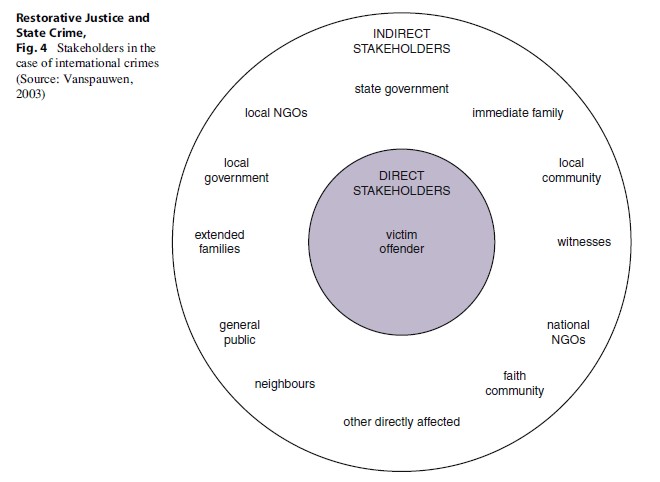

The principle of reintegration, meaning that the aim is to finally reintegrate the perpetrator into society rather than to alienate and isolate him/ her from society, poses another set of difficult problems. In retributive justice the focus is on the accountability of offenders, namely, calling to account those who have committed gross violations of human rights that sometimes amount to international crimes. In contrast to common understanding, accountability is far from a straightforward reality. One of the main problems relates to the type of offenders to be called to account, the heads and the planners of the violations or those who executed the orders and those who assisted them, and what to do with the “bystanders” who did not actively participate in committing the crimes but may have benefited from the consequences? On top of that, it should be clear that international crimes only constitute the symptoms of a violent conflict. Dealing with the most serious crimes without dealing with the underlying conflict itself is merely touching the tip of the iceberg. A restorative justice approach to accountability is necessarily different, particularly when coupled with the key principle of reintegration. This principle demands from a society that it aims to hold perpetrators accountable for their wrongdoings in a supportive way, taking into account all the needed measures to work toward their reintegration into the same society. The merely punitive approach of trials leaves little room for future reintegration, and this same argument applies to states that choose not to face their violent past and decide to live in a permanent state of denial (Cohen 2001) or amnesia. A restorative justice approach to the issue of accountability is geared toward cooperation with the perpetrator, to resolve problems and to reintegrate rather than to alienate or isolate the perpetrator from his/her society. Providing a high level of support to perpetrators while not minimizing the control over the accountability process could arguably provide the most sustainable and durable response to dealing with perpetrators of serious human rights violations. Another aspect going to the heart of reintegration relates to the beneficiaries of international crimes and serious human rights violations. There is a great deal of controversy around the issue of involving the benefiting parties in the process of accountability and reparation. The experiences of the South African TRC on the (lack of) involvement of beneficiaries show the sensitive character of this matter. The amnesty hearings of the TRC focused only on individual perpetrators, and the institutional hearings with large sectors of society (e.g., business, media, and medical and legal profession) were purely voluntary. In this way, the structural evil of apartheid as a system was largely downplayed in favor of the misdeeds committed by some individuals. According to some, the beneficiaries of apartheid were let off the hook without being obliged to confront their past in a direct way (Mamdani 2000) (Fig. 4).

And fourthly, the principle of participation, whereby the objective is to encourage the involvement of all direct and possibly also indirect stakeholders to deal with the crime collectively, is applied. This principle refers to the dimension of empowerment and stresses that those affected by the crime need to regain their sense of autonomy. This can only be achieved when the stakeholders are actively involved in the process, and we distinguish two categories of stakeholders: those directly affected by the crime and those indirectly involved but not emotionally affected. In post-conflict situations, it is an enormous task to clarify the different roles and stakeholders that were affected either directly or indirectly and either personally or structurally by a violent past whereby gross violations of human rights were committed by the state on the one hand and by groups of the society (e.g., liberation movements, activists, minorities) on the other hand. Very few people will appear to be not affected at all, so that dealing with mass victimization in post-conflict situations will seem to be an insurmountable task to fulfill. Overall, restorative justice pays a lot of attention to victims and their needs, but a problem may arise when the group of victims is systematically narrowed. In the process of the South African TRC, for example, many victims could not be taken into account because they were not “victimized enough” according to the mandate. Only victims of gross human rights violations were defined as victims in the TRC Act. For a huge number of victims, there seems not to have been a feeling of justice at all, notably the victims of structural apartheid and the victims who suffered from the everyday apartheid policy. A lot of victims were disappointed and embittered after the proceedings of the TRC and felt that their rights and feelings had been neglected and justice was not gained. In this respect, it is also important to consider the distinction between individual and collective victims, direct and indirect victims, and see to what extent we can broaden up the definition of what victims are so that they can all have their place they deserve in the process of transition. In other words, while the process of truth seeking in the TRC has gone far beyond forensic forms of truth in individual cases and has involved narrative and social truth in a collective framework, it has still fallen short of allowing the participation of a wide range of victims of apartheid. Not all stakeholders were present in all parts of the procedures. They were mostly present in the hearings of the amnesty committee (AC), which always involved the amnesty applicants and the public and sometimes also the victims or their relatives. In the Human Rights Violations Committee hearing, the same three parties were sometimes present but sometimes not (only victims and the public). The picture is therefore mixed, moreover so because at the end of the day, only 22,000 victims in one way or another participated in the TRC’s work, which in light of the many millions only constitutes a tiny fraction.

Models Of Restorative Justice And Truth Commissions

Another way to assess the restorative justice aspects of truth commissions is to apply the model of restorativeness as developed by McCold and Wachtel. Using the three basic actors, perpetrators, victims, and communities, it is possible to reinvent their model into a “restorative transitional typology” to fit the purposes of international crimes and post-conflict justice (Parmentier et al. 2008). As a result, six practices could be considered as fully restorative, including truth commissions (under the condition they allow encounters between offenders and victims), community peace programs (if they allow sufficient space for victims and offenders), Gacaca tribunals (provided they reserve a proper place to the community), the mediation model applied in Bougainville (Braithwaite 2002; see infra), the practice of Sulha (the middle eastern model of doing justice), and healing through remembering programs in various parts of the world. It goes without saying that much more research is needed, particularly in the countries concerned, to find out all the details of these practices.

Toward An Integrated Approach Of Retributive And Restorative Justice In Post-Conflict Situations

Having sketched the strengths and weaknesses of retributive justice models in relation to international and state crimes, and having indicated the features of restorative justice and its potential to be applied for such crimes, one crucial question comes up consistently: how to understand the relationship between both models of justice in the case of international crimes and in the context of post-conflict justice?

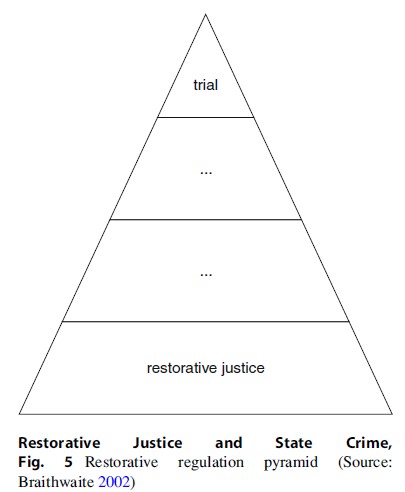

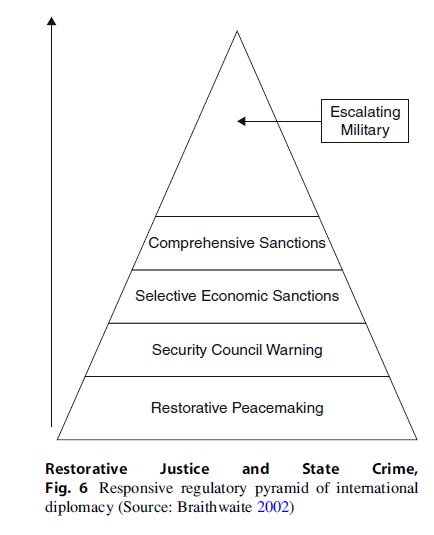

Much has been written about this one-million-euro question, and it would go far beyond the limits of this research paper to deal with all possible answers in the literature. Instead, it is focused on the theoretical work of the very influential work of Australian criminologist John Braithwaite (2002). He has consistently argued that it is always feasible (and preferable) to adopt a restorative justice approach at the start and try to uphold it as long as possible. At the same time, the level of pressure and coercion can be gradually increased, and if nothing convinces the stakeholders to enter into a restorative practice, it is possible to go back to the retributive approach. In other words, while restorative justice is the preferred model to deal with conflicts and crimes, a certain degree of coercion may be unavoidable. For Braithwaite, this theory works both in the case of common crimes (the “restorative regulation pyramid” below) as in the case of violent conflicts involving international and state crimes (the “responsive regulatory pyramid of international diplomacy” below) (Figs. 5 and 6).

The theory provides a very useful and promising framework to conceptualize the relationships between retributive justice and restorative justice. In the context of international crimes and post-conflict justice, it provides a better understanding of how both models of justice could work together and even complement one another. But of course, much more research is needed, both of a theoretical and an empirical nature, to grasp the full details of such complex relationship.

Others have tried to gain further insight into this matter by developing two models of post-conflict justice. The first analyzes the building blocks of post-conflict justice and identifies seven key issues for any government to deal with in the aftermath of violent conflicts: truth, accountability, reparation, reconciliation, trauma, trust, and dialogue (Parmentier and Weitekamp 2007; Weitekamp and Parmentier 2012). The second model relates to the interplay between retributive and restorative justice instruments that can be used in national and international interventions after violent conflicts have come to an end (Weitekamp et al. 2006). The interested reader is referred to the literature contained therein.

Conclusion

In the aftermath of violent conflicts and the commission of international crimes, often by state agencies, the dominant approach is to start criminal prosecutions against the alleged perpetrators. While prosecutions take place at the national and the international level, many problems continue to abound in terms of capacity, impartiality, and the like. Moreover, little if any attention is paid to a restorative justice approach in dealing with international and state crimes. One of the reasons is the multiple understanding of what restorative justice really means and implies.

This contribution has highlighted various ways of viewing restorative justice and has applied some of these to the field of international crimes, by looking through the lens of truth commissions that have emerged in international relations over the last 30 years. It can be argued that restorative justice is a useful approach to consider in cases of international crimes. At the same time, the relationship between retributive and restorative justice is far from clear and in fact very complex. More research is needed, theoretical and empirical, to develop sound models for understanding and for intervening during and after violent conflicts.

Bibliography:

- Balint J (1996) Conflict, conflict victimization, and legal redress: 1945–1996. Law Contemp Probl 59:231–247

- Bassiouni MC (ed) (2002) Post-conflict justice. Transnational Publishers, Ardsley

- Bazemore G, Walgrave L (1999) Restorative juvenile justice: in search of fundamentals and an outline for systemic reform. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey

- Braithwaite J (2002) Restorative justice and responsive regulation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Christie N (2001) Answers to atrocities. Restorative justice in extreme situations. In: Fattah E, Parmentier S (eds) Victim policies and criminal justice on the road to restorative justice. Essays in honour of Tony Peters. Leuven University Press, Leuven

- Cohen S (2001) States of denial. Knowing about atrocities and suffering. Polity Press, Cambridge

- Dignan J, Marsh P (2001) Restorative justice and family group conferences in England: current state and future prospects. In: Maxwell G, Morris A (eds) Restoring justice for juveniles: conferences, mediation and circles. Hart Publications, Oxford

- Drakulic S (2004) They would never hurt a fly. Abacus, London

- Drumbl MA (2000) Punishment, post genocide, from guilt to shame to civis in Rwanda. New York U Law Rev 75:1221–1326

- Du Plessis M, Pete´ S (eds) (2007) Repairing the past? International perspectives on reparations for gross human rights abuses, vol 1, Series on transitional justice. Intersentia Publishers, Antwerp/Oxford

- Hayner PB (2011) Unspeakable truths. Confronting state terror and atrocity. Routledge, New York

- Huyse L (1998) Justice after transition: on the choices successor elites, make in dealing with the past. In: Jongman A (ed) Contemporary genocides. PIOOM, Leiden

- Mamdani M (2000) A diminished truth. In: James W, van de Vijver L (eds) After the TRC. Reflections on truth and reconciliation in South Africa. David Philip Publishers, Claremont

- Marshall TF (1996) Restorative justice. An overview. Home Office: Research Development and Statistics Directorate, London

- McCold P, Wachtel T (2002) Restorative justice theory validation. In: Weitekamp E, Kerner H-J (eds) Restorative justice: theoretical foundations. Willan Publishing, Devon, pp 110–142

- Orentlicher D (2007) Settling Accounts’ revisited: reconciling global norms with local agency. Int J Transit Justice 1:10–22

- Parmentier S (2001) The South African truth and reconciliation commission. Towards restorative justice in the field of human rights. In: Fattah E, Parmentier S (eds) Victim policies and criminal justice on the road to restorative justice. Essays in honour of Tony Peters. Leuven University Press, Leuven

- Parmentier S, Weitekamp EGM (2007) Political crimes and serious violations of human rights: towards a criminology of international crimes. In: Parmentier S, Weitekamp EGM (eds) Crime and human rights, Series on sociology of crime, law and deviance. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 109–144

- Parmentier S, Vanspauwen K, Weitekamp EGM (2008) Dealing with the legacy of mass violence: changing lenses to restorative justice. In: Smeulers A, Havemann R (eds) Supranational criminology: towards a criminology of international crimes. Intersentia, Antwerp/Oxford, pp 335–356

- Penal Reform International (2002) Interim report on research on Gacaca jurisdictions and its preparations (July–December 2001). Penal Reform International, London

- Roche D (2003) Accountability in restorative justice. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Rothe D, Mullins C (eds) (2010) State crime: current perspectives. Rutgers University Press, Piscataway

- Sarkin J (2004) Pursuing private actors for reparations for human rights abuses committed in Africa in the courts of the United States of America. In: Doxtader E, VillaVicencio C (eds) Repairing the irreparable. Dealing with the double-binds of making reparations for crimes in the past. David Philip, Claremont

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (1998) Truth and reconciliation commission of South Africa report. Juta Publishers, Cape Town, 5 volumes

- Umbreit MS, Bradshaw W, Coates RB (2003) Victims of severe violence in dialogue with the offender. Key principles, practices, outcomes and implications. In: Weitekamp EGM, Kerner HJ (eds) Restorative justice in context. International practice and directions. Willan Publishing, Cullompton

- van der Merwe H (2001) National and community reconciliation: competing agendas in South African truth and reconciliation commission. In: Biggar N (ed) Burying the past: making peace and doing justice after civil conflict. Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC

- Villa-Vicencio C (2001) Restorative justice in social context: the South African truth and reconciliation commission. In: Biggar N (ed) Burying the past: making peace and doing justice after civil conflict. Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC

- Weitekamp EGM, Parmentier S (2012) On the road to reconciliation; the attempt to develop a theoretical model which applies restorative justice mechanisms in post-conflict societies. In: Plywaczewski E (ed) Current problems of the penal law and criminology. Wolters Kluwer Polska, Warszawa, pp 795–804

- Weitekamp EGM, Parmentier S, Vanspauwen K, Parmentier S, Vanspauwen K, Valinas M, Gerits R (2006) How to deal with mass victimization and gross human rights violations. A restorative justice approach. In: Ewald U, Turkovic K (eds) Largescale victimization as a potential source of terrorist activities. Importance of regaining security in postconflict societies. Ios Press, Amsterdam, pp 217–241

- Zehr H (1990) Changing lenses. A new focus for crime and justice. Herald Press, Scottdale

See also:

Free research papers are not written to satisfy your specific instructions. You can use our professional writing services to buy a custom research paper on any topic and get your high quality paper at affordable price.